Abstract

Objectives To assess changes in participants’ expectations about length of sick leave during Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)-based occupational rehabilitation, and whether the change in expectations was associated with future work participation. Methods Cohort study with 9 months follow-up including sick listed workers who took part in one of two randomized controlled trials. The change in expectations about length of sick leave were assessed using a test of marginal homogeneity. Furthermore, linear and logistic regression evaluated associations between changes in expectations and sustainable return to work (RTW) and work participation days. Results During rehabilitation, there was a statistically significant improvement in participants’ (n = 168) expectations about length of sick leave. During 9 months follow-up, participants with consistently positive expectations had the highest probability of RTW (0.81, 95% CI 0.67–0.95) and the most work participation days (159, 95% CI 139–180). Participants with improved expectations had higher probability of sustainable RTW (0.68, 95% CI 0.50–0.87) and more work participation days (133, 95% CI 110–156) compared to those with reduced (probability of RTW: 0.50, 95% CI 0.22–0.77; workdays: 116, 95% CI 85–148), or consistently negative expectations (probability of RTW: 0.23, 95% CI 0.15–0.31; workdays: 93, 95% CI 82–103). Conclusions During ACT-based occupational rehabilitation, 33% improved, 48% remained unaltered, and 19% of the participants reduced their expectations about RTW. Expectations about RTW can be useful to evaluate in the clinic, and as an intermediary outcome in clinical trials. The changes were associated with future work outcomes, suggesting that RTW expectations is a strong predictor for RTW.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Work disability is a vast challenge in most western countries, with musculoskeletal and mental health disorders being the leading causes [1]. Work disability is no longer considered the result of medical factors alone, but rather a combination of individual, workplace, healthcare, compensation system and social factors [2, 3]. Individuals’ expectations about length of sick leave is one individual factor that repeatedly has been associated with work outcomes [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11].

Expectations is a complex psychological construct. The most recognized underlying theoretical model is Bandura’s concept of self-efficacy [4, 5, 12], the confidence in one’s own ability to achieve intended results [12]. Positive expectations are associated with better health outcomes for a variety of different conditions ranging from myocardial infarction to psychiatric conditions [13]. The association between return to work (RTW) expectations and work participation outcomes are consistent across studies despite different ways of measuring the expectation construct [14]. The worker’s RTW expectations are influenced by physical, personal and environmental factors [15], and have proved to be a more accurate predictor of work outcomes than predictions by health professionals and insurance officers [6].

Several core components in RTW interventions for musculoskeletal complaints, like cognitive behavioral approaches, focuses on participants’ expectations [16]. It has also been suggested that occupational rehabilitation programs should target expectations directly to facilitate RTW [17, 18]. However, there are no studies assessing whether interventions succeed in changing participants’ expectations about length of sick leave.

The current study assessed whether the participants’ expectations about length of sick leave changed during occupational rehabilitation, and whether the changes in expectation were associated with future work outcomes. Our hypothesis was that participants’ RTW expectations would change positively after taking part in the rehabilitation programs and that improved expectations would be associated with increased work participation.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

A cohort study with 9 months follow-up was conducted in individuals participating in one of two randomized occupational rehabilitation trials (Fig. 1). The purpose of the randomized trials was to assess the effect on sickness absence of two different inpatient multicomponent occupational rehabilitation programs versus a less comprehensive outpatient program. The study protocol and results from one of the randomized trials have been published [19,20,21]. The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics in Central Norway (No.: 2012/1241), and the trial is registered in clinicaltrials.gov (No.: NCT01926574).

Eligible participants were aged 18–60 years, and sick listed 2–12 months with a diagnosis within the musculoskeletal (L), psychological (P) or general and unspecified (A) chapters of the ICPC-2 (International Classification of Primary Care, Second edition). If participants were on graded sick leave benefits, it had to be at least 50% (i.e. 50–100%). Exclusion criteria, assessed by a questionnaire and an outpatient screening performed by a physician, a physiotherapist and a psychologist, were: (1) alcohol or drug abuse; (2) serious somatic (e.g. cancer, unstable heart disease) or psychological disorders (e.g. high suicidal risk, psychosis, ongoing manic episode); (3) specific disorders requiring specialized treatment; (4) pregnancy; (5) currently participating in another treatment or rehabilitation program; (6) insufficient oral or written Norwegian language skills to participate in group sessions and fill out questionnaires; (7) scheduled for surgery within the next 6 months; or (8) serious problems with functioning in a group settings.

The Rehabilitation Programs

The inpatient programs consisted of group-based Acceptance and Commitment therapy (ACT) [22]—a form of cognitive behavioral therapy, individual and group-based physical training, mindfulness, education on various topics, and individual meetings with the coordinators in work-related problem-solving sessions and creating a RTW-plan. One program lasted 3.5 weeks and the other 4 + 4 days (8 days in total with 2 weeks at home in-between). The outpatient program consisted mainly of group-based ACT once a week for 6 weeks, each session lasting 2.5 h. The common component for the inpatient- and outpatient programs was ACT, where the aim was to facilitate RTW through increased psychological flexibility [23], which presumably would increase self-efficacy and RTW expectations. Participants with different diagnoses were included in the same program. This is common in occupational rehabilitation in Norway. It is also in line with studies showing that there is considerable overlap between musculoskeletal complaints and mental health problems [24, 25]. A more detailed description of the programs has been published elsewhere [21].

Questionnaires

Self-reported data on expectations about length of sick leave and other questionnaires were collected via internet-based questionnaires at the start and end of the rehabilitation programs.

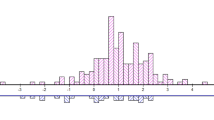

Expectations about length of sick leave were assessed with the question “For how long do you believe you will be sick listed from today?”, with the 6 response options: “not at all”, “less than 1 month”, “1–2 months”, “2–4 months”, “4–10 months” and “more than 10 months”. The first two categories; “not at all” and “less than 1 month” were combined as they were close in time and included few participants. In addition, the variable was dichotomized into positive (< 2 months) and negative (≥ 2 months) expectations. Based on these two categories respondents were classified in one of four groups according to their expectations at the start and end of rehabilitation: (1) Consistently positive, (2) Improved, (3) Reduced and (4) Consistently negative.

Participants were asked to evaluate their general health on a 4-point Likert scale from 1 “poor” to 4 “very good”. The variable was dichotomized into “poor/not very good” and “good/very good”. Other variables registered by questionnaires at the start of the rehabilitation programs were anxiety and depression symptoms (measured using The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [26]), pain (measured by one question from the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) [27]), level of education (dichotomized as high (college/university) or low) and employment status (having employment or not).

Sick Leave Register Data

Sick leave was measured using data from the Norwegian National Social Security System Registry, where all individuals receiving any form of sickness or disability benefits in Norway are registered by their social security number. Medically certified sick leave is compensated with 100% coverage for the first 12 months. After 12 months of sick leave, more long-term benefits may be offered in the form of work assessment allowance and disability pension, which both reimburse approximately 66% of the individual’s previous income. The data consisted of all individual registrations of periods with any medical benefits.

Two RTW-outcomes were constructed; (1) Sustainable RTW was defined as one month without receiving medical benefits and (2) Work participation days was measured as number of days not receiving medical benefits. Both outcomes were recorded during 9-month of follow-up after the end of the rehabilitation program. The number of work participation days was calculated from potential workdays minus days receiving medical benefits. Days on medical benefits were adjusted for graded sick leave and employment fraction. Work days was calculated based on a 5 days work week.

Statistical Analysis

To investigate whether the participants’ expectations about length of sick leave differed between the start and the end of the rehabilitation programs, each participant’s responses at the two time points (pre- vs. post-scores) were compared using the Stuart-Maxwell test of marginal homogeneity [28, 29]. This test assesses whether the distribution of a categorical measurement made at two separate time points (matched pair data) has ‘shifted’ during the time interval. Linear regression was used to assess whether change in expectations during rehabilitation was associated with work participation days and logistic regression for sustainable RTW. The main analyses, investigating associations between changes in RTW-expectations and the two RTW-measures, were adjusted for age, gender and education. In addition, the following analyses were performed: (1) without adjustment and (2) additionally adjusted for type of rehabilitation program, length of sick leave at inclusion, subjective health evaluation and employment status. The results from the regression analyses were used to estimate the predicted probability of sustainable RTW and work participation days using average adjusted predictions (i.e. predictions were made with covariates constant at their means). A sensitivity analysis was performed with adjustment for sick leave diagnosis.

In an additional sensitivity analysis, it was tested whether change in expectations (dichotomized as less or equal to/more than 2 months of sick leave) differed between the rehabilitation programs by performing a repeated measures analysis, using a random effects logit model with an interaction term for rehabilitation program and time.

p-values (two-tailed) < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Precision was assessed using 95% CI. All analyses were done using STATA 14.1 (StataCorp. 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP).

Results

Of the 334 participants in the randomized clinical trials, 168 participants (50%) answered the expectation question about length of sick leave at both the start and the end of the rehabilitation programs and were included in this study (Table 1). Sustainable RTW was achieved by 69 participants (41%) and the median number of work participation days during 9 months of follow-up was 113 [interquartile range (IQR) 64–169]. Of those who did not fill out the questionnaires (n = 166), 98 (59%) individuals achieved sustainable RTW and the median number of work participation days was 145 (IQR 73–186).

Changes in Expectations

Table 2 shows expectations about length of sick leave at the start and the end of the rehabilitation programs. There was a statistically significant change in expectations during the rehabilitation programs (Stuart–Maxwell test for marginal homogeneity, p = 0.01). In total, 56 (33%) of the participants improved their expectations during the programs, while 32 (19%) reduced their expectations about length of sick leave, i.e. expected a longer period of sick leave at the end of the program than at the start of the program. About half the participants (48%, n = 80) did not change their expectations. The change in expectations did not differ between the rehabilitation programs (interaction term for program and time, p = 0.178).

Associations Between Change in Expectations and Future Work Outcomes

Change in expectations about length of sick leave during rehabilitation was associated with both sustainable RTW and work participation days in the main analyses (p < 0.01, Table 3). Participants with negative expectations about length of sick leave (≥ 2 months) at the start of the program who improved their expectations during the program had a higher probability of achieving sustainable RTW at 9 months than those who did not change their expectations (0.68, 95% CI 0.50–0.87 vs. 0.23, 95% CI 0.15–0.31) (Table 3). They also had more work participation days (133, 95% CI 110–156 vs. 93, 95% CI 82–103) (Table 3). Participants who reduced their expectations (from positive to negative) during the program had a somewhat lower probability of RTW (0.50, 95% CI 0.22–0.77) and less work participation days (116, 95% CI 85–148). Participants who had positive expectations both at the start and end of the programs had the highest probability of RTW (0.81, 95% CI 0.67–0.95) and most work participation days (159, 95% CI 139–180).

Fully adjusted analyses slightly changed the estimates for participants with reduced expectations, but not the conclusions (Table 3). Analyses performed without adjustments showed similar results as the main analyses (Table 3). Adjusting for sick leave diagnosis also showed similar results (not showed).

Discussion

During occupational rehabilitation, 33% improved their RTW expectations, while 48% did not change their expectations and 19% reduced their expectations. Improved expectations were associated with increased probability of sustainable RTW and more work participation days during 9 months of follow-up compared to reduced expectations and unchanged negative expectations. Participants with consistently positive expectations had the highest probability of RTW and most work participation days.

These findings are in line with previous studies showing that participants’ expectations can change during an intervention [30, 31]. Skatteboe et al. [30] found that participants with musculoskeletal disorders changed their expectations regarding pain and functioning during a single specialist consultation. Moreover, Mancuso et al. [31] found that the patients’ preoperative expectations of recovery from hip and knee arthroplasties could be modified through education. However, the present study is, to our knowledge, the first study that examined whether expectations about length of sick leave changes during occupational rehabilitation.

Our finding that the improvement in RTW expectations was associated with future work outcomes is expanding on previous studies showing associations between expectations about sickness absence/RTW and future work outcomes [4, 14, 18, 32, 33]. RTW expectations are of great interest in RTW-research as they are modifiable and therefore may be targeted in interventions, for example through cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) approaches [4]. Therefore, it has been suggested that occupational rehabilitation programs should target expectations directly to facilitate RTW [17, 18]. For long-term sick listed individuals, biopsychosocial factors like self-efficacy might be more important in determining the prognosis for RTW than factors like symptom duration [34]. Outcome expectancies are thought to reflect the level of self-efficacy, but other factors like experiences, and work- and home environments might also be of importance [10]. Individuals’ expectations about RTW contain a myriad of factors. Still, as it is not known which factors that affect expectations, it is not evident how to best target them [7], and this should be investigated in future studies.

While 33% of the participants improved their expectations during the rehabilitation programs, 19% of the participants expected a longer sick leave duration at the end of the program than at start of the program. A qualitative study within one of the rehabilitation programs in this study could provide some insight as to why [35]: At the start of the program several participants expressed that they were in a rush to RTW, partly based on feeling pressured by the surroundings. Whereas towards the end, participants had a more “sober” attitude towards RTW. Unrealistic expectations about a “quick fix” expressed at the start of the program had changed towards seeing RTW as part of a long and complex process. This could explain the reduced expectations. If this change is towards a more realistic expectation, it might not necessarily be something negative, but rather an important step in a sustainable RTW-process. In addition, about half of the participants did not change their expectations during rehabilitation. However, it should be noted that as the participants had been sick listed for a long time (median sick days; 215), achieving RTW might be harder and a longer rehabilitation process could be necessary for these individuals. In addition, with the Norwegian National Social Security Office reimbursing 100% of the participants’ income during the first 12 months of sick leave there is little financial incentive for early RTW.

As trials assessing work participation outcomes require long follow-up, changes in expectations could be an intermediary measure of interest. The participants in this study took part in one of two linked randomized controlled trials that comprised three different occupational rehabilitation programs. Two of the programs were inpatient programs and more comprehensive than the third outpatient program. It could be expected that the more comprehensive programs would assist the participants more in their RTW process than the less comprehensive program. However, the change in expectations did not differ between the programs. It should be noted that as measuring change in a categorical variable is problematic (as you have to subtract one category from another) the expectation variable was dichotomized for these analyses, which result in a considerable loss of power in subsequent analyses. As questions about expectations about RTW are constructed in a multitude of ways, future research should also compare different assessments of expectations.

One of the strengths in this study is the use of high-quality register data for sickness absence, ensuring no missing data or recall bias. A limitation was that only 50% of the participants in the randomized trials filled out the expectation question at both times and could be included in the present study. Still, expectations at the start of the program were similar for those who filled out both questionnaires and those who only filled out the first one. The individuals who did not fill out both questionnaires achieved sustainable RTW to a higher degree and had more work participation days than the participants included in this study. This might indicate that the individuals included in this study struggled more with RTW than those who were not included. This should not affect the conclusion of this study, but it could underestimate the association between change in expectations and future work outcomes. Another limitation is the lack of power for subgroup analyses, e.g. 10% of the participants did not have employment in this study and only 20% were men.

Conclusion

During ACT-based occupational rehabilitation, 33% improved, 48% remained unaltered, and 19% of the participants reduced their expectations about RTW. The changes were associated with future work outcomes, suggesting that RTW expectations is a strong predictor for RTW, which can be useful to evaluate in the clinic, and as an intermediary outcome in clinical trials. Future studies should compare different RTW expectancy questions to identify question(s) with high sensitivity and power, and investigate how to improve RTW expectations in sick listed individuals.

References

OECD. Mental health and work. Paris: Mental Health and Work OECD Publishing; 2013.

Loisel P, Durand MJ, Berthelette D, Vezina N, Baril R, Gagnon D, et al. Disability prevention: new paradigm for the management of occupational back pain. Dis Manage Health Outcomes. 2001;9(7):351–360.

Schultz IZ, Stowell AW, Feuerstein M, Gatchel RJ. Models of return to work for musculoskeletal disorders. J Occup Rehabil. 2007;17(2):327–352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-007-9071-6.

Cornelius LR, van der Klink JJ, Groothoff JW, Brouwer S. Prognostic factors of long term disability due to mental disorders: a systematic review. J Occup Rehabil. 2011;21(2):259–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-010-9261-5.

Schultz IZ, Crook J, Meloche GR, Berkowitz J, Milner R, Zuberbier OA, et al. Psychosocial factors predictive of occupational low back disability: towards development of a return-to-work model. Pain. 2004;107(1–2):77–85.

Fleten N, Johnsen R, Forde OH. Length of sick leave—Why not ask the sick-listed? Sick-listed individuals predict their length of sick leave more accurately than professionals. BMC Public Health. 2004;4(1):46. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-4-46.

Carriere JS, Thibault P, Sullivan MJ. The mediating role of recovery expectancies on the relation between depression and return-to-work. J Occup Rehabil. 2015;25(2):348–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-014-9543-4.

Du Bois M, Donceel P. A screening questionnaire to predict no return to work within 3 months for low back pain claimants. Eur Spine J. 2008;17(3):380–385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-007-0567-8.

Nielsen MB, Madsen IE, Bultmann U, Christensen U, Diderichsen F, Rugulies R. Predictors of return to work in employees sick-listed with mental health problems: findings from a longitudinal study. Eur J Public Health. 2011;21(6):806–811. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckq171.

Nieuwenhuijsen K, Verbeek JH, de Boer AG, Blonk RW, van Dijk FJ. Predicting the duration of sickness absence for patients with common mental disorders in occupational health care. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006;32(1):67–74.

Aasdahl L, Pape K, Jensen C, Vasseljen O, Braathen T, Johnsen R, et al. Associations between the readiness for return to work scale and return to work: a prospective study. J Occup Rehabil. 2018;28(1):97–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-017-9705-2.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):191–215.

Mondloch MV, Cole DC, Frank JW. Does how you do depend on how you think you’ll do? A systematic review of the evidence for a relation between patients’ recovery expectations and health outcomes. CMAJ. 2001;165(2):174–179.

Laisne F, Lecomte C, Corbiere M. Biopsychosocial predictors of prognosis in musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review of the literature. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(5):355–382. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2011.591889.

Iles RA, Davidson M, Taylor NF, O’Halloran P. Systematic review of the ability of recovery expectations to predict outcomes in non-chronic non-specific low back pain. J Occup Rehabil. 2009;19(1):25–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-008-9161-0.

Costa-Black KM. Core components of return-to-work interventions. In: Loisel P, Anema J, editors. Handbook of work disability. New York: Springer; 2013. pp. 427–440.

Heijbel B, Josephson M, Jensen I, Stark S, Vingard E. Return to work expectation predicts work in chronic musculoskeletal and behavioral health disorders: prospective study with clinical implications. J Occup Rehabil. 2006;16(2):173–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-006-9016-5.

Brouwers EPM, Terluin B, Tiemens BG, Verhaak PFM. Predicting return to work in employees sick-listed due to minor mental disorders. J Occup Rehabil. 2009;19(4):323–332. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-009-9198-8.

Aasdahl L, Pape K, Vasseljen O, Johnsen R, Gismervik S, Halsteinli V, et al. Effect of inpatient multicomponent occupational rehabilitation versus less comprehensive outpatient rehabilitation on sickness absence in persons with musculoskeletal- or mental health disorders: a randomized clinical trial. J Occup Rehabil. 2018;28(1):170–179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-017-9708-z.

Aasdahl L, Pape K, Vasseljen O, Johnsen R, Gismervik S, Jensen C, et al. Effects of inpatient multicomponent occupational rehabilitation versus less comprehensive outpatient rehabilitation on somatic and mental health: secondary outcomes of a randomized clinical trial. J Occup Rehabil. 2017;27(3):456–466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-016-9679-5.

Fimland MS, Vasseljen O, Gismervik S, Rise MB, Halsteinli V, Jacobsen HB, et al. Occupational rehabilitation programs for musculoskeletal pain and common mental health disorders: study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):368. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-368.

Hayes SC, Strosahl K, Wilson KG. Acceptance and commitment therapy: an experiential approach to behavior change. New York: Guilford Press; 1999.

Hayes SC, Villatte M, Levin M, Hildebrandt M. Open, aware, and active: contextual approaches as an emerging trend in the behavioral and cognitive therapies. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2011;7:141–168. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032210-104449.

Reme SE, Tangen T, Moe T, Eriksen HR. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in sick listed chronic low back pain patients. Eur J Pain. 2011;15(10):1075–1080. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpain.2011.04.012.

Von Korff M, Crane P, Lane M, Miglioretti DL, Simon G, Saunders K, et al. Chronic spinal pain and physical-mental comorbidity in the United States: results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Pain. 2005;113(3):331–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2004.11.010.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–370.

Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994;23(2):129–138.

Stuart A. A test for homogeneity of the marginal distributions in a two-way classification. Biometrika. 1955;42(3/4):412–416.

Maxwell AE. Comparing the classification of subjects by two independent judges. Br J Psychiatry. 1970;116(535):651–655.

Skatteboe S, Roe C, Fagerland MW, Granan LP. Expectations of pain and functioning in patients with musculoskeletal disorders: a cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18(1):48. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-016-1386-z.

Mancuso CA, Graziano S, Briskie LM, Peterson MG, Pellicci PM, Salvati EA, et al. Randomized trials to modify patients’ preoperative expectations of hip and knee arthroplasties. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(2):424–431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-007-0052-z.

Reme SE, Hagen EM, Eriksen HR. Expectations, perceptions, and physiotherapy predict prolonged sick leave in subacute low back pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10:139. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-10-139.

Lovvik C, Shaw W, Overland S, Reme SE. Expectations and illness perceptions as predictors of benefit recipiency among workers with common mental disorders: secondary analysis from a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2014;4(3):e004321. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004321.

Laisne F, Lecomte C, Corbiere M. Biopsychosocial determinants of work outcomes of workers with occupational injuries receiving compensation: a prospective study. Work. 2013;44(2):117–132. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-2012-1378.

Rise MB, Gismervik SO, Johnsen R, Fimland MS. Sick-listed persons’ experiences with taking part in an in-patient occupational rehabilitation program based on acceptance and commitment therapy: a qualitative focus group interview study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):526. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-1190-8.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank project coworker Guri Helmersen for valuable assistance, Tryggve Skylstad at the Norwegian Welfare and Labor Service for providing lists of sick-listed individuals and Ola Thune at the Norwegian Welfare and Labor Service for providing sick leave data and insight to the National Social Security System Registry. The authors also thank clinicians and staff at Hysnes Rehabilitation Center and the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation at St. Olavs Hospital, and the participants who took part in the study.

Author Contributions

LA and MSF conceived the initial idea for this article. All authors contributed to developing the idea. LA and KP performed the analyses. LA wrote the first draft of the article. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the article.

Funding

The Liaison Committee between the Central Norway Regional Health Authority and the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (Grant No. 46056821); The Research Council of Norway (Grant No. 238015/H20); and allocated government funding through the Central Norway Regional Health Authority.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Marius Steiro Fimland has been employed at Hysnes Rehabilitation Center, St. Olavs Hospital. Lene Aasdahl and Marius Steiro Fimland have been employed at the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, St. Olavs Hospital. The other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aasdahl, L., Pape, K., Vasseljen, O. et al. Improved Expectations About Length of Sick Leave During Occupational Rehabilitation Is Associated with Increased Work Participation. J Occup Rehabil 29, 475–482 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-018-9808-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-018-9808-4