Abstract

Subjective well-being has been studied by social scientists for decades mostly in developed countries. Little is known about determinants of subjective well-being in developing countries and more particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Using 2005–2008 World Values Survey (n = 1,533) this study adds to existing literature on well-being in developing countries focusing on Ghana. The paper explores the predictors of two measures of subjective well-being—happiness and satisfaction in life at micro-level in Ghana. The analyses are divided into two main sections. The first part describes the distribution of happiness and satisfaction in life among Ghanaians. The second section elucidates factors influencing the selected measures of subjective well-being separately. The data reveal that both happiness and life satisfaction among Ghanaians are shaped by multitude of factors including economic, cultural, social capital and health variables. Relatively, perceived health status emerged as the most salient predictor of both measures of well-being. Besides religiosity, all the religion variables emerged as significant predictors of how Ghanaians appraise their own well-being. Equally, income, ethnicity and social capital variables emerged as predictors of happiness and life satisfaction at micro-level in Ghana. Policy implications of the findings are discussed alluding to multidimensional approach to well-being promotion in the country. The outcome of the study also establishes the fact that factors predicting subjective well-being at the micro level vary in SSA context compared to the developed world.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Increasingly, there is acceptance in quality of life studies that it is possible for a person to be materially well-off and at the same time be dissatisfied with his or her life circumstances (Rojas 2007). The notion that well-being transcends material wealth is not new. Aristotle (2009: 24), in Politics (350 BC), may have been the first to suggest that making wealth the main object of household management serves the “intent upon living only, and not upon living well”. Affirmation that well-being transcends objective measures is popularizing the subjective component of well-being in quality of life studies (Widgery 1982, 2004; Campbell et al. 1976; Andrews and Withey 1976; Bradburn 1969). This is evidenced in the number of academic journals, books, and conferences devoted to the concept.

The interest in SWB is gaining momentum because of possible policy uses of information from studies on how individuals appraise their own life circumstances. Findings from SWB studies can facilitate comparison of needs of different groups and inform policy targets, resources allocation, and thereby minimize social exclusion (Carr et al. 1996). In lieu of the virtues associated with SWB, collecting information about how people feel about their own life circumstances has gained political attention and acceptance in developed countries. For instance, in November 2010 the newly elected British government announced that in addition to traditional data such as income levels or fear of violent crimes it will start measuring national happiness. In the same year, in Canada, the Atkinson Foundation released a Canadian Index of Well-being that focused primarily on non-monetary aspects of well-being (Brooker and Hyman 2010). Along the same line, in 2009, the European Commission and OECD initiated the project Beyond GDP that set similar goals.

Despite its acceptance as a valuable tool in the assessment of quality of life at the micro-level (Schimach and Diener 2003; Cummins et al. 2002), the precise definition of SWB and how to measure continue to be a source of debate (see Liao et al. 2005 for review). Although definitions vary, SWB is portrayed as a measure that attempts to capture the overall sense of well-being, including happiness and satisfaction in life as a whole and other domains of life (see Veenhoven 1991). SWB generally seeks to capture non-economic or non-material dimensions of human life which are not tapped by objective measures of well-being. It is broad and subjective, rather than specific and objective in outlook (McGillivray and Clark 2006). Psychologists allege that SWB reflects complex judgments of individuals’ overall well-being that are based on an integration of self-knowledge regarding many domains of psychological, social, and physical functioning (Diener et al. 1999). Three main approaches to the measurement of SWB can be discerned from the literature. First, “evaluative method” requires respondents to make an appraisal or cognitive reflection of their life such as satisfaction in life (Diener 1994). The second approach, called the “experience (or affect) method”, seeks to assess the emotional quality of an individuals’ experience in terms of the frequency, intensity and type of affect or emotion at any given moment, for example, happiness, sadness, anxiety or excitement (Hicks 2011). Third is the “eudaimonic approach” and it is based on the theory that people have underlying psychological needs for their lives to have meaning, to have a sense of control over their lives and to have connections with other people (Ryff 1989).

The subjective nature of SWB measures has prompted questions about their validity and reliability across cultures. It is not clear whether survey questions such as, ‘Taking your life as a whole, would you consider it very happy, somewhat happy or not happy at all?’ can capture satisfaction in life and happiness on a global scale, or even if the concept of ‘satisfied in life’ is understood in the same way across different languages, cultures and socio-economic contexts (Wierzbicka 2004) (let alone in the same cultural context) (Corsin-Jimenez 2007). Despite the criticisms, a number of validity, reliability, and comparison studies have confirmed that subjective measures of well-being are comparable to, if not better than objective measures of well-being (see Kahneman and Krueger 2006). The advantage of using subjective measures in the assessment of well-being is well articulated by Sarracino (2008: 460) as follows:

respondent’s assessment of their own welfare can highlight factors that are not adequately captured by income measures, including real and perceived insecurity of rewards and incentives systems adapting to structural changes, the state of essential public services (educations, health, crime prevention), and norms of fairness and justice.

A convincing argument for employing subjective measures in measuring quality of life in well-being studies is articulated by Costanza et al. (2008: 1) as follows:

Subjective indicators of QOL gain their impetus, in part, from the observation that many objective indicators merely assess the opportunities that individuals have to improve QOL rather than assessing QOL itself. Thus economic production may best be seen as a means to a potentially (but not necessarily) improved QOL rather than an end in itself. In addition, unlike most objective measures of QOL, subjective measures typically rely on survey or interview tools to gather respondents’ own assessments of their lived experiences in the form of self-reports of satisfaction, happiness, well-being or some other near-synonym. Rather than presume the importance of various life domains (e.g., life expectancy or material goods), subjective measures can also tap the perceived significance of the domain (or “need”) to the respondent.

Review of the literature reveals that almost all the studies on SWB are based on data from developed countries (see Frey and Stutzer 2002 for detailed review). Little is known about SWB in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Considering the myriad of quality of life challenges facing the region, it stands to reason that objective measures of well-being should be given attention over subjective ones. However, a number of events taking place in the region make an understanding of various aspects of SWB critical.

Majority of countries in SSA are going through economic reforms, democratization, upswing in incidence of chronic diseases and HIV/AIDS, ageing, increasing poverty, and political instability which are directly and indirectly informed by and related to individuals’ evaluation of their own well-being (Fidrmuc 2000; Hayo 1999; Böhnke 2004; Gurr 1970; De-Graft Aikins 2005; WHO 2005). For instance, democracy and the free market economic system have been touted as the solution to SSA problems and a prerequisite to securing a peaceful and well-functioning society (see Fidrmuc 2000, 1999). Evidence abounds that people’s individual sense of well-being is a fundamental instigator of instability (Böhnke 2004; Gurr 1970). In a region where survival is threatened by ethnic fragmentation (Easterly and Levine 1997) and poverty, economic reforms and democratic dispensations are likely to become a mirage without a positive sense of well-being among the people. Additionally, economic and political reforms take time to yield dividends at the micro-level. To avert the short-term (transitional period) instability which normally follows reforms there is a need to develop, what the development literature terms, pro-poor policies (see World Bank 1999). For such programs to achieve maximum results they need be informed by how people feel about their own well-being.

All in all, as the various countries in SSA pursue policies and reforms which are normally perceived as Draconian, it is prudent that SWB be accorded a prominent place in any poverty abatement and well-being enhancement programs in the region. The first step towards successful integration of SWB into any program in SSA is to come to terms with factors shaping individuals’ outlook about their life circumstances (Böhnke 2005). Therefore, an exploration of factors influencing people’s assessment of their own well-being as attempted in this paper is a valid and important aspect of quality of life studies in SSA. This paper contributes to a growing body of work within well-being and quality of life research that is increasingly concerned with SWB in developing countries.

1.1 Subjective Well-Being in Ghana: Issues and Challenges

Post-independence centralized economy, political instability, and mismanagement in Ghana resulted in almost total collapse of the country in the early 1980s. This debacle precipitated the adoption of democratic governance and a free market economy. The acceptance of democracy was predicated on the theoretically assumed link between democratization, free market economy and enhanced quality of life in society (Esping-Andersen 1990; Di Tella et al. 2001). Political scientists have exhorted the idea that a democratic system with its built-in checks and balances tends to formulate and institute social policies that trigger enhancement in the quality of life of its’ citizens. As Esping-Andersen (1990) has pointed out, a democratic state is by necessity preoccupied with the production and distribution of social well-being. Economists have also theorized that a capitalist free market economic system can effect change in well-being either directly, by transforming the welfare of people or indirectly, by creating the appropriate environment for institutions to work and raise welfare at the individual level (Di Tella et al. 2001).

Operating from these assumed virtues of democratic governance and the capitalist system, Ghana has adopted free market liberalization policies and embraced democratic dispensations for decades now. Macroeconomic indicators suggest that due to the economic reforms of the 1980s Ghana has considerably transformed the economy (Aryeetey and Kanbur 2005). After decades of economic reforms and institutionalization of democratic principles, Ghana has become a peaceful and stable democracy, making good progress toward its goal of becoming a middle-income country by 2020. With economic growth rates consistently topping 6 % over recent years, Ghana is being hailed as an emerging African economic success story. Since 1990, Ghana has been able to reduce the number of Ghanaians living in extreme poverty by almost 50 %. Poverty has declined from 36.5 to 18.2 % between 1991 to 2000 (Ghana Statistical Service 2000a). Despite all the positive macroeconomic indicators, there is an increasing concern over social problems ranging from fear of crime (Adu-Mireku 2002), high unemployment especially among the youth (Baffoe-Bonnie and Ezeala-Harrison 2005; Boateng and Ofori-Sarpong 2002), limited access to drinkable water, increasing cases of material hardships (Addai and Pokimica 2012), limited access to quality education and health care to relatively high poverty levels in the country (Ghana Statistical Service 2000a). Notwithstanding the remarkable reduction in poverty, 30 % of Ghanaians still live on less than US$1.25/day. Poverty continues to pose a threat to the well-being of the most vulnerable in the country-rural majority, women, children, the youth, farmers, uneducated, and disable persons. Even more disturbing is the regional disparities in levels of poverty in the country. The three Northern Savannah regions continue to bear the bulk of the poverty burden in the country. Poverty levels in these regions ranged between 52 and 88 % as of 2000, far above the national average of 18.2 % (Ghana Statistical Service 2000b).

The general well-being of Ghanaians is also being challenged by burden of care from high incidence of chronic diseases. Available data reveal that as of 2003 four conditions—stroke, hypertension, diabetes and cancer—were among the top ten causes of death in each regional health facility in the country (see Adjei-Mensah and de Graft 2010). In the face of absence of infrastructure to care for people with chronic illness, victims of chronic illness have to endure a number of emotional, psychological, physical and mental challenges (De-Graft Aikins 2005). Evidence cogently confirms that the well-being of caregivers is not exempted from the stresses that tend to accompany chronic illness. For instance, Read et al. (2009) has reported that in Ghana increasing dependence on family and significant others for medical care normally creates emotional conflict and breakdown in marital and intimate relationships, as well as family abandonment, all of which put the mental health of caregivers and their families to test. The community reactions to diseases such as cancers, epilepsy, schizophrenia and psychosis have huge negative impact on well-being of victims and their family members. In a society where etiology of disease continues to be imputed to evil spirits (Twumasi 1972, 1975), chronic illness and especially mental disorders tend to be perceived with scorn and are stigmatized leading to ostracism of patients and their family members (Allotey and Reidpath 2007; De-Graft Aikins 2006).

Further, well-being among Ghanaians is challenged further by demographic shifts and forces of modernization. Demographic profile of the country shows that about 7 % of the country’s total population is 60 years or over and projections are that this number will increase to 15 % by 2020 (World Bank 2000). Typical of most African societies, most of the elderly population in Ghana resides in rural settings and the family is their only source of support (Apt 1996; Ardayfio-Schandorf 1994). In the face of increasing urbanization, international migration, and modernization, there are fewer kin members to attend to day-to-day upkeep of the elderly population in various communities (Aboderin 2004a, b; Bigombe and Khadiagala 2003; Bradley and Weisner 1997; Apt 1996). This is putting more stress on the few extended family members in the rural areas. The stress from the ageing population is compounded by dwindling resources in support of the aged. Due to absence of formal social security for the majority of the elderly population, remittances from urban migrants have been one of the main sources of support for the elderly in rural Ghana. With the rising unemployment and unfavorable economic conditions among urban wage earners in the country (Boateng and Ofori-Sarpong 2002) it is increasingly becoming difficult to remit resources to the aged relatives in rural areas. The ageing of the population is adding to the family’s care burden problems and hence undermining the well-being of family members. In light of the economic, demographic, epidemiological, social, and psychological challenges that Ghanaians have to endure on a daily basis many believe the quality of life at micro-level in the country is waning (Gyimah-Boadi and Ansah 2003: 5).

The impetus for this study is fuelled by the fact that sustaining the economic and political gains the country has registered will require pursuing the same reforms and policies which have not been able to improve living conditions for the most vulnerable Ghanaians. Equally disturbing is the harsh reality the burden of care from chronic illness, incidence of poverty, ageing of the population alongside crime and unemployment are likely to get worse in Ghana in the foreseeable future. The main task confronting the government now is how to keep the momentum of the reforms going and at the same time tame the challenges to well-being. In the short-term, the answer lies in designing poverty abatement programs often called “pro-poor” programs in development literature (World Bank 1999). The key to the success of such programs is that they must be based on factors shaping people’s evaluation of their own conditions. It is therefore imperative that policy makers come to terms with factors influencing SWB at the micro-level.

The need to focus on SWB measures in Ghana is reinforced by the increasing realization that in order to survive psychological and economic challenges, one must have resiliency culture or culture that shows the trait of resiliency. The only way to build and sustain a culture of resiliency is to recognize strengths that keep communities and individuals satisfied and unified (Donnellan et al. 2009). One way to recognize these strengths is to investigate the determinants of how people feel about their own well-being in the country

Review of the literature shows that whereas the distribution and determinants of objective measures of well-being such as Gross Domestic Product (GDP)-have been well scrutinized in Ghana (see Aryeetey and Kanbur 2005), the same level of investigation cannot be alleged when we focus on SWB in the country. With the exceptions of research undertaken by Pokimica et al. (2012), Addai and Pokimica (2010), Tsai and Dzorgbo (2012), and Arku et al. (2008) studies on SWB in Ghana are highly limited. Of even more concern is the fact that our knowledge in this field (specifically in Ghana) is sporadic due to conceptualization and measurement problems. Almost all the SWB studies based on data from Ghana tend to employ proxies in their measurement of SWB. For instance Pokimica et al. (2012) and Addai and Pokimica (2010) measured SWB in terms of how individuals assess their living standards or condition rather than how they feel about their overall life. Likewise, Tsai and Dzorgbo (2012) studied avowed happiness and sense of security, but, only among heads of households in the context of remittances and reciprocity. Arku et al. (2008) is the only study that measured general sense of well-being directly. However, considering that the study focused on three municipalities in the Ho Volta region, generalizing the findings for the whole country is a bit problematic.

This study is motivated by the need to overcome measurement and related weaknesses inherent in existing SWB research from Ghana reviewed for this paper. Unlike earlier studies based on Afrobarometer and Core Welfare Indicators questionnaires, this study uses the World Values Survey (WVS) which has direct instruments on measures of overall well-being. Utilizing two measures of SWB—happiness and satisfaction in life—a modest attempt is made at capturing the distribution of Ghanaians’ sense of happiness and satisfaction in life and elucidate factors that inform how one assesses his or her own happiness and satisfaction in life. Since this study is based on a large nationally representative sample and transcends measurement and related problems inherit in previous inquiries, findings from this work are likely to have greater authenticity when compared to prior works. This paper is therefore one of the first, if not the first, to truly enhance our comprehension on SWB in Ghana.

2 Data and Measures

We examined predictors of well-being in Ghana by analyzing data from the 2005–2008 wave of World Values Survey. The survey was conducted in several countries and focused on a variety of socio-cultural, economic, and political factors. As in other participating countries, the Ghana sample is nationally representative of 1,534 men and women aged 16 years and older. The data collection in Ghana occurred between February and April 2007 through face-to-face interviewing of individual respondents selected from households using the Kish Grid. The interviews were conducted in five local languages: Ga, Dagbani, Ewe, Twi, and Hausa. Among other things, the survey collected detailed information about the respondent’s views about democracy, their participation in the electoral process, governance, livelihood, well-being, economic concerns, social capital, crime and conflict, and perception about national identities.

In addition, detailed information on the respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics, including their age, education, place of residence, religious involvement, religiosity, region of residence, ethnic background, and marital status were also collected. It is the later questions, plus those dealing with well-being, that we use in this study. Subjective well-being is measured by self—reported assessment of individuals own satisfaction and happiness in life.

3 Analytic Techniques

Analysis was carried out at three stages. The first stage presented a graphical distribution of the well-being measures under observation—happiness and satisfaction in life. The second stage used a non-parametric method (Chi square) to look at the association between the well-being measures and selected independent variables. In the third stage logistic regression equations were used to estimate multivariate models of the odds or the likelihood of a respondent reporting a more satisfied life and greater happiness than a less satisfied life. The model helped to estimate the predictors of various measures of subjective well-being while simultaneously controlling for other measurable factors associated with well-being. The logistic regression model estimates a linear model in the following form:

where pi is the estimated probability of a particular event occurring to an individual with a given set of characteristics Xi; b0 is a constant that defines the probability pi for an individual with all Xi set to zero; b is the estimated coefficients. The ratio pi/[1 − pi] is the odds ratio of respondents with a given set of characteristics reporting better versus worse subjective well-being. The estimate of bi for a particular covariate Xi is interpreted as the difference in the predicted log odds between those who fall within that category of characteristics and who fall within the reference group or omitted characteristic. If each estimated bi is exponentiated (Exp[bi]), the result can be interpreted as giving the relative odds of having better subjective well-being for those individuals with characteristic Xi, relative to those individuals in the reference group. All results of multivariate models are given as the exponentiated coefficients. Considering the number of variables included in the study, four accepted significance levels normally used in social science studies—0.10, 0.05, 01, and 0.001 were used in determining the statistical significance of the various variables in terms of association with and influencing the well-being measures under study—happiness and satisfaction in life. The omnibus test of model coefficient and its equivalent Hosmer–Lemeshow test were reported accordingly. The former was used to examine whether or not the explanatory variables adequately fit the data better, the goodness of fit of the regression model.

3.1 Dependent Variable

We are cognizant of the debate as to the most appropriate way to measure subjective well-being (see George 1981 for detailed discussion). Whereas some researchers advocate for single global measures (Jackson et al. 1986), others espouse the virtues of domain-specific component measures of well-being (Andrews and McKennell 1980). Recent developments in the well-being literature leans more in favor of domain specific measures approach (George 1981: 357). However, given that domain specific measures are absent from our data set, we focus instead on global measures which have been found to give comparable results to domain specific measure.

Generally, two dimensions of global measures of well-being have received considerable scrutiny in the sociological and psychological literature: cognitive and affective (Andrews and McKennell 1980). Affective measures reflect spontaneous responses which are assumed to tap into, mainly, transient assessments and sentiments. On the contrary, indicators of cognitive conditions are thought to capture reflective responses which are based upon implicit comparisons of ideal and real life circumstances and are assumed to be relatively stable over time (George 1981; Diener 1984). While measures of happiness are projected as indicators of affective components of well-being, measures of life satisfaction are viewed as capturing the cognitive aspects of well-being. In this study, both indicators of well-being are measured in terms of the respondent’s own assessment of his or her life satisfaction and happiness. Answers to the question “In general how satisfied are you with life?” are recoded into a binary measure, with 1 = better (including “much better” and “better”) and 0 = worse (combining “same”, “worse” and “much worse”). The specific question asked to capture happiness was as follows, “Taking all things together would you say you are: (1 = very happy to 4 = not all happy)”. Responses to the original question were recoded into a binary value: 1 = happy (including very happy and rather happy) and 0 = not happy (including not happy and not happy at all).

3.2 Predictor/Independent Variables

To assess the relative importance of various variables in predicting the two measures of well-being, theoretically relevant variables pertaining to areas such as perceived health status, culture, demography, socioeconomic status, geography and social capital are utilized in the different multivariate models, based on their availability in the data set (Diener et al. 1999). All of the variables included in the analyses are subsumed under broader categories of: (1) economic factors—relative income and social class, (2) health—self-reported health, (3) geographic—region of residence (North versus South), (4) cultural—ethnicity, and religious affiliation, religious involvement, attendance to religious service and religiosity, (5) social capital—interpersonal trust, institutional trust, civic engagement, freedom of choice, and honesty, and (6) demographic—age, sex, marital status, and education. Certain specific variables are not included in this study because they were not present in the data set. We are cognizant of the fact that there are other measures, such as friendship, mutual assistance, and trustworthiness that have been found to be important in various studies on social capital in Ghana. Unfortunately, most of the salient measures of social capital alluded to in the literature are not in the data set hence their exclusion from the analyses.

Table 1 presents the mean and range of continuous variables used in creating various indices for analysis purposes. The average age of the respondents is 33.89 years.

4 Findings

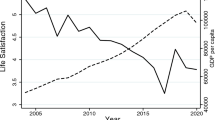

The distribution of satisfaction in life among the respondents is shown in Fig. 1.

Generally it can be said that Ghanaians are satisfied in life. Whereas about 61 % of respondents reported being satisfied and somewhat satisfied in life, only 25 % of Ghanaians indicating that they were not satisfied in life at the time of the survey. Figure 2 shows that about 80 % of Ghanaians reported being very happy and quite happy and only 20 % professed not very happy and not at all happy.

4.1 Bivariate Analysis Results

Table 2 displays percentage distribution of happiness and satisfaction in life (among Ghanaians) by all the variables used in the study except the index ones and age. To show whether the variables are significantly associated with the well-being measures, Chi square coefficients and their significance for each bivariate assessment are presented in Table 2. Ethnicity showed significant association with well-being (χ2 = 18.883, p < 0.001 and χ2 = 45.515, p < 0.001). The data reveal that Akans are happier and more satisfied with life than any other ethnic group in the country followed by the Ga-Adangbe and Ewes. The members of the Other Ethnic groups were the least satisfied and happy at the time of the survey. Analysis of the data reveals that religious affiliation is significantly associated with satisfaction in life (χ2 = 16.075, p < 0.01) not happiness. A higher proportion of the members of the Protestants/Evangelicals faith professed being happy and satisfied in life as compared to any other religious denomination in the country. Involvement in religion is significantly associated with both measures of well-being (χ2 = 26.566, p < 0.01 and χ2 = 5.892, p < 0.05). Over 70 % of religiously active Ghanaians reported being happy and satisfied with life compared to their inactive counterparts. Attendance at religious service is found to be significantly associated with both happiness and satisfaction in life (χ2 = 10.061, p < 0.01 and χ2 = 6.626, p < 0.05). While 45 % of Ghanaians who attended religious services regularly reported being happy and satisfied in life, those reporting attendance as once per week or occasionally displayed lower percentages, 39 and 15 % respectively.

Relative income is significantly associated with both happiness and life satisfaction (χ2 = 2.647, p < 0.001 and χ2 = 102.970, p < 0.001). Interestingly, the proportion of low income Ghanaians who reported being happy and satisfied with life is higher than individuals in middle and higher income categories. Along the same line, there is a significant association between social class and well-being measures under study (χ2 = 14.617, p < 0.05 and χ2 = 50.688, p < 0.05). The data displays an inverse relationship between social class and well-being measures under study. The proportion of Ghanaians who indicated being happy and satisfied in life tended to be highest among the lower class, followed by middle, working, and upper classes (in that order). Contrary to expectation, employment status didn’t show significant association with either happiness or satisfaction in life.

The findings reveal that social capital variables are significantly associated with both happiness and satisfaction in life among Ghanaians (χ2 = 2.909, p < 0.10; χ2 = 36.666, p < 0.001 and χ2 = 9.925, p < 0.01; χ2 = 4.639, p < 0.05). For instance, a higher percentage of Ghanaians who value freedom of choice and control (approximately of 80 %) reported being happy and satisfied in life. Only 41 % of Ghanaians who value honesty reported being happy and satisfied in life. The data indicate that gender is neither associated with happiness nor satisfaction in life among Ghanaians at the time of the study. Marital status is significantly related to both measures of well-being among Ghanaians (χ2 = 7.376, p < 0.01; χ2 = 5.059, p < 0.05). Contrary to what marriage and family literature suggests, a higher proportion of married Ghanaians indicated being satisfied in life and happier (52 %) compared to their unmarried counterparts (48 %).

Interestingly, individuals’ sense of happiness in Ghana is significantly related to whether one lives in Southern or Northern part of the country (χ2 = 7.376, p < 0.01). A higher proportion of Ghanaians who live in the North part of the country (almost 58 %) indicated being happy as against 42 % of Southerners. Unlike happiness, place of residence is not significantly related to being satisfied in life. For education, there exists a curvilinear relationship with the measures of well-being. The data showed that while a Ghanaians with no formal education/post education report lower levels of happiness and satisfaction in life, Ghanaians with elementary and high school education report greater being happiness and satisfaction. Self-reported health status is significantly related to both happiness and satisfaction in life. As expected, while 86 % of Ghanaians who reported having better health reported being happy and satisfied in life, only 12 % of the respondents who reported poor health indicated being happy and satisfied in life (χ2 = 137.275, p < 0.001).

4.2 Multivariate Analysis: Logistic Regression Results

Multivariate logistic regressions were conducted to determine utility of economic, social capital, religious, geographic, and demographic variables in predicting the likelihood of being happy and satisfied in life among Ghanaians. In the analyses all the variables were entered using stepwise method. Table 3 presents estimates of the effects of selected predictors on the odds (Exp[B]) of reporting happiness and satisfaction in life among the respondents. The omnibus test of model coefficients, which gives better predictive analysis of individual scores as against the baseline model, reported the following results. The model Chi square for personal happiness is 244.64 and satisfaction in life is 260.88. They both show a Hosmer–Lemeshow test of goodness of fit significance of p < 0.001. By this, we conclude that the overall model with its explanatory predictors has a better fit than a model with no predictions.

4.3 Happiness

Model 1 depicts the odds of reporting being happy versus not being happy. The data reveal that having Akan ethnic background induced higher odds (Exp [B] = 1.975, p < 0.05) of reporting happiness compared to the other Ghanaians. Contrary to expectation, the likelihood of reporting happiness is about 47 % (Exp [B] = 0.526, p < 0.10) and 51 % (Exp[B] = 0.490, p < 0.05) lower for Ghanaians who professed Catholic and Protestant/Evangelical faiths respectively. However, Ghanaians who are actively involved in religion are more than 3 times (Exp[B] = 3.137, p < 0.001) more likely to report being happy as compared to the reference group. Attendance to religious service is statistically significant in shaping sense of happiness. Ghanaians who attended church once a week were approximately 1.5 times (Exp[B] = 1.476, p < 0.10) more likely to report being happy compared to those who attended service occasionally. Contrary to expectation, the importance that individuals attach to religion/religiosity is not statistically significant in influencing happiness among Ghanaians.

As expected, Ghanaians who are in the upper and middle income brackets are respectively 3.251 times (Exp[B] = 3.251, p < 0.001) and 2.1 times (Exp[B] = 2.069, p < 0.001) more likely to report being happy compared to their counterparts in the lower income bracket. However, among middle class Ghanaians, the odds of reporting happiness are approximately 36 % lower (Exp[B] = 0.635, p < 0.05) than those who are in the lower class. Community engagement and honesty are the only social capital variables that show significant relationship with happiness. Ghanaians who are active in their communities are 1.1 times (Exp [B] = 0.109, p < 0.05) more likely to report being happy compared to the reference group. Likewise, the probability of reporting being happy among those who value honesty is approximately 1.5 times (Exp[B] = 1.486, p < 0.001) higher than the reference group. Interestingly, the likelihood of married Ghanaians reporting being happy is 23 % (Exp[B] = 0.771, p < 0.10) lower compared to the non-married. Another surprising finding is that the odds of reporting happiness are 45 % (Exp[B] = 0.551, p < 0.001) lower among Ghanaians who lived in the Southern part of the country compared to their Northern counterparts.

Ghanaians who had elementary education are approximately 45 % more likely to report being happy (Exp[B] = 1.445, p < 0.10) compare to those who had no formal education. It is noteworthy that the singular health related variable in the equation (self-reported health) had the strongest relative effect on the likelihood of reporting being happy. The likelihood of reporting being happy is approximately 4.4 times (Exp[B] = 4.363, p < 0.001) higher among those who perceived their health to be good compared to their counterparts who reported poor health. Together, the predictors accounted for 15–23 % of the variance in happiness (see Table 3 for Cox and Snell and “Nagelkar” R-square). The overall Log-linear ratio of the model for personal happiness is 1,352.28.

4.4 Satisfaction in Life

Just as in happiness, cultural and religious factors emerged as significant predictors of satisfaction in life. The odds of reporting being satisfied in life are 64 % higher among Akans (Exp[B] = 1.640, p < 0.01) in comparison to the reference group. Religious affiliation, involvement, and attendance to service are significant predictors of life satisfaction. Unlike happiness, being affiliated with Catholic faith is not significantly related to satisfaction in life. However, affiliation with Protestant/Evangelical faiths continued to show a negative relationship with satisfaction in life (Exp[B] = 0.594, p < 0.10). Equally intriguing, is the fact that affiliation with Muslim faith shows a positive and significant relationship with satisfaction in life. The odds of reporting being satisfied in life among Muslims is 55 % (Exp[B] = 1.553, p < 0.10) higher than the reference group. The likelihood of reporting being satisfied in life is approximately 56 % (Exp[B] = 1.556, p < 0.10) higher among those who are active in religion in comparison to those who are inactive in their religious activities. The salience of religion in life satisfaction is reinforced by the fact that attendance at religious service at least once a week instigates higher odds of being satisfied in life (Exp[B] = 1.376, p < 0.10).

After the necessary controls, relative income emerged as a significant predictor of satisfaction in life. The probability of reporting being satisfied in life is 2.6 times (Exp[B] = 2.617, p < 0.001) and approximately 2.1 times (Exp[B] = 2.083, p < 0.001) higher among Ghanaians belonging to the upper and middle class respectively compared to the lower class. Likewise, compared to those in the lower class, the working class are 56 % (Exp[B] = 1.564, p < 0.01) more likely to report being satisfied with life. The data reaffirm the potency of social capital variables in shaping one’s sense of life satisfaction. For instance, the likelihood of reporting being satisfied with life is higher for Ghanaians who engage in community activities (Exp[B] = 1.095, p < 0.05) and those who favor freedom of choice and control in one’s life (Exp[B] = 2.090, p < 0.001). Another variable that significantly predicts satisfaction in life is how Ghanaians perceive their own health status (self-rated health). Ghanaians who rated their own health as good are 2.6 times (Exp[B] = 2.611, p < 0.001) more likely to report being satisfied in life. All in all, 16–21 % of variance in satisfaction in life is explained by the variables included in this study (see Table 3 for Cox and Snell and “Nagelkar” R-square). The overall Log linear ratio of the model for satisfaction of life is 1,766.58.

5 Discussion

In the present study we attempted to elucidate factors predicting two measures of well-being—happiness and satisfaction in life at the micro-level in Ghana. Comparatively, the data revealed that while the level of happiness among Ghanaians was reasonably high, they are relatively less satisfied with life. The disparity between the affective measure—happiness and the cognitive measure—life satisfaction may be attributable to the culture of Ghanaians and the socioeconomic realities of life in the country. Ghanaians are generally easy going people and tend to exude a positive sense of happiness. However, the high sense of hopelessness measured in terms of poverty, unemployment, high incidence of crime, and material deprivations that have engulfed the country (see Addai and Pokimica 2013) may be undermining peoples’ overall sense of satisfaction in life.

Both bivariate and multivariate results indicated that ethnicity is an important predictor of both measures of well-being among Ghanaians. Similar findings have been reported by Addai and Pokimica (2010) in an earlier study about ethnicity and economic well-being in Ghana. The Akans higher odds of reporting happiness and satisfaction in life may be attributable to the relative advantage and position the group enjoys in the country in terms of access to social amenities and economic opportunities. Another possible reason may be due to the social organization of the group. The Akans matrilineal kinship system is noted for its strong kin network and support. This group tends to put the welfare of all extended family members at the center of family affairs.

The bivariate analysis indicated that Ghanaians who are in the lower class category professed to be happier than their counterparts in the middle class; as well as the upper class, which was surprisingly found to be the least happy group. Equally revealing is the finding that a higher proportion of Ghanaians who lived in the Northern part of the country, which is relatively socioeconomically undeveloped (Ewusi 1976), professed being happier than their Southern counterparts. These findings may be attributable to what is termed in measurement literature as “reporting heterogeneity” that different socioeconomic groups tend to perceive their well-being differently even when their environments are the same (see Subramanian et al. 2009, Butler et al. 1987 for review).

The multivariate analyses showed that except for religiosity, all the religious measures in the study emerged as significant predictors of well-being among Ghanaians. Generally, religion is assumed to influence well-being through various ways: by providing members a sense of belonging and serving as a source of social support, providing individuals’ lives meaning and purpose, and encouraging people to lead healthier lifestyle (Ellison et al. 1989). The data revealed that religious affiliation was both a blessing and a curse as far as happiness and satisfaction in life were concerned. Interestingly, with the exception of Muslim faith, all the other religious faiths in the study (Catholic and Protestant/Evangelical) tend to undermine happiness and satisfaction in life among Ghanaians in comparison to their Traditional and None religious counterparts. Similar findings have been reported in earlier studies based on data from Ghana (Pokimica et al. 2012).

The data showed that involvement and attendance at religious services is positively related to well-being, even with the effects of numerous demographic, socioeconomic factors, denominational affiliation, and personal religiosity held constant. The importance of religious involvement and service attendance in predicting well-being indicate that it is the engagement in religious activities which contributes to well-being, and not just affiliation. In Ghanaian society the strong relationship between religious engagement and well-being may be explained in the context of the important role religion is assuming in the country. Due to the failure of government to meet the needs of the population, coupled with the breakdown of the traditional family structure, churches are gradually emerging as the most reliable source of social support and well-being. Churches are providing schools, hospitals, orphanages, universities, insurance and credit facilities and funeral services to their members. Increasingly they are providing institutional settings and regular opportunities for social interaction between people of like minds and similar values, which transcends family and ethnicity. Religious involvement has therefore emerged as the most important medium of nurturing friendship and social networks with direct bearing on social capital attributes such as trust (Addai et al. 2013) and well-being of Ghanaians (Pokimica et al. 2012).

Religiosity was neither related to happiness nor satisfaction in life at both bivariate and multivariate levels of analyses. This casts doubt on the general hypothesis that personal religiosity buffers the effect of stress in Ghanaian context. Nonetheless, a note of caution is in order here. These insignificant findings may reflect the limited variation in the religiosity variables. Background diagnostics of the variable (not shown here) shows that a large majority of the respondents rated themselves “very religious” leading to possibly inaccurate results. It is possible that research using more discriminating and detailed indicators of religiosity could yield different results.

The data lend credence to the assertion that richer members of a society are generally happier than their poorer counterparts. The general proposition in mainstream economics is that, other things being equal, greater income will increase welfare by providing access to more and superior goods and services, better health, quality education and the like. However, an increase in relative income is expected to induce improvement in standards of living and it is likely that consumption norms may change, causing material aspirations to shoot upward. Thus, people will judge their well-being based on whether their income allows them to fulfill their material aspirations. This is more likely to be the case in poor countries like Ghana. The link between income and well-being needs to be reviewed with caution as studies have establish that at a certain point higher income may not necessarily increase happiness and satisfaction in life (Graham and Pettinato 2002). One interesting finding in this study is the positive relationship between the working class background and satisfaction in life. The rationale behind this finding may be contested in the context of aspiration theory (Hayo and Seifert 2003). The economic and political transformations in Ghana may have resulted in high aspirations for the working class. Despite the challenges in the country, the working class members may be hopeful of their future and senses improvement in their lives.

Social capital captured by community engagement showed a positive relationship with well-being. Ghanaians who were active in their communities (signing petitions, joining boycotts, attending peaceful demonstrations, reading newspapers, books, using e-mails, talking to friends, and voting in elections) reported higher odds of being happy and satisfied in life. The relationship between social capital measures and well-being reported in this study may suggest that an increase in relational goods is an important force when it comes to how people appraise their own happiness and satisfaction in life, as suggested by Putnam (2000).

That fact that interpersonal, institutional trust, and civic involvement did not show up as significant predictors of neither satisfaction in life nor happiness is somewhat puzzling, especially in light of previous findings that consistently identify these as important determinants of subjective well-being (Becchetti et al. 2008). Considering the documented evidence of the salience of marriage, trust, and education in well-being studies, the fact that these variables barely register as predictors of happiness and were not significantly related to satisfaction in life is problematic and calls for more study.

The analyses cogently confirmed that the strongest predictor of well-being/happiness and satisfaction in life seems to be how individuals perceive their own health. This finding has been corroborated in earlier studies (Helliwell and Putnam 2004). The relative strength of this variable could suggest that health does actually have an intrinsic value. It may serve as means to other ends such as good job, happy marriage, and others. However, the causal relationship between well-being and health is not straightforward as it is possible that people who are happy and satisfied in life pursue healthier lifestyles and vice versa.

6 Conclusion and Policy Implications

Governments have always been preoccupied with policies and programs that promote better life and improve quality of life for citizens. This is more urgent in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) where the perils of poverty and the HIV/AIDS epidemic pose a real threat to well-being at the micro-level. Despite the fact that an individual’s well-being is highly shaped by what transpires around them, research indicates that individual attributes shape well-being, particularly how people feel about their own lives (Diener et al. 1999). With few exceptions, studies on determinants of SWB are virtually non-existent in SSA. To fill this vacuum we made it our purpose in this paper to assess the factors influencing happiness and satisfaction or subjective well-being at the micro-level.

This study presents cross-sectional evidence of a significant association between cultural, economic, social capital, and health variables with happiness and life satisfaction among Ghanaians. The findings from this study need to be taken with caution due to some limitations. First, methodologically, the cross sectional nature of the data limits one’s ability to assess trends and establish causation between the two well-being measures and the factors included in the study. Secondly, availability of more domain aspects variables of well-being would have shed more light on predictors of SWB. Third, having data on physical health (such as morbidity) and functional limitation variables would have shed more light on our understanding of which aspect of health is germane to well-being. Finally the data also limits our ability to probe the relative importance of internal and external variables in shaping well-being in Ghana. Despite these limitations, there are some important findings with policy implications.

The study reveals that after decades of economic and political transformations, ethnicity continues to be a significant determinant of well-being at the micro-level. The observed relationship between ethnicity and subjective well-being in Ghana is an important finding which demands further research. If studies can give credence to the social organization hypothesis about the association between ethnicity and subjective well-being as suggested in this paper, then policy makers can harness such cultural assets for the stability of the country. Since the Akans form the majority of the population in the country, this is an important finding that merits attention in welfare policy formulation and implementation.

The study convincingly confirmed that religion is a potent force in how Ghanaians perceived their well-being. The findings suggested that religion can be a blessing and curse as far as well-being is concerned. Whereas affiliation with certain religious groups undermined well-being, some instigated higher well-being. Any program that tries to promote well-being needs to pay attention to this variable. Religious-specific programs promoting well-being may be a step in the right direction. The fact that religious involvement and attendance at services are positively related to well-being, makes investing more resources in promoting religious engagement a vital well-being promotion strategy in Ghana. However, to fully reap the dividends of religion for well-being among Ghanaians, researchers need to make sure that they adequately capture the ways different aspects of religion work independently, as well as they interact with one another to affect well-being. So many aspects of religion do not easily lend themselves into quantification and as a result any study that seeks to capture this valuable factor needs to employ both qualitative and quantitative methods. Such an approach would help reduce the risk of reductionism error that tends to characterize most studies on religion.

The salience of self-rated health status in predicting well-being as reported in this study clearly indicates that, if the objective of policymakers is to improve the population’s well-being they should focus on making health a priority. This has implications for research and public policy. For policy makers, the clear message is that there cannot be any meaningful enhancement in well-being without paying attention to how Ghanaians gauge their own health status. Therefore studies on factors influencing self-rated health in the country may help in the formulation of well-being promotion programs. Equally, the charge is for government to commit resources to the health needs of the people.

The significance of social capital in predicting well-being suggests that social capital is a valuable asset which demands serious consideration in Ghana’s well-being strategies. Since the extent to which Ghanaians have trust in the nation’s institutions (a proxy for perceived quality of governance) does not seem to be a significant predictor of well-being, we could assume that this mechanism is simply not plausible in the Ghanaian context. This might be because people feel they have been consistently disappointed with the institutions, and thus have become immune to what is going on in the country. They may have mentally eliminated this variable from their well-being “equation”. Similarly, interpersonal trust did not emerge as a significant predictor of well-being. These findings are not consistent with earlier studies that found trust to be a significant predictor of material deprivation among Ghanaians (see Addai and Pokimica 2012). If we take Ghana to be somewhat representative of the SSA region as a whole, we can conclude that determinants of subjective well-being at the micro-level might well be a bit different for this region than for the much more heavily-researched western world. More empirical work clearly needs to be done in this region if we wish to better understand subjective well-being. However, this study vividly confirms that promotion of well-being in SSA and especially among Ghanaians will require a multidimensional approach. Boosting relative income is important but equally critical is creating an environment where the middle class can achieve their dreams and minimize frustrations, which always serve as a springboard for instability in poor countries. Moreover, cultural and social capital variables need to be accorded serious attention in any well-being promotion effort. The virtue of cultural and social capital factors in well-being promotion is that they would require very limited financial resources.

References

Aboderin, I. (2004a). Decline in material family support for older people in urban Ghana, Africa: Understanding processes and causes of change. Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 59, S128–S137.

Aboderin, I. (2004b). Modernization and ageing theory revisited: Current explanations of recent developing world and historical Western shifts in material family support for older people. Ageing and Society, 24, 29–50.

Addai, I., & Adjei, J. (2013). Predictors of self-appraised health status in sub-Saharan Africa: The case of Ghana. Applied Research in Quality of Life. doi:10.1007/s11482-013-9220-3

Addai, I., Opoku-Agyeman, C., & Ghartey, H. T. (2013). An exploratory study of religion and trust in Ghana. Social Indicators Research, 110(3), 993–1012.

Addai, I., & Pokimica, J. (2010). Ethnicity and economic well-being: The case of Ghana. Social Indicators Research, 99(3), 487–510.

Addai, I., & Pokimica, J. (2012). An exploratory study of trust and material hardship in Ghana. Social Indicators Research, 109(3), 413–438.

Adjei-Mensah, S., & de Graft, Akins. A. (2010). Epidemiological transition and the double burden of disease in Accra, Ghana. Journal of Urban Health Bulletin of the Network Academy of Medicine, 87(5), 879–897.

Adu-Mireku, S. (2002). Fear of crime among residents of three communities in Accra, Ghana. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 43 (2), 72–98.

Allotey, P., & Reidpath, D. (2007). Epilepsy, culture, identity and wellbeing. A study of the social, cultural and environmental context of epilepsy in Cameroon. Journal of Health Psychology, 12(3), 431–443.

Andrews, F. M., & McKennell, A. C. (1980). Measures of cognition and affect in self-reported well-being: Their affective, cognitive and other components. Social Indicators, 8(2), 127–155.

Andrews, F. M., & Withey, S. B. (1976). Social indicators of well-being. New York: Plenum.

Apt, N. A. (1996). Coping with old age in a changing Africa: Social change and the elderly Ghanaian. Brookfield: Averbury Aldeshot.

Ardayfio-Schandorf, E. (1994). Family and development in Ghana. Accra: Ghana Universities Press.

Aristotle. (2009). The politics and the constitution of Athens. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Arku, F. S., Filson, G. C., & Shute, J. (2008). An empirical approach to the study of well-being among rural men and women in Ghana. Social Indicators Research, 88, 365–387.

Aryeetey, E., & Kanbur, R. (2005). Ghana’s economy at half century: An overview of stability, growth and poverty. In E. Aryeetey & R. Kanbur (Eds.), The economy of Ghana: Analytical perspectives on stability, growth and poverty. Oxford: James Currey.

Baffoe-Bonnie, J., & Ezeala-Harrison, F. (2005). Incidence and duration of unemployment spells: Implications for the male-female-wage differentials’. Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 45, 824–847.

Becchetti, L., Pelloni, A., & Rossetti, F. (2008). Relational goods, sociability, and happiness. Kyklos, 61, 343–363.

Bigombe, B., & Khadiagala, G. M. (2003). Major trends affecting families in sub-Saharan Africa. United Nations Division for Social Policy and Development. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/family/Publications/mtbigombe.pdf.

Boateng, K., & Ofori-Sarpong, E. (2002). An analytical study of the labor market for tertiary graduates in Ghana. World Bank/National Council for Tertiary Education and National Accreditation Board Project Report.

Böhnke, P. (2004). Feeling left out: Patterns of social integration and exclusion. In J. Alber, T. Fahey, & C. Saraceno (Eds.), Handbook of quality of life in the enlarged European Union (pp. 304–324). London, New York: Routledge.

Böhnke, P. (2005). First European quality of life survey: Life satisfaction, happiness, and sense of belonging. Dublin: European Foundation for the improvement of living and working conditions.

Bradburn, N. M. (1969). The structure of psychological well-being. Chicago: Aldine.

Bradley, C., & Weisner, T. S. (1997). Introduction: Crisis in the African family. In T. Weisner, C. Bradley, & P. L. Kilbride (Eds.), African families and the crisis of social change (pp. xix–xxxii). Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey.

Brooker, A. S., & Hyman, I. (2010). Time use. A report of the Canadian index of wellbeing (CIW) Toronto.

Butler, J. S., Burkauser, R. V., Mitchell, J. M., & Pincus, T. P. (1987). Measurement errors in self-reported health variables. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 64, 644–650.

Campbell, A., Converse, S. E., & Rodgers, W. L. (1976). The quality of American Life. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Carr, A. J., Thompson, P. W., & Kirwan, J. R. (1996). Quality of life measures. British Journal of Rheumatology, 35(3), 275–281.

Corsin-Jimenez, A. (2007). Culture and well-Being: Anthropological approaches to freedom and political ethics. UK: Pluto Press.

Costanza, R., et al. (2008). An integrative approach to quality of life measurement, research, and policy, S.A.P.I.E.N.S, 1.1/2008, online version, http://sapiens.revues.org/index169.html. Accessed October 2, 2012.

Cummins, R. A., et al. (2002). A model of subjective well-being homeostastis: The role of personality. In E. Gullone & R. A. Cummins (Eds.), The universality of subjective well-being indicators. Boston: Kluver Academic Publisher.

De-Graft Aikins, A. (2005). Healer-shopping in Africa: New evidence from a rural urban qualitative study of Ghanaian diabetes experiences. British Medical Journal, 331, 737.

De-Graft Aikins, A. (2006). Reframing applied disease stigma research: A multilevel analysis of diabetes stigma in Ghana. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 16(6), 426–441.

Di Tella, R., MacCulloch, R., & Oswald, A. (2001). Preferences over inflation and unemployment. Evidence from surveys of happiness. The American Economic Review, 91(1), 335–341.

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 85, 542–575.

Diener, E. (1994). Measuring subjective well-being: Progress and opportunities. Social Indicators Research, 28, 35–89.

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2), 276–302.

Donnellan, M. B., Conger, K. J., McAdams, K. K., & Neppl, T. K. (2009). Personal characteristics and resilience to economic hardship and its consequences: Conceptual issues and empirical illustrations. Journal of Personality, 77(6), 1645–1676.

Easterly, W., & Levine, R. (1997). African’s growth tragedy: Policies and ethnic divisions. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(4), 1203–1250.

Ellison, C. G., Gay, D. A., & Glass, T. A. (1989). Does religious commitment contribute to individual life satisfaction? Social Forces, 68, 100–123.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Ewusi, K. (1976). Disparities in levels of regional development in Ghana. Social Indicators Research, 3(1), 75–100.

Fidrmuc, J. (2000). Political support for reforms: Economics of voting in transition countries. European Economic Review, 44, 1491–1513.

Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2002). Happiness and economics: How the economy and institutions affect well-being. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP.

George, L. K. (1981). Subjective well-being: Conceptual and methodological issues. Inc. Eisdorfer (Ed.), Annual review of gerontology and geriatrics (pp. 345-382). New York: Springer.

Ghana Statistical Service. (2000a). Poverty trends in Ghana in the 1990s. Ghana: Accra.

Ghana Statistical Service. (2000b). Ghana living standards survey: Report on the fourth round (GLSS4). Ghana: Accra.

Graham, C., & Pettinato, S. (2002). Frustrated achievers: Winners, losers and subjective well-being in new market economies. The Journal of Development Studies, 38(4), 100–140.

Gurr, T. R. (1970). Why men rebel. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Gyimah-Boadi, E., & Ansah, K. A. (2003). The growth of democracy in Ghana despite economic dissatisfaction: A power alternation bonus? Afrobarometer. Working Paper No. 28.

Hayo, B., & Seifert, W. (2003). Subjective economic well-being in Eastern Europe. Journal of Economic Psychology, 24, 329–348.

Helliwell, J. F., & Putnam, R. D. (2004). The social context of well-being. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 359(1449), 1435–1446.

Hicks, S. (2011). The measurement of subjective well-being: Paper for the measuring national well-being Technical Advisory Group.

Jackson, J. S., Chatters, L. M., & Neighbors, H. W. (1986). The subjective life quality of black Americans. In F. Andrews (Ed.), Research on the quality of life (pp. 193–213). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan institute for Social Research.

Kahneman, D., & Krueger, B. A. (2006). Developments in the measurement of subjective-being. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(1), 3–24.

Liao, P., Fu, Y., & Yi, C. (2005). Perceived quality of life in Taiwan and Hong Kong: An intra-culture comparison. Journal of Happiness Studies, 6, 43–67.

McGillivray, M., & Clark, M. (2006). Human well-being: Concepts and measures. In M. McGillivray & M. Clarke (Eds.), Understanding human well-being. Palgrave MacMillan: Basingstoke.

Pokimica, J., Addai, I., & Takyi, B. (2012). Religion and subjective well-being in Ghana. Social Indicators Research, 106(1), 61–79.

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone. The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Read, U. M., Adiibokah, E., & Nyame, S. (2009). Local suffering and the global discourse of mental health and human rights: An ethnographic study of responses to mental illness in rural Ghana. Globalization and Health, 5, 13.

Rojas, M. (2007). The complexity of well-being: A life-satisfaction conception and a domains-of-life approach. In I. Gough & A. McGregor (Eds.), Researching in developing countries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 1069–1108.

Sarracino, F. (2008). Subjective well-being in low income countries: Positional, relational and social capital components. Studie Note di Economia Anno XIII, 3, 449–477.

Schimach, U., & Diener, E. (2003). Experience sampling methodology in happiness research. Journal of Happiness Studies, 4(1), 1–4.

Subramanian, S. V., Subramanyam, M. A., Selvaraj, S., & Kawachi, I. (2009). Are self reports of health and morbidities in developing countries misleading? Evidence from India. Social Science and Medicine, 68, 260–265.

Tsai, M., & Dzorgbo, D. S. (2012). Familial reciprocity and subjective well-being in Ghana. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74(1), 215–228.

Twumasi, P. A. (1972). Ashanti traditional medicine and its relation to present-day psychiatry. Transition, 41, 50–63.

Twumasi, P. A. (1975). Medical systems in Ghana: A study in medical sociology. Accra-Tema: Ghana Publishing Corporation.

Veenhoven, R. (1991). Is happiness relative? Social Indicators Research, 24, 1–34. In Wanous J. P. & Hudy M. J. (2001). Single-item reliability: A replication and extension. Organizational Research Methods (4) 361–375, 2001.

Widgery, R. (1982). Satisfaction with the quality of urban life: A predictive model. American Journal of Community Psychology, 10(1), 37–48.

Widgery, R. (2004). A three-decade comparison of residents’ opinions on and beliefs about life in Genesee County, Michigan. In M. J. Sirgy, D. Rahtz, & D.-J. Lee (Eds.), Community quality-of-life indicators: Best cases (pp. 1533–1582). The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Wierzbicka, A. (2004). Happiness in cross-linguistic and cross-cultural perspective. Dædalus, Spring, 34–48.

World Bank. (2000). World development indicators database, July, 2000, The World Bank Group.

World Bank. (1999). Rethinking poverty reduction: World development report 2000/1 on poverty and development. Chapter 4. In Poverty Reduction and the World Bank: Progress on Fiscal 1998. Washington: The World Bank.

World Health Organization. (2005). WHO: Preventing chronic disease. A vital investment. Geneva: WHO.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Addai, I., Opoku-Agyeman, C. & Amanfu, S.K. Exploring Predictors of Subjective Well-Being in Ghana: A Micro-Level Study. J Happiness Stud 15, 869–890 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9454-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9454-7