Abstract

To examine two healthcare models, specifically “Primary Medical Care” (PMC) and “Primary Health Care” (PHC) in the context of immigrant populations’ health needs. We conducted a systematic scoping review of studies that examined primary care provided to immigrants. We categorized studies into two models, PMC and PHC. We used subjects of access barriers and preventive interventions to analyze the potential of PMC/PHC to address healthcare inequities. From 1385 articles, 39 relevant studies were identified. In the context of immigrant populations, the PMC model was found to be more oriented to implement strategies that improve quality of care of the acute and chronically ill, while PHC models focused more on health promotion and strategies to address cultural and access barriers to care, and preventive strategies to address social determinants of health. Primary Health Care models may be better equipped to address social determinants of health, and thus have more potential to reduce immigrant populations’ health inequities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Effective and timely access to quality primary care is a critical resource for the health of immigrants [1]. In this study of healthcare models, we defined immigrants broadly, see “Box 1”. Numerous studies reveal that immigrants, excluding refugees, arrive in better health than the general population [2, 3]. Their health status, however, tends to decline and converge with that of the native population during the integration process [4–6]. Refugees may have unique socio-demographic characteristics and suffer more infectious diseases, but we included them because, like other migrant groups, they also face barriers accessing and using healthcare services [7, 8].

“Health inequities are when inequalities in health are deemed avoidable, remediable, and unfair”[9]. The definition and measurement of health inequity requires a normative decision about social justice and fairness that may vary based on context [10]. Immigrants face barriers accessing health care [11–14]. Factors that may contribute to inequities include forced migration, limited official language proficiency, country of origin and education level, and other social determinants of health [1]. Limited education and health literacy are potential sources of immigrant health inequity [15]. Patient-practitioner interactions can build trust in a new system [16], but many barriers may intercede [17–19].

Globally, two broad models have emerged to provide primary care to immigrant populations (and the population in general); primary medical care (PMC) and primary health care (PHC) [20, 21]. Both incorporate health services and the two models commonly coexist in health systems [22, 23]. We used the framework described by Muldoon et al. [20] to distinguish the two models in providing health care to immigrants’ populations. Muldoon et al. describes primary care (consider as PMC in this study), “a narrower concept of ‘family doctor –type’ services delivered to individuals”; and PHC “describes a model of health policy and service provision that includes both services to individuals and population level public health –type functions” [20] Hence, we defined PMC as the medically-oriented model and PHC as a community-oriented model. (see “Box 2”).

PHC models are more common in developing countries, while developed nations are more focused on the PMC model [24, 25], but these models frequently coexist in both development contexts. In Canada, for example, two models of primary care are recognized: a community-oriented approach, and a professional approach [26], and a set of attributes have been defined to characterize these models [27]. Expanding healthcare models may be helpful in responding to existing access and healthcare inequities among immigrant populations. The goal of this review was to examine how these two primary care models, PMC and PHC, deliver healthcare to address immigrants’ health needs and how it may affect health inequities.

Methods

We used a systematic scoping review [28]. We followed the Arksey and O’Malley’s scoping review framework [29] which includes: (a) identifying the research question; (b) identifying relevant studies (including a quality assessment in this step); (c) selecting studies; (d) charting data; (e) collating, summarizing, and reporting results.

Identifying Relevant Literature

The research question that guided this review was: what are the strengths and limitations of the two primary care models, in delivering healthcare to immigrants to address their health needs? The review focused on the health problems addressed by these models, the types of prevention strategies used, the types of barriers that the models targeted and the interventions used to target them.

To identify relevant publications, the search strategy included terms in three domains: primary care or primary health care, immigrants, and model of care; following the selection criteria defined in “Box 3”. The search terms were: ‘primary care’ OR ‘primary health care’ AND ‘immigrant’ OR ‘migrant’ and ‘model of care’. Medical subject heading (MeSH) terms and key words derived from those domains were used, (see Online Appendix 1).

With the assistance of a librarian, an electronic search was conducted in the following eight databases: CINAHL, Cochrane Library, EBM Reviews, Embase, MEDLINE, PsychINFO, Web of Science and Global Health. The electronic searches included English language articles, published from January 1st, 1990 to November 30th, 2013. In addition, several journals and international resources or organizations relevant to migrants’ health and health care were purposefully hand searched for same time period, using the keywords: ‘primary care’ or ‘primary health care’ and ‘immigrant’ or ‘migrant’ and ‘model of care’. (Online Appendix 1) We screened, assessed full texts, and imported articles into Endnote X7.

Quality Appraisal

We critically appraised the selected documents using validated tools to ensure a minimum quality of the evidence [30, 31]. To that end, the studies were classified in three categories: quantitative, qualitative and systematic review. A fourth category that included other types of publications (conceptual papers, technical or policy reports, and non-peer reviewed) was included and a special quality assessment tool was developed for this, based on other appraisal guidelines [32–34]. We adapted a ten items checklist for each type of study based on key attributes (see Online Appendix 2). If seven or more items met the criteria, then we deemed the study of good quality and considered for further analysis, otherwise, they were excluded.

Data Extraction and Charting

The studies reviewed were classified as either of two models—PMC or PHC—guided by the principle framework outlined by Muldoon et al., based on the differences described in “Box 2”. Briefly, when the study described family doctor—type measures delivered to individuals inside health services, it was classified as PMC; and when the study included interventions beyond the health services to reach out to the community and/or involved other social services (e.g. legal, food or school programs, transportation, etc.), then it was considered as PHC.

Data Analysis

We used a framework synthesis approach [35] to organize and synthesize the data and to discuss the results. For the purpose of describing and discussing the results, we focused on three dimensions of the health services described as follows: (a) type of health service provided, (b) type of barriers addressed; and (c) type of preventive measures applied (see details in Online Appendix 3). For the type of barrier or facilitator to access nine categories were identified [11, 36, 37]: (1) insurance coverage or eligibility to receive service, (2) cultural issues, (3) language or communication issues, (4) organization of services and quality of care, (5) geographic access, (6) economic burden or costs of services, (7) education and health literacy, (8) social networks and support, and (9) patient-provider relationship [38–40]. Finally, we classified each study according to the type of strategies included to provide those services as: (a) health promotion strategy (HP); or (b) primary (PP), (c) secondary (SP) or (d) tertiary (TP) prevention strategy; following the model of stages of prevention [41]. (see “Box 4”). We also used the WHO-CSDH framework of actions on social determinants of health [42], to assess the potential of each model in tackling health inequities.

Results

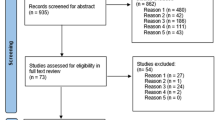

We identified 1008 citations from the databases and 377 from the manual searches. (see Fig. 1) Out of the 39 studies selected in the review, 17 were categorized as PMC and 22 as PHC. A summary of selected studies is presented in Table 1, and Online Appendix 4.

A total of 22 studies (56%) were theoretical or discussion papers and policy or program reports, 15 were empirical studies (7 quantitative, 8 qualitative) and 2 were reviews. 14 studies targeted immigrant populations in general, including refugees; 24 studies focused on specific immigrant groups (Hispanic, Chinese, etc.) and one focused only on refugees. The immigrants groups more represented were Hispanic/Latinos (8) and Asians (Chinese and Koreans) (6). Three studies were dedicated to immigrant women and three to children. The majority of the studies (62%) were conducted in North-America with 24 studies (21 in the US and 3 in Canada); followed by Europe (6), Australia (2) and other countries (2). Only one study from a former low-middle income country was identified (Chile). Five studies involved several countries.

Both health care models have similar distribution on the type of health care problems or service provided. More than 60% of the type of services for both PMC and PHC were classified as primary care measures, including general medical care for acute or chronic conditions, prenatal care, immunization, disease screening, emergency care and other services (Table 2). Provision of preventive services, were reported in about 40% of the studies in both models, using preventive strategies for specific health problems, such as oral health [43], CVD [44], cancer screening [45, 46]; or preventive care for specific subgroups like children [47], or perinatal care [48, 49]. Mental health services (general mental care, or care for specific mental disorders such as depression) were provided in less than 20% of studies (three studies in each model) [50–55].

Targeting Barriers to Primary Health Care for Immigrant Populations

For PHC models, the main barriers addressed were those related to socio-cultural issues, as nearly all of those studies (20 out of 22) included strategies to tackle social barriers, such as attention to cultural norms and to religious background, [52, 56–59] the utilization of safety net models [60] and the use of interpreters and cultural brokers [61] (Table 3). Seventeen studies described strategies promoting social networks and support (78%), such as the involvement of ethno-cultural community leaders and organizations, [52, 57, 62] as well as implementing other social programs and services that helped immigrants with their integration [54, 59, 63, 64]. Strategies to address barriers concerning language and communication problems were reported by 14 studies, including the use of language services [52, 57], and a similar number described strategies for organizing services and quality of care issues (e.g. laboratory services, emergency care), as well as those that promote education and improvement of health literacy [65–67].

Among the PMC models, the top strategy was the organization of services and quality of care (71%), such as multidisciplinary and coordination of care [44, 60], integration of services [68], collaborative model of care [55], medical home model [69]. This was followed by strategies to address cultural barriers (53%) (language, health beliefs) patient-provider relationship (41%) [46, 50, 70], plans to improve access to insurance and entitlement to care (six studies) [44, 71, 72]; as well as tactics to tackle economic costs associated with care (five studies) [43, 73]. (Table 3).

Implementing Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Strategies

All of the PHC studies included strategies of health promotion and social determinants, compared to only 71% of the PMC studies. Examples of those strategies were interventions to improve general education levels of the targeted population [52, 63, 74, 75], or their health literacy [65, 66, 76, 77]; as well as wide health promotion programs using community health workers [44, 57–59, 67]. With regard to primary prevention, all the PHC models encompassed typical primary prevention strategies, such as immunization, disease screening, perinatal care, [74] among others (Table 3). In contrast, only 88% of the PMC models employed primary prevention strategies as part of their bundle package of services; and were more consistent providing tertiary prevention strategies.

Discussion

Overall, the organization of primary healthcare in most countries consists of the provision of health and medical services to the general population, usually in health care facilities (public or private), mainly delivered by health care professionals (doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, dieticians, etc.). According to the emphasis of those services, the system can be mainly medical or curative-based, which corresponds to the PMC model; or can be more community-oriented, focusing on strategies outside the health care services, supported by or engaging other social services, which corresponds to a PHC model. In the actual healthcare practice of many countries, both approaches can coexist and an overlapping of strategies can be seen, but in many cases, specific projects or programs can be identified with a PMC or a PHC model.

Our findings reveal that the organization of services or strategies to deliver health care to immigrant populations at the entrance of the health system can be either through a PMC or a PHC model. Both models can address immigrant population health needs, but they differ in the scope of their strategies and the potential impact on immigrants’ health transitions.

Addressing Barriers to Care

Regarding strategies to address barriers to care, PHC models were more consistent than those of PMC in developing strategies to challenge cultural barriers, such as language and communication difficulties, and in providing social support, and educational programs, [52, 56–59] while only half of the PMC models addressed those common newly arriving immigrant barriers [40, 78, 79].

The studies using the PMC model, however, were more consistent than PHC in implementing strategies to improve the organization and quality of clinical medical care and patient-provider relationships. This has been the focus of many primary care reforms [80, 81]. Some PMC models also integrated strategies to address cultural barriers, including measures to improve language and communication, which can make these services more migrant-friendly and culturally appropriate [19, 82].

Focusing on Health Promotion

Regarding the application of preventive interventions, all studies using the PHC model included health promotion and primary prevention strategies as part of their organization and delivery of services, while among the PMC models around 80% included those types of interventions. Consistent with the barriers addressed, the PHC models were also more consistent in implementing health promotion strategies through culturally-oriented health care interventions and educational programs, promoting and fostering social support, as well as developing community networks in organizing primary care to immigrant populations.

Potential to Impact on Health Care Inequities

Using the WHO-CSDH framework of actions on social determinants of health [42], we identified that PHC models were better able to implement strategies to address contextual factors (i.e. socioeconomic and political context) and structural mechanisms (e.g. social position, education, income, occupation, ethno-cultural factors); that may contribute in reducing immigrants health inequities. For example, the PHC models more frequently implemented strategies to address and accommodate cultural and social values through comprehensive experiences of social and community health services for immigrants,[52, 54, 57–59, 66, 69] as well as education and health literacy programs, than the PMC models [65, 67, 74]. Those structural factors have also been reinforced by international organizations and global consultations on migrants’ health and health care as part of migrant-sensitive health care systems [83, 84].

The PHC models were also better able to roll out strategies to alter key intermediary factors such as material circumstances (housing, financial capacity for consumption) that can have a meaningful influence on how immigrants deal with the new environment as well as psychosocial circumstances that can act as significant stressors during their settlement process. Also, some health programs based on PHC models have developed strategies of social participation and established partnerships with organizations outside the health sector, such as legal services, food distribution and transportation [63, 69]. Experiences of community health centers (CHC) have also provided evidence on the value of intersectoral collaboration to improve health outcomes [57, 58]. Research in Canada and United States has acknowledged that CHCs are serving disadvantaged populations, including a great number of immigrants [87, 88]. For example, a large proportion of immigrants and refugees in urban areas of Ontario are receiving healthcare from CHCs [89, 90]. A recent study in China evaluating CHC models in China, revealed the value of community-based primary care models to improve access, comprehensiveness, and quality of care [91].

Another intermediary factor shaping the health of the population and a potential contributor in reducing health inequities is social capital [92, 93]. Research in the last three decades has explored the influence of social factors and social networks on the health status of individuals and populations [94, 95]. Furthermore some studies also support the importance of social capital in the integration of immigrants into the new society [96]. In line with that, key strategies offered by the PHC models to strengthen social networks and social cohesion to help immigrant families in dealing with integration challenges included access to health services [67, 69, 75, 76, 97]. Finally, another key feature of PHC models is the involvement of community health workers (CHW) or health promoters, [58, 60, 67, 75] who have an essential role as an educator, a health broker, and also as a connector between the community and the health services.

Inequities in health can only be partially tackled by addressing and improving health care, but appropriate health services can have an impact on people’s health status, not only for migrants but also for the population in general [97, 98]. This review reveals that both models have strengths and limitations in providing health care to immigrant populations. Although a mix of strategies from both types of models can be seen in some contexts, the PMC models applied more strategies to enhance the quality of medical services, where the PHC models were more persistent in including strategies to address social and cultural needs of immigrant populations. These results seem to be consistent with growing evidence indicating that health systems grounded on the PHC principles can be effective in tackling health inequities by acting upon the social determinants of health [99–101].

Strengths and Limitations

To the best of our knowledge, no previous research has compared these two models on their capacities to respond to immigrants’ health care needs, neither examined their strategies to address the barriers of access to primary care services nor assessed their potential to tackle health inequities.

However, the analysis has some limitations. None of the studies reported the effectiveness of their interventions or measured the impact on inequities in health care to immigrant populations. Also, these results were limited to the search terms “model of care”, “primary care”, and “primary health care”, which may not have identified all models or bundles of primary care services to. In addition, as these two models can coexist, an overlapping in the use of these services by immigrants can also occur, since health care systems are more and more applying a blend of strategies and interventions to enhance the quality of health care. Finally, we restricted the review to literature published in English.

Conclusions

This systematic scoping review shows that immigrant populations receive a variety of primary health care services in the host country. These services come from a mix of PMC or a PHC approaches. Both models can be helpful in responding to immigrants’ health needs. However, the PHC model was more consistent in applying strategies to address critical factors that affect immigrants in their settlement process. Hence PHC models may be better suited to address social determinants of health and might have more potential capacities to reduce health inequities among immigrants. Despite the differences identified in this study, the two models could act synergistically in responding to immigrants’ healthcare needs. Further research is needed to assess the actual impact and interaction of these models on immigrant health inequities.

References

Pottie K, Greenaway C, Feightner J, et al. Evidence-based clinical guidelines for immigrants and refugees. CMAJ. 2011;183(12):E824–925.

McDonald J, Kennedy S. Insights into the ‘healthy immigrant effect’: health status and health service use of immigrants to Canada. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(8):1613–27.

Hyman I, Jackson B. The healthy immigrant effect: a temporary phenomenon? Health Policy Res Bull. 2010;17:17–21.

Fuller-Thomson E, Noack AM, George U. Health decline among recent immigrants to Canada: findings from a nationally-representative longitudinal survey. Can J Public Health. 2011;102(4):273–80.

Gee EM, Kobayashi KM, Prus SG. Examining the healthy immigrant effect in mid- to later life: findings from the Canadian Community Health Survey. Can J Aging. 2004;23(Suppl 1):S61–9.

Choi SH. Testing healthy immigrant effects among late life immigrants in the United States: using multiple indicators. J Aging Health. 2012;24(3):475–506.

Stanciole AE, Huber M. Access to health care for migrants, ethnic minorities, and asylum seekers in Europe. Vienna: European Centre for Social Welfare Policy and Research; 2009.

Joshi C, Russell G, Cheng I-H, et al. A narrative synthesis of the impact of primary health care delivery models for refugees in resettlement countries on access, quality and coordination. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12(1):88.

Whitehead M. The concepts and principles of equity and health. Copenhagen: World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe; 1990.

Tugwell P, Robinson V, Morris E. Mapping global health inequalities: challenges and opportunities. Santa Cruz: Center for Global, International and Regional Studies, UC Santa Cruz; 2007.

Lebrun LA, Dubay LC. Access to primary and preventive care among foreign-born adults in Canada and the United States. Health Serv Res. 2010;45(6 Pt 1):1693–719.

Derose KP, Bahney BW, Lurie N, Escarce JJ. Review: immigrants and health care access, quality, and cost. Med Care Res Rev. 2009;66(4):355–408.

Pottie K, Ng E, Spitzer D, Mohammed A, Glazier R. Language proficiency, gender and self-reported health: an analysis of the first two waves of the longitudinal survey of immigrants to Canada. Can J Public Health. 2008;99(6):505–10.

Tudor Hart J. The inverse care law. Lancet. 1971;297(7696):405–12.

Simich L. Health literacy and immigrant populations. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada and Metropolis Canada; 2009.

Pottie K, Dahal G, Georgiades K, Premji K, Hassan G. Do first generation immigrant adolescents face higher rates of bullying, violence and suicidal behaviours than do third generation and native born? J Immigr Minor Health. 2015;17(5):1557–66. doi:10.1007/s10903-014-0108-6.

Clough J, Lee S, Chae DH. Barriers to health care among Asian immigrants in the United States: a traditional review. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24(1):384–403.

Chauvin P, Simonnot N. Access to health care for vulnerable groups in the European Union in 2012. Médecins du monde; 2012.

Harris MF. Access to preventive care by immigrant populations. BMC Med. 2012;10:55.

Muldoon LK, Hogg WE, Levitt M. Primary care (PC) and primary health care (PHC): what is the difference? Can J Public Health. 2006;97(5):409–11.

Egwu IN. Primary is not the same as primary health care, or is it? Fam Community Health. 1984;7(3):83–8.

Awofeso N. What is the difference between “primary care” and “primary healthcare”? Qual Prim Care. 2004;12:93–4.

Barnes D, Eribes C, Juarbe T, et al. Primary health care and primary care: a confusion of philosophies. Nurs Outlook. 1995;43(1):7–16.

WHO. Primary health care: now more than ever. The world health report 2008. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008.

Meads G. Primary health care models: learning across continents. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2006;7(04):281–3.

Lamarche PA, Beaulieu M-D, Pineault R, Contandriopoulos A-P, Denis J-L, Haggerty J. Choices for change: the path for restructuring primary healthcare services in Canada. Ottawa: Canadian Health Services Research Foundation; 2003.

Haggerty J, Burge F, Lévesque J-F, et al. Operational definitions of attributes of primary health care: consensus among Canadian experts. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5(4):336–44.

Samaan Z, Mbuagbaw L, Kosa D, et al. A systematic scoping review of adherence to reporting guidelines in health care literature. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2013;6:169–88.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

iCAHE. Critical appraisal tools. Critical appraisal skills programme (CASP). http://w3.unisa.edu.au/cahe/Resources/CALibrary/default.asp.

NCCMT. Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies. 1998. http://www.nccmt.ca/registry/view/eng/14.html. Accessed 2 Aug 2013.

Tugwell P, Petticrew M, Kristjansson E, et al. Assessing equity in systematic reviews: realising the recommendations of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. BMJ. 2010;341:873–7.

Ciliska D, Thomas H, Buffett C. An introduction to evidence-informed public health and a compendium of critical appraisal tools for public health practice. Hamilton: McMaster University; 2010.

Kmet LM, Lee RC, Cook LS. Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. Edmonton: Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research; 2004.

Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13(1):1–8.

Scheppers E, van Dongen E, Dekker J, Geertzen J, Dekker J. Potential barriers to the use of health services among ethnic minorities: a review. Fam Pract. 2006;23(3):325–48.

Pitkin Derose K, Bahney BW, Lurie N, Escarce JJ. Review: immigrants and health care access, quality, and cost. Med Care Res Rev. 2009;66(4):355–408.

Derose KP, Escarce JJ, Lurie N. Immigrants and health care: sources of vulnerability. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26(5):1258–68.

Access Alliance. Racialized groups and health status: a literature review exploring poverty, housing, race-based discrimination and access to health care as determinants of health for racialized groups. Access Alliance Multicultural Health and Community Services; 2005.

McKeary M, Newbold B. Barriers to Care: The challenges for canadian refugees and their health care providers. J Refugee Stud. 2010;23(4):523–45.

AFMC. Basic concepts in prevention, surveillance, and health promotion: the stages of prevention. In: Donovan D, McDowell I, Hunter D, editors. AFMC primer on population health: the association of faculties of medicine of canada public health educators’ network; 2010.

Solar O, Irwin A. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

Telleen S, Rhee Kim YO, Chavez N, Barrett RE, Hall W, Gajendra S. Access to oral health services for urban low-income Latino children: social ecological influences. J Public Health Dent. 2012;72(1):8–18.

Singh-Franco D, Perez A, Wolowich WR. Improvement in surrogate endpoints by a multidisciplinary team in a mobile clinic serving a low-income, immigrant minority population in South Florida. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24(1):67–77.

Aragones A, Schwartz MD, Shah NR, Gany FM. A randomized controlled trial of a multilevel intervention to increase colorectal cancer screening among Latinos immigrants in a primary care facility. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(6):564–7.

Taylor VM, Yasui Y, Nguyen TT, et al. Pap smear receipt among Vietnamese immigrants: the importance of health care factors. Ethn Health. 2009;14(6):575–89.

Belue R, Degboe AN, Miranda PY, Francis LA. Do medical homes reduce disparities in receipt of preventive services between children living in immigrant and non-immigrant families? J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14(4):617–25.

De Jonge A, Rijnders M, Agyemang C, et al. Limited midwifery care for undocumented women in the Netherlands. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2011;32(4):182–8.

Guruge S, Hunter J, Barker K, McNally MJ, Magalhaes L. Immigrant women’s experiences of receiving care in a mobile health clinic. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(2):350–9.

Baarnhielm S, Ekblad S. Turkish migrant women encountering health care in Stockholm: a qualitative study of somatization and illness meaning. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2000;24(4):431–52.

Jensen NK, Norredam M, Priebe S, Krasnik A. How do general practitioners experience providing care to refugees with mental health problems? a qualitative study from Denmark. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:17.

Kim MJ, Cho HI, Cheon-Klessig YS, Gerace LM, Camilleri DD. Primary health care for Korean immigrants: sustaining a culturally sensitive model. Public Health Nursing (Boston Mass). 2002;19(3):191–200.

Kirmayer LJ, Narasiah L, Munoz M, et al. Common mental health problems in immigrants and refugees: general approach in primary care. CMAJ. 2011;183(12):E959–67.

Kaltman S, Pauk J, Alter CL. Meeting the mental health needs of low-income immigrants in primary care: a community adaptation of an evidence-based model. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2011;81(4):543–51.

Kwong K, Chung H, Cheal K, Chou J, Chen T. Depression care management for Chinese Americans in primary care: a feasibility pilot study. Community Ment Health J. 2013;49(2):157–65.

Ahmed SM, Lemkau JP. Cultural issues in the primary care of South Asians. J Immigr Health. 2000;2(2):89–96.

Fowler N. Providing primary health care to immigrants and refugees: the North Hamilton experience. CMAJ. 1998;159(4):388–91.

Frank AL, Liebman AK, Ryder B, Weir M, Arcury TA. Health care access and health care workforce for immigrant workers in the agriculture, forestry, and fisheries sector in the southeastern US. Am J Ind Med. 2013;56(8):960–74.

Morrison SD, Haldeman L, Sudha S, Gruber KJ, Bailey R. Cultural adaptation resources for nutrition and health in new immigrants in central North Carolina. J Immigr Minor Health. 2007;9(3):205–12.

Blewett LA, Casey M, Call KT. Improving access to primary care for a growing Latino population: the role of safety net providers in the rural Midwest. J Rural Health. 2004;20(3):237–45.

Isaacs S, Valaitis R, Newbold KB, Black M, Sargeant J. Brokering for the primary healthcare needs of recent immigrant families in Atlantic, Canada. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2013;14(1):63–79.

Chin JJ, Kang E, Kim JH, Martinez J, Eckholdt H. Serving Asians and Pacific Islanders with HIV/AIDS: challenges and lessons learned. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2006;17(4):910–27.

Abreu M, Hynes P. The Latino Health Insurance Program: a pilot intervention for enrolling latino families in health insurance programs, East Boston, Massachusetts, 2006–2007. Prev Chronic Dis. 2009;6(4):A129.

Isralowitz RE. Vision change and quality of life among Ethiopian elderly immigrants in Israel. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2000;33(1):89–96.

De Jesus Diaz-Perez M, Farley T, Cabanis CM. A program to improve access to health care among Mexican immigrants in rural Colorado. J Rural Health. 2004;20(3):258–64.

Levin-Zamir D, Keret S, Yaakovson O, et al. Refuah shlema: a cross-cultural programme for promoting communication and health among ethiopian immigrants in the primary health care setting in Israel evidence and lessons learned from over a decade of implementation. Global Health Promot. 2011;18(1):51–4.

Ramos RL, Hernandez A, Ferreira-Pinto JB, Ortiz M, Somerville GG. Promovision: designing a capacity-building program to strengthen and expand the role of promotores in HIV prevention. Health Promot Pract. 2006;7(4):444–9.

Gould G, Viney K, Greenwood M, Kramer J, Corben P. A multidisciplinary primary healthcare clinic for newly arrived humanitarian entrants in regional NSW: model of service delivery and summary of preliminary findings. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2010;34(3):326–9.

Carrillo JE, Shekhani NS, Deland EL, et al. A regional health collaborative formed By NewYork-Presbyterian aims to improve the health of a largely Hispanic community. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(10):1955–64.

Lofvander M, Dyhr L. Transcultural general practice in Scandinavia. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2002;20(1):6–9.

Ku L. Improving health insurance and access to care for children in immigrant families. Ambul Pediatr. 2007;7(6):412–20.

WHO. International migration, health and human rights. Geneva: WHO; 2003.

Tapp H, Smith HA, Dixon JT, Ludden T, Dulin M. Evaluating primary care delivery systems for an uninsured hispanic immigrant population. Fam Community Health. 2013;36(1):19–33.

Lyberg A, Viken B, Haruna M, Severinsson E. Diversity and challenges in the management of maternity care for migrant women. J Nurs Manag. 2012;20(2):287–95.

McElmurry BJ, Park CG, Buseh AG. The nurse-community health advocate team for urban immigrant primary health care. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2003;35(3):275–81.

Priebe S, Sandhu S, Dias S, et al. Good practice in health care for migrants: views and experiences of care professionals in 16 European countries. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:187.

Sim S-C, Peng C. Lessons learned from a program to sustain health coverage after September 11 in New York City’s Chinatown. New York: Asian American Federation of New York; 2004.

Marques TV. Refugees and migrants struggle to obtain health care in Europe. CMAJ. 2012;184(10):E531–2.

Muggah E, Dahrouge S, Hogg W. Access to primary health care for immigrants: results of a patient survey conducted in 137 primary care practices in Ontario, Canada. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13(1):128–34.

Comino E, Davies G, Krastev Y, et al. A systematic review of interventions to enhance access to best practice primary health care for chronic disease management, prevention and episodic care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(1):415.

Baker R, Willars J, McNicol S, Dixon-Woods M, McKee L. Primary care quality and safety systems in the English National Health Service: a case study of a new type of primary care provider. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2014;19(1):34–41.

Pottie K, Hadi A, Chen J, Welch V, Hawthorne K. Realist review to understand the efficacy of culturally appropriate diabetes education programmes. Diabet Med. 2013;30(9):1017–25.

IOM. Migration initiatives 2013 in support of development. Geneva: International Organization for Migration; 2013.

WHO. Health of migrants: the way forward. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

Cabieses B, Tunstall H, Pickett KE, Gideon J. Understanding differences in access and use of healthcare between international immigrants to Chile and the Chilean-born: a repeated cross-sectional population based study in Chile. Int J Equity Health. 2012;11(68):16.

Han G-S, Davies C. Ethnicity, Health and Medical Care: Towards a critical realist analysis of general practice in the Korean community in Sydney. Ethn Health. 2006;11:409–30.

Kantayya VS, Lidvall SJ. Community health centers: disparities in health care in the United States 2010. Dis Mon. 2010;56(12):681–97.

Nerad S, Janczur A. Primary health care with immigrant and refugee populations. Issues and challenges. Aust J Prim Health. 2000;6(4):222–9.

Shah CP, Moloughney BW. A strategic review of the community health centre program. Ontario: Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; 2001.

Glazier RH, Zagorski BM, Rayner J. Comparison of primary care models in Ontario by demographics, case mix and emergency department use, 2008/09 to 2009/10. Toronto: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2012.

Shi L, Lee D-C, Liang H, et al. Community health centers and primary care access and quality for chronically-ill patients—a case-comparison study of urban Guangdong Province, China. Int J Equity Health. 2015;14(1):90.

Kawachi I, Kennedy BP, Lochner K, Prothrow-Stith D. Social capital, income inequality, and mortality. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(9):1491–8.

Gilbert J, van Kemenade S. Social capital and health: maximizing the benefits. In: Gilbert J, van Kemenade S, editors. Applied research and analysis directorate HPB, trans. Health policy research bulletin, vol 12. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2006.

Gilbert KL, Quinn SC, Goodman RM, Butler J, Wallace J. A meta-analysis of social capital and health: a case for needed research. J Health Psychol. 2013;18(11):1385–99.

Bouchard L, Roy JF, Van Kemenade S. Research traditions: an overview. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2006.

van Kemenade S, Roy JF, Bouchard L. Social networks and vulnerable populations: findings from the GSS. In: Gilbert J, van Kemenade S, editors. Health policy research bulletin. Vol social capital and health: maximizing the benefits. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2006. pp. 16–20.

WHO Europe. How health systems can address health inequities linked to migration and ethnicity. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2010.

WHO-CSDH. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final report of the commission on social determinants of health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008.

Rasanathan K, Montesinos EV, Matheson D, Etienne C, Evans T. Primary health care and the social determinants of health: essential and complementary approaches for reducing inequities in health. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65(8):656–60.

Ramírez NA, Ruiz JP, Romero RV, Labonté R. Comprehensive primary health care in South America: contexts, achievements and policy implications. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 2011;27:1875–90.

Labonté R, Sanders D, Packer C, Schaay N. Is the Alma Ata vision of comprehensive primary health care viable? Findings from an international project. Global Health Action. 2014;7:16.

IOM. Glossary on migration. Geneva: International Organization for Migration; 2004.

WHO. A glossary of terms for community health care and services for older persons. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004.

WHO-UNICEF. Declaration of Alma-Ata. International conference on primary health care, Sept 6–12, 1978, Alma-Ata, USSR.

Muldoon L, Dahrouge S, Hogg W, Geneau R, Russell G, Shortt M. Community orientation in primary care practices: results from the comparison of models of primary health care in Ontario study. Can Fam Physician. 2010;56:676–83.

Longlett SK, Kruse JE, Wesley RM. Community-oriented primary care: historical perspective. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2001;14(1):54–63.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Batista, R., Pottie, K., Bouchard, L. et al. Primary Health Care Models Addressing Health Equity for Immigrants: A Systematic Scoping Review. J Immigrant Minority Health 20, 214–230 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-016-0531-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-016-0531-y