Abstract

Drawing on unique survey data for rural Pakistan, we estimate a happiness model to explore to what extent an economic perspective adds to our understanding of subjective wellbeing poverty. The data elicits information on subjective well-being in general and particularly on financial well-being in terms of household’s happiness with the current income or expenditure. We find that the well-being approach closely depicts the idea of well-being poverty in terms of the level education, health and income which matter significantly. Moreover unlike developed nations this study suggests a positive impact of children on well-being and poverty due to their productive contribution. As studies employing good data from developing countries are rare, this paper can potentially make a good contribution to the existing happiness literature, with special reference to Pakistan. Secondly, it brings new and strong empirical evidence to alternative approaches to subjective well-being poverty.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

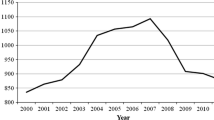

The analysis of happiness is an evolving topic in economics that is increasingly being used to shed light on various socio-economic aspects. While much of the literature presents evidence for developed countries, little economic research has been carried out thus far for the developing world, for instance, on Pakistan—notable exceptions are Kingdon and Knight (2006) on South Africa and Knight et al. (2007) on rural China. With an original data set, this study academically contributes to quality of life (QOL) studies by providing new evidence in rural Pakistan. Pakistan was created with the division of India on the midnight of 14/15 August,1947. Pakistan has been a rather unstable economy since ever with democracy being only a dream till date. In the present times, its mostly highlighted with its nearness and ‘animosity’ with neighboring countries. Pakistan is very much hit by poverty, illiteracy especially among women, and rapid population growth. Pakistan in Asia has much geographical importance because of its strategic location. Firstly, Pakistan has all features of nature like sea, deserts, mountains, rivers. The greatest mountains range of Karakorum is also in Pakistan meeting it with China. Secondly, in this region there are four seasons; summer, winter, autumn and spring which make the climate rich for the agriculture. You find every kind of vegetables, fruits, wheat, minerals etc in Pakistan. Pakistan shares its borders with very prominent countries in the world like India, China, Afghanistan and Iran. Land lock countries do not have route for the transportation of goods by sea therefore, Pakistan also provides sea transportation to some countries. Interestingly, Pakistan is a Muslim country and it is located in the chain of the Muslim countries therefore, it is also known as “Center of Muslim World”.

Using a unique household survey data for rural Pakistan, we present a standard analysis of socio-demographic factors on the subjective well-being (SWB) across the provinces/regions within Pakistan and exploiting the within-country determinants of variation in poverty and subjective dimensions of well-being. More specifically, we estimate the happiness function to investigate to what extent it can measure or can help us to evaluate poverty (in terms of socio-economic factors) on subjective grounds. As poverty is often linked with human development, or the lack of it, this paper intends to have a different take on the matter suggesting that income poverty is only part of the picture. The idea that people’s well-being is not measured by income alone has been at the heart of all the Human Development Reports ever since the first one was produced for the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in 1990 and our paper is in line with that approach.Footnote 1

Subjective well-being (SWB) refers in this context to the happiness i.e. the happiness in terms of socio-economic status, income or expenditure as reported by the household such that poverty is measured in this paper exclusively in terms of the household’s own assessment of well-being without demarcating a standard poverty threshold. This methodological twist of investigating poverty in purely subjective terms obviously raises the question whether well-being is a viable complementary measure to the conventional metric. Whilst conventional poverty measures are defined by income or consumption levels falling below a line set by the World Bank (typically 1 USD per day), we instead intend to explore a more SWB approach to poverty. We do so because in a liberal and democratic spirit, we place a value on the individuals’ own evaluation of their well-being, which underlies much of what we refer to as SWB poverty. Pakistan has been chosen as the underlying country in the sample for the following reasons, firstly, because in third world countries like Pakistan economic satisfaction matters a lot for fulfillment of basic needs and survival, secondly, because of data reasons and last but not the least, it is first ever study on Pakistan on subjective wellbeing and poverty related issues. However, similar measures have actually been used in the dimensional analysis of SWB by Perz (2001) and Sutherland et al. (2004) for Brazil and Guatemala, respectively.

Unlike Kingdon and Knight (2006), apart from analyzing the holistic concept of well-being (i.e. overall well-being), we particularly resort to the economic concept of well-being (i.e. financial well-being) to measure well-being poverty—a concept which seems meaningful with economic reasoning, as one would expect households in developing countries to feel strongly about monetary factors.

The economic analysis of psychological aspects such as happiness has increasingly received attention in the recent literature. There are several studies (see for example Blanchflower (2008) and the references therein) that try to establish a relationship between happiness and different socio-economic variables such as age, gender, income, employment, marital status, etc. to investigate the degree of households’ happiness with their current situation.

The purpose of this paper is to link happiness with demographic as well as socio-economic variables. In particular, we want to investigate whether concepts from the economics of happiness can indeed be used in development economics to employ the SWB approach to poverty as suggested by Kingdon and Knight (2006). We shall do so by estimating a comprehensive model for rural Pakistan. We shall argue that subjective approach indeed offers a sensible complementary approach to conventional measurement techniques in development economics, distinguishing between different measures of poverty matters and should always be considered to ensure robustness, given the self-assessment nature of such a metric. Even using a broad set of conventional socioeconomic data may not reflect well people’s subjective perceptions of their poverty. Ravallion and Lokshin (1999) examine the determinants of subjective economic welfare in Russia, including its relationship to conventional objective indicators. For data on subjective perceptions, they use survey responses in which respondents rate their level of welfare from poor to rich on a nine-point ladder. As an objective indicator of economic welfare, they use the most common poverty indicator in Russia, in which household incomes are deflated by household-specific poverty lines. They found that current household income does not explain well self-reported assessments of whether someone is poor or rich. Expanding the set of variables to include incomes at different dates, expenditures, educational attainment, health status, employment, and average income in the area of residence doubles explanatory power. Controlling for income, healthier, better educated and employed adults perceive themselves to be better off. In contrast, the unemployed assess their well-being as lower. Income also matters. Controlling for income and other factors, living in a richer area lowers perceived well-being. White et al. (2012) locates SWB within psychological wellbeing, happiness and QOL studies more broadly. It argues for attention to concepts, not just techniques, and more engagement with social and political perspectives. It draws on empirical research in Zambia and India to show that context matters and qualitative research is needed to complement quantitative measures of wellbeing. It also suggests that happiness is far from the only way to measure SWB. To our knowledge, there is no comparable adaption of the economics of happiness to exclusively rural areas of Pakistan. We therefore believe that this paper fills an important gap in the literature and may well inspire further research on other developing countries with similar socio-economic features.

This paper is structured as follows. Section 2 lays the necessary ground for the further analysis. We develop the notion of well-being in terms of financial well-being and present some stylised facts from the happiness literature. We outline the survey design and present descriptive statistics of the SWB measures in Sect. 3. We investigate the SWB approach applied to the data for rural Pakistan to evaluate poverty and its different components in Sect. 4. Section 5 analyses components of financial well-being metric to assess poverty. Section 6 discusses the results, comparing the given measures of SWB poverty. Section 7 concludes.

2 Some Stylised Facts and Basic Concepts

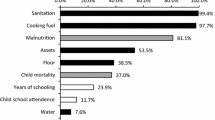

There are numerous conventional measures of poverty in monetary terms. One may construct a so-called poverty line and then measure the distance of a household’s income from a certain reference threshold, typically defined in a particular social context. The World Bank defines poverty in absolute terms suggesting that any income in terms of Purchasing Power Parity below a certain subsistence level classifies households as being “poor”. Rather than considering income, one may also categorise poverty by the uses of income, particularly focusing on consumption. Either way, the conventional poverty metric in the development studies literature suggests the presence of a straightforward and quantifiable method of assessing a household’s economic situation. We believe, however, that the issue of poverty has more dimensions to it: what really matters is not how households may be classified in monetary or purchasing power terms but rather the household’s self-reported degree of well-being. For instance, McGregor and Sumner (2010) argue that human wellbeing can be conceived of in terms of the interplay of three dimensions: the material, the relational and the subjective (also referred to as perceptual). If the notion of wellbeing is reversed to explore the problem of how poverty is generated and reproduced, we find that conventionally it has been understood in terms of material deprivation; latterly the social exclusion and capital literatures have emphasized the importance of relationships; and here a third dimension of subjective experiences and feelings is added to the framework. Studies of development and poverty that have closely engaged with the reality of people’s day-to-day lives have long pointed out that people’s own aspirations and experience of life matter in how they conceive of and struggle for wellbeing (Lewis 1996) and (Appadurai 2004). The Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) of Alkire and Santos (2010) is a recent addition.Footnote 2

The measurement of SWB poverty is by its very nature closely related to the assessment of happiness as also brought forward by Kingdon and Knight (2006). It is still generally acknowledged that increase in wealth, income or goods generally set the conditions for greater well-being and happiness. Infact, income and wealth are related to many positive goals in life: wealthy people are generally more educated, have better health and longer life spans and so forth. It should follow that richer people are substantially happier than others. Another reason for studying economic wealth and welfare is the commonsense conviction that it is very hard to be happy and run a good life in extreme poverty (Bruni and Porta 2005). SWB is typically measured by means of an ordinal scale, where a higher value indicates a higher level of individual’s happiness (Blanchflower and Oswald 2004).

SWB poverty can be measured along two dimensions. First, one may simply resort to the more holistic notion of happiness which encompasses overall well-being. Higher income (and hence less poverty in the conventional sense) should cet. par. induce households to feel happier; although effects are likely to occur at a diminishing rate (Frey and Stutzer 2002). Analysing happiness may thus be considered as a well-being metric to assess poverty. This approach is flexible enough to also measure poverty in more broader terms for instance by considering capabilities poverty in line with the ideas of Sen (1983, 1993).Footnote 3 Second, one may exclusively assess financial well-being by simply asking how satisfied households feel about their incomes and expenditures.

To appreciate the subsequent estimation results in a broader context, it may be helpful to first discuss some stylised facts from the happiness economics literature. Based on US and European panel data, those may be summarised—at least for industrialised countries—as follows (Blanchflower 2008): (1). Well-being depends positively on these controls; e.g. (a) being female, (b) married couples, (c) age (U-shaped behaviour), (d) level of education, (e) active religious involvement, (f) level of health, (g) level of income, (h) regular sexual engagement, (i) monogamy, (j) being childless. (2) Well-being is decreasing among people with the following characteristics; e.g. (a) newly divorced (or separated), (b) adults in their mid to late 40s, (c) unemployed, (d) immigrants and ethnic minorities, (e) commuters, (f) people with poor health, (g) less educated, (h) poor, (i) sexually inactive, (j) having children.

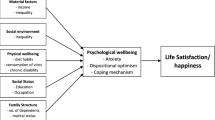

As this list of stylised facts reveals, next to microeconomic factors, perceived happiness is influenced by several variables that are more of a socio-economic nature such as age, sex, marital status, health status, education, social capital, religion, as well as social and political institutions (Helliwell 2002). Psychologists and sociologists thus seem to rightly focus on the possible influence of personality-related factors (such as optimism, self-esteem and perceived personal control) in conjunction with socio-demographic factors, when studying why people are happy or unhappy.

The stylised facts moreover suggest that well-being may be best thought of as an “umbrella concept” capturing various aspects of a person’s life, including both social and financial aspects. Given that in the developing world poverty generally encompasses all these aspects, we feel it is reasonable to use those insights from this strand of the literature to construct an alternative, more subjective poverty metric which more closely reflects the specific socio-economic context.

3 Data

3.1 Research Design

Our analysis is based on a survey of households in rural Pakistan conducted in 2008. The dataset comprises all four provinces of Pakistan: Punjab, Sind, the North Western Frontier Province (NWFP) and Baluchistan. To ensure representativeness, we decided to sample households in ten districts (i.e. roughly one tenth of the total number of districts) across the country (stratified sampling). Based on population figures, we allocated the number of districts across the provinces as follows: four districts from Punjab, three from Sind, two from NWFP and one from Baluchistan. The selected districts in Punjab are Attock, Layyah, Rahimyarkhan and Sahiwal; Badin, Mirpurkhas and Thatta in Sind; Dir and Malakand in NWFP and Kalat from Baluchistan. Those districts were selected for various reasons. First, they are geographically in a range that offered easy access without raising security concerns for the interviewers compared to further remote areas. Second, these districts paint a representative picture of the socio-economic environment in rural Pakistan. Due to the geographic scope of the districts, great care has been taken, where necessary, in sampling households from villages which are reasonably far away from major cities such as Lahore in Punjab, Karachi in Sind, Peshawar in NWFP and Quetta in Baluchistan. Two villages were chosen from each district. Within these predefined strata, households have been selected randomly. Our target was to achieve a total of 30 responses per village, that is 60 households per district, yielding an overall sample size of \(N=600\).

Thus, we have sampled a total of 240 households from Punjab, 180 households from Sind, 120 households from NWFP and 60 households from Baluchistan. Moreover, to ensure a good representation of rural Pakistan, we apply weights to each household with respect to the district of origin as shown in Table 1. All our econometric results are based on that weighting scheme.

The SWB poverty measures is derived from an ordinal scale. The measure of financial wellbeing is based on the following question from the household head or its main member: “How happy are you with your current income or expenditure?”. Answers were recorded on a numerical scale ranging from 1 to 4, where 1 is coded as “Not at all happy’’, 2 as “Less than happy”, 3 as “Rather happy” and 4 as “Fully happy” to capture SWB poverty. We distinguish between two alternatives: happiness with current income or expenditure; responses for each of the two alternatives were coded according to the aforementioned 1–4 scale. Similarly, the measure of overall wellbeing is based on the following question from the household head or its main member: “How happy are you with your current socio-economic status?”. Answers were recorded on the numerical scale ranging from 1 to 4, where 1 is coded as “Not at all happy’’, 2 as “Less than happy”, 3 as “Rather happy” and 4 as “Fully happy” to capture SWB poverty.

3.2 Descriptive Statistics

Tables 2 and 3 report summary statistics for each of the SWB poverty measures. The overall distribution of the happiness variables in terms of income and expenditure are rather similar with the first two moments of both measures being nearly identical (Table 2). Only few respondents report very high or very low values of the happiness index. Regarding happiness with the current socio-economic status (i.e. overall well-being), the answers are quite dispersed. Most of the responses lie between the two extremes: more than half of the respondents are “not at all satisfied”, whilst one third of the responses can be found on the other extreme of the scale.

Table 3 shows how the happiness index of the SWB poverty measures differs across districts. The Table consistently ranks Punjab as the province, on average, with the highest degree of SWB independently of the measure used. In line with the stylised facts reported above, agricultural employment is highest in that province which contributes to the comparatively elevated happiness in that region.

Given that the subjective poverty measures in terms of income and expenditure are not only based on the same scale but also seem to point in a similar direction, it may be worthwhile to investigate their potential interrelationships further.

Table 4 reports Simple Pearson Correlation Coefficients for the given SWB poverty measures. Indeed, the two measures of financial well-being metric we consider are strongly and positively correlated. We see that a high degree of happiness regarding income goes hand in hand with a high happiness with expenditures (correlation of 0.94). Moreover, both measures correlate with the overall well-being metric essentially in the same way (correlations of 0.81, each). We therefore consider the financial well-being measures as alternatives for evaluating SWB poverty in the subsequent estimations of our well-being model.

4 Subjective Well-Being and Poverty

4.1 The Model

The model we use to evaluate SWB poverty is a straightforward application from the happiness literature, where our unique dataset allows for a rather nuanced consideration of the different potential determinants of SWB poverty. As the findings summarised in Sect. 2 suggest, happiness is best thought of as a function of various socio-economic factors. In particular, we estimate a SWB function for rural Pakistan of the following form:

The regression Model (1) implies that well-being is not simply a binary case but is measured in terms of the ordered categories (1–4) introduced above. We employ an ordered probit (oprobit) model of random-effects type of specification that is widely used to analyse discrete data of this type. Our framework is based on an underlying latent model with single index function and constant thresholds. The control variables included are sex, age, education, number of children, employment status, the household’s monthly nominal income (in absolute terms) expressed in natural logs, marital status, the overall family’s health position and the regional background of household i,Footnote 4 where the corresponding \({\beta }\) represents the vector of coefficients of the dummy variables. More specifically, potential gender differences are captured by means of a dummy, where \({ sex}\) is 1 if the respondent/household’s head is male and 0 otherwise. Similarly, \({ unemployment}\) takes the value of 1 if the head of the household is unemployed and 0 otherwise. As for the marital status, living as a married couple implies a value of 1 and 0 otherwise (e.g. living in divorce or widowhood). Age effects, as usual, are allowed to be non-linear. We moreover constructed a health index to evaluate the general health status, where a higher value refers to a higher level of health. The index is based on the following response from the household’s head: “During the last 12 months, how would you assess the health status of your household?”. The answers included: excellent, good, fair, poor, very poor. The answers were then mapped correspondingly onto dummy variables which may be translated into the health index as follows: 4, 3, 2, 1 and 0 for excellent, good, fair, poor and very poor health status, respectively. The excluded category is being in excellent health condition indicated by an index value of 4—our baseline case. In a similar fashion, the region variable refers to three mutually exclusive dummies for respondents living in Punjab, NWFP and Sind, respectively. The baseline category here corresponds to households living in Baluchistan.

Several studies on the economics of happiness add the number of children to the list of explanatory variables in the happiness equation as done for instance by Angeles (2009), Blanchflower (2008) and Clark et al. (2008). However, the empirical evidence is inconclusive. While some authors (Tella et al. 2003; Alesina et al. 2004) find a negative or, respectively, no effect (Clark (2006)), others (Stutzer and Frey (2006)) detect a positive effect of having children at home on overall household’s happiness. Only few papers account for the individual characteristics of the households. Frey and Stutzer (2000), for example, using Swiss household survey data of 1992, find that having children has no effect on the happiness of married couples but a sizable (and negative) impact on single parents. We therefore consider this a crucial aspect to be explored in more detail also for developing countries.

Moreover we impose dummies on the respective number of children per household. In particular, the impact of the number of children on well-being in (1) is captured by \(\beta _5\). We created six dummies in total to separate the cases when one, two, three, four, five, six, seven or more children are present in a household.Footnote 5 We chose households with seven (or more) children as the reference group. Note that children are here defined as individuals aged less than 16 years who live with their parents.

The convention in the happiness economics literature is to define happiness as overall well-being. We first estimate Model (1) with the overall well-being metric as dependent variable and use those results as benchmark. Table 5 gives an overview of the results which may be considered the relevant baseline . The marginal effects for Model (1), using overall well-being metric are given in Table 7. Our findings largely confirm the literature on the determinants of happiness. As expected, well-being depends on gender, education, family size, unemployment, income, health and region. To take an example, the probability of being happy increases with an increasing family size, income or educational achievements.Footnote 6 On the other hand, being a male, unemployed or having a low health profile lowers one’s chance of being satisfied. We furthermore observe that well-being is region-dependent. Relatively speaking , living in Punjab indicates an elevated chance of being happy compared to Sind.Footnote 7

Stutzer and Frey (2002) argue, well-being from an economic perspective tends to be strongly driven by health and monetary factors. Age is another important determinant of well-being. However, the role of that variable is not so straightforward to assess for several reasons. The notion of well-being, after all, may change its connotation with varying age. All these factors are controlled for in our specified well-being functions.

5 Assessing Financial Well-Being

In this Section we test whether income remains significant for the financial well-being metric, using Model (1). Since overall well-being is a rather “soft” concept, it seems more straightforward to use subjective categories which focus more on financial terms.Footnote 8

Table 8 shows the results of the ordered probit regressions, using financial wellbeing metric that can be compared with the baseline results (or the stylised facts) from the happiness literature. The results suggest that male are less likely to be happy with their finances (both in income and expenditure terms) compared to female households. Education increases the probability of financial well-being, particularly in terms of happiness with income. We find that financial well-being is a positive function of education. Furthermore, households having more children are more likely to be financially satisfied compared to households with less or fewer children. As expected, a higher income increases the likelihood of financial well-being and vice versa. Similarly, a higher level of health index ensures a higher level of financial well-being. Regarding regional effects, families in Punjab are most likely to be satisfied with their income and expenditure compared to the other provinces.

Table 9 shows the marginal effects resulting from ordered probit regressions based on Model (1), using financial well-being (i.e. happiness with income or expenditure) as response variable. Furthermore, “happiness with income” and “happiness with expenditure” should be considered here as two separate dependent variables rather than interaction term or something else. According to Table 9, being a male increases the probability of being observed in the lower financial well-being categories (1 and 2), and makes it less likely to be in the higher categories (3 and 4). A large family size is beneficial in terms of financial well-being of a household. Compared to the reference category of seven or more children, a small family of one to three children reduces the chances of a household of being in the higher categories of financial well-being (3 and 4), whilst increasing the likelihood of reporting the lower outcome (2). Similarly, households with lower health outcomes are more likely to be part of the lower financial well-being category (2), while in this case chances of being observed in the higher response categories (3 and 4) are lower. Higher income leads to higher financial outcomes even on pure subjective grounds. For instance, higher income increases the likelihood of being in the higher categories (3 and 4) of financial well-being and at the same time decreases the probability of being in the lower response categories (i.e. 1 or 2). Similarly, higher education ensures higher financial well-being regarding income/expenditure; for instance, education increases the likelihood of being in the higher well-being category (3) and decreases the probability to be observed in the lower category (2). As far as regional effects are concerned, we find that compared to other provinces, being in Punjab increases the chances to be observed in the higher categories of financial well-being (i.e. 3 and 4), whereas it reduces the chances of being in the lower categories of financial well-being (i.e. 1 and 2). In other words, households in Punjab are most likely to be satisfied with their income or expenditure compared to the families living in the other provinces.

Summing up, we see that using this metric, income does matter also on subjective grounds. Estimates are significantly positively associated with the corresponding measure. Closely related to higher income levels is the degree of schooling in the developing world. Indeed, the variable capturing years of education is significantly positively associated with the subjective poverty measures, all other things held constant. Similarly, a higher health index and an increased number of children also seem to be positively associated with the household’s reported financial well-being. According to our results, financial well-being appears to be U-shaped in age. The estimated turning point corresponds to the age of 55 years. This is similar to Easterlin (2006) who also reports evidence for a U-shaped relationship between financial well-being and age in the US. Such a pattern, however, cannot be confirmed for the case at hand on purely statistical grounds. Given the limited public provision of social security (for instance, pensions, old age benefits, etc.) in Pakistan, one would expect an inverted U-shaped relationship between these two variables.

6 Results and Discussion

Overall, comparing the given measures of SWB poverty, a somewhat consistent picture seems to emerge: We may conclude that income, the level of education, health and the number of children matter the most both in econometric and economic terms. Particularly a large family size seems to be vital which appears to confirm the notion of having children as insurance mechanism in developing countries. In areas such as rural Pakistan children are integrated in the family life early on. Many of them contribute considerably to the overall household income already at a young age. In line with this anecdotal evidence, our empirical results suggest that the number of children is one of the major determinants of SWB poverty in rural areas.

Our results are in line with several other studies of comparable scope. Knight et al. (2007), for example, analyse national household survey data on SWB in rural China also suggest that happiness increases with a higher level of education, income or health, respectively. Furthermore, they found that happiness is U-shaped in age. Similarly, Easterlin (2006), based on data from General Social Surveys from 1973–1994, finds that both health and financial well-being in the US follow a U-shaped pattern in age. This would imply that well-being falls with rising age, up to a particular turning point and then starts rising again.

In contrast, it is generally believed in the developing world that elderly persons become increasingly less happy “by nature” not only because their physical and cognitive capacities deteriorate, but also due to psychological factors such as the increasing likelihood of suffering from depression as well as due to poor social security systems in place especially for the older citizens. Like the results for rural China, the US or many EU countries, our results also seem to support the idea of an U-shaped relationship between age and happiness with a theoretical turning point of 55 years of age. However, on purely statistical grounds, on the other hand, it is not obvious per se whether any relationship exists at all.

From a socio-economic point of view, older people tend to be in poorer health and have lower income which makes them less happy (Stutzer and Frey 2002). While one might expect happiness to be of an inverted-U shape in age, a general relationship between age and happiness seems to be difficult to establish. Indeed, a U-shaped age effect on happiness has been challenged on empirical grounds.Footnote 9 The age-happiness pattern is found to differ across countries and time periods. The overall empirical evidence appears blurred at best and it thus seems difficult to draw any robust conclusion.

While our baseline results are in keeping with economic intuition, only the level of education, the number of children, income as well as health status and the regional background turn out to be of some statistical meaning. In particular, a large family size seems to be vital for well-being. A higher nominal income (in absolute terms) does seem to significantly improve households’ perceived well-being—a result which seems meaningful with economic reasoning, as one would expect households in developing countries to feel strongly about monetary factors. However, others like unemployment have no effect in pure statistical terms. Guardiola and Garcia-Munoz (2009) from a sample in rural Guatemala found that some indicators such as education and certain livelihoods for instance quality of house and quantity of land they possess are related to perceived basic needs fulfillment in a positive way. Furthermore, they compared subjective poor and income poor and found that income measures overestimate the number of poor households. This makes sense as this measure does not take into account the assets that the household has, like the ability to cultivate its own land and the land it has, which provide him with nurture. This divergence between both measures and the differences on the results of estimating income and basic needs perception induces us to conclude that both concepts are very far to be equivalent.Footnote 10 SWB poverty seems to be a better measure than income poverty, as the former captures all domains of life that the individual considers, and takes into consideration other factors like culture, geographical aspects and psychological aspects. Therefore, SWB approaches seem to work better than the conventional income approaches, because of many reasons previously found in other studies and those found in this paper. Discussion therefore should be centered in subjective approaches rather than in income ones. Thus, our results suggest that well-being is the broader measure which seems to capture reasonably well important aspects of poverty such as income, health and the level of education that matter most in economic and econometric terms.

7 Conclusion

Using unique survey data for rural Pakistan, we have sought to investigate the impact of socio-demographic factors on individual’s self reported well-being in order to evaluate SWB poverty. This is to our knowledge the first study of SWB in this part of the developing world. We estimate a happiness model with categorical variables to evaluate SWB poverty and its different components. Our main contribution is that we focus on happiness model to explore to what extent an economic perspective adds to subjective wellbeing poverty. We intend to challenge the view of poverty being a purely macro-level phenomenon which is based on a conventional nominal income metric. We demonstrate that analysing the issue on a more micro-level allows for a much richer analysis and more differentiated insights.

The strength of this study is our unique micro data set that allows us to study poverty and its various components in subjective terms. The happiness measure used in this study has good reliability; as it has been widely used in previous literature, for instance, an influential work by Perz (2001) and Sutherland et al. (2004) for Brazil and Guatemala, respectively, where similar measures have actually been used in the dimensional analysis of SWB. Notably, it might have an overlap with satisfaction with life scale (SWLS), which is most widely used scale and contains five items (Pavot and Diener 2008). Furthermore, it might be interesting to explore the role of ethnic diversity, physical security and religious identity in relation to well-being outcome reported; an issue we do not tackle here for data reasons. Apart from that, we didn’t focus on conventional poverty metric in order to measure poverty by setting a benchmark i.e. one or two US dollars per day rather we used SWB approach for the said purpose. Further research should be done in order to make a comparative study of the two approaches, in general, and particularly with reference to rural Pakistan.

Our happiness model is general enough to map the different well-being measures capturing SWB poverty and its different components. We find that SWB is the broader measure which seems to capture reasonably well important components of poverty. In particular, income, health and the level of education matter significantly in economic and econometric terms. The notion of well-being in this context encompasses the idea of capabilities poverty. However, the approach here is more general than this as it also incorporates important and often neglected socio-economic factors such as the number of children in a household.

In addition, our results are in line with common findings in the happiness literature: Happiness is higher among rich, educated and healthy households. The influence of income on SWB has been tested in happiness literature (see for example Clark and Oswald 1994; Dynan and Ravina 2007; Guardiola and Garcia-Munoz 2009; Luttmer 2005 and McBride 2001). Some of these works suggest that happiness functions should be dependent not only on absolute income, but also on relative income.

Pakistan shares distinct demographic features with many other developing countries: It is characterised by a large population as well as high population growth and fertility rates. As expected, the socio-economic environment is crucial for explaining perceived poverty. Our analysis suggests a positive effect of the number of children on individual household’s well-being—a novel result which has not yet been established in such a framework. Our findings thus support the notion of children as insurance mechanism in developing economies. For instance, Perz (2001) in his hypothesis suggests that children are in demand by parents because they provide labor needed for early agricultural production and later (at least for the Brazilian Amazon). Similarly, Sutherland et al. (2004) in a study of Guatemala’s Petén, an agricultural frontier, supports the notion that children may be seen as an economic safety net for those who perceive resources to be scarce.

On a more general note, we also try to make the case in this paper that it is not appropriate to measure SWB poverty by income alone. Just as human development encompasses aspects of life much broader than income, so does poverty that should be regarded as consisting of many dimensions. We cannot rely on positive growth effects trickling down by themselves after all. It takes sound government policies and action to ensure that income supports citizens in expanding their choices and to remain in adequate health as well as to obtain education and resources for themselves and for their children—in short, to achieve human development.

The economics of happiness is still in its infancy, yet it seems to offer promising approaches for development studies. This paper is a further contribution to linking these two fields. Ultimately, further ground is yet to be established from which also other development issues may be analysed from a more psychological perspective in conjunction with solid economic underpinnings. It does appear, however, that a SWB perspective contributes to our understanding of poverty.

Notes

In order to simplify concepts, we shall use the terms happiness and subjective well-being (SWB) and life satisfaction interchangeably.

The MPI aims to capture basically the three dimensions of poverty - health, education and standard of living of a household (Alkire 2010).

Sen introduced the capabilities approach to well-being and poverty which sought to emphasize a person’s ability to achieve various valuable functions as part of living and thus focuses more on psychological rather than material deprivation.

The household head or its main member were asked the questions.

There is no household in the sample without any children.

As pointed by Sen (1997), education can be beneficial for an individual by increasing their capabilities: reading, communicating, being able to choose in a more informed way and so on. We include education of the respondent in the model and found that it plays a positive role in household’s perception of well-being.

The linktest for the baseline Model (1), using the overall well-being metric, is statistically insignificant as shown in Table 6 which suggests that there are no omitted relevant variables and that our link function is correctly specified. Seeking to ensure that all models are properly specified, we moreover conducted the linktest (or specification error test) for each of the ordered probit regressions. The idea of the linktest, loosely speaking, is that if the model is properly specified, one should not be able to find any additional predictors that are statistically significant. The variable _hat should thus be a statistically significant predictor since it is the predicted value from the model. This will be the case unless the model is misspecified. On the other hand, if our model is properly specified, _hatsq should not have much predictive power except by chance. Therefore, the linktest is significant for a significant _hatsq. Such a test outcome would usually suggest that either we have an omitted-variable bias or it might be the case that the link function is not correctly specified.

The output reported in Table 8 suggests, the model is properly specified, also in terms of the joint significance of the children dummies.

See Horley and Lavery (1995) and the references therein for details.

References

Alesina, A., Tella, R. D., & MacCulloch, R. (2004). Inequality and happiness: are Europeans and Americans different? Journal of Public Economics, 88, 2009–2042.

Alkire, S. (2010). Multidimensional poverty and its discontents. A paper presented at the EUDN conference, Paris.

Alkire, S., & Santos , M. E. (2010). Acute multidimensional poverty: A new index for developing countries. OPHI working paper series, 38.

Angeles, L. (2009). Do children make us happier? Discussion paper series, University of Glasgow.

Appadurai, A. (2004). The capacity to aspire: Culture and the terms of recognition, culture and public action.

Blanchflower, D. (2008). International evidence on well-being, NBER working paper.

Blanchflower, D., & Oswald, A. (2004). Wellbeing over time in Britain and the USA. Journal of Public Economics, 88, 1359–1386.

Bruni, L., & Porta, P. L. (2005). Economics and happiness—Framing the analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bruni, L., & Porta, P. L. (2007). Handbook on the economics of happiness. Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishers.

Clark, A. E. (2006). Born to be mild? Cohort effects don’t explain why well-being is U-shaped in age. Working paper 35 Paris-Jourdan sciences economiques.

Clark, A. E., & Oswald, A. J. (1994). Subjective well-being and unemployment. Economic Journal, 104, 648–659.

Clark, A. E., Frijters, P., & Schields, M. A. (2008). Relative income, happiness and utility: An explanation for the Easterlin paradox and other puzzles. Journal of Economic Literature, 46(1), 95–144.

Dynan, K. E., & Ravina, E. (2007). Increasing income inequality. External Habits and Self-Reported Happiness, American Economic Review, 96(2), 189–194.

Easterlin, R. (2001). Income and happiness: Towards a unified theory. Economic Journal, 111, 465–484.

Easterlin, R. (2006). Life cycle happiness and its sources: Intersections of psychology, economics, and demography. Journal of Economic Psychology, 27, 463–482.

Frey, B., & Stutzer, A. (2000). Happiness, economy and institutions. The Economic Journal, 110, 918–938.

Frey, B., & Stutzer, A. (2002). What can economists learn from happiness research? Journal of Economic Literature, 40, 402–435.

Guardiola, J., & Garcia-Munoz, T. (2009). Subjective well being and basic needs: Evidence from rural Guatemala. Granada: University of Granada.

Helliwell, J. F. (2002). How’s life? Combining individual and national variables to explain subjective well-being, Economic Modelling, 20, 331–360.

Horley, J., & Lavery, J. J. (1995). Subjective well-being and age. Social Indicators Research, 34, 283–286.

Kingdon, G. G., & Knight, J. (2006). Subjective well-being poverty vs. income poverty and capabilities poverty? Journal of Development Studies, 42(7), 1199–1224.

Knight, J., Song, L., & Gunatilaka, R. (2007). Subjective well-being and its determinants in rural China. Discussion paper series University of Oxford no. 334.

Lewis, O. (1996). The culture of poverty, urban life: Readings in urban anthropology.

Luttmer, E. F. P. (2005). Neighbours as negatives: Relative earnings and well-being. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120(3), 963–1002.

McBride, M. (2001). Relative-income effects on subjective well-being in the cross-section. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 45, 251–278.

McGregor, A., & Sumner, A. (2010). Beyond business as usual: What might 3-d wellbeing contribute to mdg momentum? IDS Bulletin, 41(1), 104–112.

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (2008). The satisfaction with life scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3, 137–152.

Perz, S. (2001). Household demographic factors as life cycle determinants of land use in the amazon. Population Research and Policy Review, 20(3), 159–186.

Pradhan, M., & Ravallion, M. (2000). Measuring poverty using qualitative perceptions of consumption adequacy. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 82(3), 462–471.

Ravallion, M., & Lokshin, M. (1999). Subjective economic welfare. World Bank—Development Research Group (DECRG); National Research University HigherSchool of Economics.

Rojas, M. (2004). Well-being and the complexity of poverty. Tokyo: United Nations University, WIDER.

Rojas, M. (2008). Experienced poverty and income poverty in Mexico: A subjective well-being approach. World Development, 36(6), 1078–1093.

Sen, A. (1983). Poor, relatively speaking. Oxford Economic Papers, 35, 153–169.

Sen, A. (1997). Editorial: Human capital and human capability. World Development, 25(12), 1959–1961.

Sen, A. K. (1993). The quality of life. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stutzer, A., & Frey, B. (2002). Happiness and Economics. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Stutzer, A., & Frey, B. S. (2006). Does marriage make people happy or do happy people get married? The Journal of Socio-Economics, 35, 326–347.

Sutherland, E., Carr, D., & Curtis, S. (2004). Fertility and the environment in a natural resource dependent economy: Evidence from petén, guatemala. Población y Salud en Mesoamérica, 2(1), 1–14.

Tella, R. D., MacCulloch, R. J., & Oswald, A. J. (2003). The macroeconomics of happiness. Review of Economics and Statistics, 85, 809–827.

White, S., Gaines, S., & Jha, S. (2012). Beyond subjective well-being: A critical review of the stiglitz report approach to subjective perspectives on quality of life. Journal of International Development, 24(6), 763–776.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Luis Angeles, Sai Ding, Richard Harris, Alexander Kadow, Philippe LeMay-Boucher and seminar participants at the University of Glasgow for helpful comments. I am very grateful to the sample households for their patience and cooperation in data collection. The financial support of the Higher Education Commission (HEC) of Pakistan is acknowledged. All remaining errors are my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Weighting Matrix

See Table 1

.

Appendix 2: Tables

See Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9

.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shams, K. Developments in the Measurement of Subjective Well-Being and Poverty: An Economic Perspective. J Happiness Stud 17, 2213–2236 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9691-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9691-z