Abstract

Purpose We reviewed literature on the benefits of hiring people with disabilities. Increasing attention is being paid to the role of people with disabilities in the workplace. Although most research focuses on employers’ concerns, many companies are now beginning to share their successes. However, there is no synthesis of the peer-reviewed literature on the benefits of hiring people with disabilities. Methods Our team conducted a systematic review, completing comprehensive searches of seven databases from 1997 to May 2017. We selected articles for inclusion that were peer-reviewed publications, had a sample involving people with disabilities, conducted an empirical study with at least one outcome focusing on the benefits of hiring people with disabilities, and focused on competitive employment. Two reviewers independently applied the inclusion criteria, extracted the data, and rated the study quality. Results Of the 6176 studies identified in our search, 39 articles met our inclusion criteria. Findings show that benefits of hiring people with disabilities included improvements in profitability (e.g., profits and cost-effectiveness, turnover and retention, reliability and punctuality, employee loyalty, company image), competitive advantage (e.g., diverse customers, customer loyalty and satisfaction, innovation, productivity, work ethic, safety), inclusive work culture, and ability awareness. Secondary benefits for people with disabilities included improved quality of life and income, enhanced self-confidence, expanded social network, and a sense of community. Conclusions There are several benefits to hiring people with disabilities. Further research is needed to explore how benefits may vary by type of disability, industry, and job type.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

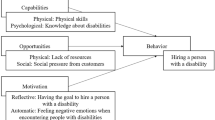

Having a diverse workforce is essential for a successful global economy [1]. A recent survey of national and multinational companies report that executives often identify disability as an area of improvement in their diversity and inclusion efforts [2]. We draw on the World Health Organization’s definition of disability, referring to it as an impairment, activity limitation, and participation restriction whereby disability and functioning are shaped by interactions between health conditions and contextual factors [3]. Indeed, demand-side employment approaches (e.g., making workplaces accessible and user-friendly), which are needed to help people with disabilities obtain employment, is gaining recognition [4, 5]. Applying such an approach shifts the focus from people with disabilities as needing services to employers and their work environments [6]. Further, this approach affects how employers respond to the needs of employees with disabilities, which can help alleviate discrimination and improve workplace integration [4]. Although many employers have concerns and misperceptions about the barriers to hiring and retaining people with disabilities [7,8,9], the literature on the successes and advantages of hiring people with disabilities is growing. Synthesizing this literature can highlight the positive aspects of including people with disabilities in the workforce and, ultimately, shift attitudes towards them.

Employment is a fundamental human right with an important value in people’s lives [10]. Increasing employment and retention of persons with disabilities is a common goal for rehabilitation professionals [8]. Specifically, participation in competitive and meaningful employment is fundamental to the physical and psychological well-being of people with and without disabilities [11]. Competitive employment refers to employment for at least 90 days in an integrated setting, performed on a full-time or part-time basis, where an individual is compensated at or above the minimum wage [11, 12]. Employment can improve quality of life, mental health, social networks, and social inclusion [13, 14]. Meanwhile, unemployment is linked with higher prevalence of depression and anxiety and lower quality of life [11].

There are currently over 18 million working-age people with disabilities in the United States (US), representing a large pool of talent [15]. Unfortunately, the employment rate is only 33% for working-age people with disabilities compared to 76% for those without disabilities [15]. Most people with disabilities would like to work but often remain unemployed or underemployed and they represent one of the largest sources of untapped talent in the labour force [7, 16,17,18,19]. About two-thirds of unemployed persons with a disability are willing to work but cannot find employment [20]. Thus, efforts to improve the inclusion of people with disabilities are needed.

This systematic review addresses several important gaps in the literature. First, reviews focusing on the employment of people with disabilities often emphasize the challenges of hiring them (e.g., [21, 22]), the discrimination experienced in the workplace (e.g., [23, 24]), or attitudes towards hiring people with disabilities (e.g., [9, 25]), and not the actual experiences of hiring them, the benefits of doing so, or companies’ successes. Second, most of the research on this topic focuses on the supply side (i.e., educational and vocational services to improve job skills and functioning) and there is a lack of attention to the demand side (i.e., employers’ behaviours and work environments). It is critical to explore demand-driven employment strategies to gain insight into the experiences of employers who actually work with people with disabilities [4]. Finally, although increased attention concentrates on the business case of hiring people with disabilities, existing literature reviews on this topic mostly concentrate on anecdotal and non-peer reviewed (i.e., grey) literature [19, 26,27,28,29]. Thus, there is a strong need to synthesize and critically appraise the peer-reviewed literature to inform evidence-based decision-making [30, 31]. Other researchers contend that a more rigorous and comprehensive systematic review is needed on this topic [9].

Methods

In this systematic review, we aim to: (1) critically appraise and synthesize the peer-reviewed evidence on the benefits of hiring people with disabilities, and (2) highlight gaps in understanding and areas for future research. We examine the empirical, peer-reviewed literature on the benefits of hiring people with disabilities. Past reviews and reports on this topic have drawn mostly on grey and non-published literature. Within our review it is critical to draw on peer-reviewed literature because the peer-review process helps to ensure the quality, relevance, integrity, and risk of bias in the published information [32,33,34]. Since grey literature does not go through the peer-review process, the quality and rigour of other past reviews and reports is uncertain and susceptible to potential conflicts of interest (e.g., practitioners evaluating interventions that they delivered) and/or to funding bias [35, 36]. Thus, peer-reviewed literature is important for evidence-informed decision-making in health care and policy/program development.

Search Strategy and Data Sources

We conducted a comprehensive search of published peer-reviewed literature using the following databases: MEDLINE, HealthStar, PsycINFO, JSTOR, Business Source Premier, Embase, and Sociological Abstracts (see Fig. 1 and Supplemental Table 1). We searched for subject headings and key terms related to disability and benefits or advantages of hiring people with disabilities (see Table 1 for full list). We searched for articles published between 1997 and May 2017. We manually examined the reference lists of all included articles to identify additional articles.

Article Selection

To select articles for this review, we applied the following inclusion and exclusion criteria. Eligibility criteria included: (1) publication in a peer-reviewed journal between 1997 and May 2017; (2) study population of people with disabilities; (3) empirical study with at least one outcome focusing on a benefit of hiring people with disabilities; and (4) focus on competitive employment. We excluded articles that: (1) were not peer-reviewed (e.g., opinion, editorial, grey literature, reports); (2) focused only on the attitudes towards or likelihood of hiring people with disabilities; (3) focused only on sheltered workshops; (4) focused only on subsidies and incentives related to hiring people with disabilities; or (5) focused only on employment rates of people with disabilities.

Our initial search identified 6176 articles for potential inclusion in this review (see Fig. 1). After removing the duplicates, two authors independently reviewed the titles and abstracts for inclusion. 3812 abstracts did not meet our inclusion criteria. We read the remaining 141 articles and independently applied the inclusion criteria. We included five additional articles identified by manually reviewing the reference lists. Thirty-nine studies met our inclusion criteria. We maintained a log of inclusion and exclusion decisions to provide an audit trail and resolved any discrepancies through discussion amongst the team.

Data Abstraction and Synthesis

The first author extracted and compiled the data from the 39 articles selected for review using a structured abstraction form. She abstracted relevant information on each study (i.e., author, year and country of publication, recruitment setting, methods, and findings). Three authors reviewed all 39 articles and the abstracted data for accuracy. We noted the limitations and risk of bias of each study.

A meta-analysis was not feasible for this review because of the heterogeneity of the studies reviewed (i.e., range of disability types, study populations, and outcome measures). Therefore, we synthesized our findings according to the guidelines for narrative synthesis [37]. This method of data abstraction and synthesis is considered relevant for reviews involving studies with diverse methodologies [37]. This method involves a structured interrogation and summary of all studies included in the review. First, we organized the studies into logical categories to guide our analysis. Second, we conducted a within-study analysis through a narrative description of each study’s findings and quality. Third, we conducted a cross-study synthesis to produce a summary of study findings while considering the variations in study design and quality [37]. After we completed the data abstraction, we discussed any discrepancies.

Methodological Quality Assessment

Our findings and recommendations for future research are based on the overall strength and quality of the evidence reviewed. The measure of bias and quality assessments were based on Kmet’s [38] standard quality and risk of bias across both qualitative and quantitative studies. Five reviewers independently applied a 14-item checklist for quantitative studies and a 10-item checklist for qualitative studies [38]. These checklists allowed for a common approach to assess study quality. The total score for each study is an indicator of strength of evidence (i.e., higher scores indicate higher study quality). The results of the quality assessment are in Supplemental Tables 2 and 3. We did not exclude any studies from our review based on quality. We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA), a method of transparent reporting (see Supplemental Table 4) [39].

Results

Study and Participant Characteristics

Thirty-nine articles met the inclusion criteria (see Table 2). Twenty-four studies were conducted in the US, five in Australia, five in Canada, and one each in Brazil, Israel, Lithuania, Netherlands, and Turkey. A wide range of methods were used across the studies including surveys (n = 12), qualitative interviews (n = 10), secondary analysis of database (n = 6), case study (n = 5), Delphi study (n = 1), mixed methods (n = 3), and focus groups (n = 2). Sample sizes ranged from 1 to 104,213 and included perspectives from employers, managers, human resource managers, employees, and customers. Most studies’ participants included several disability types (n = 22), while others focused on specific types such as intellectual impairment (n = 3), autism (n = 2), vision impairment (n = 2), hearing impairment (n = 2), developmental disability (n = 2), and severe mental illness (n = 1). It is important to note that five studies did not report participants’ type of disability.

The following industry sectors were involved: various (several) industry types within each study (n = 14), hospitality (n = 6), food service (n = 2), supermarkets (n = 2), and one each in cleaning, logistics, healthcare, footwear, business process outsourcing, non-profit, and telecommunications. Seven studies did not identify the industry sector. Specific job types were often not reported in the studies. Furthermore, very few studies incorporated a theoretical framework. Of those that did, they included normalization and social role valorization [68], social contact theory [69], theory of other [44], the social servicescape model [45], and theory of resource-based competitive advantage [47, 51].

Outcome and Study Findings

Although the outcome measures varied greatly across the studies we reviewed, all studies reported at least one benefit of hiring people with disabilities (see Table 1). Findings show that benefits of including people with disabilities involved improvements in profitability (i.e., profits and cost-effectiveness, turnover and retention, reliability and punctuality, employee loyalty, company image), competitive advantage (i.e., diverse customers, customer loyalty and satisfaction, innovation, productivity, work ethic, safety), inclusive work culture, and ability awareness.

Profitability

Profits and Cost-Effectiveness

Six studies reported improved profits as a result of hiring people with disabilities [8, 18, 40, 50, 55, 70]. For example, Buciuniene and Kazlauskaite [18] described that supermarkets hiring people with disabilities (various types) had increased sales. Hartnett et al. [8] and Schartz et al. [40] both found that perceived benefits of workplace accommodations for people with various types of disabilities helped to increase profits, especially through cost savings of not having to re-hire and re-train new workers. Kalargyrou and Volis [70], who studied employers in the hospitality industry, found that hiring people with various types of disabilities improved profits and increased business growth, although they did not specify how. In Wolffe and Candela’s [50] study, they interviewed nine employers from large, non-profit companies who hired people with vision impairments and noted improved sales resulting from including such workers. Zivolich and Weiner-Zivolich [55], in a longitudinal survey of 14,000 employees in the hospitality industry, found that hiring people with disabilities, the majority of whom had cognitive impairments, helped to increase profits. One company reported over $19 million in financial benefits, mainly in the form of tax credits, over a 6-year period, and an additional savings of $8.4 million on recruitment and training due to improved retention [55].

Three studies reported the cost-effectiveness of hiring people with disabilities [52, 57, 60]. For example, Cimera [57] analyzed an administrative rehabilitation services database and found that supporting employees (i.e., through a vocational rehabilitation program) with intellectual disabilities had a benefit-cost ratio of 1.21. In a similar study, Cimera and Burgess [52] discovered that hiring people with autism was cost-effective, with an average benefit-cost ratio of 5.28. Moreover, Graffam et al. [60], in a survey of 643 employers from various industries, found that 70% of employers identified more benefits associated with hiring people with disabilities rather than costs, especially related to training costs. They also found the employee’s impact on the work environment rated significantly better [60].

Two studies [56, 61] described a community economic benefit to hiring people with disabilities. For example, Zivolich [55] estimated the economic benefit to the community of hiring people with disabilities at over $12 million in the form of taxes paid by new workers with disabilities. They also explained that taxpayers saved an additional $43 million resulting from reduced social welfare payments and rehabilitation costs [56]. Similarly, Eggleton et al.’s study [61] showed that hiring people with intellectual disabilities was economically beneficial to the community because employment was a cheaper alternative to income and welfare support measures.

Turnover and Retention

Other components of profitability include employee retention and turnover. Eight studies in our review reported that hiring people with disabilities improved retention and reduced turnover [8, 18, 25, 48, 49, 53, 55, 63]. For example, in Adams-Scollenberger and Mitchell’s [53] study on janitors with intellectual disabilities, they had a significantly higher retention rate compared to workers without a disability (34% compared to 10% after 1 year). Buciuniene and Kazlauskaite’s [18] study discovered that although turnover is a common problem in the supermarket industry, it was 20–30% lower at supermarkets employing people with disabilities. They also noted that turnover of other employees without disabilities at these stores was lower than the industry average [18]. Gen-qing and Qu’s [48] survey of 500 employers in the food service industry showed that people with various types of disabilities had a lower turnover rate than people without disabilities. Zivolich and Weiner-Zivolich [55] found one national restaurant chain saved more than $8 million over a 6-year period due to reduced turnover rates after hiring people with disabilities. Moreover, people with disabilities in retail and hospitality sectors had longer job tenure compared to those without disabilities (23.7 and 50 months longer, respectively); however, it is important to note these differences were not significant [25]. In Kalargyrou’s study [49] of the retail sector, the turnover rate was similarly lower for people with disabilities compared to those without disabilities (15–16% compared to 55%, respectively). Kaletta et al.’s [63] descriptive case study on Walgreens’ supply chain and logistics division indicated that people without a disability had a significantly higher turnover rate compared to employees with a disability. Further, Hartnett et al. [8] noted that providing accommodations to employees with a disability reduced turnover and increased retention rates.

Reliability and Punctuality

Eleven studies found that people with disabilities were reliable and/or punctual employees [5, 40, 41, 48,49,50, 59, 60, 63, 65, 70]. For example, Graffam et al. [60] conducted a large survey across various industries and reported that people with disabilities were significantly more reliable than workers without disabilities (i.e., average of 8.3 days absent for people with disabilities compared to 9.7 days absent for people without disabilities). In the hospitality sector, Hernandez et al. [5] found employees with disabilities had 1.24 fewer days absent compared to workers without disabilities. Hindle et al. [59] discovered that employees with a disability from a large metropolitan call centre were significantly longer serving than employees without a disability.

Two studies [49, 70] focusing on employees with disabilities in the hospitality and retail industry found that they had good attendance. In another study, a telecommunications company found reductions in sick leave absences for all employees—with and without disabilities [64]. For example, sick leave rates for the whole company ranged from 6.25 to 7.8%, whereas the sick leave rate for the branch with people with disabilities ranged from 3.5 to 4.8% [64]. Further, employees with disabilities took 73% less time off work than other employees [63]. Similarly, in the food service industry, people with disabilities were punctual and dependable [48]. Meanwhile, others reported that people with vision impairments were very dedicated workers [50]. Morgan and Alexander [65] found that people with disabilities had consistent attendance, which was one of the most frequently identified advantages of hiring them. Further, providing accommodations to people with disabilities improved attendance [40].

Employee Loyalty

Loyalty is related to employee turnover and dedication. Six studies reported that people with disabilities are loyal employees [18, 41, 42, 48, 49, 70] For example, Buciuniene and Kazlauskaite [18] found that employees with disabilities working in supermarkets were highly loyal, more so than employees without disabilities, because they showed gratitude and displayed lower turnover rates. In the food service industry [48], and leisure and hospitality industry [53] employers rated employees with disabilities most positively in terms of loyalty and punctuality. Nietupski et al. [41] found that the highest ranked benefit of hiring employees with disabilities across a variety of industries was employee dedication, where employers perceived people with disabilities as dedicated and loyal workers. Kalargyrou [49] suggested that the loyalty of people with disabilities is because they are often not given many opportunities to work and to live an independent life.

Company Image

Five studies reported that hiring people with disabilities improved business image [8, 41, 67, 70, 71]. For example, Harnett et al. [8] found an improved company image as a result of hiring people with various types of disabilities. Kalargyrou and Volis [70] noted that employees with disabilities in the hospitality sector created a positive company image. Among workers with hearing impairments in a coffee shop chain, employers reported they added value to the company, especially through enhancing their image of caring and inclusivity [67]. Similarly, having deaf workers in the business process outsourcing sector helped improve company image and corporate social responsibility [71].

Competitive Advantage

Three studies focused on competitive advantage as a benefit of hiring people with disabilities [49, 54, 70]. For example, Rosenbaum et al. [54], in their survey of 100 customers in the restaurant industry, found that restaurants who hired people with vision impairments to be frontline employees gained a competitive advantage over establishments that did not. Case studies conducted with managers across various industries confirmed that hiring people with disabilities resulted in increased competitive advantage [49]. They attributed this improvement to having a pool of loyal employees that exceeded expectations, had lower turnover rates, and performed better in terms of attendance and employee engagement [49]. In a similar study, Kalargyrou and Volis [70] found a competitive advantage of including people with disabilities because it created a positive image for guests.

Diverse Customers

Three studies described increased competitive advantage as a result of improved customer diversity [1, 18, 40]. For example, Buciuniene and Kazlauskaite [18] reported a more diversified customer base as a result of hiring people with disabilities. Specifically, employers noticed that more customers with disabilities began shopping at the stores with employees with disabilities to interact with them [18]. Moreover, in Schartz et al.’s [40] survey of 890 employers, 15% attributed their enhanced customer base to employing people with disabilities. In Henry et al.’s [1] study, employers recognized that people with disabilities represent an important customer base and that there is an opportunity for companies to win brand loyalty among a broad market of customers who value inclusion [1].

Customer Loyalty/Satisfaction

Eight studies reported benefits on customer loyalty and/or satisfaction related to hiring people with disabilities [43, 54, 55, 60, 62, 64, 66, 70]. This increased satisfaction was found across studies focusing on hospitality [43, 54, 55, 62, 70], telecommunication [64], and other various industries [66]. Types of disabilities included vision impairments [54], intellectual disability [55], and other various disabilities.

Innovation Skills

Three studies noted people with disabilities’ innovation and creative skills as a benefit of hiring them [46, 70, 71]. For instance, employers viewed people with hearing impairments in the business process outsourcing industry as creative [71]. In the hospitality sector, employees with disabilities helped create innovative services [70]. Meanwhile, Scott et al. [46] examined employees with autism and highlighted their different abilities, including creative skills.

Productivity

Nine studies reported productivity as a benefit to hiring people with disabilities [8, 40, 43, 49, 58, 60, 63, 71]. In a study of various disability types across different industries, 61% of employers considered productivity as a benefit of hiring people with disabilities [60]. In the hospitality industry, the majority of employers reported that people with disabilities could be as productive as any other employee [43]. Similarly, Kaletta et al. [63] found workers with and without disabilities were equally productive in the supply and logistics chain division of Walgreens. Bitencourt and Guimaraes [58] found a perceived improvement in productivity among employees with mental illness in a footwear company. Friedner [71] described that employees with hearing impairments were productive workers with excellent work habits. In the hospitality and retail industry, Kalargyrou [49] noted that employees with disabilities helped improve workplace productivity. Two studies found an overall increase in company productivity with the presence of employees with disabilities [40, 72]. Three studies showed that providing accommodations to employees with disabilities helped productivity [8, 40, 72].

Work Ethic

Four studies reported a strong work ethic among those who are deaf and those with autism [41, 46, 71, 73]. Scott et al. [46], in a survey of employers who hired people with autism, described that employees with autism performed at an above standard level with regards to attention to detail and work ethic. Similarly, Friedner [71] found that employees with hearing impairments had strong work ethic, performing beyond their job functions. Irvine [73] found that people with developmental disabilities were dedicated, hardworking, and efficient. Meanwhile, Nietupski et al. [41] described that employees with various disabilities were also dedicated and efficient workers.

Safety

Four studies found that the presence of employees with disabilities improved workplace safety [40, 49, 55, 63]. For example, Kalargyrou [49] reported that physical and psychological safety (i.e., the culture and support from the company that creates the best conditions for people with and without disabilities to work side by side) improved in the hospitality and retail industry with the presence of people with disabilities. In a similar industry, Kaletta et al. [63] reported that people with disabilities had 34% fewer accidents than other employees. People with cognitive impairments in the hospitality industry also had an above average safety record [55]. Further, Schartz et al. [40] showed that providing workplace accommodations to people with disabilities improved workplace safety.

Inclusive/Diverse Work Culture

Another beneficial outcome of hiring people with disabilities involved an inclusive and diverse workplace culture, as reported in 14 studies [1, 5, 8, 18, 40, 46, 50, 55, 58, 64, 65, 70, 74, 75]. For example, Buciuinene and Kazlauskaite [18] found that providing (dis)ability awareness training for co-workers of employees with disabilities created a more inclusive workplace culture, which can strengthen a company’s overall workforce [1]. A benefit of hiring people with disabilities included the diversification of work settings which can lead to an overall inclusive and positive work environment [5]. Kalef et al. [64] found that hiring people with disabilities in a telecommunications company helped to create an inclusive workplace culture and to improve co-worker partnerships [65]. Owen et al. [74] noted that having people with developmental disabilities in the workforce facilitated the enhancement of social inclusion and workplace well-being. Similarly, Scott et al. [46] found that the presence of employees with autism encouraged the development of a more inclusive workplace culture. Schartz et al. [40] and Solovieva et al. [75] both reported that providing workplace accommodations improved co-worker interactions. In Wolffe and Candela’s [50] study of people with vision impairments in large non-profit companies, they found improved workplace inclusion by having a mentor/buddy system. Bitencourt and Guimaraes [58] described the 6-step inclusion process implemented by a footwear company: (1) identify and evaluate tasks performed in the company, (2) inform and prepare staff to work with people with disabilities, (3) brief the worker with a disability, (4) train them through engagement of their skills and limitations, (5) integrate and support them, and (6) regular monitoring and quarterly reviews. Zivolich and Weiner-Zivolich [55] found that having workers with disabilities (mainly cognitive impairments) in the hospitality industry helped improve workplace culture.

Improved morale was another component of an enhanced workplace culture attributed to the presence of employees with disabilities, as reported in seven studies [8, 40, 46, 55, 66, 72, 75]. A further two studies found that workers with disabilities increased workplace motivation and engagement [67, 70].

Increased Ability Awareness

Increased awareness of the abilities of people with disabilities was a main advantage of hiring them [7, 8, 18, 46, 55]. For example, Buciuniene and Kazlauskaite [18] found that having employees with disabilities in supermarkets increased public awareness of their abilities. Similarly, in Scott et al.’s [46] study, having employees with autism increased awareness about the condition. Hartnett et al. [8] noted improved recognition among employees of the value of people with disabilities. Zivolich and Weiner-Zivolich [55] reported an increase in community recognition and an improved corporate culture from hiring people with disabilities. Furthermore, managers who worked with disabled youth in summer placements said that the experience challenged their stereotypes and misperceptions about people with disabilities [7].

Secondary Benefits

Secondary outcomes included benefits for people with disabilities themselves such as improved quality of life [61], enhanced self-confidence [18, 73, 74, 76], a source of earnings or income [77, 78], an expanded social network [78], and a sense of a community [78].

Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias

We noted limitations within each of the studies that were included in this review. Three reviewers independently rated each study using Kmet’s standard quality assessment [38]. The overall scores for the quantitative studies ranged from 0.4 to 0.91 (mean 0.76) (Supplemental Table S3). For inter-rater agreement, reviewers assigned the same overall score to 80% of the studies. The majority of the discrepancies reflected the extent of the applicability of certain items (i.e., assignment of “yes” vs. “partial” criteria fulfilment). These discrepancies were discussed until consensus was reached. For the qualitative studies, the scores ranged from 0.3 to 0.85 (average 0.67) with 85% inter-rater agreement (Supplemental Table S2).

Regarding the quality of the studies and risk of bias within each study, there is a critical need for more rigorously designed research with standardized measures and representative samples. Areas of the Kmet [38] quality assessment where quantitative studies scored lower included description of subject characteristics, estimate of variance for main results, and control for confounding factors. For the qualitative studies, areas scoring lower included not having a connection to a theoretical framework, lacking a description of the sampling strategy and data analysis, lack of a verification procedure, and not being reflexivity of the account.

Most of the studies had heterogeneous samples and did not specify the types of disability, sample demographic characteristics, or job roles, which could affect the perceived benefits of hiring people with disabilities. When type of employment was reported, it was mainly entry-level type work. Some studies had small samples sizes or were limited to specific industries; thus, their findings are not generalizable. Further, most studies focused on perceived benefits rather than actual benefits.

Risk of Bias Across the Studies

It is important to consider the risk of bias across the studies within our review. Although our search was comprehensive, it is possible that eligible studies were missed. First, not all of the studies contributed equally to the overall summary of the findings. We felt it was important to include all relevant studies to contribute to a comprehensive understanding of the benefits of hiring people with disabilities. Second, the studies included in this review involved various types of disability and caution should be taken in generalizing the findings. Third, there were different outcome measures used in the included studies which affected our ability to make comparisons among them. Fourth, many of the studies did not report on the demographic characteristics of the people with disabilities (e.g., age, gender, education, work experience) or the nature of their job roles which could impact their productivity and commitment to the workplace. Future studies should explore this further.

Discussion and Conclusions

Exploring the benefits of hiring people with disabilities is important because they face many barriers in finding and maintaining employment, and bringing attention to the benefits of hiring people with disabilities may help build the case for employing them and providing them with proper accommodations. Our findings suggest that hiring people with disabilities can improve profitability (e.g., profits and cost-effectiveness, turnover and retention, reliability and punctuality, employee loyalty, company image). Employees with various disabilities were reported to be more punctual, reliable, and conscientious in their work which translated to increased productivity and, ultimately, improved company profitability [8]. Reasons for improved profitability and lower turnover rates included the sense of accomplishment and satisfaction employees with disabilities received from employment and the sense of loyalty they felt towards the companies that invested in recruiting and training them [49]. Employees with disabilities were recognized as reliable, punctual, and having low turnover rates specifically in service industries such as hospitality, grocery and food service, and retail [25, 41, 49, 63, 70]. This may be due to the fact that these industries are more likely to hire individuals with disabilities than goods-producing companies or other industries [79].

Our findings show that hiring people with disabilities can enhance competitive advantage (e.g., diverse customers, customer loyalty and satisfaction, innovation, productivity, work ethic, safety) in certain industries such as hospitality, food service, and retail as well as in other various industries. Siperstein et al. [66] reported on a national study showing that 92% of consumers felt more favorable towards companies hiring individuals with disabilities and that 87% would prefer to give their business to organizations employing individuals with disabilities. This is consistent with the findings in our review claiming that hiring people with disabilities offered a competitive advantage within and outside of the company. Houtenville and Kalargyrou [42] stated that human capital (e.g., loyalty, training, relationships) is one of the main sources of competitive advantage for a company and its reputation among customers, suppliers, and employees, which could explain the increase in competitive advantage in these studies. The industries that most commonly reported enhanced competitive advantage were the hospitality and service industries [18, 49, 54, 55, 70]. This can be attributed to employees with disabilities dealing with customers face-to-face which creates more opportunities to increase customer loyalty, especially among customers who value inclusion and diversity [1, 62]. Another trend was that employees who were deaf or who had autism spectrum disorder were seen as creative, innovative, and having a strong work ethic and attention to detail [46, 67, 71]. This finding is consistent with literature on individuals with autism in the workforce [80].

Our findings suggest that hiring people with disabilities can create a more inclusive work culture and increase ability awareness. Companies hiring individuals with intellectual disabilities reported improvements in workplace social connection, in the company’s public image and diversity, and in employees’ acceptance of and knowledge about people with disabilities [42, 81]. The benefits of increased ability awareness included improved performance of employees, increased psychological safety and trust in the workplace, and a positive effect on company products and services by making them more inclusive to customers/clients [2, 49]. Disability inclusion and awareness is important in employment because this helps employers to effectively manage and work with people with disabilities and normalizes an employment model of hiring individuals of all abilities [49]. A trend found among several studies was that improved inclusion, workplace culture, and ability awareness were associated with a company’s ability to provide proper accommodations or disability training for all employees [1, 18, 40, 50, 58]. This highlights the importance of informing employers of proper training and accommodation procedures [82].

Secondary benefits of employment for people with disabilities included improved quality of life, enhanced self-confidence, a source of income, an expanded social network, and a sense of a community. These findings show consistency with other literature focusing on the experiences of people with disabilities in the workplace [6, 15, 18].

Overall, the majority of the studies focused mostly on profitability and much less so on the actual inclusion of people with disabilities in the workforce. Employers should make a concerted effort to ensure that people with disabilities feel included. (Dis)ability awareness and sensitivity training can help with this [83].

Future Research

Overall, there is a strong need for more rigorous research on the benefits of hiring people with disabilities. Future research should focus on several areas. First, more focus is needed on the inclusion and quality of life of and benefits for people with disabilities, particularly from their experiences. Second, employees with disabilities’ level of education, training, and employment experience and their type of employment was generally not reported in the studies that we reviewed. Future studies should explore how these and other demographic factors influence the benefits of hiring people with disabilities. Third, there is a need to study whether specific types of disability and certain job roles affect outcomes. Fourth, a greater understanding of how people with disabilities influence profits inside and outside of the company (e.g., larger community and societal benefits) is needed. Fifth, of the studies that reported on the type of job held by people with disabilities, they mainly consisted of entry-level (minimum wage) positions. Further work is needed to explore the inclusion and benefits of hiring people with disabilities in professional positions (e.g., upper management, leadership roles). It is important to explore the differences in workplace inclusion among individuals with different disability types (e.g., physical, intellectual, mental, non-visible and visible disabilities) and the specific barriers and facilitators they face. Finally, although many employers have good intentions, future studies should address the concern that some employers may take advantage of people with disabilities (e.g., hiring them for tax incentives). Companies may be motivated by the improvements to their corporate image that result from hiring people with disabilities rather than focusing on the disability management or benefits of employees with disabilities [84].

Limitations

There are several limitations of this review. First, the specific databases and search terms that we selected for our search strategy may have limited our ability to find relevant publications. We did, however, design our search in consultation with an experienced librarian and experts in the field. Second, policies, tax incentives, and societal attitudes towards people with disabilities vary greatly by country and across time. Therefore, the findings should be interpreted accordingly. Finally, we only chose studies published in English and in peer-reviewed journals; thus, some publications may have been missed.

We identified several limitations in the studies we reviewed. First, many of the studies had small and heterogeneous samples. Second, the studies used a wide variety of standardized and unstandardized outcome measures which limited our ability to compare effectiveness across studies. Third, the mean age of the sample and other important demographic characteristics, such as type, severity and cause of disability (e.g., acquired, work-related injury) and age at onset, were not provided. Such factors can affect engagement in employment [85] (e.g., younger samples may still be in school and not have as much time to work). Third, many studies did not describe the type of work that people with disabilities were engaged in (i.e., job roles and industries), nor the extent of supports they may have received within their job, which likely vary greatly by country. Other studies only focused on one industry type, site, and/or region. Thus, caution should be used in generalizing the findings across job roles and industries. Fourth, most studies did not report effect sizes and did not have comparison groups. Fifth, most studies did not describe the educational level, extent of job experience, and hours worked of employees with disabilities, which are important factors in employment outcomes. Sixth, many studies focused on perceived benefits (i.e., self-report/anecdotes) rather than providing rigorous evidence. Seventh, several studies reported differences between people with disabilities and those without a disability (e.g., higher/lower) but did not run significance tests. Finally, many studies reported on employees’ perceptions without actually asking them (i.e., making assumptions about their experiences).

References

Henry AD, Petkauskos K, Stanislawzyk J, Vogt J. Employer-recommended strategies to increase opportunities for people with disabilities. J Vocat Rehabil. 2014;41(3):237–248.

Forbes Insights. Global diversity and inclusion: fostering innovation through a diverse workforce. New York: Forbes Insight; 2011.

World Health Organization. Disabilities. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. http://www.who.int/topics/disabilities/en/.

Huang I-C, Chen RK. Employing people with disabilities in the taiwanese workplace: employers’ perceptions and considerations. Rehabil Couns Bul. 2015;59(1):43–54.

Hernandez B, McDonald K, Divilbiss M, Horin E, Velcoff J, Donoso O. Reflections from employers on the disabled workforce: focus groups with healthcare, hospitality and retail administrators. Empl Responsib Rights J. 2008;20(3):157–164.

Gilbride D, Stensrud R, Vandergoot D, Golden K. Identification of the characteristics of work environments and employers open to hiring and accommodating people with disabilities. Rehabil Couns Bull. 2003;46(3):130–137.

Lindsay S, McDougall C, Sanford R. Exploring supervisors’ attitudes of working with youth engaged in an inclusive employment training program. J Hum Dev Disabil Soc Change. 2014;20(3):12–20.

Hartnett HP, Stuart H, Thurman H, Loy B, Batiste LC. Employers’ perceptions of the benefits of workplace accommodations: reasons to hire, retain and promote people with disabilities. J Vocat Rehabil. 2011;34(1):17–23.

Burke J, Bezyak J, Fraser RT, Pete J, Ditchman N, Chan F. Employers’ attitudes towards hiring and retaining people with disabilities: a review of the literature. Aust J Rehabil Couns. 2013;19(1):21–38.

UN General Assembly. Universal declaration of human rights. UN General Assembly 1948.

Dutta A, Gervey R, Chan F, Chou C-C, Ditchman N. Vocational rehabilitation services and employment outcomes for people with disabilities: a United States study. J Occup Rehabil. 2008;18(4):326–334.

Rehabilitation Services Administration. Reporting manual for the case service report (RSA-911). Washington, DC: RSA; 2004. Report No.: RSA-PD-04-04.

Evans J, Repper J. Employment, social inclusion and mental health. J Psychiatr Mental Health Nurs. 2000;7(1):15–24.

Dunstan DA, Falconer AK, Price IR. The relationship between hope, social inclusion, and mental wellbeing in supported employment. Aust J Rehabil Couns. 2017;23(01):37–51.

Erickson W, Lee C, Von Schrader S. Disability status report: United states. Ithaca: Cornell University Employment and Disability Institute (EDI); 2012.

Livermore GA, Goodman N, Wright D. Social security disability beneficiaries: characteristics, work activity, and use of services. J Vocat Rehabil. 2007;27(2):85–93.

Green JH, Brooke V. Recruiting and retaining the best from america’s largest untapped talent pool. J Vocat Rehabil. 2001;16(2):83–88.

Buciuniene I, Bleijenbergh I, Kazlauskaite R. Integrating people with disability into the workforce: the case of a retail chain. Equal Divers Incl Int J. 2010; 29(5):534–538.

Allen J, Cohen N. The road to inclusion: integrating people with disabilities into the workplace. Toronto: Deloitte; 2010.

National Council on Disability. Empowerment for Americans with disabilities: breaking barriers to careers and full employment. Washington, DC: National Council on Disability; 2007.

Unger DD. Workplace supports: a view from employers who have hired supported employees. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabil. 1999;14(3):167–179.

Kaye HS, Jans LH, Jones EC. Why don’t employers hire and retain workers with disabilities? J Occup Rehabil. 2011;21(4):526–536.

Lindsay S. Discrimination and other barriers to employment for teens and young adults with disabilities. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(15–16):1340–1350.

McMahon BT, Shaw LR, West S, Waid-Ebbs K. Workplace discrimination and spinal cord injury: the national eeoc ada research project. J Vocat Rehabil. 2005;23(3):155–162.

Hernandez B, McDonald K. Exploring the costs and benefits of workers with disabilities. J Rehabil. 2010;76(3):15–23.

Business Council of Australia. Improving employment participation of people with disabilities. 2013.

Equity and Diversity Directorate Policy Branch. Recruitment of persons with disabilities: a literature review. Ottawa, ON: Public Service Commission of Canada; 2011.

Fredeen K, Martin K, Birch G, Wafer M. Rethinking disability in the private sector. Panel on Labour Market Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities, 2013. p. 28.

Human Resources and Skill Development Canada. Advancing the inclusion of people with disabilities. Gatineau: HRSDC; 2009.

Khan K, Kunz R, Kleijnen J, Antes G. Systematic reviews to support evidence-based medicine. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2011.

Baarends E, Van der Klink M, Thomas A. An exploratory study on the teaching of evidence-based decision making. Open J Occup Ther. 2017;5(3):8–20.

Doncliff B. The peer-review process in scholarly writing. Whitireia Nurs Health J. 2016;(23):55–60.

Connelly LM. Peer review. MedSurg Nursing. 2017;26(6):146–147.

Kreiman J. On peer review. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2016;59(3):480–483.

Bellefontaine SP, Lee CM. Between black and white: examining grey literature in meta-analyses of psychological research. J Child Fam Stud. 2014;23(8):1378–1388.

Adams J, Hillier-Brown FC, Moore HJ, Lake AA, Araujo-Soares V, White M, et al. Searching and synthesising ‘grey literature’ and ‘grey information’ in public health: critical reflections on three case studies. Syst Rev. 2016;5(164):1–11.

Petticrew M, Roberts H. Systematic reviews in the social sciences: a practical guide. Oxford: Wiley; 2008.

Kmet LM, Lee RC, Cook LS. Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. Edmonton: Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research; 2004.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The prisma statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100.

Schartz HA, Hendricks D, Blanck P. Workplace accommodations: evidence based outcomes. Work 2006;27(4):345–354.

Nietupski J, Hamre-Nietupski S, VanderHart NS, Fishback K. Employer perceptions of the benefits and concerns of supported employment. Educ Train Mental Retard Dev Disabil. 1996;31(4):310–323.

Houtenville A, Kalargyrou V. People with disabilities. Cornell Hosp Q. 2011;53(1):40–52.

Bengisu M, Balta S. Employment of the workforce with disabilities in the hospitality industry. J Sustain Tour. 2011;19(1):35–57.

Levinas E. Totalité et infini essai sur l’extériorité. La Haye: Nijhoff; 1961.

Bitner MJ. Servicescapes: the impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. J Mark 1992;56(2):57–71.

Scott M, Jacob A, Hendrie D, Parsons R, Girdler S, Falkmer T, et al. Employers’ perception of the costs and the benefits of hiring individuals with autism spectrum disorder in open employment in australia. PLoS ONE 2017;12(5):e0177607. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177607.

Grant RM. The resource-based theory of competitive advantage: implications for strategy formulation. Calif Manag Rev. 1991;33(3):114–135.

Chi CG-Q, Qu H. Integrating persons with disabilities into the work force. Int J Hosp Tour Adm. 2003;4(4):59–83.

Kalargyrou V. Gaining a competitive advantage with disability inclusion initiatives. J Hum Resour Hosp Tour. 2014;13(2):120–145.

Wolffe K, Candela A. A qualitative analysis of employers’ experiences with visually impaired workers. J Vis Impair Blind 2002;96(9):1200–1204.

Barney J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J Manag. 1991;17(1):99–120.

Cimera RE, Burgess S. Do adults with autism benefit monetarily from working in their communities? J Vocat Rehabil. 2011;34(3):173–180.

Adams-Shollenberger GE, Mitchell TE. A comparison of janitorial workers with mental retardation and their non-disabled peers on retention and absenteeism. J Rehabil. 1996;62(3):56–61.

Rosenbaum MS, Baniya R, Seger-Guttmann T. Customer responses towards disabled frontline employees. Int J Retail Distrib Manag. 2017;45(4):385–403.

Zivolich S, Weiner-Zivolich JS. A national corporate employment initiative for persons with severe disabilities: a 10-year perspective. J Vocat Rehabil. 1997;8(1):75–87.

Zivolich S, Shueman SA, Weiner JS. An exploratory cost-benefit analysis of natural support strategies in the employment of people with severe disabilities. J Vocat Rehabil. 1997;8(3):211–221.

Cimera RE. National cost efficiency of supported employees with intellectual disabilities: 2002 to 2007. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2010;115(1):19–29.

Bitencourt RS, Guimaraes LB. Inclusion of people with disabilities in the production system of a footwear industry. Work 2012;41(Suppl 1):4767–4774.

Hindle K, Gibson B, David A. Optimising employee ability in small firms: employing people with a disability. Small Enterp Res. 2010;17(2):207–212.

Graffam J, Smith K, Shinkfield A, Polzin U. Employer benefits and costs of employing a person with a disability. J Vocat Rehabil. 2002;17(4):251–263.

Eggleton I, Robertson S, Ryan J, Kober R. The impact of employment on the quality of life of people with an intellectual disability. J Vocat Rehabil. 1999;13(2):95–107.

Kuo P-J, Kalargyrou V. Consumers’ perspectives on service staff with disabilities in the hospitality industry. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag. 2014;26(2):164–182.

Kaletta JP, Binks DJ, Robinson R. Creating an inclusive workplace: integrating employees with disabilities into a distribution center environment. Prof Saf. 2012;57(6):62–71.

Kalef L, Barrera M, Heymann J. Developing inclusive employment: lessons from telenor open mind. Work. 2014;48(3):423–434.

Morgan RL, Alexander M. The employer’s perception: employment of individuals with developmental disabilities. J Vocat Rehabil. 2005;23(1):39–49.

Siperstein GN, Romano N, Mohler A, Parker R. A national survey of consumer attitudes towards companies that hire people with disabilities. J Vocat Rehabil. 2006;24(1):3–9.

Friedner M. Producing “silent brewmasters”: deaf workers and added value in India’s coffee cafés. Anthropol Work Rev. 2013;34(1):39–50.

Wolfensberger W. Social role valorization: a proposed new term for the principle of normalization. Mental Retard. 1983;21(6):234–239.

Allport G. The nature of prejudice. Reading: Addison-Wesley; 1954.

Kalargyrou V, Volis AA. Disability inclusion initiatives in the hospitality industry: an exploratory study of industry leaders. J Hum Resour Hosp Tour. 2014;13(4):430–454.

Friedner M. Deaf bodies and corporate bodies: new regimes of value in Bangalore’s business process outsourcing sector. J Roy Anthropol Inst. 2015;21(2):313–329.

Solovieva TI, Dowler DL, Walls RT. Employer benefits from making workplace accommodations. Disabil Health J. 2011;4(1):39–45.

Irvine A, Lupart J. Into the workforce: employers’ perspectives of inclusion. Dev Disabil Bull. 2008;36:225–250.

Owen F, Li J, Whittingham L, Hope J, Bishop C, Readhead A, et al. Social return on investment of an innovative employment option for persons with developmental disabilities. Nonprofit Manag Leadersh. 2015;26(2):209–228.

Solovieva TI, Walls RT, Hendricks DJ, Dowler DL. Cost of workplace accommodations for individuals with disabilities: with or without personal assistance services. Disabil Health J. 2009;2(4):196–205.

Blessing LA, Jamieson J. Employing persons with a developmental disability: effects of previous experience. Can J Rehabil. 1999;12:211–221.

Clark RE, Xie H, Becker DR, Drake RE. Benefits and costs of supported employment from three perspectives. J Behav Health Serv Res. 1998;25(1):22–34.

Kuiper L, Bakker M, Van der Klink J. The role of human values and relations in the employment of people with work-relevant disabilities. Soc Incl. 2016;4(4):176.

Houtenville A, Kalargyrou V. Employers’ perspectives about employing people with disabilities: a comparative study across industries. Cornell Hosp Q. 2015;56(2):168–179.

Hagner D, Cooney BF. “I do that for everybody”: supervising employees with autism. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabil. 2005;20(2):91–97.

Lysaght R, Ouellette-Kuntz H, Lin C-J. Untapped potential: perspectives on the employment of people with intellectual disability. Work 2012;41(4):409–422.

Nota L, Santilli S, Ginevra MC, Soresi S. Employer attitudes towards the work inclusion of people with disability. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2014;27(6):511–520.

Phillips BN, Deiches J, Morrison B, Chan F, Bezyak JL. Disability diversity training in the workplace: systematic review and future directions. J Occup Rehabil. 2016;26(3):264–275.

Dibben P, James P, Cunningham I, Smythe D. Employers and employees with disabilities in the UK: an economically beneficial relationship? Int J Soc Econ. 2002;29(6):453–467.

Ramos R, Jenny G, Bauer G. Age-related effects of job characteristics on burnout and work engagement. Occup Med. 2016;66(3):230–237.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Ontario Ministry of Research and Innovation and the Kimmel Matching Fund. They did not play any role in the design nor writing of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Ontario Ministry of Research and Innovation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lindsay, S., Cagliostro, E., Albarico, M. et al. A Systematic Review of the Benefits of Hiring People with Disabilities. J Occup Rehabil 28, 634–655 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-018-9756-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-018-9756-z