Abstract

Cultural issues impact on health care, including individuals’ health care behaviours and beliefs. Hasidic Jews, with their strict religious observance, emphasis on kabbalah, cultural insularity and spiritual leader, their Rebbe, comprise a distinct cultural group. The reviewed studies reveal that Hasidic Jews may seek spiritual healing and incorporate religion in their explanatory models of illness; illness attracts stigma; psychiatric patients’ symptomatology may have religious content; social and cultural factors may challenge health care delivery. The extant research has implications for clinical practice. However, many studies exhibited methodological shortcomings with authors providing incomplete analyses of the extent to which findings are authentically Hasidic. High-quality research is required to better inform the provision of culturally competent care to Hasidic patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cultural issues impact on the health and well-being of individuals, on their health care behaviours and beliefs, and on their experiences of health care. The impact of cultural issues is observed in almost all aspects of health care, including awareness of and attitude to lifestyle risk factors for disease, awareness of early signs and symptoms of disease, access to and uptake of prevention, screening, diagnostic and treatment services, and access to and uptake of information and support services (US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health 2001). Definitions of what constitutes a specific disease vary according to the cultural context (Dein 2006), as do explanatory models of illness (Kirmayer 2004). An individual’s experience of illness cannot be considered in isolation from the cultural context in which it occurs.

Initiatives to make health care services more responsive to the individual needs of patients through the provision of culturally sensitive and appropriate services are widespread across clinical conditions and health care settings (Department of Health 2007; Commission for Social Care Inspection 2008; US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health 2001). Health care practitioners are urged to achieve ‘cultural competency’ to better enable the provision of respectful and effective care that is compatible with the individual patient’s cultural health beliefs and practices and preferred language. This includes striving to overcome cultural, language and communications barriers; providing an environment in which patients from diverse cultural backgrounds feel comfortable discussing their cultural health beliefs and practices when negotiating treatment options; encouraging patients to express their spiritual beliefs and cultural practices; and being familiar with and respectful of various traditional healing systems and beliefs and, where appropriate, integrating these into treatment plans (US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health 2001). Research investigating the health care behaviours and beliefs of individuals from diverse cultural backgrounds has a vital role to play in assisting health care professionals, understanding the patients they encounter, and better enabling them to provide culturally competent care that addresses the totality of the patient’s needs surrounding their illness. High-quality systematic reviews are of particular value in this endeavour.

As part of an ethnographic study exploring health care behaviours and beliefs concerning cancer in a population of Satmar Hasidic Jews living in London, we conducted a systematic review of the literature exploring health care behaviours and beliefs in Hasidic Jewish populations, a religious and cultural group that is under-researched and in respect of whom no systematic literature review had been conducted. This paper presents the findings of the review.

Hasidism: A Primer

Hasidism was founded in the second half of the eighteenth century by Rabbi Yisrael ben Eliezer (1698–1750), known as the Baal Shem Tov (literally, Master of the Good Name). One of the many Jewish ‘miracle workers’, he used kabbalah to provide people with practical assistance. Initially centred in Eastern Poland, the movement grew to influence the majority of Jewish communities throughout Central and Eastern Europe.

Religious divisions within Judaism can be understood by reference to a spectrum of outlook ranging from the secular to the strictly orthodox, which is measurable according to two criteria: the extent to which adherents view religious laws as God-given and immutable, and the attitude adherents take to the secular world. Hasidic Jews are at the strictly orthodox end of this spectrum. Central to their belief and practice is the Halacha (literally, the way), the corpus of Jewish law regulating all aspects of behaviour for Orthodox Jews. Hasidic Jews believe that the Halacha is of Divine origin and its observance is obligatory. Matters covered include religious ritual, tort and ethics, and medical Halacha is a continually developing area. Rabbinic authorities establish and maintain guidelines for behaviour, issuing public statements and personal responsa. Strict religious obligation includes observance of the Sabbath, festivals and dietary laws, modesty in behaviour and dress, separation of men and women in public domains, and, for men, ongoing religious study and thrice daily prayer. Many features of the secular world are perceived as detracting from God’s sanctity, and Hasidic Jews live in tightly knit communities functioning in self-imposed cultural insularity.

These aspects of Hasidic theology and practice are common to other strictly orthodox groups, collectively known as haredim (literally, those who tremble [in the presence of God]). Other aspects differentiate Hasidim considerably from non-Hasidic haredim. The most significant distinction is the Doctrine of the Zaddik (literally, righteous one), the belief that the individual Jew should affiliate with a living representative of the Divine world. A Zaddik, latterly known as a Rebbe, assumes responsibility for the well-being of his followers by ascending spiritually to the Divine realms bringing the flow of Divine grace to the temporal world. Other distinctions include the emphasis on religious ecstasy and mystical fervour, and the prominence of kabbalistic texts and practices. Traditionally, Hasidim have sought their Rebbe’s advice and assistance during illness: in his role as spiritual leader, a Rebbe is in a unique position to provide religious understandings of suffering.

Over time, the number of Hasidic Courts grew: different Rebbes emphasised different aspects of Hasidic practice and belief, becoming renowned for different qualities. The characteristics of Hasidic Courts are determined largely by the personalities and concerns of their Rebbes. Hasidim are not homogeneous, with groups exhibiting differences in theology, practice, and in their relationship to the outside world. For example, Lubavitch Hasidism places a strong emphasis on outreach work, attempting to bring less religiously observant Jews to greater religious practice. Most other Hasidic groups are unconcerned with this. Outreach means that Lubavitch is less culturally isolated than other Hasidic groups. By contrast, Toldos Aharon maintains an unbending degree of cultural insularity, even preferring not to associate with Hasidim from groups they consider to have a lower level of observance than their own. See further Dan (1998), Mintz (1994), Wertheim (1992).

Methods

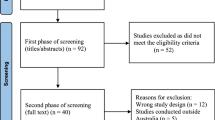

Several methods were used to identify relevant research articles. Firstly, we searched the databases AMED, CINAHL Plus, EMBASE, OVID MEDLINE (R) and PsycINFO individually from the earliest to the most recent issue relative to the search date (April week 4 2010) using each of the following keywords and phrases: (C)has(s)idic, (c)haredi, ultraorthodox Jew(ish), and orthodox Jew(ish). Secondly, references of papers identified were retrieved, as were references of references. Thirdly, authors of identified papers were asked whether they knew of published or unpublished research. Finally, experts in the field were asked whether they knew of research. An initial assessment of suitability for inclusion was conducted by reading the abstracts of all papers identified. These initial stages of paper identification indicated a dearth of research in this area, and we decided that papers incorporating a range of methodologies including quantitative and qualitative and case series and case reports would be eligible for inclusion. We also decided to include reports on both medical and mental health issues. Epidemiological reports were excluded as were papers describing optimum practice or providing professional guidance. During the early stages of article identification, papers remained eligible for inclusion if they reported on an empirical investigation into health care behaviours or beliefs in a Hasidic, haredi, ultraorthodox or orthodox Jewish sample. Where the sample was described as haredi, ultraorthodox or orthodox Jewish, the authors were asked whether participants were known to have been Hasidic. Where all or some were, the paper was included. Where only some were Hasidic, authors were asked whether and how results differed for the Hasidic subgroup. Where the sample was defined as Hasidic, the authors were asked whether participants belonged to a particular Hasidic Court.

We identified 21 studies reported in 25 papers for inclusion. This relatively small set of studies was heterogeneous in many respects and hence unsuitable for quantitative analysis (e.g. meta-analysis). Instead, they were evaluated qualitatively.

Results and Discussion

Methodological Overview

Twenty-one studies reported in 25 papers on empirical investigations into health care behaviours or beliefs in a sample including at least some Hasidic Jews. Nine studies examined medical issues including use of religious healing (Dein 2002, 2004a, b; Littlewood and Dein 1995), awareness of osteoporosis (Goddard and Helmreich 2004), experiences of cancer (Mark and Roberts 1994), genetic carrier screening (Raz and Vizner 2008), knowledge about menstruation (Zalcberg 2009), mothers’ experiences of their children’s autism (Shaked 2005; Shaked and Bilu 2006), and provision of health care services (Erez et al. 1999; Law and Wallfish 1991; Stein-Zamir et al. 2008). The remaining 12 studies investigated mental health issues including psychiatric referral letters sent by Rabbis (Goodman and Witztum 2002), hypersexualised behaviour of psychiatric inpatients (Needell and Markowitz 2004), patients’ explanatory models of mental illness (Rosen et al. 2008), involvement of religious and cultural attitudes in psychogenic menstrual disorders (Sheinfeld et al. 2007) and in obsessive–compulsive symptoms concerning menstruation (Vishne et al. 2008), and presentation, assessment and treatment of mental health patients (Feinberg 2005; Goodman 2009; Littlewood 1983; Paradis et al. 1996; Schechter et al. 2008; Trappler et al. 1995; Witztum et al. 1990).

The majority of studies were qualitative (N = 17), 11 of which were case studies or case series. Samples were exclusively Hasidic in 13 studies (Dein 2002, 2004a, b; Erez et al. 1999; Feinberg 2005; Goddard and Helmreich 2004; Law and Wallfish 1991; Littlewood 1983; Littlewood and Dein 1995; Mark and Roberts 1994; Needell and Markowitz 2004; Sheinfeld et al. 2007; Stein-Zamir et al. 2008; Trappler et al. 1995; Witztum et al. 1990; Zalcberg 2009). Seven of these included the members of a single Hasidic group, namely Lubavitch (Dein 2002, 2004a, b; Erez et al. 1999; Littlewood and Dein 1995; Trappler et al. 1995), Bratslav (Stein-Zamir et al. 2008; Witztum et al. 1990), Satmar (Littlewood 1983), and Toldos Aharon (Zalcberg 2009). In only five studies do authors provide any details of their recruitment methods and the criteria used to determine Hasidic status. In only one of these, where status was determined by self-assignment via self-completion semistructured questionnaire, are these methods transparent and adequate (Rosen et al. 2008). As might be expected, the majority of studies took place in Israel (N = 11), with the remainder taking place in America (N = 7), mostly in New York, and in London (N = 3).

The extent to which authors consider what makes their participants’ beliefs and behaviours authentically Hasidic varies considerably, although the majority pay little attention to this. For example, Goddard and Helmreich (2004) provide a cultural and sociological explanation for their findings concerning Hasidic women’s awareness of osteoporosis, emphasising that participants’ beliefs and behaviours stem from cultural insularity. However, by largely omitting to consider Hasidic theology and by focussing on phenomena that are also characteristic of non-Hasidic haredim, the authors are unable to capture what makes their participants’ behaviour uniquely Hasidic. By contrast, Dein (2002, 2004a, b) and Littlewood and Dein (1995), who studied Lubavitch Hasidim, and Goodman and Witztum (2002), and Witztum et al. (1990), who each focussed on Bratslav Hasidim, provide in-depth analyses that more fully reflect the Hasidic characteristics of their respective populations. By focussing on a single Hasidic group, these authors are able to discuss their findings in extremely specific terms, invoking Lubavitch and Bratslav theologies to demonstrate what makes their findings not only authentically Hasidic but authentically Lubavitch or Bratslav as well.

In addition to drawing on Hasidic sociological, cultural and theological phenomena, in order to demonstrate the extent to which and the ways in which their findings are authentically Hasidic, authors need to contextualise their findings against the background of relevant research conducted in other populations. Contextualising in this way enables authors to identify whether observed behaviour or expressed beliefs are shared by other populations or unique to Hasidim. Generally, authors do not consider such research: the study by Zalcberg (2009) investigating how Toldos Aharon girls obtain information concerning menstruation is an exception. Her analyses that take into consideration related research in other populations lead her to conclude that although Toldos Aharon adopts an extreme position in their management of information concerning menstruation, their behaviour and beliefs are part of a continuum and reflect a difference of degree not of kind.

Studies are subject to other methodological inadequacies: in particular, power calculations (where relevant) are wholly absent, and generally, both for quantitative and for qualitative studies, authors do not state whether their sample sizes are adequate to the study design. Additionally, in four studies, authors provide inadequate details concerning their methods of data collection (Goddard and Helmreich 2004; Mark and Roberts 1994), including whether investigator-developed measurement tools tested satisfactorily for reliability and validity (Law and Wallfish 1991; Rosen et al. 2008).

Study Findings

Although the reviewed studies are diverse in subject matter, methods, level of analysis and quality, making it difficult to draw overall conclusions concerning the health care behaviours and beliefs of Hasidic Jews, several themes emerge:

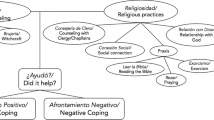

Spiritual Healing

Two studies investigated Hasidic patients’ recourse to spiritual healing. Dein (2002, 2004a, b) and Littlewood and Dein (1995) report on anthropological fieldwork conducted in a Lubabvitch community.Footnote 1 In more serious illnesses or when medical advice was deemed ‘simplistic’, Lubavitchers contacted their Rebbe for a cure and a religious explanation for their illness.Footnote 2 Lubavitch philosophy asserts that Hebrew created and sustains the world: words are not merely representational, everything, including the human body, is reducible to language. The Rebbe’s responses, including instructions that individuals check their ritual texts reflected this. Other religious practices might also be prescribed, including ensuring with increased vigilance that only strictly kosher food was eaten. According to Lubavitch theology, the spiritual and temporal worlds are causally connected. Respondents drew upon this, asserting that the Rebbe could cure illnesses by ascertaining which spiritual issues required correction in order to produce the improvement in physical health. Individuals typically reported that his instructions revealed areas of religious observance where they had unwittingly been lax: following them resulted in a cure. These findings are echoed by Shaked (2005) and Shaked and Bilu (2006) who found that mothers sought spiritual healing for their autistic children. This included blessings, recitation of religious texts, amulets and exorcism. Interestingly, the authors report that although greater use was made of medical and educational therapies, mothers tended to attribute improvements in their children’s condition to spiritual interventions.

Use of Religious Explanatory Models

Hasidim may incorporate religion in their explanatory models of illness. A case series of 19 male Bratslav psychiatric patients demonstrates how explanatory models of and attitudes towards mental illness reflect the teachings and experiences of the group’s founder, Rebbe Nahman (Witztum et al. 1990).Footnote 3 Experiencing alternating euphoria and dysphoria, Rebbe Nahman undertook mystical quests in his struggles over faith during which he explored the meaning of his depression. A theory emerged where the dividing line between the pathological and the holy is thin: in some circumstances, behaviour indicates mental illness, yet in others it signifies great holiness. In keeping with this, modern-day Bratslav tolerates behaviour that elsewhere would be labelled bizarre. Solitary prayer, often in caves or the middle of forests, is normal as are nocturnal pilgrimages to the tombs of mystics. Rational thought is deemed suspect and, reflecting the unsuccessful treatment of Rebbe Nahman’s debilitating tuberculosis, doctors are to be avoided. The authors draw parallels between Rebbe Nahman’s experiences and the patients’ symptoms. Most were converts to Bratslav and had embraced a framework that accommodated and even valued many of their symptoms. Exhibiting paranoia with messianic content, patients withdrew into a psychotic world of demons and angels populating the mystical texts studied by Hasidim Bratslav. Nevertheless, the group deemed their behaviour pathological due to the marked change in their usual behaviours, self-neglect, overwhelming emphasis on fringe religious practice and a dramatic inversion where instead of being in control of their spirituality, it terrified them.

The analysis of referral letters sent to a psychiatric clinic by Bratslav Rabbis in respect of yeshiva students also demonstrates how theological beliefs inform attitudes towards mental illness (Goodman and Witztum 2002). The authors make the important point that a patient’s explanatory model may be rejected by others in their community. Hence, Rabbis delegitimised students’ accounts of their distress that focussed on mystical explanations, prioritising behavioural and social explanations instead. As before, notwithstanding Bratslav attitudes towards the potential holiness of mental distress, these students’ behaviour was considered pathological, not holy.

In one of the few studies presenting results separately for Hasidic and non-Hasidic participants, Rosen et al. (2008) found a disparity between Hasidic and non-Hasidic haredi psychiatric outpatients in respect of their explanations for their illness. Whilst half of the Hasidim gave religious explanations, only a minority of non-Hasidic haredim did. The authors suggest that the low number of non-Hasidic haredim giving religious explanations reflects recruitment and response bias. Those non-Hasidic haredim experiencing psychiatric problems who are more likely to give religious explanations may tend to avoid psychiatric care. Non-Hasidic haredi patients may frame their illness in non-religious terms to demonstrate commonality with clinic staff and be reluctant to voice religious explanations for fear of being perceived ‘mad’. However, these theories could apply equally to Hasidim with the same effect of reducing the number using religious explanations, a possibility the authors do not address. Another possibility suggested is that the result reflects changing attitudes within the non-Hasidic haredi community that may be more receptive than its Hasidic counterpart to outside influence.

Most studies reporting on explanatory models of illness concern mental illness, yet research shows that Hasidim invoke religious explanations of medical illnesses. Mark and Roberts (1994) found that Hasidic cancer patients’ religious interpretations including feelings of punishment and abandonment by God, anger at God, and being subjected to spiritual testing. These reflected their existing religious frameworks. Certain interpretations were unacceptable within Hasidic communities, in particular, those suggesting lack of belief in God’s benevolence, and patients felt pressure to appear devout.

Shaked (2005) and Shaked and Bilu (2006) demonstrate that different explanatory models may serve different purposes. They found that mothers’ explanations of their children’s autism incorporated medical and religious aspects: biological accounts explained how, whilst religious reasons explained why their child had autism. These religious accounts brought their situation in line with their existing framework of belief and elevated their child’s status. They used the kabbalistic theory of reincarnation of souls, explaining that in a previous life their child had been a great Zaddik who had returned to the temporal world to correct a minor sin. Their child’s limited abilities indicated how little their soul needed to achieve before reaching perfection. Possibly unsurprisingly, they ignored the negative variant of the theory that the child is a reincarnated sinner and their current situation is penance. The mothers described their own suffering as potentially enabling spiritual growth and trusted that God would grant them strength. Aligning their suffering with Biblical and historical scenarios where others had suffered and emerged with faith intact, they found perspective and inspiration.

Symptom Presentation

The content of Hasidic psychiatric patients’ symptoms and how they articulate distress may reflect cultural norms, and religious ritual and belief. Vishne et al. (2008) explore the link between psychiatric illness, menstruation and religious belief in a case series illustrating the development of obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) related to menstruation. The authors emphasise the orthopraxis of Orthodox Judaism and draw parallels between religious ritual surrounding menstruation and ritual behaviour characteristic of OCD, suggesting that these women’s OCD was based on the religious-cultural context surrounding menstruation. They refrain from asserting a causal association, allowing that religious ritual may provide the content of an individual’s obsessive–compulsive behaviour rather than being a cause of psychiatric disorder. Needell and Markowitz (2004) found that reported rates of hypersexual behaviour (HSB) were significantly higher for male Hasidic psychiatric inpatients than for matched comparisons. They suggest that the strictures Hasidism places upon sexual behaviour may lead the psychiatrically unwell to more frequently exhibit HSB than patients from other groups, noting that those behaviours proscribed by Hasidic communities are precisely those reported as HSB. The authors found no significant difference between rates of HSB reported for Hasidic women and for comparisons and suggest that this may reflect gender roles in Hasidic communities: women often have increased exposure to the secular world in comparison with men resulting in less sexual naivety.

The Stigma of Illness

Illness can attract stigma in Hasidic communities, and fear of this may reduce patients’ willingness to use services. The case study of a psychiatric rehabilitation centre in Jerusalem founded and run by Hasidim demonstrates how mental illness is stigmatised (Goodman 2009; Goodman, personal communication 2009). Mental illness was presented as deviant, with clients described in dichotomous terms including adult child and civilised savage. Carers stressed the society’s intolerance of difference, and clients were urged to conceal their ‘non-normal’ selves in public and to maintain social order. This was backed up with threats of social exclusion. Schechter et al. (2008) assert that the stigma of mental illness reduces the willingness of psychiatrically unwell Hasidim to receive treatment, suggesting that this explains the significantly lower rates of previous inpatient treatment for Hasidic psychiatric patients compared with non-Hasidic haredi patients. Trappler et al. (1995) concur, arguing that the stigma of mental illness may be overcome and treatment successfully provided to Lubavitch patients by treating them in a combined medical-psychiatric unit. Presumably, this is because patients and their families can claim medical reasons for admission not psychiatric ones, although the authors do not state this. However, Needell and Markowitz (2004) suggest that, despite the stigma of mental illness, where symptoms are extreme and at odds with community norms (symptoms of patients in this study included hypersexual behaviour), the individual may be urged to seek psychiatric treatment.

Mark and Roberts (1994) found that Hasidic cancer patients were afraid of stigma, in particular, fearing that a cancer diagnosis would negatively impact on their own or their children’s marriage prospects.Footnote 4 Frequently, this meant that they kept the diagnosis private, and were reluctant to participate in support groups where members included other Hasidim. Raz and Vizner (2008) argue that communal organisations may reinforce the stigma of certain illnesses and conditions. They explored women’s experiences of using a community-based programme of premarital genetic carrier testing and matching which tests for 10 autosomal recessive diseases with high prevalence amongst Ashkenazi Jews. Individuals receive identification numbers, not their test results. When a prospective spouse is suggested, the parties submit their numbers to the programme. If they carry the same recessive trait, they are told that marriage is inadvisable. The authors argue the message that ignorance of one’s carrier status is preferable, and the programme’s emphasis on the heavy burden of the diseases tested for and the difficulties getting married one’s remaining children would experience increase stigma. Concern that their daughter, due to the stigma of her psychiatric illness, might not find a good marriage partner appears to be the main explanation for her parents’ decision to withhold all information concerning her illness from her fiancé, a decision they upheld after she married and had a child (Feinberg 2005). Unusually, this decision received Rabbinic approval: generally Rabbis do not condone such secrecy.

Illnesses do not attract stigma equally. Goddard and Helmreich (2004) found that whilst Hasidic women were anxious that illness could result in stigma, with the impact on marriage prospects of particular concern, osteoporosis was not perceived as sufficiently serious to have this affect.

Challenges to Care Provision

Ten studies report on potential challenges to the successful delivery of health care to Hasidic patients and the adaptations health care practitioners may need to make.

Stein-Zamir et al. (2008) report on the health care provision after two measles outbreaks in Hasidic communities in Jerusalem, one of which occurred in the Bratslav community (Stein-Zamir, personal communication 2008, 2009). Social and cultural factors presented challenges. For example, large family size and overcrowding impeded isolation of patients and the large social gatherings characteristic of these communities also creating difficulties. Outbreak control was further complicated because most patients and their families had limited or no previous contact with preventive health services. Reasons suggested for this are firstly that some Hasidic groups consider the State of Israel to be illegitimate and refuse contact with State agencies, including public health services; secondly, in respect of the Bratslav community, reasons may include the antipathy towards medicine characteristic of Bratslav philosophy also noted by Witztum et al. (1990). In consequence, the large majority of cases were unvaccinated.

A culturally sensitive approach increased immunisation coverage to optimal levels. Liaison with a community-based health organisation facilitated access to individuals who did not wish to publicly receive services from State organisations and enabled health officials to overcome challenges posed by the communities’ cultural insularity and rejection of secular media. Public health officials held meetings with Rabbis who urged their respective communities to vaccinate their children. These authors, together with others, notably Erez et al. (1999) who discuss the interplay between medical care and the values and social structures in a Lubavitch community, take it for granted that Rabbinic endorsement enhances community uptake of health services. Hence, Erez et al. (1999) present a harmonious picture of physician interaction with the community’s Rabbis, describing how Rabbinic endorsement enhances patient compliance with treatment, increasing the credibility of physicians and health initiatives. This points to a discontinuity, although one the authors neither state nor address, between attitudes concerning biomedicine held by Rabbis and those held by community members: whilst Rabbis assert the correctness of medical treatment, a patient may hesitate; whilst Rabbis give credence to physicians and medical services, community members may require convincing. Questions include the extent of this divergence of opinion between Rabbis and community members, and the reasons behind it. Generally, these are unaddressed throughout the literature.

Despite a satisfactory overall achievement, Stein-Zamir et al. (2008) report differing levels of success between the communities: whilst those in the first outbreak cooperated with health officials, the Bratslav community was reluctant to comply even with their Rabbis’ appeals to vaccinate. This finding points to differences between Hasidic groups and contrasts with the findings in other research reviewed here that Rabbinic exhortations to comply with medical treatment will be obeyed.

Stein-Zamir et al. (2008) and Erez et al. (1999) illustrate the involvement of Rabbis and community-based health organisations in effective care delivery. Other research corroborates this. Witztum et al. (1990) report that Rabbis may have an important role in ensuring compliance of psychiatric patients by endorsing treatment. Shaked (2005) and Shaked and Bilu (2006) found that mothers of autistic children experienced stress when visiting secular hospitals. Mothers often appealed to Rabbis, who aligned the secular agency with a religious perspective, neutralising the threat. Erez et al. (1999), Zalcberg (2009) and Shaked (2005) and Shaked and Bilu (2006) report that Rabbis or a group’s Rebbe may advise concerning appropriate treatment. The latter authors report that where Rabbinic and medical opinion clashed, often priority was given to Rabbinic advice. Goodman and Witztum (2002) found that Rabbis referred yeshiva students for psychiatric treatment. Finally, both Mark and Roberts (1994) and Goddard and Helmreich (2004) report that Hasidim may prefer to use community-based agencies for referrals to medical care.

Stein-Zamir et al. (2008) demonstrated that Hasidic communities’ sociocultural insularity may present challenges to health care delivery by impeding access to health care information. Zalcberg (2009) reports a similar finding in her study investigating how Toldos Aharon Hasidic adolescent girls acquire knowledge about menstruation.Footnote 5 She demonstrates that the group’s efforts to assert the dominance of their values involve strict control of information about the body. Instruction concerning menstruation was scant, and girls were told that secrecy was preferable. Women’s vocabulary was inadequate to discuss menstruation, both reflecting and reinforcing the inhibitions surrounding the topic. Goddard and Helmreich (2004) report that Hasidic women experienced difficulty obtaining accurate information about osteoporosis and other diseases. Additional challenges resulted from their restrictive approach to education, which meant that health education was typically viewed as a waste of time. The wish to maintain cultural insularity may affect patients’ willingness to use support services. Mark and Roberts (1994) found that Hasidic cancer patients were reluctant to use support groups whose members came from outside their community. Language preferences can also have an effect: Law and Wallfish (1991) found that parents whose main language was Yiddish stated that speech therapy in Yiddish was essential for their children.

Finally, three papers report on accommodating cultural and religious issues in psychotherapy. These include opposition to couples’ therapy and reluctance to discuss one’s parents in terms the patient considers negative (Paradis et al. 1996). Witztum et al. (1990) discuss the psychotherapeutic techniques used in treating Bratslav patients who frequently used kabbalistic terminology to articulate distress. Familiarity with this, respect for normative Bratslav practice, and using interpretations couched in terms of the patient’s frame of reference assisted in both establishing a therapeutic relationship and directing treatment.

The criticism has already been made that the large majority of authors do not contextualise their findings against the background of research conducted in other populations and therefore are unable to provide a complete analysis of the extent to which their findings are idiosyncratic of Hasidic populations. Our examination of this literature in respect of spiritual healing, stigma and use of religious explanatory models indicates that patients from other religious or ethnic groups may share beliefs and behaviours similar to those exhibited in the Hasidic samples. It is regrettable that the authors of Hasidic studies did not draw upon the wider literature in their own analyses and discussions. For example, echoing the findings that Hasidic patients have recourse to spiritual healing (Dein 2002, 2004a, b; Littlewood and Dein 1995; Shaked 2005; Shaked and Bilu 2006), Ismail et al. (2005) found that Muslim, Sikh and Hindu patients with epilepsy in the United Kingdom used different religious and spiritual treatments in the quest for a cure, often after the perceived failure of biomedicine. These included prayer, recitation of religious texts, pilgrimages, religious healers and amulets. Patients from other religious or ethnic groups use religious explanatory models to account for a range of illnesses in ways which resemble findings from Hasidic populations. For example, Koffman et al. (2008) found that some respondents in their sample of Black Caribbean and White British cancer patients used religious accounts and Biblical texts to comprehend their cancer, creating a narrative that provided a meaningful and accessible path through their experience of illness. In the United States, Skinner et al. (2001) found that Latino families used religious frameworks to interpret their children’s developmental disabilities. Stigma attaching to illness is not unique to Hasidic populations. Flanagan and Holmes (2000) and Wilson and Luker (2006) report that cancer patients in the wider populations and members of their families felt stigmatised, experiencing social exclusion and isolation. Mirroring the findings of Mark and Roberts (1994), Chapple et al. (2004) found that fear of stigma could influence lung cancer patients in their decisions to keep their diagnosis secret and to refrain from using support groups. Kwok et al. (2005) found that fear of stigmatisation was a barrier to mammography uptake in Chinese-Australian women. Stigma against the mentally ill is well reported: Corrigan et al. (2000) report that individuals with mental illnesses are viewed more harshly than those with physical illnesses, whilst the US Department of Health and Human Services (1999) reports that stigma is the most significant obstacle to the treatment of mental disorders.

Conclusions

This is the first review of the literature investigating health care behaviours and beliefs in Hasidic populations. Despite, at times significant, methodological shortcomings, the reviewed studies reveal that Hasidic Jews express particular beliefs and behaviours in relation to illness and health care across a variety of clinical conditions. Research, largely unconsidered by these authors, indicates that patients from other ethnic and religious groups may express similar beliefs and behaviours. However, those studies that provide in-depth analysis of Hasidic thought and practice suggest that, despite areas of commonality with other groups, some behaviour and beliefs of Hasidim is idiosyncratic, reflecting specific religious and sociocultural characteristics, with implications for clinical practice.

Although religious figures have a recognised role in health care and chaplains frequently are members of multidisciplinary teams, particularly in oncology and palliative care, clinicians unused to working with Hasidic patients may be unfamiliar with the ways in which Hasidic religious authorities may participate in these patients’ coping and decision-making. Whilst patients from other religious groups approach chaplains for religious support (Flannelly et al. 2007), to discuss religious and existential issues (Strang and Strang 2002), for psychosocial support (Wright 2001), and to discuss diagnosis, prognosis and symptoms (Strang and Strang 2002), the reviewed studies indicate that Hasidic patients approach their religious authorities for different reasons, including spiritual healing, medical referrals and involvement in treatment decisions. Flannelly et al. (2007) suggest that pastoral intervention varies according to the religious group to which chaplain and patient are affiliated, with interventions reflecting practices normative to that group. Hasidic Judaism emphasises comprehensive orthopraxis, as well as orthodoxy, together with mystical practices and beliefs. Hence, it is unsurprising that contact between Hasidic patients and Hasidic religious authorities includes activities that patients from other religious groups may not expect or require of their clergy.

The involvement of Rabbis or a Rebbe in patients’ decision-making could be perceived as implying denial or avoidance of personal responsibility. Yet research with haredi breast cancer patients indicates that patients who involved Rabbis in their treatment decisions took their responsibilities seriously. They took an active role in the process, carefully selecting the Rabbi who they judged had the knowledge and experience to make the best decision on their behalf, and providing information regarding their personal situation and treatment preferences (Coleman-Brueckheimer et al. 2009). By involving a Rabbi in their decisions, participants aimed to ensure that their actions accorded with Halacha and hence with God’s will and that they fulfilled their responsibilities as haredi Jews. Lee et al. (2006) report that a sense of control and continuity of meaning following a cancer diagnosis is associated with positive psychological adjustment. In choosing to consult their Rebbe or Rabbi, Hasidim participate in a religiously and socially sanctioned method of decision-making continuous with their beliefs. By subjecting treatment decisions to these methods of decision-making, they impose meaning on their illness and on the activities that take place in relation to it. By enabling this method of decision-making for those who desire it, and by facilitating Hasidic religious authorities by engaging in open discussion, subject to patient consent, clinicians may bring benefits for their Hasidic patients.

Interpretations of illness reflect both personal and social constructions of meaning. Amongst its functions, religion is a cognitive schema providing representations of the world assisting individuals in making sense of their experiences. Research in other populations suggests that those who have established strong religious beliefs are particularly likely to use religious explanations that preserve those beliefs (Pargament 1997, p. 207) and that individuals confronting the ‘boundary conditions of life’, such as serious illness, are more likely to find religious interpretations of their illness compelling (Pargament 1997, p. 153). Hence, it is unsurprising that Hasidic participants in the studies reviewed here incorporated religious elements in their explanatory models of illness. Koffman et al. (2008) argue that patients’ use of religious explanatory models should not automatically be interpreted as implying denial or avoidance of personal responsibility. Their findings indicate that patients’ use of religious models was a deliberate attempt to understand cancer and its impact. Whilst use of religious models can have a positive impact, Fitchett et al. (2004) note that some patients may experience religious struggle leading to poorer outcomes resulting from their attempts to integrate serious illness into their existing beliefs. Similarly, Gall (2004) found that religious interpretations of illness could be detrimental to well-being: prostate cancer patients who associated cancer with God’s anger experienced poor emotional and social functioning. Whilst demonstrating respect for religious explanatory models may aid a therapeutic relationship, clinicians should remain aware of the possible negative effect on well-being patients may experience. The religious-cultural context may influence the illness experience in other ways, particularly symptom presentation in mental illness. Demonstrating respect for and familiarity with the culturally specific ways in which psychiatric patients may express and articulate their distress can aid clinicians’ therapeutic relationships with their Hasidic clients. However, Needell and Markowitz (2004) caution against the effects of transference that may lead the clinician to observe idiosyncratic behaviour or beliefs in respect of Hasidic patients where there are none.

Hasidim may be less educated concerning health care and illness prevention than members of the wider population due to sociocultural insularity, and clinicians may find implementing successful health education programmes a challenge. Liaison with religious authorities and community-based health care organisations may provide a valuable access point to these communities, enhancing both individual and group compliance and the credibility of physicians and health services. However, as research reviewed above demonstrates, such involvement does not always have this result. Other challenges to care provision may be posed by language barriers, and general mistrust and reluctance to engage with the medical profession on the part of some groups. The effects and fear of stigma may impact on patient outcome and on willingness to engage with services. Additionally, clinicians in Israel may face challenges when working with Hasidic groups who do not recognise the legitimacy of the State of Israel and refuse on principle to engage with government authorities.

As we have shown, there is a paucity of research into the health care behaviours and beliefs of Hasidic Jews, and much of the extant literature is subject to methodological shortcomings. Further research, of high methodological and analytical quality, is required in this area. Such research might examine the role of specific theologies in understandings of health and help seeking; the impact of specific religious practices such as prayer and the reading of religious texts on physical and mental health; tensions between religious and biomedical explanatory models and the role of the Rebbe in the provision of culturally appropriate health care. More specifically, in their role as culture broker, the spiritual leader may facilitate communication between the Hasidic community and mainstream biomedical health care providers. The findings of such research will better inform the provision of culturally competent care to patients from this group and potentially improve both health and well-being.

Notes

The Lubavitch movement was founded in the late eighteenth century by Shneur Zalman of Liadi (1745–1812) in Imperial Russia. In 1940, the headquarters moved to Brooklyn, New York.

Menachem Mendel Schneerson (1902–1994), the last Lubavitcher Rebbe.

Bratslav Hasidism was founded by Rebbe Nahman of Bratstlav (1772–1810) in 1802 in the Ukrainian town after which the group is named. No successor was designated and the group has been without a Rebbe since his death.

Introductions for the purpose of marriage take place within a formal system of matchmaking.

Toldos Aharon (lit. Generations of Aharon) was founded in the mid-twentieth century by Avrohom Yitzchok Kahn (d. 1996) and has its headquarter in Mea Shearim in Jerusalem. Toldos Aharon is characterized by fervent and emotional prayer and an exceptionally strict lifestyle.

References

Chapple, A., Ziebland, S., & McPherson, A. (2004). Stigma, shame, and blame experienced by patients with lung cancer: Qualitative study. British Medical Journal, 328(7454), 1470–1474.

Coleman-Brueckheimer, K., Spitzer, J., & Koffman, J. (2009). Involvement of Rabbinic and communal authorities in decision-making by haredi Jews in the UK with breast cancer: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Social Science and Medicine, 68, 323–333.

Commission for Social Care Inspection (CSCI). (2008). Putting people first: Equality and diversity matters 2. Providing appropriate services for black and minority ethnic people. London: CSCI.

Corrigan, P. W., River, L. P., Lundon, R. K., Uphoff Wasowski, K., Campion, J., Mathisen, J., et al. (2000). Stigmatizing attributions about mental illness. Journal of Community Psychology, 28(1), 91–102.

Dan, J. (1998). Hasidism: The third century. In A. Rappoport-Albert (Ed.), Hasidism reappraised. Oxford: Littman.

Dein, S. (2002). The power of words: Healing narratives among Lubavitcher Hasidim. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 16(1), 41–63.

Dein, S. (2004a). From chaos to cosmogency: A comparison of understandings of the narrative process among Western academics and Hasidic Jews. Anthropology and Medicine, 11(2), 135–147.

Dein, S. (2004b). Religion and healing among the Lubavitch community in Stamford hill, North London. Lewiston, Queenston, Lampeter: The Edwin Mellen Press.

Dein, S. (2006). Culture and cancer care anthropological insights in oncology. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Department of Health (DH). (2007). Positive steps: Supporting race equality in mental healthcare. London: DH.

Erez, R., Rabin, S., Shenkman, L., & Kitai, E. (1999). A family physician in an Ultraorthodox Jewish village. Journal of Religion and Health, 38(1), 67–71.

Feinberg, S. S. (2005). Issues in the psychopharmacologic assessment and treatment of the Orthodox Jewish patient. CNS Spectrums, 10(12), 954–965.

Fitchett, G., Murphy, P. E., Kim, J., Gibbons, J. L., Cameron, J. R., & Davis, J. A. (2004). Religious struggle: Prevalence, correlates and mental health risks in diabetic, congestive heart failure, and oncology patients. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 34(2), 179–196.

Flanagan, J., & Holmes, S. (2000). Social perceptions of cancer and their impacts: Implications for nursing practice arising from the literature. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 32(3), 740–749.

Flannelly, K. J., Weaver, A. J., & Handzo, G. F. (2007). A three-year study of chaplains’ professional activities at Memorial Sloan-kettering cancer center in New York City. Psycho-Oncology, 12(8), 760–768.

Gall, T. (2004). Relationship with God and the quality of life of prostate cancer survivors. Quality of Life Research, 13(8), 1357–1368.

Goddard, D., & Helmreich, W. B. (2004). Ethnicity and health: Attitudes of Italian Americans and Hasidic Jews towards osteoporosis. Humboldt Journal of Social Relations, 28(1), 55–82.

Goodman, Y. C. (2009). “You look, thank God, quite good on the outside”: Imitating the ideal self in a Jewish Ultra-Orthodox rehabilitation site. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 23(2), 122–141.

Goodman, Y. C. (2009). Personal communication (email), 31 May 2009.

Goodman, Y., & Witztum, E. (2002). Cross-cultural encounters between careproviders: Rabbis’ referral letters to a psychiatric clinic in Israel. Social Science and Medicine, 55, 1309–1323.

Ismail, H., Wright, J., Rhodes, P., & Small, N. (2005). Religious beliefs about the causes of epilepsy. British Journal of General Practice, 55(510), 26–31.

Kirmayer, L. (2004). The cultural diversity of healing: Meaning, metaphor and mechanism. British Medical Bulletin, 69, 33–48.

Koffman, J., Morgan, M., Edmonds, P., Speck, P., & Higginson, I. J. (2008). “I know he controls cancer”: The meanings of religion among Clack Caribbean and White British patients with advanced cancer. Social Science and Medicine, 67(5), 780–789.

Kwok, C., Cant, R., & Sullivan, G. (2005). Factors associated with mammographic decisions of Chinese-Australian women. Health Education Research, 20(6), 739–747.

Law, J., & Wallfish, T. (1991). Do ‘minority’ groups have special needs? Speech therapy and the Chasidic Jewish community in north London. Child: Care, Health and Development, 17, 319–329.

Lee, V., Cohen, S. R., Edgar, L., Laizner, A. M., & Gagnon, A. J. (2006). Meaning-making intervention during breast or colorectal cancer treatment improves self-esteem, optimism, and self-efficacy. Social Science and Medicine, 62, 3133–3145.

Littlewood, R. (1983). The antinomian Hasid. British Journal of Medical Psychiatry, 56, 67–78.

Littlewood, R., & Dein, S. (1995). The effectiveness of words: religion and healing among the Lubavitch of Stamford Hill. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 19, 339–383.

Mark, N., & Roberts, L. (1994). Ethnosensitive techniques in the treatment of the Hasidic cancer patient. Cancer Practice, 2(3), 202–208.

Mintz, J. R. (1994). Hasidic people: A place in the new world. Cambridge, MA, London: Harvard University Press.

Needell, N. J., & Markowitz, J. C. (2004). Hypersexual behaviour in Hasidic Jewish inpatients. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 192(3), 243–246.

Paradis, C. M., Friedman, S., & Hatch, M. J. (1996). Cognitive behavioral treatment of anxiety disorders in Orthodox Jews. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 3, 271–288.

Pargament, K. (1997). The psychology of religion and coping: Theory, research, practice. New York/London: The Guilford Press.

Raz, A. E., & Vizner, Y. (2008). Carrier matching and collective socialization in community genetics: Dor Yeshorim and the reinforcement of stigma. Social Science and Medicine, 67, 1361–1369.

Rosen, D. D., Greenberg, D., Schmeidler, J., & Shefler, G. (2008). Stigma of mental illness, religious change, and explanatory models of mental illness among Jewish patients at a mental-health clinic in North Jerusalem. Mental Health Religion and Culture, 11(2), 193–209.

Schechter, I., Langner, E., & Bergeron. (2008). Diagnostic, clinical and sociodemographic description of an ultra-orthodox and Hasidic Jewish population: an outpatient mental health clinic sample. Unpublished. Presented at Nefesh International 2008 Conference.

Shaked, M. (2005). The social trajectory of illness: Autism in the ultraorthodox community in Israel. Social Science and Medicine, 61, 2190–2200.

Shaked, M., & Bilu, Y. (2006). Grappling with affliction: Autism in the ultraorthodox community in Israel. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 30, 1–27.

Sheinfeld, H., Gal, M., Bunzel, M. E., & Vishne, T. (2007). The etiology of some menstrual disorders: A gynecological and psychiatric issue. Health Care for Women International, 28, 817–827.

Skinner, D. G., Correa, V., Skinner, M., & Bailey, D. B., Jr. (2001). Role of religion in the lives of Latino families of young children with developmental delays. American Journal of Mental Retardation, 106(4), 297–313.

Stein-Zamir, C. (2008). Personal communication (email) dated 18 February 2008.

Stein-Zamir, C. (2009). Personal communication (email) dated 21 April 2009.

Stein-Zamir, C., Zentner, G., Abramson, N., Shoob, H., Aboudy, Y., Shulman, L., et al. (2008). Measles outbreaks affecting children in Jewish ultra-orthodox communities in Jerusalem. Epidemiology and Infection, 136, 207–214.

Strang, S., & Strang, P. (2002). Questions posed to hospital chaplains by palliative care patients. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 5(6), 857–864.

Trappler, B., Greenberg, S., & Friedman, S. (1995). Treatment of Hassidic Jewish patients in a general hospital medical-psychiatric unit. Psychiatric Services, 46(8), 833–835.

US Department of Health, Human Services (HSS) Office of Minority Health (OMS). (2001). National standards for culturally and linguistically appropriate services in health care final report. Rockville, MD: HSS OMS.

US Department of Health, Human Services (HSS) Office of the Surgeon General (OSG). (1999). Mental health: A report of the surgeon general. Rockville, MD: HSS OSG.

Vishne, T., Misgav, S., & Bunzel, M. E. (2008). Psychiatric disorders related to menstrual bleeding among an ultra-orthodox population: Case series and literature review. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 54(3), 219–224.

Wertheim, A. (1992). Law and custom in hasidism. Hoboken, NJ: KTAV Publishing House.

Wilson, K., & Luker, K. A. (2006). At home in hospital? Interaction and stigma in people affected by cancer. Social Science and Medicine, 62(7), 1616–1627.

Witztum, E., Greenberg, D., & Buchbinder, J. T. (1990). “A very narrow bridge”; Diagnosis and management of mental illness among Bratslav Hasidim. Psychotherapy, 27(1), 124–131.

Wright, M. C. (2001). Chaplaincy in hospice and hospital: Findings from a survey in England and Wales. Palliative Medicine, 15, 229–242.

Zalcberg, S. (2009). Channels of information about menstruation and sexuality among Hasidic adolescent girls. NASHIM, 17, 60–88.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Coleman-Brueckheimer, K., Dein, S. Health Care Behaviours and Beliefs in Hasidic Jewish Populations: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J Relig Health 50, 422–436 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-010-9448-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-010-9448-2