Abstract

Purpose Fear of stigma may lead employees to choose not to disclose a mental disorder in the workplace, thereby limiting help-seeking through workplace accommodation. Research suggests that various factors are considered in making decisions related to disclosure of concealable stigmatizing attributes, yet limited literature explores such decision-making in the context of mental disorder and work. The purpose of this grounded theory study was to develop a model of disclosure specific to mental health issues in a work context. Methods In-depth interviews were conducted with 13 employees of a post-secondary educational institution in Canada. Data were analyzed according to grounded theory methods through processes of open, selective, and theoretical coding. Results Findings indicated that employees begin from a default position of nondisclosure that is attributable to fear of being stigmatized in the workplace as a result of the mental disorder. In order to move from the default position, employees need a reason to disclose. The decision-making process itself is a risk–benefit analysis, during which employees weigh risks and benefits within the existing context as they assess it. The model identifies that fear of stigmatization is one of the problems with disclosure at work and describes the disclosure decision-making process. Conclusions Understanding of how employees make decisions about disclosure in the workplace may inform organizational policies, practices, and programs to improve the experiences of individuals diagnosed with a mental disorder at work. The findings suggest possible intervention strategies in education, policy, and culture for reducing stigma of mental disorders in the workplace.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

For the many people who are employed and diagnosed with a mental disorder in Canada, legislation such as the Canadian Human Rights Act (1977), the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (1982), the Employment Equity Act of Canada (1995), and the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (2005) is in place to assist them in successfully performing their roles and protect them against discrimination in employment [1]. Such legislation is not unique to Canada. For example, in the US the Americans with Disabilities Act (1990) seeks to provide similar protection to individuals with disabilities, including mental disorders. However, claiming the provisions of this type of legislation requires disclosure, at least to some extent, of the mental disorder to the employer, and employees may choose not to disclose for fear of stigmatization and its negative consequences [2, 3]. Lack of disclosure limits opportunities for workplace accommodation that could assist employees diagnosed with a mental disorder in maintaining performance in their roles and remaining in the workplace while seeking treatment and recovery [4–9]. Limitation of opportunities for recovery affects the bottom line for employers in terms of lost productivity and disability claims costs [10].

Individuals who possess a stigmatizing attribute that is concealable often live in constant fear of being discovered, and significant stress results from seeking to keep the attribute hidden and making decisions about disclosure [11, 12]. Research has clearly linked the fear of stigma to nondisclosure of concealable stigmatizing attributes [11–15]. If employees are expending considerable mental energy in identity management and seeking to conceal a mental health issue, less mental energy is available for work-related tasks [16]. The purpose of this paper is to present a theory of decision-making related to disclosure of a mental disorder at work developed through research with employees diagnosed with a mental disorder, and to discuss implications of this theory for organizations seeking to reduce stigma in their workplaces.

Background

Individuals diagnosed with a mental disorder are in fact twice stigmatized through labels of disability and mental illness [17]. Employment rates for people with disabilities remain low [18], and individuals who take a medical leave of absence become tainted by that label [19, 20]. Beardwood et al. [19] posited that attitudes towards injured workers and/or employees who take a medical leave of absence are characterized by “blame and marginalization…hidden beneath the rhetoric of return to work and rehabilitation” (p. 30). Research has found that mental disorders are more highly stigmatized than physical disorders [21]. For example, Britt [22] conducted a study that found that military personnel felt more stigmatized by screening positive for a psychological issue than a physical health issue, and perceived stigmatization was heightened when screening was conducted in front of the individual’s unit as opposed to in front of personnel that were not in the unit. This is not simply an artifact of military life. Lai et al. [23] conducted research with 300 participants diagnosed with schizophrenia or depression, and found a significant difference in perceptions of stigmatization compared to a control group of 50 cardiac patients.

Social identity theory [24] posits that individuals possess individual and group identities, and looks specifically at the relationship between self and group in terms of self-conception within group membership, group processes, and intergroup relations [25]. Stigma, as a social psychological construct that only achieves meaning within social interactions [26], results in a devalued personal social identity in group contexts such as the workplace. Although the individual will arguably always possess the attribute in question (e.g., mental disorder), stigma exists in the categorization of the individual by others as part of a devalued group [11, 27]. Disclosure decisions rest on whether to deploy the stigmatized social identity [28]. Thus identity management—the strict control of information related to the stigmatizing attribute—becomes a central concern, one influenced by fears of stigmatization and psychological needs for authenticity and legitimacy [14, 29].

While considerable literature exists related to disclosure of stigmatizing attributes, the literature related to decision-making is more limited (see e.g., [29–32]). Much of this literature has documented reasons for and against disclosure (e.g., [33, 34]). For example, a recent systematic review on disclosure of a mental disorder in the workplace documented a range of reasons for disclosure and nondisclosure, including expectations and experiences of discrimination [35]. Previous work on disclosure decision-making has developed theoretical models based on the literature (e.g., [29, 31, 36]), but in these cases has not been specific regarding the stigmatizing attribute (e.g., not exclusive to mental disorder). Research by Hudson [37] testing one theoretical model [31] with college students with invisible stigmatizing identities, including mental illness, learning disability, low socio-economic status, and lesbian, gay or bisexual orientation found that the type of stigmatized identity was important to the disclosure process (i.e., the process was different for different groups of students). Prior empirical studies have been based on samples with HIV/AIDS (e.g., [30, 32]) and have not been specific to the work context.

More recently, an ongoing research program in the United Kingdom (CORAL: Conceal or Reveal) has developed a decision aid to assist individuals in making decisions about disclosure at work [38]. In the CORAL conceptual model, disclosure decision-making is based on the theory of planned behaviour [39], and is framed as the product of disclosure values and disclosure needs. CORAL [38] hypothesized that disclosure values would be influenced by perceived and experienced stigma, self-stigma, and experienced discrimination. These constructs would influence attitudes and normative beliefs. Disclosure needs were hypothesized to be influenced by coping strategies and empowerment, which would influence control beliefs The CORAL model does not take interpersonal or organizational factors into account, instead focusing exclusively on personal needs and values.

In a similar vein, the theoretical model developed by Chaudoir and Fisher [36] posited that the disclosure decision is influenced by antecedent goals, and that these generally can be categorized as approach or avoidance goals. The individual’s orientation towards approach or avoidance then shapes the disclosure event itself and its ultimate consequences. The literature discussed here has added significantly to our understanding of disclosure, but it lacks a full development of the disclosure process that is specific to the context of mental disorder and work, one that goes beyond reasons to disclose and reasons to not disclose to a full consideration of the context (interpersonal and organizational) for disclosure. Understanding the disclosure decision-making process can assist employers to develop effective programs, policies, or interventions that seek to reduce stigma in the workplace, thereby enabling employees who wish to disclose to do so without fear of negative consequences.

Methods

The study employed qualitative research in the grounded theory [40, 41] tradition to address the research question. The study site was a post-secondary educational institution in Ontario, Canada. Inclusion criteria included: (1) current employee of the organization, (2) diagnosed with a mental disorder recognized under the DSM-IV-TR, (3) by a qualified health professional. Participants were recruited through a two-pronged strategy. First, the staff of Employee Health Services (EHS), a division of human resources, provided information about the study to all eligible recipients of EHS services during regular meetings. Second, posters, e-mails, and newsletter articles targeted the general employee population. Interested employees were asked to contact the researcher.

The final sample consisted of 13 participants, at which point theoretical saturation was reached [40, 41]. The unit of analysis was the individual disclosure decision. Decisions about disclosure are not made once and then applied to all contexts, but rather are complex decisions made as part of an information management strategy that may vary based on a number of factors [42, 43]. As such, participants were able to make a decision to disclose in one context and to not disclose in another. Therefore, participants were asked to discuss various disclosure decisions made in the context of work, and these incidents were analyzed individually.

Data were collected through in-depth, one-on-one interviews, lasting an average of 60 min. An interview guide was developed based on the literature review conducted for the study, and the guide was reviewed by the occupational health nurse and occupational medical consultant at the study site. The interview guide consisted of seven questions with several sub-questions for clarification and/or probing for a more detailed response.

Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim; transcripts were imported into the NVivo 8 qualitative data analysis software package for storage and analysis. The researcher conducted open coding on each transcript [40]. Open coding involves a line-by-line review of the transcript with the generation of codes to describe the actions and processes in the data [44]. As open coding continued, a core variable began to emerge from the data. The core variable was identified by its centrality to the disclosure decision-making process described by the participants. Once open coding was completed and the core variable was identified, the researcher progressed to selective coding [40]. Through the selective coding process, the researcher identified the codes and concepts that were most significant and/or frequently mentioned by participants as related to the core variable. These codes were then further analyzed to determine the properties and conditions under which they helped to explain the phenomenon under study. Analysis was aided by extensive memo writing about each concept.

During the theoretical coding phase [40], the researcher hypothesized about the relationships between the core variable and the selective codes surrounding it. Theoretical coding led to the development of the decision-making model. The researcher then returned to participants to obtain their reactions to the decision-making model as a method of member checking. All participants were contacted to request a member checking interview; nine chose to participate. Member checking interviews lasted an average of 30 min. Interviews were audio recorded, and data gathered were used to refine the model to its final state. This project was approved by the Walden University Institutional Review Board and the study site’s Research Ethics Board. The participants all signed informed consent forms and agreed that interviews could be recorded.

Results

The final sample consisted of ten women and three men, ranging in age from 21 to 55. In Canada, organizations may have one or more unions that represent their workforce and in such cases, the organization enters into a collective agreement with the union regarding labour practices and how the workforce will be governed. Management employees, even within unionized environments, are usually not members of the union. Twelve of the participants held staff positions; six staff held non-unionized management roles, four held permanent unionized roles (e.g., administrative assistant, research assistant), and two were graduate students with unionized temporary teaching assistant roles. One faculty member was represented in the sample. Ten of the participants had been employed with the institution for less than 10 years and three participants had been employed for more than 10 years.

In terms of diagnoses, two participants had disorders classified as those normally identified in childhood or adolescence (Asperger’s syndrome, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder). One participant had a substance-related disorder (alcohol use disorder). Three participants had anxiety disorders (obsessive–compulsive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia). Nine participants had mood disorders (major depressive disorder, bipolar II disorder). Two participants had co-morbid disorders from different categories. Time since diagnosis varied as well. Two participants had been diagnosed less than a year before the study, while many had been diagnosed 10 years ago or more. Two participants had been diagnosed more than 20 years earlier. Diagnosis was often made while the participant was in his or her early to mid-20s, with two participants being diagnosed earlier in childhood and two being diagnosed around age 50.

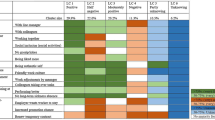

The findings of the study indicated that participants embraced a default position of nondisclosure at work that was due to fear of being stigmatized. This is not to say that participants had not disclosed at work, because most (11 of 13) had disclosed to someone; however, participants discussed needing a rational reason to move away from the default position of nondisclosure. The decision-making process itself can be described as a risk–benefit analysis, during which employees weigh risks and benefits within the existing context as they assess it. The theory (displayed graphically in Fig. 1) allows for a visual representation of the sequence of “events” in the decision-making process as described by participants. In the model, the default position of nondisclosure is reinforced by fear of stigmatization, and the desire to maintain boundaries and confidentiality. In the following section, we discuss the meaning of these factors. We then proceed to walk through the rest of the model.

Fearing Stigmatization

When asked about the basic problem with disclosure at work, the problems identified by participants were related to the stigma of having a mental disorder. One participant, Marcus,Footnote 1 described disclosure as “putting yourself under that microscope”, something that is quite difficult to do “unless you’re quite strong or confident.” Participants discussed: (1) the differences between disclosing a mental versus a physical health issue, (2) the stereotypes associated with mental disorders, and (3) being seen and/or treated differently once people knew.

Difference Between Disclosing a Physical and a Mental Health Issue

Participants spoke about the difference between disclosing a physical and a mental health issue. They felt that mental health issues were more likely to result in being negatively labeled than physical health issues; that they are subject to more-and what participants felt were more severe-stereotypes; and that the desire to help people with disabilities does not seem to extend to people with mental disorders. Participants acknowledged a silence in the workplace surrounding mental disorders, and that their disorders were often not perceived as serious in comparison to some physical health issues:

[I]f I come in with a broken leg everyone gets it…You come in depressed nobody gets it. I shouldn’t say nobody, but a lot of people don’t get it, right? So the biggest barrier to work, to disclosure at work, it’s probably the fact that it would be received so much differently than any other health illness. One of our colleagues had breast cancer here…Like unbelievable support for that. To follow that up with I need some time off because I’m depressed, it doesn’t carry the same kind of weight. Breast cancer is like oh my God. Depression’s like oh give her a pill. (Sandra)

Stereotyping

Participants spoke about three primary stereotypes that they felt were applied to employees diagnosed with mental disorders. All of the participants expressed the fear that they would be perceived as incompetent to do their jobs:

[P]eople in my office have no idea. They think I’m one of the most balanced people they know. Like people are coming to me at the office like well what do I do about this? How do I say that? What do I do with this? I think…a lot of that would be gone if people found out and that’s just because of lack of knowledge. But I don’t want to be the person they’re learning on…I’ve worked really hard to be where I am and I don’t want to lose that by just, you know…one disclosure. (Sarah)

A second stereotype identified by participants was the perception of being responsible or at fault for having the disorder. Participants spoke about being told that they should just “pull up their socks” and “get over it”. Participants spoke about applying this stereotype to themselves:

I really feel like some…somehow…if I did something differently or…I feel like maybe it’s my fault that I have anxiety disorders. Like I don’t know, I can’t even explain it, I don’t think, any better than that; I just feel like…it’s either my fault or people would think it’s my fault. And I probably think it’s kind of my fault, honestly. That if I just thought properly or managed my life properly I wouldn’t have these misfiring neurons. And when I say it that way it sounds ridiculous, because obviously I can’t control that, but…yeah, I guess I just, I feel like it’s somehow my fault and it’s like admitting I’ve done something wrong. (Amanda)

Self-stigmatization in this area was linked to a reluctance to seek treatment, and several participants spoke about delaying help-seeking because of the internalized message from others that they should “just get over it”.

About half of participants expressed concern that they would be perceived as faking or trying to manipulate the system if they disclosed their mental disorder at work. In fact, this is a stereotype that many workers face when they take a leave of absence from work due to disability, whether related to a physical or mental health issue [10, 11]. Some, like Andrea, Beth, and Marcus, were concerned that it would be viewed as an excuse for lack of performance. David talked about the fact that mental disorders are particularly subject to the stereotype of malingering because they are invisible.

Being Treated Differently

Many of the participants talked about not disclosing because they did not want any special treatment at work. Participants expressed concerns that their disclosure would be held against them at some point in the future, that others would judge them or see them differently. Participants were highly cognizant of the fact that once they disclosed, they could not take back what was shared. It was particularly important that those they told would maintain their confidentiality. Many expressed concern about being the subject of gossip within the workplace:

But it would be that other people would talk about that and I wouldn’t want that because I feel like some things are so like personal that you know you don’t, you don’t really want other people that you work with and people who…I guess people who you work with that might think that it would affect your performance or something and might view you kind of in a different way. (Beth)

The participants spoke about hearing derogatory statements about people with mental disorders made by their coworkers. Getting to know people is a critical condition for disclosure at work and generally participants assessed others’ attitudes towards mental disorders before disclosing. Lisa explained it as:

[M]ost of the time I wouldn’t tell…I don’t tell strangers. And by the time you tell somebody you’ve generally heard them make comments one way or another whether or not, you know, they’re all fakers sort of thing.

Moreover, one negative individual in a work setting often resulted in a blanket policy of nondisclosure that was applied to everyone in that setting. For example, Sarah shared the following story:

One person I work with, her son has just recently gone on antidepressants and as far as she’s concerned–he’s 30 years old, by the way–and as far as she’s concerned that’s totally the wrong thing to do, antidepressants don’t do anything for anybody and you have…She knows everything. [laugh] It’s just an excuse, it’s a crutch, it’s lazy because you don’t want to pull your socks up…And I’m sitting there going thank God I didn’t open my mouth. Because that’s not what I’ve worked so hard to have people view me as.

Maintaining Boundaries

Participants protected themselves from stigmatization through a default position of nondisclosure. Nondisclosure was a preferred strategy because it maintained boundaries between work and home lives. Many participants discussed their health status as private, and indicated that they liked to maintain boundaries between these two aspects of their life. Health status, then, was something that they were unlikely to share as something that belonged in the personal sphere. David talked about the power of labeling in relation to his private life:

[I]f someone knows such a…like, as much as I don’t like the, the terminology, Asperger’s in my case can be a, it’s not a way of life but it gives significant insight into my character, and…in a way I see it as kind of an intimate detail of my life, so that’s why on some level I also like to keep it private is because of that intimacy.

Individuals in management positions talked about being friendly but not friends with people at work. For example, Sandra commented:

I think that’s part of my own personal division between home and work, and I think I’ve always, I’ve always been like that. I’ve always got along with my colleagues very well, and rarely socialize with them…except in an official capacity. And I think I’m most comfortable there. I think in my mind I need to separate work.

Maintaining Confidentiality

The default position of nondisclosure also served to protect confidentiality. Participants were reluctant to share information about their health status due to the concern that the confidential nature of that disclosure would not be respected. Sarah shared a scenario in which she would have disclosed to help the other person if she thought her confidentiality would be maintained:

I see she’s one of those people you’ll tell her something and you tell her not to repeat it and she goes and repeats it within 10 s. That’s really been the only reason why I haven’t [disclosed]. So for me I feel the risk is too big. I think her knowing though on a personal level would probably be really good for her but if she wouldn’t blab it to everybody else.

Triggering Incident

Participants remained in the default position until some kind of triggering incident led them to believe there may be a reason to disclose. The triggering incident could be any number of things, from struggling with work to a conversation with someone in which that individual shared a personal problem. It was simply something that occurred in the work life of the employee that suggested the default position of nondisclosure should be reassessed in that particular circumstance. The triggering incident launched the decision-making process, but information used in the process (e.g., characteristics of the other person) was gathered over a longer period of time (e.g., since meeting that individual). For example, Vivian started to consider disclosing when she realized her mood disorder was affecting her colleagues:

I got to a point where I needed to [tell my coworkers] because I came back from being off and their first reaction was are you ok? And I said yes. And they said is anything … what was wrong? And I said I just was ill, and I didn’t go into it…But just, as time went on, I knew I had to tell them because I could see my mood disorder was affecting them…I was having them come to me saying have I upset you Vivian? Have I … like have I done something to make you mad? Are you angry with me? And then I would have to say no, no, I’m not, I’m just … I’m not in a good mood. Like I would just have to say that because I had no other way to say it and finally I thought I just … I have to tell them because I need them to know it’s not their fault and I’m not mad at them, I just have this problem.

Kelly disclosed to her new supervisor when they had a conversation about her supervisor’s son:

I had known her no time at all, but she was going through a very difficult time with her son being hospitalized for depression. She was just at the end of her rope and I thought my experience might be helpful to her, so I told her…I didn’t really know her and she didn’t know me. I was worried that she would think less of me, think I couldn’t do the job I was in. But I took the risk because I honestly thought my perspective might help her; she was so clearly in great distress. And it did help, she was grateful to know that someone could go through what her son was going through and turn out ok.

Given the role of the triggering incident in the decision-making process, this meant that in most cases participants made disclosure decisions spontaneously in the moment; however, this did not mean a circumventing of the rest of the decision-making process (see further discussion under Weighing Risks and Benefits). Once the triggering incident occurred, the individual moved into an information gathering period, including both reasons to disclose and conditions for disclosure. It is important to note that while the information is gathered for consideration in the decision-making process at this time, the actual process of learning about all the relevant conditions may take place over a much longer period.

Reasons to Disclose

Participants discussed needing a “good” reason to disclose if they were to move away from the default position of nondisclosure:

So if by disclosing…if I’m just disclosing for the sake of disclosing and it’s not going to do anything positive, why would I disclose? I don’t see why I would make things harder for myself or others, for just for the sake of disclosing. If it would help things, great; if it wouldn’t, then why am I doing it? So, if…I, I usually don’t disclose if it’s not going to change anything. (David)

Reasons to disclose were categorized as: (1) interpersonal, (2) work-related, or (3) personal reasons.

Interpersonal Reasons

Interpersonal reasons for disclosure were usually other-focused. Participants most often disclosed to help others. Their experience was frequently shared as a method of expressing understanding of a difficult time the other was going through or to offer support to those struggling with mental disorders:

With disclosing to the person who was reporting to me for a period of time, it was really about letting her know…because she didn’t feel supported by the director, right?, who couldn’t understand what she was going through. It was really about letting her know that she wasn’t by herself and the fact that she was seeking help was such a significant step that she should be very proud of herself. It shows…I mean that’s a kind of thing that a manager would want to see, that you’re actually taking steps as opposed to letting it just happen. So, so it was for that purpose that I disclosed it to her, purposely…with a lot of thought. (Vanessa)

Approximately half of the participants talked about disclosing at work because their disorder was negatively affecting others around them. For these participants, it was very important that their coworkers knew that they were not at fault:

I think the advantages of disclosing…with the people that you work with is that they learn not to assume that if you’re kind of miserable on a given day that it really has anything to do with them, right? They don’t have to make that assumption that oh man, like what did I do or, or, you know, get mad at me saying you know what’s your problem about this. Because they can say to themselves, now they may not say to themselves, they may not think about it either, but, you know, at least, you know, you’ve let them off the hook or given them some information to let them know that how you are at a particular time isn’t a result of your relationship with them. (Vanessa)

Most of the participants talked about disclosing to build closer relationships with others. They felt that disclosure was necessary for further development of those relationships. Such conversations often occurred in the context of reciprocal sharing, with goals of building the relationship and offering understanding as a method of helping. For example, Amanda said:

I guess part of my beliefs is that in order to have a genuine relationship with people, there’s a certain amount of openness that needs to be there. So I think that certainly affected when I mentioned about [coworker], I felt like I wanted to have a genuine, close relationship with her.

Participants talked about disclosing to correct misconceptions or challenge stigmatizing attitudes of others. In some cases, participants disclosed to challenge a specific individual’s belief structure, while at other times it was meant to educate more than one person. Lisa disclosed when coworkers talked negatively about another colleague who took a leave of absence for depression. Thus, the criticism was the trigger and the desire to dispel stigma became the reason to disclose:

The people that have a misunderstanding about it and often they’ll make a generalization–well depressed people are this. And I’ll say well I have it, can you tell, you know? Do you think that my job has been affected?

Participants did not always choose to disclose under those circumstances, however. Balancing fear of being stigmatized with a desire to be open was a challenge for many. Vivian talked about her struggle with disclosure decisions:

[T]here’s days where I definitely start feeling like I don’t even care who knows. I don’t care if people know. Maybe they should know. Maybe it’s better if they know. Maybe I’ll be the person that helps that person realize, look you know someone with a mental illness and you talk to them and you go for coffee with them and you’re friends with them and you don’t even…you didn’t even know they had one…Like maybe I could be the person that changes their viewpoint. But then I think do I want to take that on myself and I might be the one that ends up suffering if I do that.

Work-Related Reasons

Sometimes participants were motivated to disclose at work for reasons related to the work itself or the work environment. Two primary motivators for disclosure were when the disorder or its symptoms were affecting work, or when disclosure would help the participant overcome a work challenge. Often, a primary consideration for participants in deciding whether to disclose was whether the disorder or its symptoms was affecting their ability to do their job. If the disorder was affecting work they were more likely to disclose; if it was not affecting work, most would not mention it.

Participants spoke about gaining increased understanding from others at work as a benefit which could result in positive job outcomes like instrumental help in carrying out work tasks. Peers could provide emotional support, but they could also provide assistance with tasks. For example, Vivian talked about a peer who offered to cover her desk for her any time she just needed to get away. Supervisors could rearrange job tasks or extend deadlines in a way that provided relief for the employee. David spoke about an understanding of his abilities as potentially allowing his employers to see where he would best fit within the organization. Several of the participants talked about behaviors being better understood within the context of a diagnosis; where some behaviors would be considered less than desirable in the workplace, within the context of the disorder they could be better explained. David shared:

If I had a breakdown or, I’m trying to get the clinical term I think is behaviour…if I had a meltdown, which has happened before but not often and usually it’s when everything has just piled on and on and on and on, and it’s just too much and I explode…at least they would have some sort of, maybe not warning but at least an explanation. And I know that at some times I can be very, I can be very blunt and I can be very tactless at times or say things that are interpreted in ways that I didn’t foresee.

Personal Reasons

Participants also disclosed at work for personal reasons, including eliminating the need to keep a secret. Participants found keeping a secret to be burdensome, and in that way disclosure could be liberating. Andrea and Beth talked about the benefit to others of disclosing in terms of reducing stigma. Participants spoke about their desire to be their authentic selves with others, and this included disclosure:

For me is that I’ll be more relaxed to be myself. Because when I was depressed I was holding my…tears every minute…and it was so difficult to act normal and it took a toll on me. It was horrible….Like if you think of the benefits for me that pressure that is on me to hide it will be lifted…That will help a lot. (Miriam)

Assessing Conditions for Disclosure

A process of assessing conditions for disclosure also occurs, in which the individual looks at interpersonal, work, and personal conditions. Information gathering is a complex process where any perceived change in risks, benefits, or conditions may influence the decision-making process. Reasons to Disclose and Assessing Conditions are portrayed as overlapping constructs within the larger circle in the model to capture the dynamic, interdependent, iterative nature of the concepts. At any moment, conditions or reasons may change.

Interpersonal Conditions

Participants placed the greatest emphasis on assessing conditions related to the characteristics of the person to whom they were considering disclosing. Interpersonal conditions were assessed through getting to know people, which usually entailed a fair amount of time, interaction, and observation. Amanda stated:

I think I…tend to assess whether or not they’re judgmental people based on like our conversations and maybe their observations about situations or other people.

Vivian pointed out that taking the time to get to know someone means they also get to know you, which can be a great benefit in disclosing:

But it’s usually once I’ve gotten to know people and then I’ve built a relationship with them and I trust them…Because they don’t know me when I’m starting a new job and so I feel like…once you get to know me you know my personality now, so now if I tell you I have bipolar disorder well I’m still the same person you knew for the past year, so you know me already. And there’s a background…you know, a familiarity with me and so I think it’s more accepting. I think that if I just come in off the street and you don’t know me and I say I have bipolar disorder, I think people look at me differently.

The individual assessed several characteristics of the other, including whether the other was open, likely to be understanding, likely to be supportive, and could be trusted. Participants spoke about openness of an individual being critical to the decision to disclose. Openness seemed to be defined as the opposite of judgmental:

So I would also probably encourage them to think about who they’re talking to…think about their openness and whether or not they tend to be judgmental people, if they’ve ever made comments about family members or anybody that they know that has the same kinds of issues, what their responses to that have been. (Amanda)

Participants spoke about understanding people as people who “get it”. Lack of understanding was characterized by attitudes of “just get over it”, “pull up your socks”, “what do you have to be sad about?”, “that’s just an excuse”, and other such descriptions. Individuals who made these comments were thought to be ignorant of the true nature of mental disorders; thus, participants strongly linked education, knowledge, or experience with mental disorders to understanding.

All of the participants stressed the importance of trusting the person to whom they wished to disclose. Trusting was referred to as faith that the person would maintain their confidentiality. Trusting was also about knowing that the information would not be used against participants. In this sense, trust was particularly important in power relationships such as disclosing to supervisors. Lisa asserted that there had to be a greater level of trust in a relationship when disclosing to a supervisor versus a peer:

So in fear of that…yeah, I think there is that, there is that more of a fear when you tell a supervisor. So there has to be a lot more trust, I think than when you tell a colleague. I think I have to trust them a lot more that they aren’t going to try and use it against me; that they aren’t keeping it in the back of their mind. And that’s the hard thing is you don’t know if they are. You have no idea if in the back of their mind, you know, they may not write it down but when you’re up for a raise and they look at you and the next person and go well they’re pretty much the same but, you know, she does have that instability.

Work-Related Conditions

The culture of the workplace is also important to the disclosure decision, and participants assessed these conditions as part of the decision-making process. In discussing the work environment and its contribution to disclosure decision-making, participants considered norms of personal disclosure in the workplace and how the department or unit had handled past sensitive situations. Lisa described norms for personal disclosure as follows:

The environment, people around whether or not there’s a welcoming environment for disclosure. You know, do other people feel comfortable talking about themselves? Or am I the only person in the room that’s told my life story and everybody else going, we tell each other nothing? Now if other people are disclosing their life stories and you know other things you feel more comfortable with it. But if other people no one discloses, and I know a lot of work environments where people are like that, where you know you’re here to work, you’re not here to socialize, it’s none of your freaking business what my family’s going through or whatever, and move on. So you have to take that into consideration.

Participants discussed observing how other sensitive situations have been handled in their departments in the past, and using their observations to inform their disclosure decisions. Sensitive issues were not limited to mental health, but rather to how the department treated its employees in general. For example, Andrea spoke about not trusting the human resources department because she, personally, had seen information that was supposed to be kept confidential. Beth talked about the negative reactions of her coworkers to a new employee who quickly took a maternity leave, and Miriam indicated that she would not tell a person who behaved harshly towards employees who had to care for sick children.

Perceived job security is critical to the decision to disclose. Many of the participants talked about fear of losing their jobs when asked about the problem with disclosure at work. The nature of the relationship was thus important to decision-making, as participants acknowledged power differentials in disclosing to supervisors. Amanda disclosed to peers to build the relationship, but if she disclosed to supervisors it tended to be for work-related reasons. Kelly only told her former supervisor once she was no longer her supervisor, and the relationship shifted more to the personal. Lisa stated that there had to be a lot more trust before telling a supervisor compared to telling a peer.

Participants who were aware of their rights related to disabilities under Canadian legislation tended to feel they had greater job security and could not be discriminated against based on the mental disorder. Amanda disclosed without fear of reprisals when a reason presented itself:

Well, I think that knowing the environment we’re in and knowing that I have the protection of the human rights code and that alcoholism is a disability has…made the risks seem really small to me. Because I know that there’s nothing that can be legally done to discriminate against me on that basis; it’s really taken away that idea of that risk; it just doesn’t even bother me, that kind of idea…Yeah, I just…it doesn’t frighten me; I feel like I would be able to address it if something negative was to happen in that way.

Awareness of legal rights did not always result in perceptions of greater job security, however. Kelly stated:

I worry that people won’t think I can do my job effectively, that I’m weak. Even though I know that mental disorders are protected as a disability under Canadian employment legislation, I still worry that the knowledge that I’ve struggled with depression could blow my chances at advancement. People can’t be blatant about that, but I know how easy it is to make an excuse that is legal while hiding the real reason for not hiring someone.

Personal Conditions

Participants assessed more personal conditions in making disclosure decisions, including status of the disorder, and outcomes of prior disclosure decisions. Status of the disorder was related to many different factors. Although participants expressed relief to be diagnosed, there was often a period of denial through which they came to terms with the diagnosis. Some participants expressed regret about waiting so long to seek treatment. As participants developed a level of comfort with and understanding of their disorder, they were more likely to disclose.

Phase of illness was also important to the disclosure decision, and was related to salience of the disorder in the participant’s life. Some participants were more likely to disclose when things were going well (i.e., relief of symptoms, performing well at work) as they felt better able to handle the disclosure and its consequences. Other participants were more likely to disclose when things were not going well (i.e., experiencing symptoms, performing poorly at work) as a help-seeking measure. Beth and Sarah talked about level of life interruption, indicating that someone may wish to disclose if their life is highly interrupted by the disorder and not disclose if it is not as disruptive to day-to-day life.

Status of the disorder was also relevant in terms of diagnosis. Just as participants felt that disclosing a mental health disorder was less socially acceptable than disclosing a physical health concern, they felt that certain mental disorders were less socially acceptable than others. Amanda, for example, disclosed the alcohol use disorder far more often than she disclosed the OCD diagnosis, feeling that OCD was more likely to be viewed as a weakness. In a similar manner, Lisa was more likely to disclose ADHD at work than depression.

Participants considered their previous experiences, both positive and negative, in making decisions about disclosure. Past experiences with stigma led to a reduced chance of disclosure in future situations. Sarah spoke about being passed over for a promotion based on her disorder:

That person found out because I was…during the time I was extremely depressed, she happened to be around and I guess my boss had said something to her and she inferred, she inferred correctly…but she had inferred this and just…she never said anything to anybody else but when it came down to applying for a job in the residence she was working at she thought that…and I didn’t get the job and I thought, and a lot of people thought I was a shoe-in for it. It was you didn’t get the job because I think the stress would be too much for you considering that you’re depressed…And I go, oh really? Ok. I don’t agree. [laugh] I don’t think that’s right.

While only three participants shared personal experiences with discrimination resulting from a disclosure at work, all of the participants feared such stigmatization.

Weighing Risks and Benefits

While assessing conditions may take place over a period of time, weighing risks and benefits typically occurred very quickly as the individual discovered a reason to disclose. Most disclosures occurred spontaneously. Even when disclosure was deliberated over a long period of time, weighing risks and benefits still occurred in the moments before disclosure, and any change in conditions or the importance placed on factors could cause a last-minute change in the decision. Through an iterative process of weighing the risks and benefits, the final disclosure decision is made. Although disclosure was spontaneous for almost all participants in the study, they discussed a quick consideration process in the moment:

Generally when I have told people it’s been like comes up in a conversation and in the back of my head I think am I going to tell it?, am I not? It’s not that I sat down and said ok it’s time I have this talk with you, you know; I want to disclose something….It just…it’s usually a quick thing, quick rush through my head saying do I, don’t I? And I tell myself over and over again, it’s not a big deal. (Lisa)

David was the exception in the sample. He discussed sitting down with his significant other and making a pros and cons list to help him decide whether to disclose or not in a particular situation. However, Lisa pointed out that all disclosure decisions are to some extent spontaneous:

It goes through your head very fast…Because, thinking about it, even instances where you think about it for a time, going should I?, shouldn’t I?, should I?, shouldn’t I?, but when the…time comes, it’s kind of a spontaneous, is this it? Yes or no? You know, that sort of thing, so. Even when you think about it for a long time, generally speaking there is that quick moment: is this the right time? Because even if you plan it, you may find, you know, you’ve booked a meeting to speak to your boss or whatever, but if, when you get to that moment, you go wow, this is just not a good day to deal with it. So…no matter how long you’ve had, there’s still that quick, snap, quickly run through your head… It kind of makes a weird conversation, when you’ll sit there and pause for a second, you’re kind of like Ummm…And then people go oh crap, what is she going to say? Because you do that [laugh], as you’re running through your head, am I going to say this?, am I not going to say this?, you know. But it’s very spontaneous, no matter how much you plan for it, there is that spontaneity about it.

After weighing risks and benefits, the disclosure decision is made, whether it’s to disclose or not disclose in that particular context. The individual then returns to the default position until the next triggering incident occurs. One disclosure decision may trigger the need to make one or more subsequent disclosure decisions, and these decisions may not be independent of one another. Thus, it is possible that the loop back may route to another triggering incident instead of automatically to the default position.

Discussion

Fear of stigmatization has been linked to nondisclosure of discreditable attributes in a variety of settings. In the workplace, fear of stigmatization may lead employees to choose not to disclose a mental disorder, thereby limiting help-seeking through workplace accommodation. Research suggests that a variety of factors are considered in making decisions related to disclosure of concealable stigmatizing attributes, yet limited literature explores the process of disclosure decision-making in the context of mental disorder and work. The purpose of this study was to discover the decision-making process of individuals diagnosed with a mental disorder regarding disclosure of the mental disorder at work.

Factors Influencing the Default Position of Nondisclosure

The findings of this study related to the factors influencing disclosure decisions both support and extend the literature on this topic. Fear of stigmatization led to a default position of nondisclosure in the workplace. There were both similarities and differences in the types of negative consequences feared by the participants in this study compared to what has been documented in the literature. Participants feared being the subject of gossip [35, 45], social rejection in the form of being judged and being seen differently [14, 35, 46], betrayed confidence [32], and loss of job or opportunities for advancement [34, 35, 46, 47]. Fear of violence and harassment have been discussed in the literature [14, 46, 47], but these concerns were not mentioned in this study. Instead, participants talked about fear of stereotypes such as incompetence to perform their jobs and being held responsible for the disorder. They were also concerned about being perceived as faking or trying to manipulate the system. Such stereotypes are common for mental disorders [4, 48] and disability more generally [19, 20].

Critical Reasons to Disclose

Interpersonal Factors

Interpersonal factors were found to be most important in the disclosure decision-making process. The literature reviewed suggested that the presence of similar others was significant [26]. There does not tend to be a community of individuals diagnosed with mental disorders within organizations; thus, employees are unlikely to know about similar others. However, the findings of this study do support that individuals are more likely to disclose to those who have disclosed something personal in nature to them. The concept of reciprocal sharing was often cited as a reason for disclosure.

Supportive work relationships are critical to the disclosure decision-making process [31, 32, 34, 47]. This finding was confirmed by the present study. Characteristics of the other person were identified as most important. Characteristics were assessed through getting to know someone, and included assessment of openness, understanding, supportiveness, and trustworthiness. The nature and the quality of the relationship were important. The literature documents the closeness of the relationship [32, 42, 49], but the present study found that a higher level of trust was required for disclosure to a supervisor due to the power relationship. Participants spoke about the fear that the information about the mental disorder would be held against them at some point in the future by the supervisor, due to the supervisor’s influence over work opportunities such as promotions. In fact, this is contrary to some research that has found that employees are more likely to disclose to a supervisor than to coworkers [50]. Research by Granger et al. [51] suggested that individuals tended to favour disclosure to supervisors over coworkers due to the greater risk of social rejection and ostracism from coworkers. It may be that the reasons for disclosing to supervisors and coworkers (e.g., to gain support versus social reasons such as building relationships) may influence the choice of recipient and the perceived risks and benefits.

Critical Conditions Influencing Disclosure

Environmental (Work-Related) Factors

Research has suggested that company policies, diversity climate, and nondiscrimination policies that are visibly enforced are significant to disclosure decision-making [29, 31, 52]. This study found that work unit climate was more important to disclosure decision-making than organizational level factors. Participants assessed norms of personal disclosure in the work unit and how sensitive situations had been handled in the past. They were more likely to disclose if other employees discussed personal issues and less likely to disclose if they perceived that sensitive situations had been handled poorly. While work unit policies stem from overall company policy, in large organizations culture can vary substantially from department to department, including enforcement of policies surrounding negative employee behaviors [53]. Organizational supportiveness needs to be a core value that is lived out in the day-to-day culture of the organization [29].

Perceived job security is not often explicitly mentioned in the literature as a factor in decision-making, but it was a prominent finding in the present study. Participants were concerned about losing their job or losing opportunities for advancement if they disclosed. Perceived job security seemed to be linked to awareness of legal protections against discrimination [29, 34]. Amanda, for example, had extensive knowledge of her legal rights by virtue of her profession, and felt very safe in disclosing because of it. Other participants, however, did not feel fully protected by the legislation due to the difficulty of proving allegations of discrimination based on disability. Such concerns would appear to be legitimate given the success rate of discrimination claims under human rights legislation [54].

Personal Factors

According to the literature, personal factors that influence the disclosure decision include personal motives, the desire for privacy, centrality of the stigma to identity, and degree of self-acceptance/self-stigma. Motives were central to the decision-making process; in fact, participants needed a reason to disclose before they began the decision-making process. Findings of the study were congruent with previous research, in that participants disclosed to build relationships, to change other’s attitudes, to request accommodation and/or cope with work challenges [29]. This study extends the research on motives for disclosing into the altruistic realm, in that the most cited reason for disclosure by participants was to help others. Participants also disclosed because the disorder or its symptoms were affecting others at work, to gain increased understanding from colleagues, and to free themselves from the burden of keeping a secret.

The literature suggests that degree of self-acceptance/self-stigma and centrality of the stigma to personal identity as factors that are considered when making disclosure decisions [31, 42, 47, 55]. This study found that the status of the disorder was one of the conditions assessed. Status of the disorder encompassed level of comfort with the disorder, which required the participant to accept and learn about the condition. Comfort with the diagnosis was considered necessary to disclosure by participants. A couple of participants touched briefly on centrality of the stigma to identity when they talked about degree of life interruption. With mental disorders, the status of the disorder can change as individuals go through highly symptomatic and non-symptomatic phases. Individual differences and situational context led the effect of status of the disorder on disclosure decisions to be highly variable. For example, some participants were more likely to disclose during high-symptom periods as they struggled to cope, while others were less likely to disclose in that scenario.

Outcomes of prior disclosure experiences were fundamental to the decision, a finding which supports the literature [32, 34, 43]. Three participants in the study shared negative experiences following disclosure, from being treated differently, to being passed over for promotion, to non-renewal of a contract. However, all participants also shared positive experiences, and reflected on the influence of past disclosure decisions in making future decisions. As discussed by Herman [43] and Sowell et al. [32], negative past experiences led to greater caution in disclosing. Even for those who had not had a negative experience, fear of negative reactions or outcomes contributed to the default position of nondisclosure at work.

Recommendations for Action

The findings of this study are useful for human resources and occupational health professionals, as well as supervisors/managers. It is important to note that a normative stance should not be placed on disclosure; rather, the organization should strive to create an environment in which employees feel safe to disclose should they wish to do so. Study findings confirmed that a default position of nondisclosure was adopted because of fear of stigmatization. Stigma involves cognitive, affective, and behavioral responses from others towards an individual diagnosed with a mental disorder. Reduction of stigma is challenging because it is often a result of deep-level attitudes [27]. The findings of this study suggest that training for managers and staff would be helpful in reducing stigma related to mental disorders in the workplace. While this may seem to be an obvious conclusion, research suggests that greater education related to mental disorders in the workplace is still needed. For example, Lemieux, Durand, and Hong [56] found that supervisors had an important role to play in the successful return to work of employees diagnosed with a mental disorder, but that lack of knowledge and tools related to mental disorders were a barrier to successful return to work. A recent review of the literature highlighted the need for training of management and supervisory staff in auditing for mental health risks, early detection and intervention with employees, and creating organizational conditions that promote a mentally healthy workforce [57]. A study of employer attitudes towards hiring and accommodation of employees with mental health disabilities in Canada [58] found that employers still hold a variety of stigmatizing attitudes about mental illness. The authors called for “awareness raising, education, and fear reduction for employers and coworkers” (p. 337). The findings of our study and this recent research support the need for continued efforts in this area.

Many media campaigns and educational interventions have focused on dispelling myths about mental illness as a way to reduce stigma, but research suggests that increased knowledge about mental illness does not necessarily translate to changes in negative attitudes or stigmatizing or discriminating responses [59]. Although these campaigns were not specifically focused on the workplace, this research suggests that we need to go beyond simple education to provide concrete tools and strategies that managers can use to address challenges related to working with employees diagnosed with a mental disorder. The findings of our study suggest some important content for training, including accurate information that challenges stereotypes related to job competence/performance, attribution of responsibility for mental illness, and faking or trying to manipulate the system. It should make explicit the differences in reactions to disclosure of a mental versus a physical health issue, with the goal of eliminating the stigmatizing reaction to mental disorders. It should highlight the effect of derogatory statements (for example, greater awareness of the colloquial use of the term crazy), and behavioural responses that indicate judgment and a changed view of the individual who has disclosed. Finally, it should indicate the hurtful nature of gossip and the importance of maintaining confidentiality. Additional training for managers related to the power imbalance inherent to their supervisory role should be developed. It should include education on how to create safe spaces for disclosure (e.g., how to demonstrate openness, understanding, supportiveness, and trustworthiness), and training on appropriate responses to behavioural changes. The training should also include education on appropriate interventions if it is suspected that any employee is being bullied or harassed at work, including unprofessional behaviour among coworkers. The training should include the provision of practical tools that help managers in identifying employees who may be in difficulty and assisting those employees during times of absenteeism, presenteeism, slipping performance, leaves of absence, and return to work.

Study Limitations

The study was conducted with employees from one post-secondary educational institution in Ontario, Canada. As such, findings of the study may be influenced by specific organizational culture, context, and factors. However, the study site is a large employer with a diverse workforce, which should aid in transferability of the findings. Given that the study was conducted in a large organization, we do not know how well the findings may transfer to employees in small organizations. While organizational context in small compared to large organizations is likely different, the factors identified in this study (organizational culture, policies and practices, perceived job security) are likely to still be of importance in disclosure decisions. Future research might explore the impact of organizational size on disclosure decision-making.

Although participants were asked to confirm that they had received a diagnosis from a qualified health professional before being admitted to the study, verification from that health professional was not required. Thus, it is possible, although unlikely giving the screening process, that participants provided a self-diagnosis. Furthermore, participants in this study had diagnoses that are generally considered to be common mental disorders (e.g., anxiety and mood disorders) as opposed to more severe mental disorders (e.g., schizophrenia). This is not surprising given that the most frequently identified workplace mental health disabilities include dysthymia, major depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, panic disorder, and social phobia [60], and since individuals with severe mental disorders are significantly less likely to be employed [61, 62]. However, the disclosure decision-making process may be different for individuals with more severe mental disorders due to more pressing needs for accommodation in the workplace [8].

Conclusion

The key finding of this study was the importance of a triggering incident suggesting there might be a “good” reason to disclose to launching the decision-making process related to disclosure of a mental disorder at work. Without a good reason, employees remain in the default position of nondisclosure. However, having a good reason is not enough. The benefits to disclosure must outweigh the risks, as assessed by the employee in the particular work context. The decision-making model developed through this study has added to an understanding of disclosure in that it documents a default position of nondisclosure, and describes the importance of a reason for moving away from this default position. It highlights the significance of the interpersonal, and often altruistic, reasons for disclosing at work. In the end, we are left with a paradox. Most participants shared the positive experiences they had with disclosure at work, the support they gained. Yet the default position remains. Sandra perhaps best expressed this paradox:

Because it’s true, you know, like why aren’t we sharing this at work? Because in so many levels they are some of our biggest cheering sections, if you will, are our colleagues. And we, at some level, deny them the opportunity to support us. I say us, it’s … I’m saying it’s me. So we deny them the opportunity to stand up and take our hand to make sure we’re ok because we just haven’t shared. So it makes sense that we share. So I don’t know what the barrier is yet other than…there’s a stigma attached to it at work yet.

Notes

All participant names have been changed to protect confidentiality.

References

Konrad AM, Leslie K, Peuramaki D. Full accessibility by 2025: will your business be ready? Ivey Bus J Online. 2007;71:1–12.

Center C. Law and job accommodation in mental health disability. In: Schultz IZ, Rogers ES, editors. Work accommodation and retention in mental health. New York: Springer; 2011. p. 3–32.

Stuart H. Mental illness and employment discrimination. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2006;19:522–6.

Krupa T, Kirsh B, Cockburn L, Gewurtz R. Understanding the stigma of mental illness in employment. Work. 2009. doi:10.3233/WOR-2009-0890.

Gelb BD, Corrigan PW. How managers can lower mental illness costs by reducing stigma. Bus Horiz. 2008. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2008.02.001.

Goldner E, Bilsker D, Gilbert M, Myette L, Corbière M, Dewa CS. Disability management, return to work and treatment. Healthc Pap. 2004;5:76–90.

Putnam K, McKibbin L. Managing workplace depression: an untapped opportunity for occupational health professionals. Am Assoc Occup Health Nurses J. 2004;52:122–9.

Corbière M, Villotti P, Lecomte T, Bond GR, Lesage A, Goldner EM. Work accommodations and natural supports for maintaining employment. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2014. doi:10.1037/prj0000033.

Corbière M, Villotti P, Toth K, Waghorn G. La divulgation du trouble mental et les mesures d’accommodements: Deux notions pour comprendre le maintien en emploi de personnes aux prises avec un trouble mental grave. L’Encéphale. (in press).

Lesage A, Dewa CS, Savoie JY, Quirion R, Frank J. Mental health and the workplace: towards a research agenda in Canada. Healthc Pap. 2004;5:4–10.

Goffman E. Stigma: notes on the management of spoiled identity. New York: Simon & Schuster; 1963.

Corrigan PW. Dealing with stigma through personal disclosure. In: Corrigan PW, editor. On the stigma of mental illness: implications for research and social change. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004. p. 257–80.

Corrigan PW, Matthews A. Stigma and disclosure: implications for coming out of the closet. J Ment Health. 2003. doi:10.1080/0963823031000118221.

Sandelowski M, Lambe C, Barroso J. Stigma in HIV-positive women. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2004. doi:10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04024.x.

Smith R, Rossetto K, Peterson BL. A meta-analysis of disclosure of one’s HIV-positive status, stigma and social support. AIDS Care. 2008. doi:10.1080/09540120801926977.

DeJordy R. Just passing through: stigma, passing, and identity decoupling in the workplace. Group Organ Manag. 2008. doi:10.1177/1059601108324879.

Scheid TL. Stigma as a barrier to employment: mental disability and the Americans with Disabilities Act. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2005. doi:10.1016/j.ijlp.2005.04.003.

Hernandez B, McDonald K, Divilbiss M, Horin E, Velcoff J, Donoso O. Reflections from employers on the disabled workforce: focus groups with healthcare, hospitality and retail administrators. Empl Responsib Rights J. 2008. doi:10.1007/s10672-008-9063-5.

Beardwood BA, Kirsh B, Clark NJ. Victims twice over: perceptions and experiences of injured workers. Qual Health Res. 2005. doi:10.1177/1049732304268716.

Eakin JM. The discourse of abuse in return-to-work: a hidden epidemic of suffering. In: Mayhew C, Peterson CL, editors. Occupational health and safety: international influences and the “new” epidemics. Amityville: Baywood; 2005. p. 159–74.

Stuart H. Stigma and work. Healthc Pap. 2004;5:100–11.

Britt TW. The stigma of psychological problems in a work environment: evidence from the screening of service members returning from Bosnia. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2000. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2000.tb02457.x.

Lai YM, Hong CP, Chee CY. Stigma of mental illness. Singap Med J. 2001;42:111.

Tajfel H, Turner JC. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In: Worchel S, Austin WG, editors. Psychology of intergroup relations. 2nd ed. Chicago: Nelson-Hall; 1986. p. 7–24.

Hogg MA. Social identity theory. In: Burke PJ, editor. Contemporary social psychological theories. Stanford: Stanford University Press; 2006. p. 111–36.

Ragins BR, Singh R, Cornwell JM. Making the invisible visible: fear and disclosure of sexual orientation at work. J Appl Psychol. 2007. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.4.1103.

Link BG, Phelan JC, Bresnahan M, Stueve A, Pescosolido BA. Public conceptions of mental illness: labels, causes, dangerousness, and social distance. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1328–33.

Creed WED, Scully MA. Songs of ourselves: employees’ deployment of social identity in workplace encounters. J Manag Inq. 2000. doi:10.1177/1056492600000900410.

Clair JA, Beatty JE, MacLean T. Out of sight but not out of mind: managing invisible social identities in the workplace. Acad Manag Rev. 2005;30:78–95.

Bairan A, Taylor GAJ, Blake BJ, Akers T, Sowell R, Mendiola R. A model of HIV disclosure: disclosure and types of social relationships. J Am Acad Nurs Pract. 2007. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7599.2007.00221.x.

Ragins BR. Disclosure disconnects: antecedents and consequences of disclosing invisible stigmas across life domains. Acad Manag Rev. 2008;33:194–215.

Sowell RL, Seals BF, Phillips KD, Julious CH. Disclosure of HIV infection: How do women decide to tell? Health Educ Res. 2003;18:32–44.

Derlega VJ, Winstead BA, Greene K, Serovich J, Elwood WN. Perceived HIV-related stigma and HIV disclosure to relationship partners after finding out about the seropositive diagnosis. J Health Psychol. 2002;7:415–32.

MacDonald-Wilson KL, Russinova Z, Rogers ES, Lin CH, Ferguson T, Dong S, MacDonald MK. Disclosure of mental health disabilities in the workplace. In: Schultz IZ, Rogers ES, editors. Work accommodation and retention in mental health. New York: Springer; 2011. p. 191–217.

Brohan E, Henderson C, Wheat K, Malcolm E, Clement S, Barley EA, et al. Systematic review of beliefs, behaviours and influencing factors associated with disclosure of a mental health problem in the workplace. BMC Psychiatr. 2012. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-12-11.

Chaudoir SR, Fisher JD. The disclosure processes model: understanding disclosure decision-making and post-disclosure outcomes among people living with a concealable stigmatized identity. Psychol Bull. 2010. doi:10.1037/a0018193.

Hudson J. The disclosure process of an invisible stigmatized identity. College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences theses and dissertations. Paper 93. 2011. http://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/93.

Henderson C, Brohan E, Clement S, Williams P, Lassman F, Schauman O, et al. A decision aid to assist decisions on disclosure of mental health status to an employer: protocol for the CORAL exploratory randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatr. 2012. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-12-133.

Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991. doi:10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T.

Glaser BG. Theoretical sensitivity. Mill Valley: Sociology Press; 1978.

Glaser BG. Basics of grounded theory analysis: emergence versus forcing. Mill Valley: Sociology Press; 1992.

Cain R. Stigma management and gay identity development. Soc Work. 1991;36:67–73.

Herman NJ. Return to sender: reintegrative stigma-management strategies of ex-psychiatric patients. J Contemp Ethnogr. 1993. doi:10.1177/089124193022003002.

Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage; 2006.

Derlega VJ, Winstead BA, Gamble KA, Kelkar K, Khuanghlawn P. Inmates with HIV, stigma, and disclosure decision-making. J Health Psychol. 2010. doi:10.1177/1359105309348806.

Greef M, Phetlhu LN, Dlamini PS, Holzemer WL, Naidoo JR, Kohi TW, et al. Disclosure of HIV status: experiences and perceptions of persons living with HIV/AIDS and nurses involved in their care in Africa. Qual Health Res. 2008. doi:10.1177/1049732307311118.

Fesko SL. Disclosure of HIV status in the workplace: considerations and strategies. Health Soc Work. 2001;26:235–44.

Hayward P, Bright JA. Stigma and mental illness: a review and critique. J Ment Health. 1997. doi:10.1080/09638239718671.

Sowell RL, Phillips KD. Understanding and responding to HIV/AIDS stigma and disclosure: an international challenge for mental health nurses. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2010. doi:10.3109/01612840903497602.

Jones AM. The disclosure of severe mental illness in the workplace. Doctoral dissertation. ProQuest Dissertation and Theses database. 2009.

Granger B. The role of psychiatric rehabilitation practitioners in assisting people in understanding how to best assert their ADA rights and arrange job accommodations. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2000;23:215–23.

Rostosky SS, Riggle EDB. “Out” at work: the relation of actor and partner workplace policy and internalized homophobia to disclosure status. J Couns Psychol. 2002. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.49.4.411.

Gregory BT, Harris SG, Armenakis AA, Shook CL. Organizational culture and effectiveness: a study of values, attitudes, and organizational outcomes. J Bus Res. 2009. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2008.05.021.

Thun B. Disability rights frameworks in Canada. J Individ Empl Rights. 2007. doi:10.2190/IE.12.4.g.

Griffith KH, Hebl MR. The disclosure dilemma for gay men and lesbians: “coming out” at work. J Appl Pscyhol. 2002. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.87.6.1191.

Lemieux P, Durand MJ, Hong QN. ‘Supervisors’ perception of the factors influencing the return to work of workers with common mental disorders. J Occup Rehabil. 2011. doi:10.1007/s10926-011-9316-2.

Gallie KA, Schultz IZ, Winter A. Company-level interventions in mental health. In: Schultz IZ, Rogers ES, editors. Work accommodation and retention in mental health. New York: Springer; 2011. p. 295–309.

Schultz IZ, Milner RA, Hanson DB, Winter A. Employer attitudes towards accommodations in mental health disability. In: Schultz IZ, Rogers ES, editors. Work accommodation and retention in mental health. New York: Springer; 2011. p. 325–40.

Stuart H, Arboleda-Flórez J, Sartorius N. Paradigms lost: fighting stigma and the lessons learned. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2012.

Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, Bruffaerts R, Brugha TS, Bryson H, et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in Europe: results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;109(Suppl 420):21–7.

Corbière M, Lesage A, Villeneuve K, Mercier C. Le maintien en employ de personnes souffrant d’une maladie mentale. Sante Ment Que. 2006;31:215–35.

Mohammad A, Schur L, Blanck P. What types of jobs do people with disabilities want? J Occup Rehabil. 2011;21:199–210.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported bythe Work Disability Prevention CIHR Strategic Training Program, through the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Grant(s) FRN: 53909.

Ethical standards

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 (5).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants for being included in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Toth, K.E., Dewa, C.S. Employee Decision-Making About Disclosure of a Mental Disorder at Work. J Occup Rehabil 24, 732–746 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-014-9504-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-014-9504-y