Abstract

Although 54 % of the total black immigrant population is from the Caribbean and 34 % is from Africa, we know relatively little about barriers to healthcare access faced by black immigrants. This paper reviews literature on the barriers that black immigrants face as they traverse the healthcare system and develops a conceptual framework to address barriers to healthcare access experienced by this population. Our contribution is twofold: (1) we synthesize the literature on barriers that may lead to inequitable healthcare access for black immigrants, and (2) we offer a theoretical perspective on how to address these barriers. Overall, the literature indicates that structural barriers can be overcome by providing interpreters, cultural competency training for healthcare professionals, and community-based care. Our model reflects individual and structural factors that may promote these initiatives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

According to the 2009 United States Census, 1 in 8 US residents is foreign born. Moreover, the number of immigrants living in the US is expected to grow to 19 %, or 1 in 5, by the year 2050 [1, 2]. Two significant groups of immigrants in regard to size are those born in Africa and those born in the Caribbean. In 2007, black immigrants made up over 8 % (more than 3 million) of the total US foreign-born population [3]. It has also been reported that the black immigrant population may account for as much at 13 % of the foreign-born population in the US, with black Caribbean making up 9 % and black Africans 4 % of the total US immigrant community [4]. Moreover, of the total black immigrant population, 54 and 34 % are from the Caribbean and Africa, respectively [1]. Despite these relatively high percentages, we know very little about the factors that influence healthcare access in these communities.

To date, published research indicates that black immigrants face significant challenges in regard to healthcare access. Such challenges include lack of health insurance [5–8], lack of interpreters [7–10], discrimination based on race or accent [11–14], and lack of understanding on the part of doctors regarding African and Caribbean perspectives on illness [11, 15, 16]. However even though studies have identified these challenges, there is still a dearth of information about exactly how healthcare barriers reduce access to care for African- and Caribbean-born people living in the US. It is important, then, to learn more about the barriers to healthcare faced by black immigrants, as such are likely to have important implications for the overall health of this population.

This paper reviews the literature on barriers faced by black immigrants that impact their access to health care. Our contribution is twofold: (1) we synthesize the literature on barriers to healthcare access faced by black immigrants, and (2) we offer a theoretical perspective on how to address these barriers.

Methods

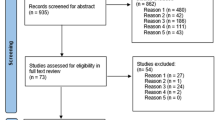

This review paper examines data on black immigrants and healthcare access. We conducted searches on large, pooled scientific and medical databases and search engines including PubMed, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and Project MUSE. Together, these databases house scientific articles from over 150 databases, including PsychInfo, Medline, Science Direct, EBSCO, and Annual Reviews. We used a numerous search terms associated with black immigrant healthcare access including “African,” “Black,” “African immigrants,” “healthcare access,” “foreign-born,” “health,” “quality care,” “US,” “immigration,” “minorities,” and “poor health.” The main goal of the review was to synthesize data available in the US on the quality of healthcare access among black immigrants, to examine the correlates of barriers to healthcare access among black immigrants, and to develop a framework to address these barriers.

Searches were conducted from June 2011 to October 2012 for articles published after the year 2000. In deciding which studies to include in the present article, we focused on those in which black immigrants from Africa and/or the Caribbean constituted the sole research population. In addition, the articles need to have addressed (1) barriers to healthcare and (2) healthcare factors in the US. In total, 1,045 research papers were retrieved using the search terms. However, after we had applied our inclusion/exclusion criteria, only 12 articles remained for our review of the literature on healthcare barriers among African and Caribbean immigrants. The comprehensive nature of our searches reveals the scarcity of studies on black immigrants in the US from Africa and the Caribbean particularly in regard to the barriers they face in accessing health care.

Results

The results of our literature review highlight the factors that determine barriers to healthcare access among black immigrants from Africa and the Caribbean. Such factors include low literacy among black immigrants regarding the US healthcare system, language barriers, stigma regarding illnesses such as HIV/AIDS, and lack of insurance. Table 1 summarizes the literature on the healthcare barriers that black immigrants face and provides each study’s recommendations regarding how to address healthcare access gaps.

Table 1 does not give an exhaustive list of the articles reviewed for the present study. However, the table captures persistent themes in the literature that are pertinent to the study’s focus, i.e., barriers to healthcare access for black immigrants in the US. Our main focus was to summarize the information and suggest a working theoretical framework for future research. The studies are listed according to publication date.

Our Recommendations

In accord with our review, we offer a theoretical model of barriers as indicated in the literature that impact access to care of black immigrants (Fig. 1). The variables (demographic and attitudinal) and structural barriers in the theoretical model (see Fig. 1) interact to form a comprehensive representation showing factors that have a major impact on healthcare access among black immigrant men and women living in the United States. As illustrated, intentions, perceived benefits and health literacy act as moderators on the relationship between demographic variables, attitudinal variables, barriers and healthcare use. Structural barriers, however, can interact in two ways in our model. Structural barriers may interact with moderators (intentions, perceived benefits and health literature) as well as the direct effect of healthcare access and use. The overall model frames the working assumption that black immigrants who have the intentions of accessing healthcare, have perceived benefits of the healthcare use, and have health literacy are more likely to actually access healthcare compared to black immigrants who do not exhibit the moderating factors. Additionally, we offer an applied illustration of how factors from the theoretical model can fit in clinical translation (See Fig. 2). For the applied illustration, factors are split at two conceptual levels—immigrant-level factors and structural-level factors. As shown, immigrant-level factors and corresponding structural barriers are linked, indicating that both conceptual levels must be addressed to overcome and to improve healthcare access and use among black immigrants (Fig. 2).

Theoretical Model Components: Barriers to Healthcare Access for Black Immigrants

Ethnicity

The majority of the studies reviewed indicate that ethnicity was an important correlate of healthcare access [8, 22–25] including access to mental health services [10, 13]. Several studies [6, 21–26] found ethnicity to be a significant factor in determining whether given ethnic groups had a usual source of care. However, one study, Hammond et al. [17] did not find this to be the case. Such inconsistencies suggest that there is a need for further exploration in regard to this demographic and cultural factor.

Gonzalez et al. [21] examined the role of physicians and the effect of ethnicity on screening continuity among black immigrants. According to this study, although the rates for initial testing for the prostate specific antigen (PSA) for Afro-Caribbean do not differ much from US-born, they are less likely than members of other ethnic groups to have subsequent PSA tests. Other factors that predicted the maintenance of PSA screening included having a regular physician, annual physical examinations, and knowledge about the condition. Similarly, Yewoubdar [27] found that immigrants from African and Caribbean ethnic groups were not accustomed to seeking healthcare services. If interventions and policies are to be implemented successfully, they must be specific not only to black immigrant groups but to the diverse segments within those groups. This is a point of some importance that is often overlooked.

We are no longer confined to the borders of our individual countries, and globalization and immigration demand interacting with patients who come from all over the world. And, based on our review of the literature, we recommend that healthcare institutions, physicians, nurses, and other healthcare professionals address issues regarding cultural bias pertaining to the race and/or ethnicity of all patients, particularly in regard to African- and Caribbean-born blacks, as a first and ongoing step in ensuring that the groups under discussion receive adequate health care (see Figs. 1, 2). As indicated in Figs. 1 and 2, in order to address barriers specific to black immigrants, it is essential that healthcare workers be trained to understand and value cultural differences and to apply that understanding to the care they provide their patients and to addressing systemic problems relating to cultural bias in existing healthcare systems.

Language

Among the black immigrants to the US from Africa and the Caribbean, many different countries and nationalities are represented. Moreover, each nationality may include multiple ethnic groups and tribes—each with its own distinct language. As a group, African and Caribbean immigrants speak over 2,100 languages [28]. This multiplicity of ethnicities, cultures, and languages presents a barrier to black immigrant patients [29]. Given that good communication between patients and healthcare providers is essential, the languages and ways in which healthcare information is delivered to these groups must be carefully targeted to specific populations. Likewise, cultural competency on the part of healthcare professionals is also of the utmost importance. Overall, our theoretical models and review of the literature indicate that making educational programs and interpreters available is one way of solving the language and communication barrier that black immigrants face in accessing healthcare services.

Language is the basis of culture [30]. If healthcare access for African- and Caribbean-born immigrants is to be improved, it must be recognized that language training and competency is vital in the healthcare context and that a lack of interpreters for immigrants whose first language is not English can create significant barriers to the delivery of patient care. Even those immigrants who do speak English can be disadvantaged because their accents, lack of information about the US healthcare system, and cultural ideas regarding healthcare and illness can all contribute to miscommunication between themselves and the medical staff who might not understand them. Furthermore, health-related information usually reflects Western culture [27]. This is a genuine concern because language about health information that is centered in only one cultural perspective can result in frustration for both the patients and the medical staff who find it difficult to translate terms and meaning. As a result, language barriers—even among English-speaking immigrants—may hinder patients from accessing healthcare services. Such barriers may mean that immigrants seek healthcare services only as a last resort and thus may negatively affect disease prevention efforts, treatment, and general well-being.

Proper interpretation or translation to ensure the accurate exchange of information may be one key to successful and effective communication and healthcare literacy. In one study, black immigrants indicated that translation services tend to be limited to Spanish, such that African languages are either not adequately covered or are simply unavailable [15]. Another concern is the lack of interpreters, which makes understanding directions and even reading medical literature problematic for those whose first language is not English [21]. The healthcare system, then, has a duty to provide interpreter services (at a minimum) given that it is reasonable to assume this to be a barrier to black immigrants’ ability to access healthcare access.

Legal Status, Discrimination, and Stigmas

Immigrant status constitutes an important barrier to health care for undocumented immigrants. Nonetheless, regardless of specific immigrant status, research has shown that the immigration process itself has some stressor effect on health, which might be correlated with access to quality health care [23]. Another stressor is perceptions on the part of patients that staff members assume that certain groups of immigrants are illegal and discriminate against them based on that assumption. Because of such perceived discrimination and presumed illegal status, black immigrants may underutilize healthcare services [13].

The diversity among black immigrants may also impact their experiences with healthcare services. Therefore, these differences need to be understood and addressed. Black immigrants’ perceptions of the healthcare system determine whether they will access health care in a timely way. For example, Barnett [31] examined African refugees and reported that members of this community are usually hesitant to access HIV testing services because of confidentiality issues regarding legal status. Furthermore, African refugees tend not to trust the healthcare system, such that according to Barnett the healthcare system has the responsibility to communicate that the care provided to US citizens and that provided to refugees and black immigrants are the same.

Black immigrants, with or without legal documentation, are likely to face discrimination based not only on skin color, but also on accent [14, 33], immigrant status and socio-economic status, as well as other factors [32]. Immigrants with accents might face challenges accessing quality health care because of communication problems that undermine efforts to create a good patient–doctor relationship. Thus, discrimination and the treatment associated with it places black immigrants at a disadvantage and may mean they avoid the healthcare system for this reason. Moreover, immigrants with stigmatized ailments such as HIV/AIDS and mental disorders are dissuaded from seeking healthcare services because they fear losing their jobs, being separated from significant others, and in even being deported [11, 27].

Stigma, defined as a label placed on individuals who are perceived as “different,” may also lead to experiences of discrimination and social exclusion [29] and can affect whether and how black immigrants use medical services. For example, the stigma associated with HIV/AIDS discourages black immigrants from being tested for HIV. The effects of this could be that not only do those who need treatment for this disease fail to receive it, but that they are likely to become socially isolated such that they do not receive support services either [34, 35]. Our review indicates that stigmas can be addressed with the collaboration of community members and religious leaders who can lead the way in bridging gaps pertaining to culture, religion, and information between the culture of immigrants and the dominant culture of the country [11]. Similarly, eliminating stigmas related to mental disorders and HIV/AIDS will require that physicians and other medical professionals be trained to approach this issue sensitively with black immigrant populations, especially with family members who to a large extent determine whether the ill person becomes isolated both from their families and the community in general. Jackson et al. [10] have suggested that such training could positively benefit the socialization process of young people, thus creating a generation that is more tolerant and understanding of African People Living With HIV/AIDS (PLWH).

Beliefs and Cultural Competence

Cultural and religious barriers were the main reasons that black immigrants’ delayed access to care, which led to late diagnosis for illnesses such as cancer and HIV [13, 15, 28]. The studies included in our review of the literature almost unanimously agreed that future health studies and in-practice efforts aimed at improving healthcare access for black immigrants must be culturally competent [16, 27, 30]. That is, they must be designed to meet “a set of congruent behaviors, attitudes, and policies that come together in a system, agency, or among professionals that enables effective work in cross-cultural situations” [36].

Competency in regard to the core healing beliefs of African and Caribbean immigrants is particularly important, and is a central component to addressing healthcare barriers (see Fig. 2). Moreover, cultural competency is critical, as it is likely that many members of these groups hold traditional beliefs in regard to medicine that delay their efforts to access Western health care. For example, research indicates that black immigrants may use herbs and other traditional medication and religious practices before consulting with physicians [37–39]. As some such beliefs are cultural in nature, a high level of competency is required to address the health issues of these groups from a Western perspective. Some researchers have suggested that community health workers and medical staff should not attempt to minimize beliefs in traditional medicine, and that instead they should work with black immigrant communities to provide culturally competent community-based care. Such solutions include encouraging collaborative efforts between community health workers and medical staff to identify common beliefs and practices, providing neighborhood medical facilities where the majority of the patients know each other and can become comfortable enough with staff from the community to openly discuss non-Western practices, and training medical staff members to treat all patients whether or not the latter believe in traditional medicine [11]. Hruschka [40] indicates that blacks feel may disrespected by medical staff who disregard their belief in traditional medicine; therefore, efforts must be made to ensure that both the patients and the medical staff are competent to address the medial needs of the former.

Health Literacy

A persistent problem faced by black immigrants in our review was their lack of knowledge about how the US healthcare system works [21]. A key factor in ensuring that immigrants who may be intimidated by a system they have no idea how to navigate is to help them to develop a level of health literacy. One problem mentioned in the reviewed articles suggested a broken system that fails to serve its black immigrant clients because the services offered do not adequately account for cultural considerations. Thus, some studies called for interventions that would be competent to the culture of black immigrants, including educational material for outreach programs. In addition, many black immigrants indicate that a lack of transportation is a primary barrier to accessing health care. Community-based care may be one key way of eliminating this particular barrier, and this is included as theoretical constructs of our offered models, as the services would be in close proximity to the immigrants and the cost of transportation reduced or eliminated.

Summary

In our systematic literature analysis, we sought to synthesize the current knowledge pertaining to unequal access on the part of black immigrants to quality healthcare and the barriers associated with it. Further, unlike many of the preceding studies, we also suggested a framework to address the barriers thus identified.

Findings from the reviewed articles showed that the following factors contributed to the barriers that black immigrants face in accessing health care: demographic variables such as ethnicity, lack of knowledge (lack of health literacy), language barriers/communication, stigma and discrimination (whether real or perceived), and lack of services available in the community. As indicated in our models, services in the community take on issues of language, beliefs and healthcare services. Our research model specifies some recommendations—all of which fit under the overarching principle of cultural competency—that may overcome or reduce the barriers in healthcare access faced by black immigrants. Specifically, we include important factors such as educating patients about the healthcare system, providing interpreters, and incorporating non-Western meaning into educational materials. In both models, culturally competent care includes providing services such as interpreters, incorporating non-Western health meaning into educational materials, and competency in regard to the diversity of languages among black immigrants. In this regard, we encourage interventions that are specific to each ethnic or cultural group. For instance, providing services in some African and Caribbean languages. Understanding how cultural competency is specific to each ethnic group is crucial and can bring about success in implementing programs that aim to reduce and ultimately eliminate barriers to health care access among black immigrants in the US. The importance of cultural competence in realizing the objectives of our respective models cannot be stressed enough. Tackling these barriers to healthcare access is not an easy task because cultural issues are complex. However, a sincere effort based on our recommendations to reduce these access barriers should bring results.

The contributions of this systematic literature review study and models are significant to the growing field of immigrant health research, as the research focusing on the health needs of black immigrants is limited [14, 15]. In most research studies that analyze issues pertaining to healthcare access, black immigrants are lumped together with African-Americans. However, as researchers begin to separate black African immigrants from African-Americans in regard to both data collection and data analysis, researchers are uncovering differences between these two groups in regard to several health outcomes such as factors dependent upon gender and ethnicity. Black immigrants constitute a heterogeneous group that needs to be examined separately from African-Americans and from members of other immigrant groups. In addition to representing the many nationalities and ethnicities of black immigrants, our synthesis highlights the need for healthcare systems to use nuanced language competency for African and Caribbean immigrants. Based on our analysis, it is self-evident that by following the recommendations made herein, healthcare providers will be able to more accurately assess the needs of black immigrants and effect much-needed improvement in the delivery of health care to this group and likewise remove or reduce the barriers this group faces in regard to access.

References

US Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2007.

Passel J, Cohn D. US population projections: 2005–2050. Pew Research Center 2008.

Grieco, E. Race and Hispanic origin of the foreign-born population in the United States: 2007. American Community Survey Reports 2010.

McCabe, K. Caribbean Immigrants in the United States. Migration Policy Institute. 2011.

Becker AE, Arrindell AH, Perloe A, Fay K, Striegel-Moore RH. A qualitative study of perceived social barriers to care for eating disorders: perspectives from ethnically diverse health care consumers. Int J Eat Disord. 2010;43:633–47.

Odedina FT, Dagne G, LaRose-Pierre M, Scrivens J, Emanuel F, Adams A, Pressey S, Odedina O. Within-group differences between native-born and foreign-born black men on prostate cancer risk reduction and early detection practices. J Immigr Minor Health. 2011;13:996–1004. doi:10.1007/s10903-011-9471-8.

Francois F, Elyse′e G, Shah S, Gany F. Colon cancer knowledge and attitudes in an immigrant Haitian community. J Immigr Minor Health. 2009;11:319–25. doi:10.1007/s10903-008-9126-6.

Foley EE. HIV/AIDS and African immigrant women in Philadelphia: structural and cultural barriers to care. AIDS Care. 2005;17(8):1030–43.

Carroll J, Epstein R, Fiscella K, Gipson T, Volpe E, Jean-Pierre P. Caring for Somali women: implications for clinician–patient communication. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;66:337–45.

Jackson JS, Neighbors HW, Torres M, Martin LA, Williams DR, Baser R. Use of mental health services and subjective satisfaction with treatment among black Caribbean immigrants: results from the National Survey of American Life. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):60–7. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2006.088500.

Othieno J. Twin cities care system assessment: process, findings, and recommendations. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007;18:189–213.

Nadeem E, Lange JM, Edge D, Fongwa M, Belin T, Miranda J. Does stigma keep poor young immigrant and U.S.-born black and Latina women from seeking mental health care? Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(12):1547–54.

Williams DR, González HM, Neighbors H, Nesse R, Abelson JM, Sweetman J, Jackson JS. Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean blacks, and Non-Hispanic whites results from the National Survey of American Life. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(3):305–15.

McLaren L. Socioeconomic status and obesity. Epidemiol Rev. 2007;29(1):29–48. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxm001.

McLean C, Campbell C, Cornish F. African-Caribbean interactions with mental health services: experiences and expectations of exclusion as reproductive of health inequalities. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(3):657–69.

Lucas JW, Barr-Anderson DJ, Kington RS. Health status, health insurance and health care utilization patterns of immigrant black men. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(10):1740–7.

Hammond WP, Mohottige D, Chantala K, Hastings JF, Neighbors HW, Snowden L. Determinants of usual source of care disparities among African American and Caribbean black men: findings from the National Survey of American Life. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011;22:157–75.

Kobetz E, Mendoza AD, Barton B, Menard J, Allen G, Pierre L, Diem J, McCoy V, McCoy C. Mammography use among Haitian women in Miami, Florida: an opportunity for intervention. J Immigr Minor Health. 2010;12:418–21. doi:10.1007/s10903-008-9193-8.

Page LC, Goldbaum G, Kent JB, Buskin SE. Access to regular HIV care and disease progression among black African immigrants. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101(12):1230–6.

Gillespie-Johnson M. HIV/AIDS prevention practices among recent immigrant Jamaican Women. Ethn Dis. 2008;18:175–8.

Gonzalez JR, Consedine NS, McKiernan JM, Spencer BA. Barriers to the initiation and maintenance of Prostate Specific Antigen screening in black American and Afro-Caribbean men. J Urol. 2008;180:2403–8. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2008.08.031.

Hajat A, Lucas JB, Kington R. Health outcomes among Hispanic subgroups: data from the National Health Interview Survey, 1992–95. Adv Data. 2000;310:1–14.

Edberg M, Cleary S, Vyas S. A trajectory model for understanding and assessing health disparities in immigrant/refugee communities. J Immigr Minor Health. 2011;13:576–84.

Singer M. AIDS and the health crisis of the urban poor: the perspective of critical medical anthropology. Soc Sci Med. 1994;39(7):931–48.

Starfield B. Pathways of influence on equity in health. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:1355–62.

Griffith DM, Johnson-Lawrence V, Gunter K, Neighbors HW. Race, SES, and obesity among men. Race Soc Probl. 2011;3(4):298–306.

Yewoubdar B. Potential HIV risk behaviors among Ethiopians and Eritreans in the diaspora: a bird’s-eye view. Northeast Afr Stud. 2000;7(2):119–42.

Heine B, Heine B, editors. African languages: An introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2000.

Benoit C, Shumka L, Barlee D. Stigma and the health of vulnerable women research brief 2010, Women’s Health Research Network.

Henslin J. Essentials of sociology: Down to earth approach. Boston: Person/Allyn & Bacon; 2011.

Barnett K. Infectious disease screening for refugees resettled in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:833–41.

Vickerman M. Crosscurrents: West Indian immigrants and race. New York: Oxford University Press; 1999.

Gee EM, Kobayashi KM, Prus SG. Examining the “healthy immigrant effect” in later life: findings from the Canadian Community Health Survey. Can J Aging. 2004;23(Suppl 1):S61–9.

Airhihenbuwa CO, Webster JD. Culture and African contexts of HIV/AIDS prevention, care and support. J Soc Aspects HIV/AIDS Res Alliance. 2007;1(1):4–13.

Corrigan P. How stigma interferes with mental health care. Am Psychol. 2004;59(7):614–25.

Office of Minority Health. Cultural competency. 2005. (http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov).

Purnell JQ, Katz ML, Andersen BL, et al. Social and cultural factors are related to perceived colorectal cancer screening benefits and intentions in African Americans. J Behav Med. 2010;33(1):24–34.

Copeland VC. African Americans: disparities in health care access and utilization. Health Soc Work. 2005;30(3):266–70.

Campinha-Bacote J. A culturally competent model of care for African Americans. Urol Nurs. 2009;29(1):49–54.

Hruschka DJ. Culture as an explanation in population health. Ann Hum Biol. 2009;36(3):235–47.

Conflict of interest

The authors acknowledge that there is no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wafula, E.G., Snipes, S.A. Barriers to Health Care Access Faced by Black Immigrants in the US: Theoretical Considerations and Recommendations. J Immigrant Minority Health 16, 689–698 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-013-9898-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-013-9898-1