Abstract

Research largely shows that religion and spirituality have a positive correlation to psychological well-being. However, there has been a great deal of confusion and debate over their operational definitions. This study attempted to delineate the two constructs and categorise participants into different groups based on measured levels of religious involvement and spirituality. The groups were then scored against specific measures of well-being. A total of 205 participants from a wide range of religious affiliations and faith groups were recruited from various religious institutions and spiritual meetings. They were assigned to one of four groups with the following characteristics: (1) a high level of religious involvement and spirituality, (2) a low level of religious involvement with a high level of spirituality, (3) a high level of religious involvement with a low level of spirituality, and (4) a low level of religious involvement and spirituality. Multiple comparisons were made between the groups on three measures of psychological well-being: levels of self-actualisation, meaning in life, and personal growth initiative. As predicted, it was discovered that, aside from a few exceptions, groups (1) and (2) obtained higher scores on all three measures. As such, these results confirm the importance of spirituality on psychological well-being, regardless of whether it is experienced through religious participation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

After decades of empirical research, there is substantial evidence that religion and spirituality are strongly associated with mental health and psychological well-being (e.g., Chamberlain and Zika 1992; Hill and Pargament 2003). It is widely assumed that religion plays a positive role in providing a sense of identity, a network of social support, and a coherent framework for responding to existential questions (Elliott and Hayward 2007). It can help cope with negative life events or chronic illness (see Pargament 1997) and lead to a sense of shared understanding of a loss or a trauma (Ellens 2007). It can also lead to protective effects against suicide or substance misuse (Moreira-Almeida et al. 2006). Biblical stories and their meaning have aided the development and insights of psychoanalysis, particularly the use of images and symbols in dreams, personality traits, and the unconscious (see chapter 2, Rollins 1999). Yet, individuals who take their religion seriously can also exhibit poorer mental health (Greenway, Meagan, Turnbull and Milne 2007). This is because it can be ‘judgemental, alienating and exclusive’ (Williams and Sternthal 2007) and lead to stress or guilt through nonconformity (Trenholm et al. 1998). Mentally ill patients are at higher risk of mortality when they experience religious doubts (Pargament et al. 2001). There have been extensive reviews on the various mechanisms through which religion is beneficial, as well as detrimental, on specific aspects of psychological health (Pargament 1997; Pargament et al. 1998; Schumaker 1992). More recent research that has more finely delineated the constructs of religion and spirituality points to a largely positive association with psychological well-being (Hill and Pargament 2003).

Conceptualising and Measuring Religion and Spirituality

Despite the attention given to the scientific study of religion and spirituality, there has been a great deal of confusion over the classification of the two terms (Zinnbauer et al. 1997; Hill et al. 2000). The last century has witnessed a variety of definitions, there traditionally being no explicit distinction between the two. This lack of consensus has presented a critical challenge in the field, a degree of agreement being necessary to produce consistent findings to allow for future progress (Zinnbauer and Pargament 2005). The separation of the two terms was originally prompted by the rise in secularism in the mid-1900s. As a result, spirituality became separated from religion and began to acquire distinct connotations. Due to its association with the personal experiences of the transcendent, spirituality began to be regarded in a more positive light, while religion with its formal structure, prescribed theology and rituals restricted such experiences (Zinnbauer et al. 1997). This polarisation of the two terms is documented extensively in literature (e.g., Hill et al. 2000; Miller and Thoresen 2003, Zinnbauer and Pargament (2005, p. 23). Spirituality is used to describe an inner, subjective experience that ‘makes us feel a strong interest in understanding the meaning of things in life’ (Ellens 2008, p. 1). Ellens comments that spirituality is the longing or internal motivation to seek out anything, be that religious or otherwise. Tart (1975) equally describes spirituality as a vast realm of human potential dealing with ultimate purposes, higher entities, God, love, compassion, and purpose. These definitions reflect a self-motivated urge to gain experience and knowledge of the world or God (see also Vaughan 1991). Religion, however, involves practices engaged in by members of a social organisation (Miller and Thoresen 2003), which refers to the outward worship, creeds, and theology, which reflect an understanding of God and the world (Ellens 2008). Argyle and Beit-Hallahmi (1975) refer to religion as a system of beliefs in a divine and practices of rituals directed towards such a power, while Dollahite (1998) describes religion as a covenant faith community with teachings and narratives that enhance the search for the sacred. Because religion only refers to an outward expression of belief, it has a negative connotation as something which ‘has been made for him by others, communicated to him by tradition, determined to fixed forms by imitation and retained by habit’ (James 1902, p. 24).

Often, however, religion and spirituality go hand-in-hand (Sheldrake 2007). McGrath (1999) suggests ‘there need be no tension between an inwardly appropriated faith and its external observance, in that the latter naturally leads the former’, and Ellens (2008) adds that ‘extrinsic religious behaviour also follows, in turn, from intrinsic experiences of the faith’ (p. 151). Indeed, the two words are overlapping constructs that share some characteristics (Miller and Thoresen 2003) and personality factors (Paloutzian and Park 2005, p. 281). Thus, the polarisation of the two constructs into incompatible opposites has been criticised by researchers. Hill et al. (2000) stated that ‘Both spirituality and religion are complex phenomena, multidimensional in nature, and any single definition is likely to reflect a limited perspective or interest’ (p. 52). The authors argued that past attempts at defining the constructs have often either been too narrow, resulting in operational definitions that have produced empirical research with limited value, or too broad, resulting in a loss of clear distinction between the two.

Past efforts to identify measures of spirituality minimised or excluded religion and revealed over 100 self-reported instruments that share little agreement of its characteristics and expression (MacDonald and Holland 2003). More thorough investigation has confirmed this, indicating that they lack common agreement on the main dimensions of spirituality (MacDonald 2000). Indeed, questionnaire measures of spirituality have suffered criticism of being varied in their conceptual basis (Seidlitz et al. 2002). Piedmont (2001) addressed concerns over the psychometric integrity of these constructs and their lack of validity evidence. He questioned ‘whether these constructs represented new aspects of psychological functioning or whether they were just a repackaging of already established individual difference variables’ (p. 4). He attempted to resolve these issues by developing the ‘Spiritual Transcendence Scale’ (STS) (1999, 2001). The STS is particularly useful as it applies across cultures and faiths to represent a spirituality shared across these groups (Piedmont and Leach 2002; Piedmont 2007). The STS consisted of three scales: Prayer fulfilment, feelings of joy and contentment that result from personal encounters with a transcendent reality; Universality, a belief in the unitive nature of life; and Connectedness, a belief that one is part of a larger human ensemble (Piedmont 1999).

Background for the Present Study

Hill et al. (2000) developed a set of criteria for defining religion and spirituality that they suggested could be used in future research. Their criteria emphasised that central to the experience of both religion and spirituality is a search for the sacred; ‘sacred’ being defined as a divine being, divine object, Ultimate Reality, or Ultimate Truth. William Paden (2005, p. 210) clarifies ‘the sacred refers to those objects which to the insider seem endowed with superhuman power and authority… Any religion is a system of ways of experiencing the sacred’. Hill and his colleagues also referred to the term ‘search’, which involves a number of processes. This includes the attempt to identify what is sacred, to articulate, at least to oneself, what one has identified as sacred, to maintain the sacred within the individual’s religious or spiritual experience, and finally to transform the sacred or modify it through the search process.

However, Hill et al. (2000) distinguished religion from spirituality with an important feature. Religion involves organised means and methods for the search for the sacred that are validated and supported by a community. Viewed as such, religion is composed of two elements: (1) the search for the sacred and (2) the group-validated means involved in the search. Spirituality only necessitates the first element. According to the authors, such a framework suggests that spirituality is an essential component of religion that can, and often does, occur within the context of religion. If this is the case, one can argue that it is not possible to refer to religion without a spiritual element. Thus, for further clarity, religion must be said to be composed of (1) a spiritual core and (2) participation in religious activities, or religious involvement. Having clarified this two-part conception of religion, it is clearer that one can refer to religion without a spiritual element. One could be religiously involved without actually experiencing spirituality. Similarly, spirituality can lead to people becoming part of a group with a prescribed doctrine, but it may also be experienced without any religious involvement. Therefore, an individual who is spiritual may not be religious at all in the organisational sense.

A study by Zinnbauer et al. (1997) examined a diverse range of sample populations ranging from ‘New Age’ groups to religiously conservative Christian college students. Amongst other tasks, participants were requested to rate how religious or spiritual they considered themselves to be on a 5-point Likert scale and also to choose one of four statements that best defined their own religiousness and spirituality: (1) I am spiritual and religious; (2) I am spiritual but not religious; (3) I am religious but not spiritual; and (4) I am neither spiritual nor religious. This study revealed that 74% of the subjects chose the first statement, 19% the second, 4% the third, and 3% the fourth. Another study by Woods and Ironson (1999) approached the subject in a similar manner, using semi-structured interviews to ask participants about their opinions on religion and spirituality. Forty-three percentage of the participants identified themselves as spiritual, 37% as religious, and 20% as both. Both of these studies showed the ability of the two constructs to coexist in a large group of individuals, at least as subjectively perceived by the individuals.

The above provides the basis for the present study, which aimed to categorise its participants into groups depending on their levels of religiosity and spirituality. However, instead of using the participants’ judgement of their levels of religiosity and spirituality, objective measures of these constructs were used. Participants were divided into the following groups: (1) a high level of religious involvement with a high level of spirituality, (2) a low level of religious involvement with a high level of spirituality, (3) a high level of religious involvement with a low level of spirituality, and (4) a low level of religious involvement with a low level of spirituality. The purpose was to compare the levels of psychological well-being between these 4 groups with the aim of revealing more about the relationship between religion and spirituality and psychological well-being. In addition, this study aims to examine the potential necessity of the spiritual core in the relationship.

Previous studies have attempted to understand the link between religion and psychological health (Pargament 1997; Pargament et al. 1998; Schumaker 1992). Schumaker’s (1992) extensive work compiles evidence of the role of religion in preventing depression, suicide, and fear of death, as well as in improving psychological well-being. Spirituality has also been shown to influence the process of recovery from chronic illnesses and to influence the course of medical and psychological interventions (Piedmont 2004). Of particular interest to researchers examining the link between religion/spirituality and well-being is how this influence is exercised. Various psychosocial factors that may mediate this link have been studied. These include the role of religion in providing social support and a sense of identity (Elliott and Hayward 2007) and the role of spirituality in providing a sense of meaning in life (Emmons 2005). Thus, religion and spirituality can be related to the concerns of the human spirit and the ways in which it can be developed to reach its fullest potential. This investigation aims to study the potential role of religion and spirituality in achieving this by linking them with 3 measures of psychological well-being: self-actualisation, meaning in life, and personal growth initiative.

Self-actualisation

As outlined by Abraham Maslow (1943, 1954), the hierarchy of needs was one of Maslow’s most enduring contributions to psychology (Koltko-Rivera 2006; Ivtzan 2009). According to Maslow, the self-actualising individual is at the top of this hierarchy, is more fully functioning, and lives a more enriched life than the average person (Shostrom 1964). Self-actualising individuals live in the present as opposed to the past or the future, function relatively autonomously, and tend to have a more benevolent outlook on life and human nature. A number of authors have contended that a self-actualising individual represents the goal of the psychotherapeutic process (Knapp 1990; Ivtzan and Conneely 2010).

Shostrom (1964) developed the Personal Orientation Inventory (POI), a measure of a person’s level of self-actualisation, as a direct correlate to the level of psychological health. A number of measures of religiosity have been found to be negatively related to scores on the Inner Support Scale of the POI that measures the tendency to be guided by one’s own principles and motives independent of external social constraints, but not simply out of rebelliousness (Tamney 1992). More recent studies (Tamney 1992) failed to find any anti-religious elements in a 15-statement short version of the POI, the Short Index of Self-Actualization (SISA; Jones and Crandall 1986). With regard to the link between spirituality and self-actualisation, Piedmont (2001) found a positive correlation between the Spiritual Transcendent Scale and the SISA. Similarly, Watson et al. (1990) revealed a significant correlation between religious beliefs about the self and the SISA scores.

In relation to religion and spirituality, and their interesting connection to self-actualisation, Tamney (1992) wrote that

In Maslow’s model, the healthy person is priest like, mystic like, and godlike. Maslow’s ideal person is not anti-spiritual. However, Maslow did believe that religions tend to affirm asceticism, self-denial, and the deliberate rejection of the needs of the organism, and that such a perspective would prevent self-actualization. Moreover, the description of the healthy person as godlike suggests the difficulty in reconciling Maslow’s philosophy and any religion based on belief in a transcendent deity (p. 133).

Maslow’s (1954) negative attitude towards religion is easily detected in his claims that self-actualisation and orthodox religion are irreconcilable and that ‘So-called sacred books are interpreted very frequently as setting norms for behaviour, but the scientist pays as little attention to these traditions as to any other’ (p. 113). Still, as Tamney (1992) points out, Maslow was not anti-spiritual; he was anti-religion, emphasising again the need to differentiate between the terms. It is therefore natural to deduce that Maslow’s negative position was aimed towards what this study defines as group 3: high levels of religiousness with low levels of spirituality. This claim is supported by Watson (1993), who stated that the approach Maslow adopted towards religion was related to the fact that self-actualised individuals hardly ever displayed traditional religious commitments. It is therefore important to test the possible association between self-actualisation and religiousness/spirituality by delineating the constructs of spirituality and religion.

Meaning in Life

Viktor Frankl (1965) defined the innate desire to give as much meaning as possible to one’s life and to actualise as many values as possible as the will-to-meaning. He believed that the will-to-meaning was an essential human motive. The definition of meaning in life ranges from ‘coherence in one’s life’ to ‘goal directedness or purposefulness’ to ‘the ontological significance of life from the point of view of the experiencing individual’ (Steger, et al. 2006 p. 80). Lent (2004) discussed meaning in life in relation to goals, defining them as consciously articulated, personally important objectives that individuals pursue in their daily lives. In the past couple of decades, much has been learned about how goals contribute to long-term levels of psychological well-being, and how they act as a deep and meaningful basis for people’s sense of continuity (Karoly 1999).

Emmons (2005) discussed the role of religious and spiritual goals in predicting psychological well-being. He argued that they are not all equal in contributing to well-being, although out of all the types of goals, those of a spiritual nature possess the unique ability to predict it. These meaningful goals are oriented towards the sacred and are concerned with ultimate purpose, meaning, commitment to a higher power, and seeking the divine in everyday life. It has indeed been found that the presence of theistic spiritual goals in particular is related to greater levels of goal integration that unite separate goal strivings into a coherent structure (Emmons et al. 1998). Emmons (2005) did not delineate religion and spirituality in discussing their different roles in providing a sense of meaning in life, but emphasised that religious and spiritual strivings seem to have the potential to establish goals and value systems that pertain to all aspects of a person’s life.

Personal Growth Initiative

Psychologists believe that it is highly desirable to be aware of one’s motives, personality patterns, and behaviour, as well as one’s ability to alter these in a positive light (Schumaker 1992). The term personal growth initiative describes active and intentional engagement in the process of personal growth psychotherapy aims to achieve for its clients (Robitschek 1998). The construct is based on the idea that continued personal growth throughout life is important for a healthy individual as they encounter new challenges, transitions, and experiences. The growth initiative has been associated with higher levels of psychological well-being (Robitschek and Kashubeck 1999) and lower levels of distress (for example depression and anxiety).

As stated earlier, in defining the constructs of religion and spirituality, Hill et al. (2000) argued that both involve a search for the sacred. They described ‘search’ as an attempt to identify, articulate, maintain, or transform. It can be inferred that as an individual performs these steps, he begins to break his boundaries and grow and by doing that, he is actively and willingly creating a process of change and therefore involving his personal growth initiative. As a manifestation of these ideas, Caldwell (2000) suggested that personal growth initiative might be a moderating factor influencing the change of attitude (negative or positive) an individual has towards religion and spirituality following a trauma. Ellens (2007) describes an inner spiritual pressure to cross a boundary, which ‘comes from new interior insights and new exterior stimuli’ (p. 69). Finally, Wink and Dillon (2003) found a positive association between spirituality and the personal growth aspects of well-being. They proposed that a tendency towards personal growth leads to highly spiritual individuals who provide role models to those around them.

Hypotheses

Measures of religious involvement and spirituality were used to divide participants into 4 groups: (1) high religious involvement and high spirituality (R+S+), (2) low religious involvement and high spirituality (R−S+), (3) high religious involvement and low spirituality (R+S−), and (4) low religious involvement and low spirituality (R−S−).

It was hypothesised that groups exhibiting a higher level of spirituality are likely to exhibit higher levels of psychological well-being, whether or not experienced within the context of religious activity; therefore, groups (1) and (2) would provide higher scores on all three dependent variables of psychological well-being (self-actualisation, meaning in life, and personal growth initiative) in comparison with groups (3) and (4).

Method

Participants

A total of 205 participants took part consisting of attendees of London’s various religious institutions, meetings, and spiritual groups. The sample was made up of 114 men (55.6%) and 91 women (44.4%), whose ages ranged from 21 to 76 with a mean age of 41.12 years (SD = 13.29). The religious affiliations of the participants were 32.2% Christian, 17.6% Muslim, 14.6% Quaker, 10.2% Jewish, 9.3% Buddhist, and 16.1% ‘none’.

Measures

Religious Involvement

In order to measure participants’ extent of participation in religious activity, a 5-item index of organisational religiosity was used (Fry 2000) and items were rated on a scale of 1 (not at all) to 6 (very much). For example, item 2 measured the frequency of attending church, synagogue, mosque, or any other formal place of worship; item 4 measured participants’ involvement in diverse forms of informal religious activity such as religious services, listening to or watching talk shows on TV and radio, hymn singing, church music or bible reading. This measure was used by Fry (2000) in studying religious involvement and well-being in a manner that enabled spirituality to be measured separately to religious involvement.

Spiritual Transcendence Scale

The Spiritual Transcendence Scale (STS) was developed by Piedmont (1999; 2001) and is a 24-item scale with three sub-scales: Universality, Prayer Fulfilment, and Connectedness, each with eight items. It employs a Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. Scores on these scales have been shown to predict a variety of related spiritual constructs (Piedmont 2004). Piedmont and Leach (2002) have also shown that the STS generalised cross-culturally to an Indian sample of Muslims, Christians, and Hindus, as well as to a large sample of Filipino Christians when translated into their native language (Piedmont 2007).

Short Index of Self-Actualization

Self-actualisation was measured by the Short Index of Self-Actualization (SISA), which was developed by Jones and Crandall (1986). The SISA consists of 15 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale again ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The SISA was a modification of the most widely accepted measure of self-actualisation—the Personal Orientation Inventory (POI; Shostrom 1964). The index significantly correlated with this inventory and also had a significant correlation in expected directions of self-esteem and neuroticism, susceptibility of boredom, perfectionism, and creativity (Prosnick 1999).

Meaning in Life Questionnaire

The Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ) was developed by Steger et al. (2006) to assess 2 dimensions of meaning in life—the Presence of Meaning (MLQ-P) and the Search for Meaning (MLQ-S)—using 10 items rated on a 7-point scale from 1 (absolutely untrue) to 7 (absolutely true). Within this investigation, we were not interested in the search for meaning, but more in the actual presence of meaning in the participants’ lives (to be able to distinguish levels of meanings’ prevalence in the different groups); therefore, the MLQ-P measurement was used. The MLQ-P subscale measures how full of meaning participants feel their lives are. It has a positive correlation with well-being, intrinsic religiosity, extraversion, and agreeableness, and a negative correlation with anxiety and depression. MLQ-P scores have also been shown to be related to, but distinct from, life satisfaction, optimism, and self-esteem (Steger and Frazier 2005).

Personal Growth Initiative Scale

The Personal Growth Initiative Scale (PGIS) is a self-report instrument that measures personal growth initiative. It was developed by Robitschek (1998) and consists of 9 items that are rated on a 6-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Within primarily European American samples, data suggest that the PGIS is positively related to psychological well-being, internal locus of control, and assertiveness, and negatively related to psychological distress.

Procedure

The researcher distributed questionnaires to attendees of worship services at religious centres such as the church, mosque, synagogue, Quaker meeting house, religious student meetings at the university, spiritual group meetings, and lectures on spirituality-related topics. Those who were willing to participate either returned the completed questionnaires directly or were given a stamped addressed envelope in which they could return them after they had been completed.

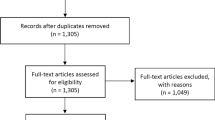

Data Analysis

A mean score was determined from the scores for religious involvement and STS, and the participants were divided into four groups on this basis. Participants who scored ‘highly’ in each measure had overall scores above the mean, while those who scored ‘low’ had results below the mean. A one-way between-subject analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to investigate differences in levels of well-being between the four groups. This procedure was used to compare the total scores on each of the 3 measures of psychological well-being (SISA, MLQ-P, and PGIS). A post hoc test was then used to analyse the difference between each group for each of the measures of well-being, in order to determine whether levels were significantly different between groups.

Results

Correlation Analyses

Simple correlations were run between each DV and the predictors (religiosity and spirituality) before embarking on the ANOVA analysis. As shown in Table 1, these suggest that, as hypothesised, there is no evidence of a significant linear relationship between religiosity and the 3 measures of well-being, whereas spirituality is positively related to all 3 dependent variables. The lack of a correlation between spirituality and religiosity strengthens the assumption that the two concepts are distinct from one another.

The mean score for the measure of religious involvement was 19.30 (SD = 6.99); participants scoring above this score were categorised as ‘high’ in their religious involvement, while those who had a score below 19.30 were classified ‘low’. The mean score for the measure of STS was 90.99 (SD = 13.58); participants scoring above this score were defined as ‘high’ in their spirituality, and those with a score below 19.30, ‘low’. This allowed the establishment of 4 groups: (1) (R+S+), (2) (R−S+), (3) (R+S−), and (4) (R−S−).

Comparison of Levels of Psychological Well-being Between the Groups

Using a one-way ANOVA to compare the means, significant differences were found between the four groups in all 3 measures of well-being:

-

Scores on the SISA: F = 8.24, df = 3, P < 0.000;

-

Scores on the MLQ-P: F = 9.71, df = 3, P < 0.000;

-

Scores on the PGIS: F = 11.70, df = 3, P < 0.000.

Post hoc tests yielded results as shown in Table 2.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine whether differences in several predictors of well-being would be found between groups with differing levels of religious involvement and spirituality. The results indicate that these differences were present in each measure of well-being tested, which has potentially important implications.

In relation to SISA scores, group (3) scored significantly lower than groups (1) and (2), which corresponds to Tamney’s discovery (1992) that religion correlates negatively with the POI. Tamney suggested that this association could in part be due to the cultivation of dogmatism among the adherents of religious institutions. In other words, he implies that the lowest self-actualisers were those who were highly religiously involved with little experience of spirituality. It is interesting to note that the difference between groups (1) and (4) and groups (2) and (4) was not statistically significant. The meaning of this is that those who carry no connection to religion/spirituality exhibit higher levels of self-actualisation (and the self-fulfilling aspects of it) than those who are religious without spirituality. Fuller (1988) describes this as one of the earliest stages of religiosity, shaped by imitation and identification with others, mechanistic righteousness to ‘placate’ a projection of God. These behaviours can lead to psychopathology (p. 47, Ellens 2007). Therefore, Maslow’s (1954) negative attitude towards religion was justified, but only when religion is discussed in the narrowest way, on the level of activity, when deprived of its spiritual aspects. Such data also strengthen the results and ideas presented in Piedmont (2001), which links self-actualisation and spirituality. Similar understandings can be derived concerning the parameter of meaning in life.

As with the SISA scores, MLP-Q was found to be significantly lower in group (3) when compared with groups (1) and (2); such significantly lower scores were not found when groups (1) and (2) were compared with group 4. Again, the implication of this result is that, when compared with spiritual individuals (with or without a religious context), participants who were religious with no spirituality to accompany this practice showed significantly lower levels of meaning in their lives. As declared by Emmons et al. (1998), spiritual striving has been linked with goal integration and meaning; these results support such claims and hone Emmons’ (2005) descriptions. While Emmons (2005) did not delineate religion and spirituality (in the course of establishing their importance in creating goals and meaningful value systems), these results imply that we need to distinguish between the two. Practicing religion in the context of spirituality (as with practicing spirituality by itself) deepens the levels of meaning in one’s life, while practicing religion without spirituality does the opposite. In connection with these results, it is important to consider Chamberlain and Zika (1992) who discussed the way religion provides meaning in our lives. Their findings indicate that although religion may provide an important source of meaning, for most people, meaning is a product of creation and individuals must find it and construct their own sense of order themselves. Therefore, one cannot be provided with meaning in life; rather, one must conceive it themselves, as with the search for the sacred. A self-perpetuated search leads to many positive cognitive and emotional experiences, including security, peace, clarity and purpose, unity, and strength (Ellens 2008). Such a personal creation of deeper realisations might be explored by those who incorporate spirituality in their practice of religion. This personal process might be absent for those who practice religion without spirituality, thereby leading them to lower levels of meaning in life.

Scores on the PGIS demonstrated similar trends to those observed on the SIAS and the MLQ-P. Differences on this measure were significant between groups (1) and (3) and groups (1) and (4), but not between groups (2) and (3) or groups (2) and (4). This indicates that personal growth initiative is highest when one is highly religiously involved and highly spiritual compared with individuals who are low in both or high in religion and low in spirituality; mere religious participation without the spiritual dimension does not stir much personal growth initiative. The search for the sacred, as described by Hill et al. (2000), is illustrated by the results as being moderated by spirituality as individuals who find higher levels of spirituality (with or without religion) carry higher levels of personal growth initiative. These results also bring us back to Chamberlain and Zika (1992) and their creation of meaning. It is quite clear that individuals with higher levels of personal growth initiative tend to explore, seek, meld, and create their personal meaning. This is an active process that has been found in these data to be highly related to spirituality and the personal search it entails. Another interesting point concerning the PGIS is that no difference was found between groups (2) and (3) or (4). This indicates an advantage for the environment that entails both religion and spirituality in comparison with only spirituality. It might be that spirituality without any context, without religious background, is less effective in supporting the personal growth initiative. The combination of a given structure for seeking the individual (religion) while looking for personal interpretation for such work (spirituality) provides the most fertile ground for the individual to promote levels of growth initiative.

Similar understandings could be derived from the simple correlations that point to a number of interesting implications. No significant relationship was found between the religiosity and the 3 measures of well-being, while spirituality has been found to be positively related to all 3 dependent variables. Another important finding is the lack of correlation between spirituality and religiosity. These data are in line with this study’s ANOVA results and former studies estimating that the parameters of spirituality and religiosity are indeed essentially different. This is the case as long as we remember to accurately measure these two variables. Spirituality should focus on the search for the sacred, while religiosity should focus on religious activities; when that happens, we find two distinct measurements that allow better prediction and control over their impact on psychological well-being.

It has been proposed by a number of researchers (e.g., Cohen and Koenig (2003); Schumaker 1992) that religiosity/spirituality are positively related to well-being. At the same time, religion and spirituality are not clearly defined (Hill et al. 2000), and therefore, the scientific research of their relationship is not clear or without fault. As suggested by Miller and Thoresen (2003), the investigation of spirituality and religion in relation to health and well-being is an important frontier for psychology, which also attracts high public interest. Our greatest task is the delineation of these two concepts as we move towards greater understanding concerning the specific circumstances under which they influence well-being. It is also crucial for us to learn more about the relationship between the two; if indeed they are different, in what way are they influencing well-being separately in comparison with being combined? As we learn, the importance of religion and spirituality in our lives future research is obligated to answering these questions. This paper contributes to this task by emphasising the theoretical and methodological differences and connections between religion and spirituality, the unique operationalism of each, and their relationship to 3 important aspects of psychological well-being.

Conclusions

The above findings are important in the context of the increasing volume of studies debating concepts of religion and spirituality. They support the fact that these concepts are truly differentiated. Positive psychological aspects of well-being were found to be significantly different for groups carrying different levels of religious involvement and spirituality. Individuals with higher levels of spirituality (with or without religion) showed higher levels of self-actualisation and meaning in life, while higher levels of personal growth initiative were only found for the group combining high levels of religiosity with spirituality. The main characteristic differentiating the groups was the core of spiritual practice—the personal experience of the transcendent. Having become aware of the benefits of spirituality on psychological well-being, it is important to promote this. Religious involvement without a spiritual element could be termed empty religion, in which the salutary benefits of well-being have not been observed. Formally structured religion, with prescribed theology and rituals, which does not carry a subjective seeking or personal experience, holds much less benefit for the individual. In other words, spirituality is emphasised as a mediating variable between religious activity and psychological well-being. Realising this, people may be more inclined to incorporate spirituality into their lives to actively look for a personal interpretation of their experience.

References

Argyle, M., & Beit-Hallahmi, B. (1975). The social psychology of religion. London and Boston: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Caldwell, J. K. (2000). A model of trauma with spirituality and religiosity: The mediating and moderating effects of personal growth initiative and openness to experience (Doctoral dissertation). Texas: Texas Tech University.

Chamberlain, K., & Zika, S. (1992). Religiosity, meaning in life, and psychological wellbeing. In J. F. Schumaker (Ed.), Religion and mental health (pp. 138–148). New York: Oxford University Press.

Cohen, A. B., & Koenig, H. G. (2003). Religion, religiosity and spirituality in the biopsychosocial model of health and ageing. Ageing International, 28, 215–241.

Dollahite, D. C. (1998). Fathering, faith and spirituality. Journal of Men’s Study, 7, 3–15.

Ellens, J. H. (2007). Radical grace: How belief in a benevolent God benefits our health. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger.

Ellens, J. H. (2008). Understanding religious experiences: what the Bible says about spirituality. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger.

Elliott, M., & Hayward, R. D. (2007). Religion and the search for meaning in life. Journal of Counselling Psychology, 53, 80–93.

Emmons, R. A. (2005). Striving for the sacred: personal goals, life meaning, and religion. Journal of Social Issues, 61, 731–745.

Emmons, R. A., Cheung, C., & Tehrani, K. (1998). Assessing spirituality through personal goals: implications for research on religion and subjective well-being. Social Indicators Research, 45, 391–422.

Frankl, V. E. (1965). The doctor and the soul: From psychotherapy to logotherapy. Great Britain: Penguin Books Ltd.

Fry, P. S. (2000). Religious involvement, spirituality and personal meaning for life: Existential predictors of psychological wellbeing in community-residing and Institutional care elders. Aging and Mental Health, 4, 375–387.

Fuller, R. C. (1988). Religion and the life cycle. Philadelphia: Fortress.

Greenway, A. P., Meagan, P., Turnbull, S., & Milne, L. C. (2007). Religious coping strategies and spiritual transcendence. Mental Health, Religion and Culture, 10, 325–333.

Hill, P. C., & Pargament, K. I. (2003). Advances in the conceptualization and measurement of religion and spirituality: Implications for physical and mental health research. American Psychologist, 58, 64–74.

Hill, P. C., Pargament, K., Hood, R. W., McCullough, M. E., Swyers, J. P., Larson, D. B., et al. (2000). Conceptualizing religion and spirituality: Points of commonality, points of departure. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 30, 51–77.

Ivtzan, I. (2009). Self actualisation: For individualistic cultures only? International Journal on Humanistic Ideology, 1(2), 111–138.

Ivtzan, I., & Conneely, R. (2010). Androgyny in the mirror of self-actualisation and spiritual health. The Open Psychology Journal, 2, 58–70.

James, W. (1902). The varieties of religious experience. London: Routledge.

Jones, A., & Crandall, R. (1986). Validation of a short index of self-actualization. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 12, 63–73.

Karoly, P. (1999). A goal systems–Self-regulatory perspective on personality, psychopathology, and change. Review of General Psychology, 3, 264–291.

Knapp, R. R. (1990). Handbook for the personal orientation inventory. San Diego, Calif: Edits Publishers.

Koltko-Rivera, M. E. (2006). Rediscovering the later version of Maslow’s Hierarchy of needs: Self-transcendence and opportunities for theory, research, and unification. Review of General Psychology, 10, 302–317.

Lent, R. W. (2004). Toward a unifying theoretical and practical perspective on well-being and psychosocial adjustment. Journal of Counselling Psychology, 51, 482–509.

MacDonald, D. A. (2000). Spirituality: Description, measurement and relation to the five factor model of personality. Journal of Personality, 68, 153–197.

MacDonald, D. A., & Holland, D. (2003). Spirituality and the MMPI-2. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 59, 399–410.

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50, 370–396.

Maslow, A. H. (1954). Motivation and personality. New York: Harper.

McGrath, A. E. (1999). Christian spirituality: an introduction. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

Miller, W. R., & Thoresen, C. E. (2003). Spirituality, religion, and health: An emerging research field. American Psychologist, 58, 24–35.

Moreira-Almeida, A., Neto, F. L., & Koenig, H. G. (2006). Religiousness and mental health: A review. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 28, 242–250.

Paden, W. E. (2005). Comparative religion. In J. R. Hinnells (Ed.), The Routledge companion to the study of religion (pp. 208–226). London: Routledge.

Paloutzian, R. F., & Park, C. L. (Eds.) (2005). Handbook of the psychology of religion and spirituality. New York: Guilford Press.

Pargament, K. I. (1997). The psychology of religion and coping. New York: Guilford Press.

Pargament, K. I., Koenig, H. G., Tarakeshwar, N., & Hahn, J. (2001). Religious struggle as a predictor of mortality among medically ill elderly patients: A 2-year longitudinal study. Archives of Internal Medicine, 161, 1881–1885.

Pargament, K. I., Smith, B. W., Koenig, H. G., & Perez, L. (1998). Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 37, 710–724.

Piedmont, R. L. (1999). Does spirituality represent the sixth factor of personality? spiritual transcendence and the five-factor model. Journal of Personality, 67, 985–1013.

Piedmont, R. L. (2001). Spiritual transcendence and the scientific study of spirituality. Journal of Rehabilitation, 6, 4–14.

Piedmont, R. L. (2004). Spiritual transcendence as a predictor of psychosocial outcome from an outpatient substance abuse program. Psychology of Addictive Behaviours, 18, 213–222.

Piedmont, R. L. (2007). Cross-cultural generalizability of the spiritual transcendence scale to the philippines: Spirituality as a human universal. Mental Health, Religion and Culture, 10, 89–107.

Piedmont, R. L., & Leach, M. M. (2002). Cross-cultural generalizability of the spiritual transcendence scale in India:spirituality as a universal aspect of human experience. American Behavioral Scientist, 45, 1888–1901.

Prosnick, K. P. (1999). Claims of near-death experiences, gestalt resistance processes, and measures of optimal functioning. Journal of Near-Death Studies, 18, 27–34.

Robitschek, C. (1998). Personal growth initiative: The construct and its measure. Measurement and Evaluation in Counselling and Development, 30, 183–198.

Robitschek, C., & Kashubeck, S. (1999). A structural model of parental alcoholism, family functioning and psychological health: the mediating effects of hardiness and personal growth orientation. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 46, 159–172.

Rollins, W. G. (1999). Soul and psyche, the bible in psychological perspective. Minneapolis: Fortress Press.

Schumaker, J. F. (1992). Religion and mental health. New York: Oxford University Press.

Seidlitz, L., Abernethy, A. D., Duberstein, P. R., Evinger, J. S., Chang, T. H., & Lewis, B. (2002). Development of the spiritual transcendence index. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 41, 439–453.

Sheldrake, P. (2007). A brief history of spirituality. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Shostrom, E. L. (1964). An inventory for the measurement of self-actualization. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 24, 207–218.

Steger, M. F., & Frazier, P. (2005). Meaning in life: One link in the chain from religiousness to well-being. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52, 574–582.

Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S., & Kaler, M. (2006). The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53, 80–93.

Tamney, J. B. (1992). Religion and self-actualization. In J. F. Schumaker (Ed.), Religion and mental health (pp. 132–137). New York: Oxford University Press.

Tart, C. T. (1975). Introduction. In C. T. Tart (Ed.), Transpersonal psychologies (pp. 3–7). New York: Harper and Row.

Trenholm, P., Trent, J., & Compton, W. C. (1998). Negative religious conflict as a predictor of panic disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 54, 59–65.

Vaughan, F. (1991). Spiritual issues in psychotherapy. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 23, 105–119.

Watson, P. J. (1993). Apologetics and ethnocentrism: Psychology and religion within an ideological surround. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 3(1), 1–20.

Watson, P. J., Morris, R. J., & Hood, R. W., Jr. (1990). Intrinsicness, self-actualization, and the ideological surround. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 18, 40–53.

Williams, D. R., & Sternthal, M. J. (2007). Spirituality, religion and health: evidence and research directions. Medical Journal of Australia, 186, S47–S50.

Wink, P., & Dillon, M. (2003). Religiousness, spirituality, and psychosocial functioning in late adulthood: Findings from a longitudinal study. Psychology and Aging, 18, 916–924.

Woods, T. E., & Ironson, G. H. (1999). Religion and spirituality in the face of illness: How cancer, cardiac, and HIV patients describe their spirituality/religiosity. Journal of Health Psychology, 4, 393–412.

Zinnbauer, B. J., & Pargament, K. I. (2005). Religiousness and spirituality. In R. F. Paloutzian & C. L. Park (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of religion and spirituality (pp. 21–42). New York: Guilford Press.

Zinnbauer, B., Pargament, K. I., Cowell, B., et al. (1997). Religion and spirituality: Unfuzzying the fuzzy. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 36, 549–564.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ivtzan, I., Chan, C.P.L., Gardner, H.E. et al. Linking Religion and Spirituality with Psychological Well-being: Examining Self-actualisation, Meaning in Life, and Personal Growth Initiative. J Relig Health 52, 915–929 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-011-9540-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-011-9540-2