Abstract

The effects of religiosity on well-being appear to depend on religious orientation, with intrinsic orientation being related to positive outcomes and extrinsic orientation being related to neutral or negative outcomes. It is not clear, however, why intrinsic and extrinsic religiosity has the relationships they do. Self-determination theory may provide a useful framework of intrinsic and extrinsic aspirations that may help to answer this question. The purpose of the present study was to examine whether intrinsic and extrinsic religiosity would be related to intrinsic and extrinsic life aspirations. We hypothesized that intrinsic religiosity would be positively related to intrinsic life aspirations and negatively related with extrinsic life aspirations, and that extrinsic religiosity would be positively related to extrinsic life aspirations and negatively related to intrinsic aspirations, and that life aspirations would partially mediate the relationships between religious orientation and outcome. To study these hypotheses, a random national sample (total number of 425, average age of 52, 59 % female) completed the measures of religious orientation, life aspirations, affect, and life satisfaction. It was found that intrinsic religiosity was positively related to positive affect, life satisfaction, and intrinsic life aspirations and was negatively related to negative affect and extrinsic life aspirations. Extrinsic religiosity was positively related to extrinsic life aspirations and was not related to the intrinsic life aspirations. When both religious orientation and life aspiration variables were included together in the model predicting outcome, both remained significant indicating that religious orientation and life aspirations are independent predictors of outcome. In conclusion, although religious orientation and life aspirations are significantly related to each other and to outcome, life aspirations did not mediate the effects of religious orientation. Therefore, self-determination theory does not appear to completely account for the effects of religious orientation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In general, religiosity is related to positive health outcomes (Chida et al. 2009; McCullough et al. 2000; Koenig and Vaillant 2009; Smith et al. 2003; Steffen 2012). Some studies, however, that have found that religiosity can have a negative effect on health (e.g., Pargament et al. 2003; Smith et al. 2003). For example, individuals with a primarily extrinsic religious orientation, where religion is used in a self-serving way to obtain rewards or acceptance, tend to have worse health than individuals with a primarily intrinsic religious orientation, where religion is a framework for understanding life and is an end in and of itself (Smith et al. 2003). It is not clear, however, why intrinsic and extrinsic religiosity differs in their relationships with outcomes. Self-determination theory provides a framework for understanding the relationships between intrinsic and extrinsic religiosity and well-being Neyrinck et al. 2005, 2010). Specifically, intrinsic religiosity may contribute to positive well-being because it leads people to pursue intrinsically focused goals, whereas extrinsic religiosity leads to neutral or negative well-being because it leads people to pursue extrinsically focused goals (Kasser and Ryan 1993, 1996; Ryan et al. 1993). The purpose of the current study is to examine these possibilities.

Self-determination Theory and Life Aspirations

Self-determination theory focuses on motivation (Deci and Ryan 1985; Ryan and Deci 2000). People can be motivated by both intrinsic and extrinsic factors. People can be intrinsically motivated to action by personal interests, curiosity, or life values. People can also be extrinsically motivated to action by external reward systems, evaluations, and the opinions of others. A large body of research has shown that optimal health is achieved when people act from an intrinsic orientation (Ryan and Deci 2000). People who are primarily intrinsically oriented are more satisfied with life, more creative, and having higher self-esteem. People who are intrinsically oriented or “self-determined” engage in life in a way that is interesting, personally important, and vitalizing. Self-determination can be thought of as a continuum ranging from a motivation (nonself-determined) to extrinsic motivation to intrinsic motivation (self-determined). As people move toward intrinsic motivation and self-determination, their enjoyment and life satisfaction increases.

Kasser and Ryan (1993, 1996) developed a life aspirations approach to specifically study the impact of certain life goals from a self-determination theory perspective. The three main intrinsic aspirations are self-acceptance, affiliation, and community feeling. Intrinsic goals are primarily satisfying in and off themselves because they satisfy inherent psychological needs such as relatedness, autonomy, and personal growth (Deci and Ryan 1985; Ryan and Deci 2000). Scoring higher on intrinsic aspirations has been related to better health and well-being (Kasser and Ryan 1993, 1996). The three main extrinsic aspirations are financial success, social recognition, and appearance (Kasser and Ryan 1996). Extrinsic goals are not primarily satisfying in and of themselves but are engaged in for public admiration because they make one look good. The pursuit of extrinsic rewards is not necessarily either positive or negative. However, achieving extrinsic goals can have negative consequences for two reasons: first, they do not meet basic needs of the individual; second, they take time and energy away from pursing intrinsic goals that do meet needs. Excessive focus on extrinsic aspirations has been related to worse mood, less self-actualization, more concern with what others think, and less emotion-behavior congruence (Kasser and Ryan 1993, 1996).

Religious Orientation and Life Aspirations

Conceptually, intrinsic religiosity and intrinsic life aspirations have significant overlap. Intrinsic religiosity involves a genuine heartfelt faith that provides a meaning framework in which all of life is understood (Allport and Ross 1967). Intrinsic religiosity can serve an integrative function and give meaning in a person’s life, especially during difficult times. A number of studies have shown a relationship between intrinsic religiosity and positive health outcomes (Smith et al. 2003; Donahue 1985).

As with intrinsic religiosity and life aspirations, extrinsic religiosity and extrinsic life aspirations are conceptually related. Extrinsic religiosity is a utilitarian and self-serving use of religion as a means to an end, but not an end in itself (Smith et al. 2003; Donahue 1985). As such, extrinsic religiosity can be viewed as an instrumental approach to religion shaped to suit oneself. For example, a key purpose in church attendance for those high on extrinsic religiosity is to gain social status. Extrinsic religiosity is usually related to neutral or negative health outcomes (see Smith et al. 2003). Similarly, extrinsic life aspirations are related to neutral or negative outcomes (Kasser and Ryan 1993, 1996).

Ryan et al. (1993) examined the relationships between religious orientation and outcomes from a self-determination theory perspective. Specifically, they studied religious internalization, comparing a new measure of religious introjection and identification to established measures of religiosity including the Allport and Ross’s (1967) Religious Orientation Index. Identification correlated highly with intrinsic religiosity and introjection correlated with extrinsic religiosity, indicating that intrinsic religiosity was related to more intrinsic motivation (and better outcomes) and extrinsic religiosity was related to more extrinsic motivation (and worse outcomes). Steffen (2013), in a study of highly religious individuals, found that religious orientation and life aspirations were significantly related but that life aspirations did not mediate the relationships between religious orientation and affect and life satisfaction. Given the findings of Ryan et al. (1993), however, it is possible that life aspirations may partially mediate religious orientation and outcome in a general population sample that includes a wider degree of religiousness.

The Present Study

The purpose of the present study was to examine whether intrinsic and extrinsic religious orientations would predict intrinsic and extrinsic life aspirations. Three sets of hypotheses were examined. First, it was hypothesized that that intrinsic religiosity and intrinsic life aspirations would predict decreased negative affect, increased positive affect and satisfaction with religious/spiritual life, and social life; and that extrinsic religiosity and extrinsic life aspirations would predict increased negative affect, and decreased positive affect, satisfaction with religious/spiritual life, social life, and materialistic well-being. Second, it was hypothesized that intrinsic religiosity would predict increased intrinsic life aspirations and decreased extrinsic life aspirations, whereas the opposite would be true for extrinsic religiosity. And third, it was hypothesized that life aspirations would partially mediate the relationships between religious orientation and outcome.

Methods

Participants

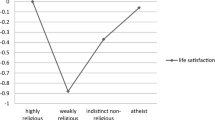

Potential participants were selected via random probability sampling of 2,000 US adults across the country. Of the initial mail out of 2,000 questionnaire packets with cover letters explaining the study and return stamped envelopes, 425 usable questionnaires were returned for a response rate of 21.3 %. Given the sensitive nature of the questionnaires, confidentiality and anonymity were emphasized. The sample collected had an average age of 52 (SD 16), was 59 % female, with 71 % having some college education, 41 % reporting having an income over $40,000, 89 % were white, and 64 % were married (see Table 1).

Measures

Religious Orientation

Religious orientation was measured using Allport and Ross’s (1967) Religious Orientation Index. Intrinsic religiosity was measured using questions such as “I try hard to carry my religion over into all my dealings in life” and “My religious beliefs lie behind my whole approach to life.” Extrinsic religiosity was measured using questions such as “church is important as a place to make good social relationships” and “The main purpose of prayer is to gain relief and protection.” Because previous research has shown differential findings between socially oriented extrinsic religiosity and personally oriented extrinsic religiosity, those two subscales were used in this study. These questions were asked on a five-point Likert scale with one indicating “strongly disagree” and five indicating “strongly agree.” The Cronbach’s alpha for the intrinsic scale was .87 and .61 for the extrinsic scale.

Affective Well-being and Satisfaction

To assess affective well-being, participants were asked questions about their current feelings (Andrews and Robison 1991). Negative affect was measured asking questions about how anxious, depressed, displeased, and unhappy they felt. Positive affect was measured asking how enthusiastic, pleased, contented, and happy they felt. These questions were administered via a six-point Likert scale with one indicating “Never” and six indicating “all the time.” The Cronbach’s alpha for negative affect was .75 and for positive affect was .83.

To assess satisfaction with life, participants were asked questions about their satisfaction with their religious and spiritual lives, their social lives (friends, family, etc.), and their material well-being (job, finances, standard of living, etc.) (Andrews and Robison 1991). Questions were rated on a five-point scale with one indicating “strongly disagree” and five indicating “strongly agree.” The Cronbach’s alphas were .80 for religious satisfaction, .76 for social satisfaction, and .78 for material satisfaction.

Extrinsic Life Aspirations

Extrinsic life aspirations were measured using Richins and Dawson (1992) materialism scale. The materialism scale defines materialism as being comprised of values central to one’s life, with concern over having material possessions and the hope that they will be admired because of their material possessions. Typical questions include “Some of the most important achievements in life include acquiring material possessions,” “I like to own things to impress people,” and “I admire people who own expensive homes, cars, and clothes.” The materialism scale is measured on a five-point scale from “not at all descriptive” (one) to “extremely descriptive” (five). A factor analysis of the scale revealed that six items did not load as expected. Therefore, 12 of the original 18 items were included that loaded according to Richins and Dawson’s theory. The overall scale had a Cronbach’s alpha of .81.

Intrinsic Life Aspirations

Intrinsic life aspirations were adapted from the list of values (Kahle 1983, 1996; Rokeach 1973). Participants were asked to rate how important or unimportant the following characteristics were in their lives: warm relationships with others, sense of belonging, self-fulfillment, self-respect, and sense of accomplishment. Questions were asked on a five-point Likert scale with one indicating “not at all” and five indicating “extremely.” These items have been related to overall well-being in previous studies (Kahle 1996). The Cronbach’s alpha for the intrinsic life aspiration variable was .77.

Analytic Strategy

The purpose of this study was to examine the relative relationships among intrinsic religiosity, extrinsic religiosity, intrinsic life aspirations (self-respect, importance of relationships), and extrinsic life aspirations (respect from others, materialism), as well as their relationships with affective well-being outcomes variables (feeling happy, pleased, anxious, or depressed) and satisfaction outcome variables (overall satisfaction with life, satisfaction with work, satisfaction with their spirituality, and satisfaction with church or religion). Demographic variables were analyzed descriptively with the results presented in Table 1. Hierarchical regression analyses controlling for age and gender were used to examine the hypotheses with the standardized beta weights presented in the tables. Regression was also used to examine the mediational hypotheses.

Results

Religious Orientation and Well-being

The first set of hypotheses stated that intrinsic religiosity and intrinsic life aspirations would predict increased positive outcomes and decreased negative outcomes with the opposite being true for extrinsic religiosity and extrinsic life aspirations. For all the hypotheses examined, hierarchical regression analyses were used entering in gender and age as control variables first before entering the variable of interest in all models. Scoring higher on intrinsic religiosity predicted decreased negative affect (β = −.18, p < .001), increased positive affect (β = .14, p = .005), increased satisfaction with their religious/spiritual lives (β = .64, p < .001), and increased satisfaction with their social lives (β = .11, p = .03) (see Table 2). Intrinsic religiosity did not significantly predict material satisfaction. Extrinsic religiosity predicted increased satisfaction with their religious/spiritual lives (β = .11, p = .03) but was to not related to the other variables. Overall, intrinsic religiosity was related to positive well-being, and extrinsic religiosity was not significantly related to well-being.

Life Aspirations and Well-being

Intrinsic life aspirations predicted increased positive affect (β = .13, p = .01), increased religious satisfaction (β = .10, p < .05), and increased social satisfaction (β = .13, p = .01) (see Table 3). Intrinsic life aspirations did not significantly predict negative affect or material satisfaction. Extrinsic life aspirations predicted increased negative affect (β = .19, p < .001), decreased positive affect (β = −.19, p < .001), decreased religious satisfaction (β = −.23, p < .001), decreased social satisfaction (β = −.16, p < .002), and decreased material satisfaction (β = −.22, p < .001). Overall, intrinsic life aspirations were related to positive outcomes, and extrinsic life aspirations were related to negative outcomes.

Religious Orientation and Life Aspirations

The second set of hypotheses stated that intrinsic religiosity would be positively related to intrinsic aspirations and negatively related to extrinsic aspirations with the opposite being true for extrinsic religiosity. It was found that intrinsic religiosity predicted increased intrinsic life aspirations (β = .09, p < .05) and predicted decreased extrinsic life aspirations (β = −.18, p < .001) (see Table 4). Extrinsic religiosity predicted increased extrinsic life aspirations (β = .18, p < .001) and was not significantly related to intrinsic life aspirations. Therefore, the hypotheses were mostly supported. The last hypothesis was that life aspirations would partially mediate the effects of religious orientation. This, however, was not found to be the case. Using regression analyses, controlling for the effects of intrinsic life aspirations did not significantly affect the strength of relationship between intrinsic religiosity and outcome. If fact, both remained significant in the model, indicating they contribute independent information in the prediction of outcome. Mediational analyses were not conducted with extrinsic religiosity because it was not related to majority of the outcomes. Interestingly, it, a secondary analysis, was found that religious satisfaction did mediate the relationships between intrinsic religiosity and positive and negative affect such that intrinsic religiosity was no longer significant when religious satisfaction was included in the model.

Discussion

We hypothesized that intrinsic religiosity would be related to intrinsic life aspirations and that extrinsic religiosity would be related and extrinsic life aspirations, and that life aspirations would partially mediate the effects of religious orientation on outcome. The findings are mixed. Higher levels of intrinsic religiosity were positively related to positive affect, life satisfaction, and intrinsic life aspirations, and negatively related to negative affect and extrinsic life aspirations. Higher levels of extrinsic religiosity were related to increased extrinsic life aspirations. When examining mediational models, however, both religious orientation and life aspirations remained significant, indicating the religious orientation and life aspirations exert independent effects. It is important to note that for most of the statistically significant relationships, the effect sizes were relatively small.

The results of the study do not provide evidence for using self-determination theory and life aspirations as a framework for understanding the relationships between intrinsic and extrinsic religiosity and outcomes. There is theoretical overlap among the religious orientation and life aspirations (Kasser and Ryan 1993, 1996; Ryan et al. 1993), and this study provides empirical evidence that intrinsic religiosity is positively related to intrinsic life aspirations and negatively related extrinsic life aspirations, and extrinsic religiosity is related to extrinsic life aspirations. However, there appears to be independent pathways through which religious orientation and life aspirations affect outcome. It is possible that life aspirations affect outcome through a sense of satisfaction with current life functioning, whereas religious orientation affects outcome through a sense of satisfaction with spiritual connectedness. A follow-up analysis found that spiritual/religious satisfaction did mediate religious orientation. Future studies are needed to further explore these possibilities.

As discussed in the Introduction, intrinsic and extrinsic motivational styles have an important influence on subjective well-being. This effect may be explained in terms of an inward versus and outward reliance for well-being. An inward reliance for well-being may generally result in realization of goals that are linked to well-being, while an outward reliance for well-being places the responsibility for personal wellness on events that are not necessarily under personal control. For example, less adjustment was evidenced for individuals who held financial success as a more central aspiration than components of well-being such as self-acceptance, affiliation, or community feeling (Kasser and Ahuvia 2002). Kasser and Ryan (2002) noted that “…not all goals are equivalent in terms of their relationship to well-being. When goals for financial success exceeded those for affiliation, self-acceptance, and community feeling, worse psychological adjustment was found” (p. 421). Interestingly, attainment of materialistic goals does not necessarily reduce the negative relationship between materialism and subjective well-being, regardless of level of income (Nickerson et al. 2003). Similarly, intrinsic religiosity may contribute to well-being through the pursuit of spiritual goals, and extrinsic religiosity may inhibit well-being because it takes energy away from pursuit of spiritual goals (Smith et al. 2003).

One potential problem with using the Religious Orientation Index to assess extrinsic religiosity is that its relationship to extrinsic motivation is questionable. Neyrinck et al. (2010) found that although intrinsic religiosity had a strong positive relationship to intrinsic motivation as expected, extrinsic religiosity was not related to extrinsic motivation as defined in self-determination theory (see also Neyrinck et al. 2005; Sheldon et al. 2004). The authors suggest that extrinsic religiosity is more related to goals rather than motivations and therefore does not correlate with the motivations put forward in self-determination theory. In this study, it was found that extrinsic religiosity was related to extrinsic life aspirations. It is possible that engaging in extrinsically oriented goals is what contributes to negative outcomes and not motivation per se, with energy being spent on extrinsic activities robbing energy from more intrinsic goals.

This study has several limitations. First, the study is cross-sectional, so no statements can be made about causality; rather, statements are focused on relationships among variables. Second, the study sample was predominately white, so it is not clear how these findings apply to different ethnic groups. Third, the study sample was predominately Christian, so it is not clear how these findings would apply to people of different religious backgrounds. Future studies could build upon this study using longitudinal research designs to examine how these variables are related over time and sample from a more diverse demographic. Strengths of this study include the fact that it was drawn from a national random probability sample and that participants were carefully assessed on both religious orientation and life aspirations.

In summary, intrinsic and extrinsic religious orientations are related to intrinsic and extrinsic life aspirations, but life aspirations do not mediate the effects of religious orientation on outcome. Instead, life aspirations and religious orientation are independent predictors of outcome and appear to have different pathways through which they affect outcome. Therefore, self-determination theory does not appear to provide a useful framework for understanding why and how intrinsic and extrinsic religiosity has their impact on health and well-being.

References

Allport, G. W., & Ross, J. M. (1967). Personal religious orientation and prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 5, 423–443.

Andrews, F. M., & Robison, J. P. (1991). Measures of subjective wellbeing. In J. P. Robison, P. Shaver, & L. Wrightsman (Eds.), Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes. San Diego: Academic Press.

Chida, Y., Steptoe, A., & Powell, L. H. (2009). Religiosity/spirituality and mortality. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 78, 81–90.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. Journal of Research in Personality, 19, 109–134.

Donahue, M. J. (1985). Intrinsic and extrinsic religiousness: Review and meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48, 400–419.

Kahle, L. (1983). Social values and social change: Adaptation to life in America. New York: Praeger.

Kahle, L. R. (1996). Social values and consumer behavior: Research from the list of values. In C. Seligman, J. M. Olson, & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), The psychology of values: The Ontario Symposium (Vol. 8, pp. 135–151). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Kasser, T., & Ahuvia, A. (2002). Materialistic values and well-being in business students. European Journal of Social Psychology, 32, 137–146.

Kasser, T., & Ryan, R. M. (1993). A dark side of the American dream: Correlates of financial success as a central life aspiration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 410–422.

Kasser, T., & Ryan, R. M. (1996). Further examining the American dream: Differential correlates of intrinsic and intrinsic goals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22, 280–287.

Koenig, L. B., & Vaillant, G. E. (2009). A prospective study of church attendance and health over the lifespan. Health Psychology, 28, 117–124.

McCullough, M. E., Hoyt, W. T., Larson, D. B., & Koenig, H. G. (2000). Religious involvement and mortality: A meta-analytic review. Health Psychology, 19, 211–222.

Neyrinck, B., Lens, W., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2005). Goals and regulations of religiosity: A motivational analysis. In M. L. Maehr & S. Karabenick (Eds.), Advances in motivation and achievement, Vol. 14. Motivation and religion (pp. 77–106). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Neyrinck, B., Lens, W., Vansteenkiste, M., & Soenens, B. (2010). Updating Allport’s and Batson’s framework of religious orientations: A reevaluation from the perspective of Self-Determination Theory and Wulff’s Social Cognitive Model. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 49, 425–438.

Nickerson, C., Schwarz, N., Diener, E., & Kahneman, D. (2003). Zeroing on the dark side of the American Dream: A closer look at the negative consequences of the goal for financial success. Psychological Science, 14, 531–536.

Pargament, K. I., Zinnbauer, B. J., Scott, A. B., Butter, E. M., Zerowin, J., & Stanik, P. (2003). Red flags and religious coping: Identifying some religious warning signs among people in crisis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 59, 1335–1348.

Richins, M. L., & Dawson, S. (1992). A consumer values orientation for materialism and its measurement: Scale development and validation. Journal of Consumer Research, 19, 303–316.

Rokeach, T. (1973). The nature of human values. New York: Free Press.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-Determination Theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55, 68–78.

Ryan, R. M., Rigby, S., & King, K. (1993). Two types of religious internalization and their relations to religious orientations and mental health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 586–596.

Sheldon, K. M., Ryan, R. M., Deci, E. L., & Kasser, T. (2004). The independent effects of goal contents and motives on wellbeing: It’s both what you pursue and why you pursue it. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 475–486.

Smith, T. B., McCullough, M. E., & Poll, J. (2003). Religiousness and depression: Evidence for a main effect and the moderating influence of stress life events. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 614–636.

Steffen, P. R. (2012). Approaching religiosity/spirituality and health from the eudaimonic perspective. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 6, 70–82. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00411.x.

Steffen, P. R. (2013). Perfectionism and life aspirations in intrinsically and extrinsically oriented individuals. Journal of Religion and Health,. doi:10.1007/s10943-013-9692-3.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Steffen, P.R., Clayton, S. & Swinyard, W. Religious Orientation and Life Aspirations. J Relig Health 54, 470–479 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-014-9825-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-014-9825-3