This paper reports on an electronic mentoring program, the Digital Heroes Campaign (DHC), in which 242 youth were matched with online mentors over a two-year period. Survey, focus group, and interview data, in addition to analyses of the e-mails that pairs exchanged, were examined in order to assess the nature, types, and quality of the relationships that were formed. Despite youths’ generally positive self-reports, deep connections between mentors and mentees appeared to be relatively rare. The findings suggest that online mentoring programs face significant challenges and that further research is needed to determine under what conditions online mentoring is likely to be most effective.

Editors' Strategic Implications: Given the infrequent occurrence of close connections, youth mentoring practitioners and researchers must consider whether online mentoring is likely to promote the kind of “relationships” that might be expected to promote positive youth development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The presence of caring adults has long been recognized as an important resource in the lives of vulnerable youth (Rhodes, 2002). Youth who have natural mentors (i.e., relationships not established through mentoring programs) have been found to hold more favorable attitudes toward school and to be less likely to engage in a range of problem behaviors than youth without such mentors (Beier, Rosenfeld, Spitalny, Zansky, & Bontempo, 2000; Zimmerman, Bigenheimer, & Notaro, 2002). Unfortunately, many children and adolescents do not readily find supportive non-parent adults in their communities. Changing family and marital and employment patterns, overcrowded schools, and less cohesive communities have dramatically reduced youths’ ready access to caring adults (Eccles & Gootman, 2002; Putnam, 2000). Mentoring programs are increasingly being promoted to redress the decreased availability of adult support and guidance (Grossman & Tierney, 1998; Rhodes, 2002).

Although formal mentoring has traditionally been thought of as one-to-one, face-to-face relationships between youth and unrelated adults, a growing number of programs have begun to experiment with online mentoring relationships. The increasing interest in this approach has been fueled by its relative convenience, coupled with the tremendous growth in online forms of communication. To date, online mentoring has tended to serve as an adjunct to face-to-face meetings but in some cases it is the primary means of connecting caring adults with youth. Numerous formal online mentoring programs are now in place, and many are integrated into classrooms or after-school settings (Cravens, 2003). These programs have varying goals, formats, and durations. For example, some focus on career or school outcomes, while others seek broader developmental growth. Whereas one program might involve individual matches that last for years, another might consist of groups of mentors paired with entire classrooms for specific, time-limited activities. Finally, the relationships might entail sending one email per week, spending several hours per week reviewing students’ class projects, or sending notes as a bridge between face-to-face meetings (O'Neill, Wagner, & Gomez, 1996).

Despite this expanding array of programs and venues (e.g., e-mail, chat rooms, instant messaging) and the general interest surrounding the topic of online mentoring, little is known about its relative advantages and disadvantages or the nature of the relationships that are formed through this medium. By far the most significant advantage appears to be freedom from the conventions of geography and time (Ensher, Heun, & Blanchard, 2003). Many mentors face difficulties arranging a time to travel to their mentees’ homes and schools, and missed meetings and premature terminations of relationships are common hazards in the field. Online mentoring permits mentors and mentees to correspond in a more spontaneous fashion, and can engage a wider range of adults (e.g., including physically disabled persons or busy corporate executives) to serve as mentors. In addition to broadening the pool of available mentors, online communication may appeal to a different set of youth, including those who are too shy or withdrawn to reach out to people around them (Scealy, Phillips, & Stevenson, 2003). Online mentoring also removes barriers created by snap first impressions, often based on physical appearance, providing mentors and mentees with the opportunity to focus on deeper commonalities that have the potential to bind them together (Ensher & Murphy, 1997). In fact, for some youth and mentors, the Internet can have a disinhibiting effect, leading to increased levels of honesty and self-disclosure (Miller & Griffiths, 2005). Finally, the presence of a written record provides a convenient way to supervise and monitor the relationship, creating a rich archive of data from which to conduct evaluations of mentoring processes and outcomes.

Perhaps offsetting these potential benefits are the complications inherent in online mentoring (McCurdy, 2003). For instance, this form of mentoring appears more vulnerable to miscommunications, including misinterpretations of attempts at humor and sarcasm, misreading of the tone of a message, and failures to pick up on and redress misunderstandings. Furthermore, the lack of personal contact and lower inhibitions can result in angry or hurtful comments that would be less likely to occur in person. Indeed, the lack of voice tone and other nonverbal forms of communication may ultimately preclude the development of close ties (Ensher, Heun, & Blanchard, 2003).

Some people might be less inclined to make personal disclosures and share emotions online, tending to use e-mail for more superficial or informational communications (Kraut et al., 1998). There are also the related issues of confidentiality, litigation, and written records, which dampen disclosures and may have a distancing effect on the relationship. For example, although mentors’ authentic online discussions of their human side—their vulnerabilities and past mistakes—can go a long way toward relationship building with adolescents (Bennett, Hupert, Tsikalas, Meade, & Honey, 1998), mentors may feel hesitant to create a written record of this nature. On a practical level, online communication requires that both parties have regular access to a computer and the Internet, as well competency with these instruments, which may be unrealistic in some low-income communities (Price & Chen, 2003; Sanchez & Harris, 1996). Similarly, online mentoring programs can present unique practical and technical challenges that make it difficult for staff to coordinate and manage (Cravens, 2003).

Much of the discussion around online mentoring has been speculative or based on research that involves very small samples and cross-sectional data. Few peer-reviewed articles have been published on the topic, and most of the information that is available through websites is limited to program descriptions (Miller & Griffiths, 2005). When success is measured, it is often in terms of the number of new matches that have been made, as opposed to their intensity, duration, or effectiveness. Despite this dearth of information, people tend to hold strong opinions about online mentoring, debating whether the Internet promotes or undercuts social connections (Mundorf & Laird, 2002; Rheingold, 1993; Turkle, 1996), and whether online relationships can ever be as influential as those sustained through face-to-face interaction (Kraut et al., 1998).

It is questionable whether relationships that are maintained solely via the Internet can compete with, and even supplant, relationships that involve face-to-face contact. Kraut and colleagues (1998) demonstrated that relationships forged solely through email correspondence tended to be “weak ties.” Such ties are characterized by less contact and a more narrow focus, resulting in more superficial and easily broken bonds. They are contrasted with “strong ties,” characterized by frequent contact across many life areas, deep affection, and mutual obligation, which are associated with better social and psychological outcomes (Granovetter, 1973; Kraut et al., 1998). The researchers surmised that, because individuals who meet solely online do not have access to the broader context of each other's lives, they are less able to engage in deep, supportive discussions. These findings are noteworthy particularly in light of recent research that suggests that the benefits of mentoring may be more likely realized when youth and their mentors form a close relationship (Grossman & Rhodes, 2002; Parra, DuBois, Neville, & Pugh-Lilly, 2002)

Despite these discouraging findings, it appears possible that ongoing e-mail exchanges can eventually lead to stronger ties, and evidence from related fields provides grounds for cautious optimism about the potential value of online mentoring. For example, Salem, Bogat, and Reid (1997) evaluated an online mutual-help group for people suffering from depression and found that participants communicated in ways that were characteristic of face-to-face groups (sharing high levels of support, acceptance, and positive feelings), and that group involvement led to improvements in well-being. Research on e-therapy is also relevant to online mentoring. There are over 200 online therapy sites providing access to hundreds of online counselors (Segall, 2000), and preliminary observations indicate that online counseling has the potential to address some of the difficulties that clients bring to therapy (Hatcher, 2002). Also, the Internet may aid in the supervision of mentors. Although counselors generally rate face-to-face supervision as more effective than online supervision, the latter has proven to be a convenient way of obtaining guidance on a range of issues (McCurdy, 2003).

Empirical study of online mentoring is greatly needed in order to begin to address these issues about which we are now only able to speculate. This paper reports findings from a process study of an online youth mentoring program, the Digital Heroes Campaign (DHC). The DHC is an electronic mentoring program developed by AOL Time Warner (AOLTW) and People magazine, in conjunction with PowerUP and the National Mentoring Partnership/MENTOR. The goal of the program is to promote positive development and prevent problems in behavioral, academic, and psychosocial functioning through the establishment of a one-on-one relationship between a youth and a caring adult. Between 2000 and 2002, DHC matched nearly 242 youth (aged 13 through 17) with adults in exclusively online relationships. This study is based on a number of sources—interviews with a subset of mentors and supervisors, focus groups with a subset of youth, and content analysis of e-mail correspondence. Given that online mentoring is a relatively new phenomenon, the primary focus of this effort was to understand the nature, types, and quality of the relationships that developed in this type of mentoring program.

METHOD

Participants

Over a two-year period, 272 youth between the ages of 12 and 18 were recruited by youth-service agencies across the United States for the DHC project. They were matched with mentors with whom they were intended to correspond exclusively via e-mail on a weekly basis for a minimum of 6 months during the school year. From this initial sample, 242 pairs exchanged e-mails. Over half of the youth involved in these matches were African American (59%), 13% were Latino, 7% White, and 21% were of another racial/ethnic background or were multi-racial. The average age of the youth participants was 15.4 (SD=2.1 years), and slightly more than half (53%) were female. Among the youth who participated in Year 2, 34% lived with both of their parents, 57% lived with one parent, and 9% lived with neither parent. The parents and/or guardians of the youth signed an agreement allowing their children to participate and acknowledging that they understood the privacy and security requirements of the program.

A sample of 267 mentors was recruited, among whom 242 went on to participate in matches that exchanged e-mails. The mentors included AOLTW employees from across the country (87%), as well as a smaller sample of American celebrities or “notable” individuals recruited by People magazine (13%). Although AOLTW employees were encouraged to volunteer, there was no pressure to do so, and no sanctions or rewards were tied to participation. Corporate emails were sent to employees and notices were posted in AOLTW newsletters. Interested employees then completed and submitted an application form online. The president of People sent a letter to potential mentors—individuals deemed by People to be “notable” within a wide range of occupational fields across the country. Interested individuals then submitted an application. All interested volunteers, whether recruited through AOLTW or People, were interviewed by phone before being selected for participation in the program. Prior to their acceptance as mentors, volunteers were also required to undergo a background check conducted by a private security firm. Once accepted, mentors completed a three-hour training program at local sites that were affiliated with the National Mentoring Partnership. The training was designed to help prepare volunteers for their role as online mentors.

AOLTW, People magazine, and the local sites worked with the National Mentoring Partnership to match each youth with a mentor. Using personal profiles written by the youth and adult volunteers, the needs and interests of the youth and similarities between the two parties were examined. In light of safety concerns, AOLTW developed state-of-the art technology and safeguards for DHC to ensure that only the participating youth and mentors could communicate with one another. Originally, each participant had a DHC specific e-mail address that was routed through the AOLTW system. Since many participants found the use of DHC emails cumbersome, AOLTW developed a system that enabled them to use their own addresses to send and receive e-mail. These email addresses were then routed and encrypted through the secure system, so that their counterpart could not see the actual e-mail address.

Procedures

Email Correspondence

All of the emails exchanged between the mentoring pairs were archived (2,926 in Year 1, and 3,424 in Year 2). Participants were informed of this procedure at the outset. To protect privacy, the names of participants were coded and then removed from the emails prior to analysis. To make analysis of all of the e-mails exchanged between mentor-mentee pairs manageable, the following data reduction strategy was used. All of the pairs were grouped by the total number of messages exchanged between that pair (0–10, 11–20, and so on). Within each grouping, all of the messages exchanged between a random subsample (52%) of the pairs was read and coded by two data analysts. The two analysts worked independently with the qualitative data and then came together to discuss and resolve discrepancies. E-mails were analyzed in two ways: (1) a narrative analysis of the content of the messages was conducted to determine the types of relationships formed, specifically focusing on the depth of the connection between the pairs, and (2) the messages were coded using a numeric system described below to assess the overall relationship quality.

To examine whether different types of e-mentoring relationships developed, a modified form of holistic content coding (Lieblich, Tuval-Mashiach, & Zilber, 1998) of the Year 1 and Year 2 emails was conducted by two data analysts. The depth of the connections formed was of central interest given the mounting empirical evidence that closer, more enduring relationships yield positive benefits for the youth participants (Grossman & Rhodes, 2002; Parra, DuBois, Neville, & Pugh-Lilly, 2002). Thus, the following questions guided the coding of the e-mailed correspondence: (a) did the mentor and young person truly seem to enjoy “listening” and “talking” to each other, albeit through printed words, (b) were they both engaged and responsive to each other, and (c) were their correspondences occasionally personal and/or about something important to the writer and/or receiver?

A modified version of a holistic-content approach to coding (Lieblich et al., 1998) was used to analyze the email exchanges. This form of narrative analysis facilitates analyzing the thematic content of texts while also considering the larger contexts within which themes appear. This is accomplished by repeatedly reading through the narratives intact rather than beginning by chunking the data and looking for themes within these reduced sections of the narrative. For the present analysis, two analysts read the entire set of e-mails exchanged by selected pairs multiple times and documented their “global impressions” (Lieblich et al., 1998) of the nature of the relationship formed between each pair—how closely connected, mutually responsive, and engaged in the relationship each participant seemed to be. The next step in the holistic-content approach is to identify specific themes or foci to track within each individual narrative. In this case, the e-mails between all of the identified pairs were read in light of the key questions identified above to determine the depth of this connection.

E-mails were then numerically coded for quality on a scale from 1 (lowest quality) to 4 (highest quality) on the basis of the several dimensions. Based on the content and tone of the e-mails, the raters assessed the extent to which: (1) the relationship seemed youth-centered, (2) the mentor seemed emotionally engaged, (3) the mentee seemed emotionally engaged, (4) the mentor was responsive to the mentee, (5) the mentee was responsive to the mentor, (6) the mentor seemed satisfied with the relationship, and (7) the mentee seemed satisfied with the relationship. Based on these criteria, the relationship was assessed for quality. Here again, this rating was conducted independently by two coders who then discussed and resolved discrepancies.

Mentor Surveys

Post-program surveys (Table I) completed by the mentors, focused on mentors’ perceptions of the program, of the adequacy of the training and support they received from national staff, and of the benefits of participation, both for themselves and for the youth they mentored. The mentor survey included 16 questions. Some examples include: “Do you find talking with your mentee … Very easy, Fairly easy, Fairly difficult, or Very difficult,” and “To what extent, if any, do you think your mentee benefited from your mentoring relationship … A lot, Somewhat, Not at all, or Don't know.” The survey also included two open-ended questions concerning recommendations and final comments. It was developed as an online questionnaire, although a few of the mentors recruited by People magazine completed a paper version of the survey. The overall response rate for the mentors to the post-program survey was 48% in Year 1, and 60% in Year 2.

Interviews with Mentors

Telephone interviews were conducted with a sub-sample (n=30; 17 in Year 1 and 13 in Year 2) of the participating mentors, who were selected by program staff at AOLTW (a sample of those with successful and unsuccessful relationships) and People magazine (those deemed most accessible). These interviews were used to clarify information gathered from the mentor surveys. A standard protocol covered issues related to how mentors got involved and what had made them want to volunteer. They were also asked about their perceptions of the training, their support from and communication with program staff, and their satisfaction with the program. Notes taken by the interviewers were later content analyzed to identify common themes.

Interviews with Site Supervisors

A total of 12 site supervisors were interviewed through either face-to-face or telephone interviews. The interview consisted of a standard protocol focused on the supervisors’ overall assessment of a number of factors, including the training and support they received, how they recruited and supported youth in the program, and any challenges posed by the technology. During the interviews, analysts took notes that were later content analyzed to identify common themes.

Focus Groups with Youth

A total of three focus groups were conducted with youth in Year 1, and four were conducted with youth in Year 2. All youth participating in the program at four sites visited by researchers were invited to participate. These focus groups (of eight to ten youth) provided in-depth information regarding the youth's perceptions of DHC and their specific mentors. The focus group protocol addressed such topics as how youth heard about and became involved with the program, the training and the support they received, their perceptions of their relationship with their mentor, benefits of the program, and recommendations. Content analysis of the focus groups was conducted.

RESULTS

Contact and Match Duration

During Year 1, the pairs exchanged an average of 22.50 e-mails, while during Year 2 this number increased to 30.57. The total number of emails exchanged by pairs ranged from 2 to 74 in Year 1 and from 3 to 147 in Year 2. During Year 1, the number of e-mails written by mentors and mentees was fairly balanced, whereas during Year 2, mentors sent more emails to their mentees than they received. Although mentors made a 6-month commitment, only about half (51%) of the relationships in Year 1 and Year 2 combined lasted for six months or longer, with 19% continuing for three months or less.

Relationship Quality

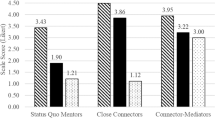

As shown in Table II, the relationships were rated as being of relatively high quality. The relationships tended to be youth-centered and both mentors and youths were relatively engaged and satisfied. The lowest score (2.93) was for youth responsiveness, indicating that several mentees exhibited lapses of one to three weeks between their e-mails.

Relationship Closeness

The depth of the e-mail conversations between mentors and youth fell into four broad categories: (1) disengaged relationships in which long periods of time elapsed between contacts, (2) exchanges that were largely superficial and impersonal, (3) exchanges that were characterized by friendly, mutual sharing, and (4) deeper discussions of more personal issues. Pairs whose interactions were characterized by the latter two descriptions tended to exchange 30 or more e-mails over the course of the relationship (6 to a maximum of 9 months). Although it was possible to distinguish more superficial relationships from closer relationships according to e-mail frequency, this measure did not distinguish warm and friendly relationships from deeper, more personal relationships. This finding suggests that although frequency of contact may be critical for relationship formation, it does not necessarily lead to deeper connections. Below are examples of the four broad categories of relationship closeness that were detected.

Disengaged relationships—“I’m sorry I haven't written.” Failures to remain in regular contact were much more frequent in Year 1; however there were some that fell into this category in Year 2. Although both mentors and mentees failed to correspond regularly, the pleas by youth to their mentors for a response were particularly poignant. Below are the first and last in a series of six messages sent by a young person to the mentor requesting a response.

From: Youth

Received: Nov 9 2000 4:26PM

Subject: HELLO

HI (Mentor)! I got your e-mail two weeks ago. Thanks for sending me one! I would like to hear from you really soon. I would like to know how you first got into being an #######, and how is it. Please respond. THANX!!!!

From: Youth

Received: Dec 18 2000 5:41PM

Subject: Where Are You?

Dear (Mentor), Hi, this is Y. I'm just wondering where are you? I hope you respond to me sooner or later. I would really love to hear from you. Thanks!!!! Y

Such failures to respond may be analogous to not showing up in face-to-face mentoring.

Superficial and impersonal exchanges—“How's the weather?” Some relationships never seemed to get off the ground. In these matches, mentors appeared to have difficulty engaging their mentees, while mentees seemed uncomfortable or unfamiliar with making personal disclosures and rarely wrote more than a few brief impersonal sentences. In many cases, the mentors made repeated efforts to engage their mentees, by sharing information about themselves, expressing interest in their mentee's interests, school, and daily life, and searching for a topic that would engage their mentee. Despite these efforts, the mentees replied only occasionally with short and impersonal e-mails. For example:

From: Youth

Received: Feb. 4

Subject:

how are you ?

i am fine.

what have you been doing have a nice day love Y

From: Mentor

Received: Feb. 5

Subject: Hey Y

Dear Y:

… Tell me more about school. I want to know what you are thinking about for the future. Do you want to go to college? Do you want to do a certain job when you graduate high school? Have you thought about the college scholarships you could get? It really helped me when I went to college.

How is your family?

I look forward to your answers to the above questions … lets start talking about this …

Love, M

From: Youth

Received: Mar. 19

Subject: HI

IT'S Y HI HOW ARE YOU? I AM FINE. WHAT ARE YOU DOING. LOVE Y

In other matches that never moved beyond this superficial stage, the pairs seemed to be out of sync with one another, pursuing different topics and threads of the conversation.

Friendly, mutual sharing exchanges—“Hey, how's it going?” This was the most common type of e-mentoring relationship among the DHC pairs and was characterized by friendly, warm, reciprocal interactions that did not, however, typically extend to the discussion of serious personal issues. These pairs kept in contact on a fairly regular basis, with occasional lapses of a few weeks, and their e-mails indicated that they enjoyed their exchanges. In some cases, advice was sought and shared, particularly about important decisions that mentees faced, for example regarding college applications and career paths. The pair who exchanged the following messages had been matched for approximately two months:

From: Youth

Received: Feb. 8

Subject: Just to say hi!!!!

Yea i got your last e-mail and i thought i told you that Flyy Gyrl was my favorite book and math ever sence i found out i was good in it and Olamide is a dude from a fromer group imajin and now they broke up but soon as i find a nice pic of him imma e-mail it ro you and naw you not that old my mom(46) and dad (49) is old

From: Mentor

Received: Feb. 14

Subject: Just to say hi!!!!

Thanks. For some reason that e-mail didn't get through but now I have two to the same! Go figure. It's computers. Sometimes they make me crazy!

Tell me about the book Fly Gyrl. Why do you like it? Who's the author? Maybe I'll read it so we can discuss it in e-mail.

I'll also check out your singer. Will she be at the Grammy's?

I'm on my way to Paris for a business meeting and will be gone for a week.

Any questions for me? Keep them easy!

HAPPY VALENTINE'S DAY!!!!

From: Youth

Received: Feb. 14

Subject: Just to say hi!!!!

Well happy Valentine's Day to you too!! Well hows your day going well first let me tell you what i got for Valentine's 4 ballons 3 teddies and candy and roses but i gave it away cuz i didn't want to carry it!!! How lazy!!! lol

Well Omar Tyree wrote that book Flyy Gyrl!!

Well i told you my sis had her baby right!!! well now everyone call Him my baby!! Cuz … the baby is in love with me and when people go and pick him up he start crying if i'm not arround even if it's his mom but that's gonna be my baby for life … well i hope yo have fun in paris my mom is from France i can't remeber what part but i know she was born there …

… well at first i tyhought you will be like my mom or whateva but i found out that you're like a sista to me now …

The emails exchanged by pairs in this group indicated that the mentor and youth had forged an honest connection and enjoyed their exchanges. Although some of the youth might, over time, grow comfortable confiding in their mentors, discussions did not encompass more personal topics of conversation.

Deeper discussions—“It was a rough day.” Some pairs talked frankly about personal issues and problems. Several youth confided in their mentors and actively sought advice about problems they were having with friends, with family, and at school. Others asked for suggestions and information about important decisions they had to make, such as where and how to apply for college. Some also discussed broad social issues such as racism, religion, politics, crime, and safety, particularly as these related to the neighborhoods in which the youth or mentor lived. The following is an example of an exchange involving personal advice that occurred approximately three months into this e-mentoring relationship:

From: Youth

Received: Feb. 15

Subject: school

Today in school I had a bad day. It started out because I didn't want to take off my coat. So they wanted me out of my class. So I started to yell at my teacher. Then I ask my teacher can I go home.

What I did was worng but can you help. I need some advice.

From: Mentor

Received: Feb. 16

Subject: school

I know sometimes you just don't feel like doing something, and then you get angry and say things you shouldn't. That's what it sounds like when you had a bad day at school since you didn't want to take your coat off and when they wanted you out of class you started to yell at your teacher. I am sure you understood that was not the right way to react but at times we make mistakes. It is important to learn from bad days like that so you can apologize to your teacher (who has your best interests at heart) and try to control your feelings. We all have days like that and everyone makes mistakes, but we just have to improve and try not to let it happen again. I know you are a good person and you want to do well in school so you can go on to the next stage in your life. I have faith in you. Let me know how you are doing now. I am always here by e-mail to “talk” to you.

The exchanges between this pair continued in this vein as the youth asked for further advice about anger management and the mentor continued to coach the youth and to offer encouragement. For some of the pairs within this group, this depth of personal sharing occurred relatively quickly while others needed more time to build trust.

Youth Outcomes

In the focus groups, mentees indicated that their mentors had helped to expand their awareness of the possibilities available to them, specifically noting that they had learned more about careers and colleges and about how to prepare for both. For example, one youth stated, “It was exciting because since I was interested in writing, I got hooked up with an author who gave me background information about how he got to where he is.” Some indicated that their mentors had helped them to obtain part-time or summer jobs. Several youth, particularly those matched with the People magazine mentors, reported learning that even famous or important people started out “just like regular people.” As one youth reported, “I learned that although they are very important people, they come from similar backgrounds as me.”

In interviews, mentors indicated that they perceived some changes in their mentees. Most mentors believed that participation in DHC had broadened their mentees’ horizons and had helped them begin to plan their future. For example, one mentor stated, “Talking with someone you’ve never met—it improves communication skills, understanding of the rest of the world and other lifestyles.” Another mentor, reflecting on his mentee, reported that: “he didn't have a real parental figure around all of the time. He learned the Socratic way; I’d ask him questions that got him to realize he has his own answers. I think he learned how to make a daily, weekly, yearly, 3-year, and a 5-year plan. I think he has some more confidence. Making some good decisions, making some goals. Not putting too much attention on his failures.”

DISCUSSION

This exploratory study suggests that in order for online mentoring to serve as a viable venue for the promotion of meaningful relationships between youth and unrelated adults, more attention must be paid to understanding the conditions under which such relationships are likely to develop. Analyses of the e-mail exchanges indicated that these online relationships tended to be of relatively high quality, in that they were youth-centered and both the mentors and mentees seemed emotionally engaged and satisfied with the relationship. However, there was considerable variability in the depth of the connections formed through this medium. The qualitative analysis of the e-mail exchanges in particular revealed that although some pairs engaged in deep conversations indicative of closer connections, these exchanges were relatively rare.

Given that about half of the online relationships dissolved within a few months, this is not particularly surprising. It is, however, cause for concern, as there is evidence that shorter-than-expected, face-to-face mentoring relationships can be detrimental to youth (Grossman & Rhodes, 2002; Slicker & Palmer, 1993). Some mentors and mentees may need more time to get to know one another before they are willing to engage in more personally revealing conversations. It is also possible that expectations for online relationships may be different, with some youths and adults feeling greater freedom to self-disclose in this format. For others the lack of personal contact may make it less likely that they would ever feel comfortable delving into more personal topics online. This may explain, in part, why there was little difference between the numbers of emails exchanged by the pairs whose relationships were friendlier as compared to those whose connections seemed to run the deepest.

It may be particularly important for online mentoring relationships to have a specific focus. Among those relationships in this study that never seemed to get off the ground, it may have been that either the mentor or the youth was uncertain how best to use the online format and so the contacts never moved beyond brief superficial exchanges. It has been suggested that online mentoring may be more effective when it is built around a defined project or area of learning and growth (National Mentoring Center, 2002). Although the topics of conversation in the e-mail exchanged between mentors and mentees ran the gamut from daily activities and favorite music to problems the young people were having with friends or teachers, the youths’ perception was that current schooling and future plans for continued education and employment along with the mentor's own career paths were some of the more frequently discussed subjects. Some youth who were connected with a mentor whose career was of interest to them expressed particular enthusiasm for the program. Others indicated that it was helpful to them to learn that adults who are successful were also simply people who in some cases had struggled to find their way. The enthusiasm of the youth who participated in this program for learning about the paths that their adult mentors took in their own lives suggests that online mentoring relationships may be well-suited to providing youth additional adult support as they navigate their day-to-day educational experiences and plan for the future.

The relatively lower rating of youth responsiveness in the analysis of the email exchanges may be attributable to several factors. Some of the mentees (and even mentors) may have been constrained by low levels of computer literacy or even comfort communicating in a written rather than oral format. Beyond computer literacy, some youth may need more assistance than others with figuring out how best to engage in an online relationship with an adult mentor in a way that it is meaningful for them. Part of the appeal of online mentoring programs is the perception that they are much less expensive than face-to-face programs. However, online mentoring programs may need a variety of structural supports, such as on-going guidance for the youth, in order to be successful.

There are several limitations to this preliminary study that should be considered. First, the sample of mentors, which included some celebrities recruited by People magazine, was not representative of a typical population of mentors. Although the inclusion of some “celebrity” mentors might have somehow influenced the course and content of the relationship, it also may have infused the ties with a sense of false hope and, ultimately, disappointment. In other cases, the opportunity to engage in email exchanges with a celebrity may have generated greater enthusiasm for participating in the program than the youth might otherwise have felt.

More generally, this study is descriptive in nature and does not address the overall effectiveness of online mentoring. More in-depth examination of the nature of relationships formed through online programs and whether and what types of contributions these relationships may make to youth development is needed. This exploratory research should be followed by studies that incorporate rigorous methodology that includes control groups, random or matched participant selection, and standardized outcome measures. Within this context, it will be important to understand the nature of the relationships that are formed online, in what arenas of the youths’ lives such relationships are most likely to have a significant influence, and the level and frequency of contact that is needed to sustain mentoring ties. Carefully conducted evaluations could help determine whether e-mail mentoring relationships can ever effectively substitute for face-to-face mentoring and/or whether it is a useful adjunct. At present, most experts appear to agree that mentoring relationships that are conducted exclusively online are preferable only when face-to-face connections are unavailable, unfeasible, or inappropriate (McCurdy, 2003). Yet a more hybrid approach may, in fact, offer the best of both worlds, with online mentoring reinforcing and bridging face-to-face meetings (Ensher & Murphy, 1997).

Whether online mentoring is used alone or as an adjunct to face-to-face meetings, it will be important to redress the unacceptably high rates of early termination that emerged in this program. When programs are well conceived, supported, and structured, such relationships stand a better chance of taking hold and thriving. Mentors, mentees, and site supervisors need to be clear about the commitment they are making to each other, and mentors should be encouraged to make every effort to keep their initial commitment in order to allow the relationship time to grow. Adequate training and support should be provided to site managers so that they, in turn, can offer support to matches. Site managers should be trained to engage in ongoing quality control, assessing how well each relationship is progressing and working to help faltering relationships. Indeed, sustained site manager involvement has been identified as critical to the formation of sustainable online mentoring programs (Cravens, 2003). Guidelines that have been established for use of the Internet within the context of helping professions might be particularly useful in training staff to develop and sustain high quality online mentoring relationships (Kraus, Zack, & Stricker, 2004).

As online mentoring expands, there is a growing need for a better understanding of its complexities and the circumstances under which such programs are most effective. This includes a more refined understanding of the predictors of longevity, and the factors that explain why some relationships remain superficial while others deepen into meaningful ties. At this stage, it is difficult to discern whether online mentoring may represent an effective approach to helping youth. In some cases, online mentoring may act as a convenient and powerful means of connecting caring adults with today's youth whereas in others it may lead to misunderstandings and even increased isolation. The balance can, and should, be tipped toward the former outcome. A deeper understanding of such relationships, combined with high quality programs that incorporate the best practices of youth mentoring, will better position us to harness the potential of online mentoring.

REFERENCES

Beier, S. R., Rosenfeld, W. D., Spitalny, K. C., Zansky, S. M., & Bontempo, A. N. (2000). The potential role of an adult mentor in influencing high risk behaviors in adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 154, 327–331.

Bennett, D., Hupert, N., Tsikalas, K., Meade, T., & Honey, M. (1998). Critical issues in the design and implementation of telementoring environments. Centre for Children and Technology. Retrieved January 26, 2006, from http://www2.edc.org/CCT/admin/publications/report/09_1998.pdf.

Cravens, J. (2003). Online mentoring: Programs and suggested practices as of February 2001. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 21(1–2), 85–109.

Eccles, J. S., & Gootman, J. (2002). Community programs to promote youth development. Washinton, DC: National Academy Press.

Ensher, E. A., Heun, C., & Blanchard, A. (2003). Online mentoring and computer-mediated communication: New directions in research. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 63, 264–288.

Ensher, E., & Murphy, S. E. (1997). Effects of race, gender, perceived similarity, and contact on mentor relationships. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 50(3), 460–481.

Granovetter, M. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 73, 1361–1380.

Grossman, J. B., & Rhodes, J. E. (2002). The test of time: Predictors and effects of duration in youth mentoring programs. American Journal of Community Psychology, 30, 199–219.

Grossman, J. B., & Tierney, J. P. (1998). Does mentoring work? An impact study of the Big Brothers/Big Sisters program. Evaluation Review, 22, 403–426.

Hatcher, S. (2002). Using email with your patients. Australasian Psychiatry, 9, 207–209.

Kraus, R., Zack, J., & Stricker, G. (Eds.) (2004). Online counseling: A handbook for mental health professionals. Boston: Academic Press.

Kraut, R., Lundmark, V., Patterson, M., Kiesler, S., Mukopadhyay, T., & Scherlis, W. (1998). Internet paradox: A social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological well-being? American Psychologist, 53(9), 1017–1031.

Lieblich, A., Tuval-Mashiach, R., & Zilber, T. (1998). Narrative research: Reading, analysis, and interpretation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

McCurdy, K. G. (2003). The perceptions of supervising counselors regarding alternative methods of communication. Dissertation Abstracts International, 63(8-A). (UMI No. 2003-95003-029)

Miller, H., & Griffiths, M. (2005). E-mentoring. In D. L. DuBois & M. J. Karcher (Eds.), Handbook of youth mentoring (pp. 300–313). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Mundorf, N., & Laird, K. (2002). Social and psychological effects of information technologies and other interactive media. In J. Bryant & D. Zillmann (Eds.), Media effects: Advances in theory and research (pp. 583–602). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum Associates.

National Mentoring Center (2002). Perspectives on e-mentoring. A virtual panel holds an online dialogue. National Mentoring Center Newsletter, 9, 5–12. Retrieved January 26, 2006, from http://www.nwrel.org/mentoring/pdf/bull9.pdf.

O'Neill, D. K., Wagner, R., & Gomez, L. M. (1996). Online mentors: Experimenting in science class. Educational Leadership, 54(3), 39–42.

Parra, G. R., DuBois, D. L., Neville, H. A., & Pugh-Lilly, A. O. (2002). Mentoring relationships for youth: Investigation of a process-oriented model. Journal of Community Psychology, 30(4), 367–388.

Price, M. A., & Chen, H. H. (2003). Promises and challenges: Exploring a collaborative mentoring programme in a preservice teacher education programme. Mentoring and Tutoring, 11, 105–117.

Putnam, R. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Rheingold, H. (1993). The virtual community: Homesteading on the electronic frontier. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley.

Rhodes, J. E. (2002). Stand by me: The risks and rewards of mentoring today's youth. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Salem, D. A., Bogat, G. A., & Reid, C. (1997). Mutual help goes on-line. Journal of Community Psychology, 25(2), 189–207.

Sanchez, B., & Harris, J. (1996). Online mentoring, a success story. Learning and Leading with Technology, 23(8), 57–60.

Scealy, M., Phillips, J., & Stevenson, R. (2003). Shyness and anxiety as predictors of patterns of Internet usage. Cyberpsychology and Behavior, 5, 507–5156.

Segall, R. (2000). Online shrinks. Psychology Today, 32(3), 38–44.

Slicker, E. K., & Palmer, D. J. (1993). Mentoring at-risk high school students: Evaluation of a school-based program. The School Counselor, 40, 327–334.

Turkle, S. (1996). Virtuality and its discontents: Searching for community in cyberspace. The American Prospect, 24, 50–57.

Zimmerman, M. A., Bigenheimer, J. B., & Notaro, P. C. (2002). Natural mentors and adolescent resiliency: A study with urban youth. American Journal of Community Psychology, 30(2), 221–243.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rhodes, J.E., Spencer, R., Saito, R.N. et al. Online Mentoring: The Promise and Challenges of an Emerging Approach to Youth Development. J Primary Prevent 27, 497–513 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-006-0051-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-006-0051-y