Abstract

Young people in sub-Saharan Africa are at the centre of the global HIV epidemic as they account for a disproportionate share of new infections. Their vulnerability to HIV has been attributed to a myriad of factors, in particular, risky sexual behaviours. While economic factors are important, increasing attention has been devoted to religion on the discourse on sexual decision-making because religious values provide a perspective on life that often conflicts with risky sexual behaviours. Given the centrality of religion in the African social fabric, this study assesses the relationship between adolescent religiousness and involvement in risky sexual behaviours using data from the informal settlements of Nairobi. Guided by social control theory, the paper explores if and how religion and religiosity affect sexual risk-taking among adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Twenty-five years after the first diagnosis in the United States, HIV/AIDS has become a global pandemic, with sub-Saharan Africa as the epicentre. Although no one knows the exact numbers, UNAIDS and WHO estimates that in 2008, the region accounted for more than two-thirds of HIV infections worldwide, 68% of new HIV infections among adults, and 72% of AIDS-related deaths around the world (UNAIDS and WHO UNAIDS and 2009). Although concerted educational campaigns have contributed to about 15% decline in new cases since 2001 (BBC News 2009), yet the absolute numbers are still overwhelming. The UNAIDS and WHO estimate that about 1.9 million Africans became newly infected in 2008 although prevalence rates vary greatly from as low as 1% of the adult population in Senegal and Somalia to as high as 15–25% in Botswana, Swaziland, South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe. While Kenya is mentioned in the 2008 AIDS report as one of the few countries in the region with significant returns on investment in HIV prevention, the current prevalence rate of 7.1–8.5% is still high.

Young people are at the centre of the global HIV epidemic. While they make up a quarter of the 38 million people living with the disease, they account for about half of all new adult infections. According to UNFPA (2005) estimates, about 6,000 youths are infected with the virus daily. The vulnerability of the youth in sub-Saharan Africa is particularly disturbing as they account for almost two-thirds of the youth in the world living with the disease. Recent data in several countries indicate that 5% of young women aged 15–24 are infected with the virus. While the percentage of young adults who correctly identify ways of preventing the sexual transmission of HIV and who reject major misconceptions about HIV transmission has increased in recent years in Kenya, there is an alarming degree of misinformation and lack of knowledge on vulnerability.

Although intravenous drug use and homosexual activities are becoming important factors, heterosexual relationships remain central to HIV transmission in the region. The susceptibility of young people to HIV infection has been attributed to a myriad of factors, in particular, involvement in risky sexual behaviours. Not surprisingly, the last decade has witnessed an upsurge of interest on adolescent sexual behaviour with most indicating that adolescents in many countries do not engage in safe sex practices (Buga 1996; Abdulraheem and Fawlole 2009; Kabiru and Orpinas 2009; Gyimah et al. 2010; Tenkorang et al. 2010). The accumulating evidence notwithstanding, these studies often conceal the heterogeneity among the youth. For example, unprecedented urban growth compounded by poor governance and economic stagnation has created a new face of poverty characterized by a significant proportion of urban populations living in over-crowded informal settlements. Estimates by UN-Habitat suggest that about 70% of all urban residents of sub-Saharan Africa live in slums largely characterized by overcrowding and poverty. Young people make up a considerable proportion of the slum population because of the history of high fertility and the selective rural–urban migration in search of illusive employment opportunities. While the age at sexual initiation has declined in many parts of urban sub-Saharan Africa, the age at first marriage has increased over time (Brockerhoff and Brennan 1998; White et al. 2000), resulting in a lengthy exposure during which adolescents are susceptible to poor sexual decision-making. For instance, adolescents in the slums of Nairobi have been found to initiate sex about 3 years earlier and are 2 times more likely to have multiple sexual partners than their counterparts in the non-slum parts of the city (Zulu et al. 2002).

Because of the concerns about STDs as well as adolescent pregnancy, the circumstances surrounding the high-risk sexual behaviours of adolescents need better understanding to inform public policy. Although economic factors are relevant in understanding the vulnerability of the youth, increasing attention has also been devoted to the relevance of religion in this discourse (Bediako 1995; Gifford 1994; Jenkins 2002; Gyimah et al. 2010). This is because religious values provide a perspective on life that often conflicts with risky sexual behaviours. In the US, for example, the National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy identified attachment to religious institutions as one of the antecedents to reduce sexual risk-taking (Kirby 1999) and policy makers have been interested in faith-based initiatives to address the vulnerabilities of the youth. This is salient in the African context also given the centrality of religion to its social fabric (Mbiti 1992; Gyimah 2007; Gyimah et al. 2008). As the BBC News 2005 survey indicates, three quarters of respondents in Africa identified religious leaders as the most trusted group, compared to only a third worldwide. Asked who had had the most influence on their decision-making over the past year, a significantly higher proportion of respondents in Africa indicated religious leaders. This suggests that religion may be uniquely situated in the fight against AIDS by influencing sexual decision and providing access to information on prevention. In rural Uganda, for example, Forster and Furley (1989) found that churches were the predominant institutional channels of information on HIV, particularly among women.

The relevance of religion to the discourse on HIV/AIDS could also be attributed in part to the belief that AIDS can be transmitted through spiritual means or as a divine punishment (see, for example, Yamba 1997; Trinitapoli and Regnerus 2006). In Zenebe’s (2007) study in Ethiopia, some informants were of the opinion that a person with HIV/AIDS is one punished by God because he/she was tempted by his/her flesh to engage in an immoral sexual act. In a recent study among Nigerian youth, a quarter of respondents indicated ‘wrath of God’ as the cause of HIV/AIDS compared with only 15% who correctly attributed it to a virus (Abdulraheem and Fawlole 2009). Some interpret the rising HIV/AIDS prevalence as evidence of sexual promiscuity and moral decadence and consider religion as uniquely situated in the fight against the pandemic (Garner 2000; Trinitapoli and Regnerus 2006; Adogame 2007).

As Trinitapoli and Regnerus (2006) point out, notwithstanding the high levels of religious participation in sub-Saharan Africa, high-quality data on this topic are scarce. Although religion-related variables appear in a fairly substantial number of studies examining the antecedents of adolescent sexual attitudes and behaviours, they are often treated as control rather than independent variables (Zulu et al. 2002; Kabiru and Orpinas 2009). Moreover, existing research on the subject has been constrained by the lack of multiple measures on religion (see, for example, Parkhurst 2001; Trinitapoli and Regnerus 2006; Gyimah et al. 2010). Although some argue that religious affiliation per se makes a difference in the discourse on social and reproductive outcomes (see, for example, Lehrer 2004), it is challenging to quantify aspects of human experience as broad and diffuse as religion with only one variable. Additionally, the single-dimensional measures of religion and religious involvement have been shown to suffer from numerous problems yet, multidimensional measures of religion have been uncommon in the literature on adolescent sexual behaviour in sub-Saharan Africa. Using different but somewhat related dimensions of religion (affiliation, practice, beliefs, religiosity), the present study extends existing research by examining the nature of the relationship between religion and risky sexual behaviours, conceptualized in this study as the co-occurrence of multiple sexual partnership and early sexual intercourse among adolescents in Nairobi, Kenya.

Religion and Sexual Risk-Taking

Extant research on religion and sexual risk-taking draws largely on particularized theology and selectivity theses. The selectivity school contends that the relationship between them is somewhat ambiguous and that religious variations in behaviour reflect differential access to social and human capital than religion per se. To the particularized theology school, religion has an independent effect and usually operates through social control and social support theories. A social control perspective assumes that social institutions such as family, school, and religion promote values that are consistent with conventional behaviour because they socialize members to adopt the norms and values of the group. Although Hirschi (1969) did not include religion as one of the social institutions in his original model, religion can be viewed as a conventional institution of social bonding that deters individuals from becoming involved in problem behaviour. Thus, adolescents strongly bonded to conventional society through attachment to a religious body will be less inclined to engage in deviant behaviour than those unaffiliated. This conception derives, in part, from Durkheim’s notion of religion as an institution of social control.

As Hummer et al. (2004) point out, a key function of religious communities is to shape the norms of individual members through behavioural regulations that are specified in sacred teachings, reinforced through authoritative messages from congregational leaders and solidified through social interactions in the religious community. Sexual behaviour could be influenced either positively or negatively through doctrinal teachings and prohibitions on sexuality and sexual behaviour in general. For instance, discouraging condom use, opposing sex education and giving religious interpretations to the spread of the virus could undermine AIDS prevention (World Bank 1997).

To the extent that different religions have different sanctions on what is acceptable behaviour, one could expect denominational differences in sexual behaviour. While all religious faiths proscribe risky sexual relations, there is some variation in their level of condemnation as expressed in official doctrines. Conservative denominations often internalize negative messages and sanctions against sexual behaviour more than liberal denominations. For these religions, non-marital sexual relations are wrong, and those who engage in such behaviour are sinners who can be saved only through penitence. The ‘born-again’ experience of Pentecostalism has also been found to associate with changes in sexual behaviours (Chesnut 1997; Maxwell 1998). As Maxwell (1998) notes, once individuals become ‘born-again’, they are brought into a ‘community of the saved’ where they strive to maintain a state of inner purity necessary to receive empowerment from the Holy Spirit. According to Rohrbaugh and Jessor (1975), religion generates social control by embedding the individual in an ‘organized sanctioning network’ that is supportive of conventional activities and opposed to unconventional ones; making the individual sensitive to moral issues and acceptable standards of behaviour; offering a deity as a source of punishment and wrath; and generating devoutness, thus creating an ‘obedience orientation’.

Religion and faith-based organizations may also be uniquely situated in diffusion of ideas about AIDS prevention through social capital (Rutenberg and Watkins 1997; Agadjanian 2001). In South Africa, Garner (2000) found that some Christian churches offered members the potential for significant reductions in extra- and pre-marital sexual activity. For adolescents, participation in religious groups provides access to a broader range of resources than would otherwise be available and may subsequently reduce the likelihood of engaging in risky sexual behaviour. Moreover, holding certain religious beliefs and participating in religious activities may increase self-efficacy, self-esteem and pro-social behaviours that may in turn reduce the susceptibility of engaging in risky sexual behaviour. However, there is some concern that the emphasis on non-use of condoms, celibacy, marital fidelity and abstinence propagated by certain churches may not be viable options for women with no feasible alternatives. The question this study addresses is how much of the religious variation in risky sexual behaviour among adolescents, if any, can be explained by observed socio-economic and bio-demographic factors. To test whether religion has an independent effect, a series of nested models with and without controls for socio-demographic variables will be estimated.

Data and Methods

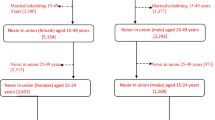

This paper draws on data collected under the Transition-To-Adulthood (TTA) project nested on the Nairobi Urban Health and Demographic Surveillance System (NUHDSS) conducted by the African Population and Health Research Centre (APHRC). The NUHDSS covers about 60,000 people living in 23,000 households in Korogocho and Viwandani informal settlements in Nairobi city. The NUHDSS and TTA have ethical approval from the Kenya Medical Research Institute’s ethical review board. In addition, all fieldworkers are trained on research ethics. The TTA’s general objective is to identify protective and risk factors in the lives of adolescents growing up in these two informal settlements in Nairobi and to examine how those factors influence their transition to adulthood. Adolescents were randomly selected within the households in the study area using records of residents in the NUHDSS for the year 2007. A comprehensive questionnaire was administered to adolescents and included questions covering reproductive aspirations (e.g. parenthood and marriage); key health and other concerns (e.g. worry about HIV/AIDS, getting a job, marriage, finishing school, employment); living arrangements and nature of interactions with parents, guardians, teachers, and peers; involvement in youth groups (e.g. religious and social groups); involvement in risky behaviours (e.g. early sexual debut and delinquency). The complete questionnaire was translated from English to Swahili and administered in Swahili, the language most spoken in the study area.

Measures

The outcome variable for this study is conceptualized as involvement in risky sexual behaviour that has been found paramount in the spread of the HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa. While the literature is replete with various conceptualizations of risky sexual behaviour (Tenkorang et al. 2010; Dimbuene and Kuate Defo 2010; Gyimah et al. 2010; Stephenson 2009) in this paper, it is defined as the co-occurrence of early sex (before age 16) and involvement with multiple sexual partners in the last year. Respondents were asked the number of sexual partners in the last 12 months and age at first sexFootnote 1 from which we created a binary variable on their co-occurrence.

It has been argued that frequency of attending religious services as well as denominational affiliation may not be solely under the control of adolescents themselves but perhaps are proxies for parental control. Taking this into account, we used four related measures (affiliation, practice, beliefs/spirituality and religiosity) each of which ascertains a different but somewhat related dimension of religious involvement and commitment. The first was obtained from questions that asked adolescents about their religious affiliation and identified as: Catholic, Protestant, Pentecostal, Other Christian, Moslem, Other religion and No religion. Given the differential emphasis on morality and sanctions governing sexual misconduct, we expect significant denominational differences at least at the bivariate level. Religious practice was derived from questions that asked adolescents whether certain practices/beliefs central to their faiths are followed. Catholics were asked whether they have been to a confession or prayed with rosary in the last year; Protestants and Pentecostals were asked whether they consider themselves born again; and Moslems were asked to rate the extent to which they observe certain practices central to the Islamic faith such as praying 5 times a day, fasting during Ramadan, attending Friday prayers, practicing Zakat and abstaining from alcohol and pork. On the basis of these questions, we created a binary measure of members’ commitment to religious doctrines.

We also included variables that capture religiosity (frequency of worship) and beliefs. While both deal with the divine and involve practices aimed at increasing feelings of connection with a supreme power, there are important differences. As Boudreaux et al. (2002) point out, whereas religiosity is seen as more of a public, man-made, formal and socialized practice, spirituality/belief is characterized as more private, naturally occurring, unstructured and independent from formal institutions. Religious belief/spirituality was ascertained from questions asking adolescents to rate, on a 1–4 scale (not important, somewhat important, important and very important), how important it is to them to: (1) belief in God, (2) rely on religious teachings, (3) rely on religious beliefs and (4) turn to prayers when you have a problem. Adolescents who indicated no religious affiliation were not asked these questions, but we assigned them a score of zero on each of the questions. Exploratory analysis suggested a high correlation of more than 0.85 for each pair. Given this, we created a standardized index of religious beliefs from the four questions with an average inter-item correlation of 0.88 and alpha reliability of 0.96. Our measure of religiosity was based on the frequency of religious attendance in the past month measured as never, once, 2–3 times, 4 times and more than 4 times.

Controls included in our models are socio-economic and demographic factors known to affect sexual behaviours. These include household wealth, current age, living with parents, educational attainment, neighbourhood of residence, ethnicity and gender. As with most population-based surveys on sexual behaviour, it is important to recognize that self-reports on sensitive questions bearing on sexuality could be biased through under or over reporting (Zaba et al. 2004). Also, because the questions deal with religion at the time of the survey, we are unable to address the issue of religious switching over time on sexual behaviour, a limitation that is best handled with longitudinal data.

Analytic Strategy

The cases are unevenly distributed over the binary dependent variable (risky sexual behaviour), indicating that the logit or probit link functions which assume a symmetrical distribution may produce biased estimates. We therefore chose a complementary log–log regression, which is better suited for asymmetrical distribution (Long 1997). For intuitive interpretation, the estimated coefficients are transformed through exponentiation where coefficients greater than one indicate higher likelihood of engaging in risky sexual behaviour while the reverse holds if the coefficient is less than 1. We begin the analysis with a description of all the theoretically relevant variables. We then present a bivariate analysis involving each of the covariates and the outcome variable followed by a chi-square analysis on denominational differences on the control variables. In the multivariate models, we estimate a series of sequential model to assess if and how the denominational differences can be explained and to evaluate the robustness of the religion measures.

Findings and Discussion

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of the variables. About 14% of respondents are classified in high sexual risk category with females significantly more likely than males to be identified as such. The mean age is about 16.7 (SD = 3), but females are slightly younger than the males. Christianity is the dominant religion accounting for more than three quarters of the sample. Among Christians, there is an almost equal percentage of Catholics, Protestants and Pentecostals. Moslems constitute about 11.5% of the sample and there appears to be no difference between males and females in terms of affiliation. While about 8% has no affiliation with any religion, males adolescents are more likely to identify as such compared with females. Overall, about 60% of respondents indicated that they follow the tenets/practices of their religion but females are more likely to do so than males. The male–female differences are consistent with research elsewhere, which indicates that females participate more regularly in religious services and report frequently that religion is important in their daily lives. Various explanations have been offered to account for this gender difference including structural location, gender role socialization, personality differences and risk-aversion (Miller and Stark 2002; Hoffmann 2009).

Table 2 shows bivariate analyses of sexual risk-taking and the theoretically relevant covariates. In general, adolescents who identify with any religion have a lower risk compared with the unaffiliated. For example, adolescents who are Catholics are about 40% less likely to indulge in risky sexual behaviour compared with those with no religious affiliation. The relatively low risk among those affiliated with a religious institution could be due to exposure to doctrinal teachings on immorality and the governing sanctions. Affiliated individuals are more likely to abide by the norms and values of the religious groups to which they belong. Although postestimation Wald tests indicated that Moslems adolescents had a significantly lower risk than those of other religions, there were no significant differences among Christians (Catholic, Protestant, Pentecostal, and Other Christians). The low risk among Moslems could be due to the stricter sanctions governing sexual conduct. Sexual misconduct in the form of premarital sex or sex outside marriage is punishable under the Sharia and the case of the seventeen-year-old girl in Zamfara, Nigeria, is still fresh in the mind of many (Adepegba 2001). There is also evidence that those involved in religious practices as well as those with higher levels of religious beliefs are less likely to engage in risky sexual behaviour consistent with extant research.

Educational attainment is also a significant predictor of sexual risk-taking at the bivariate level, with highest risk among those do not know their level of education as well as those with at least secondary education. Extant research mostly in the West suggests that adolescents from two parent families are less likely to be involved in risky sexual behaviours than their peers from other familial arrangements. The structural-functionalist school, for instance, suggests that adolescents living with both biological parents are better adjusted psychosocially compared with those living in other familial arrangements and are therefore less likely to become sexually active. Evidence from Table 2 confirms that adolescents who live with their parents are about 80% less likely to engage in risky sexual behaviours compared with those in other familial situations, which is consistent with recent findings in Nairobi (Kabiru and Orpinas 2009). Culture is always an important variable on issues of sexuality and sexual behaviour in sub-Saharan Africa (Caldwell 2000; Awusabo-Asare et al. 2004). Although racially homogenous, the adolescents in our study come from diverse ethnic groups where norms regulating sexual behaviour may be different. Although the Luhya and Luo have a higher risk compared with the Kikuyu, the effects are not statistically significant. Males as well as those from the poorest household have the lowest risk.

Further analysis (not produced here), however, indicates statistically significant relationship between the background factors and religious affiliation. For instance, about 17% of Other Christians have at least secondary level education compared with only 6% of Moslems and the unaffiliated. Similarly, the proportion of adolescents that lives with parents is highest among Moslems and least among those with no affiliation. Against this backdrop, we estimated series of models and explored if affiliation had a salutary effect on risky sexual behaviour in a multivariate context and the theoretical pathways. Revisiting our theoretical framework, the characteristics thesis argues that denominational differences are mostly a function of socio-economic differences while the particularized thesis argues that religion has a salutary effect. Based on the social control theory, the effect of religion on sexual behaviour largely operates through beliefs and teachings on when and with whom sex is appropriate. Four models are presented in Table 3 to explore these. Model 1 examines adjusted effects of the background variables that are substantively similar to those in Table 2. In Model 2, we test the characteristics hypothesis by controlling for the socio-economic variables and evaluate the robustness of the denominational differences. It is important to note that although the addition of the socio-economic variables did not diminish the significance of the denominational differences, the attenuation of the coefficients suggests that some of the differences could be attributed to background factors. Model 3 evaluates the particularized theology thesis and tests whether the denominational differences are a function of religious practice, religious beliefs and religiosity. The findings are consistent with this thesis and suggest that denominational differences are mostly a function of practice, beliefs and frequency of worship. From Model 3, we observe that frequent worshippers as well as those who follow the tenets of their religion have a significantly lower risk of engaging in risky sexual behaviour. What is surprising, however, is the inverse relationship between the index of beliefs and involvement in risky behaviour although the relationship is not statistically significant.

Summary and Conclusion

In this paper, we examined religiosity and indulgence in risky sexual behaviour among adolescents in the informal settlements of Nairobi. Guided by several theoretical models, we found significant denominational differences at the bivariate level. Social control theory suggests that affiliation with a religious organization that espouses conventional values (to varying degrees) will make followers less likely to be predisposed to deviant behaviour than those unaffiliated. Following this, we expected the unaffiliated to be more inclined to engage in risky sexual behaviour than those affiliated with any religious faith, which was supported at the bivariate level.

In the multivariate models, we explored how the denominational differences in risky sexual behaviour could be explained. In accordance with the characteristics hypothesis, we tested whether the differences could be explained through the background factors. There were still significant differences in the presence of the socio-economic variables which suggested that the denominational differences could not be solely attributed to the socio-economic factors as the characteristics hypothesis suggests. Consistent with the particularized theology thesis however, we found that the denominational differences in risky sexual behaviour were the result of beliefs, practice and frequency of worship, which contrast with recent work among men in Ghana (Gyimah et al. 2010).

It needs emphasizing that the likelihood of contracting HIV among adolescents depends largely on how able they are to avoid involvement in risky sexual behaviour. While HIV/AIDS is probably the most important consequence of adolescent risky sexual behaviour, it is also important to mention unwanted pregnancies and their associated impact on schooling and the health. This paper has shown how crucial religion is to this discourse in that adolescents who practice the tenets of their religion as well as those that attend religious service regularly were found less likely to indulge in risky sexual behaviour. It is likely that those who attend services regularly regardless of denomination will be more exposed to important messages on morality on when and with whom sex is appropriate. For those interested in sponsoring faith-based initiatives, this calls for more support for religious bodies in the fight against HIV. All religious bodies can be supported to engage in the education of their adolescents on sex-related issues.

Besides religion, the final model also indicated some significant associations. Older adolescents were more likely to engage in risky sexual behaviour that probably reflects biological maturity, exposure and social readiness influence. Similar to studies elsewhere, adolescents who live with their parents were significantly less likely to engage in risky behaviour compared with those in other familial arrangements. This is often explained through lack of parental supervision and support social learning, and social control. For instance, parents who live with their adolescent children may have better opportunities to monitor and supervise the activities of their adolescents. The major limitation of the study deals with the cross-sectional nature of the data and the possibility of selection bias. Given that religious participation is a choice (although less so among adolescents), it is likely that an underlying personality factor may explain both religious involvement and outcomes like sexual activity. Overall, however, the findings of this study indicate the salience of religious factors. This implies that we should not minimize the role of religion while considering viable sexuality programs for the youth. Although we are not clear which aspect of religion is more influential to an individual’s behavioural change, it is promising that religiosity may be incorporated with adolescent sexuality programs. There is the need to involve religious organizations in the design and implementation of programmes on changes in sexual behaviour.

Notes

Unfortunately, no information was solicited on the use of condoms in the most recent sexual encounter so we could not use that as an indication of risky behavior.

References

Abdulraheem, I. S., & Fawlole, I. O. (2009). Young people’s sexual risk behaviors in Nigeria. Journal of Adolescent Research, 24(4), 505–527.

Adepegba, B. (2001). Canada rises up for Sharia convict, PM News, Lagos 2 January 2001.

Adogame, A. (2007). HIV/AIDS support and African Pentecostalism: The case of the redeemed Christian Church of God (RCCG). Journal of Health Psychology, 12(3), 475–483.

Agadjanian, V. (2001). Religion, social milieu, and contraceptive revolution. Population Studies, 55, 135–148.

Awusabo-Asare, K., Abane, A. M., & Kumi-Kyereme, A. (2004). Adolescent sexual and reproductive health: A synthesis of research evidence. New York: The Alan Guttmacher Institute, No. 13.

BBC News. (2005). Africans trust religious leaders. Available at http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/africa/4246754.stm. Accessed 4 Sept 2005.

BBC News. (2009). HIV infections and deaths fall as drugs have impact. Available at http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/8375297.stm. Accessed 24 Nov 2009.

Bediako, K. (1995). Christianity in Africa: Renewal of a non-western religion. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Boudreaux, E. D., O’Hea, E. L., & Chasuk, R. (2002). Spirituality and healing: An alternative way of thinking. Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice, 29, 1–16.

Brockerhoff, M., & Brennan, E. (1998). The poverty of cities in developing countries. Population and Development Review, 24(1), 75–114.

Buga, G. (1996). Sexual behavior, contraceptive practice and reproductive health among school adolescents in rural Transkei. South African Medical Journal, 86, 523–527.

Caldwell, J. (2000). Rethinking the African AIDS epidemic. Population and Development Review, 26(1), 117–135.

Chesnut, R. A. (1997). Born again in Brazil: The Pentecostal Boom and the Pathogens of Poverty. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Dimbuene, Z. T., & Kuate Defo, B. (2010). Risky sexual behavior among unmarried young people in Cameroon: Another look at family environment. Journal of Biosocial Science, 43(2), 129–153.

Forster, S. J., & Furley, K. E. (1989). 1988 public awareness survey on AIDS and condoms in Uganda. AIDS, 3, 147.

Garner, R. C. (2000). Safe sect? Dynamic religion and AIDS in South Africa. Journal of Modern African Studies, 38, 41–69.

Gifford, P. (1994). Some recent developments in African Christianity. African Affairs, 93, 513–534.

Gyimah, S. O. (2007). What has faith got to do with it? Religion and child survival in Ghana. Journal of Biosocial Science, 39(6), 923–937.

Gyimah, S. O., Takyi, B., & Eric Tenkorang, E. (2008). Denominational affiliation and fertility behavior in an African context: An examination of couple data from Ghana. Journal of Biosocial Science, 40(3), 445–458.

Gyimah, S. O., Tenkorang, E., Takyi, B., Adjei, J., & Fosu, G. (2010). Religion, HIV/AIDS and sexual-risk taking among men in Ghana. Journal of Biosocial Science, 42, 531–547.

Hirschi, T. (1969). Causes of delinquency. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hoffmann, J. P. (2009). Gender, risk, and religiousness: Can power control provide the theory? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 48(2), 232–240.

Hummer, R. A., Ellison, C., Rogers, R. G., Moulton, B. E., & Romero, R. R. (2004). Religious involvement and adult mortality in the United States: Review and perspectives. Southern Medical Journal, 97(12), 1223–1230.

Jenkins, P. (2002). The next Christendom: The coming of global Christianity. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Kabiru, C. W., & Orpinas, P. (2009). Factors associated with sexual activity among high-school students in Nairobi, Kenya. Journal of Adolescence, 32(4), 1023–1039.

Kirby, D. (1999). Looking for reasons why: The antecedents of adolescent sexual risk-taking, pregnancy, and childbearing. Washington, DC: National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy.

Lehrer, E. L. (2004). The role of religion in union formation: An economic perspective. Population Research and Policy Review, 23, 161–185.

Long, J. S. (1997). Regression models for categorical and limited dependent variables. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Maxwell, D. (1998). Delivered from the spirit of poverty? Pentecostalism, prosperity and modernity in Zimbabwe. Journal of Religion in Africa, 28(3), 350–373.

Mbiti, J. S. (1992). African religions and philosophy. London: Heinemann.

Miller, A. S., & Stark, R. (2002). Gender and religiousness: Can socialization explanations be saved? American Journal of Sociology, 107(6), 1399–1423.

Parkhurst, J. (2001). The crisis of AIDS and the politics of response: The case of Uganda. International Relations, 15, 69–87.

Rohrbaugh, J., & Jessor, R. (1975). Religiosity in youth: A personal control against deviant behavior. Journal of Personality, 43, 136–155.

Rutenberg, N., & Watkins, S. (1997). The buzz outside the clinics: Conversations and contraception in Nyanza Province, Kenya. Studies in Family Planning, 28(4), 290–307.

Stephenson, R. (2009). Stephenson, community influences on young people’s sexual behavior in 3 African countries. American Journal of Public Health, 99(1), 102–109.

Tenkorang, E. Y., Rajulton F., & Maticka-Tyndale, E. (2010). A multi-level analysis of risk perception, poverty and sexual risk-taking among young people in Cape Town, South Africa. Health and Place, 17(2), 525–535.

Trinitapoli, J. A., & Regnerus, M. D. (2006). Religion and HIV risk behaviors among married men: Initial results from a study in rural sub-Saharan Africa. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 45(4), 505–528.

UNAIDS and WHO. (2008). Sub-Saharan Africa: AIDS epidemic update regional summary. Available at http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2008/jc1526_epibriefs_ssafrica_en.pdf. Accessed 18 July 2008.

UNAIDS and WHO. (2009). AIDS epidemic update. http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2009/2009_epidemic_update_en.pdf.

UNFPA. (2005). Youth and HIV/AIDS fact sheet. http://www.unfpa.org/swp/2005/presskit/factsheets/facts_youth.htm#ftn1.

White, R., Cleland, J., & Carael, M. (2000). Links between premarital sexual behaviour and extramarital intercourse: A multi-site analysis. AIDS, 14(15), 2323–2331.

World Bank. (1997). Confronting AIDS: Public priorities in a global epidemic. New York: Oxford University Press.

Yamba, B. (1997). Cosmologies in turmoil: Witchfinding and AIDS in Chiawa, Zambia. Africa, 67, 200–223.

Zaba, B., Pisani, E., Slaymaker, E., & Boerma, T. J. (2004). Age at first sex: Understanding recent trends in African demographic surveys. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 80, 28–35.

Zenebe, M. (2007). Intersection between religion and HIV/AIDS in Addis Ababa: Some contradictions and paradoxes. Paper presented at AEGIS Conference; Leiden, NL.

Zulu, E. M., Dodoo, F. N.-A., & Ezeh, A. C. (2002). Sexual risk-taking in the slums of Nairobi, Kenya, 1993–1998. Population Studies, 56(3), 311–323.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada’s standard research grant to Stephen. The study was initiated while Stephen was a sabbatical fellow at the APHRC, Nairobi. The Transitions-To-Adulthood study is part of a larger project on Urbanization, Poverty and Health Dynamics at APHRC funded by the Wellcome Trust. We are grateful to the colleagues at APHRC for their contributions and the adolescents in the study communities for participating in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Obeng Gyimah, S., Kodzi, I., Emina, J. et al. Adolescent Sexual Risk-Taking in the Informal Settlements of Nairobi, Kenya: Understanding the Contributions of Religion. J Relig Health 53, 13–26 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-012-9580-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-012-9580-2