Abstract

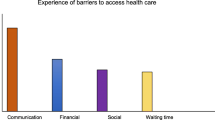

Guangzhou, one of China’s largest cities and a main trading port in South China, has attracted many African businessmen and traders migrating to the city for financial gains. Previous research has explored the cultural and economic roles of this newly emerging population; however, little is known about their health care experiences while in China. Semi-structured interviews and focus groups were used to assess health care experiences and perceived barriers to health care access among African migrants in Guangzhou, China. Overall, African migrants experienced various barriers to accessing health care and were dissatisfied with local health services. The principal barriers to care reported included affordability, legal issues, language barriers, and cultural differences. Facing multiple barriers, African migrants have limited access to care in Guangzhou. Local health settings are not accustomed to the African migrant population, suggesting that providing linguistically and culturally appropriate services may improve access to care for the migrants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

According to the International Organization for Migration, the number of international migrants worldwide increased from 76 million to 214 million between 1960 and 2010 [1, 2]. With increasing numbers of people on the move, international migrant health has become a key global public health topic [1, 3]. Subsets of international migrants are at an increased risk of morbidity and mortality because of the lack of resources to seek care early in the disease process [3]. Access to high-quality health care remains a fundamental problem for international migrants. They encounter a number of barriers, which include language difficulties [4–6], cultural differences [4, 7], economic barriers [5, 7], legal problems [8, 9], and social isolation [5, 6]. A majority of the migrant health research has been focused in Western settings; little is known about how international migrants access health services in Asian countries [10]. However, the trend of globalization in Asia is now providing opportunities for such research, enhancing our understanding of the dynamics of international migration.

In China, the number of international migrants residing in the mainland increased from 20,000 in 1980 to nearly 600,000 in 2011 [11]. The foreign population in China today is not only limited to businessmen from high-income nations, but also includes a growing number of people from low and middle-income nations, including African nations [12, 13]. China is now the leading trade partner with Africa, with a total trade volume exceeding $120 billion US dollars in 2010 [14] and a recent $20 billion US dollars loan pledge to several African nations [15]. China has become increasingly diverse as a result of the growing links with African countries. These changes are particularly apparent in the city of Guangzhou, the capital city of South China’s Guangdong Province.

Guangzhou, a key national trading hub and trading port in South China, has attracted many small-time entrepreneurs and traders from African countries migrating to the city for financial gains [12]. Since 2003, the African population has been increasing at annual rates of 30–40 percent in the city of Guangzhou [12, 13]. There are now at least 20,000 legal African residents, and an unknown number of illegal residents and short-term visitors residing in the city [13]. They are predominantly businessmen, students, and English teachers [12]. The high number of African migrants has led some Chinese to dub some areas of the city as “African Town” or “Chocolate City” [12, 16]. Previous research has explored the cultural and economic roles of this newly emerging population [12, 16, 17]; however, few studies have examined their health care experiences while in China. Thus, the aims of this study were to assess health care experiences and perceived barriers to health care access among AfricanFootnote 1 migrants in Guangzhou, Guangdong Province, China.

Theoretical/Conceptual Framework

This study is based on an integrative framework informed by the Socio-Ecological Model [18] and Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Utilization [19, 20]. The Socio-Ecological Model examines the relationship between health behaviors and interpersonal, organizational, community and policy levels [18]. This model recognizes the various levels of influence; however, it does not necessarily specify the social constructs of health care access. The Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Utilization conceives of health service access and use as a function of predisposing factors, enabling factors, and need factors. Predisposing factors refer to socio-cultural characteristics of individuals that exist prior to their illness. Enabling factors refer to the logistical aspects of obtaining care, which are the personal, family, and community resources that facilitate or hinder an individual’s ability to obtain health care. Need factors refer to the perception of need for health services, whether individual, social, or clinical. These three factors determine and influence an individual’s decisions about health service use and their satisfaction with health services [19, 20]. Integrating the two models into one conceptual framework provides a useful basis to assess barriers to health services among African migrants (Fig. 1).

Methods

With limited research on this topic and exploratory in nature, this study employed a qualitative study design to understand African migrants’ experiences of using a health service and how they perceive their access to health care in Guangzhou. Inclusion criteria for this study included individuals who were originated from an African country and 18 years of age or older. Given the high levels of linguistic diversity in African countries, English language proficiency was required because the study was carried out in English. Each participant provided verbal consent, and was offered a meal in exchange for their participation in this study. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Guangdong Provincial Centre for STI and Skin Diseases Control and the University of Hong Kong.

Participants were recruited through a convenience sampling method within local community-based organizations. Community leaders from the two largest African organizations in Guangzhou invited their members to a recruitment meeting. A total of 38 members attended the meeting and those willing to participate in the study provided contact information. Twenty-five semi-structured interviews were conducted in July 2011. In addition, two focus groups, with five males and five females each, were organized. To gain multiple perspectives on health care experiences, participants who completed the semi-structured interview were not part of the focus group. Our semi-structured interview guide was adapted from an interview guide developed by Harari et al. [5] and modified based on feedback from community leaders. The interview focused on the following questions: (1) What are your health care experiences in Guangzhou and how do you compare the experiences to those in your native country? and (2) What are the main challenges you face to accessing health care in Guangzhou? Semi-structured interviews occurred at locations preferred by the interviewees, such as restaurants or work offices, and lasted about 30–60 minutes. Focus groups followed an interview guide similar to the semi-structured interviews, and lasted approximately 50–60 minutes. All semi-structured interviews and focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

A team of five researchers was involved in the data analysis. An initial coding scheme was developed based on the integrative framework noted above. Two researchers used open coding in the multiple readings of the transcripts to identify main overarching barriers raised by participants themselves. These barriers were first coded into generalized categorical themes by levels of the integrative framework. Common sub-themes, if any, were identified within each categorical theme. All data were double coded and compared by each team member coding independently to ensure coding consistency. Team members, including the principal investigators, met biweekly to discuss coding discrepancies, review each code and definition in the codebook, and reach a consensus on new coding that needed to be identified. A total of eight main categorical and 15 sub-categorical themes were finalized by the team members (Table 1). The team coded all transcripts using MAXQDA 10 software [21].

Results

Demographic characteristics of all participants (N = 35) are summarized in Table 2. Approximately 71 percent (n = 25) were male, and 64 percent (n = 16) were married. The mean age of the participants was 33.7 years (standard deviation = 3.1). Most participants originated from Nigeria (40.6 %, n = 13) and were businessmen (86.7 %, n = 26). The mean length of stay in Guangzhou was 4.4 years (standard deviation = 7.1). Approximately 86 % (n = 30) reported English as their primary language for communication and 14 % (n = 5) reported French; 80 % (n = 28) could not speak Chinese.

Predisposing Factors

Race

Sixteen participants (45.7 %) reported experiencing forms of racial discrimination at local health services. Eight participants felt that Chinese doctors considered Chinese culture superior to African culture and Chinese patients were given priority and received preferential treatment: “The way the doctors attend to Chinese is not gonna be the way they attend to Blacks because we are foreigners. They believe Chinese first and every other person follows.” (Male, businessman, Nigeria, Interview 5) Three participants reported that Chinese doctors associated negative elements, such as drugs, illegal status and HIV, with African patients. They commented that Chinese doctors refused to touch them because they were afraid of being “infected with African diseases” and African patients were “expected” to have an HIV test even when they did not request for a testing.

Cultural Norms and Health Beliefs

Fifteen (42.9 %) participants expressed that the medical practices in China were incongruent with the health beliefs and practices in their home country. It was observed that Chinese doctors put patients on intravenous drips regardless of any diagnosed illness. Such practice was uncommon in the participants’ home country: “All the treatment that they give here is to put you on drips; everybody is almost the same way [drips] they treat them.” (Male, businessman, Togo, Interview 1) Participants also questioned the competency of Chinese doctors because the doctors appeared to be unfamiliar with common diseases in African countries: “[Chinese doctors] are not aware of some ailments like malaria that are common in Nigeria.” (Male, businessman, Togo, Interview 12).

Enabling Factors

More specific sub-themes emerged at the individual, interpersonal and organizational levels, and are discussed below.

Individual Level

Affordability Fifteen participants (42.3 %) cited that the health care costs in Guangzhou can be so high as “to put you out of business.” Participants delayed seeking health care or had to terminate medical treatments because they could not afford them. Nine participants reported that they needed to pay a deposit before getting seen by a doctor or receiving a treatment. The amount of the deposit varied, depending on circumstances, which ranged from 1,000RMB (approximately US$150) to 12,000RMB (approximately US$1,900).

Legal Status Ten participants (28.6 %) reported that not having a visa or residential permit hindered them from seeking health care due to fear of prosecution or deportation. Seven participants reported that Chinese hospitals would not treat international patients if they failed to show their passport or visa. They were also unclear whether hospitals were associated with law enforcement agencies, such as the government or immigration department: “The Chinese hospitals always want to see my passport before I see a doctor. But I never know if they want to look at the visa. Who does the nurse talk to? The police? The government? We never know these things.” (Male, businessman, Nigeria, Focus group 1).

Interpersonal Level

Language All participants reported that language barriers were the main obstacle to access health services in China. They stated that most of the doctors in Guangzhou only spoke Chinese, and they had difficulty communicating with the doctor during their medical visits: “I don’t understand what the doctors were saying because everything was in Chinese.” (Female, student, Sierra Leone, Interview 8) Seven participants were able to speak Chinese; however, their proficiency level was only sufficient for daily conversations and business communications, but not for communicating medical concerns. Their limited Chinese proficiency hindered them from understanding basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions: “I can speak and understand Chinese (…) but something more difficult and more medical and scientific, I don’t understand.” (Male, businessman, Togo, Interview 1).

Chinese Doctors’ Characteristics Twelve participants (34.3 %) expressed that Chinese doctors did not provide adequate time and information to patients, commenting that the doctors were “always in haste” and “in a rush”. The participants also felt that the doctors were inattentive and disinterested: “The doctors pretend as if they understand. When you tell them how you feel, they would say, ‘okay, okay’ just to get rid of them [the patients].” (Male, businessman, Nigeria, Interview 4) As a result, participants were left confused about the exact diagnosis and treatment after their medical consultation: “When the [test] result comes out, you don’t understand what really happened to you. Only the doctors know. And when they give you drugs, you don’t know anything about the treatment.” (Male, businessman, Nigeria, Interview 4) Five participants described the treatment in Guangzhou as a “gamble” after they went through iterative cycles of treatment, which felt like a trial-and-error process.

Ten participants (28.6 %) described that some Chinese doctors focused on generating revenues and neglected caregiving. They stated that Chinese doctors made up illnesses and pushed them to conduct unnecessary tests and treatments. For example, a Malian participant was diagnosed with cancer by a Chinese doctor during her short stay in China and was asked to pay 11,000RMB (approximately US$1,700) to undergo an operation. She could not afford the operation and returned to her own country, where a re-examination showed that the suspected area for cancer was benign. Some participants narrated anecdotes where they were offered a commission from their doctor if they introduced customers to the clinic. Participants also commented that Chinese doctors lacked empathy towards patients: “The doctors will tell you, ‘Go home and die.’ What kind of medical ethics is this?” (Male, businessman, Nigeria, Interview 14).

Privacy Four participants (11.0 %) expressed their frustration that Chinese doctors did not provide adequate privacy during consultations. They recounted that the door to the doctor’s office was left opened and other Chinese patients often interrupted the medication examination:

- Participant:

-

If I am there I must wait, but here many people coming and listening to your problem, it’s not good

- Interviewer:

-

Who were those people?

- Participant:

-

Patients. If you are with the doctor, they [other patients] come [in]to the [examination] room. They don’t want to wait outside for you to finish

(Female, housewife, Ghana, Interview 7)

One participant felt that doctors in China had little regard for patients’ medical privacy and raised concerns about confidentiality of care issues.

Organizational Level

Interpretation and Translation Sixteen participants (45.7 %) complained that Chinese hospitals and clinics did not provide professional medical interpretation services or translated medical information, such as health reports, invoices, and medication labels. Two participants reported that some doctors would use computerized translation tools to communicate with patients: “Most of the doctors use phone translation or computer translation. Sometimes the translation is not right. And what they give them there is what they’re gonna write [on the medical report].” (Male, businessman, Nigeria, Interview 5) Participants claimed that when a doctor or pharmacist issued a prescription, “everything [medication label] was in Chinese writing.” They did not know what medicine they were taking or understood the instructions. Participants also reported that there was a lack of English signage in most hospitals. As such, navigating in Chinese hospitals was a confusing affair: “Africans don’t understand the [Chinese] language (…) you just go to the hospital and follow the queue. And that’s it, wherever you end up that’s where you end up. You don’t know whether seeing a specialist here or a general doctor.” (Male, businessman, Sierra Leone, Interview 18) Additional quotes can be found in Table 3.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess health care experiences and perceived barriers to health care access among African migrants in Guangzhou, China. The primary strength of this study is the use of social theoretical frameworks for examining health care access, and the use of a qualitative study design to generate themes and gain insights into the health care experiences of African migrants. Overall, African migrants experienced various barriers to accessing health care and were dissatisfied with local health services.

In order to organize and categorize the multiple factors which may influence health service access, we applied an integrative framework informed by the Socio-Ecological Model [18] and Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Utilization [19, 20]. The main finding of our study is that a myriad of enabling factors at different levels impede access to health services among African migrants. These factors, for the most part, are consistent with the variables used in the Andersen model [19, 20]. Other factors we noted are unique to the racial and ethnic minority populations [22, 23].

In the individual level, our data indicated that affordability of medical care and legal status were an issue for health service access. African migrants reported that the high medical costs can act as a barrier, as they led them to delay seeking care. They also reported that lack of legal status can also become a barrier to health care due to fear of prosecution or deportation. These issues are commonly observed among Chinese internal migrants [24, 25]. However, unlike Chinese migrants, there are virtually no social programs in China for international migrants to mitigate their health care cost [26]. Meanwhile, the new “three illegals” policy in China on cracking down on foreigners with illegal entry, overstayed visa, and illegal employment [27], increases the vulnerability of undocumented migrants to lack of access to health services. Hence, it is reasonable to believe that African migrants face a greater difficulty in accessing care than the local migrants due to their foreigner status. In this respect, China can consider following the Europe example of the legislation of the right to health to migrants, irrespective of their status [28].

In the interpersonal level, African migrants found the Chinese doctors too hurried and not providing adequate information to the patients. They also complained that they were profit-driven and lacked the focus on caregiving, leading the African migrants to mistrust and have a negative perception toward their doctors. These negative perceptions have also been reported by the local patients [29]. The distortion of the doctor-patient relationship is commonly seen in China, and the conflict between doctors and patients was so intense that has resulted in violence incidents involving dissatisfied patients and medical staff [30, 31]. Local medical committee should pay particular attention on how to restore doctor-patient trust.

African migrants indicated that language barriers were the primary barrier to health care access. The lack of professional medical interpretation or translation services in the organizational level created an additional barrier to accessing care. Previous research has reported that language barriers are associated with less understanding of provider’s explanation and less satisfaction with health services [32]. This is commonly observed among racial and ethnic minorities seeking health services in the United States and Europe [33, 34]. Addressing language barriers is an obvious means to improve the communication between patients and providers, and thereby to increase access to health care. Professional interpreter services have been shown effective in other context [35, 36] and should be considered in South China. It is also important to note that some African migrants were from non-English speaking countries, and interpretation services in languages other than English may be warranted.

Consistent with the predisposing characteristics in the Andersen model, cultural norms and health beliefs influence perceived need and use of health services [20]. African migrants reported that Chinese doctors were unfamiliar with common diseases in African countries, which led them to be dubious about the skills of the doctors. Certain health practices, such as intravenous drips, commonly used in China are different from the mainstream culture in Western medical settings. Literature has long reported that different health beliefs and practices can act as a barrier to health services [7, 22, 37]. In this regard, Chinese doctors might require training and education to learn about patients’ culture in order to respond their varied perspectives and values about health and well-being.

This study has several important limitations. First, this study has limited generalizability to other African migrants in the area or other African communities due to the use of convenience sampling methodology. Second, the self-selection of participants in the study might impose some inherent selection bias. Third, participants with middle or high socioeconomic status were overrepresented in the sample, and therefore our findings do not covey differences in health service use according to social rank groups. Nonetheless, our sample was similar to the distribution of African migrants to China, which largely consists of businessmen [12]. Our sample also lacked the representations from migrants who are non-English speakers. Recommendations for future research include replicating the design of this study with non-English speaking migrants, since they might face even greater difficulty in accessing care in China. Lastly, this study focused on the barriers at the individual, interpersonal and organizational levels of the Socio-Ecological Model. Research assessing the community and policy level of China’s health care system might be necessary. Quantitative research on migrant’s health behaviors and outcomes, such as personal health practices, perceived health status, and evaluated health status, would also be useful to further explore the health issues among African migrants.

Conclusions

In conclusion, African migrants face a number of barriers and have limited access to health care in Guangzhou, China. These barriers can be broken down through systematic actions at the service delivery and policy-making levels. These include implementation of formal interpreter services and culturally appropriate services at local health services, and establishment of policies that ensure easy and equal access to health care for international migrants.

Notes

Our use of the term African here is meant to include all citizens of countries on the African continent, most of whom are members of the African Union, or anybody who considers themselves to be of African origins. In so doing we do not claim cultural homogeneity across this group of people. Indeed, cultural differences, if any, between these nationalities indicated do not have any major implications in the way they are treated with regards to health care delivery in China. In fact, Chinese, whether at the government level or at individual levels tend to treat and interact with Africans as a homogenous group, especially with regards to health care (non)-delivery.

References

International Organization for migration about migration: facts & figures. 2010. http://www.iom.int/jahia/Jahia/about-migration/facts-and-figures/lang/en. Accessed 15 April 2012.

International Organization for Migration. World Migration Report 2011: Communicating effectively about migration, Switzerland (2011).

Gushulak B, Weekers J, Macpherson D. Migrants and emerging public health issues in a globalized world: threats, risks and challenges, an evidence-based framework. Emerg Health Threats J. 2009;2:e10. doi:10.3134/ehtj.09.010.

Guirgis M, Nusair F, Bu YM, Yan K, Zekry AT. Barriers faced by migrants in accessing healthcare for viral hepatitis infection. Intern Med J. 2012;42(5):491–6. doi:10.1111/j.1445-5994.2011.02647.x.

Harari N, Davis M, Heisler M. Strangers in a strange land: health care experiences for recent Latino immigrants in Midwest communities. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008;19(4):1350–67. doi:10.1353/hpu.0.0086.

Ku L, Freilich A. Caring for immigrants: health care safety nets in Los Angeles, New York, Miami, and Houston. The Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the uninsured (2001).

Morales LS, Lara M, Kington RS, Valdez RO, Escarce JJ. Socioeconomic, cultural, and behavioral factors affecting Hispanic health outcomes. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2002;13(4):477–503. doi:10.1177/104920802237532.

Magalhaes L, Carrasco C, Gastaldo D. Undocumented migrants in Canada: a scope literature review on health, access to services, and working conditions. J Immigr Minor Health. 2010;12(1):132–51. doi:10.1007/s10903-009-9280-5.

Wolff H, Epiney M, Lourenco AP, Costanza MC, Delieutraz-Marchand J, Andreoli N, Dubuisson JB, Gaspoz JM, Irion O. Undocumented migrants lack access to pregnancy care and prevention. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:93. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-8-93.

Jatrana S, Toyota M, Yeoh B. Migration and Health in Asia Routledge. OX: Abingdon; 2006.

National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China Major figures on residents from Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan and foreigners covered by 2010 population census. 2011. http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/newsandcomingevents/t20110429_402722638.htm. Accessed 15 April 2012.

Bodomo AB. The African trading community in Guangzhou: an emerging bridge for Africa-China Relations. China Q. 2010;203:693–707. doi:10.1017/S0305741010000664.

Bodomo AB. Africans in China: a sociocultural study and its implications on Africa–China relations. Cambria Press; 2012.

Zhao S The China–Angola Partnership: a case study of China’s oil relations in Africa. http://www.china-briefing.com/news/2011/05/25/the-china-angola-partnership-a-case-study-of-chinas-oil-relationships-with-african-nations.html. 2011. Accessed April 16 2012.

Perlez J With $20 billion loan pledge, China strengthens its ties to African nations. The New York Times; 2012.

Zhang L. Ethnic congregation in a globalizing city: the case of Guangzhou, China. Cities. 2008;25(6):383–95. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2008.09.004.

Li Z, Xue D, Lyons M, Brown A. The African enclave in Guangzhou: a case study of Xiaobeilu. J Geogr Sci. 2008;63(2):207–18.

McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1988;15:351–77. doi:10.1177/109019818801500401.

Aday LA, Andersen R. A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Serv Res. 1974;9(3):208–20.

Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(1):1–10.

GmbH VERBI. MAXQDA, software for qualitative data analysis. Germany: Berlin-Marburg-Amöneburg; 2011.

Babitsch B, Gohl D, von Lengerke T Re-revisiting Andersen’s behavioral model of health services use: a systematic review of studies from 1998–2011. Psychosoc Med. 2012; doi:10.3205/psm000089.

Aroian KJ, Wu B, Tran TV. Health care and social service use among Chinese immigrant elders. Res Nurs Health. 2005;28(2):95–105. doi:10.1002/nur.20069.

Amnesty International People’s Republic of China: internal migrants: discrimination and abuse. The human cost of an economic ‘Miracle’. 2007. http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/info/ASA17/008/2007. (2012).

Shaokang Z, Zhenwei S, Blas E. Economic transition and maternal health care for internal migrants in Shanghai, China. Health Policy Plan. 2002;17(Suppl):47–55. doi:10.1093/heapol/17.suppl_1.47.

Babiarz KS, Miller G, Yi H, Zhang L, Rozelle S. New evidence on the impact of China’s new rural cooperative medical scheme and its implications for rural primary healthcare: multivariate difference-in-difference analysis. BMJ. 2010;341:c5617. doi:10.1136/bmj.c5617.

Cui Y, Gu L Curbing influx of illegal aliens. China Daily; 2012.

Chetail V, Giacca G Who cares? The right to health of migrants. In: Robinson M, Clapham A, editors. Realizing the right to health: Swiss Human Rights Book vol 3. Ruffer & Rub Pub; 2009. pp 224–234.

Hesketh T, Wu D, Mao L, Ma N. Violence against doctors in China. BMJ. 2012;345:e5730. doi:10.1136/bmj.e5730.

Violence against doctors: Why China? Why now? What next? Lancet 2014; 383 (9922):1013. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60501-8.

Xu Z (2013) The distortion of the doctor–patient relationship in China. http://www.sgim.org/File%20Library/SGIM/Resource%20Library/Forum/2014/Feb2014-01.pdf.

Yeo S. Language barriers and access to care. Annu Rev Nurs Res. 2004;22:59–73.

Freeman G, Lethbridge-Cejku M Access to health care among Hispanic or Latino Women: United States, 2000–2002. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad368.pdf. (2006). Accessed 16 April 2012.

The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation Key facts: race, ethnicity and medical care. http://www.kff.org/minorityhealth/upload/6069-02.pdf. 2007. Accessed April 16 2012.

Flores G. The impact of medical interpreter services on the quality of health care: a systematic review. Med Care Res Rev. 2005;62(3):255–99. doi:10.1177/1077558705275416.

Karliner LS, Jacobs EA, Chen AH, Mutha S. Do professional interpreters improve clinical care for patients with limited English proficiency? A systematic review of the literature. Health Services Res. 2007;42(2):727–54. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00629.x.

Anderson LM, Scrimshaw SC, Fullilove MT, Fielding JE, Normand J, Task force on community preventive S culturally competent healthcare systems. A systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2003; 24 (3 Suppl):68–79.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Guangzhou African community leaders, Ojukwu Emma and Sultane Barry, for organizing community events. The authors would also like to thank the African migrants in Guangzhou for their time and effort. Preparation of this article was supported in part by grants from the NIH FIC (1K01TW008200-01A3) and Emory Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI050409; Wong and Nehl).

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, L., Brown, K.B., Yu, F. et al. Health Care Experiences and Perceived Barriers to Health Care Access: A Qualitative Study Among African Migrants in Guangzhou, Guangdong Province, China. J Immigrant Minority Health 17, 1509–1517 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-014-0114-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-014-0114-8