Abstract

In this paper, a number of theoretical issues concerning rational beliefs in REBT will be discussed. In particular, a distinction will be made between rational beliefs which appear rational but are only partially rational (called here, partially formed rational beliefs) and rational beliefs that are fully rational (called here, fully formed rational beliefs). Making this distinction has a number of benefits. For example, it helps explain how people transform their partially formed rational beliefs into irrational beliefs and it provides authors of counseling and psychotherapy textbooks with clear, accurate information to pass on to their readership (Dryden 2012). A number of other issues concerning rational beliefs will also be discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The Nature, Characteristics and Types of Rational Beliefs

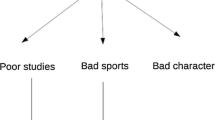

In REBT theory, rational beliefs are deemed to be at the core of psychological health and a primary goal of REBT is to help clients to change their irrational beliefs into rational beliefs. But what are rational beliefs? Basically, in REBT, rational beliefs are viewed as the opposite of irrational beliefs. Thus, irrational beliefs are considered to be rigid and extreme in nature and rational beliefs are thus considered flexible and non-extreme. The defining characteristics of irrational beliefs are that they are inconsistent with reality, illogical and lead to predominantly unhealthy results for the individual and his relationships (in this case the client was male) as well as impeding his pursuit of his personally meaningful goals (i.e. they are unempirical, illogical and dysfunctional). Correspondingly, rational beliefs are deemed to be consistent with reality, logical and lead to predominantly healthy results for the person and his relationships as well as facilitating his pursuit of his personally meaningful goals (i.e. they are empirical, logical and functional). Putting it this way shows quite clearly that there is no posited continuum between rational and irrational beliefs. They are qualitatively different from one another, not quantitatively different.

Finally, while REBT theory posits four basic types of irrational beliefs, i.e. rigid beliefs, awfulizing beliefs, discomfort intolerance (LFT) beliefs and beliefs where the self, others and/or life conditions are depreciated, it also posits four basic types of rational beliefs, i.e. flexible beliefs, non-awfulizing beliefs, discomfort tolerance beliefs and beliefs where the self, others and/or life conditions are accepted unconditionally.

Partially Formed Rational Beliefs versus Fully Formed Rational Beliefs

As I have shown in previous research, authors of counseling textbooks and even REBT therapists themselves are sometimes confused or in error about the nature of rational beliefs that are fully formed (Dryden 2012). It is therefore important that clear definitive information is given concerning the nature of such beliefs and how they differ from their partially formed rational counterparts. In this part of the paper, then, I will provide such definitive information which is derived from REBT theory.

Partially Formed Flexible Beliefs versus Fully Formed Flexible Beliefs

Let us assume that a person makes the following statement: “I want to pass my forthcoming examination.” As expressed, this belief is really a partially formed flexible belief because, although the person asserts her preference, she does not negate her demand. If she were to express her fully formed flexible belief, then she would say: “I want to pass my forthcoming examination, but I do not have to do so.” Here, the person both asserts her preference and negates her demand. These two characteristics have to be stated explicitly for it to be clear that the person’s flexible belief is fully formed.

When this person transformsFootnote 1 her partially formed flexible belief into a rigid belief, she does so as follows: “I want to pass my forthcoming examination … and therefore I have to do so.” Clients often give the short form of this rigid belief thus: “I must pass my forthcoming exam,” but as we have just seen this is comprised of a partially formed flexible belief transformed into a rigid belief.

Thus, whenever a person states her partially formed flexible belief, we do not know for sure that this truly represents a fully formed flexible belief. Thus, as shown above, the person may explicitly state: “I want to pass my forthcoming examination,” and then implicitly add (“and therefore I have to do so”). Given a person’s ability to add an implicit rigidity to an explicitly stated partially formed flexibility, REBT therapists are strongly advised, when assessing their clients’ beliefs, to focus on these clients’ stated partially formed flexible beliefs and to determine whether these represent fully formed flexible beliefs or have been transformed into rigid beliefs. This can be done by taking the partially formed flexible belief, e.g. “I want to pass my forthcoming examination,” and by asking them to state which of the two additions represents their truly held belief:

- 1.

“but I don’t have to do so” or

- 2.

“and therefore I have to do so.”

When it is clear that the person’s true belief is a fully formed flexible belief, the person should be encouraged to use the full form of this belief whenever referring to it, at least until both therapist and client know that the client is still holding this fully formed flexible belief when referring to a truncated version of it.

When we take the person’s fully formed flexible belief, it becomes clear why she cannot transform this rational belief into an irrational belief. Thus, if she believes: “I want to pass my forthcoming examination, but I do not have to do so,” she cannot logically transform this into the following rigid belief: “I must pass my forthcoming examination.” However, this person can at one moment hold a fully formed flexible belief about her passing her exam and at the next moment hold a rigid belief about passing it. But these are best regarded as two separate belief episodes whereas, if the person were to transform her partially formed flexible belief into a rigid belief, this could be seen as a single belief episode.

As we have just seen, a person cannot logically hold a fully formed flexible belief about something and a rigid belief about that same thing at the very same time. She can, however, hold a partially formed flexible belief and a rigid belief at the same time and this is probably what Ellis referred to when he used to say in his advanced workshops that a person can hold a desire and a demand at the very same time.

This point about the simultaneous and consecutive adherence to beliefs also holds for partially formed and fully formed non-awfulizing beliefs, partially formed and fully formed discomfort tolerance beliefs and partially formed and fully formed acceptance beliefs.

Partially Formed Rational Derivatives versus Fully Formed Rational Derivatives

As is well known in REBT circles, rigid beliefs are regarded by Ellis as primary irrational beliefs (to denote their central position in accounting for psychological disturbance) and awfulizing beliefs, discomfort intolerance beliefs and depreciation beliefs are regarded as secondary irrational beliefs or more properly irrational derivatives from these rigid beliefs (Ellis 1994). Similarly, what I have called fully formed flexible beliefs are regarded by Ellis as primary rational beliefs (to denote their central position in accounting for psychological health) and non-awfulizing beliefs, discomfort tolerance beliefs and acceptance beliefs are regarded as secondary rational beliefs or more properly rational derivatives from these fully flexible beliefs (Ellis 1994).

Similar points can be made about partially formed and fully formed rational derivatives as were made about partially formed and fully formed flexible beliefs.

Partially Formed versus Fully Formed Non-Awfulizing Beliefs

When a person holds a partially formed non-awfulizing belief she asserts the point that it was bad that the event in question occurred, for example. Thus, in our example, the person’s partially formed non-awfulizing belief was as follows: “It would be bad if I were to fail my forthcoming examination.” Note, however, that in this belief the person does not negate the idea that it would be awful if the target event were to occur. Given this omission, we do not know whether, in fact, the belief is really a fully formed non-awfulizing belief where the person would negate the idea of awfulizing (e.g. “It would be bad if I were to fail my forthcoming exam … but it would not be awful”) or an awfulizing belief where the person would implicitly add “and therefore it would be awful if this were to occur.” Indeed, as we have seen, if the form of this belief is partial then the person could easily transform it into an irrational awfulizing belief, particularly if the evaluation of badness was strong.Footnote 2

Thus, we only know that a non-awfulizing belief is rational when it is stated explicitly in its full form, thus: “It would be bad if I were to fail my forthcoming exam, but it would not be awful.” Note that in this statement the person asserts that it would be bad if the event were to occur, but negates the proposition that it would therefore be awful if it were to happen.

Partially Formed versus Fully Formed Discomfort Tolerance Beliefs

The distinction between partially formed and fully formed discomfort tolerance beliefs is not as obvious as that between partially formed and fully formed flexible beliefs and partially formed and fully formed non-awfulizing beliefs. This is because asserting that you can tolerate something seems to incorporate negating the idea that you cannot tolerate it. The problem comes back into focus when the client does not use “tolerance” words interchangeably. Thus, the following belief seems fully rational: “If I were to fail my exams, it would be a struggle, but I could tolerate it.” However, the person could add the statement either explicitly (if asked) or implicitly, “but if I did fail the exam I would fall apart.” In this case, it is harder to encourage the person to develop a fully formed discomfort tolerance belief since you do not know if you have exhausted all the words she uses to denote a discomfort intolerance belief. What you can do in this situation is to explain the concept of fully formed discomfort tolerance beliefs to the client and elicit from her the key words she uses to denote such beliefs. You can then ensure that she negates her most commonly used discomfort intolerance belief component. In our example, “falling apart” was for this client a common discomfort intolerance belief component so that in her mind she could tolerate something, but still fall apart. Thus, the person’s partially formed discomfort tolerance belief was: “I could tolerate it if I were to fail my forthcoming examination,” but this really hid an implicit discomfort intolerance belief: “but if it were to happen I would fall apart.” Her fully formed discomfort tolerance belief would be as follows: “It would be a struggle for me to put up with failing my forthcoming exam, but I could tolerate it and if it happened I would not fall apart.”Footnote 3

Although not strictly part of a fully discomfort tolerance belief, I have argued that the addition of a “worth it” component makes the instrumental nature of a fully discomfort tolerance belief far more clear than its omission (Dryden 2009). Thus, if you compare the statement: “It would be hard for me to put up with failing my exam, but I could tolerate doing so” with: “It would be hard for me to put up with failing my exam, but I could tolerate doing so and it would be worthwhile for me to do so,” you will see what I mean.

Partially Formed versus Fully-Formed Unconditional Self-Acceptance Beliefs

In this section, the focus will be on unconditional self-acceptance (USA) beliefs although, as is well known, acceptance beliefs can also refer to one’s attitude about other people and about life conditions. When a person articulates a partially formed self-acceptance belief, she often makes a statement about who she is not. Thus, in our example the person’s partially formed self-acceptance belief was as follows: “If I were to fail my forthcoming examination, it would not prove that I was a failure.” This seems rational until you note that the person has not stated who she thinks she would be if she were to fail the exam. Thus, our client could go on to say: “But if I did fail the examination, I would be less worthy than I would be if I were to pass it.” If she did this, she would be revealing that what on the surface appeared to be a self-acceptance belief was nothing of the kind. Indeed, it turned out to be a subtle form of self-depreciation belief.

Thus, when a person negates a self-depreciation statement, she has revealed a partially formed self-acceptance belief and in doing so we cannot know whether or not she may hold an implicit self-depreciation belief. Or even if she does not, we cannot rule out the possibility that she might later transform this partially formed self-acceptance belief into a self-depreciation belief.

A fully formed unconditional self-acceptance belief, in contrast, makes clear both who the person believes she is not and who she believes herself to be. We have dealt with the case where the client negates a self-depreciation statement, but what can she say when she asserts an unconditional self-acceptance statement? To answer this question a brief consideration of the REBT concept of unconditional self-acceptance will be made.

In REBT theory, unconditional self-acceptance means that the person refrains from making any kind of self-rating. Here, the person acknowledges that she is a complex, unrateable, unique process who has good aspects, bad aspects and neutral aspects and is in essence fallible. REBT theory also advocates (although less enthusiastically) the concept of unconditional, positive self-rating. Here, the person regards herself as worthwhile no matter what. If she wishes to assert a reason for this she can say: “I am worthwhile because I am alive, human and unique.” Normally, however, the person asserts her worth for reasons that change, e.g. “I am worthwhile because I passed my examination.” This is problematic because the person’s worth fluctuates according to changing circumstances. This is REBT’s major objection to the concept of self-esteem: it is conditional and allows for worth to vary, as was revealed in the implicit statement of the person in our example: “But if I did fail the examination, I would be less worthy than I would be if l were to pass it.”

A fully formed unconditional self-acceptance statement, then, should assert who the person is and this statement should be either an unconditional self-acceptance statement or an unconditional, positive self-rating statement. Thus, the person in our example could say either: “If I do not pass my forthcoming examination, that would be bad,Footnote 4 but it does not mean that I am a failure, it means that I am a fallible, unique, unrateable complex human being who has failed this time. Nothing can alter this fact about me” or “If I do not pass my forthcoming examination, that would be bad,Footnote 5 it does not mean that I am a failure. I am still worthwhile even though I failed for my worth depends on my aliveness, my uniqueness and my being human.” As you can see, in the first fully formed self-acceptance statement the person asserts an unconditional self-acceptance belief and in the second, she asserts an unconditional, positive self-rating.

In summary, a fully formed unconditional self-acceptance belief has the following features. First it acknowledges the badness of the identified self-aspect or adversity. Second, it negates a self-depreciation belief. Third, it asserts an unconditional self-acceptance belief or an unconditional positive self-rating belief. It is this unconditionality that is important and without it the person may hold an implicit self-depreciation belief and would be in danger of transforming his partially-formed self-acceptance belief into a subtle self-depreciation belief.

Other Issues

In this section, four further issues will be discussed: (1) the difference between the concepts of escalation and transformation when outlining the relationship between partially formed rational beliefs and irrational beliefs; (2) the importance of probing for conditions where the person would think irrationally when he (in this case) holds a rational belief; (3) the importance of distinguishing between two different types of preferences; and (4) the importance of distinguishing between true preferences and introjected, false preferences.

Escalation Versus Transformation

In working with clients, Ellis used to speak of the tendency of people to escalate their rational beliefs into irrational beliefs (Yankura and Dryden 1990). However, this concept is problematic for two reasons. First, it does not make an important distinction between beliefs which appear rational, but are only partially formed, on the one hand and beliefs that are fully rational on the other. Thus, as I have shown, the statement “I want to pass my forthcoming exams” seems rational (because it posits a desire statement and there is no sign of a demand statement), but it may not be rational. Thus, as stated, it is possible for me then to conclude “and therefore I have to do so,” a statement which would reveal an irrational belief. By contrast, the statement “I want to pass my forthcoming exams, but I don’t have to do so” is a fully formed rational belief in that it is fully flexible.

The second reason why the concept of escalation is problematic in REBT theory is that it implies that a partially formed rational belief exists on the same continuum as an irrational belief.Footnote 6 Theoretically, this is incorrect. A partially formed rational belief (e.g. “I want to pass my forthcoming exam”) does not naturally lead to either an irrational belief (“I must pass my forthcoming exam”) or a fully formed rational belief (“I want to pass my forthcoming exam, but I don’t have to do so”). It exists on its own, ready to be transformed into an irrational belief (i.e. “I want to pass my forthcoming exam … and therefore I must do so”Footnote 7) or a fully formed rational belief (i.e. “I want to pass my forthcoming exam, but I don’t have to do so”). Consequently, it is more accurate to say that a person transforms her partially formed rational belief into an irrational belief than it does that she escalates it into an irrational belief.

Using the concept of transformation rather than that of escalation makes it clearer that an irrational belief and a rational belief can both be placed along its own continuum which describes varying strength of conviction. Thus, an irrational belief can be held with weak conviction, moderate conviction or strong conviction and the same applies to a rational belief.

The Strength of Partially Formed Rational Beliefs and the Transformation Process

Although we don’t have empirical evidence to support this point, REBT theory hypothesizes that people are more likely to transform their partially formed rational beliefs into irrational beliefs when the former are strong than when they are moderate or weak. This will be illustrated with reference to partially formed flexible beliefs and rigid beliefs. Thus, the person in our example is more likely to transform her partially formed flexible belief into a rigid belief when it is strong: (“I really want to pass my forthcoming exam and therefore I have to do so”) than when it is moderate (“I would rather like to pass my forthcoming exam and therefore I have to do so”) or weak (“I suppose I do want to pass my forthcoming exam and therefore I have to do so”). The transformations outlined in the latter two situations are possible, but less likely to be made than that illustrated in the first situation.

The converse of this is that it is easier to develop a fully formed flexible belief preference from a partially formed flexible belief when the latter is weak (“I suppose I do want to pass my forthcoming exam, but I don’t have to do so”) or moderate (“I would rather like to pass my forthcoming exam, but I don’t have to do so”) than when it is strong (“I really want to pass my forthcoming exam, but I don’t have to do so”). While the latter fully formed flexible belief is the hardest to achieve, it is perhaps the very hallmark of psychological health if the person can truly believe it.

Probing for Possible Irrationalities when a Client Holds a Rational Belief

When you have helped a client to construct a rational belief, it is still important to check whether or not the person holds a further irrational belief which may mean that the stated rational belief is dependent upon the existence of certain conditions. Consider this statement: “I am not a failure for failing my examination. I am a fallible human being who has failed this time.” This seems to be a rational belief, but the client who made it went on to say: “I can accept myself if I fail the exam, but I must not fail it really badly. If I did I would be a failure.” Another example of this was the client who, in response to my questioning, admitted that while she could accept herself if she made mistakes, this would only be true if those mistakes were relatively small: “I must not make really big mistakes and if I did I would be a failure.” In both these examples it transpired that the client’s rational belief was conditional.

If a client puts forward a rational belief such as: “I am not a failure for failing my examination. I am a fallible human being who has failed this time,” ask her the following questions: (1) “Are there any circumstances relevant to this situation where you would consider yourself a failure?” and (2) “You are not demanding that you must pass your exam, but can you think of any circumstance relevant to failing where you would make a demand on yourself?” If these questions reveal the conditionality of the stated rational beliefs, help the person to make these beliefs unconditional by disputing the implicit rational beliefs.

Distinguishing between Two Different Types of Preference

The statement: “I would prefer to pass my forthcoming examination, but I do not have to do so” is clearly a fully formed flexible belief, since it asserts what the person wants and negates the idea that she must achieve what she wants. Now consider the following statement: “It would be better if I revised for my exam since it would increase my chances of passing it, but I do not have to do so.” This is also a fully formed flexible belief in that it negates the demand, but in this case the person does not want to do the activity in question, i.e. revise for her exam.

Thus, one type of preference points to something that the person wants and a different type of preference points to what the person does not want to do, but is in her interests to do. In other words, in this latter type of preference the person acknowledges that she has to do something undesirable (i.e. revise for her exam) in order to get what she does want (passing the exam). Both are fully formed flexible beliefs as we have seen, but they involve different types of preference. This becomes important when challenging the irrational versions of these beliefs, which are (1) “I must pass my forthcoming exam” and (2) “I must revise for my exam.”

In the first example, it makes sense to ask the person: “Why do you have to achieve what you want, i.e. passing your exam?” However, this type of question would not make sense in the second example because the person does not want to revise for her exam. In this case, it is better to ask: “Why do you have to do what you don’t want to do, i.e. revise for your exam?” The answer to the first question is “I don’t have to pass the exam, but I do want to pass it.” The answer to the second question is: “I don’t have to revise for my exam, but it is in my interests to do what I don’t want to do to get the outcome that I do want.”

Thus, it is important to distinguish between these two different types of preference and the different types of alternative demands that the person may make when they transform their preferences into demands.

Distinguishing between True Preferences and Introjected, False Preferences

It sometimes happens that a client’s preference may not represent what the person truly believes, but what he has introjected (i.e. taken from others or from other sources without consideration) from others. An example of an introjected, false preference occurred with a client who stated that he wanted to become an accountant. When asked why he wanted to pursue this career, he found it difficult to come up with plausible reasons. He was then asked who else apart from himself wanted him to become an accountant. He replied that his father wanted this. He was then asked how he would respond if his father changed his mind and didn’t want him to pursue this occupation; he replied that in this case he would study to be a musician which was a career that he truly wanted.

Although Ellis has stated that REBT therapists do not generally challenge a client’s preferences, it is useful to do so if you have a hunch that the person’s preference may be introjected and false. The clues to the existence of such a preference are as follows: (1) the person finds it difficult to provide persuasive reasons for his preference; (2) other people think that he “should” have such a preference and (3) if presented with a scenario where these people no longer want him to have this preference, the person is prepared to relinquish it.

When a person has an introjected false preference, this is often a sign that he holds an irrational belief with respect to the people who have an interest in him having the preference. This irrational belief relates to the person believing that he must have the approval of these others. If this is the case, this belief should become the focus for therapeutic intervention.

Summary

In this paper, I have tried to show that rational beliefs can be clearly understood if all their component parts are included when these beliefs are referred to. Doing so helps therapists, clients and others be clear about (1) what are truly rational beliefs; (2) what appear to be rational beliefs but are not; and (3) what are clearly irrational beliefs (Dryden 2012). I have also covered a number of issues which arise when rational beliefs are discussed with clients in therapy. It is my hope that this paper will stimulate further theoretical work by REBT scholars.

Notes

I will discuss this concept of transformation later in the paper.

I will discuss the issue of the strength of partially formed rational beliefs and the transformation process later in the paper.

I have included here what I have called the struggle component to combat the view that a discomfort tolerance belief implies that it is or should be easy to tolerate adversity.

I have included this evaluation of “it” (an aspect of the person or an actual inferred event) as part of a fully formed unconditional positive self-rating statement to stress that negative evaluations of such aspects are realistic and healthy.

See note 4.

While escalators go up, the bottom of the escalator is on the same continuum as the top of the escalator.

In its short form: “I must pass my forthcoming exam.”

References

Dryden, W. (2009). Rational emotive behavior therapy: Distinctive features. Hove, East Sussex: Routledge.

Dryden, W. (2012). The ABCs of REBT revisited: Perspectives on conceptualization. New York: Springer.

Ellis, A. (1994). Reason and emotion in psychotherapy: A comprehensive method of treating human disturbance. Revised and updated. New York: Birch Lane Press.

Neenan, M., & Dryden, W. (1999). Rational emotive behaviour therapy: Advances in theory and practice. London: Whurr.

Yankura, J., & Dryden, W. (1990). Doing RET: Albert Ellis in action. New York: Springer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

An earlier version of this article was published in: Neenan and Dryden (1999).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dryden, W. On Rational Beliefs in Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy: A Theoretical Perspective. J Rat-Emo Cognitive-Behav Ther 31, 39–48 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-012-0158-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-012-0158-4