Abstract

Chinese parents are highly renowned for their enthusiasm in children’s education and for extremely high expectations for their children’s scholastic performance. Using the China Family Panel Studies from 2010 to 2014, this paper examines the effects of children’s academic performance on their parents’ life satisfaction in China. We find that a one-unit rise in the class ranking of the child increases the parent’s life satisfaction score by 3.4 percentage points. Conversely, parents’ excessive educational involvement can have an adverse impact on their life satisfaction. The significant positive relationship between children’s academic performance and parents’ life satisfaction was, though, apparent only for middle-income, urban and single-child families, and only in provinces that are highly influenced by Confucianism. Our study also provides a partial socio-economic insight into Chinese parents’ obsession with their children’s education, and offers some important implications for policy makers in China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Chinese parents’ enthusiasm for their children’s education has been well documented, as have their extremely high expectations for their children’s academic school performance (Mok et al. 2009; Sharma 2013; Zheng 2017). This phenomenon is in fact widespread across East Asia and has become known as “education fever.”Footnote 1 It reflects a national parental obsession with their children’s educational attainment. It is common for most Chinese parents to spend huge sums on sending their children to private tutoring classes and extracurricular educational training camps, and even to purchase expensive houses just because they are near particular key schoolsFootnote 2 (Feng and Lu 2013; Zhou and Wang 2015). Furthermore, wealthier Chinese parents are willing to invest a large amount of their fortune to send their children to an English-speaking country for a better quality of education (Bodycott 2009; Hvistendahl 2009). This led us to believe that Chinese parents’ life satisfaction might be hugely affected by their children’s academic performance, and this will be our central research question.

Our research falls into the broad category of studies on parent–child interactions. This stream of literature has looked at the effects of parenthood itself on a person’s happiness, as well as the effect of children’s sex and age on parental happiness (Angeles 2010; Hansen 2012; Margolis and Myrskyla 2016; Nelson et al. 2013; Nomaguchi 2012; Pushkar et al. 2014). Whether children’s academic performance can contribute to their parents’ well-being has scarcely been researched.

Other studies of children’s academic performance have looked at whether it influences parental expectations of their educational achievements, as well as the parents’ investment in their children’s education. Goldenberg et al. (2001) found that children’s good school performance increased their parents’ expectations, and Phalet and Schönpflug (2001) found that better educational opportunities for children in higher school tracks led to more parental emphasis on educational success. Gelber and Isen (2013) suggest that those government pre-school educational programs that aim to increase children’s cognitive test scores tend to increase parental involvement in their children’s educational activities. Similar studies to ours have shed light on children’s academic performance and parents’ satisfaction; however, they focus either on a relation between school-level performance and parents’ satisfaction towards schools (Charbonneau and Van Ryzin 2012; Gibbons and Silva 2011) or on ethnic differences in parental satisfaction towards their children among mothers with college-enrolled children (Chang and Greenberger 2012). These two measures—namely parents’ satisfaction with school environment and with their parenting experience with children—are not perceptions about general life satisfaction. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to examine the relationship between children’s academic performance and parents’ life satisfaction.

To test the relationship between children’s academic performance and parents’ life satisfaction, we use panel data from a national longitudinal survey, the China Family Panel Studies (hereafter, CFPS) from 2010 to 2014. A fixed effects model is used to control for individual fixed effects in our data. From the survey questions, we use students’ ranking in class as a measure for their academic performance, and parents’ life satisfaction scores, which can range from 1 (not satisfied at all) to 5 (very satisfied).

Our baseline model for the whole sample suggests that children’s class rankings are positively correlated with parents’ life satisfaction. Specifically, a one-unit increase in class ranking increases parents’ life satisfaction score by 3.4 percentage points. Given the large sample size, we are able to analyze possible heterogeneity effects present in household income, place of residence (urban/rural), family size and influence of Confucianism. We find that the aforementioned positive relationship between children’s academic performance and parents’ life satisfaction is valid for only middle-income, urban and single-child families, and only in provinces that are highly influenced by Confucianism. We conduct further regression analyses and show that parents’ financial support for children’s extra-class tutoring is an important factor that can adversely affect parents’ life satisfaction.

Our contributions are threefold. First, this study fills a gap in the literature on happiness economics by examining the impact of children’s academic performance on parents’ life satisfaction, and so offers a novel insight from an intergenerational perspective. Previous studies on people’s life satisfaction mainly focused on how socio-economic factors such as income, income inequality, social interaction, economic development, level of democracy, or quality of government services affect people’s well-being (Ott 2010; Reyes-García et al. 2019; Wu and Zhu 2016; Yuan 2016). The impact of personal characteristics like age, sex, income, and education on life satisfaction has also been widely examined in the literature.Footnote 3

Second, our results suggest that only middle-class parents are significantly affected by their children’s academic performance. Similarly, Kim and Bang (2017) and Lareau (2003) argue that parents’ perspectives on child education differ with social class, and that middle-class parents strive to secure their social status via the educational capital of their children. We find that families with the lowest and highest incomes have less aspiration in relation to their children’s academic performance and are less motivated to try to improve their children’s class ranking. Our study therefore provides novel evidence on the reasons and mechanisms behind the prevailing middle-class anxiety in China associated with their children’s education.

Finally, this study has important implications for policy makers in Asian countries that are experiencing education fever. China is a developing economy that is experiencing rapid social transformation, characterized by increasing marketization, massive economic growth, and huge population shifts from rural to urban areas. Increasing investment in what has been termed “shadow education”, which serves to supplement formal schooling in China, has been a source of government concern, as this informal education may undermine the government’s aim to have equality in education. There are also concerns about the domestic financial burden that shadow education represents. Regulations are needed to address these concerns. Moreover, it might be necessary to persuade middle-class families that a more rational investment in their children’s education would be through the allocation of greater public resources (i.e. tax-raised finance) to state-sector education, and hence to the government’s aim of equality of opportunities. It is also of great importance to encourage and help lower-class families to engage more in their children’s education, in order to increase social class mobility. Our study also offers a unique insight into the effects of the “one child policy” in China.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 sets out the cultural and political background to Chinese parents’ emphasis on educational achievement; Sect. 3 describes the data and methodology; Sect. 4 presents our findings; Sect. 5 describes the robust checks; and Sect. 6 concludes.

2 Background: Why Do Chinese Parents Have an Education Fever?

Across the world, most parents greatly value their children’s education and are willing to invest in it to some degree; however, Chinese parents’ enthusiasm for their children’s good academic performance seems to lie at an international extreme, at least in terms of their financial investment. Some of the reasons behind this obsession relate to Chinese labor market reform, inequalities in educational resources, intensified competition due to the marketization of education, and traditional Chinese culture, which emphasizes success in education.

2.1 Labor Market Reform in China

The long-standing Chinese household registration system (hukou) has formed an institutional framework that hinders population migration and labor mobility in China (Bosker et al. 2012; Song 2014). At one time, this system effectively controlled the rural population from migrating to urban areas. Hence, those who lived in urban areas faced less competition and some urban residents enjoyed jobs with a lifetime tenure; this situation has been termed the “iron rice bowl” (Chan 2010; Cheng and Selden 1994; Cook 2002). However, the household registration system was reformed in 1984, and by 2015 the total number of internal migrants in China had reached 247 million. These migrant workers increased job market competition dramatically within urban areas, through the supply of low-cost labor (Li et al. 2012). Furthermore, after China’s transformation into a market-oriented economy, a large number of state-owned enterprises went bankrupt and laid off workers (Cao et al. 1999).

In the new context described above, education has become increasingly important due to intense labor market competition, and Chinese parents believe that a good education is the key to getting a good job and a high income for their children (Li et al. 2012). Especially, after China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, the Chinese labor market has been challenged to become more competitive within the global environment. There has been increasing demand for skilled labor, and this has raised parents’ emphasis on education to even higher levels (Ding et al. 2009b). It becomes more necessary for urban parents to invest in education since they expect their children to receive better education to get more decent jobs, whereas children in rural areas consider education as the best way to change their fate.Footnote 4 Therefore, our study aims to examine whether parents’ life satisfaction is significantly affected by their children’s academic performance, given the ever increasing competitiveness of the Chinese labor market.

2.2 The Elite Education System and the Marketization of Education in China

Since 1978, we have witnessed two major reforms of the Chinese education system. First, there has been a transformation from a popular education model to an elite education model characterized by a key school system (Wu 2013).

The Chinese government now classifies schools as key or non-key, and key schools are further divided into national, provincial, municipal and district (county) “priorities” (Wu 2013, 2017). In order to maintain a high admission rate to good universities, middle and high schools select outstanding students for their key classes (“Rocket Classes” or “Experimental Classes”). Parents are naturally keen to have their children selected for these classes, and this has led to the rapid growth of after-school education. “Shadow education” in China includes private tutoring classes, supplementary tutoring of curricular subjects, and extracurricular educational activities. Students in compulsory education are forced to attend after-school tutorials. Shadow education effectively extends the competition in academic performance from within the school campus to outside that campus.

The second transition in the Chinese education system has been from a planned funding model to a market-oriented funding one. The central government provides funding for key schools, while most other schools are financed by local government (Lin and Zhang 2006). This has led to an increase in regional disparities in education. Rich and urban areas tend to have more educational resources and opportunities than poor and rural ones (Dello-Iacovo 2009). In addition, a part of education funding is provided by schools themselves. Schools are able to charge tuition fees and claim expenses, but this makes it more difficult for some families to afford formal education (Hannum and Adams 2009). The marketization of education has led to increasingly unequal educational opportunities. Therefore, our study aims to examine the impact of children’s academic performance on parents’ life satisfaction across different income groups.

2.3 Confucianism and the Civil Service Examination

Confucianism greatly values academic success (Lam et al. 2002; Zhou and Wang 2015). Well-educated people gain high social status and reputation in Chinese society. This can be seen in many statements of Confucian philosophy, for example “to be a scholar is to be at the top of society”. Furthermore, according to Confucian philosophy, parents are expected to nurture their children and children are expected to fulfill their parents’ expectations (Leung and Shek 2011).

The formal civil service examination system known as Keju, in place since the Sui Tang Dynasty, had further strengthened the emphasis on education. Every male, in theory, was given an opportunity to be recruited for civil positions through the imperial examination. The exam was the prime opportunity for Chinese males to advance themselves socially, fostering a consensus that “a good scholar can become a good official”. With Confucian philosophy deeply planted in Chinese culture, there is a strong desire to gain honor, prestige, and social advancement through education. It is hence reasonable to believe that Chinese parents’ life satisfaction is affected by their children’s academic achievements.

3 Data Description and Methodology

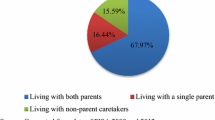

Our study is based on the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) 2010–2014. The CFPS form the largest nationwide comprehensive longitudinal survey in China, which has been conducted in 2010, 2012, and 2014 by Peking University and the Institute of Social Science Survey of Peking University. The CFPS adopts an implicit stratification probability sampling method and covers 162 counties in 25 provinces of China, providing detailed information on economic activities, education, family relationship dynamics, population migration, health and subjective well-being (SWB). We focus on students who are attending primary, middle or high school. We identify parents and children with their ID codes from the 2010, 2012, and 2014 surveys and generate panel data, which allows us to examine the relationship between children’s academic performance and parents’ life satisfaction by using a fixed effects model.

3.1 Dependent Variables

Life satisfaction and happiness are two important measures of subjective well-being, with different emphases. Life satisfaction is considered as a cognitive overall evaluation of subjective well-being, whereas happiness is more susceptible to perceptions and affective feelings. Since our study looked at well-being that is more cognitive and is less affected by emotions, we use life satisfaction as our main dependent variable and happiness in the robustness checks. The three waves of surveys (2010, 2012, and 2014) all contain a question on life satisfaction: “Overall, how satisfied are you with your life?” The answer is given on a scale from 1 (not satisfied at all) to 5 (very satisfied) in all surveys. As to happiness, the survey in 2010 and 2014 asked each participant “How happy do you think you are?”, and the answer was on a scale from 1 (very unhappy) to 5 (very happy) in CFPS 2010, and on a scale from 0 (lowest) to 10 (highest)Footnote 5 in CFPS 2014.

3.2 Independent Variables

Our study draws on two measures of academic performance: children’s academic ranking in class (Ranking) and parents’ evaluation of their child’s performance in Chinese language and math (Language evaluation, Math evaluation). The former is the main indicator and the latter is used as a robustness check. In addition, we control for child-level, parent-level, and regional-level characteristics to avoid potential biases caused by omitted variables.

3.2.1 Children’s Academic Performance

It should be noted that the ranking in class is an objective measure. Students above 10 years old in CFPS 2012 and 2014 were asked the question “In the last exam (midterm or final exam), what was your rank in the class?”, with the following response categories: 1 (top 10%), 2 (top 11–25%), 3 (top 26–50%), 4 (top 51–75%), 5 (bottom 24%). CFPS 2010 asked students to report their class rankings for Chinese language and math, rather than their overall class rankings. The questions were phrased as “In the last exam (midterm or final exam), what was your rank for language in the class?” and “In the last exam (midterm or final exam), what was your rank for math in the class?”, and the answers should be the specific ranking other than the previous categories seen in other surveys. In order to be consistent, we combine this class ranking number with class size, and construct a variable for class ranking that is comparable to that for CFPS 2012 and 2014.Footnote 6 Finally, we reverse the scale so that the higher the value, the better the academic performance is.

We also use the parents’ evaluation of the child’s academic performance in Chinese language and math (Language evaluation, Math evaluation) as robustness checks. All three rounds of CFPS asked parents of children under 16 years of age: “As far as you know, what was the child’s average grade in Chinese language/math last semester?”. The four options were: Excellent/Good/Average/Poor.

3.2.2 Child-level Characteristics Variables

Given that children’s characteristics might affect their academic performance and their parents’ life satisfaction, we control for these. Following the literature, we control for three child-level characteristics: health status (Health), an interaction term of gender and health status (Health × Gender), and number of children in the family (Sibling size).

First, healthier children are expected to perform better and to increase their parents’ life satisfaction (Ding et al. 2009a; Seirawan et al. 2012). Second, studies have found that some parents show a preference for sons, and a difference in the treatment of boys and girls in terms of educational investment exists in some cultures (Connelly and Zheng 2003; Hannum and Adams 2007). Since the gender of the child is time-invariant, we add an interaction term of the health dummy and the gender dummy (Health × Gender) to control for the effect of gender. Third, the number of children can influence the happiness of parents (Angeles 2010). Furthermore, there is a potential tradeoff between quantity and quality in terms of educational investment in children (Lu and Treiman 2008). Thus, we control for the number of children (Sibling size) in the family.

We also control for several other educational characteristics, including whether the child attends a key school (Key school), and whether the child is in a key class (Key class). This is because the competence of children in primary school and the advantages or disadvantages accumulated in prior educational tracks are believed to have an impact on opportunities to enter key schools or key classes, which are associated with children’s academic performance (Wu 2017).

3.2.3 Parent-level Characteristics

We also control for parent-level characteristics, including parents’ income (Ln_income, Relative income), marriage, health, and employment status (Marry, Health, Employ), an interaction term between health evaluation and education level (Health × Education level) and social interaction (Ln_comm).

Income is a significant factor in a person’s life satisfaction (Clark et al. 2008; Easterlin 2001). It is also highly correlated with children’s academic performance (Mayer 1997). In this study, we control for the logarithm of annual household per capita income (Ln_income) and self-rated income status (Relative income) provided in the surveys. In addition, a stable marriage is found to be positively correlated with parents’ life satisfaction (Diener et al. 2000). Health status is also controlled for, since good physical health is found to increase happiness in general. Furthermore, parents’ health status may affect family finances, and hence parental investment in the children’s education (Hannum and Adams 2009). We control for marriage and health status of the parents. We also control for the interaction of health and education (Health × Education level), as the parents’ level of education may be related to their life satisfaction. We also include employment status (Employ) in the regression, since unemployment has a large negative impact on happiness and might affect children’s academic performance (Lucas-Thompson et al. 2010). Social interaction/ties are shown to greatly influence life satisfaction (Greyling and Tregenna 2017;Lei et al. 2015;Posel and Casale 2011; Yuan 2016). Larsen et al. (2006) point out that mobile phones and internet are critical for modern people to establish and maintain their social network. Accordingly, we measure social interaction as the expenditure on communication, including service fees for using telephones, mobile phones, postal mail and the internet (Ln_comm).

3.2.4 Regional Characteristics

In addition to micro-level control variables, regional characteristics are believed to have an influence on parents’ subjective well-being. A concern we have is that children’s academic performance might be correlated with some regional determinants of parents’ life satisfaction. In other words, regional economic performance and public spending are expected to be associated with parents’ life satisfaction, and they also play a role in regional educational investment (Diener 2000; Ram 2009). Therefore, we control for these effects by adding the logarithm of province-level per capita GDP (GDP), the percentage of the total population living in urban areas (Urbanization), and the share of spending on science, education and social security in total public expenditure (Expenditure share) into our regression.

3.3 Empirical Methods

We estimate the effect of children’s academic performance on parents’ life satisfaction using the following equation:Footnote 7

The dependent variable, \(LF_{ijt}\), is the life satisfaction score of parent i in county j at time t. The key variable, \(Ranking_{ijt}\), is the academic ranking in class of child i in county j at time t. \(P_{ijt}\) is a set of variables that measure parents’ characteristics, including income level, marital, health and employment status, social interaction, and interaction terms of health status and education level. \(C_{ijt}\) is a set of variables that covers children’s characteristics, including health status, interaction terms of gender and health status, number of children, and key school and key class dummies. \(R_{ijt}\) is a set of provincial characteristics, including the logarithm of per capita GDP, urbanization, and the ratio of science, education, and social security expenditure to total public expenditure. \(\lambda_{i}\) denotes individual fixed effects; \(\delta_{j}\) represents county fixed effects; \(\eta_{t}\) indicates year fixed effects; \(\varepsilon_{ijt}\) is the error term.

The main coefficient of interest here is \(\alpha\). It can be interpreted as the effect of children’s ranking in class on the parents’ life satisfaction score. It should be noted that children’s ranking in class and parents’ life satisfaction scores are drawn from the same survey. This is reasonable, given that students were asked about their mid-term or final-term exam results and parents have had several months to collect information about their children’s academic performance and respond accordingly in the survey. We report descriptive statistics in Table 1, and the definitions of key variables in Table 8 in “Appendix”.

Before undertaking the quantitative analysis, we plot children’s class ranking and parent’s life satisfaction to get a general picture of their relationship. As shown in Fig. 1, there is a significant positive correlation between children’s class ranking and parents’ life satisfaction. We also calculate the within-individual mean deviation of children’s ranking in class and parents’ life satisfaction. In the bivariate plot, we see a positive relationship as we expected, as shown in Fig. 2. Based on this descriptive evidence from bivariate plots, further quantitative analysis is undertaken to verify the relationship between children’s academic performance and parents’ life satisfaction.

4 Results

In this section, we empirically test the relationship between children’s academic performance and parents’ life satisfaction. Baseline regression results based on the whole sample are provided along with results on heterogeneity effects and a further investigation of factors that emphasize parents’ involvement in education.

4.1 Baseline Model

Table 2 provides baseline regression results from Eq. (1), and all results are estimated with fixed effects. Table 2 reports our estimates for various specifications. In column 1, we include ranking in class, individual fixed effects and year dummies. As reported in column 1, the coefficient on Ranking is positive and significant, suggesting that children’s ranking in class has a positive influence on parents’ life satisfaction.

However, children’s academic performance might be correlated with other confounding factors associated with parents’ life satisfaction, hence leading to biased estimates. To address this concern, we repeat the estimation in column 2 except that we include a vector of time-varying individual control variables. The control variables are: Ln_income, Relative income, parent-level characteristics, and child-level characteristics. The results are consistent with the baseline results.

Column 3 of Table 2 reports the regression results after allowing for a set of provincial macro-characteristics. Again, the results are consistent with the baseline regression, with little change in the magnitude and significance of the key coefficients. In column 4, we present the regression results after including time-varying controls plus county fixed effects, and the coefficient on Ranking is 0.034. This means that a one-unit increase in ranking increases parents’ life satisfaction score by 3.4 percentage points.

As shown in column 4 of Table 2, the coefficient on the Relative income variable is 0.1688, indicating that a one-unit increase in self-rated relative income status raises life satisfaction by 16.88 percentage points. This is consistent with conclusions reported in the happiness economics literature (e.g. Easterlin et al. 2010) that relative income is crucial to people’s happiness.

4.2 Heterogeneity Effects

Parents from different families can react differently to children’s educational achievements. Hence, we examine whether the effect of children’s academic performance on parents’ life satisfaction is heterogeneous across different types of families. We categorize families into different groups according to their income, residence (urban/rural), number of children (sibling size) and the influence of Confucianism (number of successful candidates to total population in the imperial examination at provincial level).

4.2.1 Household Income

First, we test for heterogeneity effects in different household income and social status (relative income) groups. The results are shown in Table 3, Panel A. For brevity, only key variables are reported here. In general, our results show that the positive effect of children’s academic performance on parents’ life satisfaction is significant in middle-income or middle-status groups, whereas we find no significant impact of children’s academic performance in other groups. Columns 1–3 present results for the three income groups.Footnote 8

For the low-income families (column 1) and high-income families (column 3), children’s academic performance is not statistically significantly correlated with the life satisfaction of parents. However, the effect is significant in the middle-income group, with a positive coefficient of 0.08, indicating that a one-unit increase in children’s class ranking increases parents’ life satisfaction scores by 8 percentage points (column 2). In columns 4–6, we split the sample into three groups based on self-rated social status on a scale from 1 (low) to 5 (high): low social status (1 or 2), middle social status (3), and high social status (4 or 5). Parents who consider themselves to be of middle social status are likely to have a 4.99 percentage point increase in life satisfaction from a one-unit improvement in their child’s ranking in class. For the lower self-rated social status group and the higher self-rated social status group, the effect is not significant. These results suggest that the impact of children’s academic performance on parents’ life satisfaction depends on parents’ income and social status.

People from different income groups (low, middle, high) tend to differ in their perceptions of their children’s chances of educational success according to costs and opportunity structures, and the relative benefits and costs of achieving good grades vary across households with different income levels (Oketch et al. 2012). Several reasons are given here (relating to Chinese culture and relevant theories) to explain the heterogeneity effect embedded in household income, especially why the impact only exists in middle-income families.

In general, parents in low-income families tend to be uncertain or pessimistic about whether investment in their children’s education will pay off in the future (Andreoni and Sprenger 2012; Kalil 2015). Furthermore, low-income parents tend to struggle with daily financial constraints, leaving them with little time in which to focus on their children’s education (Mullainathan and Shafir 2013). This is consistent with studies led by Kim (2013), who found that Korean parents with less education and lower socio-economic status are less motivated to improve their children’s academic performance. Studies on US parents by MacLeod (2018), Portes and Rumbaut (2001) and Ogbu (1987) show that parents’ expectations of their children’s academic success can be adversely affected if they have illegal immigrant status, or low-income jobs, or if they are Hispanic and in a state of poverty. Parents in low-income families are at a disadvantage in providing good education and are often less interested in their children’s education.

Parents in high-income families show a similarly low degree of interest in their children’s ranking. This is not surprising, since they have more resources and options to guarantee college admission for their children, other than via formal education. For example, children from high-income families have more and earlier access to school selection opportunities where there are lower entry requirements (in terms of academic performance) for students with skills in the arts or sports. The tuition fees for children to acquire such skills represent a barrier for low-income children. High-income families are also able to send their children to study abroad, beyond the fierce competition in the national test (GaoKao). Therefore, high-income parents do not have to pay particular attention to their children’s class ranking, which in turn therefore has little impact on the parent’s life satisfaction.

In contrast, middle-income parents are significantly affected by their children’s academic performance, because their children will have to rely on their educational attainment to guarantee their career success. Indeed, most middle-income parents have established their own career and social status through education. Hence, they believe that their children’s social status will depend on their education. This, to some extent, explains why middle-income parents are obsessed with their children’s academic performance. In addition, compared with low-income families, middle-income ones are more able to financially support their children’s education; however, they do not have the scale of resources that can be offered by high-income families. Therefore, middle-income families are more heavily involved in the competition for educational resources and care more about their children’s class ranking. As a result, children’s academic performance has a greater effect on their parents’ life satisfaction compared with parents in low- and high-income families. It is of concern that this competition for educational resources, and the desire for children to achieve a superior social status, has placed middle-income parents in a mentally vulnerable condition and this forms a part of the so-called “middle class anxiety” in China.

4.2.2 Household Residence

Another potential source of heterogeneity that we investigate is whether the effect of children’s academic performance differs among rural and urban parents. Results are reported in Table 3, Panel B. In columns 1 and 2, we split the sample into two groups by residential status. In general, parents in urban areas have more than a 6-percentage point improvement in their life satisfaction scores in response to one-unit increase in their children’s ranking in class, whereas for those who live in rural areas the figure is just over 0.5 of a percentage point, and the coefficient is not significant.

In columns 3–6 we divide the sample into four subgroups by residence and hukou status. The regression results show that parents living in urban areas are sensitive to children’s academic performance, either with a city hukou or a rural one. Furthermore, children’s ranking in class most affects the life satisfaction of parents who live in an urban area with a rural hukou. In contrast, the life satisfaction of rural parents seems to be barely affected by their children’s educational performance. Our findings suggest that whether parents live in rural or urban areas matters in terms of whether children’s academic performance significantly affects their parents’ life satisfaction.

In China, given the aforementioned transformation from a planned education system to a market-oriented one, differences in educational resources, including teaching quality, have become increasingly pronounced across provinces, cities and schools (Dello-Iacovo 2009; Mok et al. 2009). High-quality schools are usually located in developed and urban areas, and a child’s chances of getting into a good school depend heavily on the family’s residential location (Xu and Xie 2015). Rural children are more likely to receive a low-quality education because educational resources are unequally distributed across rural and urban areas (Buchmann and Hannum 2001; Hannum and Adams 2009; Knight and Shi 1996). This gives urban children an advantage in the competition with their rural peers. Urban children tend to perform better, bringing more returns on their parents’ investment in their education, and giving stronger motives for urban parents to invest in and devote more to their children’s education. This has in turn led to a stronger impact on urban parents’ life satisfaction. In contrast, rural parents, who are more likely to be less rewarded from this investment, will pay less attention to their children’s education.

In particular, parents living in urban areas with a rural hukou (temporary rural migrant parents) tend to have higher expectations and requirements from their children’s education, for a variety of reasons: these parents are subject to the pressure of social mobility due to their hukou status, are more eager to improve their financial conditions since they tend to rank the lowest in the socioeconomic hierarchy in cities (Wang et al. 2017), and have a strong desire to gain social recognition from their peer groups. These parents tend to alter their perception of education when they move to the cities (Knight and Gunatilaka 2010).

4.2.3 Family Size

Third, we explore family size heterogeneity in the effect of children’s academic performance on parents’ life satisfaction. Specifically, we examine whether the impact of children’s academic performance on parents’ life satisfaction is different across families with different numbers of children. This remains an interesting question given that there is “resource dilution” when it comes to educational investment in families with more than one child. We expect a stronger impact of children’s ranking in class on parents’ life satisfaction for families that have fewer children. This is because an inverse relationship between number of children and educational attainment has been documented in the literature (Lu and Treiman 2008). In other words, children in bigger families tend to have fewer resources available.Footnote 9

We test these hypotheses and show the results in Table 3, Panel C. In columns 1 and 2, we partition the sample into two groups by the number of children in the families: families with a single child, and those with more than one child.Footnote 10 The results suggest a significant effect of children’s academic performance on parents’ life satisfaction for families with a single child (column 1). A one-unit improvement in children’s academic performance is associated with an increase of 5.37 percentage points in the life satisfaction scores of parents. However, for the families with more than one child (column 2), the coefficient of Ranking is not significantly different from zero. This implies that parents with fewer children tend to pay more attention to their children’s education and the “resource dilution” in educational investment exists in China.

4.2.4 Confucianism

Finally, we look at the role of Confucian norm in the relationship between parents’ life satisfaction and children’s academic performance. We follow the study by Chen et al. (2017) to use the number of successful candidates (jinshi holders) in the imperial examination at provincial level as a proxy for Confucianism. The imperial examination can be dated back to a thousand years ago and is one of the key features of Confucianist culture. Jinshi is the highest (national level) degree that one could achieve in the Chinese imperial examination, who could then become appointed as a mid-to-high ranking official. The rewards of holding this degree include economic rewards as holders become a learned class, and ritualistic recognitions by the social public. For such reasons, one has strong incentives to attend the imperial examination to achieve higher social class. These rewards to jinshi degree holders for hundreds of years have fostered a Chinese culture which values education. Thus, we believe the number of jinshi holders in a province can be used to proxy the influence of Confucianism culture. We collect data from databases on Chinese biography books that documented demographic information of 42,949 jinshi holders since the Qing and Ming dynasties, which accounts for 85% of total jinshi holders of all dynasties. We map jinshi holders’ provinces to our data. Given the differences in the population of provinces, we divide the number of jinshi holders by the total population of one province in 2000 to create a jinshi density variable to proxy for the influence of Confucianism in that province.

Following Chen et al. (2017) we classify the provinces in our sample into two categories: one group being provinces that are highly influenced by Confucianism, i.e. with a large number of jinshi to total population in the imperial examination compared to other provinces; and the other group of provinces are ones that are less influenced by Confucianism, which have smaller numbers of jinshi to total population in the imperial examination. Results are shown in columns 1 and 2, Panel D of Table 3, and suggest that the impact of children’s academic performance on parents’ life satisfaction is significant and positive in provinces that are highly influenced by Confucianism (with 1 unit increase in children’s academic performance, parents’ life satisfaction increases by 5.3 percentage points) and not statistically significant in provinces that are less influenced by Confucianism. This confirms our hypothesis that Confucianism can be an important reason why Chinese parents are extremely concerned about their children’s education.

4.3 The Role of Parents’ Involvement in Education

Having shown that children’s academic performance can have an influence on parents’ life satisfaction, we further examine the role of parents’ educational involvement and how this can moderate their life satisfaction. Parents’ educational involvement is reflected by whether they have sent their children to extra-class tutoring and how much they have spent.

For each student and each year, we create a dummy, Training, equal to 1 if child attended private tutoring last month. The interaction term of dummy Training and Ranking is of central interest here and the coefficient for it (shown in column 1 of Table 4) is negative and significant, suggesting that parents’ educational involvement reflected in extra-class tutoring has an adverse impact on their life satisfaction. We then replicate the previous regression using the amount of tuition fees (Ln_fee) to interact with Ranking and the point estimate remains negative and significant (shown in column 2 of Table 4). This indicates that parents’ educational involvement and investment are costly and worsen their life satisfaction to some extent.

5 Robustness Checks

In this section, we perform four robustness checks. First, we investigate a possible endogeneity problem of children’s academic performance. Although panel data analysis partly resolves the issue associated with endogeneity as a result of unobserved heterogeneity, bilateral causality, i.e. simultaneity, still causes endogeneity (Greyling and Rossouw 2017). Hence, we use instrumental variables to replace endogenous variables to solve simultaneity. This study examines whether children’s academic performance has an impact on parents’ life satisfaction. However, the causality could be bilateral. In other words, it is likely that parents’ life satisfaction can also affect children’s academic performance. For instance, according to Berger and Spiess (2011), happier parents are more likely to have a closer relationship with their children, to spend more time in reading/playing with them, etc. This might have a positive effect on the development of the child in general, leading to possible better academic performance.

To deal with this concern, we employ an instrumental variable approach to re-estimate the baseline regression. We replace children’s academic performance with their satisfaction with their class teachers, Chinese language teachers, and math teachers. According to Wang and Holcombe (2010), children’s satisfaction with schoolteachers is positively correlated with their academic performance, given that a better relationship between them creates a friendlier learning environment, hence facilitating children’s academic learning.

The results of the two-stage least squares (2SLS) regressions are shown in Table 5. In columns 1 and 2, we show the results when using the satisfaction of children with their class teachers as the instrumental variable (IV1). First-stage regression results show that satisfaction of children with their class teachers is significantly and positively correlated with their class ranking. A one-unit increase in satisfaction results in a 10-percentage point increase in the class ranking. We rule out the possibility of a weak instrumental variable, as the F-value is 77.980, and according to the rule of thumb a value over 10 is acceptable. The second-stage results show that the estimate of the class ranking is significantly positive, which is consistent with our baseline regression results. Columns 3 and 4 present results when using the three instrumental variables simultaneously (IV2) and we find that they perform well as instrumental variables. Thus, the second-stage results suggest that children’s academic performance significantly improves their parents’ life satisfaction.Footnote 11

Second, we examine whether our findings are robust to different measures of academic performance or life satisfaction. In columns 1 and 2 of Table 6, we report results obtained using an alternative dependent variable, happiness, while the control variables remain the same. In both specifications, the coefficient for class ranking is positive and significant. A one-unit change in the child’s ranking causes a 7.43 or 7.98 percentage point increase in parents’ happiness, which is consistent with our prior results using life satisfaction.

Third, we use two alternative measures for academic performance, which are parents’ evaluation of the child’s performance in language and parents’ evaluation of the child’s performance in math (Language evaluation, Math evaluation, both on a scale of 1–4 with 1 being poor and 4 being excellent). Compared with children’s ranking in class, which is an objective measure, these two alternative measurements are subjective. As shown in columns 3 and 4 of Table 6, the relationship between children’s academic performance and parents’ life satisfaction remains positive. The coefficient is positive and significant for those parents whose evaluation of their children’s academic performance ranks as better.

Finally, our results are robust when we employ an ordered Probit model.Footnote 12 Columns 1–3 of Table 7 show the results using different measures of academic performance, and in column 4 that for life satisfaction. In all specifications, children’s academic performance is positively correlated with parents’ life satisfaction and significant.

6 Discussion

6.1 Main Findings

This study examines the relationship between children’s academic performance and their parents’ life satisfaction, by using a fixed effects model based on a panel data extracted from a national longitudinal survey, the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS).

Our results show that children’s academic performance has a positive and significant effect on parents’ life satisfaction; more specifically, a one-unit increase in the child’s class ranking increases parents’ life satisfaction score by 3.4 percentage points. Among three categories of families according to income levels (low, middle, or high), only the life satisfaction of parents in middle-income families are significantly affected by their children’s academic performance. This offers a novel insight into the phenomenon of middle-class anxiety in China. This is also consistent with the findings of Lareau (2003) in the United States and Kim and Bang (2017) in Korea. Lareau (2003) pointed out that middle-class parents appear to follow a cultural logic of child rearing of “concerted cultivation”, whereby parents strive to develop particular skills and abilities in their children through adult-organized activities. Kim and Bang (2017) found that highly educated middle-class parents place greater emphasis on their children’s studying and are more involved in finding extra educational programs. Furthermore, parents in provinces that are highly influenced by Confucianism pay more attention to their children’s academic performance. Finally, parents living in urban areas and having fewer children are more concerned about their children’s performance than those who live in rural areas and have more children. We found that parents’ educational involvement plays an important role in this relationship and has an adverse effect on their life satisfaction.

Our findings remain robust when using alternative measures for children’s academic performance as well as for parents’ life satisfaction. We also test several other regression models, and the results are consistent with those using the baseline model. To address the potential endogeneity problem of children’s academic performance to parents’ life satisfaction, we employ children’s satisfaction with schoolteachers as an instrumental variable of children’s academic performance and our results remain consistent.

6.2 Limitations and Future Research

There are three limitations in this study that could be addressed in future research. First, our study focused on an empirical analysis of the impact of children’s academic performance on parents’ life satisfaction in China, in light of the profound influence of Confucianism. This impact, however, may not apply to other cultures. There are substantial differences among Asian and Western parents in terms of their expectations on children’s academic performance. According to the study by Chang and Greenberger (2012), parental satisfaction of Chinese American parents is related to their children’s academic performance, nevertheless, this relation was not found among European American parents. Therefore, the implications of our study, notwithstanding that they may apply to other Asian countries including South Korea, Japan, Singapore etc., may not be valid in Western cultures. We leave this to future research to extend our analysis to other cultures.

Our second limitation to the analysis of parents’ life satisfaction is that we did not look at their education expectations. According to Goldenberg et al. (2001), parents adjust their education expectations based on judgments about their children’s future achievement as reflected in educational performance. This, to some extent, could affect children’s academic performance (Coleman 1988; Duran and Weffer 1992). Our regression analysis did not capture the impact of parents’ perceptions and we used fixed effects model to control for potential bias caused by this omitted variable. With data on parents’ perceptions available, one could look at its role in this context by interacting it with children’s academic performance.

Finally, not only the level of children’s academic performance, but also the change of it could affect parents’ life satisfaction. Since CFPS survey was held every other year, it is difficult to collect data regarding the change of children’s academic performance based on three rounds of surveys. According to Grupe and Nitschke (2013), fluctuations in academic performance would increase uncertainty of children’s success in the national test, hence it diminishes parents’ preparation for the future and thus contributes to their anxiety, thereby decreasing their life satisfaction. It would be interesting to look at how fluctuations in children’s academic performance could influence parents’ life satisfaction.

6.3 Policy Implications

Our results have important policy implications. First, the large amount of resources many parents in China devote to their children’s education can be a huge financial burden on the household budget, especially for middle-income families, such that it crowds out other household spending. There is peer competition in educational investment between parents, and parents may feel forced to compete for better rankings of their children. Instead, education should focus on the development of children’s intellectual abilities as well as their healthy personalities. Another concern for policy makers is that the high cost of education may lower the birth rate, which would be potentially harmful given the problem of the aging population in China. Though the one-child policy has been abolished, the number of children families have has not increased as expected, and the extremely high education cost may be one of the reasons for this. Therefore, it is of great importance for the government to emphasize the purpose of education and to direct parents to more rational educational investment. Furthermore, policy makers and regulators should be aware of the growing demand for “shadow education,” and that sector needs regulation as a supplement to formal schooling.

Our findings also show that parents from different income groups differ when it comes to the question of whether their children’s academic performance can affect their life satisfaction. It is of concern that parents in low-income families tend to show less interest in their children’s academic achievements, such that a lower educational investment in their children may lead to poorer academic performance, which in turn lowers the educational aspirations of low-income families. This creates a vicious circle and undermines social mobility. It is hence important for policy makers to provide more educational resources for lower-income families, and to encourage them to pay more attention to their children’s education.

Notes

In China, 93% of parents pay for private tuition, and the average spending on children’s education from primary through to undergraduate education has been reported to be US$42,892. In this regard, Hong Kong parents ranked first, spending on average US$132,161 on one child’s education. Singapore, Taiwan and Mainland China ranked third, fifth and sixth respectively among the 15 countries and regions surveyed (which included North American and European countries, among others) (HSBC 2017). According to statistics published by the Chinese Society of Education, there are around 200,000 extra-class tutoring institutions across China, and the market for primary and middle school tutoring alone was to be some RMB800 billion in 2016. There were 137,000,000 students participating in extra-class education and around 8 million teachers involved (Chinese Society of Education 2016).

Many Chinese parents move home to be within the catchment area (in China, termed the “neighborhood school policy”) of a high-quality school, and houses within such catchment areas are usually exceptionally expensive for that very reason.

The closest study to ours is that of Chang and Greenberger (2012), which investigates ethnic differences in the parenting satisfaction of mothers who have college-enrolled children, using cross-sectional survey data from 140 mothers living in the U.S. Our study, aside from looking at a different cultural and ethnic group, differs from theirs by looking at students in primary, middle and high school, as opposed to college students.

The elimination of the employment substitution (dingti) system for workers in the public sector in China has also led to changes in employment. Dingti refers to an option available to an adult–child to take a parent's job after that parent leaves work as a result of sudden death, prolonged illness, or retirement (Davis 1988). First appearing in state enterprises in 1953 as a form of welfare for families in financial hardship, this system was extended to all state employees in 1978, but was abolished in 1986, when the system of contract labor became the officially sanctioned recruitment method. However, owing to loose enforcement of the new system, dingti continued until the mid-1990s, by which time it had lasted more than 40 years. According to Davis (1988), in the eight enterprises she visited in 1979, on average 80% of retirees used the dingti option in the first half of 1979, and nearly all new employees were children of retirees.

We convert the 1–5 scale to a 0-–10 scale by subtracting 1 and multiplying by 2.5, consistent with Liebman and Mahoney (2017).

First, we obtain the average ranking in class by taking the average of the specific numbers of the two ranks and then dividing them by class size. Second, we classify average ranking in class into five categories: 1 (top 10%), 2 (top 11–25%), 3 (top 26–50%), 4 (top 51–75%), and 5 (bottom 24%).

Ferrer-i-Carbonell and Frijters (2004) pointed out that as long as the model is set up correctly, it does not matter whether subjective well-being is seen as a sequential variable estimated using ordered probit or seen as a continuous variable estimated using OLS. We use the OLS individual fixed-effect model with robust standard errors, since it is easier to interpret the coefficient. Nevertheless, similar conclusions are obtained from ordered probit specifications for the results in the robustness tests, reported below.

In our sample, for the low-income families, annual household per capita income was less than RMB3833 in 2010, less than RMB5000 in 2012 and less than RMB5892 in 2014. For middle-income families, annual household per capita income was RMB3833–9025 in 2010, RMB5000–11,975 in 2012, and RMB5892–13,333 in 2014. For high-income families, annual household per capita income was more than RMB9025 in 2010, more than RMB11,975 in 2012, and more than RMB13,333 in 2014.

Partly due to the “one child policy” established in 1979, Chinese families have become smaller in size and hence, according to our hypothesis, parents’ expectations of each child are greater (Dello-Iacovo 2009).

We also divided the sample according to whether the families had 2 children or more than 2 children, and the findings are robust. The results are available upon request.

One major concern of the endogeneity problem in our case is that we may overvalue the impact of children’s academic performance, since it is endogenous to parents’ life satisfaction. However, the point estimates from employing instrumental variables are greater (0.3693 and 0.2510) than that (0.0340) of the baseline regression, which implies that the impact from the baseline regression has not been overvalued or undervalued. The substantial increase in the point estimate using IV may contribute to local average treatment effects.

Because of the ordinal nature of the dependent variable, “life satisfaction” or “happiness,” an ordered probit method is used to estimate a happiness equation as the robustness check.

References

Andreoni, J., & Sprenger, C. (2012). Risk preferences are not time preferences. American Economic Review, 102(7), 3357–3376.

Angeles, L. (2010). Children and life satisfaction. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11(4), 523–538.

Berger, E. M., & Spiess, C. K. (2011). Maternal life satisfaction and child outcomes: Are they related? Journal of Economic Psychology, 32(1), 142–158.

Bodycott, P. (2009). Choosing a higher education study abroad destination: What mainland Chinese parents and students rate as important. Journal of Research in International Education, 8(3), 349–373.

Bosker, M., Brakman, S., Garretsen, H., & Schramm, M. (2012). Relaxing hukou: Increased labor mobility and China’s economic geography. Journal of Urban Economics, 72(2–3), 252–266.

Buchmann, C., & Hannum, E. (2001). Education and stratification in developing countries: A review of theories and research. Annual Review of Sociology, 27, 77–102.

Cao, Y., Qian, Y., & Weingast, B. R. (1999). From federalism, Chinese style to privatization, Chinese style. Economics of Transition, 7(1), 103–131.

Chan, K. W. (2010). The household registration system and migrant labor in China: Notes on a debate. Population and Development Review, 36(2), 357–364.

Chang, E. S., & Greenberger, E. (2012). Parenting satisfaction at midlife among European- and Chinese-American mothers with a college-enrolled child. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 3(4), 263–274.

Charbonneau, É., & Van Ryzin, G. G. (2012). Performance measures and parental satisfaction with New York City schools. American Review of Public Administration, 42(1), 54–65.

Chen, T., Kung, J. K.-S., & Ma, C. (2017). Long live Keju! The persistent effects of China’s imperial examination system. Working paper.

Cheng, T., & Selden, M. (1994). The origins and social consequences of China’s hukou system. China Quarterly, 139, 644–668.

Chinese Society of Education. (2016). Survey report on current situation of teachers in Chinese tutoring education and tutoring institutions. Beijing: The Chinese Society of Education.

Clark, A. E., Frijters, P., & Shields, M. A. (2008). Relative income, happiness, and utility: An explanation for the Easterlin paradox and other puzzles. Journal of Economic Literature, 46(1), 95–144.

Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, S95–S120.

Connelly, R., & Zheng, Z. (2003). Determinants of school enrollment and completion of 10 to 18 year olds in China. Economics of Education Review, 22(4), 379–388.

Cook, S. (2002). From rice bowl to safety net: Insecurity and social protection during China’s transition. Development Policy Review, 20(5), 615–635.

Davis, D. (1988). Unequal chances, unequal outcomes: Pension reform and urban inequality. China Quarterly, 114, 223–242.

Dello-Iacovo, B. (2009). Curriculum reform and ‘Quality Education’ in China: An overview. International Journal of Educational Development, 29(3), 241–249.

Diener, E. (2000). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist, 55(1), 34–43.

Diener, E., Gohm, C. L., Suh, E., & Oishi, S. (2000). Similarity of the relations between marital status and subjective well-being across cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 31(4), 419–436.

Ding, W., Lehrer, S. F., Rosenquist, J. N., & Audrain-McGovern, J. (2009a). The impact of poor health on academic performance: New evidence using genetic markers. Journal of Health Economics, 28(3), 578–597.

Ding, X., Yue, C., & Sun, Y. (2009b). The influence of China’s entry into the WTO on its education system. European Journal of Education, 44(1), 9–19.

Duran, B. J., & Weffer, R. E. (1992). Immigrants’ aspirations, high school process, and academic outcomes. American Educational Research Journal, 29(1), 163–181.

Easterlin, R. A. (2001). Income and happiness: Towards a unified theory. Economic Journal, 111(473), 465–484.

Easterlin, R. A., McVey, L. A., Switek, M., Sawangfa, O., & Zweig, J. S. (2010). The happiness–income paradox revisited. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(52), 22463–22468.

Feng, H., & Lu, M. (2013). School quality and housing prices: Empirical evidence from a natural experiment in Shanghai, China. Journal of Housing Economics, 22(4), 291–307.

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A., & Frijters, P. (2004). How important is methodology for the estimates of the determinants of happiness? The Economic Journal, 114(497), 641–659.

Gelber, A., & Isen, A. (2013). Children’s schooling and parents’ behavior: Evidence from the Head Start Impact Study. Journal of Public Economics, 101(1), 25–38.

Gibbons, S., & Silva, O. (2011). School quality, child wellbeing and parents’ satisfaction. Economics of Education Review, 30(2), 312–331.

Goldenberg, C., Gallimore, R., Reese, L., & Garnier, H. (2001). Cause or effect? A longitudinal study of immigrant Latino parents’ aspirations and expectations, and their children’s school performance. American Educational Research Journal, 38(3), 547–582.

Greyling, T., & Rossouw, S. (2017). Non-economic quality of life and population density in South Africa. Social Indicators Research, 134(3), 1051–1075.

Greyling, T., & Tregenna, F. (2017). Construction and analysis of a composite quality of life index for a region of South Africa. Social Indicators Research, 131(3), 887–930.

Grupe, D. W., & Nitschke, J. B. (2013). Uncertainty and anticipation in anxiety: An integrated neurobiological and psychological perspective. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 14(7), 488–501.

Hannum, E., & Adams, J. (2007). Girls in Gansu, China: Expectations and aspirations for secondary schooling. In M. A. Lewis & M. E. Lockheed (Eds.), Exclusion, gender and schooling: Case studies from the developing world (pp. 71–98). Washington, DC: Center for Global Development.

Hannum, E., & Adams, J. (2009). Beyond cost: Rural perspectives on barriers to education. In D. Davis & F. Wang (Eds.), Creating wealth and poverty in postsocialist China (pp. 156–171). Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Hansen, T. (2012). Parenthood and happiness: A review of folk theories versus empirical evidence. Social Indicators Research, 108(1), 29–64.

HSBC. (2017). The value of education: Higher and higher. Global report. London: HSBC Holdings plc.

Hvistendahl, M. (2009). A poor job market and a steady currency feed “overseas-study fever” in China. Chronicle of Higher Education, 55(25), 29.

Kalil, A. (2015). Inequality begins at home: The role of parenting in the diverging destinies of rich and poor children. In P. R. Amato, A. Booth, S. M. McHale, & J. Van Hook (Eds.), Families in an era of increasing inequality: Diverging destinies (pp. 63–82). Cham: Springer.

Kim, J.-S. (2013). Stratification phenomenon of educational aspirations-with a focus on ‘cooling-down pattern’ of educational aspirations among the working-class. Asia-Pacific Collaborative Education Journal, 9(1), 27–39.

Kim, J.-S., & Bang, H. (2017). Education fever: Korean parents’ aspirations for their children’s schooling and future career. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 25(2), 207–224.

Knight, J., & Gunatilaka, R. (2010). Great expectations? The subjective well-being of rural–urban migrants in China. World Development, 38(1), 113–124.

Knight, J., & Shi, L. (1996). Educational attainment and the rural–urban divide in China. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 58(1), 83–117.

Lam, C.-C., Ho, E. S. C., & Wong, N.-Y. (2002). Parents’ beliefs and practices in education in Confucian heritage cultures: The Hong Kong case. Journal of Southeast Asian Education, 3(1), 99–114.

Lareau, A. (2003). Unequal childhoods: Class, race, and family life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Larsen, J., Axhausen, K. W., & Urry, J. (2006). Geographies of social networks: Meetings, travel and communications. Mobilities, 1(2), 261–283.

Lei, X., Shen, Y., Smith, J. P., & Zhou, G. (2015). Do social networks improve Chinese adults’ subjective well-being? The Journal of the Economics of Ageing, 6, 57–67.

Leung, J. T. Y., & Shek, D. T. L. (2011). Expecting my child to become “dragon” - development of the Chinese parental expectation on child's future scale. International Journal on Disability and Human Development, 10(3), 257–265.

Li, H., Li, L., Wu, B., & Xiong, Y. (2012). The end of cheap Chinese labor. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 26(4), 57–74.

Liebman, J. B., & Mahoney, N. (2017). Do expiring budgets lead to wasteful year-end spending? Evidence from federal procurement. American Economic Review, 107(11), 3510–3549.

Lin, J., & Zhang, Y. (2006). Educational expansion and shortages in secondary schools in China: The bottle neck syndrome. Journal of Contemporary China, 15(47), 255–274.

Lu, Y., & Treiman, D. J. (2008). The effect of sibship size on educational attainment in China: Period variations. American Sociological Review, 73(5), 813–834.

Lucas-Thompson, R. G., Goldberg, W. A., & Prause, J. (2010). Maternal work early in the lives of children and its distal associations with achievement and behavior problems: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 136(6), 915–942.

MacLeod, J. (2018). Ain’t no makin’it: Aspirations and attainment in a low-income neighborhood. New York: Routledge.

Margolis, R., & Myrskyla, M. (2016). Children’s sex and the happiness of parents. European Journal of Population, 32(3), 403–420.

Mayer, S. E. (1997). What money can’t buy: Family income and children’s life chances. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Mok, K. H., Wong, Y. C., & Zhang, X. (2009). When marketisation and privatisation clash with socialist ideals: Educational inequality in urban China. International Journal of Educational Development, 29(5), 505–512.

Mullainathan, S., & Shafir, E. (2013). Decision making and policy in contexts of poverty. In E. Shafir (Ed.), Behavioral foundations of public policy (pp. 281–300). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Nelson, S. K., Kushlev, K., English, T., Dunn, E. W., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2013). In defense of parenthood: Children are associated with more joy than misery. Psychological Science, 24(1), 3–10.

Nomaguchi, K. M. (2012). Parenthood and psychological well-being: Clarifying the role of child age and parent–child relationship quality. Social Science Research, 41(2), 489–498.

Ogbu, J. U. (1987). Variability in minority school performance: A problem in search of an explanation. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 18(4), 312–334.

Oketch, M., Mutisya, M., & Sagwe, J. (2012). Parental aspirations for their children’s educational attainment and the realisation of universal primary education (UPE) in Kenya: Evidence from slum and non-slum residences. International Journal of Educational Development, 32(6), 764–772.

Ott, J. C. (2010). Good governance and happiness in nations: Technical quality precedes democracy and quality beats size. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11(3), 353–368.

Phalet, K., & Schönpflug, U. (2001). Intergenerational transmission of collectivism and achievement values in two acculturation contexts: The case of Turkish families in Germany and Turkish and Moroccan families in the Netherlands. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32(2), 186–201.

Portes, A., & Rumbaut, R. G. (2001). Legacies: The story of the immigrant second generation. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Posel, D. R., & Casale, D. M. (2011). Relative standing and subjective well-being in South Africa: The role of perceptions, expectations and income mobility. Social Indicators Research, 104(2), 195–223.

Pushkar, D., Bye, D., Michael, C., Wrosch, C., Chaikelson, J., Etezadi, J., et al. (2014). Does child gender predict older parents’ well-being? Social Indicators Research, 118(1), 285–303.

Ram, R. (2009). Government spending and happiness of the population: Additional evidence from large cross-country samples. Public Choice, 138(3–4), 483–490.

Reyes-García, V., Angelsen, A., Shively, G. E., & Minkin, D. (2019). Does income inequality influence subjective wellbeing? Evidence from 21 developing countries. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20(4), 1197–1215.

Seirawan, H., Faust, S., & Mulligan, R. (2012). The impact of oral health on the academic performance of disadvantaged children. American Journal of Public Health, 102(9), 1729–1734.

Sharma, Y. (2013). Asia’s parents suffering “education fever.” BBC News, October 22, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2018, from https://www.bbc.com/news/business-24537487.

Song, Y. (2014). What should economists know about the current Chinese hukou system? China Economic Review, 29, 200–212.

Wang, X., Bai, Y., Zhang, L., & Rozelle, S. (2017). Migration, schooling choice, and student outcomes in China. Population and Development Review, 43(4), 625–643.

Wang, M.-T., & Holcombe, R. (2010). Adolescents’ perceptions of school environment, engagement, and academic achievement in middle school. American Educational Research Journal, 47(3), 633–662.

Wu, Y. (2013). The keypoint school system, tracking, and educational stratification in China, 1978–2008. Sociological Studies, 4, 179–202. (in Chinese).

Wu, X. (2017). Higher education, elite formation and social stratification in contemporary China: Preliminary findings from the Beijing College Students Panel Survey. Chinese Journal of Sociology, 3(1), 3–31.

Wu, Y., & Zhu, J. (2016). When are people unhappy? Corruption experience, environment, and life satisfaction in Mainland China. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(3), 1125–1147.

Xu, H., & Xie, Y. (2015). The causal effects of rural-to-urban migration on children’s well-being in China. European Sociological Review, 31(4), 502–519.

Yuan, H. (2016). Structural social capital, household income and life satisfaction: The evidence from Beijing, Shanghai and Guangdong-Province, China. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(2), 569–586.

Zheng, R. (2017). How children’s education became the new luxury status symbol for Chinese parents. Jing Daily, October 10, 2017. Retrieved July 10, 2018, from https://jingdaily.com/how-childrens-education-became-a-luxury-status-symbol/.

Zhou, Y., & Wang, D. (2015). The family socioeconomic effect on extra lessons in Greater China: A comparison between Shanghai, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macao. Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 24(2), 363–377.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the Institute of Social Science Survey at Peking University for providing us with the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) data. This paper has greatly benefitted from comments of Kezhong Zhang, Yuanyuan Ma and Xin Wan, and comments from seminar participants at Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Zhongnan University of Economics and Law, and comments from participants at 28th Annuals Conference of Chinese Economics Association in the UK. This paper was partly written while I was visiting University of Nottingham and I am very grateful to Lina Song, Jing Zhang, Kun Bao, Zhiyi Ren and professors in Chinese Studies Centre for their help and their hospitality.

Funding

This study was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 71403296), National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 15BJL088) and Humanities and Social Sciences Foundation of the Ministry of Education of China (Grant No. 19YJC790090).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Y., Huang, R., Lu, Y. et al. Education Fever in China: Children’s Academic Performance and Parents’ Life Satisfaction. J Happiness Stud 22, 927–954 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00258-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00258-0