Abstract

Aspirations, along with attainments, play an important role in shaping well-being. Early in adult life women are more likely than men to fulfill their material goods and family life aspirations; their satisfaction in these domains is correspondingly higher; and so too is their overall happiness. Material goods aspirations refer here to desires for a number of big-ticket consumer goods, such as a home, car, travel abroad and vacation home. In later life these gender differences turn around. Men come closer than women to fulfilling their material goods and family life aspirations, are more satisfied with their financial situation and family life, and are the happier of the two genders. An important factor underlying the turnaround in fulfillment of aspirations for material goods and family life is probably the shift over the course of the life cycle in the relative proportion of women and men in marital and non-marital unions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Aims

Women start adult life happier than men, but end up less happy. This reversal is largely due to a similar turnaround in the relative satisfaction of women and men in each of two life domains—finances and family (Marcelli and Easterlin 2007). At the beginning of the adult life course women are more satisfied than men with both their financial situation and family life; at the end, they are less satisfied.

As originally construed by Campbell (1981) satisfaction in a given domain depends on the net balance between aspirations and attainments. Empirical tests of this hypothesis have been limited, however, because of a lack of data on aspirations. Indeed, in life course studies there are, to our knowledge, no empirical studies linking domain satisfaction to the net balance of aspirations and attainments. In this paper we demonstrate that the life course differentials observed in one data set between women and men in satisfaction with both family life and finances are consistent with the life course differentials observed in a second data set in the net balance of aspirations and attainments. The aim of this paper is to provide new empirical support for the aspirations/attainments model of domain satisfaction. In addition, we offer speculative evidence on what may be principally behind the changing balance of aspirations and attainments in family life.

2 Conceptual Framework

The notion that well-being in a particular realm of life depends on the balance between one’s aspirations and attainments is found in disciplines ranging from economics (de la Croix 1998; March and Simon 1958; Siegel 1964), to psychology (Lewin et al. 1944; Solberg et al. 2002), to contemporary quality-of-life studies (Michalos 1985 provides a good overview; cf. also Michalos 1991). In the domain of family life, for example, one’s aspirations, simply put, might be for a happy marriage with two children. Satisfaction with family life would reflect the extent to which one’s attainments match these aspirations—the greater the shortfall the less the satisfaction with family life. Over the life course aspirations, attainments or both may change and alter judgments on satisfaction. Given attainments, aspirations might increase, consequently lowering satisfaction, or decrease, raising satisfaction. Given aspirations, attainments might move closer to one’s goals, raising satisfaction, or farther away, lowering satisfaction. Aspirations and attainments may also be interdependent to some extent.

One’s overall well-being is the net outcome of satisfaction with each of the various domains of life—material living conditions, family life, and so on. The life domain approach to explaining personal well-being was pioneered several decades ago by psychologist Angus Campbell and his collaborators (Campbell 1981; Campbell et al. 1976). An advantage of this approach is that it classifies into a tractable set of domains the everyday circumstances to which people refer when asked about the factors affecting their personal happiness or general satisfaction with life. Although there is not complete agreement on what domains of life are conceptually preferable, virtually all studies agree that family life and finances are among the most important in determining happiness (Cummins 1996; Rojas 2007; Salvatore and Muñoz Sastre 2001; Saris et al. 1995; Van Praag and Ferrer-I-Carbonell 2004; Van Praag et al. 2003). In what follows we first examine gender differences in life course aspirations and attainments in each of these two domains, compare the net balance of aspirations and attainments to life course differences in satisfaction with that domain, and then link the two domain patterns to life cycle differences in happiness. We also explore in a preliminary way one factor that may help explain gender differences in the balance between aspirations and attainments over the life course. Our data on aspirations and attainments do not exhaust the range of concerns affecting satisfaction in each domain, but we believe they touch on key elements of these concerns, and constitute a step forward in linking the empirical study of aspirations to the analysis of subjective well-being.

3 Data

In the best of all possible worlds, one would have nationally representative annual surveys that included questions on domain satisfaction as well as aspirations and attainments. For lack of such data, we analyze here two different data sets—one containing information on aspirations and attainments; the other, on domain satisfaction and happiness.

Data on aspirations and attainments are from nine nationally representative surveys conducted by the Roper-Starch Organization about every three years from 1978 to 2003 that include questions on the “good life” (Roper Reports from 1997 to 2003 were generously made available by NopWorld, www.nopworld.com; earlier reports, by the Roper Center for Public Opinion Research at the University of Connecticut.). In these surveys the questioning procedure is as follows (see Appendix A for the full survey question):

-

1.

We often hear people talk about what they want out of life. Here are a number of different things. [The respondent is handed a card with a list of about 25 items] When you think of the good life—the life you’d like to have, which of the things on this list, if any, are part of that good life as far as you personally are concerned?

-

2.

Now would you go down that list and call off all the things you now have?

The answers to question 1 tell us about an individual’s aspirations; those to question 2, their attainments. The excess of aspirations over attainments—which we define here as the “shortfall”—is the extent to which aspirations are unfulfilled.

In response to open-ended questions on the sources of personal well-being the things typically cited by people are matters of everyday life, those that consume most people’s time and energy, and over which they feel they have some control (Easterlin 2001). The good life questions are not open-ended, but the list of items presented to respondents overlaps substantially the kind of things most frequently mentioned—especially matters relating to material goods and family life. In regard to family life the Roper item that we principally use here is that asking about a “happy marriage”—whether the respondent considers it part of the “good life” and whether the respondent has a happy marriage. In the family domain we also touch briefly on desires for children. In the material goods domain, our analysis is based on responses regarding each of ten “big-ticket” consumer goods—ranging from a home of your own, TV, and car, to “nice clothes”, travel abroad, a swimming pool, and vacation home. We construct for each respondent a measure of the total number of these ten goods that the respondent considers part of the good life, and, among those considered part of the good life, how many the respondent actually has.

As mentioned, to gauge how respondents differ in regard to the fulfillment of their aspirations, we compute their “shortfall”, the excess of aspirations over attainments. At the individual level, the shortfall with regard to a “happy marriage” is either zero or one—a person either does or does not have a happy marriage. In the goods domain, the shortfall at the individual level could in principal range from zero (the respondent has every one of the big-ticket consumer goods named as part of the good life) up to ten (the respondent considers every big-ticket consumer good part of the good life but has none of them). In the analysis that follows we present the mean for all respondents of a given gender. For example, if at a given age six-tenths of women who consider a happy marriage part of the good life actually have a happy marriage (so that the shortfall value for each is zero) while four-tenths who desire a happy marriage do not have one (so that each has a shortfall value of one) then the proportion of women with a shortfall is 0.4. Because individual shortfall responses can range from zero to ten in the goods domain, the mean shortfall value for respondents is the average number of big-ticket consumer goods that respondents want but do not have.

In the Roper data age is reported mainly in five-year age groups, and we assign age to individual respondents based on the midpoint age of the group in which they fall, e.g. an individual in the 45–49 age group is assigned a value of 47. The exception is the oldest age group. This is usually 65+, for which we assign age 73; for recent surveys it is 70+, and we assign age 78. Because of the lumping together of the older age population, the life cycle patterns of these later ages are not well-defined, but because this problem applies equally to both females and males, we believe the gender difference at later ages is roughly representative.

The satisfaction and happiness data are from the United States General Social Survey (GSS) conducted by the National Opinion Research Center (Davis et al. 2005). The GSS is a nationally representative survey conducted annually from 1972 to 1993 (with a few exceptions) and biannually from 1994 on. The GSS is a survey of households, and weighted responses are used here to represent more accurately the population of persons (Davis et al. 2005).

For happiness there are three response options in the GSS; for financial satisfaction, also three options; for family satisfaction, seven options. The specific question for each variable is given in Appendix B. The analysis here is based on the surveys from 1973 to 1994, the period in which questions on all three items used here were included. The present analysis follows the procedure common in the literature in that the response of an individual to each question is assigned an integer value, with a range from least satisfied (or happy) equal to 1, up to the total number of response options, e.g., three for happiness, seven for family life satisfaction (cf. Blanchflower and Oswald 2004; Frey and Stutzer 2002; Veenhoven 1993). Descriptive statistics for these variables and the Roper variables on aspirations and attainments are given in Appendix C. Both data sets are representative of the non-institutionalized US adult population.

4 Methods

In both data sets the average life cycle pattern of a variable—aspirations, attainments, satisfaction, and happiness—is estimated for each gender by regressing that variable on age, controlling for year of birth (birth cohort), race, education, and time (in dummy form). The life cycle pattern of the variable is the estimated value at each age when mean values for all independent variables other than age are entered in this regression equation. The value of the variable, so estimated, differs from the raw mean of the variable at each age in that it controls for differences by age in the composition of persons by essentially fixed characteristics—birth cohort, race, and education—as well as period effects. The regression technique used throughout is logit or ordered logit, because responses to the several variables are categorical and are either binary or number three or more. Ordinary least squares regressions yield virtually identical results, suggesting that the findings are robust with regard to methodology.

It is worth emphasizing that in any analysis that seeks to generalize about life course patterns, it is essential to control for birth cohort. Inferences about life course change are often made from associations with age observed at a single point of time. In terms of the present analysis, one might find, for example, that in 1990 material goods aspirations of those age 65 are less than those at age 25, and conclude from this that material goods aspirations decline with age. But those age 65 in 1990 were born in 1925 and raised in the economically depressed period from 1930 to 1945, while those age 25 in 1990 were born in 1965 and raised in a much more affluent period. Hence, the 1990 difference in material goods aspirations between 65 and 25 year-olds might be due to a difference in material aspirations arising from their different life histories, rather than a difference in age.

Clearly, to derive life course generalizations what one wants to do is to follow persons from a given birth cohort as they age over time. To follow a cohort over the entire adult life cycle, however, would require data spanning a period of upwards of 70 years and such data are not available. But the two data sets here span 20–25 years, and permit one to follow a birth cohort over a considerable segment of the life cycle. In both data sets some persons are already middle or older age when the survey begins, so the control for birth cohort means, in effect, that segments of life cycle experience for numerous overlapping birth cohorts are combined to infer the typical life cycle pattern. Controls for race and education are also needed, because older age groups and older cohorts differ somewhat in their demographic composition from younger, having somewhat larger proportions of nonblack and less educated persons.

Each data set provides a random sample from one survey year to the next of persons from the same birth cohort, but not the responses of exactly the same members of the cohort; thus it is a “synthetic” panel. One of the benefits of a synthetic panel is that the data are a random sample of the entire population, thus avoiding the problem of possible bias due to sample selectivity and attrition. But because a synthetic panel does not follow exactly the same individuals as they age, it is not possible to study variability in individual life course patterns, and the analysis is necessarily confined to the average pattern.

The sample characteristics of each gender by age, race, education, and marital status are, in general, quite similar in the Roper and GSS surveys included here (Table 1). The characteristic in which the two data sets differ most is birth cohort, with the Roper survey including a somewhat larger proportion of recent cohorts and fewer early cohorts. This difference is because the Roper surveys start and end several years later than the GSS surveys. We could reduce the birth cohort disparity by eliminating the three Roper surveys taken after 1994, but to do so would reduce the Roper sample size by one-third. It would also shorten the maximum life cycle segment observed for a birth cohort from 25 to 16 years, thus weakening our ability to trace the life cycle pattern of each cohort. We decided, therefore, to retain the complete Roper data set, in effect assuming that life cycle patterns are the same across all cohorts.

5 Results

5.1 Gender Differences in Aspirations, Attainments, Satisfaction, and Happiness

5.1.1 Family Life

Throughout most of the life cycle the desire for a happy marriage is high among both women and men (Fig. 1a; the regressions on which the figure is based are given in Table 2, columns 1 and 2). At the start women’s aspirations are slightly higher than those of men. Then, for both genders aspirations decline gradually with age but somewhat more rapidly for women. Beyond age 42 the proportion of women desiring a happy marriage is less than that of men and the gap continues to widen slightly into older age.

Happy marriage: aspirations, attainments, and shortfall, by gender and age. Source: Table 2; Data: Roper

This gender difference in the pattern of life cycle marriage aspirations would in itself make for less satisfaction among women than men at younger ages and more at older ages. But in young adulthood women are more likely than men actually to have a happy marriage, while late in life the opposite is true (Fig. 1b; Table 2, columns 3 and 4). Moreover, the gender gap with regard to having a happy marriage is greater than that with regard to desires at both the youngest and oldest ages. Consequently, for women the shortfall—or failure to attain aspirations—is less early in the life cycle, and greater later on (Fig. 1c).

Thus, as far as a happy marriage is concerned, the early life advantage and late life disadvantage of women implies that at the start of the life cycle women would be more satisfied with family life than men, and at the end less satisfied. Turning to the GSS data set, we find that this, in fact, is the case (Fig. 2; Table 3, columns 1 and 2). The gender cross-over in fulfilling desires for a happy marriage occurs earlier, however, (at age 39) than that in satisfaction with family life (age 64). But family life consists of more than a happy marriage, and it is especially likely that children help sustain beyond age 39 the family life satisfaction of women relative to men. In our data women and men are virtually the same throughout the life cycle in terms of fulfilling their desires for number of children. However, family life is a more important ingredient of happiness for women (Marcelli and Easterlin 2007, Table 1). Thus, it is likely that children help sustain the family life satisfaction of women relative to men beyond the age when women’s attainment of a happy marriage starts to fall short of that of men.

Satisfaction with family life by gender and age. Source: Table 3, columns 1 and 2; Data: GSS

5.1.2 Big-Ticket Consumer Goods

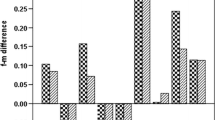

In the material goods domain a turnaround in the attainment of aspirations occurs similar to that in family life. At young adult ages the shortfall in attainment of material goods aspirations is greater for men than for women; in later life the shortfall is greater for women (Fig. 3c). The greater shortfall for men at younger ages is chiefly due to men having greater material goods aspirations (Fig. 3a). The greater shortfall for women in later life is largely because they actually have somewhat fewer big-ticket consumer goods than men (Fig. 3b). Table 4 presents the regression results on which Fig. 3 is based.

Big-ticket consumer goods: aspirations, attainments, and shortfall, by gender and age. Source: Table 4; Data: Roper

The shortfall reversal in Fig. 3c is for all ten big-ticket consumer goods taken together, but each of the individual material goods shows a similar reversal except for one. The exception is the fulfillment of aspirations for “nice clothes”, for which women’s shortfall is always greater than men’s and increases over the life course.

The gender difference in satisfaction with finances conforms quite closely to what one would expect based on that in the attainment of aspirations for big-ticket consumer goods (Figs. 3c and 4). Early in adult life men have a greater shortfall than women in fulfilling their material goods aspirations and are correspondingly less satisfied with their finances; later in life, women have a greater shortfall and are the less satisfied gender. The cross-over age for the shortfall in attainment of big-ticket goods aspirations (45) is quite close to that in satisfaction with finances (41).

Satisfaction with finances by gender and age. Source: Table 3, columns 3 and 4; Data: GSS

5.1.3 Happiness

Personal happiness depends in large part on how well one is doing with regard to family life and finances. Differences between women and men in the life cycle pattern of overall happiness are very largely what one would expect based on the domain satisfaction patterns. Early in adult life women are more satisfied than men with their family life and finances and correspondingly happier (Figs. 2, 4, and 5; Table 3). In late life men feel better about their family and financial circumstances and are the happier of the two. The cross-over in satisfaction with family life occurs at age 64 and that in financial satisfaction at age 41. As one might expect, the cross-over in happiness falls between the two, at age 48. As has been seen, these gender differences in domain satisfaction very largely reflect life cycle differences between women and men in fulfillment of their family and material goods desires. Thus, when the life course gender differentials in the two data sets are compared, we find patterns consistent with the theory that reversals in the net balance of aspirations and attainments cause corresponding gender shifts in domain satisfaction, and the shifts in domain satisfaction, in turn, lead to a reversal in the relative happiness of women and men.

Happiness by gender and age. Source: Table 3, columns 5 and 6; Data: GSS

5.2 Differences by Race, Education, and Birth Cohort

Happiness differences by race, education and birth cohort are also largely consistent with differences in the fulfillment of aspirations. Although these differences are not the primary concern of this paper the regression results reported here provide new evidence on aspirations and attainment differentials for each of these characteristics. It is useful to note them briefly therefore, because they provide additional support for the relevance of the aspirations/attainments model to explaining well-being.

5.2.1 Race

Blacks have lower marriage aspirations than whites, are less likely to have a happy marriage, and—despite their lower marriage aspirations, are less likely to achieve a happy marriage (Table 2). With regard to big-ticket consumer items, blacks tend to want more than whites (although for women the difference is not statistically significant), have considerably less, and, in consequence, fall much shorter than whites in fulfilling their desires for these big-ticket goods (Table 4). These greater shortfalls for blacks than whites in achieving their family life and material goods aspirations are consistent with numerous findings that blacks are less happy than whites (Blanchflower and Oswald 2004; Easterlin 2001; Frey and Stutzer 2002).

5.2.2 Education

Setting aside differences in gender, age, race and birth cohort, those with more education are happier than those with less (Easterlin and Sawangfa 2006). This happiness difference corresponds to what one would expect based on educational differences in success in fulfilling aspirations for material goods. Although better educated persons have slightly higher material goods aspirations than those less educated, the amount of goods they have is even greater, and the result is that they come closer to fulfilling their material goods aspirations (Table 4). In the family domain those with more education are more likely both to want and to have a happy marriage (Table 2). These family life differences in aspirations and attainments balance out so that there is no statistically significant difference by level of education in the shortfall in achieving a happy marriage. So far as the data go, therefore, they suggest that happiness differences in education are linked chiefly to the greater success of the more educated in achieving their material goods aspirations.

5.2.3 Birth Cohort

Cohort differences in the fulfillment of both family life and material goods aspirations are consistent with cohort differences in global happiness. At a given age recent cohorts are less likely than their predecessors to want a happy marriage, less likely to have one, and more likely to fall short of achieving their marriage aspirations (Table 2). Also, as one would expect, recent cohorts have more big-ticket items than earlier cohorts (Table 4). But their aspirations for such goods are even higher. As a result, success in attaining aspirations for these goods is less for recent cohorts than earlier. These greater shortfalls in the marriage and material goods domains for recent cohorts are consistent with their typically lower levels of happiness (Easterlin and Sawangfa 2006).

5.3 Sources of Gender Differences in the Fulfillment of Aspirations

Much of the social science literature focuses on the determinants of attainments. In the family domain, for example, there is a large theoretical and empirical literature on the factors underlying the formation of unions and the number of children that people have (for references, see Becker 1991; Easterlin 1987, 2004; Oppenheimer 1988). In the material goods domain, the determinants of income and consumption levels are widely studied. With regard to the determinants of aspirations, however, there is little more than conceptual recognition of the importance in the shaping of early adult-life aspirations of one’s childhood socialization experience, and the reshaping of aspirations during adulthood by on-going experience. We can see evidence here of this shaping and reshaping of aspirations in regard to desires for a happy marriage. In keeping with the social norms instilled in the course of their upbringing, about nine out of ten young people reach adulthood wanting a happy marriage (Fig. 1a). But over the life course the proportion who actually have a happy marriage barely ever exceeds six in ten (Fig. 1b). It is likely that the disappointment for those who fail to reach the goal of a happy marriage gradually erodes marriage aspirations and contributes to the observed life course decline in those aspirations. This decline in marriage aspirations is greater for women than men probably because in later life women are more likely to be in broken unions due to separation, divorce and widowhood.

A detailed analysis of the gender differences in the attainment of aspirations is beyond the scope of the present analysis. But it is appropriate to note one important factor that seems relevant to explaining why in early adulthood women come closer to fulfilling their family life and material goods aspirations, while in later life men come closer. This factor is the gender difference at each age in the proportion in marital and non-marital unions.

Women typically form unions at an earlier age than men, so at younger ages a larger proportion of women are in unions. In older age, however, the opposite is true—men are more likely to be in unions than women. Mortality is higher among men than women, and as a result women in older age are more likely to be widowed while those men who survive are still in unions (see Fields 2003 and earlier Current Population Reports in this series published by the U.S. Census Bureau). This life cycle reversal in the proportion in unions is illustrated for those in marital unions in Fig. 6, which is based on the regressions in Table 5. Up to about age 34, the proportion of women currently married is greater than that of men; thereafter, the proportion is greater for men, and the difference widens with age.

Proportion married by gender and age. Source: Table 5; Data: Roper

The life cycle reversal in the proportion of women and men in unions obviously has implications for the likelihood of being in a happy marriage, but it also has bearing on the fulfillment of material goods aspirations. The financial position of persons in unions is typically better than those dependent solely or largely on their own resources (Schmidt and Sevak 2006; Waite 1995; Waite and Gallagher 2000). Hence the fact that at younger ages women are more likely than men to be in unions would increase the probability of their fulfilling their material aspirations, while at older ages the greater likelihood of women being in broken unions would decrease their chance of realizing their material goods aspirations.

6 Summary

Early in adult life women are more likely than men to fulfill their material goods and family life aspirations; their satisfaction in these domains is correspondingly higher; and so too is their overall happiness. In later life these gender differences turn around. Men come closer than women to fulfilling their material goods and family life aspirations, are more satisfied with their financial situation and family life, and are the happier of the two. An important factor probably underlying the turnaround in fulfillment of aspirations for material goods and family life is the shift over the course of the life cycle in the proportion of women and men in unions. In early adult life women are more likely than men to be in unions, and this makes for greater fulfillment of both family life and material goods aspirations. In later life women are less likely to be in unions, and correspondingly have a greater shortfall in the fulfillment of aspirations.

These conclusions are based on comparing two nationally representative data sets—one providing information on gender differences in aspirations and attainments; the other, on gender differences in domain satisfaction and happiness. What is noteworthy is that the gender differentials and cross-overs in these two quite separate surveys provide mutually consistent support for the aspirations/attainments model of domain satisfaction and happiness.

7 Conclusion

Economists and psychologists have rather different views on the sources of well-being, and the present results bear on this difference. Many economists adopt the view that well-being depends solely on actual life circumstances, and can safely be inferred from observing these circumstances (see Lewin 1996 on the evolution of this paradigm). In the terminology used here, knowledge of attainments—what people have—is sufficient to infer well-being. In contrast, psychologists see the effect on personal well-being of objective conditions as mediated by psychological processes—that judgments of well-being involve an evaluation of objective circumstances relative to goals or aspirations (Campbell 1972; 1981 was an early exponent of this view). Their skepticism of the economists’ point of view is neatly encapsulated by Angus Campbell’s complaint over three decades ago: “I cannot feel satisfied that the correspondence between such objective measures as amount of money earned, number of rooms occupied, or type of job held, and the subjective satisfaction with these conditions of life, is close enough to warrant accepting the one as replacement for the other (1972, p. 442; cf. also Andrews and Withey 1976; Lyubomirsky 2001).

The results here suggest that economists are more nearly right in the family domain, but—ironically—less so in their area of primary interest, the material goods domain. In the family domain, differences between women and men over the life cycle in aspirations for marriage and children are fairly small, and gender differences in satisfaction with family life depend largely on differences in attainments. In regard to material goods, however, men have as much as or more than women throughout the life cycle, but early in life their financial satisfaction is less than that of women, a situation explicable in terms of their greater material aspirations at that stage of life. We find a similar story if we turn from gender to birth cohort differences. Recent birth cohorts have more goods than earlier cohorts, but they are less satisfied with their financial situation because of their even greater goods aspirations.

The research implications of this analysis are clear—the need for work on the nature and determinants of aspirations. The Roper surveys used here provide some guidance on the empirical study of aspirations. There is need, however, for new conceptual and measurement inquiries that will flesh out more comprehensively people’s aspirations, especially in the family life and material goods domains so central to determining subjective well-being, and for incorporating questions on these aspirations in surveys of domain satisfaction and subjective well-being.

References

Andrews, F. M., & Withey, S. B. (1976). Social indicators of well-being: Americans’ perceptions of life quality. New York: Plenum Press.

Becker, G. (1991). A treatise on the family. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. (2004). Well-being over time in Britain and the USA. Journal of Public Economics, 88, 1359–1386. doi:10.1016/S0047-2727(02)00168-8.

Campbell, A. (1972). Aspirations, satisfaction, and fulfillment. In A. Campbell & P. E. Converse (Eds.), The human meaning of social change (pp. 441–466). New York: Russell Sage.

Campbell, A. (1981). The sense of well-being in America. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., & Rodgers, W. L. (1976). The quality of American life. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Cummins, R. A. (1996). The domains of life satisfaction: An attempt to order chaos. Social Indicators Research, 38, 303–328. doi:10.1007/BF00292050.

Davis, J. A., Smith, T. W., & Marsden, P. V. (2005). General Social Survey, 1972–2004 [CUMULATIVE FILE] [Computer file]. 2nd ICPSR version. Publication from Chicago, IL: National Opinion Research Center [producer], 2005. Storrs, CT: Roper Center for Public Opinion Research, University of Connecticut/Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research/Berkeley, CA: Computer-assisted Survey Methods Program (http://sda.berkeley.edu), University of California [distributors].

de la Croix, D. (1998). Growth and the relativity of satisfaction. Mathematical Social Sciences, 100(36), 105–125. doi:10.1016/S0165-4896(98)00009-2.

Easterlin, R. A. (1987). Birth and fortune: The impact of numbers on personal welfare (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Easterlin, R. A. (2001). Life cycle welfare: Trends and differences. Journal of Happiness Studies, 2, 1–12. doi:10.1023/A:1011504817292.

Easterlin, R. A. (2004). The reluctant economist: Perspectives on economics, economic history, and demography. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Easterlin, R. A., & Sawangfa, O. (2006). Happiness and domain satisfaction: Theory and evidence. Paper presented at the Conference on New Directions in the Study of Happiness, University of Notre Dame.

Fields, J. (2003). America’s families and living arrangements: 2003. Current Population Reports. Series P-28, Special Censuses, P20-553. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2002). Happiness and economics. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Lewin, K., Dembo, T., Festinger, L., & Sears, P. S. (1944). Level of aspiration. In J. Mc. V. Hunt (Ed.), Personality and the behavior disorders. New York: Ronald Press.

Lewin, S. (1996). Economics and psychology: Lessons for our own day from the early twentieth century. Journal of Economic Literature, 34, 1293–1323.

Lyubomirsky, S. (2001). Why are some people happier than others? The role of cognitive and motivational processes on well-being. The American Psychologist, 56(3), 239–249. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.239.

Marcelli, E. A., & Easterlin, R. A. (2007). The X-relation: Life cycle happiness of American women and men. Unpublished manuscript

March, J. G., & Simon, H. A. (1958). Organizations. New York: Wiley.

Michalos, A. C. (1985). Multiple discrepancy theory (MDT). Social Indicators Research, 16, 347–413. doi:10.1007/BF00333288.

Michalos, A. C. (1991). Global report on student well-being. New York: Springer Verlag.

Oppenheimer, V. K. (1988). A theory of marriage timing. American Journal of Sociology, 94(3), 563–591. doi:10.1086/229030.

Rojas, M. (2007). The complexity of well-being: A life satisfaction conception and a domains-of-life approach. In I. Gough & J. A. McGregor (Eds.), Wellbeing in developing countries: Form theory to research (pp. 259–280). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Salvatore, N., & Muñoz Sastre, M. T. (2001). Appraisal of life: “Area” versus “Dimension” conceptualizations. Social Indicators Research, 53, 229–255. doi:10.1023/A:1007160616388.

Saris, W. E., Veenhoven, R., Scherpenzeel, A. C., & Bunting, B. (Eds.). (1995). A comparative study of satisfaction with life in Europe. Budapest: Eötvös University Press.

Schmidt, L., & Sevak, P. (2006). Gender, marriage, and asset accumulation in the United States. Feminist Economics, 12(1–2), 139–166. doi:10.1080/13545700500508445.

Siegel, S. (1964). Level of aspiration and decision making. In A. H. Brayfield & S. Messick (Eds.), Decision and choice: Contributions of Sidney Siegel. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Solberg, E. C., Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Lucas, R. E., & Oishi, S. (2002). Wanting, having, and satisfaction: Examining the role of desire discrepancies in satisfaction with income. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 725–734. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.83.3.725.

Van Praag, B. M. S., & Ferrer-I-Carbonell, A. (2004). Happiness quantified: A satisfaction calculus approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Van Praag, B. M. S., Frijters, P., & Ferrer-I-Carbonell, A. (2003). The anatomy of subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 51, 29–49. doi:10.1016/S0167-2681(02)00140-3.

Veenhoven, R. (1993). Happiness in nations. Rotterdam: Erasmus University.

Waite, L. J. (1995). Does marriage matter? Demography, 32(4), 483–507. doi:10.2307/2061670.

Waite, L. J., & Gallagher, M. (2000). The case for marriage: Why married people are happier, healthier, and better off financially. New York: Doubleday.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful for financial support to the University of Southern California.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A

1.1 Good Life Questions from Roper Surveys

-

1.

We often hear people talk about what they want out of life. Here are a number of different things. (HAND RESPONDENT CARD) When you think of the good life—the life you’d like to have, which of the things on this list, if any, are part of that good life as far as you personally are concerned?

-

2.

Now would you go down that list and call off all the things you now have? Just call off the letter of the items. (RECORD BELOW)

Appendix B

2.1 Questions and Response Categories for Happiness and Satisfaction Variables, General Social Survey

-

HAPPY: Taken all together, how would you say things are these days—would you say that you are very happy, pretty happy, or not too happy? (Coded 3, 2, 1, respectively).

-

SATFIN: We are interested in how people are getting along financially these days. So far as you and your family are concerned, would you say that you are pretty well satisfied with your present financial situation, more or less satisfied, or not satisfied at all? (Coded 3, 2, 1, respectively).

-

SATFAM: For each area of life I am going to name, tell me the number that shows how much satisfaction you get from that area.

2.2 Your family life

-

1.

A very great deal

-

2.

A great deal

-

3.

Quite a bit

-

4.

A fair amount

-

5.

Some

-

6.

A little

-

7.

None

(Reverse coded here)

Appendix C

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Plagnol, A.C., Easterlin, R.A. Aspirations, Attainments, and Satisfaction: Life Cycle Differences Between American Women and Men. J Happiness Stud 9, 601–619 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-008-9106-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-008-9106-5