Abstract

Understanding the microstructure and macrostructure of passages is important for reading comprehension. What cognitive-linguistic skills may contribute to understanding these two levels of structures has rarely been investigated. The present study examined whether some word-level and text-level cognitive-linguistic skills may contribute differently to the understanding of microstructure and macrostructure respectively. Seventy-nine Chinese elementary school children were tested on some cognitive-linguistic skills and literacy skills. It was found that word reading fluency and syntactic skills predicted significantly the understanding of microstructure of passages after controlling for age and IQ; while morphological awareness, syntactic skills, and discourse skills contributed significantly to understanding of macrostructure. These findings suggest that syntactic skills facilitate children’s access of meaning from grammatical structures, which is a fundamental process in gaining text meaning at any level of reading comprehension. Discourse skills also allow readers to understand the cohesive interlinks within and between sentences and is important for a macro level of passage understanding.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Cognitive-linguistic skills that are important for word decoding and reading comprehension have been studied widely in recent decades. Different cognitive-linguistic skills have been proposed and examined in explaining how one learns to read and spell words in both alphabetic (e.g., English) (e.g., Bryant and Goswami 1987; Cunningham and Stanovich 1991; Leong 1999; Rego and Bryant 1993; Siegel 2008; Tunmer and Hoover 1992) and non-alphabetic orthographies (e.g., Chinese) (e.g., Packard et al. 2006; Ho and Bryant 1997; Ho et al. 2003a, b; Ku and Anderson 2003; McBride-Chang and Ho 2005; Yeung et al. 2011). In more transparent alphabetic scripts with consistent grapheme–phoneme correspondences, having adequate phonological skills allow children to learn and access their lexicons quickly, or automatically, when hearing or reading the target words (Adams 1990; Bryant and Goswami 1987). On the other hand, children may rely more on orthographic skills in less transparent scripts like Chinese, in which the relationship between grapheme and phoneme is less reliable (Cunningham and Stanovich 1991; Shu et al. 2000). Similar to the role of phonological skills, orthographic skills allow children to quickly access lexicons by detecting the orthographic regularities of words (Goswami 1999). Through familiarization with these regularities, the memory load for remembering a word’s spelling is reduced (Tan et al. 2005). At the same time, efficient word retrieval, i.e., reading fluency, may also be fundamental for literacy success (Kirby et al. 2008; Schweizer 1998). Furthermore, children who are aware of the derivational rules can make intelligent guesses as to the meaning of different combinations of morphemes (Arnbak and Elbro 2000; McBride-Chang et al. 2003). Children gradually stop treating words as isolated. Inflectional rules provide a shortcut to accessing the meaning of words with particular prefixes or suffixes (Mahony et al. 2000). In other words, morphological skills enable children to manage a large number of lexicons in a systematic network. Having some understanding about what cognitive-linguistic skills contribute to word learning, researchers next ask what other skills may be important beyond word-level processing.

Syntactic Skills and Discourse Skills

Words build a sentence and sentences build a passage. Text comprehension may be considered as a word-text integration process. Words are connected in specific orders to form sentences. Meaning is not only delivered by the words in a sentence, but also their arrangement, i.e., syntax (Sterelny 1990). Syntactic skills are therefore an important basic skill for understanding a sentence or a passage (Chik et al. 2012a). Supporting evidences have showing that syntactic skills make a significant unique contribution to children’s reading comprehension performance in both alphabetic and non-alphabetic orthographies (e.g., Chen et al. 1993; Chik et al. 2012a; Muter et al. 2004; Nation and Snowling 2004). One common measure is to ask participants to construct grammatically correct sentences by arranging randomly presented sets of words or phrases (Chik et al. 2012a).

Similarly, a passage is not a mere combination of sentences; the sentences should be arranged in a meaningful way to form a coherent passage. Discourse emphasizes the way that sentences are connected so as to deliver a coherent set of ideas within a passage (i.e., global coherence) (Bishop and Snowling 2004; Chik et al. 2012b). Discourse skills, in the context of reading comprehension, are regarded as the ability to detect the connectedness between sentences, which enhances passage-reading efficiency (Bishop and Snowling 2004; Cain and Oakhill 1996). Discourse skills also help integrate the text and context in order to accomplish a sense of integration and coherence (Cook 1989). Readers with mature discourse skills can therefore simultaneously process the sentence’s meaning and keep checking its compatibility with the ideas that the previous sentences have set out (Perfetti et al. 2005).

One effective way to assess discourse skills is to ask participants to rearrange sentences to form a coherent paragraph (Chik et al. 2012b). This is similar to a word-order task. A key difference, however, is that a discourse skills task focuses on participants’ awareness and understanding of the connectedness between sentences (i.e., linguistic cohesion) (Cain 2003; Shapiro and Hudson 1991). Though the sentences may use different syntactic structures, when placed in the correct order, together they should deliver an integrated and coherent theme. As discourse markers (e.g., connectives) enable the reader to understand and generate expectations of what will be read in the text following (Perfetti et al. 2005), discourse skills have been found to be significant facilitators in reading comprehension (Camiciottoli 2003; Chung 2000; Geva 1992; Ozono 2002; Ozono and Ito 2003). Participants with good discourse skills can make use of the discourse markers and keep track of a passage’s central theme while reading (Crismore 1989).

Are syntactic and discourse skills important for reading Chinese? Chinese grammar is noninflectional and lacks the grammatical devices of inflections and function words (Li et al. 2002). Word order is often regarded as the most important syntactic device in Chinese (Chang 1992; Chao 1968). Children’s word order skills was found to be a strong correlate of Chinese reading comprehension in early elementary grades (e.g., Chik et al. 2012a; Yeung et al. 2013). However, the study by Chik et al. (2012b) showed that morphosyntax, a more advanced syntactic skills, instead of word order skills, accounted for significant amount of unique variance in reading comprehension among children in senior elementary grades. Discourse skills were also found to be a significant predictor of Chinese reading comprehension for children in all grades in their study. These findings support the important role of syntactic and discourse skills for reading comprehension but how these skills may contribute to different levels of comprehension is rarely examined.

Microstructure and Macrostructure

Reading comprehension performance usually refers to how well a reader can understand the content of a given passage. Readers’ understanding may be further divided into two levels: an understanding of microstructure and macrostructure (Kintsch and Kintsch 2005). Similar to the conceptual differentiation between top-down and bottom-up processing, it is difficult, if not impossible, to separate the role of microstructural and macrostructural understanding in reading comprehension which is a highly integrative cognitive output. However, understanding of microstructure versus macrostructure does serve different functions for reading comprehension. For example, unlike the macrostructure that bears an implicit nature, the microstructure of a passage usually consists of information that is explicitly presented in the passage (Kintsch 1994; Kintsch and Kintsch 2005). It shares some features with the mental model in which only the presented premises are used for constructing the model and generating possible conclusions (Kintsch and Kintsch 2005). An understanding of microstructure enables the reader to comprehend the events explicitly described in a passage, but is less likely to bring out implications or the underlying meaning of the passage. For example, in a descriptive passage that states “John is going to Mount Everest”, the microstructure allows the reader to know where John is going. Nevertheless whether John would have an adventurous experience is beyond the scope of microstructural understanding, and only understanding of the macrostructure may help. Generally speaking, both types of understanding are triggered in parallel in the process of reading comprehension. Unlike microstructure, the reader’s own experiences greatly affect how the macrostructure of a passage is developed. Macrostructure can be understood as a broad network in which the information being read from the passage is assimilated into the reader’s existing knowledge (Johnson-Laird 1983; Kintsch 1994; Kintsch and Kintsch 2005; Leong et al. 2008). The newly read information integrates with the reader’s existing knowledge to create a situational model. Information in this situational model comes from words in the passage, inferences based on the text, and the reader’s existing relevant knowledge (Verhoeven and Perfetti 2008). By integrating information from different sources, the reader may generate a coherent understanding of the passage (McNamara et al. 1991; Sadoski and Paivio 2007). In other words, readers are not passively taking in the information from a passage, but actively interpreting and creating meanings for the information that fits best with their existing knowledge. Text comprehension can therefore be understood as an interaction between bottom-up (i.e., decoding words to lexicons) and top-down processing (i.e., processing sentences based on certain expectations) (Sadoski 1999; Verhoeven and Perfetti 2008).

The conceptual underpinning of macrostructure is highly similar to schematic processing (Samuels 2005). The ease of integrating newly acquired information is determined by its compatibility with the existing schema, or knowledge. Information with high compatibility can be assimilated easily, whereas incompatible information is usually harder to understand. A classic example was provided by Bransford and Johnson (1972). Participants were asked to read a passage describing an action. Without giving the title of the passage, participants had great difficulty in remembering and understanding the description. In other words, the information carried in the passage did not integrate well with the participants’ existing knowledge. When the passage’s title (laundry) was given to the participants before reading, significant improvement in both understanding and retention resulted. Similarly, sentences that violate the principle of referential continuity are harder to remember than those that do not (Ehrlich and Johnson-Laird 1982). The results on spatial referential continuity also extend to the study of temporal order. It has been found that if sentences are arranged into an order that fits well with the actual sequence of the events described, the text is easier to understand than when the order of the sentences violates the original sequence (Brewer 1987; Brewer and Ohtsuka 1988). This finding is corroborated by daily observation: stories organized chronologically are easier to understand than stories in reverse chronology. Based on the above review, macrostructure is considered an important element of reading comprehension.

Measuring Reading Comprehension

The typical way of assessing a reader’s understanding of a passage is to measure how well he/she could answer questions concerning the content of the given paragraphs (e.g., Chen et al. 1993; Fletcher 2006; Leong and Ho 2008; Leong et al. 2008). These questions are regarded as a means of assessing readers’ general understanding. This kind of question setting usually does not differentiate between microstructural and macrostructural understanding. Some studies, however, have tried to capture the essence of this differentiation. Participants in these studies were required to answer different types of questions after reading several passages (Deane et al. 2006; Hannon and Daneman 1998; Leong et al. 2008). Microstructural understanding was usually captured by questions which readers could answer based on propositions explicitly stated in the passages, i.e., literal inferencing questions. This type of questions did not require the reader to integrate what is read (now) and what is known (before). The reader’s macrostructural understanding was assessed by questions that focused more on their understanding of the themes or implications of the passages, i.e., elaboration inferencing questions (Kintsch and Kintsch 2005; Samuels 2005). These questions are used to assess the reader’s integration and inferencing ability by examining whether he or she can generate possible expectations based on the passage and the corresponding implications (Johnson-Laird 1983; McNamara et al. 1991). Some studies further suggest that performance in responding to the elaboration inferencing questions may better reflect reading comprehension skills (Kintsch and Kintsch 2005). Since understanding of microstructure and macrostructure has rarely been examined in the context of reading Chinese, the present study set out to examine its relationship to reading comprehension and to some cognitive-linguistic skills.

The Present Study

In examining the potential contributions of different cognitive-linguistic skills to microstructural and macrostructural understanding of a passage, we have three expectations. First, word-level skills are expected to be important for microstructural understanding. Efficient retrieval of word sound and meaning in reading fluency may help a reader to answer literal inferencing questions which require basic understanding of text information. Similarly, orthographic and morphological skills are expected to predict how well people answer questions concerning microstructural understanding, because it has been established that these two types of skills have significant roles at word-level processing (Leong 2002; Leong and Ho 2008). Word-level processing is always necessary before any level of text comprehension is possible.

Second, syntactic skills which facilitate readers to get meaning from sentences are basic to all levels of text understanding (Chen 1996; Chik et al. 2012a, b). They are expected to play an important role for both a basic and an integrative level of understanding of passages.

Third, we expect that discourse skills are particularly important for understanding macrostructure. Elaboration inferencing questions, as a means of measuring macrostructural understanding, require readers to integrate different ideas of a passage into their existing knowledge in order to understand the thematic ideas conveyed. This integration requires an awareness of the connectives, or the discourse markers, between the sentences. In comparison, literal inferencing questions put less stress on readers’ integrative power. Readers may not need to be highly sensitive to the discourse markers between the sentences throughout a passage and still be able to answer the literal inferencing questions correctly, based on the situational model. In other words, the present study expects that word-level cognitive-linguistic skills are significant predictors of microstructure understanding, whereas discourse skills mainly predict the performance of macrostructure understanding, and syntactic skills may predict both.

Multiple-choice (MC) questions and open-ended (OE) questions are commonly adopted in studies of reading comprehension. Both have their merits and demerits. In order to minimize the effect of subjective judgement and ensure an objectivity of the assessment, all the measures in the present study were not of an open-ended answer protocol. On the other hand, we are aware that traditional MC questions may not be as delicate as OE questions in assessing reading comprehension (Daneman and Hannon 2001). To ensure different levels of reading comprehension was measured accurately in the present study, response items of the MC questions in the reading comprehension task were carefully constructed so that each incorrect answer of a question contained specific irrelevant information which differentiated from the correct answer. In other words, selection of a correct answer may reflect more reliably a participant’s understanding of the passage. Details of test construction will be described below.

Method

Participants

The participants were 79 Chinese primary school students recruited from one mainstream school in Hong Kong, with 42 boys and 37 girls. Their mean age was 8 years and 1 month. All were of normal intelligence (IQ 80 or above), with a mean IQ of 110. The children were carefully screened to ensure that they had sufficient learning opportunity (for instance, new immigrants were excluded) and they did not have any suspected brain damage, uncorrected sensory impairment, or serious emotional or behavioral problems. All the children included in this study were from families who spoke Cantonese as their first-language; Cantonese was the medium of instruction in their school.

Materials and Procedures

The participants were administered a nonverbal intelligence test, one reading comprehension task, three tasks on word-level reading-related skills (homophone awareness, radical function, and one-min word reading), and two tasks on text-level reading-related skills (word order and discourse skills). With the exception of the reading fluency task, all tasks were administered in groups. The homophone awareness, radical function, and word order tasks were administered using a computerized testing platform rather than by individual experimenters. Table 1 shows the means and standard deviations of the various measures.

Raven’s Standard Progressive Matrices

The participants’ nonverbal intelligence was assessed by the Raven’s Standard Progressive Matrices. This is a standardized test with five sets of 12 items each. Each item consists of a visual target matrix with a missing piece. The children were required to choose the best piece to complete the target matrix from six to eight alternatives. Scoring procedures were based on the local norm established by the Education Department of The Hong Kong Government in 1986.

Reading Comprehension

In this task, the children were asked to read a total of six narrative or expository passages in silence. The passages varied in length between 147 and 180 Chinese characters. To ensure that the text difficulty was appropriate, the vocabularies used were selected from early grades according to The Hong Kong Corpus of Primary School Chinese by Leung and Lee (2002). The children were asked to answer three to four multiple-choice questions on each passage. The incorrect answer options contained words taken from the passages but were irrelevant to the questions or not addressing the main issues of the questions. A sample passage with four practice questions was presented to the participants before the test. A total of 18 questions were given with half on testing microstructure understanding and half on macrostructure. One point was given for a correct answer to each multiple-choice question.

Homophone Awareness

The homophone task was used to measure the children’s morphological awareness. The format and procedures of this task were similar to those in the study by McBride-Chang et al. (2003). In each item of this task, the children heard three two-syllable Chinese words presented to them by a computerized recording, all of which had an identical syllable in the same position (either first or second in a two-character word). For example, the words

[naam4] [tsi3] (meaning “male washroom”),

[naam4] [dzai2] (meaning “young boy”), and

[naam4] [gik9] (meaning “south pole”), share the same syllable [naam4], but it bears the meaning of “male” in the first two words, and means “south” in the third word. Two trial items were presented to the participants before the 49 test items. One point was given for each correct answer up to a maximum possible score of 49.

Radical Function

This task was administered to measure the children’s orthographic skills, and in particular their awareness of the function of semantic radicals and their skill in applying this knowledge to complete unknown written words. The task consisted of 24 items, each comprising a sentence and three choices of semantic radicals presented visually on a screen, and audibly at least once by the computerized testing system. In each sentence, a target character was presented with its semantic radical omitted. The children were asked to select a suitable semantic radical from three choices to complete the target character by making use of the meaning of the sentence. Two trial items were presented to the participants before the 24 test items. One point was given for each correct answer.

One-Minute Word Reading

This task was used to measure reading fluency. The children were asked to read as many Chinese two-character words as they could, from a list of 100 words, in 1 min. The number of correct words read was recorded for each student.

Word Order Skills

This task was used to measure the children’s knowledge of some basic Chinese sentence structure rules (e.g., subject–verb–object, subject–verb–verb, and special sentence types, such as using “ba”

, etc.). There was a total of 53 items and the children were asked to arrange three to seven sentence fragments, visually presented on a computer screen, into a syntactically correct sentence. The mean length of the sentences was 13 Chinese characters. One point was given for each correctly ordered sentence.

Discourse Skills

This task was intended to measure the children’s skills in drawing inferences between sentences that together form a coherent and meaningful discourse. In each of the nine items, the children were asked to arrange three to five sentences into a coherent and meaningful discourse, which was either a narration of events or an elaboration of procedures or facts. Two practice items were given to the participants before the formal testing. One point, two points, and three points were given for correctly ordered three-, four-, and five-sentence items, respectively. The maximum score for this task was 17 points.

Example :

1.

Then, pick up [the] glass [of water].

2.

Finally, cover [it] with a lid.

3.

First, pour water into [a] glass.

Answer: (3) (1) (2)

Results

Table 2 shows that all of the partial correlation coefficients among the various measures in the present study, after controlling for age and IQ, were statistically significant (all \(\hbox {rs} > .30\), all \(\hbox {ps} < .05\)). This result showed that the various cognitive-linguistic skills and reading comprehension were highly associated. Two sets of regression analyses were conducted separately to identify the significant predictors of reading comprehension on microstructure and macrostructure respectively. In each set of analysis, age and IQ were entered into the equation first as control variables. The three word-level cognitive-linguistic skills were then entered in step two, followed by the two text-level skills in the final step.

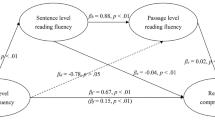

Table 3 summarizes the results of these regression analyses. Age and IQ accounted for 14.8 % of variance of the microstructure understanding in Chinese reading comprehension. The cognitive-linguistic predictors explained an additional 51.3 % [F(6, 72) \(=\) 23.36, \(p<0.001\)]. Among the five predictors, one-min word reading (\(\upbeta >0.19\), all \(p<0.05\)) and word order skills \((\upbeta >0.19, p<0.05)\) had significant unique contributions to microstructure understanding in reading Chinese passages. Similarly, age and IQ accounted for 14.9 % of variance of the macrostructure understanding in Chinese reading comprehension. The cognitive-linguistic predictors explained an additional 49.3 % of the variance [F(7, 71) \(=\) 18.22, \(p<0.001\)]. Among these predictors, homophone awareness, word order skills, and discourse skills (all \(\upbeta s>0.21\), all \(ps<0.05\)) had significant unique contributions to macrostructure understanding in reading Chinese passages.

Discussion

Contributions of Reading Fluency and Syntactic Skills to Understanding of Microstructure

To reiterate, the aim of the present study was to investigate the roles of different cognitive-linguistic skills for understanding the microstructure and macrostructure of Chinese passages. The present findings from the regression analyses showed that word reading fluency and syntactic skills were significant predictors of microstructural understanding when age, IQ, and other cognitive-linguistic skills were controlled. To recap, microstructural understanding refers to a general understanding of the information that is explicitly expressed in a passage. The one-min word reading task measured how well a child recognized words accurately and quickly within a time limit. Word retrieval fluency suggests rapid access to word meaning and this ability undoubtedly facilitates a basic level of text understanding. Apart from word meaning, how words are arranged syntactically and meaningfully in sentences is also essential for basic level of text understanding. Syntactic skills, as measured by word order, appear to be a strong predictor of the literal level of text understanding in Chinese. This finding is consistent with past literature about the significant role of syntactic skills on Chinese reading comprehension (e.g., Chik et al. 2012a; Yeung et al. 2013). At the word level, awareness of grammatical rules and structures helps a reader to predict the meaning of some unfamiliar words in a text context. This would enhance the mastery of basic information in text reading.

To our surprise, orthographic skills and morphological awareness did not predict understanding of microstructure. Since these two cognitive-linguistic skills have been found to be important for word reading, it is possible that the one-min word reading task has taken up some of the shared variance. This suggestion is supported by the significant correlation among these three measures.

Contributions of Morphological Skills, Syntactic Skills, and Discourse Skills to Understanding of Macrostructure

Apart from contributing to understanding of microstructure, syntactic skills also contribute significantly to macrostructure understanding. Macrostructure understanding requires a reader to make inferences based on the text and his or her own experiences in order to access the themes or underlying meaning of a passage. Knowledge of grammatical structures may help a reader to understand the meaning of a sentence more precisely, especially those involve connective markers. These would help a reader to develop a cohesive schema of a passage.

Discourse skills have been shown to be important for reading comprehension in past studies (e.g., Chik et al. 2012a, b). However, the present study may be the first one to show the unique role of discourse skills for reading comprehension in developing understanding of the macrostructure of a passage. Discourse skills allow readers to understand the cohesive interlinks within and between sentences (Khatib 2011; Brown and Yule 1989). Readers are therefore able to appreciate the underlying meaning that may not be explicitly expressed in a passage (Brewer 1987). Unlike microstructural understanding, understanding the macrostructure of a passage requires the integration of the text ideas with the reader’s own knowledge to achieve a coherent and thorough understanding. This kind of integration allows the reader to access the thematic ideas and underlying propositions of a passage. Compared to literal inferencing questions, for which answers can be found directly from the text, elaboration inferencing questions are more concerned with comprehension of the themes and meaning that can only be obtained when readers are able to integrate the text with their own knowledge. Therefore, in answering elaboration inferencing questions on macrostructural understanding of a passage, knowledge of discourse structure is essential for a reader to get at the thematic or underlying meaning of the text.

Morphological skills were found to predict significantly the understanding of macrostructure in the present study. Given the abundance of homophones and reliance of word compounding in Chinese, morphological awareness helps a reader to understand word meaning more precisely and predict meaning of unfamiliar words in text (Chow and Chow 2005; Shu and Anderson 1997). This may facilitate a reader to get at the main points of paragraphs, and to make inferences based on understanding of some important key words.

Conclusion

Text understanding is the ultimate goal of learning to read. There are at least two levels of passage understanding, namely understanding the microstructure and macrostructure. The present findings show that syntactic skills, which help extracting meaning from sentence structures, were a significant predictor of both microstructural and macrostructural understanding. Discourse skills, which emphasize the ability to integrate propositions in order to access the thematic meaning of a passage, and morphological skills were found to be contributive to macrostructural understanding. Both levels of understanding are essential for reading comprehension and they may be developmental in progression. Understanding the literal meaning of text is fundamental for integrative and elaborative understanding of the main ideas of a passage. The present findings suggest that strengthening the syntactic and discourse skills of students may be a way to improve their reading comprehension, especially at the integrative level of comprehension.

References

Adams, M. J. (1990). Beginning to read: Thinking and learning about print. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Arnbak, E., & Elbro, C. (2000). The effect of morphological awareness trainig on the reading and spelling skills of young dyslexics. Scandinavian Journal of educational Research, 44(3), 229–251.

Bishop, D. V. M., & Snowling, M. J. (2004). Developmental dyslexia and specific language impairment: Same or different? Psychological Bulletin, 130(6), 858–886.

Bransford, J. D., & Johnson, M. K. (1972). Contextual prerequisites for understanding: Some investigations of comprehension and recall. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 11, 717–726.

Brewer, W. F. (1987). Schemas versus mental models in human memory. In P. Morris (Ed.), Modelling cognition (pp. 187–197). Chichester: Wiley.

Brewer, W. F., & Ohtsuka, K. (1988). Story structure and reader affect in American and Hungarian short stories. In C. Martindale (Ed.), Psychological approaches to the study of literary narratives (pp. 133–158). Hamburg: Buske.

Brown, G., & Yule, G. (1989). Discourse analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bryant, P. E., & Goswami, U. (1987). Beyond grapheme–phoneme correspondence. Cahiers de Psychologie Cognitive, 7, 439–443.

Cain, K. (2003). Text comprehension and its relation to coherence and cohesion in children’s fictional narratives. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 21, 335–351.

Cain, K., & Oakhill, J. (1996). The nature of the relationship between comprehension skill an teh ability to tell a story. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 14, 187–201.

Camiciottoli, B. C. (2003). Metadiscourse and ESP reading comprehension: An exploratory study. Reading in a Foreign Language, 15(1), 15–33.

Chang, H. W. (1992). The acquisition of Chinese syntax. In H. C. Chen & O. J. L. Tzeng (Eds.), Language processing in Chinese (pp. 277–311). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Chao, Y. R. (1968). A grammar of spoken Chinese. Oakland, USA: University of California Press.

Chen, H. C. (1996). Chinese reading and comprehension: A cognitive psychology perspective. In M. H. Bond (Ed.), The handbook of Chinese psychology (pp. 43–62). Hong Kong: Oxford university Press (China) Ltd.

Chen, M. J., Lau, L. L., & Yung, Y. F. (1993). Development of component skills in reading Chinese. International Journal of Psychology, 28(4), 481–507.

Chik, P. P.-M., Ho, C. S.-H., Yeung, P.-S., Luan, H., Lo, L.-Y., Chan, D. W.-O., et al. (2012a). Syntactic skills in sentence reading comprehension among Chinese elementary school children. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 25(3), 679–699.

Chik, P. P.-M., Ho, C. S.-H., Yeung, P.-S., Wong, Y. K., Chan, D. W.-O., Chung, K. K.-H., et al. (2012b). Contribution of discourse and morphosyntax skills to reading comprehension in Chinese dyslexic and typically developing children. Annuals of Dyslexia, 62(1), 1–18.

Chow, B. W. Y., & Chow, C. S. L. (2005). The development of morphological awareness: Analysis of children’s responses on the Chinese morphological construction task. Journal of Psychology in Chinese Societies, 6(2), 145–160.

Chung, J. S. L. (2000). Signals and reading comprehension: Theory and practice. System, 28(2), 247–259.

Cook, G. (1989). Discourse. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Crismore, A. (1989). Talking with readers: Metadiscourse as rhetorical act. New York: Peter Lang Publishers.

Cunningham, A. E., & Stanovich, K. E. (1991). Tracking the unique effects of print exposure in children: Associations with vocabulary, general knowledge, and spelling. Journal of Educational Psychology, 83, 264–274.

Daneman, M., & Hannon, B. (2001). Using working memory theory to investigate the construct validity of multiple-choice reading comprehension tests such as SAT. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 11, 175–193.

Deane, P., Sheehan, k M., Sabatini, J., Futagi, Y., & Kostin, I. (2006). Difference in text structure and its implications for assessment of struggling readers. Scientific Studies of Reading, 10, 257–275.

Ehrlich, K., & Johnson-Laird, P. N. (1982). Spatial descriptions and referential continuity. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 21, 296–306.

Fletcher, J. M. (2006). Measuring reading comprehension. Scientific Studies of Reading, 10(3), 323–330.

Geva, E. (1992). Reading comprehension in a second language: The role of conjunctions. TESL Canada Journal, 1, 85–96.

Goswami, U. (1999). The relationship between phonological awareness and orthographic representation in different orthographies. In M. Harris & G. Hatano (Eds.), Learning to read and write: A cross-linguistic perspective (pp. 134–172). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hannon, B., & Daneman, M. (1998). Facilitating knowledge-based inferences in less-skilled readers. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 23, 149–172.

Ho, C. S. H., & Bryant, P. (1997). Development of phonological awareness of Chinese children in Hong Kong. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 26(1), 109–126.

Ho, C. S. H., Ng, T. T., & Ng, W. K. (2003). A “radical” approach to reading development in Chinese: The role of semantic radicals and phonetic radicals. Journal of Literacy Research, 35(3), 849–878.

Ho, C. S. H., Yau, P. W. Y., & Au, A. (2003). Development of orthographic knowledge and its relationship with reading and spelling among Chinese kindergarten and primary school children. In C. McBride-Chang & H. C. Chen (Eds.), Reading development in Chinese children (pp. 51–71). New Haven: Greenwood.

Johnson-Laird, P. N. (1983). Mental models: Towards a cognitive science of language, inference, and consciousness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Khatib, M. (2011). Comprehension of discourse markers and reading comprehension. English Language Teaching, 4(3), 243–250.

Kintsch, W. (1994). Text comprehension, memory, and learning. American Psychologist, 49, 294–303.

Kintsch, W., & Kintsch, E. (2005). Comprehension. In S. G. Paris & S. A. Stahl (Eds.), Children’s reading comprehension and assessment (pp. 71–92). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Kirby, J. R., Desrochers, A., Roth, L., & Lai, S. S. V. (2008). Longitudinal predictors of word reading development. Canadian Psychology, 49(2), 103–110.

Ku, Y. M., & Anderson, R. C. (2003). Development of morphological awareness in Chinese and English. Reading and Writing, 16(5), 399–422.

Leong, C. K. (1999). Phonological coding and children’s spelling. Annals of Dyslexia, 49, 195–220.

Leong, C. (2002). Segmental analysis and reading in chinese. Cognitive neuroscience studies of the chinese language (pp. 227–246). Aberdeen: Hong Kong University Press.

Leong, C. K., & Ho, M. K. (2008). The role of lexical knowledge and related linguistic components in typical and poor language comprehenders of Chinese. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 21, 559–586.

Leong, C. K., Tse, S. K., Loh, E. K. Y., & Hau, K. T. (2008). Text comprehension in Chinese children: Relative contribution of verbal working memory, pseudoword reading, rapid automatized nam and onset-rime phonological segmentation. Education Psychology, 100, 135–149.

Leung, M. T., & Lee, A. (2002). The Hong Kong corpus of primary school Chinese. Paper presented at the 9th meeting of the international clinical phonetics and linguistics association. Hong Kong.

Li, W., Anderson, R. C., Nagy, W., & Zhang, H. (2002). Facets of metalinguistic awareness that contribute to Chinese literacy. In W. Li, J. S. Gaffney, & J. L. Packard (Eds.), Chinese children’s reading acquisition: Theoretical and pedagogical issues. Norwell: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Mahony, D., Singson, M., & Mann, V. (2000). Reading ability and sensitivity to morphological relations. Reading and Writing, 12(3), 191–218.

McBride-Chang, C., & Ho, C. S. H. (2005). Predictors of beginning reading in Chinese and English: A 2-year longitudinal study of Chinese kindergartens. Scientific Studies of Reading, 9, 117–144.

McBride-Chang, C., Shu, H., Zhou, A., Wat, C. P., & Wagner, R. K. (2003). Morphological awareness uniquely predicts young children’s Chinese character recognition. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95, 743–751.

McNamara, T. P., Miller, D. L., & Bransford, J. D. (1991). Mental models and reading comprehension. In R. Barr, M. L. Kamil, P. Mosenthal, & P. D. Pearson (Eds.), Handbook of reading research (Vol. II, pp. 490–511). White Plains, NY: Longman.

Muter, V., Hulme, C., Snowling, M. J., & Stevenson, J. (2004). Phonemes, rimes, vocabulary, and grammatical skills as foundation of early reading development: Evidence from a longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 40(5), 665–681.

Nation, K., & Snowling, M. J. (2004). Beyond phonological skills: Broader language skills contribute to the development of visual word recognition. Journal of Research in Reading, 27, 342–356.

Ozono, S. (2002). An empirical study on the effects of logical connectives in EFL reading comprehension. Annual Review of English Language Education in Japan, 13, 61–70.

Ozono, S., & Ito, H. (2003). Logical connectives as catalysts for interactive L2 reading. System, 31, 279–283.

Packard, J., Chen, X., Li, W., Wu, X., Gaffney, J. S., Li, H., et al. (2006). Explicit instruction in orthographic structure and word morphology helps Chinese children learn to write characters. Reading and Writing, 19(5), 457–487.

Perfetti, C. A., Landi, N., & Oakhill, J. (2005). The acquisition of reading comprehension skill. In M. J. Snowling & C. Hulme (Eds.), The science of reading: A handbook (pp. 227–247). Oxford: Blackwell.

Rego, L. L. B., & Bryant, P. E. (1993). The connection between phonological, syntactic and semantic skills and children’s reading and spelling. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 8, 235–246.

Sadoski, M. (1999). Comprehending comprehension. Reading Research Quarterly, 34, 493–500.

Sadoski, M., & Paivio, A. (2007). Toward a unified theory of reading. Scientific Studies of Reading, 11, 337–356.

Samuels, S. J. (2005). Towards a theory of automatic information processing in reading, revisited. In R. B. Ruddell & N. J. Unrau (Eds.), Theoretical models and processes of reading (5th ed., pp. 1127–1148). Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Schweizer, K. (1998). Complexity of information processing and the speed–ability relationship. The Journal of General Psychology, 125(1), 89–102.

Shapiro, L. R., & Hudson, J. A. (1991). Tell me a make-beileve story: Coherence and cohesion in young children’s picture-elicited narratives. Developmental Psychology, 27, 960–974.

Shu, H., & Anderson, R. C. (1997). Role of radical awareness in the character and word acquisition of Chinese children. Reading Research Quarterly, 32(1), 78–89.

Shu, H., Anderson, R. C., & Wu, N. (2000). Phonetic awareness: Knowledge of orthographic-phonology relationships in the character acquisition of Chinese children. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92, 56–62.

Siegel, L. (2008). Morphological awareness skills of English language learner and children with dyslexia. Topics in Language Disorders, 28(1), 15–27.

Sterelny, K. (1990). The representational theory of mind. An introduction. Great Britain: Basil Blackwell Inc.

Tan, L. H., Laird, A. R., Li, K., & Fox, P. T. (2005). Neuroanatomical correlates of phonological processing of chinese characters and alphabetic words: A meta-analysis. Human Brain Mapping, 25(1), 83–91.

Tunmer, W. E., & Hoover, W. (1992). Cognitive and linguistic factors in learning to read. In P. B. Gough, L. C. Ehri, & R. Treiman (Eds.), Reading acquisition (pp. 175–214). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Verhoeven, L., & Perfetti, C. A. (2008). Introduction. Advances in text comprehension: Model, process and development. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 22(3), 293–301.

Yeung, P.-S., Ho, C. S.-H., Chik, P. P.-M., Lo, L.-Y., Hui, L., Chan, D. W., & Chung, K. K.-H. (2011). Reading and spelling Chinese among beginning readers: what skills make a difference? Scientific Studies of Reading, 15, 285–313.

Yeung, P.-S., Ho, C. S.-H., Wong, Y.-K., Chan, D. W.-O., Chung, K. K.-H., & Lo, L.-Y. (2013). Longitudinal predictors of Chinese word reading and spelling among elementary grade students. Applied Psycholinguistics, 34, 1245–1277.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lo, Ly., Ho, C.Sh., Wong, Yk. et al. Understanding the Microstructure and Macrostructure of Passages Among Chinese Elementary School Children. J Psycholinguist Res 45, 1287–1300 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-015-9402-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-015-9402-2