Abstract

Given heterogeneous evidence regarding the impacts of migration on HIV/sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among female sex workers (FSWs), we explored factors associated with international migration among FSWs in Vancouver, Canada. We draw on baseline questionnaire and HIV/STI testing data from a community-based cohort, AESHA, from 2010-2012. Logistic regression identified correlates of international migration. Of 650 FSWs, 163 (25.1 %) were international migrants, who primarily worked in formal indoor establishments. HIV/STI prevalence was lower among migrants than Canadian-born women (5.5 vs. 25.9 %). In multivariate analysis, international migration was positively associated with completing high school, supporting dependents, and paying a third party, and negatively associated with HIV, injecting drugs and inconsistent condom use with clients. Although migrants experience lower workplace harms and HIV risk than Canadian-born women, they face concerning levels of violence, police harassment, and HIV/STIs. Research exploring structural and socio-cultural factors shaping risk mitigation and migrants’ access to support remains needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

There are an estimated 214 million international migrants worldwide [1]. Women comprise a large proportion of migrants [2–4], representing almost half of migrants globally. Women seeking a better livelihood often migrate to improve their economic situation, for reasons including economic and gender disparities, subsistence needs, family obligations, and a desire for social mobility. Some women may migrate for the purposes of sex work, whereas others may enter sex work during or following migration for reasons such as remittance pressures and limited formal sector employment opportunities [5–9].

Migration plays a key role in shaping risks and protective factors for HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) [9–13]. Female migrants in many lower-income settings—especially those who engage in sex work—often experience substantial health-related vulnerabilities, including HIV and STIs, violence, and poor reproductive health [11, 13–21]. However, a recent systematic review among female sex workers (FSWs) identified substantial heterogeneity in the health consequences of migration. Whereas migrant FSWs across all settings experienced increased risk of STIs, only those in lower-income countries were also at elevated risk of HIV. Although working in higher-income European countries conferred protection for HIV [13], evidence from other high-income settings in North America, where migrants are more likely to represent Asian and Latin American countries of origin, remains lacking.

Migration may concomitantly facilitate new risks as well as opportunities. Among FSWs in South Africa, international migration facilitated social and economic opportunities (e.g., higher income), as well as reduced contact with health providers and lower condom use as compared to internal migrants [22]. Studies among Mexico-US migrants also suggest that whereas migration may increase sexual risks (e.g., increased sexual partners), it can also facilitate condom use and access to care [5, 23, 24]. In light of evidence suggesting heterogeneity and complexity in the health consequences of migration, we undertook this study to examine the linkages between migration and HIV/STI risk and protective factors among FSWs in Canada.

Canada is the second largest destination country for international migrants in the Americas, with an estimated 7.2 million international migrants [3]. In Canada, as in most settings globally, sex work is criminalized. While there is variation by work environments, sex workers in Canada often experience heightened vulnerabilities to HIV and STIs, illicit drug use and violence, as well as barriers to accessing care, which have been largely attributed to social and structural conditions [25–29]. This study was conducted in Vancouver, British Columbia (BC), where the majority of international migrants are of Asian descent. Although no reliable statistics exist on migrant FSWs in Vancouver, a significant proportion are believed to be foreign-born [30]. Qualitative data indicate that among some migrant FSWs, language barriers and limited access to services and immigration information may increase vulnerability to mistreatment and abuse [30]. Further, the criminalization of sex work has been shown to facilitate poor working conditions, violence, and reduced condom negotiation abilities for FSWs in Canada, which may disproportionately impact migrants by pushing them further underground due to fears of police and immigration authorities [30]. Despite these concerns, epidemiological evidence regarding the health and working conditions of migrants in Canada’s sex industry remain poorly understood.

Theoretical/Conceptual Framework

Health outcomes such as HIV/STIs are the product of endogenous and exogenous influences [26, 31–35], including individual, interpersonal and behavioural, and social and structural factors [36]. Among migrant FSWs, HIV vulnerability can be influenced by social and structural determinants such as working conditions (e.g., exploitation; violence; manager roles), immigration-related barriers to care, remittance pressures, linguistic and cultural differences, and ethnic discrimination; interpersonal and behavioral factors such as exposure to new risk behaviors (e.g., drug use) and gendered barriers to condom use; and individual factors such as STI co-infection and epidemic stage (e.g., endemic vs. non-endemic) in origin and destination settings [5, 6, 9–11, 13, 20, 23, 30, 37–44]. At the same time, mobility may also offer an avenue for mitigating HIV risk, such as through protective socio-cultural norms (e.g., taboos against drug use; cultural/social supports) and the increased earnings afforded by migration to high-income settings, with evidence suggesting that migration-related health consequences may ultimately depend on its context and drivers [9, 13, 45–47].

Gaps on Epidemiological Data Among Migrant Sex Workers in High-Income Settings

Although recent studies have highlighted the importance of social and structural factors associated with HIV among FSWs, including violence and criminalization [6, 25, 29, 48–50], little is known about the health and safety of migrant FSWs in higher-income countries. This study sought to identify associations between international migration and individual, interpersonal/behavioural, and social/structural factors hypothesized to mitigate or confer HIV/STI risk among FSWs in Vancouver, Canada.

Methods

Data Collection

Baseline data was drawn from an open prospective cohort, An Evaluation of Sex Workers Health Access (AESHA) between January 2010 and August 2012. This study was developed based on collaborations developed since 2005 [51] and is monitored by a Community Advisory Board encompassing 15+ organizations. All procedures were approved by the Providence Health Care/University of British Columbia Research Ethics Board.

Participants

Eligibility criteria included self-identifying as female (including transgender (male-to-female)), being ≥14 years old, having exchanged sex for money within the last 30 days and providing written informed consent. Given the challenges of recruiting FSWs in isolated and hidden locations [52], time-location sampling was used to recruit FSWs through outreach to street- and off-street settings (e.g., online, newspaper, massage parlours, micro-brothels, other in-call locations) across Metro Vancouver. Sex work venues were identified through community mapping [51] and updated regularly. Women were given the option of completing questionnaires at study offices or at their work or home location. Participants received $40 CAD at each visit for their time, expertise and travel.

Measures

Dependent Variable

The dependent variable was migrating to Canada from another country (i.e., international migration) at baseline, which was based on a “no” response to the question, “Were you born in Canada?”

Independent Variables of Interest

Participants completed interviewer-administered questionnaires in English, Mandarin or Cantonese by trained interviewers and HIV/STI testing by a project nurse. The baseline questionnaire covered socio-demographic characteristics such as age, education, and languages spoken. Financial support of dependents was assessed by asking, “Does anyone depend on you for financial support (including food, shelter, clothing, necessities)?” Sexual risks (e.g., age at sex work entry, condom negotiation) and drug use (e.g., non-injection and injection drug use) were also measured. Inconsistent condom use with clients was defined as ‘usually’, ‘sometimes’, ‘occasionally’, or ‘never’ using a condom for vaginal/anal sex with one-time/regular clients (vs. ‘always’ used condoms). Work environment included primary places of solicitation and servicing clients, physical conditions of street and indoor venues, establishment policies, interactions with third parties (e.g., managers), police, security, city licensing, and workplace violence. Place of service was based on primary place reported in response to “In which of the following types of places have you ever serviced/taken clients?” in the last 6 months, and coded as outdoor/public (e.g., street, vehicle, other public areas), informal indoor (e.g., drug house, bar, nightclub, hotel, client’s place, your place, supportive housing), and formal indoor establishment/brothel (e.g., massage parlour, health/beauty enhancement centre, micro-brothel). Workplace violence was assessed by asking if participants experienced verbal, physical, sexual and/or sexual violence in the last 6 months by clients (including abducted/kidnapped, forced unprotected sex, raped, strangled, physical assault, assaulted with a weapon). Third party influences were assessed by asking if participants had ever paid or had to share a portion of their income from clients with a third party (e.g., manager, administrator). Past coercion/exploitation was measured by a response of “Turned out (coerced into work)” to the question, “How did you first get into sex work?”

HIV/STI Measures

Following pre-test counseling, Biolytical INSTI [Biolytical Laboratories Inc, Richmond, BC] rapid point-of-care tests were used for HIV screening, with reactive tests confirmed by western blot. Urine samples were collected for gonorrhea and chlamydia, and blood was drawn for syphilis testing. All participants received post-test counseling. STI treatment was provided by a project nurse onsite. Free serology and Papanicolaou testing were made available, regardless of study enrolment. STI/HIV infection was defined as positive for any STI (syphilis, gonorrhea, or Chlamydia) or HIV at baseline.

Analysis

We conducted univariate and multivariate logistic regression to evaluate differences in individual, interpersonal/behavioural and social/structural factors between international migrants versus Canadian-born FSWs. Variables a priori hypothesized to be related to international migration and with a significance level of less than 10 % in univariate analyses were considered for inclusion in the multivariate model. Model selection was constructed using a backward process. Akaike’s Information Criteria was used to determine the most parsimonious model. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (Cary, NC). All p-values are two sided.

Results

Of 650 FSWs, 163 (25.08 %) were international migrants, who were primarily Chinese migrants (76.69 %, n = 125). International migrants had spent a median of 6 years in Canada (Inter-quartile range (IQR): 4–11), and reported feeling most comfortable speaking Mandarin (66.26 %, n = 108), followed by English (16.56 %, n = 27) and Cantonese (11.66 %, n = 19).

Individual Factors and HIV/STI Prevalence

In comparison with Canadian-born women, migrants were more likely to initiate sex work at an older age (median age: 33 vs. 18, p < 0.001) and to have completed high school (Table 1). Combined HIV/STIs prevalence was 20.77 % across the sample, which was lower among international migrants than Canadian-born women (5.52 vs. 25.87 %, Odds Ratio (OR): 0.17, 95 % Confidence Interval (CI): 0.08-0.34). Migrants were less likely than Canadian-born sex workers to report prior mental health diagnoses (18.40 vs. 59.14 %, p < 0.001) .

Interpersonal and Behavioral Factors

International migrants consistently reported a lower-risk profile of interpersonal and behavioral factors. They were less likely than Canadian-born FSWs to use illicit injected (6.75 vs. 51.75 %, OR 0.07, 95 % CI 0.04–0.13) or non-injected drugs (14.72 vs. 88.71 %, OR 0.02, 95 % CI 0.01–0.04) in the past 6 months. Across the sample, 17.38 % of FSWs reported inconsistent condom use with clients, which was significantly lower among migrant versus Canadian-born FSWs (4.91 vs. 21.56 %, OR 0.19, 95 % CI 0.09–0.40).

Social and Structural Factors

Women’s exposure to social and structural risks greatly differed by international migration status. Migrants predominantly worked in formal indoor establishments or brothels (86.50 %, n = 141), as compared with Canadian-born FSWs, who primarily worked in outdoor/public (57.08 %, n = 278) or informal indoor (32.65 %, n = 159) spaces. Migrants were more likely than Canadian-born women to financially support dependents (52.76 vs. 18.28 %, OR 5.0, 3.40-7.33); among migrants with financial dependents, primary dependents supported included children (73.26 %), parents (34.8 %) and siblings/extended family (9.30 %). In terms of living arrangements, migrants were more likely than non-migrants to live with their children (36.81 vs. 3.08 %), intimate partners/spouses (23.31 vs. 14.78 %), or other family (15.34 vs. 4.31 %).

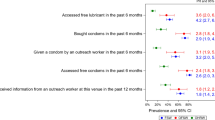

Compared to the working conditions of Canadian-born participants, migrants were more likely to report paying third parties (e.g., manager) (88.96 vs. 35.73 %, OR 14.49, 95 % CI 8.58–24.46), and were less likely to report prior coercion (1.84 vs. 12.73 %, OR 0.13, 95 % CI 0.04–0.42) or recent exposure to client violence (19.02 vs. 45.79 %, OR 0.28, 95 % CI 0.18–0.43). In terms of law enforcement interactions, migrants reported concerning levels of police harassment (17.18 %), raids at their workplace (10.4 %), police abuse (including physical assault or coerced into sexual favours) (3.3 %), and arrest on prostitution charges (2.24 %), as well as combined lifetime exposure to these police interactions (18.40 %). Whereas similar proportions of migrant and non-migrant women reported barriers to health care, migrants were less likely to recently use sexual/reproductive health services (10.43 vs. 38.40 %).

Univariate and Multivariate Analyses

In multivariate analysis (Table 2), international migration was independently and positively associated with high school completion (Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) 3.90, 95 % CI 2.30–6.59), financially supporting dependents (AOR 2.81, 95 % CI 1.71–4.62), and paying a third party (AOR 8.20, 95 % CI 4.61-14.60). International migration was negatively associated with HIV infection (AOR 0.09, 95 % CI 0.01–0.79), as well as recent sexual and drug-related risks such as injection drug use (AOR 0.14, 95 % CI 0.07–0.28) and inconsistent condom use with clients (AOR 0.32, 95 % CI 0.14–0.75).

Discussion

In this study, international migrants in the sex industry reported lower workplace HIV/STI risks, drug use, and past coercion than their Canadian-born peers, suggesting that migration to Canada may confer protection against HIV/STIs among sex workers. However, the persistent health challenges (e.g., combined HIV/STI prevalence of 5.5 %), high levels of workplace violence (19 %) and police raids, harassment, abuse, or arrest (18.40 %), and inequities in access to sexual and reproductive health services faced by migrants confirm the need for ongoing, culturally appropriate outreach to promote health and reduce harm among migrant sex workers.

Whereas most previous studies have suggested that migrant FSWs in lower-income settings experience enhanced HIV-related vulnerabilities [13–18], findings of this study indicate that international migration may be linked to lower HIV/STI risks in higher-income settings such as Canada. These results are supported by findings of a recent review suggesting the same to be true among migrant FSWs in high- and upper middle- income countries in Europe and Latin America [13]. In comparison with non-migrants, lower HIV prevalence was found among migrant FSWs in Portugal, Argentina, and Ecuador [13, 38, 53], which may be explained by high prevalence of drug use among non-migrant FSWs in these countries [38]. In this study, migration also related to lower drug use and sexual risks. Although future research is needed to understand the context of HIV risk mitigation and substance use for migrants, our results may be explained by cultural and social factors among Asian FSWs, such as taboos against drug use and norms regarding gender roles and sexual behaviour. Indeed, migrants may arrive in new destinations with protective characteristics and behaviors (i.e., the ‘healthy migrant effect’), and adopt higher-risk behaviors (e.g., substance use) that resemble the profile of their Canadian-born peers over time, as has been demonstrated in some studies of Mexico-U.S. migrants [54–58]. In Vancouver, the concentration of Chinese FSWs in Asian staffed- and operated- establishments (e.g., massage parlours, health enhancement centres) may limit social and cultural integration, buffering migrants from the higher-risk experiences often reported by street-based FSWs. Clearly, variation exists in the social, structural and cultural contexts experienced by migrants across settings, indicating the need for further studies to deepen our understanding of social and cultural aspects of risk and prevention for migrants in distinct communities to inform culturally tailored interventions [59].

This study contributes to our understanding of how the social and structural conditions migrants face may be responsible for heterogeneity in the relationship between migration and HIV risk. We found that international migrants were more likely to work in formal indoor establishments and to report safer working conditions, including lower exposure to violence than non-migrants, and were less likely to have been diagnosed with mental health issues. Contrary to concerns regarding the trafficking of foreign-born women [60], migrants were less likely to report past coercion/trafficking. These findings may be explained by features of the environments in which migrant FSWs operate, such as managerial policies and practices in indoor venues. Indeed, a recent review concluded that inconsistent data regarding whether or not migrants face increased risk of HIV, particularly in high-income countries, may be attributable to the heterogeneous organization of sex work in these settings [13]. Research is needed to understand potentially protective aspects of indoor sex work environments (e.g., supportive workplace sexual health policies; protective managerial roles; policies to discourage violence). In Canada, legislative changes are being contemplated that may ultimately decriminalize sex work, which provide a unique opportunity to evaluate the impacts of shifting legal and policy environments among migrant FSWs. Evidence from Canada [25–29, 61, 62] and elsewhere [6, 50, 63–66] suggests that criminalization of sex work can increase HIV/STI risk and violence, for example, through displacement of FSWs to higher-risk settings and fear of disclosing sex work involvement to providers. Qualitative research from Vancouver suggests that racialized populations, such as migrant and Indigenous sex workers, may be disproportionately impacted by criminalization and enforcement, through fear and distrust of police and other authorities, and lack of protections [28, 67]. Almost one-fifth of migrant FSWs experienced heightened police surveillance, harassment and arrest, and evidence suggests that the removal of criminal sanctions and law enforcement targeting sex workers can promote improved health and safety, including the ability to safely access police protections for violence and abuse, and workplace safety standards [68, 69]. However, potential concerns around immigration and access to care for migrant sex workers may impede these changes.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

The cross-sectional nature of these data cannot be used to infer causality. Since the study from which these findings were generated was not designed to investigate the relationship between HIV/STIs and migration patterns, additional studies are needed to understand broader determinants of migrant FSWs’ health. Studies that gather more detailed data regarding the diverse contexts surrounding migration (e.g., reasons for migration, immigration status) as well as the timing and nature of migration and HIV-related risks are needed to explore pathways and contexts of risk and risk mitigation. Future research is also needed to establish the extent to which differences in self-reported mental health may relate to lower access to care or different cultural perceptions of mental health. Given the large proportion of Mandarin-speaking FSWs in formal indoor establishments in Vancouver and the fact that the majority of recent international migrants to Vancouver are of Asian origin, our questionnaire was offered in Mandarin, Cantonese and English. It is possible that recent migrants from other settings and more hidden migrants, such as undocumented workers and trafficked women, may be under-represented, which may explain why our study was more likely to detect protective factors associated with migration. Larger studies are needed explicitly focused on the needs of migrant FSWs from diverse contexts and those in more “hidden” settings.

Conclusion

These findings indicate that international migration may be linked to a reduced likelihood of drug use and lower exposure to sexual risks among sex workers in Vancouver, Canada. Further, international migrants were less likely than Canadian-born women to experience risks related to social and structural conditions, such as exploitation or workplace violence. Findings support the contention that the health impacts of migration greatly depend on the social and structural context surrounding sex work. Future research in collaboration with sex work and migrant communities is required to elucidate the social and cultural context of HIV/STI risk and risk mitigation among migrant sex workers, both in Canada and internationally. The development and implementation of culturally appropriate, evidence-based HIV/STI prevention for migrants is needed.

References

International Organization for Migration. Facts and figures. 2013.

Kanaiaupuni SM. Reframing the migration question: an analysis of men, women, and gender in Mexico. Soc Forces. 2000;78:1311–47.

International Organization for Migration. Facts and figures: Americas. 2012.

Massey DS, Fischer MJ, Capoferro C. International Migration and gender in Latin America: a comparative analysis. Int Migr. 2006;44:63–91.

Goldenberg S, Strathdee S, Perez-Rosales M, Sued O. Mobility and HIV in Central America and Mexico: A Critical Review. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14:48–64.

Yi HS, Mantell JE, Wu RR, Lu Z, Zeng J, et al. A profile of HIV risk factors in the context of sex work environments among migrant female sex workers in Beijing, China. Psychol Health Med. 2010;15:172–87.

Jie W, Xiaolan Z, Ciyong L, Moyer E, Hui W, et al. A qualitative exploration of barriers to condom use among female sex workers in China. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e46786.

Ragsdale K, Anders JT, Philippakos E. Migrant Latinas and brothel sex work in Belize: sexual agency and sexual risk. J Cult Divers. 2007;14:26–34.

Goldenberg S, Silverman J, Engstrom D, Bojorquez-Chapela I, Strathdee S. “Right here is the gateway”: mobility, sex work entry and HIV risk along the Mexico-U.S. border. International Migration. 2013. doi:10.1111/imig.12104.

Ferguson AG, Morris CN. Mapping transactional sex on the Northern Corridor highway in Kenya. Health Place. 2007;13:504–19.

Goldenberg SM, Strathdee SA, Perez-Rosales MD, Sued O. Mobility and HIV in Central America and Mexico: a critical review. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14:48–64.

Lagarde E, Schim van der Loeff M, Enel C, Holmgren B, Dray-Spira R, et al. Mobility and the spread of human immunodeficiency virus into rural areas of West Africa. Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32:744–52.

Platt L, Grenfell P, Fletcher A, Sorhaindo A, Jolley E, et al. Systematic review examining differences in HIV, sexually transmitted infections and health-related harms between migrant and non-migrant female sex workers. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89:311–9.

Adanu RMK, Johnson TRB. Migration and women’s health. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2009;106:179–81.

Collins SP, Goldenberg SM, Burke NJ, Bojorquez-Chapela I, Silverman JG, et al. Situating HIV risk in the lives of formerly trafficked female sex workers on the Mexico–US border. AIDS Care. 2013;25:459–65.

Silverman JG, Decker M, Gupta J, Maheshwari A, Willis B, et al. HIV prevalence and predictors of infection in sex-trafficked nepalese girls and women. J Am Med Assoc. 298:536–42.

Uribe-Salas F, Conde-Glez CJ, Juarez-Figueroa L, Hernandez-Castellanos A. Sociodemographic dynamics and sexually transmitted infections in female sex workers at the Mexican-Guatemalan border. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30:266–71.

Platt L, Grenfell P, Bonell C, Creighton S, Wellings K, et al. Risk of sexually transmitted infections and violence among indoor-working female sex workers in London: the effect of migration from Eastern Europe. Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87:377–84.

Kendall T, Pelcastre BE. HIV vulnerability and condom use among migrant women factory workers in Puebla, Mexico. Health Care Women Int. 2010;31:515–32.

Bronfman MN, Leyva R, Negroni MJ, Rueda CM. Mobile populations and HIV/AIDS in Central America and Mexico: research for action. AIDS. 2002;16:S42–9.

Lindstrom DP, Hernandez CH. Internal migration and contraceptive knowledge and use in Guatemala. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2006;32:146–53.

Richter M, Chersich M, Vearey J, Sartorius B, Temmerman M, et al. Migration status, work conditions and health utilization of female sex workers in three south African cities. J Immigr Minority Health. 2014;16:7–17.

Goldenberg S, Strathdee S, Gallardo M, Patterson T. “People Here Are Alone, Using Drugs, Selling their Body”: Deportation and HIV vulnerability among clients of female sex workers in Tijuana. Field actions science reports 2010;1–7.

Fosados R, Caballero-Hoyos R, Torres-López T, Valente T. Condom use and migration in a sample of Mexican migrants: potential for HIV/STI transmission. Salud Pública de México. 2006;48:57–61.

Shannon K, Kerr T, Strathdee SA, Shoveller J, Montaner JS, et al. Prevalence and structural correlates of gender based violence among a prospective cohort of female sex workers. Br Med J. 2009;339:b2939.

Shannon K, Kerr T, Allinott S, Chettiar J, Shoveller J, et al. Social and structural violence and power relations in mitigating HIV risk of drug-using women in survival sex work. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:911–21.

Shannon K, Rusch M, Shoveller J, Alexson D, Gibson K, et al. Mapping violence and policing as an environmental-structural barrier to health service and syringe availability among substance-using women in street-level sex work. Int J Drug Policy. 2008;19:140–7.

Shannon K, Bright V, Gibson K, Tyndall MW. Sexual and drug-related vulnerabilities for HIV infection among women engaged in survival sex work in Vancouver, Canada. Can J Public Health. 2007;98:465–9.

Shannon K, Strathdee SA, Shoveller J, Rusch M, Kerr T, et al. Structural and environmental barriers to condom use negotiation with clients among female sex workers: implications for HIV-prevention strategies and policy. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:659–65.

Pivot Legal Society. Beyond decriminalization: sex work, human rights and a new framework for law reform: abridged version: pivot legal society. 2006.

Aral SO, Padian NS, Holmes KK. Advances in multilevel approaches to understanding the epidemiology and prevention of sexually transmitted infections and HIV: an overview. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:S1–6.

Rhodes T, Singer M, Bourgois P, Friedman SR, Strathdee SA. The social structural production of HIV risk among injecting drug users. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:1026–44.

Rhodes T. Risk environments and drug harms: a social science for harm reduction approach. Int J Drug Policy. 2009;20:193–201.

Rhodes T. The ‘risk environment’: a framework for understanding and reducing drug-related harm. Int J Drug Policy. 2002;13:85–94.

Shannon K, Goldenberg SM, Deering K, Strathdee SA. HIV Infection among Female Sex Workers in Concentrated and High Prevalence Epidemics: Why a Structural Determinants Framework is Needed. Current opinion in HIV and AIDS. 2014;9:174-82.

Baral S, Beyrer C, Muessig K, Poteat T, Wirtz AL, et al. Burden of HIV among female sex workers in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:538–49.

Busza J. Sex work and migration: the dangers of oversimplification: a case study of Vietnamese women in Cambodia. Health Human Rights. 2004;7:231–49.

Bautista C, Mosquera C, Serra M, Gianella A, Avila M, et al. Immigration status and HIV-risk related behaviors among female sex workers in South America. AIDS Behav. 2008;12:195–201.

Wolffers I, van Beelen N. Public health and the human rights of sex workers. Lancet. 2003;361:1981.

Zimmerman C, Hossain M, Yun K, Roche B, Morison L, et al. Stolen smiles: a summary report on the physical and psychological health consequences of women and adolescents trafficked in Europe: London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. 2006.

Jemmott LS, Maula EC, Bush E. Hearing our voices: assessing HIV prevention needs among Asian and Pacific Islander women. J Transcult Nurs. 1999;10:102–11.

Nemoto T, Iwamoto M, Wong S, Le M, Operario D. Social factors related to risk for violence and sexually transmitted infections/HIV among Asian massage parlor workers in San Francisco. AIDS Behav. 2004;8:475–83.

Nemoto T, Iwamoto M, Oh HJ, Wong S, Nguyen H. Risk behaviors among Asian women who work at massage parlors in San Francisco: perspectives from masseuses and owners/managers. AIDS Educ Prev. 2005;17:444–56.

Rushing R, Watts C, Rushing S. Living the reality of forced sex work: perspectives from young migrant women sex workers in Northern Vietnam. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2005;50:e41–4.

Mayer JD. Geography, ecology and emerging infectious diseases. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:937–52.

International Organization for Migration. HIV and population mobility. 2013.

Strathdee SA, Lozada R, Ojeda VD, Pollini RA, Brouwer KC, et al. Differential effects of migration and deportation on HIV infection among male and female injection drug users in Tijuana, Mexico. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2690.

Kerrigan D, Ellen JA, Moreno L, Rosario S, Katz J, et al. Environmental-structural factors significantly associated with consistent condom use among female sex workers in the Dominican Republic. AIDS. 2003;17:415–23.

Simic M, Rhodes T. Violence, dignity and HIV vulnerability: street sex work in Serbia. Sociol Health Illn. 2009;31:1–16.

Strathdee SA, Lozada R, Martinez G, Vera A, Rusch M, et al. Social and structural factors associated with HIV infection among female sex workers who inject drugs in the Mexico-US border region. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e19048.

Shannon K, Bright V, Allinott S, Alexson D, Gibson K, et al. Community-based HIV prevention among substance-using women in survival sex work: the Maka Project Partnership. Harm Reduct J. 2007;4:20.

Stueve A, O’Donnell LN, Duran R, San Doval A, Blome J. Time-space sampling in minority communities: results with young Latino men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:922–6.

Day S, Ward H. Approaching health through the prism of stigma: research in seven European countries. Sex work, mobility and health in Europe, p. 139–59. 2004.

Gfroerer JC, Tan LL. Substance use among foreign-born youths in the United States: does the length of residence matter? Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1892.

Guilamo-Ramos V, Jaccard J, Pena J, Goldberg V. Acculturation-related variables, sexual initiation, and subsequent sexual behavior among Puerto Rican, Mexican, and Cuban youth. Health Psychol. 2005;24:88–95.

Kaplan MS, Huguet N, Newsom JT, McFarland BH. The association between length of residence and obesity among Hispanic immigrants. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:323–6.

Hines AM, Snowden LR, Graves KL. Acculturation, alcohol consumption and AIDS-related risky sexual behavior among African American women. Women Health. 1998;27:17–35.

Kandula NR, Kersey M, Lurie N. Assuring the health of immigrants: what the leading health indicators tell us. Annu Rev Public Health. 2004;25:357–76.

Acevedo-Garcia D, Sanchez-Vaznaugh EV, Viruell-Fuentes EA, Almeida J. Integrating social epidemiology into immigrant health research: a cross-national framework. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75:2060–8.

Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). Human trafficking in Canada: a threat assessment. Ottawa, ON: RCMP Criminal Intelligence; 2010.

Shannon K, Csete J. Violence, condom negotiation, and HIV/STI risk among sex workers. J Am Med Assoc. 2010;304: 573–4.

Goldenberg SM, Chettiar J, Simo A, Silverman JG, Strathdee SA, et al. Early sex work initiation independently elevates odds of HIV infection and police arrest among adult sex workers in a Canadian setting. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;65:122-8.

Blankenship KM, Koester S. Criminal law, policing policy, and HIV risk in female street sex workers and injection drug users. J Law Med Ethics. 2002;30:548–59.

Pando MA, Coloccini RS, Reynaga E, Rodriguez Fermepin M, Gallo Vaulet L, et al. Violence as a barrier for HIV prevention among female sex workers in Argentina. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e54147.

Beletsky L, Martinez G, Gaines T, Nguyen L, Lozada R, et al. Mexico’s northern border conflict: collateral damage to health and human rights of vulnerable groups. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública. 2012;31:403–10.

Rhodes T, Simić M, Baroš S, Platt L, Žikić B. Police violence and sexual risk among female and transvestite sex workers in Serbia: qualitative study. Br Med J 2008;337:a811.

Anderson S, Jia Xi, Homer J, Krusi A, Maher L, Shannon K. Licensing, policing and safety in indoor sex work establishments in the greater Vancouver area: narratives of migrant sex workers, managers and business owners (Under Review).

Shannon K, Csete J. Violence, condom negotiation, and HIV/STI risk among sex workers. JAMA. 2010;304:573–4.

World Health Organization. WHO guidelines: prevention and treatment of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections for sex workers in low- and middle-income countries. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by operating grants from the US National Institutes of Health (R01DA028648) and Canadian Institutes of Health Research (HHP-98835). SG is supported by postdoctoral fellowships from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research/Women’s Health Research Initiative. KS is supported by US National Institutes of Health (R01DA028648), Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Goldenberg, S.M., Liu, V., Nguyen, P. et al. International Migration from Non-endemic Settings as a Protective Factor for HIV/STI Risk Among Female Sex Workers in Vancouver, Canada. J Immigrant Minority Health 17, 21–28 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-014-0011-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-014-0011-1