Abstract

Understanding the immigrant experience accessing healthcare is essential to improving their health. This qualitative study reports on experiences seeking healthcare for three groups of immigrants in Toronto, Canada: permanent residents, refugee claimants and undocumented immigrants. Undocumented immigrants who are on the Canadian Border Services Agency deportation list are understudied in Canada due to their precarious status. This study will examine the vulnerabilities of this particular subcategory of immigrant and contrast their experiences seeking healthcare with refugee claimants and permanent residents. Twenty-one semi-structured, one-on-one qualitative interviews were conducted with immigrants to identify barriers and facilitators to accessing healthcare. The open structure of the interviews enabled the participants to share their experiences seeking healthcare and other factors that were an integral part of their health. This study utilized a community-based participatory research framework. The study identifies seven sections of results. Among them, immigration status was the single most important factor affecting both an individual’s ability to seek out healthcare and her experiences when trying to access healthcare. The healthcare seeking behaviour of undocumented immigrants was radically distinct from refugee claimants or immigrants with permanent resident status, with undocumented immigrants being at a greater disadvantage than permanent residents and refugee claimants. Language barriers are also noted as an impediment to healthcare access. An individual’s immigration status further complicates their ability to establish relationships with family doctors, access prescriptions and medications and seek out emergency room care. Fear of authorities and the complications caused by the above factors can lead to the most disadvantaged to seek out informal or black market sources of healthcare. This study reaffirmed previous findings that fear of deportation forestalls undocumented immigrants from seeking out healthcare through standard means. The findings bring to light issues not discussed in great depth in the current literature on immigrant health access, the foremost being the immigration status of an individual is a major factor affecting that person’s ability to seek, and experience of, healthcare services. Further, that undocumented immigrants have difficulty gaining access to pharmaceuticals and so may employ unregulated means to obtain medication, often with the assistance of a doctor. Also, there exists two streams of healthcare access for undocumented immigrants—from conventional healthcare facilities but also from informal systems delivered mainly through community-based organizations. Finally, within the umbrella term ‘immigrant’ there appears to be drastically different healthcare utilization patterns and attitudes toward seeking out healthcare between the three subgroups of immigrants addressed by this study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

This study was designed to examine how three groups of immigrants interacted with the healthcare system in Toronto, Canada. The participants were initially recruited through a community-based organization. As per a community-based participatory research approach, the study melded the interests of the community-based organization and the primary researcher. The primary researcher was interested in experiences accessing healthcare and the community-based organization wanted to understand the needs of a subset of their immigrant clients. Although the study was not originally designed to assess differences in immigration status, this factor quickly emerged as the single most important issue affecting healthcare. For the purposes of this paper study participants are divided into three groups: permanent residents, refugee claimants and undocumented immigrants.

This research study addressed two areas of healthcare for the immigrant: access and experience. For access there are three main questions: (1) Who was accessing services, (2) What services were they accessing, and (3) What impact did immigration status have on their experiences accessing those services?

To the primary author’s knowledge this is the first study to have worked with undocumented immigrants who are on the Canadian Border Services Agency deportation list. There are researchers in Canada who work with migrant workers—some of whom lack documents at some point during their stay in Canada. Other Canadian researchers work with persons with ‘precarious status’, a term that includes any individual whose legal status in a country is not stable.

The scientific literature has revealed several barriers to healthcare that immigrants may experience. One such barrier is mistrust of the medical system [1]. For example, a trusting relationship between immigrants and their general practitioners is sometimes compromised by previous negative healthcare encounters experienced by the immigrant in their home country [1]. Distrust of doctors is also propagated by stories circulating within cultural communities [1]. Language barriers between the healthcare provider and patient can result in serious detrimental effects for health outcomes, health status and the quality of care [2, 3]. Bhatia and Wallace [4] explain that language barriers prevent general practitioners from fully understanding the patient’s needs, leading to fewer appropriate referrals to secondary care. Likewise, language barriers make patients less likely to report problems to a physician [4].

In the United States undocumented immigrants are considered to be a vulnerable population at higher risk of disease and injury than both documented immigrants and native citizens [5]. Social and family networks may be the key determinants of access to, and use of, health services among undocumented immigrants living in urban areas [5]. In the United States, undocumented immigrants arrive bearing a disproportionate burden of undiagnosed illness and commonly lack standard immunizations and other basic preventative care [6]. Undocumented immigrants often enter the country under adverse circumstances and live in substandard conditions, factors that exacerbate poor health [6]. Language barriers, lack of knowledge about the healthcare system and fear of detection by authorities are factors that limit the ability of undocumented immigrants to access healthcare [6].

A study in Spain by Perez-Rodriguez et al. [7] found that undocumented immigrants were forced to go directly to the emergency room when they needed general or specialty medical care. Undocumented immigrants are often afraid to go to doctors, fearing that they may be detained or reported to immigration authorities and then deported [8]. Fear of deportation also leads undocumented immigrants to be constantly switching residences in order to evade authorities, a situation which does not promote stability in relationships with healthcare professionals [8].

A literature review published by Magalhaes et al. [9] estimates there are approximately 500,000 undocumented migrants in Canada. This literature review included information up to January 2009. Since then there have been no updated estimates on the number of undocumented migrants in Canada. The term “undocumented migrant” refers to undocumented workers who participate in the Canadian labour force [9]. “Undocumented immigrants” include all people who are undocumented; the term includes migrants/workers but also all other people who lack official status. Therefore, it is not unreasonable to estimate that the number of undocumented immigrants is significantly larger than the number of undocumented migrants. The number of undocumented migrants is also likely higher in 2012 than it was in 2009 when the Magalhaes literature review was published. It is therefore reasonable to expect that there are well over 500,000 undocumented immigrants in Canada.

This research article includes the first qualitative study of undocumented immigrants in Canada, specifically those on the deportation list of Citizenship and Immigration Canada. This study will examine the vulnerabilities of this particular subcategory of immigrant and contrast their experiences seeking healthcare with refugee claimants and permanent residents.

Description of Undocumented Immigrants, Permanent Residents and Refugee Claimants

In this study undocumented immigrants are defined as individuals who have: (A) illegally entered Canada, including persons who were smuggled or trafficked [9], or (B) appealed their denied refugee claim on humanitarian and compassionate grounds and had the appeal rejected and remain in the country after their removal date; or (C) legally entered Canada and (1) did not respect the conditions and terms of their visa, or (2) overstayed their visa, or (3) used fraudulent documentation [9, 10]. Official estimates of the numbers of undocumented immigrants in Canada are not known; some sources suggest an approximate number of half a million people nationally [9].

Refugees can be government assisted or privately sponsored to come to Canada and can also arrive in Canada and seek refugee status upon their arrival. In the case of the participants in this study all individuals applied for refugee status upon their arrival in the country; as such they were refugee claimants and were entitled to the Interim Federal Health Benefit.

Permanent residents have full access to provincial healthcare programs. This study was conducted in Ontario where permanent residents have the Ontario Health Insurance Plan. They are entitled to the same level of healthcare service as Canadian citizens living in Ontario. There is a three-month wait period for Ontario health insurance after a person has arrived in Canada and permanent resident status has been granted during which the permanent resident must acquire private health coverage in order to be medically insured [11].

Detainment and Deportation from Canada

A NOTE ON SOURCES: The formal process for detainment and deportation from Canada is not posted on the website of Citizenship and Immigration Canada nor provided publicly in any form. The process outlined in the following section is compiled from information provided by community-based organizations and advocacy groups in Toronto and interviews with those groups, participants in the study and immigration lawyers. To the primary author’s knowledge this is an accurate account of the deportation process in Canada. |

|

After an individual has attended a meeting at the Greater Toronto Enforcement Centre, they will receive written notification of their removal date from Canada. The date of removal is usually 1 month after the meeting. At this stage the person faces a choice to (a) leave the country, (b) go into hiding, or (c) seek legal support and attempt to overturn the order of removal from Canada. “Go into hiding” was a term used by the participants in this study.

Eight of the nine participants in this study decided to go into hiding upon receiving their removal notice. One individual sought legal advice and involved the media to help make her case against Citizenship and Immigration Canada. Her attempts were unsuccessful and eventually she too went into hiding.

When an individual does not show up at the airport on their removal date, the Canadian Border Services Agency will begin to actively look for them. These actions include going to the individual’s last known residence, phoning them, going to community-based organizations where the individual seeks support, raiding shelters, searching suspected places of employment and seeking out the individual’s children (if applicable).

When someone is detained, they are taken into custody and brought to a deportation facility. They are detained in this facility until a flight to their home country is arranged and then given a seat on a commercial aircraft, usually at the back of the plane. If a flight can be arranged for the individual immediately after detainment, the person will be put on the plane without being kept in a deportation facility.

Immigrants as a Heterogeneous Group

Previous studies have investigated the primary healthcare seeking behaviour of immigrants [3, 12]. It is important to note that ‘immigrants’ in these studies are broadly defined and include several subgroups of immigrants within the same study. This research project treats each immigrant subgroup as a separate entity, so the differences and similarities can be observed across the three groups.

As the results of this study show, undocumented immigrants have vastly different healthcare access than the other two immigrant groups. These differences have enormous implications for the Canadian healthcare system. With estimates that Canada has half-a-million undocumented immigrants, the number of people lacking formal primary healthcare is significant [9].

Conceptual Framework

Community-Based Participatory Research

All research takes place on a continuum, from expert research on one side to community-based participatory research (CBPR) on the other [13]. Expert research is characterized by the control of authority and execution by the academic researcher. By contrast, CBPR is a collaborative process with authority and execution shared between members of the organization under study and the researcher [13]. CBPR has been defined as, “a collaborative process that equitably involves all partners in the research process and recognizes the unique strengths that each brings. CBPR begins with a research topic of importance to the community with the aim of combining knowledge and action for social change to improve community health and eliminate health disparities” [14].

Successful CBPR requires the researcher and the marginalized participants to build a trusting relationship [15]. In the case of this research project, the community-based organization had a pre-existing strong, trusting relationship with all participants in the study. The principle investigator was new to the community and so it was necessary for her to develop a trusting, open relationship with both the community-based organization and the participants. This relationship took over 9 months to build before participant recruitment could begin.

CBPR promotes joint learning, where the research team and the participants learn together. When working with marginalized groups there are often power imbalances that stem from knowledge and social inequalities between the participating members of the study. All study members must be mindful of this and consciously moderate identified power imbalances through methods like joint learning [15, 16]. In the course of this study, joint learning methods were used to inform and improve the research process and the participant experience. During one-on-one interviews the primary researcher told each participant that she was coming to learn from them. This approach aimed to empower the participants and was warmly and openly received. In this study, and CBPR in general, knowledge transfer happens in many directions. The participant should be secure enough in the partnership that they feel able to share fully from their knowledge and experience. It is incumbent upon the researcher to convey to the participant that they understand and value the knowledge being shared.

The importance of addressing inequalities between study members and researchers was previously recognized by Koch et al. [15] who stated, “the researcher should recognize the inherent inequalities between marginalized communities and themselves and attempt to address these by emphasizing knowledge of community members and sharing information, resources and decision making powers”. It should not be assumed that the knowledge and power high ground is solely the domain of the researchers; the researchers, the community organization, the participants or any member of a study can hold valuable knowledge and insight. The researcher needs to be aware of the privilege and power that they hold. The researcher should also be reflexive of where they are situated within the research group.

Working with marginalized persons will always present challenges, as there are tangible power imbalances that demand deliberate and constant negotiation and reflection to ensure equity. They come from difficult situations and must be delicately engaged. Frequent meetings and open channels of communication are vital to ensuring that obstacles can be overcome. Perhaps the most important element of working with marginalized persons is building bonds of trust. The researcher must acknowledge power and privilege and ensure there is value in the project for marginalized persons. Making all participants equal partners in the project can achieve this.

Scope of Research

This study involved a specific subset of immigrants: Spanish-speaking women. The rationalization for this was reached because the community-based organization only worked with women and was keen to have the primary researcher work with their Spanish-speaking group. There were other cultural groups within this organization, including Chinese, Filipino and other language groups, however the community-based organization wanted the researcher to work with the Spanish-speaking group as it was the newest language specific group in their organization. Thus, following CBPR principles of problem identification, this paper focuses on exploring immigrant issues through this sub-population.

This paper does not cover issues of gender and culture, although they are recognized as important and have been explored in other bodies of literature [17–20]. Issues of gender and culture will be the subjects of future papers; instead the focus here is on immigration status and how various statuses shape the experience of accessing healthcare.

Methods

Participants

A total of 21 participants were involved in this study. Women within three immigration categories were recruited: refugee claimants (n = 6), permanent residents (n = 6) and undocumented immigrants (n = 9) outlined in Table 1 (see below).

Study Setting

The study was conducted at a community-based organization in downtown Toronto. This community-based organization is a recognized destination for marginalized persons, including permanent residents, undocumented immigrants and refugees, and offers counseling services with community support workers, hot cooked meals, harm reduction programs and language specific support groups.

Recruitment

The study received ethical approval from the University of Toronto Research Ethics Board. A community support worker recruited all potential participants with the criteria that they were from one of the three immigrant groups and were Spanish-speaking. Forty-three potential participants attended a 2.5 hour orientation session. During this session potential participants learned about the study, requirements for participation, became acquainted with the primary researcher and had an opportunity to ask questions about the study and the researcher. As part of CBPR framework the people attending the orientation session were asked for their thoughts, input on the study and conditions for their participation. Their views about what they wanted out of the study were also solicited. For instance, some of the potential participants at the orientation session wanted the research findings to be shared with “powerful people”. The participants defined “powerful people” to mean: persons in positions of authority who could influence policy and decision-making. The researcher took this, and the other input, into consideration and made her best attempt to accommodate these requests. The Chief Public Health Officer of Canada was invited to attend a presentation to learn about the research. He attended the session and met some of the participants.

Following guidelines set out by Kitto et al. [21], purposeful sampling was used to ensure that the number of people interviewed from each immigration group was approximately equal. Fifteen individuals participated in one-on-one, semi-structured interviews between January and April 2011. Potential participants were told they should contact the community support worker if they were interested in being involved in the research study. The first fifteen women to contact the community support worker were scheduled for interviews, and were ongoing members of the research study. Six additional participants were recruited by initial participants using a snowball sampling technique and were interviewed from September to November 2011. Snowball sampling is used to reach, “difficult-to-access types of participants” [21].

Data Collection

A qualitative research approach was adopted to enhance understanding of the experiences participants encountered when seeking healthcare [21]. Semi-structured one-on-one interviews were informed by best practices outlined by Kvale and Brinkmann [22]. The research team and the community-based organization developed topics for the interview guide following a literature review. The interview guide covered a range of topics including: access to a family doctor and preventive healthcare, barriers and facilitators of healthcare and language and cultural considerations when accessing healthcare. The interview guide was revised as new themes emerged during the interview process [22]. All undocumented immigrants were given the option to create a pseudonym for themselves to help protect their identity. These participants could sign the consent form with their pseudonym or an “x”, depending on their comfort level.

Language Considerations

The primary researcher conducted all interviews. Interviews were conducted in the participant’s language preference of either Spanish or English. Interviews ranged in length from 45 min to 2 h. Spanish interviews were translated by an interpreter from a professional translating agency specialized in working with women who have experienced trauma. The primary researcher’s professional experience and the literature on bilingual individuals in stressful situations both indicate that an otherwise bilingual individual will have difficulty speaking in their second language if describing a stressful or traumatic situation [23, 24]. Javier [23] describes that bilingual individuals shift languages under anxiety-producing conditions as part of their coping mechanism. With the exception of two interviews, the interpreter was present in case any Spanish was spoken during the English interview.

Analysis

One-on-one interviews were taped. The researcher’s questions and the interpreter’s English responses were transcribed verbatim. A native Spanish-speaking professional then checked the transcripts against the audiotapes to ensure accuracy of the initial interpretation. All transcripts were read and the text was coded into units of meaning [22]. Content analysis was used to analyze interviews [25]. Content analysis is defined as, “a research method for the subjective interpretation of the content of text data through the systematic classification process of coding and identifying themes or patterns” [25]. A research triangulation process was employed where the primary researcher, another researcher who was a part of the research team and a researcher external to the group separately coded the transcripts. Ongoing conversations around coding and data indexing ensured coherent and consistent analysis [22]. The re-defining and re-interpretation of codes led to a final coding template that was applied to all interviews. The coded data was grouped into 19 categories and then further divided into subcategories [22].

Results

Description of Results

The seven sections of results, described below, emerged from interviews with the participants.

Topic (a): General Perception of Access to Healthcare

Undocumented Immigrants

Undocumented immigrants were largely unable to access healthcare for either their physical or mental wellbeing. They had difficulty accessing emergency care, primary healthcare and in obtaining medication. Undocumented immigrants feared that seeking healthcare would result in their being reported to the authorities. Personal safety would often be chosen over health.

For those that come through illegal channels they have to sacrifice their health for safety. If I need to get healthcare I risk being reported by the doctor and deported back to Venezuela. My safety has to take precedent over my health. When you are an illegal, those two things are mutually exclusive entities. - Undocumented Immigrant 9 (UI9)

Permanent Residents and Refugee Claimants

Conversely, permanent residents and refugees were generally able to access healthcare for their physical wellbeing. Their experiences in the healthcare system were mixed, but significantly more positive encounters were mentioned during the interview process than for undocumented immigrants.

The first experience was to find a doctor that I could speak in Spanish with. Even though I lived in the U.S. for six years I could not communicate fluently. I found a doctor, I have good experience, his services have been excellent. – Refugee Claimant 2 (RC2)

Topic (b): Family Doctor and Walk-in Clinics

Undocumented Immigrants

For a number of different reasons, many of the undocumented immigrants in this study had never gone to a family doctor or walk-in clinic.

But they (her friends) say that in the walk-in clinics here that you need to wait a really long time and you need to be dying in order to get looked after. - UI7

An additional reason given for never going to walk-in clinics was a fear of the doctor reporting them to the authorities. The emergency room, discussed more fully in topic (d) was used for primary healthcare.

You have no fucking idea what it is like to be me. If I get sick I pop pills and wait. And when I say pills I mean over the counter shit, not prescriptions. If it gets really bad then I have to decide if I think I will die. If I think I will, I go to Emergency. If I don’t then I wait in pain. Why do you ask me about family doctors? Walk-in-clinics? Are you kidding? I have no papers. - UI5

Permanent Residents and Refugee Claimants

In contrast, permanent residents in this study had a doctor for the majority of their time in Canada. Permanent residents rarely used walk-in clinics or emergency rooms. Refugee claimants without a family doctor would often use walk-in clinics as an alternative way of obtaining primary care.

Experiences for refugee claimants and permanent residents with their family doctors were mixed, but most were happy with the care they received. Most permanent residents had been able to find a family doctor who spoke Spanish. Refugee claimants had mixed success with finding a language-specific family doctor. The primary complaint from both refugee claimants and permanent residents was the amount of time they needed to wait for an appointment. The other complaint was they could only discuss one problem with their doctor per visit. Many participants learned about family doctors who spoke Spanish and community organizations that provided services to undocumented immigrants through word of mouth.

The reality is that I don’t know anything about the walk-in clinics. They need to send out information by flyers. They need to tell people what services are available and what they charge. Right now I only access the community centre because I don’t know how the other things work. For example, sometimes the community centre will have a stand where a doctor will come in and take your blood pressure. They should do more of this. That is what I like. - RC6

Topic (c): Prescriptions and Medication

Undocumented Immigrants

Obtaining medication for health problems was challenging for undocumented immigrants. Out-of-pocket payment for medications proved to be impossible for many individuals. This was especially true for those who did not have the finances to cover food and housing expenses. One common solution was to get a doctor to write a prescription under the name of someone with medical insurance. The doctor would usually either comply or would give the patient samples of the required medication.

A lady who I lived with gave me her medication. Then she took me to a doctor using the name of her daughter … I went with her. She talked to the doctor first and told her my situation. She said that I didn’t have documents and that could (the doctor) please see me. And if possible, could (the doctor) put my name in as the name of her daughter. The doctor accepted and wrote the prescription using the girl’s name. - UI6

Permanent Residents and Refugee Claimants

Permanent residents were able to get the prescriptions they required. Refugee claimants could obtain most of their prescriptions. However, some prescriptions were not covered under the Interim Federal Health Benefit and were too expensive to pay for out-of-pocket.

My mom had to take pills once for the brain that were very expensive. Ten tablets were almost $200. I’m not saying that you can’t find a way to pay the money but sometimes people just can’t get the money and you feel like they’re saying, ‘oh ya whatever - die’, you know. - PR5

Topic (d): Emergency Room Care

Undocumented Immigrants

Emergency care was sought only when the medical situation was so troubling or painful that the undocumented immigrants feared for their lives. This is because undocumented immigrants believed that healthcare professionals are likely to report undocumented people to the Canada Border Services Agency. One of the responsibilities of the Canada Border Services Agency is finding and deporting undocumented immigrants from Canada [26]. The undocumented immigrants feared that when they were unable to supply either proof of health insurance or government-issued identification the Canada Border Services Agency would be called.

When I woke up I was in a different room (in the emergency room) and I could see policemen. I was very scared. Thank God nothing happened. I was worried that the police would call border services. - UI4

Permanent Residents and Refugee Claimants

Typically, permanent residents and refugees use the emergency room for emergencies and not for primary care needs. They were not happy with waiting times in the emergency room.

One time I had to go to the hospital for an emergency because my husband had a lot of pain in his chest. We arrived at 5 p.m. one day and still at 5 p.m. the next day he still hadn’t received any medical attention … we didn’t receive any help. We waited so many hours. - PR6

Many were unsuccessful accessing interpreters and had difficulty communicating with hospital staff.

-

Researcher: “Have you been to the emergency room during your time in Canada?”

-

RC1: “Yes, because sometimes I feel pain in the anus…All of the emergency people say it’s because of the stress. I asked for painkillers but he (the doctor) gave me pills instead for depression. I don’t think he understand my problem or what I tell him. No interpreter to help me. He gave me the pills for the wrong thing, but at least they help me relax and sleep.”

Topic (e): Language Barriers

With the exception of two individuals in this study who spoke English fluently, all participants mentioned that language barriers were a major obstacle to seeking healthcare.

It (healthcare) was problematic at the beginning because of the language. I believe it is a big barrier to express what I feel and how I feel it. I have also met rude people at the hospital and they don’t have the patience or the sensitivity to those who are different. There are people who are completely opposed to this but I believe that when they identify you as an immigrant, and you can’t speak the English language, you can immediately see the discrimination. - PR1

Language barriers were also linked to fear because of the inability to communicate with their healthcare provider.

I was terrified that I cannot speak the language in case I was having trouble with my health, I could not communicate well with my doctor. That was my experience when I go to surgery. - RC2

Topic (f): Formal vs. Informal Healthcare

The undocumented immigrants and refugee claimants in this study made frequent mention of Canada having two healthcare systems: One system for Canadians and people with an Ontario Health Insurance Program (OHIP) card to access and a second system used by people without OHIP.

I bet you can get whatever health services you want. You could waltz into a walk-in clinic or the emergency room, anywhere. They would help you. You look like the poster child for Canada. How could they let their poster child with Canadian citizenship and Canadian healthcare insurance get sick? They wouldn’t turn you away or give you second-rate care. I slink away from places that you go. I go where the Blacks and Hispanics go. (Name of community-based organization) thinks I am just like you. I deserve access to the places you can go. – UI5

Undocumented immigrants also spoke of the treatment they receive when they go to a hospital or doctor’s office for healthcare.

I can feel the discrimination when I pull out my papers. I don’t have OHIP. The receptionist’s face will take on a look of disdain. I get worse treatment than the Canadians who have the right card. This is why I go to (name of community-based organization). They don’t judge me because I don’t have OHIP. – RC4

Topic (g): Immigration Status

An individual’s immigration status affected that person’s ability to access healthcare, but it also permeated all other aspects of their lives. Participants spoke about how their immigration status affects their safety and security in the country.

Undocumented Immigrants

Undocumented immigrants would make frequent mention to their lack of status. Participants envisioned what their lives would be like if they had “legal status” in Canada. They imagined legal status would have enormous positive implications for all aspects of their lives. They would be able to walk around the city without scanning for police, a knock on the door would not automatically conjure up visions of terrifying events, like a visit from the Canadian Border Services Agency, and they could receive healthcare, “like all other Canadians”.

-

Researcher: “Is there anything else that you feel is important that we should talk about?”

-

UI7: “It’s just that when one arrives here (in Canada) they get scared and they tend to find work with people like them, who speak Spanish. You are scared because you know you are not allowed to work without documents but you also can’t die of hunger because you have children. So you find ways to do it. Sometimes hiding, sometimes working here or working there. It happens sometimes you work and the boss says, ‘sorry I don’t have money to pay you’. And they don’t pay you. It’s an abuse of people who don’t have documents.”

-

Researcher: “And you can’t report it to the police.”

-

UI7: “Exactly. Yes, they simply say they don’t have the money. They don’t pay you and just disappear. They would never do that to a Canadian. When you have no documents you are the lowest caste. India has the caste system and so does Canada. In India there are the untouchables, in Canada there are people with no documents.”

As members of the lowest caste in Canadian society, undocumented immigrants would compare their lives to other groups in society. They were convinced that their lives would improve if they were able to obtain legal documents giving them right to work, to be paid for their work, the right to access healthcare and many other rights they lacked.

Refugee Claimants

Refugee claimants describe the stress of having to appeal their denied claim on humanitarian and compassionate grounds. For the individual quoted below, her quest for refugee status took her to the United States, where she exhausted all of her options. Before being deported back to her home country, she fled to Canada. Her refugee claim was denied and, as this manuscript went to press, she was still in the process of appealing her failed claim on humanitarian and compassionate grounds.

When you don’t have legal status in a country you are like a prisoner. I am a prisoner because I don’t have any freedom… It is like being a prisoner for nine years. All for my terror of not wanting to be sent to (her home country) because we have the same president of twelve years and he wants to run again next year. He has all of the power. I can’t go back to (her home country). I am very nervous about my appeal being denied on humanitarian reasons. Because I don’t work, because I don’t speak English, what can I do? Sometimes I don’t want to wake up. For real, this is true. If I can do something for my daughter to stay here, protected, I will ask God to send me for death because I am so tired and I cannot sleep. It is no life. I do volunteer job and try to help people. I hope that this stress will not take me before my time because I have a daughter to fight for. But sometimes I do not want to live. I want everything to stop, to finish. There have been so many years. Nine years. – RC2

This individual was a victim of torture in her home country 9 years before this interview. She describes feeling like a prisoner in Canada. Despite being in the process of appealing her refugee claim, she considered herself to be without legal status.

Permanent Residents

Permanent residents reflected back on times in their past when they were struggling for the permanent resident designation. The individual who is quoted below had applied for refugee status in the United States and was denied. After living as undocumented immigrants for several years, she and her family fled to Canada. This interview happened 4 months after she and her family had received their permanent resident papers in Canada.

-

Researcher: “How did life change for you when you got your permanent resident papers?”

-

PR5: “You feel relief. Finally when I see a policeman and don’t have to run and hide. It’s the best feeling in the world. I can walk into a clinic with my head held high. I try not to think about being illegal or the ten-year process for my family to get status. The only thing that matters now is we are all permanent residents. Everything is okay for us now. All the stress leaves. I feel for people who haven’t made it. When you are an illegal you can’t live life. When we were refugee claimants we never knew if we were safe, if our claim will be approved or if we have to run again. Now we are safe. We have been approved, so it is all okay.”

Discussion

This study corroborated many of the findings of previous studies in this area of investigation. We yielded similar findings as studies out of the United States [5, 6] and Spain [1] that fear of deportation acts as a major barrier to the ability of undocumented immigrants to access healthcare. Like Perez-Rodriquez et al. [7], this study found that a side effect of this fear impact was to destabilize the ability of undocumented immigrants to establish a consistent relationship with healthcare providers.

New Contribution to the Literature

This study did generate significant new findings which have concrete future research and policy/practice development implications relating to (a) Immigrants as a Heterogeneous Group, (b) Access to Pharmaceuticals (c) Formal and Informal Healthcare and (d) The Paramount Importance of Immigration Status.

Immigrants as a Heterogeneous Group

As mentioned in the introduction, ‘immigrants’ in research studies are often broadly defined and include several subgroups of immigrants within the same study. This research project makes it clear that within the umbrella term ‘immigrants’ there appears to be radically different healthcare utilization patterns. For instance, most permanent residents in this study had a family doctor and so did not use walk-in-clinics. Undocumented immigrants from the study did not use any form of primary healthcare. They neither had their own family doctor nor did they use walk-in-clinics. This is markedly different than the immigrant with permanent resident status.

Though the number of undocumented immigrants included in this particular study was small, it is nevertheless important to note that the patterns and attitudes in their healthcare seeking behaviour are distinct from refugee claimants or immigrants with permanent resident status. Further research studies can determine if the patterns, attitude and behaviors observed in this study, such as usage of the emergency room for untreated primary healthcare problems, can be more broadly generalized to the undocumented immigrant population.

Access to Pharmaceuticals

The methods by which undocumented immigrants obtain medications and/or prescriptions have not, to the authors’ knowledge, been explored by other studies. Accordingly, though all issues raised in the results section are important, this particular issue is being explored to greater depth here in the discussion section. The literature covers differences between immigrants and non-immigrants in medication-taking behaviour, but does not discuss the ways in which a medically uninsured immigrant secures life saving medication [27, 28].

This study found that uninsured immigrants (undocumented immigrants and in certain cases refugee claimants) would convince the medical health professional to prescribe medication under another individuals name. Refugee claimants can obtain some prescription medication through the Interim Federal Health Benefit, but many medications are not covered under this plan. This finding has potentially significant implications for the medical community. Indeed, the sample size was small, but all of the undocumented immigrants in this study secured medication by either, (1) convincing a medical professional to prescribe under another patient name or, (2) received samples in lieu of a formal prescription. It is therefore not a far stretch to voice concerns that the pharmaceutically uninsured and undocumented communities may be compromised in the way they obtain pharmaceuticals.

Further study is warranted to explore medication obtaining behaviour of the pharmaceutically- uninsured individual and undocumented immigrants. Immigrants with permanent resident status in this study all had additional medical insurance—usually through a spouse or their employer—covering their medication costs. This is not true for all immigrants with permanent resident status. However, a broader discussion of what medications are covered by OHIP is beyond the scope of this paper. Other studies may find that immigrants with permanent resident status, but lacking additional medical insurance, may face difficulty paying out-of-pocket for medication.

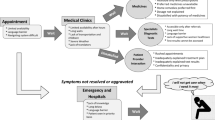

Formal and Informal Healthcare: Informing Future Research

When this study began, the focus of the primary researcher was to understand health access for immigrants within the formal healthcare system. The researcher defined the formal healthcare system to be practitioners and institutions that were established to help the medically insured Canadian public. Included in this list were hospitals, family doctors, walk-in clinics, emergency rooms and other state-established organizations. However, early in the study it quickly became clear to the primary researcher that ‘informal healthcare’, delivered mainly through community-based organizations, was responsible for the vast majority of the care received by undocumented immigrants. The participants in this study became divided into two groups: (1) those that rely primarily on the ‘formal healthcare system’ and, (2) those that access ‘informal healthcare’ for their healthcare needs. Refugee claimants and permanent residents would be classified into one group as both have medical insurance, whether it is a provincial health plan or the Interim Federal Health Benefit. The second group would include undocumented immigrants who are medically uninsured and therefore largely rely on ‘informal healthcare’.

Undocumented immigrants rely almost entirely on community-based organizations, specifically ones with a, “don’t ask don’t tell” policy. These are organizations that do not require any form of identification to access healthcare services. At these community-based organizations a family physician is available on certain days of the week and individuals can either make an appointment to see the doctor or drop into see them. An interesting finding of this study was that the undocumented immigrant views services provided by the community-based organization as separate from the healthcare services offered by the formal healthcare system. While Canada is commonly thought to have a single, universal healthcare system, many participants made reference to the healthcare system being “tiered” or a variation on this theme. This idea of a multi-tiered healthcare system is likely well established amongst those working with undocumented immigrants. It is therefore very important for researchers engaging in projects involving undocumented, uninsured or marginalized populations to note this different viewpoint—that many immigrants view the Canadian healthcare system as tiered. This understanding can help inform study design and the types of information being sought during the research process.

The Paramount Importance of Immigration Status

This research project indicates that a person’s immigration status is the single most important indicator of, (a) whether they can access healthcare and, (b) their experiences seeking healthcare. Clearly, future research with immigrants needs to consider immigration status in research design. Conflating the two groups within sampling designs in future research studies would result in the generation of research findings that could be used to formulate imprecise policies and practices for these disempowered groups. This is particularly true in the case of undocumented immigrants who are remarkably understudied by academics in Canada [9] and internationally [6, 29, 30]. Their situation is distinct from the more commonly studied refugee claimants and immigrants. Undocumented immigrants face unique challenges when seeking healthcare and have very different experiences in the healthcare system.

Limitations: Gender and Language

Findings from this study cannot be generalized to all language-speaking groups though many findings from this study will likely prove to be relevant. The disadvantage of not being able to share findings from different language groups is also an advantage. Working with only Spanish-speaking women unified the group; they all shared the same language and were from similar parts of the world.

Despite the limitations of the sampling design, the results of this study do align with many of the themes found in the immigrant health access literature. The literature on language and immigrants has indicated that language is, indeed, a barrier to accessing healthcare, and deeply affects an individual’s experience in the healthcare system [31–33]. This study supports these findings that language barriers are one of the more significant barriers to be overcome by non-English speaking immigrants.

Relevance for the Community-Based Organization

The community-based organization sought for this study to be done in order to understand the needs of their community. They intend to use the research findings to tailor programs to specifically meet the needs of the Spanish-speaking community. In addition, the community-based organization intends to use the research findings from the study to advocate for the allocation of additional fiscal resources and support.

Lessons Learned: Research with Vulnerable Participants

Community-based participatory research is not an easy road to results. Academic textbooks and publications on community-based participatory research and vulnerable communities will often convey methodology and research findings in a crisp and linear way. While this may be useful for the reader seeking an overview of the research, it is important to note that engaging with very vulnerable communities is an enormously complex process. In these circumstances, research is not crisp and linear; it is blurred and circular. It requires a considerable amount of adaptability, creativity and resilience from all members of the research team.

When working with marginalized people it is of crucial importance to maintain an ongoing evaluation of the project and the effect it is having on the participants, the community and the researcher. Constantly reviewing the project and making revisions based upon lessons learned can be onerous, but the approach also provides great value to all participants. This process helps to enhance the outcomes of the research, the experience of everyone involved and is also a great tool for personal and professional growth for the researcher.

We would encourage future research teams engaging with marginalized communities to consider employing a community-based participatory research framework or a methodology where all team members are equal contributors to the research and outcomes. All members of the research team must be learners; they must be willing to make and learn from mistakes, admit to lack of understanding and re-evaluate their approach. This is especially important when a researcher attempts to engage undocumented immigrants as participants in a research study. Every aspect of the research process must be thought through and then re-evaluated. For instance, going over informed consent once is not enough. For many undocumented immigrant participants in this study the informed consent process was reviewed multiple times. This gives the undocumented immigrant an opportunity to understand the research project and their involvement in great detail. It also gives them time to generate all questions that may be weighting on them about participation. The researcher has to be conscious that the undocumented immigrant may initially feel participating in the study may put them at risk for discovery by the authorities and deportation. By reviewing the research project and informed consent on two, three or even four occasions, the participant may develop respect for the researcher’s patience and explanations. In the case of this research study, the process of gaining informed consent from the undocumented immigrant participants took several months. A relationship of trust is built through this process. This foundation allows for the researcher and participant to engage in research together, research that would otherwise not be possible.

References

Feldmann CT, et al. Afghan refugees and their general practitioners in the Netherlands: to trust or not to trust? Sociol Health Illn. 2007;29(4):515–35.

MacFarlane A, et al. Arranging and negotiating the use of informal interpreters in general practice consultations: experiences of refugees and asylum seekers in the west of Ireland. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(2):210–4.

O’Donnell CA, et al. “They think we’re OK and we know we’re not”. A qualitative study of asylum seekers’ access, knowledge and views to health care in the UK. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:75.

Bhatia R, Wallace P. Experiences of refugees and asylum seekers in general practice: a qualitative study. BMC Family Pract. 2007;8:48.

Nandi A, et al. Access to and use of health services among undocumented Mexican immigrants in a US urban area. Am J Pub Health. 2008;98(11):2011–20.

Kullgren JT. Restrictions on undocumented immigrants’ access to health services: the public health implications of welfare reform. Am J Pub Health. 2003;93(10):1630–3.

Perez-Rodriguez MM, et al. Demand for psychiatric emergency services and immigration. Findings in a Spanish hospital during the year 2003. Eur J Pub Health. 2006;16(4):383–7.

MigHealthNet. Refugees and asylum seekers - Entitlement to care & News on the Entitlement of Failed Asylum Seekers and Undocumented Migrants to Health Care Services. 2011. Available from: http://mighealth.net/uk/index.php.

Magalhaes L, Carrasco C, Gastaldo D. Undocumented migrants in Canada: a scope literature review on health, access to services, and working conditions. J Immigr Minor Health. 2010;12(1):132–51.

Papademetriou DG. The global struggle with illegal migration: no end in sight. Washington: Migration Policy Institute; 2005.

Ontario Government. Immigrating to Ontario, Healthcare Commonly Asked Questions. 2012. Available from: http://www.ontarioimmigration.ca/en/questions/OI_QUESTIONS_COMMON.html#_Health5.

Hargreaves S, et al. Impact on and use of health services by international migrants: questionnaire survey of inner city. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:153.

Greenwood DJ, Whyte WF, Harkavy I. Participatory action research as a process and as a goal. Hum Relat. 1993;46(175).

Minkler M, et al. Community-based participatory research: implications for public health funding. Am J Pub Health. 2003;93(8):4.

Koch T, Kralik D. Participatory action research in health care. Hoboken: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2006.

MacFarlane A, Dzebisova Z, Karapish D. Arranging and negotiating the use of informal interpretaters in general practice consultations: experience of refugees and asylum seekers in the west of Ireland. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69:210–4.

Costantino G, Malgady RG, Primavera LH. Congruence between culturally competent treatment and cultural needs of older Latinos. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(5):941–9.

Cabassa LJ, Zayas LH. Latino immigrants’ intentions to seek depression care. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2007;77(2):231–42.

Green EH, et al. Pap smear rates among Haitian immigrant women in eastern Massachusetts. Pub Health Rep. 2005;120(2):133–9.

Carroll J, et al. Caring for Somali women: implications for clinician-patient communication. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;66(3):337–45.

Kitto SC, Chesters J, Grbich C. Quality in qualitative research. Med J Aust. 2008;188:243–6.

Kvale S, Brinkmann S. Interviews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing. 2nd ed. California: SAGE Publications; 2009.

Javier RA. Linguistic considerations in the treatment of bilinguals. Psychoanal Psychol. 1989;6(1):87–96.

Javier RA. The Bilingual mind: thinking, feeling and speaking in two languages (cognition and language: a series in psycholinguistics). Queens: Springer Science+Business Media; 2007.

Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277.

Canada Border Services Agency. The Canada Border Services Agency. 2011. Available from: http://www.cbsa-asfc.gc.ca/menu-eng.html.

Rue M, et al. Differences in pharmaceutical consumption and expenses between immigrant and Spanish-born populations in Lleida, (Spain): a 6-months prospective observational study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:35.

Reijneveld SA. Reported health, lifestyles, and use of health care of first generation immigrants in The Netherlands: do socioeconomic factors explain their adverse position? J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(5):298–304.

Reijneveld S, et al. Contacts of general practitioners with illegal immigrants (Netherlands). Scand J Pub Health. 2001;29(4):308–13.

Sullivan TM, Sophia N, Maung C. Using evidence to improve reproductive health quality along the Thailand-Burma border. Disasters. 2004;28(3):255–68.

MacFarlane A, et al. Responses to language barriers in consultations with refugees and asylum seekers: a telephone survey of Irish general practitioners. BMC Family Pract. 2008;9:68.

Harmsen JAM, et al. Patients’ evaluation of quality of care in general practice: what are the cultural and linguistic barriers? Patient Educ Couns. 2008;72(1):155–62.

Ingram J. The health needs of the Somali community in Bristol. Community Practitioner. 2009;82(12):26–9.

Acknowledgments

I offer my deepest thanks to all of the participants in this study. I am indebted to your strength, resilience and willingness to share openly in order that others can learn from your experiences. I thank the community-based organization for welcoming me into their confidence and allowing this research study to take place. Thank you to Dr. Thomas Stewart and Mr. Joseph Mapa for their support of this study. Angela Robertson played a pivotal role in this research study and I am grateful for her on-going guidance through every stage. I am also indebted to the reviewer for the Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health who critiqued this manuscript, your suggestions significantly improved the caliber of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

RC conducted all one-on-one interviews with study participants and worked with the community-based organization to plan the research study. BH, DF and SK assisted RC with the study and interview design. RC and BH coded the transcripts. SK guided the study framework and the method of analyzing data. RC wrote the manuscript, with input and comments from all authors. AK was responsible for helping RC shape the manuscript into a comprehensive document. All authors read and approved the final version.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Campbell, R.M., Klei, A.G., Hodges, B.D. et al. A Comparison of Health Access Between Permanent Residents, Undocumented Immigrants and Refugee Claimants in Toronto, Canada. J Immigrant Minority Health 16, 165–176 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-012-9740-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-012-9740-1