Abstract

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is an issue that affects women across all cultures. It is essential to understand how women could be assisted to prevent and reduce the effects of violence. This systematic review examined studies that made cross-cultural comparisons of differences in help-seeking behaviour of women who have experienced IPV. Databases including the Cochrane Library, PsychInfo and others were searched for literature published between 1988 and 2016. Seventeen articles with a total of 40,904 participants met the inclusion criteria. This review found some differences in the procurement of support across cultural groups. While Caucasian women were more likely to seek assistance from formal services such as mental health and social services, Latina/Hispanic and African-American women were more likely to utilize other types of formal supports such as hospital and law enforcement services. The findings regarding utilization of informal support systems showed mixed results. Overall, the findings of this systematic review suggest that women from culturally diverse minority backgrounds should be educated and encouraged to access support before and after experiencing IPV. Further, potential barriers to help-seeking need to be identified and addressed across women from all cultures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a globally important issue that affects women worldwide [1]. Women subjected to IPV require assistance to reduce the negative consequences of the physical, sexual, psychological, emotional, financial, and religious abuse they experience, and to improve their access to essentials such as food, shelter, and medical treatment [2]. However, the support that women seek and that which is available to them varies markedly across different countries, and cultural and ethnic groups [2]. This review provides a cross-cultural comparison of help-seeking behaviours and barriers to seeking help among women who have experienced IPV.

Prevalence of IPV

The nature of IPV and the complexities associated with ascertaining its true extent leads to some difficulty with obtaining accurate estimates of worldwide prevalence. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated 30% of all women who had been in a relationship had experienced physical and/or sexual violence by their intimate partner [2]. This estimation only encapsulates physical and sexual violence and does not account for the other types of IPV such as psychological, emotional, spiritual, and financial abuse. It is also understood that underreporting of IPV is a limitation of population-based surveys [3]. Therefore, it is possible that the worldwide prevalence of IPV is substantially higher than that reported.

IPV is a term used interchangeably in the literature with partner violence, inter-partner violence, domestic violence, family violence, domestic abuse, spouse abuse, women battering, etc. For this review, IPV will be used and will encompass findings that have incorporated all the different terminologies. Further, since the literature uses a range of terms to explain cultural belongingness, the terms ‘culture’ and ‘ethnicity’ will be used interchangeably in this review.

Lifetime prevalence of IPV perpetrated against women varies across regions with the highest prevalence rates reported in low- and middle-income regions including the Western Pacific (60.0–68.0%), South East Asia (37.7%), Eastern Mediterranean (37.0%) and Africa (36.6%), compared to low- and middle-income regions including the Americas (29.8%) and Europe (25.4%), and high-income regions (such as Australia, Canada, UK, etc.) (23.2%) [2]. Such variability in IPV rates across regional groups suggests that there are specific differences in IPV based on culture and ethnicity.

Cross-cultural prevalence rates are important to consider given the high rate of inter-country movement worldwide. Not only do people migrate to alternate countries permanently for residence but also to seek asylum and reside as temporary refugees. In 2013, the Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA) of the United Nations Secretariat reported an estimate of 232 million migrants globally [4]. They also reported a rise in international migrants worldwide of 50% between 1990 and 2013 [4]. For example, between 1990 and 2013, countries throughout Europe gained 23 million international migrants, originating from other European countries (43%), Asian countries (22%), African countries (18%), and Latin American and Caribbean regions (14%) [4]. Such migration patterns and growth in international migration highlight the extent of cultural diversity that can exist in a country and the importance of examining IPV from a multicultural perspective. This notion is reflected by Guruge et al. who suggest that increasing migration requires healthcare workers to consider and respond to the unique needs of women experiencing IPV in a post-migration context [5].

Effects of IPV

The impact of IPV on women’s health is severe and long-lasting [6]. The WHO reported that 42% of women who have experienced physical or sexual abuse by their partner have also experienced physical injuries [2]. Other adverse effects of IPV include reproductive problems, contraction of sexually transmitted infections and diseases (including HIV and AIDS), elevated stress levels, psychological distress and associated problems (including depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, etc.), suicidality, substance use and, in extreme cases, death [1, 2]. Indeed, compared to women who have not experienced IPV, women who experience IPV are more than twice as likely to experience depression and up to 1.5 times more likely to contract HIV [2, 7]. Given these dire effects of IPV, it is essential to explore whether victims seek help and if there are any barriers to this.

Help-Seeking Behaviour and IPV

It is clear from the underreporting of IPV that, despite the severe effects of IPV, not all women who experience IPV seek help. Help-seeking behaviour can be defined as any behaviour or activity involved in the process of seeking help that is external to the self with regard to “understanding, advice, information, treatment and general support in response to a problem or distressing experience” [8, p. 281]. There are varying estimates of help-seeking behaviour for IPV because of inconsistencies in the recording of requests for assistance; further, informal requests are not recorded by any agency. Therefore, it is necessary to explore help-seeking behaviour and the barriers.

Formal help-seeking behaviour includes seeking assistance from doctors, psychologists, psychiatrists, social workers, counsellors, police, lawyers, etc., while informal help-seeking behaviour involves obtaining support from family members, friends, neighbours, online resources, etc. A secondary survey analysis by Kaukinen [9] in the USA reported that 30% of IPV survivors utilised police services, while 52% sought informal support from family members or friends, 20% from psychiatrists and doctors, and only 5% utilised social workers. Meanwhile, a re-analysis of a national survey of Canadian households revealed that 66% of IPV survivors reported using at least one kind of formal service in response to IPV while over 80% reported using informal supports [10].

Help-seeking behaviour for IPV varies markedly across different populations and rates may be lower among migrant and minority cultural or ethnic groups [11, 12]. Although Hyman et al. [11] found similar rates of IPV disclosure and reporting to the police among non-Caucasian and Caucasian women in Canada, non-Caucasian women were found to have sought help for IPV from family, friends, or neighbours more often than Caucasian women. The greatest discrepancy was found between the utilisation of social services: non-Caucasian women were less likely to seek formal help for IPV compared to Caucasian women (35.3 and 51.4%, respectively) [11]. Similarly, Barrett and St. Pierre [10] found that non-Caucasian status was associated with less use of formal and informal support services.

Ingram [13] explored help-seeking rates among Latino and non-Latino IPV survivors and found that Latina women disclosed their experiences of IPV to family members more often than non-Latina women, while non-Latina women disclosed to health care workers, clergy, and shelter services more often than Latina women. Furthermore, Cho [14] examined differences in service utilisation between Latino and Asian groups and found that Latino survivors reported significantly more use of mental health and support services than Asian survivors [14]. Similarly, Cho and Kim [15] explored help-seeking rates of Asian IPV survivors in comparison to those of Latino, African-American, and Caucasian survivors and found that Asian survivors were less likely to use mental health services. Overall, these patterns suggest that the help-seeking behaviours of women who are experiencing or have experienced IPV are not identical across cultural groups; it is therefore necessary to examine the barriers that prevent different groups from seeking help.

Barriers to Help-Seeking for IPV

Barriers to help-seeking are evident in all groups of women experiencing IPV. The most commonly reported hindrances include fears of further violence from a partner and for the safety of their children, an unawareness of or isolation from available support services, and the shame and stigma associated with reporting their IPV experiences [6, 11, 16].

Hilbert and Krishnan [17] postulate that there are two levels of barriers to help-seeking for IPV survivors: (a) the sociodemographic characteristics of the help-seeker, and (b) cultural norms and customs integrated into help-seeking. For example, an IPV survivor may not seek help because they are limited by the language that they speak, or because IPV is considered a private matter and thus disclosure is not culturally accepted. A second theory by Overstreet and Quinn pertains to the IPV stigmatization model, which identifies three components of stigma that can impede on help-seeking behaviour for those experiencing IPV. This includes cultural stigma, stigma internalisation, and anticipated stigma [18]. Cultural stigma refers to the social beliefs and attitudes that devalue the legitimacy of people experiencing IPV, while stigma internalisation refers to the process and extent to which people experiencing IPV believe that negative stereotypes about experiencing IPV represent themselves. Anticipated stigma refers to victims’ concern about the consequences of other people becoming aware of their abuse [18]. This model suggests that women who experience IPV can be negatively affected by the sociocultural context in which the IPV occurs.

In addition to barriers shared by all cultural groups, there are variations in the challenges to gaining assistance across migrants and ethnic minority groups. Bent-Goodley [19] identified that “culture shapes experiences, creates perceptions, and impacts how we think, feel, absorb, refine, justify and solidify information” (p. 92). This understanding of unique cultural experiences is fundamental to providing culturally appropriate programs and interventions for IPV survivors. Minority ethnic groups and migrant women often report a dearth of culturally appropriate services as a barrier to help-seeking along with the lack of knowledge about available services [20]. One barrier specific to migrant women is their legal status in the country of residence; often, the fear of deportation leads them to succumb to their abusive experiences and not seek assistance [20].

There are specific concerns reported among some ethnic groups that lead to underreporting of the crime. For example, the cultural norms associated with the acceptance of physical abuse from a male partner prevent Asian women from seeking assistance [6]; these women also belong to a culture where female submissiveness and stoicism are valued and family conflict and dysfunction are considered shameful [21]. Hence the reporting of family violence in such cultures is not encouraged. Similarly, Latina women consider the cultural value of ‘familismo’ (family unity and individual devotion to family) to be central as a barrier to help-seeking [21]. These women also identify language difficulties between themselves and service providers as another barrier to help-seeking for IPV [22]. Such findings suggest that help-seeking behaviour and barriers to help-seeking are not consistent across cultural groups and that ethnicity and cultural background are essential for understanding women’s responses to IPV. This systematic review was conducted to examine differences in help-seeking behaviour among victims of IPV from different cultural backgrounds.

Method

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

This section provides details of the search strategies used for this review. Databases were comprehensively searched over a 28-year period from 1988 until 30 August, 2016. Peer-reviewed articles were identified from the following databases: Academic Search Complete, AMED, CINAHL Complete, Criminal Justice Abstracts with Full Text, E-Journals, Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition, MEDLINE, MEDLINE Complete, PsycARTICLES, PsycEXTRA, PsycINFO, Psychology and Behavioural Sciences Collection, and Social Work Abstracts. The Cochrane database and relevant reference lists of articles were also searched. Please refer to Table 1 for details of the terms used in database searches for literature.

Inclusion Criteria

Studies were required to have made a comparison between at least two ethnic groups and should have reported the results for estimates of help-seeking behaviour to be included in this study. Participants needed to have been female, aged over 18 years, and have experienced IPV.

Exclusion Criteria

Studies that included male participants or children under 18 years of age, examined help-seeking behaviour and IPV in only one ethnic group, or did not distinguish rates of help-seeking between ethnic groups were excluded from the current review.

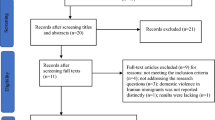

As illustrated in Fig. 1, the search yielded 1331 results after duplicates were removed. After screening the titles and abstracts of these articles, 1240 records were removed based on the exclusion criteria. Of the remaining 91 articles, the full text was screened to determine whether they met the inclusion criteria. Overall, 17 articles met the criteria and were included in this review.

Reproduced with permission from Ref. [23]

The PRISMA flow diagram.

Results

Study Design Characteristics

All the studies that met the selection criteria were conducted in North America, except for one that also included the USA Virgin Islands. Most studies used a cross-sectional design (82%); a cohort (6%), case control (6%), and longitudinal (6%) design was each used across three studies. Details of the studies are provided in Table 2.

Sample

Some of the studies collected primary data but the majority conducted secondary data analysis. Nine studies (52%) had a sample size over 1000, four studies (24%) had a sample size between 300 and 1000, and four (24%) studies had a sample size under 300. Across the 17 studies, a few ethnic groups were explored: 12 included Hispanic/Latina women; 15 included African-American women; 14 included Caucasian women; three included Asian/Pacific Islander women; and ‘other’ (not specified in the studies) women were identified in five studies. Only one study included distinct sub-ethnic groups within a broader ethnic group. In total, the 17 studies included 40, 904 participants.

Measures of IPV

The reviewed studies used an assortment of IPV measures. These included police and hospital reports, social service and refuge shelter reports, and self-identification by women experiencing IPV in response to either explicit survey questionnaire or interview questions. Five studies used reports from police, hospitals, and refuge shelters to measure IPV including three [27, 39, 40] that used police reports and the study by El-Khoury et al. [27] also using refuge shelter reports and that by Lipsky et al. [39] also adding hospital reports to their measure. Three other studies [25, 32, 39] used only hospital reports as a measure of IPV. Apart from these, most studies used self-reports to measure IPV including three [26, 31, 36] that used self-reports in response to interview questions. For example, Durfee and Messing [26] asked respondents whether they had experienced physical, sexual, verbal, or economic abuse, and whether they had ever been pregnant or had a miscarriage while in an abusive relationship. Similarly, Gondolf et al. [31] asked respondents about physical abuse, verbal abuse, child abuse, injury and previous abuse; Henning and Klesges [36] asked respondents about current offense circumstances, severity of prior abuse, and current safety.

A further three studies [24, 30, 38] measured IPV using self-reports in response to nationwide survey questionnaires including: the National Violence Against Women Survey (NVAWS) [30], which measured physical abuse, sexual abuse, stalking, psychological abuse, cumulative abuse; the National Crime Victimisation Survey (NCVS) [24], which collected information about victims, offenders, and offense circumstances; and the 2002 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) [38], which asked a single question: “How many times during the past 12 months did your spouse or partner hit or threaten to hit you?”.

The six other studies used participants’ responses to psychological questionnaires. Specifically, four studies [33, 37, 42, 43] used different revisions of the Conflict Tactic Scale (CTS) by Straus [34] to measure IPV. The CTS is a widely used and validated scale that consists of physical abuse and sexual abuse items [34]. The study by Rodriguez et al. [22] used the Abuse Assessment Screen [44] to measure current and previous experiences of physical and sexual forms of IPV, and Sabri et al. [41] used The Severity of Violence against Women Scale and Women’s Experiences of Battering to assess IPV experiences.

Measures of Help-Seeking Behaviour

All 17 studies detailed their measure of help-seeking behaviour, however, these measures varied, and the reliability and validity of the measures are unavailable. Most of the measures relied on self-report (in response to nationwide surveys and interviews) by women who had previously experienced or were currently experiencing IPV. Meanwhile, Ahmed and McCaw [25] and Lipsky et al. [39] used hospital reports to measure emergency service utilisation, and Grossman and Lundy [32] used social service reports to measure self-referral for domestic violence programs.

Six studies [22, 26, 31, 36, 37, 43] relied on self-reports of help-seeking behaviour in response to interview questions. For example, Durfee and Messing [26] asked respondents about police involvement in IPV incidents, receipt of medical attention, and disclosure of IPV to a medical professional. Similarly, Rodriguez et al. [22] examined participants’ disclosure of IPV to a clinician. Gondolf et al. [31] extended on this by assessing informal and formal sources of help utilized prior to the shelter and care sought for injury, as well as services obtained while in the shelter and those to be continued after leaving the shelter. Henning and Klesges [36] included information on formal counselling and support service utilisation, while Lipsky et al. [37] provided data on health and social service utilisation. Yoshioka et al. [43] on the other hand measured disclosure of abuse (to family members, friends, or professionals) and support received.

Most studies measured help-seeking behaviour using survey questionnaires. Three studies [24, 30, 38] assessed responses in the nationwide survey questionnaires including: the NVAWS [30] which asked respondents open and closed-ended questions about their help-seeking behaviours in response to the most recent incident of physical abuse; the NCVS [24] which examined whether participants reported the crime to the police; and the NSDUH [38] which measured emergency department utilisation. Three other studies [40,41,42] examined participants’ response to items on survey questionnaires developed by the authors. For example, West et al. [42] measured utilization of formal and informal resources such as friends, relatives, shelter, a psychologist, clergy, healer, lawyer, and police, while Macy et al. [40] measured formal help-seeking only. Similarly, Sabri et al. [41] measured utilisation of mental health resources including a counsellor, therapist and caseworker.

Two of the studies [27, 33] used psychological measures of help-seeking behaviour: (a) El-Khoury et al. [27] selected items from two indices including The Intimate Partner Violence Strategies Index [28] and The Intimate Partner Violence Coping Index [29] to measure six types of help-seeking behaviour: formal, informal, safety planning, resisting, placating, and legal strategies; and (b) Hamberger et al. [33] used the Physician Assessment and Treatment of Abuse Inventory [35] to measure care sought for physical injury and emotional support sought for abuse-related stress. Thus, a range of measures were used across the studies to assess the experience of abuse and the nature of assistance sought.

Risk of Bias

Because most studies [22, 24, 26, 27, 30,31,32,33, 36,37,38, 40,41,42,43] used self-report measures to obtain details of help-seeking behaviour, there is a high risk of report bias. This bias may have been exacerbated in studies where women were interviewed in person and they did not want to reveal the nature of their abuse or to whom they reported it because of stigma and cultural norms. Further, some studies [22, 30, 41] asked women about prior IPV experiences, thus resulting in risk of recall bias. There is also a high risk of sampling bias as some studies [26, 30, 33] used a convenient sample. It is therefore important to interpret the results of these studies with caution.

Key Findings

Table 1 presents a summary of study populations, designs, measures, and key results from the 17 articles. We reviewed the literature findings in relation to the cross-cultural comparisons of help-seeking behaviour and IPV. Nine of the studies [25,26,27, 30,31,32, 36, 37, 42] reported that Caucasian women were more likely to seek support for IPV compared to African-American and Hispanic/Latina women. For example, Henning and Klesges [36] reported that as a single predictor, Caucasian women were three times more likely to seek help for IPV compared to African-American women. In consonance, Lipsky et al. [37] found that compared to Hispanic women, non-Hispanic Caucasian women were more likely to use domestic violence services and housing assistance. Similarly, Caucasian women also self-referred to domestic violence programs significantly more than African-American and Hispanic women [31, 32] and sought a protection order for IPV to a greater extent [26]. Furthermore, compared to Hispanic women, Caucasian women were nine times more likely to use emergency services and African women six times more likely [37].

Although the studies reported above showed a trend that Caucasian women were more inclined to seek help compared to non-Caucasian women, a few studies showed the opposite. Six studies [22, 24, 27, 30, 38, 39] found African-American and Hispanic/Latina women were more likely to seek support for IPV compared to Caucasian women. These studies found that Hispanic and African-American women displayed greater rates of hospitalisation, police involvement, and visits to a clinician. For example, Lipsky and Caetano [38] found that the Hispanic women were three times more likely to be hospitalised in the emergency department because of IPV compared to Caucasian women. Lipsky et al. [37] also reported that overall healthcare utilisation for IPV was greater among African-American women. Indeed, police reporting was higher among African-American (46.2%) and Hispanic women (37.7%) compared to Caucasian women (16.2%) [39]; African-American women were more likely to disclose IPV to a clinician [22, 33]. Similarly, Ackerman and Love [24] found that that relative to Caucasian women, Latina women were 83% more likely; African-American women were 92% more likely; and other non-Latina women were 36% more likely to notify police when subjected to IPV. Flicker et al. [30] also found that Latina women and African-American women were more likely to seek police help and African-American women were more likely to seek orders of protection. Thus, there were mixed statistics in the rate of help-seeking behaviour from primary health care services and law enforcement across different cultural groups.

When considering the utilisation of mental health services, the studies found that Latina and African-American women were less likely to seek such assistance compared to Caucasian women who had experienced IPV. Specifically, studies showed that Caucasian women were more likely to approach a mental health counsellor than Latina women [25] and African-American women [27, 30]. Further, West et al. [42] also found Anglo-Saxon women were five times more likely to seek assistance from psychologists after experiencing IPV compared to African-American and Latina women.

When examining the role of informal sources of help, Yoshioka et al. [43] found that South Asian and Hispanic women were more likely to seek support from family members or a friend than African-American women. It was also found that overall, African-Caribbean women were less likely to use any resource to cope with IPV compared to African-American women with mixed descent [41] and that women born outside the USA were less likely than USA-born women communicate in any manner about the abuse [22]. Similarly, studies [30, 42] examining the use of informal support among Latina women found that they were less likely to ask friends or family for support compared to Caucasian women. Finally, in El-Khoury’s study [27], they found significantly more African-American women (90.7%) used prayer to cope with IPV compared to Caucasian women (76.5%). In contrast to the several studies that have found cross-cultural differences in help-seeking behaviour, two studies [33, 40] reported no significant differences when comparing the level of assistance sought between cultural groups.

In summary, the results are varied: a majority of the studies found Caucasian women were more likely to seek support for IPV compared to African-American and Hispanic/Latina women [25,26,27, 30,31,32, 36, 37, 42]; other studies however reported that African-American and Hispanic/Latina women were more likely to seek support for IPV compared to Caucasian women [22, 24, 27, 30, 38, 39]. A few studies also reported differences between African-American, Hispanic/Latina, and South Asian women [37, 43], as well as differences among African women. Thus, these results demonstrate that help-seeking behaviour for IPV survivors is not uniform across cultural groups and sometimes within cultural groups.

Discussion

This review explains the extent to which cultural background is associated with the procurement of services to manage the effects of IPV. The findings from this systematic review illustrate the trends and disparities found within the literature in relation to rates of help-seeking behaviour for cultural groups. The ensuing sections will discuss the findings between the cultural groups in light of comparisons made in help seeking behaviour between Caucasian women and African-American, Hispanic/Latina, and South-Asian women.

There are considerable differences between cultural groups in relation to help-seeking behaviour for IPV. The majority of studies [25,26,27, 30,31,32, 36, 37, 42] demonstrated that Caucasian women would seek assistance for IPV more so than African-American or Hispanic/Latina women. Specifically, they were more ready to request help from domestic violence services and programs compared to African-American and Hispanic/Latina women [26, 31, 32, 37]. This difference could be due to the barriers faced by culturally diverse minority women in accessing help. For example, Raj and Silverman [20] suggested a lack of knowledge about available services and the dearth of culturally appropriate services as possible barriers for minority ethnic and migrant women. Another potential barrier to seeking help for IPV survivors is their migrant status. Rodriguez et al. [22] found that women born outside the USA are less likely to disclose abuse to a clinician than women born in the USA. These findings are supported by Ingram [13] who also found that significantly less migrant Latina survivors than non-immigrant non-Latino survivors contacted formal support services for IPV. Such findings echo the theory by Hilbert and Krishnan [17] that cultural norms and customs may prevent survivors of IPV to disclose their abusive experiences and that those same norms may be associated with the acceptance of physical abuse, preventing the procurement of assistance [6]. This highlights the importance of migrant status and cultural norms in help-seeking behaviour after abuse. The findings further corroborate Overstreet and Quinn’s [18] theory that cultural stigma can obstruct victims of IPV from reaching for help.

The findings from some studies in the present review show that African-American and Hispanic/Latina women are more likely to use the assistance of primary health care services and law enforcement [22, 24, 27, 30, 38, 39] compared to Caucasian women. Specifically, hospitalization rates were higher [38] along with increased police reporting [24, 30, 39] among these groups. Some of the reasons for the increased rates of hospital and police services access could be that the samples included in the relevant studies were taken from hospital [39] or police reports [27, 39] of women who experienced IPV. Such studies show a spike in some of the ethnic groups such as Hispanic women utilizing such services as their sampling technique did not consider those who did not access such services. However, the higher hospitalization rates of African-American and Hispanic women compared to Caucasian women may suggest that the former groups are likely experiencing more severe abuse that may require care from medical professionals. It is therefore of concern that these ethnic groups are forced to secure assistance at emergency departments because of the severity of their injuries even though they have previously not shown a readiness to seek help. These findings also suggest that healthcare workers should be cognizant and trained to respond to the unique needs of culturally diverse minority women [5].

This systematic review indicates that African-American and Hispanic/Latina women were less likely to seek assistance from mental health professionals compared to Caucasian women [25, 27, 30, 42]; Latina women also displayed a reduced rate of procuring support from social services and support programs compared with the two other groups [31, 32, 37]. These findings could be related to the concept of ‘familismo’ among Latina women that acts as a barrier to seeking help. The relevance of the sociocultural context, in particular, ‘anticipated stigma’ has also been attributed as a factor in women who experience IPV not reporting it because of the societal consequences of others becoming aware of their abuse [18]. Therefore, culturally intrinsic factors can play a significant role in culturally diverse women seeking assistance.

In examining the impact of English language proficiency of service utilisation, Ahmed and McCaw [25] observed that women who spoke English had a higher predicted probability of utilising mental health services than women who spoke Spanish or languages other than English. This finding that language proficiency could reduce help-seeking behaviour coincides with Hilbert and Krishnan’s [17] postulate that IPV survivors may not seek help because they are limited by the language they speak. It is again concerning that there are higher rates of hospital utilization but not mental health support among certain ethnicities. To enhance help-seeking rates, it is recommended that culturally intrinsic intervention programs be developed and promoted for ethnic minority groups.

The findings in relation to the use of informal support systems show mixed results in that some studies [43] demonstrated that some groups are more likely to solicit assistance from family and friends, while others [30, 42] showed that minority groups do not request help even from those close to them. Gaining assistance from family members and friends is common among members of the South Asian community especially because of the reluctance to take assistance from outside sources [45] and also because of the culturally prescribed roles of brothers to support their sisters [46, 47]. Finally, it appears that when people who are abused do not want to solicit support from anyone, they resort to their spirituality to cope with the situation [27]. It was found that more African women sought support from a minister compared to Caucasian and Hispanic/Latina women and made more use of prayer as a support mechanism when abused compared to Caucasian women [27, 31]. These findings may suggest that they may not be gaining adequate support to address the violence but that their spirituality provides a means of coping and not exposing themselves to the cultural stigma associated with their community becoming aware of the abuse [18].

While the above discussion provides some insight into help-seeking behaviour for IPV between cultural groups, two studies [33, 40] did not note any distinct patterns. This variation in the finding could be a result of the sample characteristics within these studies. For example, the study by Hamberger et al. [33] was limited in having a small convenience sample, and Macy et al. [40] included a small sample size of specific ethnic groups.

Limitations

Despite the rich cross-cultural findings about variations in help-seeking behaviour among women who have experienced IPV, we need to note limitations of the present systematic review. First, the majority of the studies included in this review were limited in the inclusion of cultural groups as they only explored differences in help seeking behaviour based on broad ethnic groups. For example, women who were from several countries were all classified as Latina, despite having potential cultural differences. As such, the findings are difficult to generalise to the smaller ethnic groups. Furthermore, although the studies in the systematic review examined rates of help-seeking, very few explicitly considered barriers to help-seeking specific to ethnicity. The discrepancy in some of the findings could be a result of studies including different populations of abused women: for example, Lipsky et al. [37] obtained data from a case-control emergency department setting, whilst Lipsky and Caetano [38] conducted a secondary analysis on a national survey, and Rodriguez et al. [22] conducted telephone interviews with a random sample. Another constraint in the applicability of findings is that all the included studies were conducted in North America (except 1); this limits the generalisability to other ethnic groups across the world. It is therefore recommended that some of the findings be interpreted with caution.

Conclusion

While considering the limitations, this systematic review provides evidence for differences in seeking assistance among women who have experienced IPV based on their cultural background. The findings highlighted that culturally diverse minority groups may be limited in their help-seeking behaviour because of their cultural norms, lack of knowledge about available services and the dearth of culturally appropriate support programs. It is also evident that despite their reluctance to seek assistance, minority groups such as Hispanic/Latina and African-American women are more likely to be hospitalized; this suggests that they are perhaps more prone to experiencing the serious effects of IPV. While some cultural groups may be willing to access support from family and friends, the findings show that others may not. Cultural values such as ‘familismo’ and stigma from their communities may prevent them from revealing their abuse.

With an increased understanding of the importance of cultural background in help-seeking behaviour, it is necessary to educate people from all cultural groups about the importance of procuring assistance as early as possible in their intimate relationships to prevent and reduce violence. It is also recommended that health and support services cater to the unique needs of migrant and culturally diverse minority groups by developing suitable programs. Communities also need to be educated about the importance of encouraging those within their cultural groups to access support services without stigmatizing them.

Further research should examine the help-seeking behaviour of women from other cultural groups around the world. With increasing rates of inter-country migration, it is essential to understand the cultural values and norms of various ethnicities and how this may influence their readiness to obtain assistance to ameliorate the effects of IPV. We also need to develop an enhanced understanding of ways to prevent violence and encourage those who become a victim to it to access support.

References

Ellsberg M, Jansen HM, Heise L, Watts CH, García-Moreno C. Intimate partner violence and women’s physical and mental health in the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence: an observational study. Lancet. 2008;371(9619):1165–72.

World Health Organization. Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

World Health Organization. Preventing intimate partner and sexual violence against women: taking action and generating evidence. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2010.

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. International migration report 2013. New York: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division; 2013.

Guruge S, Khanlou N, Gastaldo D. Intimate male partner violence in the migration process: intersections of gender, race and class. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(1):103–13.

Rodriguez MM, Valentine JM, Son JB, Muhammad MM. Intimate partner violence and barriers to mental health care for ethnically diverse populations of women. Trauma Violence Abus. 2009;10(4):358–75.

White ME, Satyen L. Cross-cultural differences in intimate partner violence and depression: a systematic review. Aggress Violent Behav. 2015;24:120–30.

Cornally N, McCarthy G. Help-seeking behaviour: a concept analysis. Int J Nurs Pract. 2011;17(3):280–8.

Kaukinen C. The help-seeking strategies of female violent-crime victims: The direct and conditional effects of race and the victim-offender relationship. J Interpers Violence. 2004;19(9):967–90.

Barrett B, St. Pierre MT: Variations in women’s help seeking in response to intimate partner violence: findings from a Canadian population-based study. Violence Against Women 2011;17(1):47–70.

Hyman I, Forte T, Du Mont J, Romans S, Cohen MM. Help-seeking behavior for intimate partner violence among racial minority women in Canada. Women’s Health Issues 2009;19(2):101–8.

Raj A, Silverman JG. Domestic violence help-seeking behaviors of South Asian battered women residing in the United States. Int Rev Victimol. 2007;14(1):143–70.

Ingram EM. A comparison of help seeking between Latino and non-Latino victims of intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women. 2007;13(2):159–71.

Cho H. Intimate partner violence among Asian Americans: risk factor differences across ethnic subgroups. J Fam Violence. 2012;27(3):215–24.

Cho H, Kim W. Intimate partner violence among Asian Americans and their use of mental health services: comparisons with White, Black, and Latino victims. J Immigr. Minor Health. 2012;14(5):809–15.

Du Mont J, Hyman I, O’Brien K, White ME, Odette F, Tyyskä V. Factors associated with intimate partner violence by a former partner by immigration status and length of residence in Canada. Ann Epidemiol. 2012;22(11):772–7.

Hilbert JC, Krishnan SP. Addressing barriers to community care of battered women in rural environments: creating a policy of social inclusion. J Health Soc Policy. 2000;12(1):41–52.

Overstreet NM, Quinn DM. The intimate partner violence stigmatization model and barriers to help seeking. Basic Appl Soc Psychol. 2013;35(1):109–22.

Bent-Goodley TB. Health disparities and violence against women: why and how cultural and societal influences matter. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2007;8(2):90–104.

Raj A, Silverman J. Violence against immigrant women: the roles of culture, context, and legal immigrant status on intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women. 2002;8(3):367.

Bauer H, Rodriguez M, Quiroga S, Flores-Ortiz Y. Barriers to health care for abused Latina and Asian immigrant women. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2000;11(1):33–44.

Rodríguez M, Sheldon W, Bauer H, Pérez-Stable E. The factors associated with disclosure of intimate partner abuse to clinicians. J Fam Pract. 2001;50(4):338–44.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(6):e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed1000097.

Ackerman J, Love TP. Ethnic group differences in police notification about intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women. 2014;20(2):162–85.

Ahmed AT, McCaw BR. Mental health services utilization among women experiencing intimate partner violence. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(10):731–8.

Durfee A, Messing J. Characteristics related to protection order use among victims of intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women. 2012;18(6):701–10.

El-Khoury MY, Dutton M, Goodman LA, Engel L, Belamaric RJ, Murphy M. Ethnic differences in battered women’s formal help-seeking strategies: a focus on health, mental health, and spirituality. Cult Divers Ethn Minor Psychol. 2004;10(4):383–93.

Goodman LA, Dutton MA. Women’s intimate partner violence strategy index: development and uses. Paper presented at the Seventh International Family Violence Research Conference 2001, Durham, NH.

Goodman LA, Dutton MA, Weinfurt K, Cook S. The intimate partner violence strategies index: development and application. Violence Against Women. 2003;9:163–86.

Flicker SM, Cerulli C, Zhao X, Tang W, Watts A, Xia Y, Talbot NL. Concomitant forms of abuse and help-seeking behavior among White, African American, and Latina women who experience intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women. 2011;17(8):1067–85.

Gondolf EW, Fisher E, McFerron J. Racial differences among shelter residents: a comparison of Anglo, Black, and Hispanic battered. J Fam Violence. 1988;3(1):39–51.

Grossman SF, Lundy M. Use of domestic violence services across race and ethnicity by women aged 55 and older. Violence Against Women. 2003;9(12):1442–52.

Hamberger L. Racial differences in battered women’s experiences and preferences for treatment from physicians. J Fam Violence. 2007;22(5):259–65.

Straus M. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: the conflict tactics (CT) scales. J Marriage Fam. 1979;41(1):75–88.

Hamberger LK, Ambuel B, Marbella A, Donze J. Physician interaction with battered women: the women’s perspective. Arch Fam Med. 1998;7:575–82.

Henning KR, Klesges LM. Utilization of counseling and supportive services by female victims of domestic abuse. Violence Vict. 2002;17(5):623–36.

Lipsky S, Caetano R, Field CA, Larkin GL. The role of intimate partner violence, race, and ethnicity in help-seeking behaviors. Ethn Health. 2006;11(1):81–100.

Lipsky S, Caetano P. The role of race/ethnicity in the relationship between emergency department use and intimate partner violence: findings from the 2002 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(12):2246–52.

Lipsky S, Caetano R, Roy-Byrne P. Racial and ethnic disparities in police-reported intimate partner violence and risk of hospitalization among women. Women’s Health Issues. 2009;19(2):109–18.

Macy RJ, Nurius PS, Kernic MA, Holt VL. Battered women’s profiles associated with service help-seeking efforts: Illuminating opportunities for intervention. Soc Work Res. 2005;29(3):137–50.

Sabri BB, Bolyard RR, McFadgion AL, Stockman JK, Lucea MB, Callwood GB, Coverston CR, Campbell JC. Intimate partner violence, depression, PTSD, and use of mental health resources among ethnically diverse Black women. Soc Work Health Care. 2013;52(4):351–69.

West CM, Kantor GK, Jasinski JL. Sociodemographic predictors and cultural barriers to help-seeking behavior by Latina and Anglo American battered women. Violence Vict. 1998;13(4):361–75.

Yoshioka MR, Gilbert L, El-Bassel N, Baig-Amin M. Social support and disclosure of abuse: comparing South Asian, African American, and Hispanic battered women. J Fam Violence. 2003;18(3):171–80.

Soeken K, Parker B, McFarlane J, Lominack MC. The abuse assessment screen: a clinical instrument to measure frequency, severity, and perpetrator of abuse against women. In: Campbell JC, editor. Empowering survivors of abuse: health care for battered women and their children. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1998.

Rao VN, Rao VVP, Fernandez M. An exploratory study of social support among Asian Indians in the U.S.A. Int J Contemp Soc. 1990;27(3/4):229–45.

Das AK, Kemp SF. Between two worlds: counseling South Asian Americans. J Multicult Couns Dev. 1997;25(1):23–33.

Kolenda P. Sibling relations and marriage practices: a comparison of north, central, and south India. In: Nuckolls CW, editor. Siblings in South Asia: brothers and sisters in cultural context. New York: Guilford Press; 1993.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Ethics approval to conduct the study was provided by the Deakin University Human Research Ethics Committee.

Informed Consent

For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Satyen, L., Rogic, A.C. & Supol, M. Intimate Partner Violence and Help-Seeking Behaviour: A Systematic Review of Cross-Cultural Differences. J Immigrant Minority Health 21, 879–892 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-018-0803-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-018-0803-9