Abstract

This paper studies the nature of intra-household arrangements in Mexico on the basis of the relationship between a person’s economic satisfaction and her household income. It also studies different theories of the family. The main results support the argument that Mexican families are mostly altruistic and communitarian, with the evidence rejecting a cooperative-bargaining model in Mexican families. Special consideration is given to the situation in low-income families, where marginalization from the household’s economic resources may expose a person to substantially severe economic deprivation. Intra-household arrangements may vary across countries and cultures. Thus, their understanding is crucial for making cross-country comparisons based on household income and per-capita income measures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The literature on household arrangements has stressed that the family is a black box; inside this black box there may be communitarianism, altruism, and cooperation, bargaining and conflict (Bergstrom 1997; Hart 1990; Vogel 2003). This paper deals with the nature of intra-household arrangements and with their impact on the economic satisfaction of household members.

Due to its own nature, the family requires from its members to pool up many economic resources, as well as to specialize in the production of specific tasks.Footnote 1 However, it does not necessarily imply that the economic benefits from resources being pooled up and from specialization are equally distributed among all family members. The distribution of economic benefits does depend on the kind of intra-household arrangement that prevails in the family.

There are different theories regarding intra-household arrangements. Cooperative-bargaining models of the family state that the intra-household distribution of economic well-being depends on the distribution of bargaining power; those members with greater bargaining power do get greater economic well-being. Communitarian models of the family state that intra-household resources are distributed in such a way that all family members do end up having a similar economic well-being. Altruistic models emphasize that some members are willing to sacrifice for the benefit of others; thus, the distribution of economic well-being is not egalitarian, but it does not follow suit the distribution of bargaining power.

The nature of intra-household arrangements in a country is of relevance for the study of economic well-being, as well as for the understanding of economic behavior and for the design of focalized social programs that aim to raise people’s economic well-being. It is a common practice to use household income or household equivalent income as a proxy for the economic well-being of all members in the family. Due to the nature of the family, personal-income figures are of little relevance because, up to a certain degree, personal income is being pooled up and does not indicate a person’s access to economic resources that enhance his/her economic well-being. In addition, personal-expenditure figures are also of little relevance since a large part of household expenditure is made in commodities shared by all household members. Thus, even if it is assumed that economic well-being is closely related to—and can be proxied by—a person’s purchasing power, it would still be impossible to associate a person’s economic well-being to his/her household income unless a specific assumption is made about the distribution of economic benefits within the family.

This paper addresses the issue of intra-household arrangements in the distribution of the economic benefits from a given household income. Following the subjective well-being literature, economic well-being is proxied by an economic-satisfaction variable. The paper studies whether there are differences in the distribution of economic satisfaction across persons on the basis of their breadwinning and family status. In other words, the investigation tests the validity of the hypothesis which states that the relationship between household income and economic satisfaction is the same for all household members, independently of their family status and of their breadwinning status. A communitarian arrangement in the family would imply that all family members get the same economic satisfaction from a given household income, independently of their family and breadwinning status. A cooperative-bargaining arrangement in the family implies that economic satisfaction is distributed in an unequal way among family members, and that this distribution closely follows the intra-household distribution of power; hence, economic satisfaction would be expected to be greater for those members with higher family or breadwinning status. An altruistic arrangement in the family also implies an unequal distribution of economic satisfaction among family members, but this distribution is not related to their bargaining power.

The investigation has a special interest in the study of intra-household arrangements in low-income families, where an unequal distribution of the economic well-being benefits from a given household income may place some family members at serious well-being risks.

The empirical research is based on a large survey applied in south-central Mexico. It is found there is altruistic behavior in low-income Mexican households; while communitarian arrangements do exist in middle and high-income Mexican households. There is no support for cooperative-bargaining arrangements being dominant in Mexican families.

The paper is structured as follows: Sect. 2 introduces the literature on intra-household arrangements. Section 3 presents the database and discusses the construction of a subjective economic well-being indicator, called economic satisfaction. Section 4 deals with what the appropriate household-income variable is. Section 5 studies whether a person’s family status is related to her economic satisfaction; it shows that a person’s household-equivalent income is not a good proxy for her economic well-being due to altruistic behavior, in special in low-income households. Section 6 studies whether a person’s breadwinning status is related to her economic satisfaction; it arrives to similar conclusions than Sect. 5. Section 7 further studies the role of a person’s intra-household bargaining power in her economic satisfaction. Section 8 presents the major conclusions from the investigation.

2 Intra-Household Arrangements and Economic Satisfaction

The family is not only an ancient human institution but it also constitutes a central institution in most social organizations. The family is much more than a group of people sharing a common roof; although its specific foundation may vary across—and even within—countries. Many theories have been proposed to explain the origin and functioning of the family (White and Klein 2007; Smith et al. 2008) and research on the family may require a multidisciplinary perspective (Bengtson et al. 2006). Family arrangements have implications for many dimensions of human and social life (Chibucos et al. 2004). In his work on the family, Vogel (2003, p. 393) states that “In the case of the family the principle is reciprocity and an informal contract between family members concerning responsibilities for the welfare of family members. There is a contract between spouses, between parents and their children, between adults and their elderly parents, and between adults and further relatives.”

Economists are interested in family arrangements because they are crucial to the study of economic well-being (Blundell et al. 1994; Rosenzweig and Stark 1997). From an economic perspective, the family allows for household members to specialize in the production of specific goods and services, as well as in doing specific household chores. Since 1776, with the publication of Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations, specialization has been recognized by economists as a way of increasing economic well-being because it allows people to allocate their effort to those activities where they are more productive and to take advantage of learning and repetition economies (Grossbard-Shechtman 2003). The family also allows for taking advantage of size economies; because there are economies from producing some services (e.g., cooking) to large groups rather than to single persons living alone (Rojas 2007a; Browning 1992). There are also substantial benefits from sharing the consumption of durable goods such as a house, a car, a stove, a blender, and so on.

From an economics perspective, the institution of the family involves an intra-household scheme of exchange and distribution. Due to its nature, the family requires for economic resources to be, up to a certain degree, pooled up together; hence, there must be a rule for distributing the economic benefits attained from these resources among family members. Different theories of the family have been advanced within the economics discipline to deal with this distributional issue.

In his pioneer work on the economic approach to the study of the family, Becker (1973, 1974, 1981) assumes that some family members—usually the head of the family or the main breadwinner—behave altruistically; while the other members of the family behave selfishly. Becker assumes that altruistic members are concerned about the well-being of the rest of the family; although, not necessarily as much as they are concerned about their own well-being. In consequence, the well-being of other members is incorporated in the utility function of altruistic members. Selfish members are just concerned with their own situation, and they have no interest in the well-being of the rest of the family. The altruistic behavior of income earners do imply that the economic well-being of any family member is not closely related to her breadwinning status. Therefore, in families where some members behave altruistically it is expected for breadwinners and senior family members to have lower economic well-being than other family members. On the other hand, in communitarian families it is expected for the economic benefits to be distributed in an equal way across family members, independently of their breadwinning and family status (Rojas 2006a).

A relatively recent literature approaches the family as a cooperative arrangement, where family members—in special, spouses and adult members—have selfish behavior; thus, they are only concerned about their own utility and they act unilaterally in order to maximize it. Thus, a marriage or a family is understood as a group of people who are willing to cooperate and share some resources because it is convenient to each one of them. Hence, the family emerges because it is of convenience to every household member, and this arrangement remains stable as long as all household members get greater benefits than in any alternative agreement. This approach has been called Cooperative Bargaining Models of Family, and it explains family decisions as a result of a collective-choice process; which takes place on the basis of selfish behaviors within the cooperative household equilibrium (Lundberg and Pollak 1993, 1996; Manser and Brown 1980; McElroy 1985, 1990; Pollak 1994, 2002).

According to Cooperative Bargaining Models of Family, the intra-household distribution of the gains from living in a family arrangement reflects the distribution of bargaining power that family members have (Binmore 1987). On the basis of their bargaining power, some members may have a smaller or larger access to the common pot (household income); hence, the economic well-being from a given household income is distributed in an unequal way across all household members. Lundberg et al. (1997) find out that those family members who have a larger personal income and, in consequence, make a larger monetary contribution to household income, do enjoy more decision-making power within the family.

This investigation tests whether an asymmetric distribution of the economic well-being benefits from household income does exist on the basis of a person’s breadwinning and family status.

This paper follows a subjective well-being approach to study economic well-being (Easterlin 1995, 2001; Clark and Oswald 1994; van Praag and Ferrer-i-Carbonell 2004; Rojas 2007b). The subjective well-being approach states that the best way to know people’s well-being is by directly asking them about their general life satisfaction (Veenhoven 1984). It is also common to ask people about their satisfaction with specific domains of life (Cummins 1996; Rojas 2006b).

The study of economic well-being and intra-household arrangements has been dominated by the use of so-called objective indicators (Bourguignon et al. 1994; Carlin 1991; Haddad et al. 1997; Lazear and Michael 1988; Thomas 1990, 1993, 1997). However, the use of so-called objective indicators is based on the uncorroborated presumption that the selected set of indicators is strongly related to people’s well-being as they experience it, as well as on the uncorroborated presumption of this relation being identical for all people.

Following the subjective well-being approach, this investigation constructs an economic-satisfaction indicator to proxy economic well-being. Hence, the investigation studies intra-household arrangements by analyzing how the relationship between economic satisfaction and household income is influenced by a person’s breadwinning and family status. If intra-household arrangements are basically communitarian then it is expected for a person’s economic satisfaction to depend on her household income but not on her breadwinning or family status. If there is altruism in the family then it is expected for those members with higher status to show a lower economic satisfaction, given household income. Family members with a higher status are expected to show a higher economic satisfaction in the case of a cooperative-bargaining arrangement.

3 The Database

3.1 The Survey

A survey was conducted in five states of central and south Mexico as well as in the Federal District (Mexico City) during October and November of 2001.Footnote 2 A stratified-random sample was balanced by household income, gender and urban–rural areas. Specific households in each area were randomly selected and an adult household member was directly interviewed in each household. 1540 questionnaires were properly completed; response rates were high for the subjective well-being questions (about 99%) and a little lower regarding socio-economic questions (about 93%). The sample size is acceptable for inference in central Mexico.

It is important to remark that only adult people were interviewed; thus, economic satisfaction refers to the economic satisfaction of an adult person (18 years old and more) that lives under a specific household arrangement and who has a family and breadwinning status in that family. Hence, the economic satisfaction of children and teenagers (less than 18 years old) in the family is not considered in this investigation. Furthermore, the unit of study is the person and not the family. It would have been preferable to interview all adult members in a household; however, financial constraints did not allow constructing such a database.

3.2 The Variables

The survey gathered information regarding the following quantitative and qualitative variables:

Demographic and social variables: education, age, gender, marital status, household composition (age and number of household-income dependent persons), family status (father, mother, daughter, son, grandfather, other), and breadwinning status (main breadwinner, secondary breadwinner, marginal breadwinner, no breadwinner).Footnote 3

Economic variables: current household income, personal expenditure, personal income.Footnote 4

Subjective economic well-being variables: four satisfaction questions related to the economic domain of life were asked: How satisfied are you with your income? (income); How satisfied are you with what you can purchase? (purchasing power); How satisfied are you with your housing conditions? (housing condition); and How satisfied are you with your household’s financial situation? (financial situation). Each satisfaction question had a seven-option verbal answering scale: extremely unsatisfied, very unsatisfied, unsatisfied, neither unsatisfied nor satisfied, satisfied, very satisfied, extremely satisfied. Satisfaction questions were handled as cardinal variables, with values between 1 and 7; where 1 was assigned to the lowest satisfaction level and 7 to the highest.Footnote 5

3.3 The Construction of a Subjective Economic Well-Being Indicator

Table 1 presents frequencies for the four subjective economic well-being variables (income, purchasing power, housing condition and financial situation). It is observed that there is a relatively high degree of dispersion in these economic-satisfaction variables.

It is desirable to have a single indicator for subjective economic well-being because of two main reasons: first, the four subjective economic well-being variables are highly correlated; second, a single variable simplifies the analysis. Hence, factor analysis was used to reduce the number of dimensions; the technique allows keeping as much information as possible, while it avoids the problem of duplicating its use. A principal-components technique was used to create the new economic satisfaction variable, and a regression method was used to calculate the factor score.

Table 2 shows the loads of each subjective economic well-being variable in the new economic satisfaction variable. It is clear that the new variable captures a great percentage of the information contained in the four subjective economic well-being variables, and that it is highly correlated with each one of them.

The new economic satisfaction variable was rescaled to a 0–100 basis to facilitate its manipulation and comparability. It has a mean value of 56.9 and a standard deviation of 16.6.

4 What Income Proxy to Use?

Any study of the relationship between economic satisfaction and income must take into consideration that income is a proxy of the capacity of a person to purchase goods and services that satisfy her economic needs and that there are many accounting and computational aspects in the construction of an income proxy. In other words, it is necessary to address the issue of what income proxy better reflects a person’s command over relevant resources. People live under different household arrangements; hence, an income proxy that can be compared across different household arrangements is required. The following income proxies can be considered: household income, personal expenditure, personal income, and family-size adjusted income measures.

Household income is limited because it does not take into consideration that families may be of different size, and that a person’s purchasing capacity and consumption of goods and services depends not only on her household income but also on the size of her family. Personal expenditure and personal income do not take into consideration that family members may get benefits from relevant economic resources even when they do not generate any personal income or do make no personal expenditure. Household per capita income and household equivalent income do adjust for the number—and sometimes the age structure—of family members. However, household per capita income is limited because it does not take into consideration that size economies may exist at the household level; it also presumes equal weights for all household members, independently of their age. Household equivalent income measures do assume arbitrarily defined weights and scale economies. Rojas (2007a) uses a subjective well-being approach to estimate the degree of scale economies at the household level in Mexico; he also estimates the economic burden of additional household members of different ages. Rojas (2007a) constructs a subjective well-being household equivalent income, which is shown to be superior to alternative income proxies in explaining a person’s economic satisfaction. This investigation uses Rojas’ subjective well-being household equivalent income as a proxy for household income which is comparable across families of different sizes and demographic composition.

Table 3 provides information about the cumulative distribution of observations at different income levels.

5 Family Status and Economic Satisfaction

Six categories for family status are distinguished: Father, mother, son, daughter, grandparent, and other. Table 4 shows the distribution of persons in the sample according to their family status.

It is observed in Table 4 that there are substantial differences in average economic satisfaction across family status. These differences in average economic satisfaction could emerge because of the status itself or because of other socio-demographic and economic characteristics which are correlated to a person’s family status.

The relationship between economic satisfaction and household equivalent income is a main concern of this investigation. If this relationship is independent of a person’s family status then there is no bias in using this person’s household equivalent income to assess her economic situation. However, if the relationship does depend on a person’s family status then household equivalent income must be adjusted by her family status in order to assess this person’s economic situation. Thus, the following regression is run to further explore the relevance of a person’s family status in the relationship between household equivalent income and her economic satisfaction. A father status is the category of reference.

where ES refers to economic satisfaction, in a 0–100 scale; ln Y refers to the logarithm of the subjective well-being household equivalent income; X control is a vector of the following control variables (ϕ is a vector of parameters); Education: level of education, in ordinal categories; Age: age in years; Marital status: vector of dichotomous variables, single is the category of reference. FS i refers to family status and is a vector of the following variables: FSmother is a dichotomous variable with value of one if the person has a mother status within the family, and a value of 0 otherwise; FSson is a dichotomous variable with value of one if the person has a son status within the family, and a value of 0 otherwise; FSdaughter is a dichotomous variable with value of one if the person has a daughter status within the family, and a value of 0 otherwise; FSgrandpa is a dichotomous variable with value of one if the person has a grandparent status within the family, and a value of 0 otherwise; FSother is a dichotomous variable with value of one if the person has other family status within the family, and a value of 0 otherwise.

Table 5 shows the results from the econometric exercise. It is observed that family status does make a difference in the relationship between household equivalent income and economic satisfaction. At low Y swb-eq (e.g., less than 1000 Mexican pesos per month) the economic satisfaction of sons and daughters is greater than that of other household members, in special than that of grandparents. The difference vanishes as Y swb-eq increases. This finding has important implications for the measurement of economic poverty: in low-income households it is not correct to assume that economic satisfaction is equally low for all household members. Because adult sons and daughters do have relatively high economic satisfaction levels in low-income households, then it could be possible for them to be non-economically poor persons in a presumed economically-poor household. For example, a son or a daughter that lives in a household with a Y swb-eq of 600 Mexican pesos per month does have the economic satisfaction of a father who lives in a household with a Y swb-eq of 1,100 Mexican pesos per month or a mother who lives in a household with a Y swb-eq of 1,000 Mexican pesos per month.

This finding indicates that at low-household income levels there is some degree of asymmetry in the intra-household distribution of resources that generate economic satisfaction. However, this asymmetry does not completely support the cooperative bargaining models literature, unless one is willing to assume that adult sons and daughters do have greater bargaining power than fathers and mothers. On the contrary, this finding could be associated to the practice of altruism by fathers and mothers at low-income levels. The situation of grandparents and other household members in low income households seems to be consistent with what cooperative bargaining models would predict. As household income rises, the privileges enjoyed by sons and daughters seem to vanish. The family moves towards a perfectly communitarian intra-household arrangement, with all household members having equal access to the benefits from the pool of the household’s economic resources.

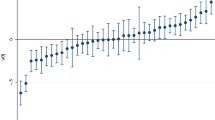

Figure 1 shows the relationship between economic satisfaction and Y swb-eq by family status for low household-income levels. All control variables in regression (1) are assumed to be equal to zero.Footnote 6

6 Breadwinning Status and Economic Satisfaction

The survey gathered information about a person’s self-reported breadwinning status. Four categories were used: main breadwinner, secondary breadwinner, marginal breadwinner, and no breadwinner. This variable provides information about a person’s status regarding her role in the generation of household income. Table 6 provides information about the breadwinning status distribution, as well as about average economic satisfaction by status.

It is observed in Table 6 that differences in average economic satisfaction across breadwinning status are relatively small. These differences could emerge because of the status itself or because of other socio-demographic and economic characteristics, which are correlated with a person’s breadwinning status.

As it was stated earlier, the relationship between economic satisfaction and household equivalent income is a main concern of this investigation. If this relationship is independent of a person’s breadwinning status then there is no bias in using this person’s household equivalent income to assess her economic situation. However, if the relationship does depend on a person’s breadwinning status then her household equivalent income must be adjusted by her breadwinning status in order to assess this person’s economic situation. Thus, the following regression is run to further explore the relevance of a person’s breadwinning status in the relationship between household equivalent income and her economic satisfaction.

where S B is a dichotomous variable, with a value of 1 if the person is a secondary breadwinner, and a value of 0 otherwise; M B is a dichotomous variable, with a value of 1 if the person is a marginal breadwinner, and a value of 0 otherwise; N B is a dichotomous variable, with a value of 1 if the person is no breadwinner, and a value of 0 otherwise.

All other variables have already been defined. The variable Gender, with a value of 1 for males and 0 for females, is added to the list of control variables.

The category of reference in regression (2) is a person who is main breadwinner. Thus, parameters β 1, β 2, and β 3 must be interpreted as the economic satisfaction difference that exists in a household with very low equivalent income (Y swb-eq = 1) between the secondary, marginal, and no breadwinner status and the main breadwinner, respectively. Parameter β 7 shows the relationship between the logarithm of household income and economic satisfaction for the main breadwinner; while parameters β 4, β 5, and β 6 indicate whether there is a difference in that relationship between the main breadwinner and the secondary, marginal and no breadwinner persons, respectively.

Table 7 shows the results from the econometric exercise. It is observed in Table 7 that marginal breadwinners do show a different relationship between household equivalent income and economic satisfaction with respect to other breadwinning status. This implies that at low Y swb-eq (e.g., less than 1000 Mexican pesos per month) the economic satisfaction of marginal breadwinners is greater than that of other household members. This difference vanishes as Y swb-eq increases. As it happened with family status, this finding corroborates that it is not correct to assume that economic satisfaction is equally low for all household members in low income households. For example, a marginal breadwinner in a household with a Y swb-eq of 600 Mexican pesos per month does have the economic satisfaction of a main breadwinner who lives in a household with a Y swb-eq of 1,200.

This finding shows that main and secondary breadwinners behave altruistically in low-income families, a result that is not consistent with what cooperative bargaining family models would predict.

Figure 2 shows the relationship between economic satisfaction and Y swb-eq by breadwinning status for low household income levels. All control variables in regression (2) are assumed to be equal to zero.Footnote 7

7 Share in Household Income

Section 6 worked with a self-reported breadwinning status to explore whether there is a difference in the relationship between economic satisfaction and household equivalent income on the basis of a person’s breadwinning status within the family. The same issue can be addressed on the basis of a person’s share in her household income. Let’s define a person’s share as the ratio of her personal income over her household income:

Table 8 provides some basic statistics for S per/H. It is observed that the mean value for the share of a person’s income in her household income is 0.58. Twenty percent of people in the survey do have a share of 0, meaning that they make no direct contribution to their household’s income. On the other hand, 37% of people in the survey have a share of 1, which means that they earn the totality of their household’s income. Cooperative bargaining family models would state that a larger share is associated to greater bargaining power within the household and, in consequence, with a more favorable cooperative equilibrium. Thus, if breadwinning status matters, then a person’s economic satisfaction should rise as her share of personal income in household income increases.

The following regression is run to study whether a person’s economic satisfaction is related to her share in the generation of household income:

All variables in regression (4) have already been defined. Table 9 shows the estimated parameters from the econometric exercise. It is observed that a person’s economic satisfaction slightly increases as her share in the generation of household income increases; however, this increase is not statistically different from zero. Thus, from a statistical point of view, a person’s share in the generation of household income does not make a difference in her economic satisfaction.

8 Conclusions

This paper shows that the subjective well-being approach can be useful to address such a relevant issue as the nature of intra-household arrangements. An understanding of intra-household arrangements is of relevance for the assessment of each family member’s well-being on the basis of household-level variables.

There are different theories regarding intra-household arrangements. Cooperative-bargaining models of the family state that the intra-household distribution of economic well-being depends on the distribution of bargaining power; those members with greater bargaining power do get greater economic well-being. Communitarian models of the family state that the benefits from intra-household resources are distributed in such a way that all family members do end up having a similar economic well-being. Altruistic models emphasize that some family members are willing to sacrifice the economic well-being for the benefit of others; thus, the distribution of economic well-being within the family is not equally distributed, but it does not follow suit the distribution of bargaining power.

The study of intra-household arrangements is of particular relevance for the study of poverty and the design of social programs. If families do follow altruistic or cooperative-bargaining arrangements then household income measures are not good proxies for the economic well-being situation of each family member. It could happen that there are persons with very low economic well-being in families which are classified as non-poor on the basis of their household income; as well as persons enjoying high economic well-being in families which are classified as poor.

It is a matter of empirical research to know what intra-household arrangements prevail in different cultures and countries. This paper has studied the nature of intra-household arrangements in Mexico, with a particular interest for the situation in low-income families. The paper’s findings cannot be extrapolated to other regions of the world; however, the empirical methodology based on the use of the subjective well-being approach may be useful to address what intra-household arrangements to exist across cultures.

In the case of Mexico, this paper has shown that low-income families do show significant levels of altruism; and that Mexican families become communitarian when their income rises. There is no evidence for cooperative-bargaining models being dominant.

It was found that adult sons and daughters have greater economic satisfaction than other household members in low-income households. Fathers and mothers do show some degree of intra-household altruistic behavior to benefit the economic well-being of their sons and daughters. On the other hand, grandparents who live in the household tend to attain less economic satisfaction from a given household income than other family members in low-income households.

A similar result is found when a person’s breadwinning status is considered. Marginal breadwinners do have greater economic satisfaction than other household members in low-income households. In Mexico, main breadwinners do not use their greater bargaining power to attain greater economic satisfaction, as it would be predicted by cooperative-bargaining models of the family.

These findings have important implications for the understanding of economic behavior. Altruism within the family creates an incentive scheme that influences the economic decisions of all household members. For example, it would be expected for those family members who benefit from the altruistic behavior of their parents to have less interest in generating income by themselves; on the other hand, altruistic persons in the family have an incentive to generate more income. It is clear that economic decision of household members would be different under alternative intra-household arrangements.

In addition, these findings are also of relevance for the design of social programs which aim to enhance economic well-being. Conditional cash transfer programs have proliferated in recent years across Latin American countries; these programs make conditional cash transfers to specific families which are selected on the basis of their household income and related household proxies. This investigation shows that the use of household-income proxies to select those households which will benefit from social programs is appropriate only in the case where communitarian intra-household arrangements do prevail. However, this does not seem to be the case Mexican families with low household income. It is clear that the existence of altruism in low household income families also has implications for the classification of people as being in economic poverty and for the determination of poverty figures.

The family is a central institution in any society; however, its nature varies across cultures and this has crucial implications for the assessment of economic well-being. The subjective well-being approach has proven to be useful to study intra-household arrangements and to understand distributional issues within the family.

Notes

A completely individualistic household constitutes a conceivable extreme case. In this situation family members act as housemates, so that they do not pool up their economic resources and they do hold separate budget and consumption accounts.

The author expresses his gratitude to CONACYT, Mexico for a grant that supported this research.

There is some overlapping between the family and the breadwinning status. For example, most of people in the survey with a ‘child status’ are also marginal breadwinners; however, not all marginal breadwinners have a ‘child status’, since there are also many wives and grandparents who are also marginal breadwinners. This provides a reason for studying separately the family and the breadwinning status.

Income figures are measured in Mexican pesos. The exchange rate at the moment of the survey was of US$1 dollar = MN$9.30 Mexican pesos. One peso was added to each figure in order to avoid zero values, which would be problematic for logarithm calculations.

It is important to remark that these economic-satisfaction questions have a categorical answering scale which, in principle, should be treated as ordinal rather than cardinal. However, due to the nature of the constructed economic satisfaction variable, as it is explained in Sect. 3.3???, it is preferable to work with these variables as cardinal ones. In addition, findings by Ferrer-i-Carbonell and Frijters (2004) suggest that this issue is of little relevance for the main results; they state in their conclusion that “We found that assuming cardinality or ordinality of the answers to general satisfaction questions is relatively unimportant to results.”

This assumption affects the consumption satisfaction levels, but not the relationship between consumption satisfaction and household equivalent income by family status.

This assumption affects the consumption satisfaction levels, but not the relationship between consumption satisfaction and household equivalent income by family status.

References

Becker, G. S. (1973). A theory of marriage: Part I. The Journal of Political Economy, 81(4), 813–846. doi:10.1086/260084.

Becker, G. S. (1974). A theory of marriage: Part II. The Journal of Political Economy, 82(2), S11–S26. doi:10.1086/260287.

Becker, G. S. (1981). A treatise on the family. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Bengtson, V. L., Acock, A. C., Allen, K. R., Dilworth-Anderson, P., & Klein, D. M. (Eds.). (2006). Sourcebook of family theory and research. London: Sage Publications.

Bergstrom, T. (1997). A survey of theories of the family. In M. Rosenzweig & O. Stark (Eds.), Handbook of family and population economics. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Binmore, K. (1987). The economics of bargaining. Cambridge: Blackwell.

Blundell, R., Preston, I., & Walker, I. (Eds.). (1994). The measurement of household welfare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bourguignon, F., Browning, M., Chiappori, P. A., & Lechene, V. (1994). Intrahousehold allocation of consumption: Some evidence on Canadian data. The Journal of Political Economy, 1002(6), 1067–1096.

Browning, M. (1992). Children and household economic behavior. Journal of Economic Literature, 30, 1434–1475.

Carlin, P. (1991). Intra-family bargaining and time allocation. In T. P. Schultz (Ed.), Research in population economics (Vol. 7, pp. 215–243). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Chibucos, T., Leite, R. W., & Weis, D. L. (Eds.). (2004). Readings in family theory. London: Sage Publications.

Clark, A. E., & Oswald, A. J. (1994). Unhappiness and unemployment. The Economic Journal, 104, 648–659. doi:10.2307/2234639.

Cummins, R. A. (1996). The domains of life satisfaction: An attempt to order chaos. Social Indicators Research, 38, 303–332. doi:10.1007/BF00292050.

Easterlin, R. (1995). Will rising the incomes of all increase the happiness of all? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 27(1), 35–48. doi:10.1016/0167-2681(95)00003-B.

Easterlin, R. (2001). Subjective well-being and economic analysis: A brief introduction. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 45(3), 225–226. (2).

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A., & Frijters, P. (2004). How important is methodology for the estimates of determinants of happiness? The Economic Journal, 114, 641–659. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0297.2004.00235.x.

Grossbard-Shechtman, S. (Ed.). (2003). Marriage and the economy: Theory and evidence from advanced industrial societies. New York and Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Haddad, L., Hoddinott, J., & Alderman, H. (Eds.). (1997). Intrahousehold resource allocation in developing countries: Models, methods and policy. Baltimore: John Hopkins Press.

Hart, G. (1990). Imagined unities: Constructions of ‘the household’ in economic theory. In S. Ortiz (Ed.), Understanding economic theories. Landam: University Press of America.

Lazear, E. P., & Michael, R. T. (1988). Allocation of income within the household. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lundberg, S., & Pollak, R. (1993). Separate spheres bargaining and the marriage market. The Journal of Political Economy, 101(2), 988–1010. doi:10.1086/261912.

Lundberg, S., & Pollak, R. (1996). Bargaining and distribution in marriage. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 10(4), 139–158.

Lundberg, S., Pollak, R., & Wales, T. (1997). Do husbands and wives pool their resources? Evidence from the UK child benefit. The Journal of Human Resources, 32(3), 463–480. doi:10.2307/146179.

Manser, M., & Brown, M. (1980). Marriage and household decision-making: A bargaining analysis. International Economic Review, 21(1), 31–44. doi:10.2307/2526238.

McElroy, M. B. (1985). The joint determination of household membership and market work: The case of young men. Journal of Labor Economics, 3(3), 293–316. doi:10.1086/298057.

McElroy, M. B. (1990). The empirical content of nash-bargained household behavior. The Journal of Human Resources, 25(4), 559–583. doi:10.2307/145667.

Pollak, R. A. (1994). For better of worse: The roles of power in models of distribution within marriage. The American Economic Review, 84(2), 148–152.

Pollak, R. A. (2002). Gary Becker’s contributions to family and household economics. NBER working paper No. W9232.

Rojas, M. (2006a). Communitarian versus individualistic arrangements in the family: What and whose income matters for happiness? In R. J. Estes (Ed.), Advancing quality of life in a turbulent world (pp. 153–167). Dordrecht: Springer.

Rojas, M. (2006b). Life satisfaction and satisfaction in domains of life: Is it a simple relationship? Journal of Happiness Studies, 7(4), 467–497. doi:10.1007/s10902-006-9009-2.

Rojas, M. (2007a). A subjective well-being equivalence scale for mexico: Estimation and poverty and income-distribution implications. Oxford Development Studies, 35(3), 273–293. doi:10.1080/13600810701514845.

Rojas, M. (2007b). The complexity of well-being: A life-satisfaction conception and a domains-of-life approach. In I. Gough & A. McGregor (Eds.), Well-being in developing countries: From theory to research (pp. 259–280). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rosenzweig, M., & Stark, O. (Eds.). (1997). Handbook of population and family economics. North Holland: Elsevier.

Smith, S., Hamon, R., Ingoldsby, B., & Miller, J. E. (2008). Exploring family theories. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Thomas, D. (1990). Intra-household resource allocation: An inferential approach. The Journal of Human Resources, 25(4), 635–664. doi:10.2307/145670.

Thomas, D. (1993). The distribution of income and expenditure within the household. Annales d’Economie et de Statistique, 29, 109–136.

Thomas, D. (1997). Incomes, expenditures, and health outcomes: Evidence on intrahousehold resource allocation. In L. Haddad, J. Hoddinott & H. Alderman (Eds.) Intra-household resource allocation in developing countries: Models, methods, and policy. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

van Praag, B. M. S., & Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A. (2004). Happiness quantified: A satisfaction calculus approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Veenhoven, R. (1984). Conditions of happiness. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Vogel, J. (2003). The family. Social Indicators Research, 64, 393–435. doi:10.1023/A:1025975129938.

White, J. M., & Klein, D. M. (2007). Family theories. London: Sage Publications.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rojas, M. Intra-Household Arrangements and Economic Satisfaction. J Happiness Stud 11, 225–241 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-009-9134-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-009-9134-9