Abstract

Over the past decade, there has appeared a surge of research interest in language learners’ academic engagement and psychological well-being as important factors in improving the quality of education. However, research on the roles of English as a foreign language (EFL) teachers’ affective scaffolding in enhancing the academic engagement and psychological well-being of their students is relatively scant. Inspired by this gap, the current study aimed to investigate the impact of Chinese EFL teachers’ affective scaffolding on their learners’ academic engagement and psychological well-being. To this end, a total number of 1968 Chinese EFL learners participated in this questionnaire survey. The results of the study showed that EFL teachers’ affective scaffolding positively and significantly predicted students’ academic engagement and psychological well-being. More specifically, it was found that teachers’ affective scaffolding explained about 73% and 65% of variances in EFL students’ academic engagement and psychological well-being. Moreover, it was found that psychological well-being and academic engagement were positively correlated and predicted 56% of each other’s variances. In accordance with these findings, educators are recommended to build up a harmonious teacher-student relationship to foster students’ psych-emotional development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

One of the goals of educational systems is to develop professional and knowledgeable teachers, increase the quality of education and learning, and design effective educational systems (Acton & Glasgow, 2015; Han & Wang, 2021; Romano et al., 2020). The development of teachers’ professional knowledge is done through meeting the needs of students and knowing their individual differences (Al-Hoorie, 2016; Burić & Macuka, 2018; Ryan & Patrick, 2001). Teachers’ knowledge of learners’ individual differences covers two areas of students’ academic engagement and basic psychological needs (Ryan & Deci, 2017; Ryff, 1989; Shakki, 2022). It is asserted that students’ basic psychological needs vary across cultures and educational systems (Jang et al., 2010; Ryff & Keyes, 1995). Depending on what beliefs exist in a culture, students’ basic needs and expectations will vary (Kalokerinos et al., 2015). However, satisfying such needs and establishing a caring environment are pivotal for students’ social functioning and growth (Carmeli et al., 2009; Chen & Kent, 2020; Ryff, 2014). One of the most essential needs that teachers must consider in second/foreign language education is students’ psychological well-being (PWB), which can serve as a source of excellence (Warr et al., 2018). It refers to one’s perception of how well his/her life is going, feeling good, and functioning efficiently (Huppert, 2009). It also concerns a person’s prime psychological functioning and experience (Tang et al., 2019). PWB is the consequence of several positive attributes inundated in one’s functioning (Ryff & Keyes, 1995). With the growth of positive psychology (PP) and the emergence of innovative approaches to scrutinize the roles of emotions in the teaching and learning process (Derakhshan, 2022a; Derakhshan, Wang, et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2021; Wang, Derakhshan, & Pan, 2022), PWB enshrined and research approved its relationship with metacognitive development (Naeem et al., 2021), work engagement (Greenier et al., 2021), L2 grit (Derakhshan, Dewaele, et al., 2022; Derakhshan, Solhi, et al., 2023), emotional intelligence (Guerra-Bustamante et al., 2019), success (Fan & Wang, 2022), immunity (Wang et al., 2022), and emotion self-regulation (Freire & Tavares, 2011).

Another construct that PWB can affect or interact with is students’ academic engagement (Ainsworth & Oldfield, 2019; Ryff et al., 2007). When the psychological needs of students are met in a learning environment, they engage constructively in classroom activities (Al-Murtadha, 2019; Sasaki et al., 2020). Otherwise, they retreat and get frustrated in academia. Therefore, academic engagement best flourishes in a positive motivational growth model as posited by self-determination theory (SDT) (Lee et al., 2020; Schenke et al., 2015). Teachers are claimed to play a significant role in providing this opportunity (Lee et al., 2020; Vesely et al., 2013; Wang, Derakhshan, & Azari Noughabi, 2022; Wang, Derakhshan, & Rahimpour, 2022). Their attention to students’ PWB and active engagement in learning content enhances students’ skills and talents and paves the way for collaborative learning (Mikus & Teoh, 2021).

Nevertheless, these positive outcomes do not occur without appropriate scaffolding and affective support by the teachers. Scaffolding, as an instructional technique, grew out of Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory to generate growth and independence in learners. It can take many forms including individualistic, collective, synchronic, diachronic, cognitive, and affective (Saarinen, 2020). Of these, the affective form of teacher scaffolding is contended to be more penetrating given its utilization of environmental adjustment to support emotions, moods, bodily affective styles, and background feelings (Colombetti & Krueger, 2015; Saarinen, 2020). In education, affective scaffolding (AS) can represent different ways through which a teacher (or an expert) manipulates the environment to affect his/her students’ emotional lives. It can improve students’ classroom involvement and activate many motivational patterns (Ainsworth & Oldfield, 2019; Alavi et al., 2021; Eysenck et al., 2007; Wellborn, 1992). Likewise, teachers’ AS can create a space to meet students’ basic psychological needs including their PWB (Aubrey et al., 2020; Wilson et al., 2010). The quality of teaching and learning also increases when EFL teachers provide enough AS (Chao et al., 2017; Wolters, 2004).

This interplay among academic engagement, PWB, and AS is a cause for concern because effective education happens only in case students’ psycho-emotional factors are cared about via suitable teacher assistance (Bowling et al., 2010; Derakhshan, 2022b; Xie & Derakhshan, 2021). The quality of teachers’ affective support or scaffolding has been scientifically found to increase students’ attachment and reduce their burnout (Henry & Thorsen, 2018; Zee & Koomen, 2016). Despite previous studies that provided insightful ideas about the significance of scaffolding in L2 education, the mediating role of teachers’ AS in satisfying EFL students’ PWB and academic engagement has not been applied in practice. Against this gap, the present study intended to investigate the impact of Chinese EFL teachers’ AS on students’ academic engagement and PWB.

Review of Literature

Teachers’ Affective Support and Scaffolding

It is claimed that emotional relationships between teachers and students are a critical issue in education that influences various aspects of teaching and learning in the class (Derakhshan et al., 2020; Zhang, 2020). Affective support and scaffolding is an aspect of interpersonal relationships that is very significant for fostering L2 learning (Dörnyei & Ushioda, 2021; Paris, 2013). AS largely depends on the nature of classroom rapport and the context in which it is given (Burke-Smalley, 2018). It is a philosophy of mind that underscores the externalist source of affective states (Saarinen, 2020). It argues that one’s inner states and emotions are supported and regulated by contextual factors and other people (Colombetti & Krueger, 2015; Maiese, 2016; Saarinen, 2020). AS challenges the internalist hypothesis that emotions and moods appear exclusively on intra-person states and processes (Tirado-Morueta et al., 2021). Hence, it shifts from brain-centric descriptions of affectivity to those that endorse the dependency of affective states on social contexts and interactions (Saarinen, 2020). AS reflects different theories such as sociocultural theory, situatedness theory, and niche construction theory. Sociocultural theory and situatedness theory of mind respectively acknowledge the role of social context in one’s the development and mental activity (Robbins & Aydede, 2009; Vygotsky, 1978). However, niche construction theory concerns activities that one uses to modify his/her environment and affect self and others’ behaviors (Laland et al., 2016). These theories emphasize self-activeness in influencing one’s environment and building niches for how to think and feel (Saarinen, 2020).

Given the reciprocal impact that teachers and students have on each other, AS can reveal thoughts, feelings, and emotions in the class for a better understanding of each other, support each other, or create a sense of togetherness (Cornelius–White, 2007; Kalokerinos et al., 2015). In such a supportive context, educators can show their thoughts and positive parts of their personalities to each other (Oppermann & Lazarides, 2021; Wang et al., 2021). Teacher’s AS is one of the most well-known classroom factors that explicitly emphasizes the direct role of the teacher in classroom interactions (Pawlak et al., 2016). It refers to teachers’ attempts to modify and influence students’ affectivity by influencing their learning environment (Saarinen, 2020).

Students’ Academic Engagement

Emotional, cognitive, and behavioral engagements are three dimensions of academic engagement (Jang et al., 2010; Phung, 2017). The act of engagement has different consequences in interacting with the social context and answers the question of how students perceive their learning environments and how they satisfy their basic needs such as self-discipline, competence, and connection (Dao et al., 2019; Derakhshan, Doliński, et al., 2022; Richards et al., 2019). Academic engagement is one of the most important indicators of the quality of education, which functions as a psychological investment (Derakhshan, Fathi, et al., 2022; Martínez et al., 2019; Patall, 2013). It concerns students’ participation in the class and the existence of a positive and satisfactory state of mind with three dimensions energy, commitment, and fascination (Al-Hoorie, 2016; Wang et al., 2021). Another meaning of academic engagement is that students commit to the task or activity in such a way that they mobilize all their energy and internal resources to do it and will be able to insist on the task (Oppermann & Lazarides, 2021). The term is also defined as the interaction between attention and commitment (Froiland & Worrell, 2016). Students who get involved have a lot of attention and commitment because they value homework and activities (Hiver et al., 2021).

Students’ Psychological Well-Being

One of the factors related to language learners’ academic engagement is their basic psychological requirements. If these learners’ needs in the educational environment are met, their academic engagement will also increase (Burić & Macuka, 2018). This sense of well-being is obtainable when students are mentally and physically fit and have the motivation and energy to plan and strive for success (Dodd et al., 2021; Reeve & Tseng, 2011). These needs reflet SDT which vigorously assists one’s involvement in the environment, development of language skills, and staying healthy (Reyes et al., 2012).

Recently, the proponents of PP have taken a diverse approach to explaining students’ PWB (Burić & Macuka, 2018; Mikus & Teoh, 2021; Perera et al., 2018). They equate mental health with the affirmative function of psychology and conceptualize it in the notion of PWB (Mystkowska-Wiertelak, 2020). PP researchers pinpoint that the lack of disease is not enough for feeling fit. Conversely, they argue that having life satisfaction, adequate improvement, well-organized and affective communication with the world, optimistic liveliness, good association with the community, and affirmative development are the characteristics of a healthy student (Schenke et al., 2015). Research evidence offers that language learners, who are satisfied with their lives, receive enough stroke and credibility, and experience positive feelings have a high stage of PWB (Pishghadam et al., 2021; Shao et al., 2013). PWB includes one’s self-confidence and ability to see and accept strengths and weaknesses, form positive relationships with others, pursue desires, and act on personal principles that give meaning to life (Aubrey et al., 2020; Mikus & Teoh, 2021).

Empirical Studies

With the rise of PP and emotion-based education, several studies have empirically examined the mediating role of teachers’ and students’ psycho-emotional factors in their academic performance and engagement (Derakhshan, 2021; Wang et al., 2021). As for teacher AS, previous studies indicate that the construct is associated with superior success and less failure among students (Oppermann & Lazarides, 2021; Peng, 2020; Saarinen, 2020). It also reduces learners’ apathy and boredom, (Fathi et al., 2020; Pianta et al., 2012). AS can be implemented in L2 classes through building positive teacher-students interactions (Reeve & Tseng, 2011) and scaffolding L2 learners’ emotions by setting particular educational goals that echo their competence and values (Phung, 2017; Wang et al., 2021). Despite a mounting interest in language teaching and learning to scaffolding and affectivity, there is still little literature on teacher’s AS and its interplay with other critical constructs. One such construct is academic engagement, which has been found to create high levels of energy, classroom rapport, mental resilience, energy, or passion, a sense of commitment, complete concentration, and joyful absorption during the study (Derakhshan, Doliński, et al., 2022; Mystkowska-Wiertelak, 2020). (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4).

Research also shows that there is a positive relationship between academic engagement and academic grades, academic achievement, subject matter proficiency, successful handling of administrative barriers, and staying in educational settings (Aubrey et al., 2020; Mikus & Teoh, 2021). As a result, knowing the prerequisites of academic engagement is important to improve academic performance (Chow et al., 2017). Many psychological, social, environmental, educational, and cultural factors are predictive and effective in the engagement of students (Derakhshan, 2021; Kokkinos, 2007; Lee, 2017; Simbula, 2010). One of the most pivotal educational factors influencing students’ engagement and learning is teachers’ interaction and rapport with students (Perera et al., 2018; Wilson et al., 2010). These outcomes are only achieved in a favorable atmosphere, where teachers meet students’ psychological needs in the class using different scaffolding that ultimately generates higher well-being and vitality (Conley & You, 2009; Derakhshan et al., 2021; Perera et al., 2018).

Another area that academic engagement can positively influence is students’ PWB, which may be associated with depressive symptoms, violent behaviors, and social and psychological problems (Lee, 2017). To address such problems, teachers and educators must consider the psychological side of education (Simbula, 2010). Otherwise, all attempts, innovations, and reforms will lead to failure in academia (Friedman & Kern, 2014). Despite its importance, the interplay of academic engagement and PWB among L2 students has been limitedly conducted (Perera et al., 2018; Wilson et al., 2010). Besides, the role of other mediators like teacher scaffolding has been neglected in such an interaction (Proietti et al., 2021). This might be due to the absence of a model on the interplay of academic engagement, PWB, and AS. Teachers’ AS is highlighted because it is a metaphorical scaffolding that serves as an assistance to EFL learners’ language acquisition. However, scant literature exists on this construct in L2 education. To fill this gap, this study aimed to develop a model on the mediating role of teachers’ AS and support in the development of EFL students’ academic engagement and PWB. More specifically, the following research questions were sought out:

-

A)

How much variance in the perceived academic engagement can be predicted by Chinese EFL teachers’ affective support and learners’ psychological well-being?

-

B)

How much variance in perceived psychological well-being can be predicted by Chinese EFL teachers’ affective support and learners’ academic engagement?

Method

Participants

To minimize the sample selection bias, the present study adopted a random sampling technique to gather the data from the participants. As put by Dörnyei and Csizér (2012), random sampling is “a probability sampling method that provides a truly representative sample” (p. 81). This sampling led to the recruitment of a total of 1968 EFL students (1942 valid cases) with different academic qualifications (BA = 1441, MA = 421, PhD = 80) and proficiency levels (Elementary = 614, Intermediate = 1031, Upper-intermediate = 241, Advanced = 56) including both genders (male = 443, female = 1499). The age of the participants ranged from 16 to 50. They were selected from different colleges and universities of more than 20 majors across 77 cities in 22 provinces, 4 autonomous regions, 4 municipalities, and 1 special administrative region. Informed consent was given to participants in this research before they were selected via Wechat by means of Wenjuanxing. Further demographic information is demonstrated in Table 1.

Instruments

Teacher Affective Support (Scaffolding) Scale

To measure language learners’ perception of teachers’ AS and support, the scale developed by Romano et al. (2020) was adapted in this study. It included 14 items following a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Not at all true) to 5 (Very true). The scale had three components of “positive climate”, “teacher sensitivity”, and “adolescent perspective”. Concerning the reliability of the questionnaire, Romano et al. (2020) calculated Cronbach’s alpha scores for each component as a measure of internal consistency. The results indicated that positive climate, teacher sensitivity, and adolescent perspective had a reliability index of 0.74, 0.90, and 0.81, respectively that suggesting an acceptable validity. In this study, the reliability was re-examined and the results of internal consistency showed a reliability of 0.96 for the whole scale.

Academic Engagement Scale

The scale we used to assess students’ levels of academic engagement was adapted from the work by Reeve and Tseng (2011). It included four components of behavioral, affective, cognitive, and agentic engagement. The scale consisted of 19 items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1, representing “strongly disagree” to 5, representing “strongly agree”. With regard to the reliability index of the scale, it should be noted that the results of Cronbach’s alpha revealed reliability of 0.98.

Psychological Well-Being Questionnaire

The present research employed a modified version of Ryff’s (2007) 42-item PWBS to help the target sample group better understand the contents. It measures six aspects of well-being and happiness, namely “autonomy”, “environmental mastery”, “personal growth”, “positive relations with others”, “purpose in life”, and “self-acceptance”. The questionnaire uses a 7-point scale (1 = strongly agree; 7 = strongly disagree). 21 items are reversely scored so that higher scores indicate greater well-being. The reliability of the scale was also calculated by Cronbach’s alpha, whose results indicated an index of 0.89, which is a high level of reliability.

Data Collection Procedure

From early March to late May, 2022, our research team administered the national wide questionnaire survey with the help of our colleagues in China. There were two phases involved in our data collection. In the first phase, the questions were translated into Chinese to ensure the trustworthiness of the data collection and then the translated version was double-checked by two experts in applied linguistics. In doing so, we assumed that not all of the participants were adequately proficient in conceptualizing the questions in the questionnaire. Prior to distributing the subsequent scales, a consent form was sent to those participants in terms of ethical considerations (British Education Research Association, 2011) and then the e-version of the questionnaire was administered through WeChat (a popular communicative App in China) to 1968 participants, who demonstrated their agreement by completing the consent forms after they had been informed about the research purpose and instructions for the questionnaire. They were aware that the questionnaire was anonymous and that the data would be kept confidential. Moreover, the researchers offered some academic textbooks and resources related to L2 education to the participants as compensation for their precious time and consideration in the study. They completed it before their class, which allowed them to be more preoccupied with filling in the questionnaire. Each participant took approximately 15 min to complete the questionnaire. A total of 1968 students participated in this survey and after gleaning the collected data, 1942 valid cases were obtained.

Data Analysis

The data of this quantitative study were analyzed using different statistical techniques. First, descriptive statistics and inferential statistics were estimated using SPSS (v.25) and Amos software (v.24). After checking the assumptions, in both research questions, correlation coefficient, regression, Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), path analysis, and Chi-square test were used to analyze the data.

Results

The First Research Question

Before answering the research questions, which examined the variance in the perceived academic engagement of Chinese EFL teachers in light of affective support and learners’ PWB, descriptive statistics were calculated to present the central indicators and the dispersion of research variables. The results are shown in the following tables.

The descriptive statistics in Table 2 show that the mean variables of the AS, Academic Engagement, & PWB Questionnaire are equal to 63.34, 74.89, and 139.84 with deviations of 8.561, 13.660, and 27.874, respectively. Also, the Skewness and Kurtosis indices are in the range (2- and 2) for all except for Emotional Support and show that the distribution of variables is almost expected. One of the main assumptions of the Structural Equation Methods is the normality of the research variables. To check the normality of the research variables, the researcher used the Kolmogorov–Smirnov normality test, the results of which are as follows:

While the results show that the normality of the data is violated, it is acceptable for a sample size of more than 200. The next assumption of the Structural Equation Methods is the correlation of research variables. To investigate the correlation of research variables, the researcher used the Pearson test, the results of which are as follows:

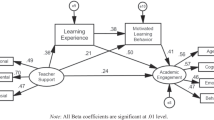

The correlation coefficients of Academic Engagement with AS and PWB are 0.655 and 0.160, respectively, which is significant at the level of 0.05. Also, the correlation coefficient of AS and PWB is equivalent to 0.066 and is significant at the level of 0.05. The path analysis method with Amos24 software is used to investigate the relationship between research variables. The research model is as follows:

The model was fitted in Amos 24 software. The results were obtained as follows.

According to the software output, Chi-square = 37,616.004, Degrees of freedom = 2697, and Probability level = 0.000, Chi-square test is significant (Sig = 0.000 < 0.05), so it can be concluded that there is a significant difference in the frequency of variables. (Tables 3, 4).

CMIN stands for the Chi-square value and is used to compare if the observed variables and expected results are statistically significant. In other words, CMIN indicates if the sample data and hypothetical model are an acceptable fit in the analysis. The value of interest here is the CMIN/DF for the default model and is interpreted as follows: If the CMIN/DF value is ≤ 3 it indicates an acceptable fit (Kline, 1998). The results of Table 5 show that the value for CMIN/DF is 3.947 which is less than 4.

RMSEA stands for Root Mean Square Error of Approximation and measures the difference between the observed covariance matrix per degree of freedom and the predicted covariance matrix (Chen, 2007). Root Mean Square Error of Approximation where values higher than 0.1 are considered poor, values between 0.08 and 0.1 are considered borderline, values ranging from 0.05 to 0.08 are considered acceptable, and values ≤ 0.05 are considered excellent (MacCallum et al, 1996). The results of Table 6 reveal that the RMSEA for the study is 0.081 which is considered as a borderline.

The results of Table 7 confirm that emotional support made contributions to variances in academic engagement and PWB scores. However, the AS variable made statistically significant contributions to variances in Academic Engagement scores.

The results of Table 8 present the Standardized Regression Weights for the variables. The results show AS included in the model contributed to the prediction of Academic Engagement and PWB scores. The results show that the largest statistically significant value is attributed to AS. This value indicates that AS uniquely explains about 73 percent of the variance in Academic Engagement. Moreover, it was found that AS explains 65 percent of the variance in PWB. Finally, PWB explained 56 percent of the variance in the Academic Engagement scores. (Table 9).

The Second Research Question

In order to answer this research question, which concerned the variance in the perceived PWB of Chinese EFL teachers in light of affective support and learners’ academic engagement, the path analysis method was used to investigate the relationship between variables. The extracted research model is as follows:

The model was then fitted into Amos 24 software. The results were obtained as follows.

According to the software output, Chi-square = 37,606.759, Degrees of freedom = 2697, and Probability level = 0.000, Chi-square test is significant (Sig = 0.000 < 0.05), so it can be concluded that there is a significant difference in the frequency of variables. However, the other values are not significant.

CMIN stands for the Chi-square value and is used to compare if the observed variables and expected results are statistically significant. In other words, CMIN indicates if the sample data and hypothetical model are an acceptable fit in the analysis. The value of interest here is the CMIN/DF for the default model and is interpreted as follows: If the CMIN/DF value is ≤ 3 it indicates an acceptable fit (Kline, 1998). The results of Table 10 show that the value for CMIN/DF is 3.944 that are less than 4.

RMSEA stands for Root Mean Square Error of Approximation and measures the difference between the observed covariance matrix per degree of freedom and the predicted covariance matrix (Chen, 2007). Root Mean Square Error of Approximation where values higher than 0.1 are considered poor, values between 0.08 and 0.1 are considered borderline, values ranging from 0.05 to 0.08 are considered acceptable, and values ≤ 0.05 are considered excellent (MacCallum et al, 1996). The results of Table 11 reveal that the RMSEA for the study is 0.081 which is considered a borderline.

The results of Table 11 confirm that all of the two variables made contributions to variances in PWB scores. However, the AS variable made statistically significant contributions to variances in PWB scores.

The results of Table 12 present the Standardized Regression Weights for the AS and Academic Engagement variables. The results show which of the variables included in the model contributed to the prediction of the PWB scores. The results show that the largest statistically significant value is attributed to AS. This value indicates that AS uniquely explains about 65 percent of the variance in PWB. The second variable is Academic Engagement which uniquely explains 56 percent of the variance in PWB.

Discussion

The present study investigated the impact of Chinese EFL teachers’ AS on students’ academic engagement and PWB. The research findings first showed that teacher AS was a directly positive predictor of EFL learners’ academic engagement and their PWB. Second, teachers’ AS and students’ academic engagement and PWB were directly related to each other. More particularly, the findings revealed that teachers’ AS had a statistically significant and positive effect on EFL learners’ academic engagement and PWB. It could positively predict both academic engagement and PWB by explaining about 73% and 65% of their variances.

The findings lend support to Henry and Thorsen (2018), who asserted that teachers’ AS has a positive effect on students’ academic engagement in a direct way. In other words, the better the teachers’ AS, the higher the students’ engagement in education (Zee & Koomen, 2016). Similarly, the findings are consistent with those obtained by Tirado-Morueta et al. (2021), who identified that teachers’ AS predicts students’ academic engagement in project-based learning cases. Moreover, the results echo those of Dörnyei and Ushioda (2021), who found that the favorable atmosphere of the classrooms and knowing how to communicate with learners and meet their psychological needs could help them learn actively and effectively. Therefore, the results are attributable to the learning atmosphere of Chinese EFL students that affected their sense of well-being and engagement. In other words, the educational context of the students may have been engaging to the participants making them experience sense of belongingness and involvement in classroom affairs (Chow et al., 2018). Another reason can be the close relationship between teachers and students in Chinese EFL contexts, which is accompanied by mutual respect and positive performance encouragement (Lee, 2020).

The results are in line with Perera et al. (2018), who argued that teachers’ AS and support have a strong correlation with language learners’ PWB (Perera et al., 2018). Hence, it can be stipulated that the more the teachers’ AS in the learning environment, along with acceptance, respect, support, and mutual trust, the more the students will feel free, competent, and connected (Burić & Macuka, 2018). Students feel more liberated when they feel that teachers respect them and can count on their help and support in the face of problems and issues (Lee et al., 2020). This sense of immediacy and strong rapport enables students to establish close relationships with others, which in turn improves and enhances their PWB (Ainsworth & Oldfield, 2019). Another justification for this finding can be the psych-emotional basis of both scaffolding and PWB, which may have triggered their positive and strong correlation and predictability. It seems that Chinese EFL teachers had been cognizant of students’ emotions and psycho-emotional status. Hence, they provided sufficient AS in the class to augment their pupils’ PWB, as a precondition for academic success.

Furthermore, the results demonstrated that PWB and academic engagement significantly predict each another. This is in tune with Peng (2020), who maintained that students’ psychological states considerably influence their academic engagement and satisfying their basic psychological needs promotes their engagement. In simple terms, when the psychological needs of students are met, they become more focused on their goals and more motivated, hence they become more active in their activities (Fredrickson et al., 2018). This is also consistent with the results of Martínez et al. (2019), who maintained that students’ academic engagement and performance are positively affected and boosted their psychological resources. Another justification for this finding can be the connection between students’ psychological needs and the deep structure of the human psyche, which provides the necessary energy to actively participate in the learning environment (Richards et al., 2019). In this study, it can be postulated that the Chinese EFL students were knowledgeable of their inner states and the connection among several psych-emotional factors that determine academic performance and engagement. They might have been already trained on the nexus of PWB and academic engagement, which can shape each other. When a student enjoys a high PWB, he/she is more likely to be academically engaged in the class. Conversely, when he/she has a high academic engagement level in classroom affairs, he/she is more likely to develop and promote PWB. In sum, the three variables concerned in this study had a strong interaction, which underscores the criticality of psych-emotional aspects of L2 education.

Conclusion and Implications

Based on the obtained findings, it can be asserted that EFL teachers’ AS is of paramount importance in generating PWB and academic engagement among their students. Given the connection among students’ psych-emotional factors, providing suitable AS can trigger other positive emotions in the classroom. This forms a cycle in which scaffolding leads to PWB and PWB leads to academic engagement, and academic engagement leads to other positive outcomes. This process may continue for as long as appropriate and professional AS is offered to the learners. As this study intended to highlight the role of emotions in L2 education, the results may be beneficial for EFL teachers in that they can use different scaffolding strategies to tap into their students’ affectivity and raise their academic performance. They can also realize the role of emotions in determining the sense of well-being and engagement in academia. EFL teacher trainers may also find this article momentous and propose training courses and workshops revolving around teacher scaffolding techniques and their impact on EFL students’ language learning. In such courses, practical ways of applying AS can be explicitly taught.

Moreover, researchers can use this study and examine other aspects of emotion and L2 education. For instance, they can try to compensate for the limitations of this study and conduct future studies with larger samples and through qualitative and mixed-methods research designs to be able to generalize the results to other learning environments. The generalizability scope of the study is also limited to EFL contexts and China. Hence future research is needed in other contexts. Future studies can also focus on demographic factors such as the students’ age, gender, proficiency level, and academic degrees and their impact on the interaction among AS, PWB, and academic engagement. Moreover, future studies can replicate this study or focus on different aspects of teachers’ affective support and learners’ PWB in the EFL contexts. Finally, cross-cultural and cross-disciplinary studies can be carried out in the future to examine variations in the three variables in light of context variations and major differences.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Acton, R., & Glasgow, P. (2015). Teacher wellbeing in neoliberal contexts: A review of the literature. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 40(8), 99–114. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2015v40n8.6

Ainsworth, S., & Oldfield, J. (2019). Quantifying teacher resilience: Context matters. Teaching and Teacher Education, 82, 117–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.03.012

Alavi, S. M., Dashtestani, R., & Mellati, M. (2021). Crisis and changes in learning behaviors: Technology-enhanced assessment in language learning contexts. Journal of Further and Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2021.1985977

Al-Hoorie, A. H. (2016). Unconscious motivation. Part II: Implicit attitudes and L2 achievement. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 6(4), 619–649. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2016.6.4.4

Al-Murtadha, M. (2019). Enhancing EFL learners’ willingness to communicate with visualization and goal-setting activities. TESOL Quarterly, 53(1), 133–157. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.474

Aubrey, S., King, J., & Almukhalid, H. (2020). Language learner engagement during speaking tasks: A longitudinal study. RELC Journal. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688220945418

Bowling, N. A., Eschleman, K. J., & Wang, Q. (2010). A meta-analytic examination of the relationship between job satisfaction and subjective wellbeing. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(4), 915–935. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317909X478557

British Education Research Association. (2011). Ethical guidelines for educational research. London: British Education Research Association. Available at: https://www.bera.ac.uk/publication/bera-ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-2011 (Accessed Sept. 2022).

Burić, I., & Macuka, I. (2018). Self-efficacy, emotions and work engagement among teachers: A two wave cross-lagged analysis. Journal of Happiness Studies, 19, 1917–1933. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017-9903-9

Burke-Smalley, L. A. (2018). Practice to research: Rapport as key to creating an effective learning environment. Management Teaching Review, 3(4), 354–360. https://doi.org/10.1177/2379298118766489

Carmeli, A., Yitzhak-Halevy, M., & Weisberg, J. (2009). The relationship between emotional intelligence and psychological wellbeing. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 24(1), 66–78. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940910922546

Chao, C. N. G., Chow, W. S. E., Forlin, C., & Ho, F. C. (2017). Improving teachers’ self-efficacy in applying teaching and learning strategies and classroom management to students with special education needs in Hong Kong. Teaching and Teacher Education, 66, 360–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.05.004

Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 14(3), 464–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701301834

Chen, J. C. C., & Kent, S. (2020). Task engagement, learner motivation and avatar identities of struggling English language learners in the 3D virtual world. System, 88, 102168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2019.102168

Chow, B. W., Chiu, H. T., & Wong, S. W. (2018). Anxiety in reading and listening english as a foreign language in Chinese undergraduate students. Language Teaching Research, 22(6), 719–738. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168817702159

Colombetti, G., & Krueger, J. (2015). Scaffoldings of the affective mind. Philosophical Psychology, 28(8), 1157–1176.

Conley, S., & You, S. (2009). Teacher role stress, satisfaction, commitment, and intentions to leave: A structural model. Psychological Reports, 105, 771–786. https://doi.org/10.2466/PR0.105.3.771-786

Cornelius-White, J. (2007). Learner-centered teacher–student relationships are effective: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 113–143. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298563

Crane, B. D. (2017). Teacher openness and prosocial motivation: Creating an environment where questions lead to engaged students. Management Teaching Review, 2(1), 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/2379298116673838

Dao, P., Nguyen, M. X. N. C., & Iwashita, N. (2019). Teachers’ perceptions of learner engagement in L2 classroom task-based interaction. The Language Learning Journal. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2019.1666908

Derakhshan, A. (2021). The predictability of Turkman students’ academic engagement through Persian language teachers’ non-verbal immediacy and credibility. Journal of Teaching Persian Speakers Other Languages, 10(21), 3–26. https://doi.org/10.30479/jtpsol.2021.14654.1506t

Derakhshan, A. (2022a). Revisiting research on positive psychology in second and foreign language education: Trends and directions. Language Related Research, 13(5), 1–43. https://doi.org/10.52547/LRR.13.5.1

Derakhshan, A. (2022b). The “5Cs” positive teacher interpersonal behaviors: Implications for learner empowerment and learning in an L2 Context. Springer.

Derakhshan, A., Coombe, C., Arabmofrad, A., & Taghizadeh, M. (2020). Investigating the effects of english language teachers’ professional identity and autonomy in their success. Issues in Language Teaching, 9(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.22054/ilt.2020.52263.496

Derakhshan, A., Kruk, M., Mehdizadeh, M., & Pawlak, M. (2021). Boredom in online classes in the Iranian EFL context: Sources and solutions. System. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2021.102556

Derakhshan, A., Dewaele, J. M., & Azari Noughabi, M. (2022). Modeling the contribution of resilience, well-being, and L2 grit to foreign language teaching enjoyment among Iranian english language teachers. System, 190, 102890. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2022.102890

Derakhshan, A., Doliński, D., Zhaleh, K., Janebi Enayat, M., & Fathi, J. (2022). Predictability of polish and Iranian student engagement in terms of teacher care and teacher-student rapport. System. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2022.102790

Derakhshan, A., Fathi, J., Pawlak, M., & Kruk,. (2022). Classroom social climate, growth language mindset, and student engagement: The mediating role of boredom in learning English as a foreign language. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2022.2099407

Derakhshan, A., Solhi, M., & Azari Noughabi, M. (2023). An investigation into the association between student-perceived affective teacher variables and students’ L2-grit. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2023.2212644.

Derakhshan, A., Wang, Y. L, Wang, Y. X, & Ortega-Martín, J. L. (2023). Towards innovative research approaches to investigating the role of emotional variables in promoting language teachers’ and learners’ mental health. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 25(7) 1–10. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2023.029877.

Dodd, R. H., Dadaczynski, K., Okan, O., McCaffery, K. J., & Pickles, K. (2021). Psychological wellbeing and academic experience of university students in Australia during COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(3), 866. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18030866

Dörnyei, Z., & Csizér, K. (2012). How to design and analyze surveys in second language acquisition research. In A. Mackey & S. M. Gass (Eds.), Research methods in second language acquisition: A practical guide (pp. 74–94). Blackwell.

Dörnyei, Z., & Ushioda, E. (2021). Teaching and researching motivation: New directions for language learning. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351006743

Eysenck, M. W., Derakshan, N., Santos, R., & Calvo, M. G. (2007). Anxiety and cognitive performance: Attentional control theory. Emotion, 7(2), 336–353. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.7.2.336

Fan, J., & Wang, Y. (2022). English as a foreign language teachers’ professional success in the Chinese context: The effects of well-being and emotion regulation. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.952503

Fathi, J., Derakhshan, A., & Saharkhiz Arabani, A. (2020). Investigating a structural model of self-efficacy, collective efficacy, and psychological well-being among Iranian EFL teachers. Iranian Journal of Applied Linguistics Studies, 12(1), 61–80. https://doi.org/10.22111/IJALS.2020.5725

Fredrickson, B. L., & Joiner, T. (2018). Reflections on positive emotions and upward spirals. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13(2), 194–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617692106

Freire, T., & Tavares, D. (2011). Influence of self-esteem and emotion regulation in subjective and psychological wellbeing of adolescents: Contributions to clinical psychology. Revista De Psiquiatria Clínica, 38(5), 184–188.

Friedman, H. S., & Kern, M. L. (2014). Personality, wellbeing, and health. Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 719–742. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115123

Froiland, J. M., & Worrell, F. C. (2016). Intrinsic motivation, learning goals, engagement, and achievement in a diverse high school. Psychology in the Schools, 53, 321–336. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21901

Greenier, V., Derakhshan, A., & Fathi, J. (2021). Emotion regulation and psychological well-being in teacher work engagement: A case of British and Iranian English language teachers. System. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102446

Guerra-Bustamante, J., Leon-del-Barco, B., Yuste-Tosina, R., Lopez-Ramos, V. M., & Mendo-Lazaro, S. (2019). Emotional intelligence and psychological wellbeing in adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(10), 1–12.

Han, Y., & Wang, Y. (2021). Investigating the correlation among Chinese EFL teachers’ self-efficacy, reflection, and work engagement. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 763234. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.763234

Henry, A., & Thorsen, C. (2018). Teacher-student relationships and L2 motivation. Modern Language Journal, 102(1), 218–241. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12446

Hiver, P., Al-Hoorie, A. H., Vitta, J. P., & Wu, J. (2021). Engagement in language learning: A systematic review of 20 years of research methods and definitions. Language Teaching Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688211001289

Huppert, F. (2009). Psychological well-being: Evidence regarding its causes and consequences. Applied Psychology: Health and WellBeing, 1(2), 137–164. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1758-0854.2009.01008.x

Jang, H., Reeve, J., Ryan, R. M., & Kim, A. (2009). Can self-determination theory explain what underlies the productive, satisfying learning experiences of collectivistically-oriented South Korean adolescents? Journal of Educational Psychology, 101, 644–661.

Jang, H., Reeve, J., & Deci, E. L. (2010). Engaging students in learning activities: It is not autonomy support or structure but autonomy support and structure. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102, 588–600. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019682

Kalokerinos, E. K., Greenaway, K. H., & Denson, T. F. (2015). Reappraisal but not suppression downregulates the experience of positive and negative emotion. Emotion, 15(3), 271–282. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000025

Kline, R. B. (1998). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Press.

Kokkinos, C. M. (2007). Job stressors, personality and burnout in primary school teachers. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77(1), 229–243.

Laland, K., Matthews, B., & Feldman, M. W. (2016). An introduction to niche construction theory. Evolutionary Ecology, 30(2), 191–202.

Lee, N. E. (2017). The part-time student experience: Its influence on student engagement, perceptions, and retention. Canadian Journal for the Study of Adult Education, 30(1), 1–18.

Lee, J. H. (2020). Relationships among students’ perceptions of native and non-native EFL teachers’ immediacy behaviors and credibility and students’ willingness to communicate in class. Oxford Review of Education, 46(2), 153–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2019.1642187

Lee, J. S., & Lee, K. (2020). Affective factors, virtual intercultural experiences, and L2 willingness to communicate in in-class, out-of-class, and digital settings. Language Teaching Research, 24(6), 813–833. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168819831408

Lee, Y. H., Richards, R., Andrew, K., & Washhburn, N. S. (2020). Emotional intelligence, job satisfaction, emotional exhaustion, and subjective wellbeing in high school athletic directors. Psychological Reports, 123(6), 2418–2440. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294119860254

MacCallum, R. C., Browne, M. W., & Sugawara, H. M. (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods, 1(2), 130–149.

Maiese, M. (2016). Affective scaffolds, expressive arts, and cognition. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 359. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00359

Martínez, I. M., Youssef-Morgan, C. M., Chambel, M. J., & Marques-Pinto, A. (2019). Antecedents of academic performance of university students: Academic engagement and psychological capital resources. Educational Psychology, 39(8), 1047–1067. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2019.1623382

Mikus, K., & Teoh, K. R. H. (2021). Psychological capital, future-oriented coping, and the wellbeing of secondary school teachers in Germany. Educational Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2021.1954601

Mystkowska-Wiertelak, A. (2020). Teachers’ accounts of learners’ engagement and disaffection in the language classroom. The Language Learning Journal. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2020.1800067

Naeem, K., Jawad, A., Rehman, S. U., & Javaid, U. (2021). Psychological wellbeing, job burnout and counterproductive work behavior among drivers of car hailing services in Pakistan: Moderating role of captains’ personality traits. European Online Journal of Natural and Social Sciences, 10(1), 19–33.

Oppermann, E., & Lazarides, R. (2021). Elementary school teachers’ self-efficacy, student perceived support and students’ mathematics interest. Teaching and Teacher Education, 103, 103351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103351

Paris, L. F. (2013). Reciprocal mentoring: Can it help prevent attrition for beginning teachers? Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 38(6), 136–158. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2013v38n6.5

Patall, E. A. (2013). Constructing motivation through choice, interest, and interestingness. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(2), 522–534. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030307

Pawlak, M., Mystkowska-Wiertelak, A., & Bielak, J. (2016). Investigating the nature of classroom willingness to communicate (WTC): A micro-perspective. Language Teaching Research, 20, 654–671. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168815609615

Peng, J. E. (2020). Teacher interaction strategies and situated willingness to communicate. ELT Journal, 74(3), 307–317. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccaa012

Perera, H. N., Granziera, H., & McIlveen, P. (2018). Profiles of teacher personality and relations with teacher self-efficacy, work engagement, and job satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 120, 171–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.08.034

Phung, L. (2017). Task preference, affective response, and engagement in L2 use in a US university context. Language Teaching Research, 21, 751–766. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168816683561

Pianta, R. C., Hamre, B. K., & Mintz, S. (2012). Classroom assessment scoring system secondary manual. Unpublished manuscript, Charlottesville.

Pishghadam, R., Derakhshan, A., Zhaleh, K., & Habeb Al-Obaydi, L. (2021). Students’ willingness to attend EFL classes with respect to teachers’ credibility, stroke, and success: A cross-cultural study of Iranian and Iraqi students’ perceptions. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01738-z

Proietti Ergün, A. L., & Dewaele, J.-M. (2021). Do wellbeing and resilience predict the foreign language teaching enjoyment of teachers of Italian? System. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2021.102506

Reeve, J., & Tseng, C. M. (2011). Agency as a fourth aspect of students’ engagement during learning activities. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36(4), 257–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2011.05.002

Reyes, M. R., Brackett, M. A., Rivers, S. E., White, M., & Salovey, P. (2012). Classroom emotional climate, student engagement, and academic achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(3), 700–712. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027268

Richards, K. A., Washburn, N. S., & Hemphill, M. A. (2019). Exploring the influence of perceived mattering, role stress, and emotional exhaustion on physical education teacher/coach job satisfaction. European Physical Education Review, 25(2), 389–408. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X17741402

Robbins, P., & Aydede, M. (2009). A short primer on situated learning. In P. Robbins & M. Aydede (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of situated cognition (pp. 3–10). Cambridge University Press.

Romano, L., Buonomo, I., Callea, A., Fiorilli, C., & Schenke, K. (2020). Teacher emotional support scale on Italian high school students: A contribution to the validation. The Open Psychology Journal. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874350102013010123

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Press.

Ryan, A. M., & Patrick, H. (2001). The classroom social environment and changes in adolescents’ motivation and engagement during middle school. American Educational Research Journal, 38(2), 437–460. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312038002437

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological wellbeing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069.

Ryff, C. D. (2014). Psychological wellbeing revisited: Advances in the science and practice of eudaimonia. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 83(1), 10–28. https://doi.org/10.1159/000353263

Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The structure of psychological wellbeing revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.719

Ryff, C. D., Almeida, D. M., Ayanian, J. S., Carr, D. S., Cleary, P. D., Coe, C., Williams, D. (2007). National Survey of Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS II), 2004–2006: Documentation of the Psychosocial Constructs and Composite Variables in MIDUS II Project 1. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research.

Saarinen, J. A. (2020). What can the concept of affective scaffolding do for us? Philosophical Psychology, 33(6), 820–839. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515089.2020.1761542

Sasaki, N., Watanabe, K., Imamura, K., Nishi, D., Karasawa, M., Kan, C., & Kawakami, N. (2020). Japanese version of the 42-item psychological wellbeing scale (PWBS-42): A validation study. BMC Psychology, 8(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-020-00441-1

Schenke, K., Lam, A. C., Conley, A. M., & Karabenick, S. A. (2015). Adolescents’ help seeking in mathematics classrooms: Relations between achievement and perceived classroom environmental influences over one school year. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 41, 133–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2015.01.003

Shakki, F. (2022). Iranian EFL students’ L2 engagement: The effects of teacher-student rapport and teacher support. Language Related Research, 13(3), 175–198.

Shao, K., Yu, W., & Ji, Z. (2013). An exploration of Chinese EFL students’ emotional intelligence and foreign language anxiety. The Modern Language Journal, 97(4), 917–929. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2013.12042.x

Simbula, S. (2010). Daily fluctuations in teachers’ wellbeing: A diary study using the job demands-resources model. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 23(5), 563–584. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615801003728273

Tang, Y., Tang, R., & Gross, J. (2019). Promoting psychological wellbeing through an evidence-based mindfulness training program. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 13, 237. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2019.00237

Tirado-Morueta, R., Ceada-Garrido, Y., Barragán, A. J., Enrique, J. M., & Andujar, J. M. (2021). The association of self-determination with student engagement moderated by teacher scaffolding in a project-based learning (PBL) case. Educational Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2021.2003185

Vesely, A. K., Saklofske, D. H., & Leschied, A. D. W. (2013). Teachers-the vital resource: The contribution of emotional intelligence to teacher efficacy and wellbeing. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 28(1), 71–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/0829573512468855

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Interaction between learning and development. Readings on the Development of Children, 23(3), 34–41.

Wang, Y., L., Derakhshan, A., & Zhang, L. J. (2021). Researching and practicing positive psychology in second/foreign language learning and teaching: The past, current status and future directions. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.731721

Wang, Y., Derakhshan, A., & Azari Noughabi, M. (2022). The interplay of EFL teachers’ immunity, work engagement, and psychological well-being: Evidence from four Asian countries. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2022.2092625

Wang, Y., Derakhshan, A., & Pan, Z. (2022). Positioning an agenda on a loving pedagogy in second language acquisition: Conceptualization, practice, and research. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 894190. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022

Wang, Y., Derakhshan, A., & Rahimpour, H. (2022). Developing resilience among Chinese and Iranian EFL teachers: A multi-dimensional cross-cultural study. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2022.2042540

Warr, B. P., Nielsen, K., & Psychology, W. (2018). Wellbeing and work performance abstract: Types of wellbeing types of work performance. 1–22.

Wellborn, J. G. (1992). Engaged and disaffected action: The conceptualization and measurement of motivation in the academic domain. Rochester: University of Rochester.

Wilson, J. H., Ryan, R. G., & Pugh, J. L. (2010). Professor-student rapport scale predicts student outcomes. Teaching of Psychology, 37(4), 246–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/00986283.2010.510976

Wolters, C. A. (2004). Advancing achievement goal theory: Using goal structures and goal orientations to predict students’ motivation, cognition, and achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96, 236–250. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.96.2.236

Xie, F., & Derakhshan, A. (2021). A conceptual review of positive teacher interpersonal communication behaviors in the instructional context. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.708490

Zee, M., & Koomen, H. M. Y. (2016). Teacher self-efficacy and its effects on classroom processes, student academic adjustment, and teaching wellbeing: A synthesis of 40 years of research. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 981–1015. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654315626801

Zhang, Z. (2020). Learner engagement and language learning: A narrative inquiry of a successful language learner. The Language Learning Journal, 50(3), 378–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2020.1786712

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Henan Provincial Education Department, Chinese Mainland. The author is grateful to the insightful comments suggested by the editor and the anonymous reviewers.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Teacher Education Project of Henan Provincial Education Department, entitled “Using Online Learning Resources to Promote English as a Foreign Language Teachers’ Professional Development in the Chinese Middle School Context” (Grant No.: 2022-JSJYYB-027).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Informed Consent

Informed consent letters were obtained from all the individual participants included in this study.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in the study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Pan, Z., Wang, Y. & Derakhshan, A. Unpacking Chinese EFL Students’ Academic Engagement and Psychological Well-Being: The Roles of Language Teachers’ Affective Scaffolding. J Psycholinguist Res 52, 1799–1819 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-023-09974-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-023-09974-z