Abstract

A noninferiority randomized trial design compared the efficacy of two self-help variants of the Triple P-Positive Parenting Program: an online version and a self-help workbook. We randomly assigned families of 193 children displaying early onset disruptive behavior difficulties to the online (N = 97) or workbook (N = 96) interventions. Parents completed questionnaire measures of child behavior, parenting, child maltreatment risk, personal adjustment and relationship quality at pre- and post-intervention and again at 6-month follow up. The short-term intervention effects of the Triple P Online program were not inferior to the workbook on the primary outcomes of disruptive child behavior and dysfunctional parenting as reported by both mothers and fathers. Both interventions were associated with significant and clinically meaningful declines from pre- to post-intervention in levels of disruptive child behavior, dysfunctional parenting styles, risk of child maltreatment, and inter-parental conflict on both mother and father report measures. Intervention effects were largely maintained at 6-month follow up, thus supporting the use of self-help parenting programs within a comprehensive population-based system of parenting support to reduce child maltreatment and behavioral problems in children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Increasing calls to make evidence-based parenting programs more widely accessible have led to the development of public health models of parenting support comprising different delivery formats, including large and small group programs, brief low intensity programs, more intensive individually-administered programs, and guided self-help programs (O’Brien & Daley, 2011). However, parents’ participation rates remain a major challenge, as many parents experiencing difficulties with their children’s behavior do not access professional support. Self-help parenting programs have emerged as an alternative to practitioner-delivered programs (O’Brien & Daley, 2011). Online interventions are a relatively recent addition to the parenting literature.

Only two randomized trials provide empirical support for internet-based parenting programs. Both programs evolved from well-established face-to-face parent management training interventions based on social learning principles (Enebrink, Hogstrom, Forster, & Ghaderi, 2012; Sanders, Baker, & Turner, 2012). Enebrink et al. (2012) demonstrated that child conduct problems and dysfunctional parenting improved as a result of online parenting programs. In addition, Sanders et al. (2012) demonstrated the efficacy of an 8-module online version of Triple P (Triple P Online; TPOL). Compared to the internet use as usual condition, the TPOL group showed sustained improvements at 6-month follow up on multiple measures of child, parenting and parental adjustment outcomes with effect sizes ranging from d = 0.40 to 1.10. No studies have examined whether the new online offerings of parent training are as effective as existing workbook-based versions.

The current study examined whether TPOL is as effective as the existing and well-established Every Parent’s Self-Help workbook (Self-Help Triple P; SHTP). A noninferiority approach was used to test the null hypothesis that TPOL is inferior to SHTP by at least a pre-specified and empirically-derived noninferiority margin (H0: μSHTP − μTPOL ≥ δ, where δ is the noninferiority margin) in its effects on disruptive child behavior and parenting. The alternative hypothesis was that TPOL is inferior to SHTP by less than the noninferiority margin (H0: μSHTP − μTPOL < δ). Inferiority approaches are common within the biomedical literature. Their use is becoming increasingly relevant to mental health investigators when the goal is to assess whether a new intervention or intervention modality is clinically and statistically comparable in its effects (i.e., not inferior) to an established and readily available intervention (Greene, Morland, Durkalski, & Frueh, 2008).

We also examined the short- and long-term effects of each intervention on a range of secondary outcomes, including parenting confidence, the quality of the parent–child and parental relationship, parental risk of child maltreatment and parental personal adjustment. We predicted that both TPOL and SHTP would produce improvements at post-intervention that would be maintained at 6-month follow up.

Methods

Participants

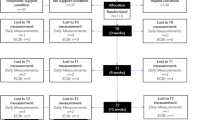

Participants were New Zealand parents of 193 children aged between 3 and 8 years (M = 5.63 years, SD = 1.64 years) displaying elevated levels of disruptive behavior problems. Target children were 67 % male and typically came from New Zealand European backgrounds (90 %). Most children (77 %) lived with their two biological or adoptive parents, and 54 % of families had a combined annual family income of over $NZ70,000Footnote 1 (approximately $US57,600). The mean ages of mothers and fathers in the study were 37.19 years (SD = 5.88 years) and 39.63 years (SD = 6.73 years), respectively. Approximately half the sample was university educated (47 % mothers, 48 % fathers). See Fig. 1 for a description of the participant flow through the study.

Measures

All alpha reliability statistics reported below have been calculated from the present sample.

Child Behavior

Parents completed both the Intensity (α = 0.86) and Problem scales (α = 0.80) of the 36-item Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory (ECBI; Eyberg & Pincus, 1999).

Parenting

Parenting variables were ineffective discipline, parenting confidence and parent–child relationship quality. We measured ineffective discipline using the 30-item Parenting Scale (PS; Arnold, O’Leary, Wolff, & Acker, 1993), which assesses discipline responses on three subscales: Laxness (α = 0.85), Over-Reactivity (α = 0.81), and Verbosity (α = 0.63). Parents’ task-specific confidence in managing difficult child behaviors generally (e.g., temper tantrums) and in different settings (e.g., shopping) was assessed by the Parenting Task Checklist (PTC; Sanders & Woolley, 2005; α = 0.93). Parent–child relationship quality was assessed using 11 items (adapted from Metzler, Biglan, Ary, & Li, 1998; α = 0.83) where parents rated agreement with positive and negative aspects of spending time with their child. Child maltreatment risk was assessed using the risk subscale of a brief version of the Child Abuse Potential inventory (Brief CAP; Ondersma, Chaffin, Mullins, & LeBreton, 2005; α = 0.83) and the 50-item Parental Anger Inventory (PAI; Sedlar & Hansen, 2001; α = 0.95).

Parental Adjustment

Parental wellbeing was measured using the 21-item Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995; α = 0.92), which assessed symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress on a 4-point scale. Interparental conflict over child-rearing (in 2-parent families only) was assessed by the 16-item Parent Problem Checklist (PPC; Dadds & Powell, 1991; α = 0.90). The overall quality of the parent relationship was measured using the Relationship Quality Inventory (RQI; Norton, 1983; α = 0.97).

Parent Satisfaction

At post-intervention, parents completed a 13-item Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ; Sanders, Markie-Dadds, Tully, & Bor, 2000).

Design

The study was a 2 group (TPOL vs. SHTP) by 3 time (pre-intervention, post-intervention, 6-month follow up) repeated measures noninferiority randomized trial. Stratified random assignment to groups was used, controlling for parent’s ethnic group membership (NZ European, Māori, Pacific Islander, Other) and household configuration (one- or two-parent household).

Intervention Conditions

Self-Help Triple P

Parents assigned to the SHTP condition received the Every Parent’s Self-Help workbook (Markie-Dadds, Sanders, & Turner, 1999) by mail after completion of their initial assessment. SHTP includes a series of 10 weekly sessions containing readings, activities and suggested homework tasks for parents to complete.

Triple P Online

TPOL (Turner & Sanders, 2011) is an eight-module behavioral family intervention formatted for delivery over the internet. The program addresses the same content areas and parenting strategies as the workbook. Additional features include video demonstrations, parent-driven branching to review or gain more information, computer-assisted goal setting, probes and exercises to assist parents in checking mastery, and downloadable worksheets, tip sheets and podcasts to review session content and a printable notebook that records parent’s goals and responses to exercises.

Statistical Analyses

To determine whether TPOL was noninferior to SHTP on the primary outcomes of child behavior and ineffective parenting, a noninferiority margin was derived from a previous waitlist control trial of SHTP (Markie-Dadds & Sanders, 2006). This approach was consistent with CONSORT guidelines for noninferiority designs (Piaggio, Elbourne, Altman, Pocock, & Evans, 2006). Based on the recommendation that a clinically unimportant difference between two treatment groups should be one half or less of the historical effect size of the established intervention (Temple & Ellenberg, 2000), we calculated the effect sizes for the parenting and child behavior measures that showed significant improvement at post-intervention relative to the waitlist condition in the trial reported by Markie-Dadds and Sanders; namely the ECBI Intensity (d = 0.86), ECBI Problem (d = 0.89) and PS Over-Reactivity (d = 0.89) scales. When halved, these effect sizes indicated a medium effect, which we considered to be a clinically meaningful difference between the two groups, and therefore too large a difference to be clinically unimportant. We therefore employed an effect size cut-off of d = 0.20 as the margin of noninferiority; if the effect size for the difference between the workbook and online conditions was <0.20, then noninferiority of TPOL can be concluded.

Short- and long-term intervention effects within each condition on all measures were analyzed using a series of 2 condition (workbook vs. TPOL) by 2 time (pre-intervention and post-intervention; post-intervention and 6-month follow up) repeated-measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) or multivariate ANOVAs (MANOVAs; Rausch, Maxwell, & Kelley, 2003). MANOVAs were conducted where multiple measures of the same constructs were used. Effect sizes were calculated for each measure and within each intervention condition to evaluate the level of clinically significant change at post-intervention and 6-month follow up.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

There were no significant group differences on any of the demographic variables or pre-intervention levels of the outcome variables as reported by mothers. Fathers in SHTP reported more problems on the PPC (M = 5.33; SD = 3.70), than those in TPOL [M = 4.02; SD = 3.13; t(142) = −2.29, p = .02].

There was no evidence of attrition bias between groups on either the baseline measures or demographic characteristics except for a significant difference in Brief CAP scores between mothers who did not complete the post-intervention (M = 8.67; SD = 5.61) and those who did [M = 5.79; SD = 4.60; t(188) = 0.28, p = .024].

Noninferiority Analyses on Primary Outcome Measures

For both mother and father reports, the effect size for the difference between the workbook and online conditions was less than the noninferiority cut-off of 0.20 for child behavior (Mothers: ECBI Intensity d = −0.13; ECBI Problem d = −0.09; Fathers: ECBI Intensity d = −0.14; ECBI Problem d = −0.16) and ineffective parenting (Mothers: PS Over-Reactivity d = −0.03; Fathers: PS Over-Reactivity d = 0.05). Thus, TPOL produced short-term intervention effects for child behavior and dysfunctional parenting that were noninferior to the effects of SHTP.

Short- and Long-Term Intervention Effects

All univariate F values and effect sizes for effects of time at post-intervention and 6-month follow up appear in Tables 1 and 2.

Child Behavior

There was a significant multivariate decrease in disruptive behavior from pre- to post-intervention by both mothers’ [F(2, 171) = 199.09, p < .001] and fathers’ reports [F(2, 117) = 44.36, p < .001], and significant univariate decreases for both scales on the ECBI. These effects were maintained at follow up for fathers; there was no significant multivariate effect of time [F(2, 97) < 1.00, ns] from post-intervention to 6-month follow up. However, there was a significant multivariate effect of time for mothers [F(2, 156) = 4.66, p = .011] and a significant univariate effect of time for the ECBI Intensity scale, indicative of a small but significant increase in the intensity of disruptive child behavior from post to follow up.

Parenting

The short-term multivariate effect for time on ineffective parenting was significant for mothers [F(3, 170) = 97.53, p < .001] and fathers [F(3, 116) = 12.42, p < .001] and there were significant univariate decreases over time on all three scales on the PS. For fathers, the significant short-term intervention effects were maintained at follow up; there was no multivariate effect of time [F(3, 96) < 1.00, ns]. In contrast, the multivariate effect of time was significant for mothers [F(3, 155) = 12.07, p < .001], suggesting that across both conditions, there were increases in the use of ineffective parenting strategies at follow up.

Significant improvements in parenting confidence occurred for both parents and both interventions, with a multivariate effect of time for mothers [F(2, 171) = 173.30, p < .001] and for fathers [F(2, 117) = 19.78, p < .001]; these improvements were maintained for both parents. There was no multivariate effect of time from post to follow up for mothers [F(2, 156) = 2.36, ns] or for fathers [F(2, 97) = 1.19, ns]. Improvements in parent–child relationship quality were also evidenced at post-intervention, and the significant univariate effect of time from post to follow up for mothers indicated that there were continued long-term improvements in mother–child relationship quality. The effect of time for fathers from post to follow up was not significant.

Child Maltreatment Risk

There was a significant multivariate effect for time from pre to post for both parents [F(2, 171) = 35.40, p < .001 for mothers; F(2, 117) = 4.57, p = .012 for fathers], but no significant time effect for either parent from post to follow up [F(2, 156) = 2.56, ns for mothers; F(2, 97) = 1.25, ns for fathers].

Parental Adjustment

There was a significant multivariate improvement in parental wellbeing from pre- to post-intervention for both parents in both treatment conditions [F(3, 170) = 23.77, p < .001 for mothers; F(3, 116) = 7.40, p < .001 for fathers]. For mothers, the univariate effect of time was significant for all three scales on the DASS, while for fathers it was significant for stress only. These improvements were maintained at 6-month follow up as there was no significant multivariate effect of time [F(3, 155) < 1.00, ns for mothers; F(3, 96) = 2.21, ns for fathers].

Parental Relationship Functioning

The multivariate effect of time from pre- to post-intervention was significant for mothers [F(3, 144) = 33.00, p < .001] and fathers [F(3, 112) = 12.31, p < .001], with the univariate effects of time significant for mother- and father-reported conflict over child-rearing on the PPC Extent and Problem scales but not the RQI. From post-intervention to follow up, there was a significant multivariate effect of time for both parents [F(3, 128) = 5.51, p = .001 for mothers; F(3, 94) = 2.75, p = .047 for fathers]. Mother-reported conflict over discipline issues on the PPC Problem and Extent scales significantly increased at long-term follow up and there were significant declines in relationship quality on the RQI for both parents.

Client Satisfaction

There were no significant differences in either mothers’ level of satisfaction between SHTP (M = 67.34, SD = 14.06) and TPOL [M = 68.66, SD = 12.17; t(172) < 1.00, ns], or for fathers’ level between the SHTP (M = 64.31, SD = 12.28) and TPOL groups [M = 63.36, SD = 14.06; t(118) < 1.00, ns].

Discussion

This study showed that the effects of TPOL were not significantly different from the existing self-help program, confirming our central hypothesis. Both interventions were associated with improvements in child disruptive behavior, positive parenting, family relationships, and parental adjustment producing effects comparable to other evaluations of Triple P interventions at the same level of intensity. These findings suggest that both self-directed variants tested are viable cost efficient programming options for parents of children with early onset conduct problems that could greatly improve population reach. Since parents with higher child abuse potential were less likely to complete post-intervention assessment, further research is needed to clarify whether the provision of professional contact (e.g., by telephone, email, text messaging, video conference or in person) enhances both participation in outcome assessments and program completion for vulnerable, high-risk or disadvantaged parents.

Noninferiority and equivalence designs are seldom used in mental health research and when they are used, they are often improperly applied or misinterpreted (for a comprehensive review of the use of these designs in mental health trials see Greene et al., 2008). Given that the superiority of parenting interventions to no intervention or wait list control conditions is well established, the present study demonstrated the usefulness of noninferiority designs in testing the efficacy of new interventions or intervention modalities. Such analyses will become increasingly important as policy makers push to make a range of evidence-based options available to parents to enhance the population reach of parenting interventions.

Notes

The median annual family income in New Zealand in 2010 was $NZ64,272 (Statistics New Zealand, 2010).

References

Arnold, D. S., O’Leary, S. G., Wolff, L. S., & Acker, M. M. (1993). The Parenting Scale: A measure of dysfunctional parenting in discipline situations. Psychological Assessment, 5, 137–144. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.5.2.137.

Dadds, M. R., & Powell, M. B. (1991). The relationship of interparental conflict and global marital adjustment to aggression, anxiety and immaturity in aggressive nonclinic children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 19, 553–567. doi:10.1007/BF00925820.

Enebrink, P., Hogstrom, J., Forster, M., & Ghaderi, A. (2012). Internet-based parent management training: A randomized controlled study. Behavior Research and Therapy, 50, 240–249. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2012.01.006.

Eyberg, S. M., & Pincus, D. (1999). Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory and Sutter–Eyberg Student Behavior Inventory-revised: Professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Greene, C. J., Morland, L. A., Durkalski, V. L., & Frueh, C. (2008). Noninferiority and equivalence designs: Issues and implications for mental health research. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 21(5), 433–439. doi:10.1002/jts.20367.

Lovibond, S. H., & Lovibond, P. F. (1995). Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales (2nd ed.). Sydney, NSW: Psychology Foundation of Australia.

Markie-Dadds, C., & Sanders, M. R. (2006). Self-directed Triple P (Positive Parenting Program) for mothers with children at-risk of developing conduct problems. Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 34(3), 259–275. doi:10.1017/S1352465806002797.

Markie-Dadds, C., Sanders, M. R., & Turner, K. M. T. (1999). Every parent’s self-help workbook. Milton: Families International.

Metzler, C. W., Biglan, A., Ary, D., & Li, F. (1998). The stability and validity of early adolescents’ reports of parenting constructs. Journal of Family Psychology, 12, 1–21. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.12.4.600.

Norton, R. (1983). Measuring marital quality: A critical look at the dependent variable. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 45, 141–151. doi:10.2307/351302.

O’Brien, M., & Daley, D. (2011). Self-help parenting interventions for childhood behavior disorders: A review of the evidence. Child: Care, Health and Development, 37(5), 623–637. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01231.x.

Ondersma, S. J., Chaffin, M., Simpson, S., & LeBreton, J. (2005). A brief form of the brief child abuse inventory: Development and validation. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 34(2), 301–311. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp3402_9.

Piaggio, G., Elbourne, D. R., Altman, D. G., Pocock, S. J., & Evans, S. J. W. (2006). Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized controlled trials: An extension of the CONSORT statement. Journal of the American Medical Association, 295(10), 1152–1160. doi:10.1001/jama.295.10.1152.

Rausch, J. R., Maxwell, S. E., & Kelley, K. (2003). Analytic methods for questions pertaining to a randomized pretest, posttest, follow-up design. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 32(3), 467–486. doi:10.1207/S15374424JCCP3203_15.

Sanders, M. R., Baker, S., & Turner, K. M. T. (2012). A randomized controlled trial evaluating the efficacy of Triple P Online with parents of children with early-onset conduct problems. Behavior Research and Therapy, 50(11), 675–684. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2012.07.004.

Sanders, M. R., Markie-Dadds, C., Tully, L. A., & Bor, W. (2000). The Triple P-Positive Parenting Program: A comparison of enhanced, standard and self-directed behavioral family intervention for parents of children with early onset conduct problems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 624–640.

Sanders, M. R., & Woolley, M. L. (2005). The relationship between maternal self-efficacy and parenting practices: Implications for parent training. Child: Care, Health and Development, 31(1), 65–73. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2005.00487.x.

Sedlar, G., & Hansen, D. J. (2001). Anger, child behavior, and family distress: Further evaluation of the parental anger inventory. Journal of Family Violence, 16, 361–373. doi:10.1023/A:1012220809344.

Statistics New Zealand. (2010). New Zealand income survey: June 2010 quarter. Wellington: Statistics New Zealand.

Temple, R., & Ellenberg, S. S. (2000). Placebo-controlled trials and active-controlled trials in the evaluation of new treatments. Medicine and Public Issues, 133(6), 455–463.

Turner, K. M. T., & Sanders, M. R. (2011). Triple P Online [interactive internet program]. Brisbane, QLD: Triple P International.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sanders, M.R., Dittman, C.K., Farruggia, S.P. et al. A Comparison of Online Versus Workbook Delivery of a Self-Help Positive Parenting Program. J Primary Prevent 35, 125–133 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-014-0339-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-014-0339-2