Abstract

Objective To examine the impact of the social workplace system on sustained return-to-work (SRTW). Methods A random sample of workers’ compensation claimants was recruited to complete a survey following claim acceptance (baseline), and 6 months later (time 2). SRTW, at baseline and time 2, was classified as those reporting being back at work for >28 days. Co-worker and supervisor support were assessed using five and seven items, respectively, and total scores were produced. A list of potential supervisory and co-worker reactions were presented to participants who were asked whether the reaction applied to them; response were coded as positive or non-positive. Demographic and injury characteristics, and work context factors were collected. Baseline and at time 2 multivariable models were conducted to examine the impact of supervisory and coworker support and injury reaction on SRTW. Results 551 (baseline) and 403 (time 2) participants from the overall cohort met study eligibility criteria. At baseline, 59% of all participants indicated SRTW; 70% reported SRTW at time 2. Participants reported moderate support from their supervisor (mean = 8.5 ± 3.9; median = 8.2; range = 5–15) and co-workers (mean = 10.2 ± 4.5; median = 10.3; range = 5–25). Over half reported a positive supervisor (59%) or co-worker injury reaction (71%). Multivariable models found that a positive supervisor injury reaction was significantly associated with SRTW at baseline (OR 2.3; 95% CI 1.4–3.9) and time 2 (OR 1.6; 95% CI 1.1–2.3). Conclusions Promoting supervisor positivity towards an injured worker is an important organizational work disability management strategy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

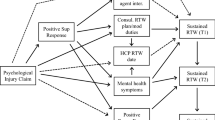

The workplace has been described as a social system, made up of diverse actors that all play an important role in the management and prevention of work disability [1,2,3,4]. Within the workplace social system, a growing body of research indicates that the attitudes of supervisors and co-workers and the assistance they provide to an injured worker can encourage early and sustained return-to-work (SRTW) [3,4,5]. Notably, evidence regarding the impact of supervisor and co-worker social support on the management of work disability has been mixed, with few studies focusing solely on social dynamics within the workplace [6, 7]. This longitudinal study aims at further unpacking the impact of the workplace social system on SRTW.

Supervisors are integral to the day-to-day management of work disability in organizations. Studies have attributed the importance of supervisors to their close proximity to frontline workers and awareness of social dynamics in the workplace [8, 9]. Within the context of work re-entry following injury, supervisors are often a first point of contact, they translate corporate disability management policies to their supervisees and implement and monitor modified duties [10,11,12]. Cross-sectional research of workers with musculoskeletal (MSK) and psychological injuries have indicated that supervisors who are empathetic and offer instrumental (e.g., assistance with tasks or offers of accommodations), emotional (e.g., reassurance) or informational (e.g., advice) dimensions of social support to an injured employee provide a foundation for successful work reintegration and build SRTW readiness and encourage requests for job accommodations [4, 6, 7, 13, 14]. More recently, interventions have targeted building competencies among supervisors in managing work disability and communicating with injured workers. In a randomized controlled trial, both workers with back pain and their supervisors were administered a training program that enhanced communication and problem-solving skills with regards to workplace pain management [11]. The training program contributed to few differences in pain severity. However, attributed to strengthened supervisors-employee relationships, workers in the treatment group were less likely to access health care to manage their back pain, reported a significant decline in the number of sickness absences, and were more likely to indicate greater perceived health [11]. Despite the importance of supervisors in managing work disability, there is a paucity of longitudinal studies that have examined how social support and attitudes can impact the SRTW of a worker following a physical or psychological injury.

Co-workers also shape daily working experiences and interact directly with injured colleagues during work reintegration [15]. Interestingly, research indicates that a bulk of responsibilities related to disability management often gets informally distributed to co-workers in the form of additional job responsibilities or overseeing modified work arrangements [16,17,18]. At the same time, co-workers often do not receive training on work reintegration practice or are not formally considered in the planning and implementation of organizational work disability management policies and programs [18, 19]. Qualitative studies of the workplace social context show that a negative co-worker reaction and lower workplace social support following an injury can contribute to prolonged work disability [5]. Similarly, a systems-based model of the work re-entry process has also found that a negative co-worker response to a work injury can reduce levels of social support within an organizational system, decrease the rate of work reintegration, and dampen the effectiveness of organizational work disability management policies and procedures [3]. When compared to supervisors, it is unclear whether co-worker social support and reaction towards an injury are more or less important to SRTW.

Through an analysis of a longitudinal cohort of workers’ compensation claimants in Victoria, Australia, this study aims at examining the social workplace system and its impact on SRTW. In particular, we examine worker perceptions of supervisor and co-worker social support prior to an injury, and supervisor and co-worker reactions following work injury, and their association with SRTW at two study time points. We hypothesize that greater perceived workplace social support and a positive reaction by both supervisors and co-workers will be related to a greater likelihood of SRTW. We also hypothesize that the relationship between perceived social support and positive injury reactions and SRTW will not significantly differ when comparing supervisors to co-workers.

Methods

Study Context and Recruitment

Data were collected as part of a longitudinal study aimed at examining the factors associated with RTW in a cohort of WorkSafe Victoria (WSV) compensation claimants in Victoria, Australia. WSV covers approximately 85% of the labour market in Victoria for wage replacement and health care expenditures associated with physical and psychological (mental) workplace injuries [20, 21]. Standard workers’ compensation claims in Victoria are those with 10 or more days of work absence attributed to a workplace injury, with the employer covering the first 10 days of absence.

The initial study sample was recruited over a 12-month period. Each month, WSV identified a random sample of claimants with MSK and psychological injuries who had their workers’ compensation claim accepted in the previous month using WSV’s internal system for classifying the nature of injury/disease [22]. Each potential participant was sent a primary approach letter with the option to opt-out of the study over the following 3-week period by contacting WSV. Contact details of claimants who did not opt out were then provided to an external interviewing agency to invite each claimant to participate in the study. Participant exclusions included sickness absence of <10 days, multiple injuries, or being aged <18 years. Participants were recruited as soon as possible after their claim was accepted (baseline). Contact with claimants was attempted for a 2-month period, after which time the claimant was considered not contactable. The nature of injury was confirmed verbally at the start of each interview. 6 months following the baseline survey, participants were contacted for a subsequent interview (time 2). The study protocol was approved by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee.

Questionnaire

All participants were administered a telephone-based questionnaire which asked a combination of questions regarding a participant’s injury, as well as demographic and work context characteristics. Questions were adapted from previous cohort studies of RTW [23], and developed in consultation with stakeholders with experience in RTW.

Outcome Measure

Sustained Return-to-Work (SRTW)

We utilized a working status question that asked whether a claimant was back at work following their injury including pre-injury job roles or modified duties [24]. Participants were also asked about whether RTW was sustained for 28 days or longer. Respondent’s SRTW status was captured in the baseline and time 2 interviews.

Independent Variables

Social support and injury reaction were examined at baseline as two important dimensions of the workplace social system.

Co-worker and supervisor social support prior to injury was examined at baseline. Participants were asked about situations where they required support at work, not in relation to their injury. Five questions were posed on co-worker support (e.g., “Was there good co-operation between the co-workers at work?”) and three questions on supervisor support (e.g., “Did you get help and support from your nearest supervisor?”) (1 = always; 5 = never). Questions were summed to produce an overall score reflecting the absence of support, with a higher score reflecting less supportiveness.

Supervisor/Co-worker Injury Reaction

At baseline, participants were presented with eight specific supervisory reactions to their injury including blame, support, anger, sympathy, disbelief, promotion of early work reentry, no reaction and discouragement of injury reporting. Also, participants were presented with five reactions that their co-workers might have had to their injury including sympathy, absence of sympathy, frustration, concern, support and no reaction. Participants were asked if the reaction was applicable to their work disability experience (1 = yes; 0 = no) [23]. The research team initially coded responses as positive, mixed, neutral, or negative reactions. To enable comparative analyses while sustaining statistical power, responses were dichotomized into two categories, positive and non-positive (i.e., neutral, mixed or negative reactions).

Covariates

Demographic, injury and work context factors were collected at baseline. Those selected for study inclusion have been found to be associated with the workplace social system and RTW in previous research [23].

Demographic and Injury Characteristics at Baseline

Details on age (years), gender, injury type (i.e., musculoskeletal or mental health injury), self-perceived injury severity (5 = very severe; 1 = very slightly severe), and time since injury (months) were collected.

Work Context Factors at Time of Injury

Employment characteristics including whether an individual was employed full-time (>30 h/week) versus part-time (<30 h/week), holding permanent versus temporary employment (e.g., casual, seasonal, contract), and in shift work versus traditional daytime scheduling. Information on job tenure (months), and whether or not a workplace was unionized was also collected. Participants were also asked to rate the frequency (1 = never; 5 = always) with which their job included exposure to five physical (e.g., lifting/bending/pulling heavy objects, repetitive tasks, working in awkward positions) and six mental job demands (e.g., unachievable deadlines, working intensely, fast work pace). Responses to physical and mental demand items were summed to produce a total score ranging from 5 to 25 and 5 to 30, respectively [25]. Pre-injury job autonomy was examined using the Work Autonomy Scale [26]. Participants were asked about the extent to which they agreed or disagreed to five statements regarding job control and autonomy (e.g., “I was allowed to decide how to go about getting my job done”, “I had control over the scheduling of my work”) (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). Items were totalled to produce a score out of 25 [26].

Analyses

Several analyses were undertaken. All analyses were restricted to participants who reported having a supervisor and co-worker. First, descriptive statistics were used to build a profile of respondents and to examine distributions of study variables. Second, bivariate analyses (i.e., analyses of variance and Chi square tests) were performed to examine the relationship between workplace social support and supervisor/co-worker reaction to injury. Bivariate analyses were also conducted to examine the association between study variables and SRTW. We conducted three separate multivariable logistic regression models at baseline and at time 2 to examine the impact of the workplace social system on SRTW that adjusted for demographic, injury and work context covariates—model 1 examined supervisor and co-worker reactions to injury; model 2 examined perceived workplace social support; and model 3 examined a combination of workplace social support and reaction to injury. The decision to conduct separate models enabled us to examine the independent and joint effects of injury reaction and workplace support on SRTW. Utilizing a stepwise procedure, covariates that had no impact on the point estimates of workplace social support and reaction to injury (p > .05), were retained in the models with a threshold of p < .05. All analyses were carried out using SAS 9.3 [27].

Results

A sample of 869 claimants was reached by the external interviewing agency, met eligibility criteria, and agreed to participate in the study; 629 respondents completed the time 2 survey. The final sample represents, 36% of the eligible sample of claimants, and 49% of the sample where contact was made. Close to 40% of all participants who were recruited, were reached between 3 and 4 months following first time of incapacity (median days between interview and incapacity = 110). Of those who completed the survey, 551 (baseline) and 403 (time 2) had a supervisor and/or co-worker in their place of employment and no missing data on relevant study covariates.

Just over half of participants (57%) were aged 35–54 years and female (51%). Almost three quarters (74%) reported a musculoskeletal injury and 44% reported being off of work <2 months as a result of their injury. At baseline, 76% of participants were employed full-time and most (83%) indicated job tenure >12 months. More than 88% of respondents indicated being in permanent employment, 40% reported shift work, and 70% worked in small- to medium-sized companies (<99 employees). Fewer than 40% of participants were employed in a non-unionized workplace. Participants tended to indicate a mean physical demands score of 10.8 out of a possible 25 points (±5.5), and a mental job demands score of 16.2 out of a possible 30 points (±6.0). Respondents also indicated a job autonomy score of 13.5 out of a possible 25 points (±5.2) (Table 1).

Participants reported moderate pre-injury support from their supervisor (mean = 8.5 ± 3.9; median = 8.2; range = 5–15) and co-workers (mean = 10.2 ± 4.5; median = 10.3; range = 5–25). Both supervisor and co-worker social support were normally distributed. Over half of participants (59%) reported a positive reaction from their supervisors to their injury, and 72% indicated a positive co-worker reaction to work injury (Table 1). Bivariate analyses uncovered interrelationships between workplace social system factors (Table 2). Notably, greater perceived supervisor and co-worker social support was significantly associated with both positive supervisor and co-worker reaction to work injury.

SRTW outcomes at baseline and time 2 are presented on Table 3, and compared across workplace social system factors. At baseline, 59% of all participants indicated SRTW, and 70% reported SRTW at time 2. Those reporting greater supervisor and co-worker social support were significantly more likely to report SRTW at baseline and time 2. Similarly, participants indicating a positive supervisor and co-worker response to injury were significantly more likely to report SRTW at baseline and time 2 when compared to those reporting a non-positive response to injury.

Results of adjusted multivariable logistic models are presented on Table 4. Models examined injury reaction (model 1), workplace social support (model 2), and both injury reaction and workplace social support (model 3) as primary independent variables related to SRTW. All models at baseline were adjusted for demographic (e.g., gender, age), injury characteristics (e.g., injury type, time since injury), and work context covariates (e.g., mental demands, and job autonomy). The time 2 models were adjusted for same set of covariates, as well as baseline SRTW. Findings from the fully adjusted baseline model (model 3), indicated that a positive supervisor reaction to an injury was significantly associated with SRTW (OR 2.3; 95% CI 1.4–3.9). A significant relationship between supervisor reaction and SRTW was also found when examining SRTW at time 2 (OR 1.6; 95% CI 1.1–2.3). However, this finding was only uncovered in the model that did not include injury reaction (model 1). A series of subgroup analyses were also performed to examine if model findings would differ by injury type, company size, unionization and gender. Results from sensitivity analyses showed no statistically significant differences.

Discussion

The workplace social system plays an important role in the sustained reintegration of injured workers. Through a longitudinal cohort study of compensation claimants in Victoria, Australia, our findings showed that a worker’s perceptions regarding their supervisor’s initial reaction to a workplace injury was significantly related to SRTW at baseline. The findings underscore the need to focus on the social system in the design of organizational work disability management policies and programs, with a specific consideration of the strategies that promote an early positive supervisor response to work injuries.

Interestingly, our study found that participants indicated moderate perceptions of workplace support prior to their injury, and over half received a positive reaction from their co-workers and supervisors following an injury. A significant relationship between workplace social support, injury reaction, and SRTW was uncovered. A positive reaction towards an injured worker may reflect pre-existing supportive supervisor and co-worker relationships that are also more likely to lead to offers of assistance with work reintegration following an injury [3, 16,17,18]. Our study adds to a body of research regarding the importance of an organizational culture that fosters SRTW. Previous research has found that organizational cultures characterized by greater cooperation, trust, and information sharing are more likely to have a lower incidence of and length of lost-time claims [28]. As an extension, results from this study may suggest that an organizational culture which is perceived by the worker to have greater supportiveness and positivity towards injured workers may also be important to improving sustained work reentry.

Consistent with a growing body of previous literature, we found that supervisors play a particularly important role in facilitating SRTW. Multivariable analyses indicated that a positive supervisor reaction to an injured worker was significantly related to SRTW at baseline. After adjusting for baseline RTW and study covariates at time 2, the relationship between supervisor reaction and SRTW was non-significant. The ways in which supervisors react may communicate the nature of relationships and the degree of goodwill within a workplace [8, 9]. Supervisors, who communicate positive messages following an injury, may be those that are able to effectively convey support and direct the resources necessary to facilitate early and sustained RTW. Our study adds to growing literature on the role of optimizing supervisory communication practices as a way to strengthen work disability management [10,11,12, 29]. Additional research is needed to understand opportunities to enhance the framing and delivery of messages following work disability so that they are perceived as positive by injured workers and effectively facilitate SRTW.

Results also underscore the need to encourage supervisor positivity towards work injury as a strategy to promote SRTW. Drawing from previous research on workplace social dynamics, a positive reaction may encourage injured workers to engage in a dialogue with their supervisor throughout the RTW process about their limitations and needs [13, 30]. On the other hand, encouraging positivity may not be straightforward, especially in organizational contexts characterized by high physical and psychological demands or low job security [5]. In these types of work environments, supervisors often report barriers to managing work disability (e.g., time constraints, job pressures, or an absence of training) that may also play a role in the level of positivity conveyed towards an injured worker [4, 10, 13, 29]. Promoting a favorable reaction may also be difficult for supervisors who have disabled workers with invisible signs and symptoms that are less recognizable and complicated to understand and/or accommodate [31,32,33]. Research is required to examine the role employer policies play in facilitating or hindering dialogue that fosters work reentry, and understand the strategies that different organizations can use to encourage a positive supervisor response to workplace injuries.

In contrast to our hypotheses, co-workers may have less of a role in the RTW process when considering supervisor support and injury reaction. Previous research finds that co-workers shape work experiences and can influence management of work disability within organizations [5, 15, 18]. Results from the multivariable analyses conducted in our study found that co-worker injury reaction and support were not significantly associated with SRTW at baseline or time 2. Findings may reflect the significant bivariate relationship that existed between co-worker and supervisor injury reaction and support, and potential shared variance in the model. At the same time, findings could also suggest that co-workers are perceived as having less influence on SRTW in relation to supervisors who have more authority over workplace policies and practices. Results could also reflect minimal training provided to co-workers in disability management and their inability to offer the level of support that is effective for SRTW [18, 19]. Given their close proximity to injured workers during the return-to-work process, there may be a need for additional research to examine the role of co-workers in organizational work disability management programs. Additional social network and systems-level analyses within organizations could be helpful to provide a better understanding of workplace relationships, as well as the nature and frequency of RTW conversations [3].

Strengths of our study include a large cohort of compensation claimants representing those experiencing different injuries, and a range of demographic and work context characteristics. We were also successfully able to measure SRTW at two time points following an injury, and to examine perceptions of co-worker and supervisor social support and injury reactions. One limitation of our survey may be attributed to the time lag between participant injury, recruitment, and interview. Close to 40% of participants completed the baseline survey 3–4 months following first time of incapacity. While we controlled for time since injury in each model, respondents may have experienced recall bias when describing their work disability experience and supervisor/co-worker injury reaction. Additional research could also be necessary to examine potential factors that mediate the relationship between injury reaction and SRTW. Lastly, our examination of co-worker and supervisor support was based on five and three items, respectively. Subsequent studies could draw from diverse measures to capture more details on emotional, instrumental and informational dimensions of support offered to injured workers [34].

The workplace social system plays an important role in the management of work disability. Our longitudinal study of compensation claimants in Victoria, Australia indicated that the supervisor reaction to a work injury was important to the RTW process where a positive reaction may reflect levels of support in the workplace that encourage early and sustained RTW. Organizations should pay special attention to social dynamics within a workplace when designing and implementing work disability policies and practices, and should consider ways in which they can foster support and positivity towards injured workers.

References

MacEachen E, Kosny A, Ferrier S, Chambers L. The “toxic dose” of system problems: why some injured workers don’t return to work as expected. J Occup Rehabil. 2010;20(3):349–366.

Loisel P, Durand P, Abenhaim L, Gosselin L, Simard R, Turcotte J, et al. Management of occupational back pain: the Sherbrooke model. Results of a pilot and feasibility study. Occup Environ Med. 1994;51(9):597–602.

Jetha A, Pransky G, Fish J, Hettinger LJ. Return-to-work within a complex and dynamic organizational work disability system. J Occup Rehabil. 2016;26(3):276–285.

Shaw WS, Robertson MM, Pransky G, McLellan RK. Employee perspectives on the role of supervisors to prevent workplace disability after injuries. J Occup Rehabil. 2003;13(3):129–142.

Kosny A, Lifshen M, Pugliese D, Majesky G, Kramer D, Steenstra I, et al. Buddies in bad times? The role of co-workers after a work-related injury. J Occup Rehabil. 2013;23(3):438–449.

Campbell P, Wynne-Jones G, Muller S, Dunn KM. The influence of employment social support for risk and prognosis in nonspecific back pain: a systematic review and critical synthesis. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2013;86(2):119–137.

Nieuwenhuijsen K, Bruinvels D, Frings-Dresen M. Psychosocial work environment and stress-related disorders, a systematic review. Occup Med. 2010;60(4):277–286.

Nordqvist C, Holmqvist C, Alexanderson K. Views of laypersons on the role employers play in return to work when sick-listed. J Occup Rehabil. 2003;13(1):11–20.

MacEachen E, Clarke J, Franche R-L, Irvin E. Systematic review of the qualitative literature on return to work after injury. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006;32(4):257–269.

Cunningham C, Doody C, Blake C. Managing low back pain: knowledge and attitudes of hospital managers. Occup Med. 2008;58(4):282–288.

Linton SJ, Boersma K, Traczyk M, Shaw W, Nicholas M. Early workplace communication and problem solving to prevent back disability: results of a randomized controlled trial among high-risk workers and their supervisors. J Occup Rehabil. 2016;26(2):150–159.

Nieuwenhuijsen K, Verbeek J, De Boer A, Blonk R, Van Dijk F. Supervisory behaviour as a predictor of return to work in employees absent from work due to mental health problems. Occup Environ Med. 2004;61(10):817–823.

McLellan RK, Pransky G, Shaw WS. Disability management training for supervisors: a pilot intervention program. J Occup Rehabil. 2001;11(1):33–41.

Aas RW, Ellingsen KL, Lindøe P, Möller A. Leadership qualities in the return to work process: a content analysis. J Occup Rehabil. 2008;18(4):335–346.

Chiaburu DS, Harrison DA. Do peers make the place? Conceptual synthesis and meta-analysis of coworker effects on perceptions, attitudes, OCBs, and performance. J Appl Psychol. 2008;93(5):1082–1103.

Baril R, Clarke J, Friesen M, Stock S, Cole D. Management of return-to-work programs for workers with musculoskeletal disorders: a qualitative study in three Canadian provinces. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(11):2101–2114.

Schminke M, Ambrose ML, Neubaum DO. The effect of leader moral development on ethical climate and employee attitudes. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 2005;97(2):135–151.

Dunstan DA, MacEachen E. Bearing the brunt: co-workers’ experiences of work reintegration processes. J Occup Rehabil. 2013;23(1):44–54.

Tjulin Å, Maceachen E, Ekberg K. Exploring the meaning of early contact in return-to-work from workplace actors’ perspective. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(2):137–145.

Safe Work Australia. Comparison of workers’ compensation arrangements in Australia and New Zealand. Canberra: Safe Work Australia; 2011.

Pearce D, Dubey M. Australian workers’ compensation law and its application: psychological injury claims. Canberra: Safe Work Australia; 2006.

Work Safe Victoria. VCode: The nature of injury/disease classification system for Victoria. Victoria: WorkSafe; 2016. https://www.worksafe.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/212394/ISBN-Vcode-the-nature-of-injury-disease-classification-sys-vic-2008-07.pdf. Accessed 31 Mar 2017.

Cole D, Mondloch M, Hogg-Johnson S, Early Claimant Cohort Prognostic Modelling Group. Listening to injured workers: how recovery expectations predict outcomes—a prospective study. CMAJ. 2002;166(6):749–754.

Franche R-L, Corbière M, Lee H, Breslin FC, Hepburn CG. Readiness for return-to-work (RRTW) scale: development and validation of a self-report staging scale in lost-time claimants with musculoskeletal disorders. J Occup Rehabil. 2007;17(3):450–472.

Lerner D, Amick BCI, Rogers WH, Malspeis S, Bungay K, Cynn D. The work limitations questionnaire. Med Care. 2001;39(1):72–85.

Breaugh JA. The measurement of work autonomy. Human Relat. 1985;38(6):551–570.

SAS Institute Inc. SAS 9.3. Version 9.3 ed. Cary: SAS Institute Inc.; 2013.

Amick B III, Habeck R, Hunt A, Fossel A, Chapin A, Keller R, et al. Measuring the impact of organizational behaviors on work disability prevention and management. J Occup Rehabil. 2000;10(1):21–38.

Shaw W, Kristman V, Vézina N. Workplace issues. In: Loisel P, Anema JR, editors. Handbook of work disability. New York: Springer; 2013. p. 163–182.

Linton SJ. The manager’s role in employees’ successful return to work following back injury. Work Stress. 1991;5(3):189–195.

Smith JM, Institute for Work & Health. Prognosis of musculoskeletal disorders: effects of legitimacy and job vulnerability. Toronto, ON: Institute for Work & Health; 1998.

Smith J, Tarasuk V, Ferrier S, Shannon H. Relationship between workers’ reports of problems of legitimacy and vulnerability in the workplace and duration on benefits for lost-time musculoskeletal injuries. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;143(11):S17, p. 66.

Krause N, Lund T. Returning to work after occupational injury. The psychology of workplace safety. Washington DC: APA Books; 2004. p. 265–295.

Peeters MC, Buunk BP, Schaufeli WB. Social interactions and feelings of inferiority. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1995;25(12):1073–1089.

Acknowledgements

This study is funded by Australian Research Council (ARC) and Institute for Safety, Compensation and Recovery Research (ISCRR). The authors would also like to acknowledge the Social Research Centre (SRC) for conducting study interviews. Also, we would acknowledge the assistance of WorkSafe Victoria, SafeWork Australia, Office of The Age Discrimination Commissioner, Beyond Blue and the Australian Industry Group.

Funding

This study is funded by the Australian Research Council and Institute for Safety, Compensation and Recovery Research awarded to PS (LP130100091).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AJ led analytical procedures and manuscript development. PS is the principal investigator for the study, and led the conceptualization, development and design of the study protocol. He critically reviewed and revised the manuscript and significantly contributed to the analysis. ADL, RL, MS, SHJ were involved in the development of the study protocol, acquisition of research funding, and manuscript development.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jetha, A., LaMontagne, A.D., Lilley, R. et al. Workplace Social System and Sustained Return-to-Work: A Study of Supervisor and Co-worker Supportiveness and Injury Reaction. J Occup Rehabil 28, 486–494 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-017-9724-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-017-9724-z