Abstract

Little is known about Black–White health inequalities in Canada or the applicability of competing explanations for them. To address this gap, we used nine cycles of the Canadian Community Health Survey to analyze multiple health outcomes in a sample of 3,127 Black women, 309,720 White women, 2,529 Black men and 250,511 White men. Adjusting for age, marital status, urban/rural residence and immigrant status, Black women and men were more likely than their White counterparts to report diabetes and hypertension, Black women were less likely than White women to report cancer and fair/poor mental health and Black men were less likely than White men to report heart disease. These health inequalities persisted after controlling for education, household income, smoking, physical activity and body-mass index. We conclude that high rates of diabetes and hypertension among Black Canadians may stem from experiences of racism in everyday life, low rates of heart disease and cancer among Black Canadians may reflect survival bias and low rates of fair/poor mental health among Black Canadian women represent a mental health paradox similar to the one that exists for African Americans in the United States.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A substantial body of research has examined Black–White health inequalities in the United States, overwhelmingly indicating that African Americans typically suffer poorer health than White Americans. Surprisingly little is known, however, about Black–White health inequalities in neighboring Canada. A lack of attention to racial health inequalities in Canada may reflect a national rhetoric of multiculturalism and tolerance that precludes an explicit focus on ‘race’ in favor of issues associated with acculturation and immigration; the comparably vast literature on the health consequences of immigration to Canada [1, 2] is testament to this possibility. In addition, Canada’s comparatively small population (approximately 35 million) and small proportion of residents who identity as Black (2.9 % in the 2011 Canadian Census) have made it difficult for health researchers to assemble reasonably large, nationally representative samples of Black Canadians. We address this gap in the health inequalities literature by investigating Black–White health inequalities in Canada, and potential explanations for them, using nationally representative data. Combining data from all nine cycles of the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) enables us to investigate Black–White disparities in a wide range of health outcomes. We examine disparities in the occurrence of prominent illnesses that can affect quality of life and longevity, namely, low self-rated health, low self-rated mental health, diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, cancer and asthma.

Many lines of explanation have been applied to Black–White health inequalities in the United States. These include the residential segregation of African Americans, differences in socioeconomic status, differential access to quality health care, the internalization by African Americans of the overall society’s negative characterizations of them, sedentary lifestyles and obesity, and the psychosocial stress resulting from experiences of interpersonal racism and discrimination [3–5]. Although Canada does not possess the same legacy of racial segregation and has universally funded health care, anti-Black racism does exist in Canadian society [6]. Explanations for Black–White health inequalities pertaining to socioeconomic status, internalization of stereotypes, lifestyles and racial discrimination are all eminently plausible in this context. The CCHS allows us to examine the utility of socioeconomic status (education and household income), health behaviors (smoking and physical activity) and body-mass index in particular for explicating Canadian Black–White health inequalities.

Methods

The CCHS is a cross-sectional survey that collects information related to health status, health care utilization and health determinants for the Canadian population. Statistics Canada conducted the CCHS in 2001, 2003 and 2005 and annually from 2007. The target populations for these cross-sectional surveys were all persons 12 years of age and older residing in Canada, excluding individuals living on Indian Reserves and on Crown Lands, institutional residents, full-time members of the Canadian Armed Forces and residents of some remote regions. One person was chosen randomly from each household to complete the survey. Response rates for the surveys range from a high of 84.7 % in 2001 to a low of 67.0 % in 2012.

Race was assessed by asking whether respondents regard themselves as White, Black, some other identity or some combination of identities. We confined our analyses to those survey participants who reported White or Black only. Immigration status distinguishes respondents born in Canada from recent immigrants (immigrated to Canada less than 10 years ago), midterm immigrants (10–19 years ago) and long-term immigrants (20 or more years ago). Marital status distinguishes between married or common-law, divorced or separated, widowed and never married. Educational attainment distinguishes between less than a high school diploma, high school diploma or G.E.D., community college or trade school, and bachelor’s degree or higher. Household income, expressed in population deciles, depicts each respondent’s household income relative to a low-income cut-off that accounts for household size and the population size of the respondent’s community of residence. Smoking status distinguishes between never smoked, formerly smoked, smokes occasionally and smokes daily. A physical activity index characterizes overall activity levels as active, moderately active or inactive based on a set of questions asking about different leisure activities. Body-mass index (BMI) is calculated from self-reported height and weight. Self-rated health and self-rated mental health are both dichotomized to distinguish ‘fair’ or ‘poor’ from ‘excellent’, ‘very good’ or ‘good’. Other indicators assess the presence of diabetes, hypertension, asthma, heart disease and cancer. For the latter, responses confirming either current or previous experience with cancer are included in the affirmative.

We combined data from all cycles of the CCHS that occurred between 2001 and 2012. Excluding cases without valid information for race or immigrant status produced a sample of 3,127 Black women, 309,720 White women, 2,529 Black men and 250,511 White men aged 25 and older. Socio-demographic and health-related characteristics of the un-weighted sample are described in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Table 1 indicates that the White women and men were almost ten years older, on average, than the Black women and men. Proportionately more Black respondents than White respondents were unmarried and lived in urban settings. Almost nine in ten White respondents but fewer than two in ten Black respondents were born in Canada. These differences speak to the importance of controlling for linear and nonlinear effects of age as well as immigrant status and other socio-demographic factors in models predicting ill health.

Tables 1 and 2 identify missing data for the independent and dependent variables. BMI was not calculated for pregnant women and the self-rated mental health question was not asked in 2001. To accommodate missing values in our regression models, we adopted the imputed data for household income provided by Statistics Canada for the 2005–2012 cycles, utilized missing-data categories for household income in 2001 and 2003 and for the other independent variables, and applied list-wise deletion to the dependent variables. To account for the complex sampling design, we applied the master weight and 500 bootstrap replicate weights provided by Statistics Canada to our models, a strategy recommended by Statistics Canada to produce more accurate estimates of effect size and statistical significance, respectively. All statistical analyses were conducted in Stata 12. The study was approved by the Behavioural Research Board at the University of British Columbia.

Results

For each dependent variable, separately for women and for men, we produced three binary logistic regression models. The first model in each series controlled for survey year, age in years, square of age, marital status, rural versus urban residence and immigrant status. The second model additionally controlled for education and household income. The third model additionally controlled for smoking, physical activity and BMI. These models are summarized in Table 3.

Women

Controlling for demographic characteristics in the first model shown in Table 3, Black women were more likely than White women to report diabetes (OR 2.74, 95 % CI 2.06–3.64) and hypertension (OR 2.52, 95 % CI 2.07–3.06) and less likely to report cancer (OR 0.42, 95 % CI 0.28–0.61). We found no statistically significant differences between Black and White women in the likelihoods of fair/poor health, fair/poor mental health, heart disease and asthma. Controlling for socioeconomic status, health behaviors and BMI did little to alter these associations except that Black women became significantly less likely than White women to report fair/poor mental health (OR 0.63, 95 % CI 0.46–0.86) in the full model.

Men

Controlling for demographic characteristics, Black men were more likely than White men to report diabetes (OR 1.95, 95 % CI 1.53–2.48) and hypertension (OR 1.41, 95 % CI 1.17–1.71) and less likely to report heart disease (OR 0.60, 95 % CI 0.40–0.89). We found no statistically significant differences between Black and White men in the likelihoods of fair/poor self-rated health, fair/poor mental health, asthma and cancer. Controlling for socioeconomic status, health behaviors and BMI did little to alter these associations.

Discussion

Our study contributes to a small but growing literature on Black–White health inequalities in Canada. Consistent with previous research [7] we found no significant differences between Black and White Canadians in regards to asthma or self-rated health. We also found that Black Canadians were less likely than White Canadians to report heart disease (among men) and cancer (among women). Black women were less likely than White women to report fair/poor mental health, a result that stands in contrast with another study [8] that reported no such difference. Also consistent with previous research [8–11] we found that Black Canadians were significantly more likely than White Canadians to report diabetes (with odds ratios of 2.74 among women and 1.95 among men) and hypertension (with odds ratios of 2.52 among women and 1.41 among men). Our proposed mediators—household income, educational attainment, smoking, frequency of physical activity and BMI—failed to explain the abovementioned health inequalities.

Comparison with Black–White health inequalities in the United States is instructive. First, American Black–White disparities in asthma reflect a legacy of systemic discrimination that has concentrated African Americans in poor neighborhoods rife with pollution, waste disposal, poor housing and other sources of airborne toxins [3, 5, 12, 13]. The fact that residential segregation is much less pronounced in Canada than in the United States [14], which means that Black Canadians are comparably less likely than Black Americans to live in poor neighborhoods, may explain why we do not identify Black–White inequalities in asthma prevalence in Canada.

Second, the American Heart Association reports that among African Americans, the rate of heart disease is relatively low but the rate of hypertension is relatively high [15]. This paradox manifests itself in our study. However, according to the American Heart Association, mortality rates from cardiovascular disease are also higher for African Americans than for White Americans. This suggests that hypertension is not only more prevalent among African Americans but also more lethal and that fewer African Americans survive to report heart disease in surveys. Similarly, self-reported cancer incidence is lower among African Americans than White Americans [16] but mortality from cancer is higher [17] which implies that cancer too is more lethal for African Americans and/or tends to be diagnosed later. It seems reasonable to think that survival bias similarly explains at least some of the relatively low rates of self-reported heart disease and cancer among Black Canadians.

Third, as is the case in our study, the American literature documents a race paradox in mental health wherein African Americans typically report better mental health than White Americans [18], a difference that social factors such as family cohesion cannot fully explain [19]. Research shows that some African Americans develop positive coping strategies for dealing with everyday racism and accordingly enjoy a level of physical health that is on par with White Americans [4, 20]. Other African Americans either accept or internalize negative attitudes towards Black people and correspondingly suffer poorer cardiovascular health. Factors such as these may explain the comparably high levels of self-rated mental health reported by the Black Canadian women of our study. We do not know why the race paradox in mental health does not extend to Black Canadian men.

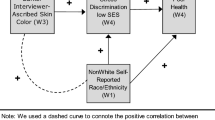

Finally, some research indicates that race-based discrimination, a lifelong stressor, contributes to the development of hypertension among African Americans [21, 22]. Other studies link chronic stress [23, 24] and internalized racism towards African Americans [25, 26] to insulin resistance and other precursors to Type 2 diabetes. Our finding that Black Canadians experience substantially higher risks of both hypertension and diabetes than White Canadians potentially implicates everyday experiences of racism and discrimination in Black–White health inequalities.

Several important limitations of our study should be noted. First, the absence of other relevant variables precludes us from conducting a more thorough analysis. For example, a proper test of discrimination as a linking mechanism between racial identity and poor health would utilize measures of perceived discrimination, objective discrimination, acceptance of discriminatory attitudes and internalized discrimination, none of which are available in the CCHS. We are also unable to investigate mechanisms pertaining to stress and quality of health care. Second, the CCHS does not include prospective mortality data which makes it difficult for us to say definitively why, compared to their White counterparts, Black women report lower rates of cancer and Black men report lower rates of heart disease. Third, although our data include sufficient numbers of Black Canadians to examine their levels of morbidity, the failure of any mediators to emerge in our analysis may be an artifact of a sample size that was still not large enough for this purpose. In future surveys, we encourage Statistics Canada to oversample racial minorities so as to provide a larger number of respondents, include components relating to racial discrimination in their surveys more often, and prioritize the study of racial health inequalities for all minority groups, including but not limited to First Nations, Métis and Inuit peoples.

Future research in this area should consider linking CCHS data to mortality data if possible. The CCHS includes postal code information which would facilitate linkage to census data and characteristics of respondents’ neighbourhoods of residence, such as the racial and ethnic composition of neighbourhoods. Socioeconomic status could be better and more fully measured by including indicators of occupation for employed people, measures of education that account for the source of the credentials and measures of wealth instead of annual income. Finally, the fact that Black women appear to be at inordinately high risk of poor health suggests that an analysis informed by intersectionality theory [27–29] an emerging theoretical paradigm that represents a symbiosis of feminist and critical race theories, may contribute to understanding the nature of Black–White health inequalities in Canada.

In conclusion, our findings regarding Black–White health inequalities in Canada are remarkably consistent with research on Black–White health inequalities in the United States. This is an important result for a country that publicly acknowledges the health effects of racism directed towards its indigenous peoples but few others.

References

Dunn JR, Dyck I. Social determinants of health in Canada’s immigrant population: results from the National Population Health Survey. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(11):1573–93.

Newbold KB, Danforth J. Health status and Canada’s immigrant population. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(10):1981–95.

Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Gannon-Rowley T. Assessing, “neighborhood effects:” social processes and new directions in research. Annu Rev Sociol. 2002;28:443–78.

Xanthos C, Treadwell HM, Holden KM. Social determinants of health among African-American men. J Mens Health. 2007;7(1):11–9.

James C, Este D, Thomas-Bernard W, Benjamin A, Lloyd B, Turner T. Race and well-being: the lives, hopes, and activism of African Canadians. Black Point, Nova Scotia: Fernwood Publishing; 2010.

Lebrun LA, LaVeist TA. Black/White racial disparities in health: a cross-country comparison of Canada and the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(17):1591–3.

Veenstra G. Mismatched racial identities, colourism, and health in Toronto and Vancouver. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(8):1152–62.

Rosella LC, Mustard CA, Stukel TA, Corey P, Hux J, Roos L, Manuel DG. The role of ethnicity in predicting diabetes risk at the population level. Ethn Health. 2012;17(4):419–37.

Landrine H, Corral I. Separate and unequal: residential segregation and Black health inequalities. Ethn Dis. 2009;19(2):179–84.

Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Bailey C, et al. Trends in asthma prevalence, health care use, and mortality in the United States, 2001–2010. NCHS data brief, no 94. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2012.

Fong E. A comparative perspective on racial residential segregation: american and Canadian experiences. Sociol Q. 1996;37(2):199–226.

Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, Carnethon M, Dai S, De Simone G, Ferguson TB, Ford E, Furie K, Gillespie C, Go A, Greenlund K, Haase N, Hailpern S, Ho PM, Howard V, Kissela B, Kittner S, Lackland D, Lisabeth L, Marelli A, McDermott MM, Meigs J, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino M, Nichol G, Roger VL, Rosamond W, Sacco R, Sorlie P, Stafford R, Thom T, Wasserthiel-Smoller S, Wong ND, Wylie-Rosett J. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121(7):E46–215.

Blackwell DL, Lucas JW, Clarke TC. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2012. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2014;10:260.

Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(1):10–29.

Zuvekas SH, Fleishman JA. Self-rated mental health and racial/ethnic disparities in mental health service use. Med Care. 2008;46(9):915–23.

Mouzon DM. Can family relationships explain the race paradox in mental health? J Marriage Fam. 2013;75(2):470–85.

Krieger N, Sidney S. Racial discrimination and blood pressure: the CARDIA Study of Young Black and White Adults. Am J Public Health. 1996;86(10):1370–8.

Chae DH, Lincoln KD, Adler NE, Syme SL. Do experiences of racial discrimination predict cardiovascular disease among African American men? The moderating role of internalized negative racial group attitudes. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(6):1182–8.

Mays VM, Cochran SD, Barnes NW. Race, race-based discrimination, and health outcomes among African Americans. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:201–25.

Hicken MT, Lee H, Morenoff J, House JS, Williams DR. Racial/ethnic disparities in hypertension prevalence: reconsidering the role of chronic stress. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(1):117–23.

Black PH. The inflammatory response is an integral part of the stress response: implications for atherosclerosis, insulin resistance, type II diabetes and metabolic syndrome X. Brain Behav Immun. 2003;17(5):350–64.

Puustinen PJ, Koponen H, Kautiainen H, Mäntyselkä P, Vanhala M. Psychological distress predicts the development of metabolic syndrome: a prospective population-based study. Psychosom Med. 2011;73(2):158–65.

Tull ES, Chambers EC. Internalized racism is associated with glucose intolerance among Black Americans in the U.S. Virgin Islands. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(8):1498.

Chambers EC, Tull ES, Fraser HS, Mutunhu NR. The relationship of internalized racism to body fat distribution and insulin resistance among African adolescent youth. J Natl Med Assoc. 2014;96(12):1594–8.

Bowleg L. The problem with the phrase Women and Minorities: intersectionality—an important theoretical framework for public health. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:1267–73.

Veenstra G. Race, gender, class, sexuality (RGCS) and hypertension. Soc Sci Med. 2013;89:16–24.

Veenstra G. Racialized identity and health in Canada: results from a nationally representative survey. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(4):538–42.

Chiu MP, Austin DM, Manuel DG, Tu JV. Comparison of cardiovascular risk profiles among ethnic groups using population health surveys between 1996 and 2007. CMAJ. 2010;182(8):E301–10.

Hankivsky O. Health inequities in Canada: intersectional frameworks and practices. Vancouver: UBC Press; 2011.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by a grant awarded to Gerry Veenstra by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada (G-13-0002797).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Veenstra, G., Patterson, A.C. Black–White Health Inequalities in Canada. J Immigrant Minority Health 18, 51–57 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-014-0140-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-014-0140-6