Abstract

While developing excellence in knowledge and skills, academic institutions have often overlooked their obligation to instill wellbeing. To address this, we introduced a 14-week positive psychology intervention (PPI) program (Happiness 101) to university students from 39 different nations studying in the United Arab Emirates (N = 159). Students were exposed to 18 different PPIs. Pre, post, and 3-month-post measures were taken assessing hedonic and eudaimonic well-being, and beliefs regarding the fear and fragility of happiness. At the end of the semester, relative to a control group (N = 108), participants exposed to the Happiness 101 program reported higher levels of both hedonic and eudaimonic well-being, and lower levels of fear of happiness and the belief that happiness is fragile. Boosts in life satisfaction and net-positive affect, and reduction of fear of happiness and the belief that happiness is fragile were maintained in the Happiness 101 group 3 months post-intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Organizations such as business and governments are now taking a serious interest in their constituents’ wellbeing and are identifying ways in which wellbeing can be improved. Concern for constituents’ wellbeing is also important within academia. Focusing on the delivery of academics along with the application of skills to promote wellbeing, positive education (Green et al. 2011)—an extension of positive psychology—views schools and universities as ideal developmental settings in which to teach the social, moral, emotional, and intellectual skills required to enhance and sustain individual wellbeing (Norrish et al. 2013; Oades et al. 2011; Seligman et al. 2009; Waters 2011; White and Waters 2015). Empirically validated interventions and programs that target student wellbeing have become part of this focus. Yet, the subject of wellbeing in education remains marginal, as it is often considered to deviate from academic learning (Shoshani and Steinmetz 2014; White 2016). However, youth need guidance beyond academics in order to become fully flourishing adults who contribute to society and the workplace in meaningful ways, while flourishing in their personal lives (Kern et al. 2015; Wong, 2011). Thus, the challenge for universities is to find ways to fulfill their role and responsibility in cultivating wellbeing by teaching young adults the skills they need to flourish (Oades et al., 2011; Waters, 2011; White and Waters, 2015).

2 Why Focus on Wellbeing?

Greater wellbeing offers a myriad of benefits to individuals and the societies in which they live. In a review of 225 studies, Lyubomirsky et al. (2005a, b) showed that while access to tangible resources can lead to greater happiness, the weight of evidence suggests the reverse to be true. That is, that greater initial wellbeing results in greater subsequent benefits across multiple domains, in the areas of employment, relationships, health, and even personal finances. Indeed, the benefits of greater wellbeing across many life domains are well established. For example, individuals with higher wellbeing had superior financial earnings (Judge et al. 2010), exhibited more compassion and cooperation (Lount 2010; Nelson 2009), and volunteered more often as well as donated more time and money (Aknin et al. 2013; Priller and Shupp 2011) compared to those with lower levels of wellbeing. Individuals with high wellbeing are also more likely to use seatbelts (Goudie et al. 2012), engage in physical activity (Huang and Humphreys 2012), eat nutritious diets (Boehm and Kubzansky 2012) and be non-smokers (Grant et al. 2009). Less racial bias and more pro-social behaviour are found among those with high wellbeing (Johnson and Fredrickson 2005). Experiencing positive emotions, a proxy for wellbeing, has been demonstrated to enhance attention, generate more frequent and flexible ideas, and boost one’s creative problem solving skills (Kok et al. 2008). In the workplace, employees with greater wellbeing are more productive, satisfied, and committed to their careers (Erdogan et al. 2012); moreover, optimism (another proxy for wellbeing) predicts workplace success and confidence in career-related decisions (Creed et al. 2002; Neault 2002).

3 Positive Psychological Interventions

Wellbeing is, to some extent, malleable (Lyubomirsky et al. 2005a, b), particularly via engaging in activities specifically geared towards that end. Within the domain of positive psychology, such actions are deemed Positive Psychology Interventions (PPIs); PPIs are empirically validated, purposeful activities designed specifically to increase the frequency of positive emotions and experiences, and which help to facilitate the use of actions and thoughts that lead to flourishing (Sin and Lyubomirsky 2009). PPIs have been successfully used by organizations (Mills et al. 2013) and in healthcare (Kahler et al. 2014; Lambert D’raven et al. 2015) and clinical settings (Huffman et al. 2014; Seligman et al. 2005, 2006). PPIs are cost effective and easy to deliver, while being non-stigmatizing and lacking side effects (Layous et al. 2011). Several meta-analyses (Bolier et al. 2013; Hone et al. 2015; Sin and Lyubomirsky 2009; Weiss et al. 2016) have evidenced that PPIs reliably increase wellbeing and reduce depressive symptoms over time.

Recent reviews have illustrated the broad range of validated PPIs (see Lambert D’raven and Pasha-Zaidi 2014a; Rashid 2015). For instance, individuals can reinforce their relationships via capitalization, the act of responding positively to other’s good news and supporting their efforts (Gable and Reis 2010). Kind acts distract individuals from problems, raise self-efficacy, and increase happiness (Dillard et al. 2008; Dunn et al. 2008), while writing about positive events increases wellbeing and decreases depression (Burton and King 2009; Shapira and Mongrain 2010), much like writing about or showing gratitude (Boehm et al. 2011; Lyubomirsky et al. 2011). Finding positive benefits in the experience of negative events also results in less depression, as shown in Helgeson et al. (2006) meta-analysis. Other PPIs have demonstrated efficacy in shielding individuals against stress and negative emotions; these include becoming selective about whom, and in what activity, one invests emotional time and energy (Aaker et al. 2011; Dunn et al. 2011), and developing purpose by asserting one’s values, (Creswell et al. 2005; Diener et al. 2012).

Although PPIs have been successfully implemented in some educational institutions (Brunwasser et al. 2009; Seligman et al. 2009; Shoshani and Steinmetz 2014), the need for positive education has more commonly been identified at the primary and secondary levels. For example, a review by Waters (2011) highlighting primary and secondary school-based programs illustrates the breadth of, and possibilities for, the use of PPIs in educational settings. Such programs have focused on the development of gratitude (Froh et al. 2009; Froh et al. 2008), mindfulness (Broderick and Metz 2009; Huppert and Johnson 2010), character strengths (Park and Peterson 2008), and resiliency (Seligman et al. 2009), with each program/PPI improving anxiety, depression, somatic complaints, optimism, relationships, hopelessness, the ability to deal with stress and trauma, in addition to improving school performance. A meta-analysis of 213 programs from kindergarten through high school substantiated Water’s review, providing further evidence that positive interventions lead to stronger achievement test results (Durlak et al. 2011). Such evidence negates the concern that focusing on wellbeing detracts attention from academic learning (Bernard and Walton 2011; Suldo et al. 2011).

Nonetheless, despite this evidence of the benefits of positive education, higher education is frequently left out of discussions involving the implementation of wellbeing skills (Norrish et al. 2013; Oades et al. 2011). As such, few PPI programs exist in post-secondary institutions. In the current study we aimed to address this gap; we offer evidence of a PPI program delivered to a group of international university students in the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

4 Divergent Views on Happiness

Although wellbeing yields many benefits, recent research is challenging long-standing assumptions about the universal desirability of happiness. Culture and religion significantly affect how happiness is understood, pursued, and desired (Diener et al. 2013; Lambert D’raven and Pasha-Zaidi 2014b), with studies revealing negative perceptions of happiness. Indeed, fear of happiness and a belief in its fragility exist across a range of cultures (Joshanloo 2013a; Joshanloo and Weijers 2013). For example, Joshanloo and Weijers (2013) found that in the West, depressed patients often express the fear of becoming happy and losing control over their emotions. This fear is also prevalent in Asian cultures where happiness is believed to threaten relationships, invite jealousy, upset social harmony, or bring disaster. In Islamic cultures, the expression of happiness is further believed to tempt fate and call forth the evil eye, and is thought to make individuals appear less serious, mature, and responsible, as well as facilitating a path to sin. In Iran, sadness is viewed favorably and is often associated with insight and personal depth (Joshanloo 2013a), causing individuals to shun the expression of happiness.

As such, fear of happiness revolves around the belief that positive emotions, such as joy, excitement, or cheerfulness, can bring forward negative consequences (Joshanloo et al. 2014). Fragility of happiness involves the belief that happiness is controlled by a higher power, is subject to its will, and can be extinguished if pursued too vehemently and, thus, is fragile and fleeting (Joshanloo et al. 2015). Research shows that fear and fragility beliefs are prevalent across many cultures, but more so in non-Western cultures, including the Islamic ones (Joshanloo et al. 2014, 2015). Thus, despite the benefits of happiness on wealth, health, and relationships, the belief that happiness is desirable is not universally shared.

Religious beliefs embedded within cultural beliefs also appear to directly influence happiness and wellbeing. Indeed, studies consistently evidence that religion is a source of wellbeing in itself (Abu-Raiya et al. 2016; Kashdan and Nezlek 2012; Tay et al. 2014), in particular with respect to Muslims (Gulamhussein and Eaton 2015; Parveen et al. 2014; Sahraian et al. 2013; Thomas et al. 2016). Moreover, religious people in religious nations have higher levels of happiness than do religious people in nonreligious nations (Diener et al. 2011). Consequently, culture and religion indeed matter in questions of wellbeing (see also Magyar-Moe et al. 2015). Advocates have strongly encouraged that the next stage in positive psychology’s development is to consider wellbeing from diverse cultural views (Tajdin 2015; Wong 2013). Scholars have noted the well-established need in the Middle East/North Africa (MENA) region for a culturally-appropriate approach to viewing, and enhancing, wellbeing (Lambert et al. 2015); this region currently lacks academic scholarship in the positive psychology field (Brannan et al. 2013; Joshanloo 2016; Rao et al. 2015). Accordingly, more investigation is required to determine whether the fear and fragility of happiness can be manipulated, whether the use of PPIs in a predominantly non-Western setting can achieve wellbeing gains over time, and whether levels of religiosity are impacted by education about, and use of, PPIs. We sought to help address this research gap.

5 The Present Study

The purpose of this study was, thus, twofold: (1) to evaluate changes in wellbeing after participating in a semester-long happiness program relative to a control group, and (2), to examine the impact of such a program on the fear and fragility of happiness beliefs, as well as religiosity, among a culturally diverse group of university students.

6 Method

6.1 Participants

A total of 268 students participated in the study (Tx group: n = 159; male = 62, female = 97, age range: 17-43, Mage = 21.11, SDage = 3.41; Control group: n = 108, male = 56, female = 52, age range: 18-35, Mage = 21.44, SDage = 2.79). A broad range of nationalities (39 in total) were represented with Nigerian (10.01%), Emirati (7.5%), and Indian (7.1%) composing the largest groups (see Table 1 for detailed counts). Participants were predominantly Muslim (77.61%) followed by Catholic/Christian (12.69%; see Table 1 for detailed counts). All students (with the exception of 13 participants who were Emirati nationals in the intervention group and 7 in the control group) were expatriate students currently living in Dubai (UAE) and enrolled in a 4-year university program. All participants were from the same university; intervention group participants were enrolled in the Introduction to Psychology course while control group participants were not enrolled in the course. The major and year of each student was not solicited as the course was an open elective and students came from a diversity of programs such as engineering, IT, communications, architecture, and health sciences. All students were from second year onwards as the course required a 1 year English prerequisite. The language of teaching is English.

6.2 Procedure

The Ethics Review Board granted approval for the study; all participants gave informed consent and were informed that they could withdraw their results from the study at any time. A total of 10 introductory psychology sections were offered from January 2015 to the end of 2016 in which students participated in the 14-week Happiness 101 program (Lambert 2012, 2016), which was previously developed by the first author and evaluated in a primary healthcare setting (Lambert D’raven et al. 2015). The Happiness 101 program was embedded in the Introduction to Psychology courses taught by the first author and primary investigator, the status of which students were aware. The program was presented to students as a program that had been shown to work in other cultures. While students were aware that their responses were part of a study, emphasis was placed on the information and interventions rather than on the research aspect of the study. Measures were taken at the start and end of the 14-week program and again at 3 months post-treatment. To maintain objectivity, the data were analyzed independently by the second and third authors. Eighteen validated PPIs were undertaken during classes over the course of the semester (e.g., engaging in good deeds, writing a gratitude letter, using mindfulness, savoring; see Table 2 for an overview of the program including the full set of PPIs employed), with recommendations to practice them over the course of the week.

Many intervention studies have been criticized for merely assessing one or a handful of PPIs in isolation, and for not being framed upon a theoretical orientation to contextualize or guide their work (Gander et al. 2016). The Happiness 101 program is structured according to the PERMA (Seligman 2011) model. The PERMA model highlights five pathways (Positive Emotion, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishments) thought to best reflect the ways in which individuals achieve wellbeing. Various PPIs were selected to reflect each pathway, much like the Gander et al. (2016) study, which used PERMA as its theoretical orientation and evaluated the overall effects of selected PPIs according to each pathway. For instance, writing a gratitude letter was included in the pathway of Relationships, savoring in the Positive Emotion pathway, and writing a reverse bucket list in the Accomplishments pathway. In addition, positive psychology concepts such as adaptation (Lyubomirsky 2011), flow (Csikszentmihalyi 1990), the broaden and build model (Fredrickson 2006), and the architecture of sustainable happiness (Lyubomirsky et al. 2005a, b) were introduced. Understanding how positive psychology contrasts with traditional psychology was also discussed as part of psychology’s historical development. Group discussions, along with written or in-class activities, facilitated instruction. Although religious beliefs and beliefs regarding fear and fragility of happiness were of interest in the study, these constructs were not directly addressed in the classes or written materials. Participants received course credit; participants were not involved in any additional university support programmes.

6.3 Measures

Wellbeing is multidimensional and comprises both feeling good and functioning well, hedonia and eudaimonia respectively (Keyes and Annas 2009; Ryan and Deci 2001; cf. Kashdan et al. 2008). Both hedonia and eudaimonia are necessary for complete flourishing and wellbeing (Kern et al. 2015; Keyes 2005; Waterman et al. 2010), thus, both feeling good and functioning well were assessed. We used a variety of measures not only to capture nuanced aspects of well-being, but also to help determine if differences or gains in well-being held true across different well-being measures (as per Passmore et al. 2017). This was of particular interest with respect to eudaimonia, given the diverse conceptual backgrounds informing this construct (e.g., Keyes 2002; Huta and Waterman 2014; Ryan et al. 2008; see also review by Lambert et al. 2015). As noted in the introduction, we felt it equally important to assess the effects that learning about, and using, PPIs would have on beliefs regarding the fear and fragility of happiness as well as impact on level of religiosity. Moreover, given the direct contribution that religiosity has on well-being, we also deemed it important to control for religion in our analyses as it is possible that initial levels of religiosity could affect well-being trajectories of our participants.

A total of eight measures were utilized (described in detail below): two measures of hedonic well-being: (1) Scale of Positive and Negative Experience, (2) Satisfaction with Life Scale; two measures of eudaimonic well-being: (1) Flourishing Scale, (2), Questionnaire of Eudaimonic Well-Being; one measure of overall mental health: The Mental Health Continuum—Short Form; two measures pertaining to happiness beliefs: (1) Fear of Happiness Scale, (2) The Fragility of Happiness Scale; and one measure of religiosity: Brief Version of the Santa Clara Strength of Religious Faith Questionnaire.

Scale of Positive and Negative Experience (SPANE; Diener et al. 2009, 2010). The 12-item SPANE measures positive feelings (SPANE-P), negative feelings (SPANE-N), and the balance between the two (SPANE-B). It is considered appropriate to use in culturally diverse settings as it does not include lists of emotions that might be problematic for non-English speakers, rather it uses terms like “good”, “bad”, “positive” and so forth. The SPANE was shown to have good reliability and validity (Diener et al. 2010), as well as high factor loadings for the SPANE-P and SPANE-N. The construct validity of the overall SPANE was good, with moderate to very high correlations with other emotion and wellbeing measures. Cronbach’s alphas in the current study were between .74, and .81.

Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al. 1985). The 5-item SWLS assesses an individual’s overall judgment of satisfaction with their life as a whole versus specific life domains (Pavot and Diener 2008). Items (e.g., “I am satisfied with my life”, “If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing”) are rated on a 7-point scale with end points of 1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree. Scores range from 5 to 35, with the neutral point at 20. The SWLS has been shown to have high internal consistency (0.79 and higher), while test–retest reliability and convergent validity is also high (Pavot and Diener 1993). The SWLS is a widely used wellbeing measure (Larsen and Eid 2008; Pavot and Diener 2008). Cronbach’s alphas in the current study were .74, .76, .74.

Flourishing Scale (FS; Diener et al. 2009). The FS is an 8-item measure of social psychological prosperity. It includes the following: having a sense of competence, feeling engaged and interested, reporting meaning and purpose, feeling a sense of optimism, accepting the self, having supportive and rewarding relationships, contributing to the wellbeing of others, and being respected by others. Items (e.g., “I am engaged and interested in my daily activities”, “I am optimistic about my future”) are rated on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. The FS has shown high reliability and validity in college student samples (Diener et al. 2010). The construct validity of the FS was acceptable, based on its moderate to high correlations with scores on several other wellbeing measures (rs = .78, 73). Cronbach’s alphas in the current study were .80, .84, .83.

Questionnaire of Eudaimonic Well-Being (QEWB; Waterman et al. 2010). Eudaimonic wellbeing involves the development of potentials and fulfillment of personal goals; thus, it is based on activity and not solely on what individuals think about their life or feel at a given moment. The 21-item QEWB measures effort, self-discovery, enjoyment, purpose and meaning, development of one’s potentials, and involvement. Waterman et al. (2010) found all items to load onto a single factor with high internal consistency suggesting altogether that the psychometric properties of the QEWB can be considered acceptable. Examples of the items include, “I believe I have discovered who I really am” and “When I engage in activities that involve my best potentials, I have this sense of really being alive”. Cronbach’s alphas in the current study were .76, .79, .80.

The Mental Health Continuum Short Form (MHC-SF; Keyes 2009). The MCH-SF measures three sources of wellbeing, i.e., social (social integration and contribution), emotional (positive emotion and satisfaction with life), psychological (autonomy and personal growth). The 14-item scale has been validated across many cultural contexts (Joshanloo et al. 2013; Khumalo et al. 2012) and has good test–retest reliability over 3 months (Lamers et al. 2012). Diagnoses range from flourishing mental health (upper limits), languishing (lower limits), and moderate mental health for those who are neither flourishing nor languishing. Recently, the MCH-SF was tested in student samples from 38 different countries (N = 8066; Zemojtel-Piotrowska et al. 2018). Zemojtel-Piotrowska and colleagues recommended the use of an overall mental health score—that is, treating scores from the MCH-SF as a single dimension—given that differentiation between the subscales was not strongly pronounced, particularly in more collectivistic countries. Thus in the current study, we calculated only an overall score of mental health. Cronbach’s alphas in the current study were .85, .89, .87.

Fear of Happiness Scale (FHS; Joshanloo 2013a; Joshanloo et al. 2014). The five-item scale captures the stable belief that happiness is a sign of impending unhappiness. The measure is shown to be reliable (Joshanloo 2013a) and has been used and validated across multiple national groups and countries and considered to have good statistical properties (Joshanloo et al. 2014, 2015). Examples of the items include, “I prefer not to be too joyful, because usually joy is followed by sadness.” Cronbach’s alphas in the current study were .74, .80, .81.

The Fragility of Happiness Scale (Joshanloo et al. 2014, 2015). The four-item scale captures the belief in the fleetingness of happiness and is rated on a 7-point scale. The scale has been used, validated and understood as having a constant meaning across multiple national groups and countries and considered to have good statistical properties (Joshanloo et al. 2014, 2015). Item examples include, “Something might happen at any time and we could easily lose our happiness.” Cronbach’s alphas in the current study were .81, .83, .86.

Brief Version of the Santa Clara Strength of Religious Faith Questionnaire (SCSRFQ; Plante et al. 2002). The SCSRFQ is a shorter version of the original scale featuring five items to measure the strength of religious faith. It is considered valid and reliable (Chronbach Alpha = .95), with the shortened version considered as effective as the original. An example of the items includes, “My religious faith impacts many of my decisions.” Cronbach’s alphas in the current study were .85, .88, .88.

7 Results

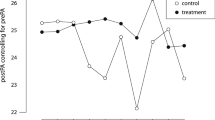

In order to examine if post-intervention levels of wellbeing, fear of happiness, and fragility of happiness differed between the intervention and control group, we conducted a series of ANCOVAs using the first two assessments, excluding the 3-month follow-up (see Table 3 for detailed statistics). Pre-intervention scores were used as a covariate in all analyses. With regard to wellbeing, analyses revealed that at the end of the 14-week Happiness 101 program, affect balance was higher (d = 0.23) and eudaimonic wellbeing was significantly higher in the intervention group (d = 0.40). Scores on the measures of satisfaction with life, flourishing, and overall mental health were not significantly different between the groups at post-intervention. With regard to attitudes towards happiness, at post-intervention, the intervention group reported significantly lower levels of fear of happiness (d = 0.47) and of believing that happiness is fragile (d = 0.23). No difference in religious faith was evidenced between the groups at post intervention.

We ran a second set of ANOCOVAs using pre-intervention scores of the dependent variables, age, gender, and pre-intervention scores of religious faith as covariates. For the most part, effect sizes did not differ significantly utilizing these additional covariates. The one exception to this was affect balance, with significance level changing from p = .080 to p = .051. However, effect size differed only by .03.

We conducted a series of paired t-tests to examine differences in wellbeing and attitudes towards happiness within the intervention group at pre, post, and 3-month follow-up time points, excluding the control group (see Table 4 for detailed statistics). All measures of wellbeing were significantly higher at post-intervention compared to pre-intervention (affect balance: d = 0.30, satisfaction with life: d = 0.33; flourishing: d = 0.19, eudaimonic wellbeing: d = 0.24, overall mental health: d = 0.20). Further, significant gains in levels of affect balance and satisfaction with life from pre-intervention were maintained at the 3-month follow-up (ds = 0.21, 0.21 respectively). Compared to pre-intervention, fear of happiness was significantly lower at post-intervention (d = 0.36) as was believing that happiness is fragile (d = 0.36). These significant differences were maintained at the 3-month follow-up (d = 0.28, d = 0.47). No significant differences in religious faith were evidenced within the intervention group across the three measurement times. Although significance from pre- to post-intervention was marginally higher for religious faith, the effect size was small (d = 0.10).

8 Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that learning about positive psychology concepts and using PPIs resulted in boosts to both hedonic and eudaimonic well-being (as assessed by a variety of measurement scales) from pre- to post-intervention, and sustained gains in affect balance and life satisfaction at the 3-month mark. Further, greater affect-balance and eudaimonic wellbeing scores relative to a control group at 3-month post-intervention were also observed. Our results are consistent with previous studies where gains were maintained over time (Duckworth et al. 2005; Gander et al. 2016; Lambert D’raven et al. 2015). Moreover, effect sizes for change in well-being and attitudes towards happiness (ds from 0.19 to 0.47) were within the range, and for the most part at the high end, of the average effect size for PPIs (ds from 0.20 to 0.34, Bolier et al. 2013).

Further, this study realized important reductions in the belief in the fear of happiness, as well as the fragility of happiness, in the intervention group at post-intervention which were maintained at the 3-month follow-up. Reductions in these beliefs were not observed in the control group and can, thus, be attributed in part to engaging in PPIs as well as learning about positive psychology concepts in general. This is in line with Gander et al.’s (2016) suggestion that greater benefits are found using this two-pronged method rather than merely targeting specific interventions in isolation, as is commonly the case in other PPI studies. Yet, it is unknown whether it was the positive psychology information, the experience of PPIs, or the combination thereof which caused these reductions. Future studies are needed to tease apart these aspects. It is important to note that, to our knowledge, our study is the first to show that the belief in the fear and fragility of happiness (Joshanloo et al. 2014, 2015) can be affected in response to interventions. Moreover, as noted in the introduction, although some cultural and religious beliefs frame happiness in a negative light, our findings suggest that receiving instruction in the science of wellbeing and experiencing its effects can reduce attitudes of fear and fragility of happiness, without diminishing levels of religiosity.

In fact, the reduction in the endorsement of fear and fragility beliefs might have in turn contributed to the gains observed in well-being as a result of the intervention. Research on fear and fragility beliefs indicate that holding these beliefs is associated with lowered hedonic and eudaimonic well-being across cultures (Agbo and Ngwu 2017; Joshanloo et al. 2014, 2015). In particular, if these beliefs are accompanied by high levels of pessimism, they may come to have an even stronger negative impact on well-being (Joshanloo et al. 2017). That is, these beliefs may accompany or even lead to generalized unfavorable expectancies, such as the ideas that happiness is not achievable, out of control, or not worthy to pursue. Such a mindset may demotivate the person and generate feelings of inadequacy to make positive changes in the self and life in general (Joshanloo 2017). In sum, we speculate that the reduction in fear and fragility of happiness may have contributed to the gain in well-being in the present study. Furthermore, although fear and fragility beliefs have not been explicitly targeted in the intervention, we speculate that contents related to optimism and internal locus of control might have been largely responsible for the reductions in the endorsement of fear and fragility of happiness across the time points.

Yet, what are the ethical and moral considerations of modifying such cultural beliefs, even if wellbeing increases as a result? Arguably, most PPI studies have been conducted in the West where more than 90% of the research published in positive psychology emerges and positive psychology’s individualistic and democratic outlooks are assumed, influential, and unquestioned (Arnett 2008; Bermant et al. 2011; Christopher and Hickinbottom 2008; Giacaman et al. 2010; Joshanloo 2013b). As individuals increase focus on their individual happiness and utilize these Western-originating PPIs, will they become less collectivistic and more individualistic over time? Measuring change along the collectivistic-individualistic continuum as a result of PPI use would be an interesting avenue to pursue as well as determining which PPI had the strongest wellbeing effects given that we tested the overall effects of a battery of PPIs.

Finally, while positive psychology focuses on wellbeing, the amelioration of depressive symptoms is also important. Although this was not the focus of the present study, future intervention studies could assess whether negative emotions are reduced via PPI programs such as the Happiness 101 program (Lambert 2009/2012) used in the current study. As many of our participants hailed from countries in which there was, or currently is, civil unrest, incorporating positive psychology interventions to address trauma and other vulnerabilities may be a vital addition in future programs and studies (Brunzell et al. 2016).

9 Limitations

All students had English as a second, third, or even fourth language. While the course had a 1 year English prerequisite, this may nonetheless have posed difficulties in understanding the scale items and program content. The questionnaires were, however, done in class where students could ask for help with terminology. We did not collect data to ascertain year of study of participants. Experiences of first- and final-year students can be notably different; future studies could include this demographic as a possible moderator variable. Ascertaining program of study (data which we did not collect) would have allowed for comparison analyses within the intervention group to explore possible difference in well-being, happiness beliefs, and religiosity across broad academic disciplines (e.g., students in social sciences vs. natural sciences). We recommend that these data be collected in future studies. Students, in contrast with community samples, may also have reported overly positive states of wellbeing at the start of term when new professors and friends create excitement, especially when informed the class project is on happiness. At the same time, wellbeing scores may have been temporarily lower than usual given that end of term deadlines, fatigue, and final exams were looming. Because the happiness program was done for credit, it is unknown whether this affected their results or whether they continued to engage in the interventions outside of class and beyond the term. It is possible that coming from countries like Syria, Iraq, Yemen, Nigeria, Lebanon, etc., and moving to the UAE, the most stable and safe country in the MENA region, could have contributed to the reductions in participants’ beliefs given that happiness is indeed fragile in insecure settings.

10 Conclusion

The growth of wellbeing programs within academia is a welcome development that can, we believe, irreversibly transform the field of education. However, this is currently far from a global norm. We encourage higher educational institutions to take wellbeing as seriously as organizations do, and to track indicators of wellbeing in their student body in order to better understand where to target interventions. We also encourage institutions to consider the cultural and religious implications of using PPI programs, and to develop and validate locally relevant programs and interventions (Lambert et al. 2015). Programs like the Happiness 101 program (Lambert 2009/2012) used in the current study, clearly bring about changes in wellbeing, changes that may have future positive implications for school achievement (Durlak et al. 2011), work (Erdogan et al. 2012), job success (Creed et al. 2002; Neault 2002), and health (Huang and Humphries 2012). But more than anything, such programs offer youth a means to attain the skills to achieve greater versions of themselves, something not currently on offer in most academic institutions.

We also advocate for the inclusion of wellbeing programs that address academic institutions as a whole, in line with Oades et al.’s (2011) advice that a truly positive university must include faculty, administration, the university campus residential setting, and the work environment as targets of interventions. Individual wellbeing gains are difficult to uphold where the broader environment is not the focus of such work. Finally, as this study was the first to show that beliefs of fear and fragility of happiness can be manipulated, and that wellbeing gains are possible in a group of highly diverse international students, we encourage continued inquiry in this direction to achieve a representative global positive psychology (Wong, 2013).

References

Aaker, J., Rudd, M., & Mogilner, C. (2011). If money does not make you happy, consider time. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 21(2), 126–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2011.01.004.

Abu-Raiya, H., Pargament, K. I., & Krause, N. (2016). Religion as problem, religion as solution: Religious buffers of the links between religious/spiritual struggles and well-being/mental health. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care & Rehabilitation, 25(5), 1265–1274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-015-1163-8.

Agbo, A. A., & Ngwu, C. N. (2017). Aversion to happiness and the experience of happiness: The moderating roles of personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 111, 227–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.02.010.

Aknin, L. B., Barrington-Leigh, C. P., Dunn, E. W., Helliwell, J. F., Biswas-Diener, R., Kemeza, I., et al. (2013). Prosocial spending and well-being: Cross-cultural evidence for a psychological universal. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(4), 635–652. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031578.

Aknin, L. B., & Dunn, E. W. (2013). Spending money on others leads to higher happiness than spending on yourself. In J. F. Froh & A. C. Parks (Eds.), Activities for teaching positive psychology: A guide for instructors (pp. 93–98). Washington, DC: APA. https://doi.org/10.1037/14042-015.

Arnett, J. J. (2008). The neglected 95%: Why American psychology needs to become less American. American Psychologist, 63(7), 602–614. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.63.7.602.

Bermant, G., Talwar, C., & Rozin, P. (2011). To celebrate positive psychology and extend its horizons. In K. M. Sheldon, T. B. Kashdan, & M. F. Steger (Eds.), Designing positive psychology: Taking stock and moving forward (pp. 430–438). Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195373585.003.0029.

Bernard, M., & Walton, K. (2011). The effect of You Can Do It! Education in six schools on student perceptions of wellbeing, teaching, learning and relationships. Journal of Student Wellbeing, 5, 22–37. https://doi.org/10.21913/jsw.v5i1.679.

Boehm, J. K., & Kubzansky, L. D. (2012). The heart’s content: The association between positive psychological well-being and cardiovascular health. Psychological Bulletin, 138, 655–691. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027448.

Boehm, J. K., Lyubomirsky, S., & Sheldon, K. M. (2011). A longitudinal experimental study comparing the effectiveness of happiness-enhancing strategies in Anglo Americans and Asian Americans. Cognition and Emotion, 25, 1263–1272. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2010.541227.

Bolier, L., Haverman, M., Westerhof, G. J., Riper, H., Smit, F., & Bohlmeijer, E. (2013). Positive psychology interventions: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. BMC Public Health, 13, 119. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-119.

Brannan, D., Biswas-Diener, R., Mohr, C., Mortazavi, S., & Stein, N. (2013). Friends and family: A cross-cultural investigation of social support and subjective well-being. Journal of Positive Psychology, 8(1), 65–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2012.743573.

Broderick, P., & Metz, S. (2009). Learning to BREATHE: A pilot trial of a mindfulness curriculum for adolescents. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 2, 35–46. https://doi.org/10.1002/yd.20042/pdf.

Brown, K., Ryan, R., & Creswell, J. (2007). Addressing fundamental questions about mindfulness. Psychological Inquiry, 18, 272–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/10478400701703344.

Brunwasser, S. M., Gillham, J. E., & Kim, E. S. (2009). A meta-analytic review of the Penn Resiliency Program’s effect on depressive symptoms. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(6), 1042–1054. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017671.

Brunzell, T., Stokes, H., & Waters, L. (2016). Trauma informed positive education: Using positive psychology to repair and strengthen vulnerable students. Contemporary School Psychology, 20, 63–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-015-0070-x.

Bryant, F., & Veroff, J. (2006). Savoring: A new model of positive experience. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Burton, C., & King, L. (2004). The health benefits of writing about intensely positive experiences. Journal of Research in Personality, 38, 150–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0092-6566(03)00058-8.

Burton, C., & King, L. (2009). The health benefits of writing about positive experiences: The role of broadened cognition. Psychology & Health, 24(8), 867–879. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440801989946.

Carver, C., Scheier, M., & Segerstrom, S. (2010). Optimism. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 879–889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.01.006.

Christopher, J., & Hickinbottom, S. (2008). Positive psychology, ethnocentrism, and the disguised ideology of individualism. Theory & Psychology, 18(5), 563–589. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959354308093396.

Creed, P. A., Patton, W., & Bartrum, D. (2002). Multidimensional properties of the LOT-R: Effects of optimism and pessimism on career and wellbeing related variables in adolescents. Journal of Career Assessment, 10, 42–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072702010001003.

Creswell, J. D., Welch, W. T., Taylor, S. E., Sherman, D. K., Gruenewald, T. L., & Mann, T. (2005). Affirmation of personal values buffers neuroendocrine and psychological stress responses. Psychological Science, 16, 846–851. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01624.x.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York: Harper & Row.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction with Life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13.

Diener, E., Fujita, F., Tay, L., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2012). Purpose, mood, and pleasure in prediction satisfaction judgements. Social Indicators Research, 105, 333–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9787-8.

Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Ryan, K. (2013). Universal and cultural differences in the causes and structure of “happiness”—A multilevel review. In C. Keyes (Ed.), Mental well-being: International contributions to the study of positive mental health (pp. 153–176). Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5195-8_8.

Diener, E., Tay, L., & Myers, D. G. (2011). The religion paradox: If religion makes people happy, why are so many dropping out? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101, 1278–1290. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024402.

Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D., Oishi, S., et al. (2009). New measures of well-being: Flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 39, 247–266. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-2354-4_12.

Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D., Oishi, S., et al. (2010). New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 97, 143–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y.

Dillard, A. J., Schiavone, A., & Brown, S. L. (2008). Helping behavior and positive emotions: Implications for health and well-being. In S. J. Lopez (Ed.), Positive psychology: Exploring the best in people, Vol. 2: Capitalizing on emotions experiences. Westport, CT: Praeger/Greenwood.

Duckworth, A., Steen, T., & Seligman, M. (2005). Positive psychology in clinical practice. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1, 629–651. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144154.

Dunn, E. W., Aknin, L. B., & Norton, M. I. (2008). Spending money on others promotes happiness. Science, 319(5870), 1687–1688. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1150952.

Dunn, E. W., Gilbert, D. T., & Wilson, T. D. (2011). If money doesn’t make you happy then you probably aren’t spending it right. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 21(2), 115–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2011.02.002.

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x.

Erdogan, B., Bauer, T. N., Truxillo, D. M., & Mansfield, L. R. (2012). Whistle while you work: A review of life satisfaction. Journal of Management, 38, 1038–1083. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311429379.

Ferguson, Y. L., & Kasser, T. (2013). A teaching tool for disengaging from materialism: The commercial media fast. In J. F. Froh & A. C. Parks (Eds.), Activities for teaching positive psychology: A guide for instructors (pp. 143–148). Washington, DC: APA. https://doi.org/10.1037/14042-023.

Fischer, P., Sauer, A., Vogrincic, C., & Weisweiler, S. (2010). The ancestor effect: Thinking about our genetic origin enhances intellectual performance. European Journal of Social Psychology, 41(1), 11–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.778.

Fredrickson, B. (2006). The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. In M. Csikszentmihalyi & I. Csikszentmihalyi (Eds.), A life worth living: Contributions to positive psychology (pp. 85–103). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Froh, J., Kashdan, T., Ozimkowski, K., & Miller, N. (2009). Who benefits the most from a gratitude intervention in children and adolescents? Examining positive affect as a moderator. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4, 408–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760902992464.

Froh, J., Sefick, W., & Emmons, R. A. (2008). Counting blessings in early adolescents: An experimental study of gratitude and subjective well-being. Journal of School Psychology, 46, 213–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2007.03.005.

Gable, S. L. (2013). Capitalizing on positive events. In J. F. Froh & A. C. Parks (Eds.), Activities for teaching positive psychology: A guide for instructors (pp. 71–76). Washington, DC: APA. https://doi.org/10.1037/14042-012.

Gable, S., & Reis, H. (2010). Good news! Capitalizing on positive events in an interpersonal context. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 42, 195–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0065-2601(10)42004-3.

Gander, F., Proyer, R. T., & Ruch, W. (2016). Positive psychology interventions addressing pleasure, engagement, meaning, positive relationships, and accomplishment increase well-being and ameliorate depressive symptoms: A randomized, placebo-controlled online study. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, Article 686. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00686.

Giacaman, R., Rabaia, Y., Nguyen-Gillham, V., Batniji, R., Punamäki, R. L., & Summerfield, D. (2010). Mental health, social distress and political oppression: The case of the occupied Palestinian territory. Global Public Health, 6(5), 547–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2010.528443.

Goudie, R., Mukherjee, S., De Neve, J.-E., Oswald, A. J., & Wu, S. (2012). Happiness as a driver of risk-avoiding behavior. The Centre for Economic Performance, Discussion Paper No. 1126. Retrieved March 17, 2014, from http://cep.lse.ac.uk/pubs/download/dp1126.pdf.

Grant, N., Wardle, J., & Steptoe, A. (2009). The relationship between life satisfaction and health behaviour: A cross-cultural analysis of young adults. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 16, 259–268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-009-9032-x.

Green, S., Oades, L., & Robinson, P. (2011). Positive education: Creating flourishing students, staff and schools. InPysch, 16–17, April.

Gulamhussein, Q., & Eaton, N. R. (2015). Hijab, religiosity, and psychological wellbeing of Muslim women in the United States. Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 9(2), 25–40. https://doi.org/10.3998/jmmh.10381607.0009.202.

Hardy, J., Hall, C., & Alexander, M. (2001). Exploring self-talk and affective states in sport. Journal of Sports Sciences, 19, 469–475. https://doi.org/10.1080/026404101750238926.

Helgeson, V. S., Reynolds, K. A., & Tomich, P. L. (2006). A meta-analytic review of benefit finding and growth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(5), 797–816. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.74.5.797.

Hone, L. C., Jarden, A., & Schofield, G. M. (2015). An evaluation of positive psychology intervention effectiveness trials using the re-aim framework: A practice-friendly review. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(4), 303–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.965267.

Huang, H., & Humphreys, B. R. (2012). Sports participation and happiness: Evidence from US microdata. Journal of Economic Psychology, 33(4), 776–793. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2012.02.007.

Huffman, J. C., DuBois, C. M., Healy, B. C., Boehm, J. K., Kashdan, T. B., Celano, C. M., et al. (2014). Feasibility and utility of positive psychology exercises for suicidal inpatients. General Hospital Psychiatry, 36(1), 88–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.10.006.

Huppert, F., & Johnson, D. (2010). A controlled trial of mindfulness training in schools: The importance of practice for an impact on well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5, 264–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439761003794148.

Huta, V., & Waterman, J. (2014). Eudaimonia and its Distinction from hedonia: Developing a classification and terminology for understanding conceptual and operational definitions. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15, 1425–1456. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9485-0.

Johnson, K. J., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2005). “We all look the same to me” Positive emotions eliminate the own-race bias in face recognition. Psychological Science, 16, 875–881. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01631.x.

Joshanloo, M. (2013a). The influence of fear of happiness beliefs on responses to the Satisfaction with Life Scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 54(5), 647–651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.11.011.

Joshanloo, M. (2013b). A comparison of Western and Islamic conceptions of happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(6), 1857–1874. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-012-9406-7.

Joshanloo, M. (2016). Self-esteem in Iran: Views from antiquity to modern times. Middle East Journal of Positive Psychology, 2(1), 22–41. Retrieved from https://middleeastjournalofpositivepsychology.org/index.php/mejpp/article/view/45.

Joshanloo, M. (2017). Mediators of the relationship between externality of happiness and subjective well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 119, 147–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.07.017.

Joshanloo, M., Lepshokova, Z. K., Panyusheva, T., Natalia, A., Poon, W. C., Yeung, V. W., et al. (2014). Cross-cultural validation of the fear of happiness scale across 14 national groups. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 45(2), 246–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022113505357.

Joshanloo, M., Park, Y. O., & Park, S. H. (2017). Optimism as the moderator of the relationship between fragility of happiness beliefs and experienced happiness. Personality and Individual Differences, 106, 61–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.10.039.

Joshanloo, M., & Weijers, D. (2013). Aversion to happiness across cultures: A review of where and why people are averse to happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(3), 717–735. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9489-9.

Joshanloo, M., Weijers, D., Jiang, D.-Y., Han, G., Bae, J., Pang, J., et al. (2015). Fragility of happiness beliefs across 15 national groups. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16, 1185–1210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9553-0.

Joshanloo, M., Wissing, M. P., Khumalo, I. P., & Lamers, S. M. A. (2013). Measurement invariance of the Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF) across three cultural groups. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(7), 755–759. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.06.002.

Judge, T. A., Piccolo, R. F., Podsakoff, N. P., Shaw, J. C., & Rich, B. L. (2010). The relationship between pay and job satisfaction: A meta-analysis of the literature. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77, 157–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2010.04.002.

Kahler, C. W., Spillane, N. S., Day, A., Clerkin, E. M., Parks, A., Leventhal, A. M., et al. (2014). Positive psychotherapy for smoking cessation: Treatment development, feasibility, and preliminary results. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 9, 19–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2013.826716.

Kashdan, T. B., Biswas-Diener, R., & King, L. A. (2008). Reconsidering happiness: The costs of distinguishing between hedonics and eudaimonia. Journal of Positive Psychology, 3, 219–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760802303044.

Kashdan, T. B., & Nezlek, J. B. (2012). Whether, when, and how is spirituality related to well-being? Moving beyond single occasion questionnaires to understanding daily process. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38, 1526–1538. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167212454549.

Kern, M. L., Waters, L. E., Adler, A., & White, M. A. (2015). A multidimensional approach to measuring well-being in students: Application of the PERMA framework. Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(3), 262–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.93696.

Keyes, C. L. M. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43, 207–222.

Keyes, C. L. M. (2005). Mental illness and/or mental health? Investigating axioms of the complete state model of health. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 539–548. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.73.3.539.

Keyes, C. L. M. (2009). Atlanta: Brief description of the Mental Health Continuum Short Form (MHC-SF). Retrieved from http://www.sociology.emory.edu/ckeyes/.

Keyes, C. L. M., & Annas, J. (2009). Feeling good and functioning well: Distinctive concepts in ancient philosophy and contemporary science. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4, 197–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760902844228.

Khumalo, I. P., Temane, Q. M., & Wissing, M. P. (2012). Socio-demographic variables, general psychological well-being and the Mental Health Continuum in an African context. Social Indicators Research, 105, 419–442. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9777-2.

Kok, B., Catalino, L., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2008). The broadening, building, buffering effects of positive emotions. In S. J. Lopez (Ed.), Positive psychology: Exploring the best of people (Vol. 3, pp. 1–19). Westport, CT: Greenwood.

Kurtz, J. L., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2013). Using mindful photography to increase positive emotion and appreciation. In J. F. Froh & A. C. Parks (Eds.), Activities for teaching positive psychology: A guide for instructors (pp. 133–136). Washington, DC: APA. https://doi.org/10.1037/14042-021.

Lambert, L. (2012). Happiness 101: A how-to guide in positive psychology for people who are depressed, languishing, or flourishing (The facilitator guide). Bloomington, IN: Xlibris Corporation.

Lambert, L. (2016). A new year, a new you: 52 strategies for a happier life! CreateSpace Independent Publishing: Amazon Publishing. Retrieved from https://www.amazon.com/New-Year-You-Strategies-Happier/dp/1543062326.

Lambert D’raven, L., Moliver, N., & Thompson, D. (2015). Happiness intervention decreases pain and depression and boosts happiness among primary care patients. Primary Health Care Research & Development, 16(2), 114–126. https://doi.org/10.1017/s146342361300056x.

Lambert D’raven, L., & Pasha-Zaidi, N. (2014a). Positive psychology interventions: A review for counselling practitioners. Canadian Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy/Revue Canadienne de Counseling et de Psychothérapie, 48(4), 383–408. Retrieved from http://cjc-rcc.ucalgary.ca/cjc/index.php/rcc/article/view/2720.

Lambert D’raven, L., & Pasha-Zaidi, N. (2014b). Happiness strategies among Arab university students in the United Arab Emirates. The Journal of Happiness and Well-Being, 2(1), 1–15. Retrieved from http://www.journalofhappiness.net/volume/volume-2-issue-1.

Lambert, L., Pasha-Zaidi, N., Passmore, H.-A., & York Al-Karam, C. (2015). Developing an indigenous positive psychology in the United Arab Emirates. Middle East Journal of Positive Psychology, 1(1), 1–23. Retrieved from https://middleeastjournalofpositivepsychology.org/index.php/mejpp/article/view/24.

Lambert, L., Passmore, H.-A., & Holder, M. D. (2015b). Foundational frameworks of positive psychology: Mapping well-being orientations. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne, 56, 311–321.

Lamers, S. M. A., Glas, C. A. W., Westerhof, G. J., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2012). Longitudinal evaluation of the Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF). European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 28, 290–296. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000109.

Larsen, R. J., & Eid, M. (2008). Ed Diener and the science of subjective well-being. In M. Eid & R. J. Larsen (Eds.), The science of subjective well-being (pp. 1–16). New York: The Guilford Press.

Lount, J. R. B. (2010). The impact of positive mood on trust in interpersonal and intergroup interactions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98, 420–433. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017344.

Lyubomirsky, S. (2011). Hedonic adaptation to positive and negative experiences. In S. Folkman (Ed.), Oxford handbook of stress, health, and coping (pp. 200–224). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Lyubomirsky, S., Dickerhoof, R., Boehm, J. K., & Sheldon, K. M. (2011). Becoming happier takes both a will and a proper way: An experimental longitudinal intervention to boost well-being. Emotion, 11, 391–402. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022575.

Lyubomirsky, S., King, L. A., & Diener, E. (2005a). The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin, 131, 803–855. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803.

Lyubomirsky, S., Sheldon, K. M., & Schkade, D. (2005b). Pursuing happiness: The architecture of sustainable change. Review of General Psychology, 9(2), 111–131. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.111.

Lyubomirsky, S., & Tkach, C. (2003). The consequences of dysphoric rumination. In C. Papageorgiou & A. Wells (Eds.), Rumination: nature, theory, and treatment of negative thinking in depression (pp. 21–41). Chichester: Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470713853.ch2.

Magyar-Moe, J. L., Owens, R. L., & Conoley, C. W. (2015). Positive psychology interventions in counseling: What every counseling psychologist should know. The Counseling Psychologist, 43, 508–557. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000015573776.

Mills, M. J., Fleck, C. R., & Kozikowski, A. (2013). Positive psychology at work: A conceptual review, state-of-practice assessment, and a look ahead. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 8(2), 153–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2013.776622.

Neault, R. A. (2002). Thriving in the new millennium: Career management in the changing world of work. Canadian Journal of Career Development, 1(1), 11–21. Retrieved from http://cjcdonline.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Thriving-in-the-New-Millennium.pdf.

Nelson, D. W. (2009). Feeling good and open-minded: The impact of positive affect on cross cultural empathic responding. Journal of Positive Psychology, 4, 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760802357859.

Norrish, J. M., Williams, P., O’Connor, M., & Robinson, J. (2013). An applied framework for positive education. International Journal of Wellbeing, 3(2), 147–161. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v3i2.2.

Oades, L. G., Robinson, P., Green, S., & Spence, G. B. (2011). Towards a positive university. Journal of Positive Psychology, 6(6), 432–439. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2011.634828.

Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2008). Positive psychology and character strengths: Application to strengths-based school counseling. Professional School Counseling, 12, 85–92. https://doi.org/10.5330/psc.n.2010-12.85.

Parveen, S., Sandilya, G., & Shafiq, M. (2014). Religiosity and mental health among Muslim youth. Indian Journal of Health & Wellbeing, 5(3), 316. Retrieved from https://www.myresearchjournals.com/index.php/IJHW/article/view/507.

Passmore, H.-A., Howell, A. J., & Holder, M. J. (2017). Positioning implicit theories of well-being within a positivity framework. Journal of Happiness Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017-9934-2.

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (1993). Review of the Satisfaction with Life Scale. Psychological Assessment, 5, 164–172. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.5.2.164.

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (2008). The Satisfaction with Life Scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3, 137–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760701756946.

Plante, T. G., Valleys, C. L., Sherman, A. C., & Wallson, K. A. (2002). The development of a Brief Version of the Santa Clara Strength of Religious Faith Questionnaire. Pastoral Psychology, 50(5), 359–368. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1014413720710.

Priller, E., & Schupp, J. (2011). Social and economic characteristics of financial and blood donors in Germany. DIW Economic Bulletin, 6, 23–30. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10419/57691.

Rao, M. A., Donaldson, S. I., & Doiron, K. M. (2015). Positive psychology research in the Middle East and North Africa. Middle East Journal of Positive Psychology, 1(1), 60–76. Retrieved from https://middleeastjournalofpositivepsychology.org/index.php/mejpp/article/view/33.

Rashid, T. (2015). Positive psychotherapy: A strength-based approach. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(1), 25–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.920411.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141–166. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141.

Ryan, R. M., Huta, V., & Deci, E. L. (2008). Living well: A self-determination theory perspective on eudaimonia. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9, 139–170.

Sahraian, A., Gholami, A., Javadpour, A., & Omidvar, B. (2013). Association between religiosity and happiness among a group of Muslim undergraduate students. Journal of Religion and Health, 52(2), 450–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-011-9484-6.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York, NY: Free Press.

Seligman, M. E. P., Ernst, R., Gillham, J., Reivich, K., & Linkins, M. (2009). Positive education: Positive psychology and classroom interventions. Oxford Review of Education, 35(3), 293–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054980902934563.

Seligman, M. E. P., Steen, T., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist, 60(5), 410–421. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.60.5.410.

Shapira, L. B., & Mongrain, M. (2010). The benefits of self-compassion and optimism exercises for individuals vulnerable to depression. Journal of Positive Psychology, 5, 377–389. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2010.516763.

Sheldon, K. M., Abad, N., Ferguson, Y., Gunz, A., Houser-Marko, L., Nichols, C. P., et al. (2010). Persistent pursuit of need-satisfying goals leads to increased happiness: A 6-month experimental longitudinal study. Motivation and Emotion, 34, 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-009-9153-1.

Sheldon, K. M., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2006). How to increase and sustain positive emotion: the effects of expressing gratitude and visualizing best possible selves. Journal of Positive Psychology, 1, 73–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760500510676.

Shoshani, A., & Steinmetz, S. (2014). Positive psychology at school: A school-based intervention to promote adolescents’ mental health and well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(6), 1289–1311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9476-1.

Sin, N., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2009). Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: A practice-friendly meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65, 467–487. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20593.

Suldo, S., Thalji, A., & Ferron, J. (2011). Longitudinal academic outcomes predicted by early adolescents’ subjective well-being, psychopathology, and mental health status yielded from a dual factor model. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 6(1), 17–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2010.536774.

Tajdin, M. (2015). مفهوم السعادة في الفكر الإسلامي الوسيط: من الفلسفة إلى الدين (The concept of happiness in medieval Islamic thought: From philosophy to religion). Middle East Journal of Positive Psychology, 1(1), 36–44. Retrieved from https://middleeastjournalofpositivepsychology.org/index.php/mejpp/article/view/28.

Tay, L., Li, M., Myers, D., & Diener, E. (2014). Religiosity and subjective well-being: An international perspective. In C. Kim-Prieto (Ed.), Religion and spirituality across cultures (pp. 163–175). New York: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8950-9_9.

Thomas, J., Mutawa, M., Furber, S. W., & Grey, I. (2016). Religiosity: Reducing depressive symptoms amongst Muslim females in the United Arab Emirates. Middle East Journal of Positive Psychology, 2(1), 9–21. Retrieved from https://middleeastjournalofpositivepsychology.org/index.php/mejpp/article/view/41.

Waterman, A., Schwartz, S., Zamboanga, B. Y., Robert, R., Williams, M., Bede Agocha, V., et al. (2010). The Questionnaire for Eudaimonic Well-Being: Psychometric properties, demographic comparisons, and evidence of validity. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5(1), 41–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760903435208.

Waters, L. (2011). A review of school-based positive psychology interventions. The Australian Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 28(2), 75–90. https://doi.org/10.1375/aedp.28.2.75.

Watkins, P. C., Sparrow, A., & Webber, A. C. (2013). Taking care of business with gratitude. In J. F. Froh & A. C. Parks (Eds.), Activities for teaching positive psychology: A guide for instructors (pp. 119–128). Washington, DC: APA. https://doi.org/10.1037/14042-019.

Weiss, L. A., Westerhof, G. J., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2016). Can we increase psychological well-being? The effects of interventions on psychological well-being: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE, 11(6), e0158092. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0158092.

White, M. A. (2016). Why won’t it stick? Positive psychology and positive education. Psychology of Well-Being, 6, 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13612-016-0039-1.

White, M. A., & Waters, L. E. (2015). A case study of ‘The Good School:’ Examples of the use of Peterson’s strengths-based approach with students. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(1), 69–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.920408.

Wong, P. T. P. (2011). Positive psychology 2.0: Towards a balanced interactive model of the good life. Canadian Psychology, 52(2), 69–81. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022511.

Wong, P. T. P. (2013). Cross-cultural positive psychology. In K. Keith (Ed.), Encyclopedia of cross-cultural psychology. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118339893.wbeccp426.

Zemojtel-Piotrowska, M., Piotrowska, J. P., Osin, E. N., Cieciuch, J., Adams, B. G., Ardi, R., et al. (2018). The mental health continuum-short form: The structure and application for cross-cultural studies—A 38 nation study. Journal of Clinical Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22570.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lambert, L., Passmore, HA. & Joshanloo, M. A Positive Psychology Intervention Program in a Culturally-Diverse University: Boosting Happiness and Reducing Fear. J Happiness Stud 20, 1141–1162 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-9993-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-9993-z