Abstract

In many western cities, housing opportunities of young people are increasingly constrained due to housing market reforms and decreasing affordability as a result of processes of gentrification. Little is known about how young people deal with these constraints and how this differs across class and other boundaries. This paper addresses this question, by showing how young people make use of various forms of capital to gain access to specific sections of the housing market. Connecting concepts of Bourdieu and De Certeau to theories about housing pathways, this paper presents new ideas about how young people follow different pathways as they navigate the housing field. Next to a linear housing pathway, this paper presents two other housing pathway types: young households can either follow a chaotic pathway deliberately and relatively successfully or become trapped in a chaotic pathway. This paper shows the possession of various forms of capital, and their utilisation has a marked influence on the type of pathway young people follow.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In recent decades, housing accessibility for young people has decreased in many European countries (Bugeja-Bloch 2013). In the wake of the financial crisis, intergenerational inequalities emerge as large-scale access to homeownership has enabled older generations to build up housing equity, whereas stricter mortgage lending criteria make it increasingly difficult for younger households to access the owner-occupied market (Doling and Ronald 2010; McKee 2012). The effects across different national and urban contexts are variegated, but general trends are young people staying with their parents for a longer period of time (Clapham et al. 2012), a larger dependency on the private-rental sector, as well as them having to spend a larger share of their income on housing when they do live independently. Furthermore, the accessibility of housing markets for young people in economically successful cities is also increasingly constrained by the processes of gentrification. The upgrading of inner-city boroughs leads to decreasing affordability of housing in these boroughs (Van Gent 2013), and tenure conversions from social and affordable private rent to owner occupancy increasingly restrict access to affordable rental housing (Boterman and Van Gent 2014). In the early stages of gentrification, cheap and poor-quality housing at a central location was the ‘natural’ habitat for young households without many economic resources, but with cultural capital (Rose 1984; Clay 1979; Van Criekingen and Decroly 2003). The upgrading of inner-city residential milieus is thus particularly problematic for young people as they generally prefer a central location (McNamara and Connell 2007).

In increasingly deregulated housing markets in which homeownership is promoted and social rent is becoming ‘marginalised’, young people will have to navigate housing in alternative ways. As young people generally have little economic capital, they cannot afford expensive rental apartments. Also, they are not yet in a stage in their life course and working careers in which they are willing or able to enter into homeownership and its associated long-term financial commitments. Lacking economic resources young people are likely to pursue specific strategies drawing on other forms of capital than just money to access housing (Boterman et al. 2013). Here, differences in parental support (see also Sage et al. 2013), ethnic background, and level of education are among the factors that can influence the housing trajectories of young people. Also, local social networks and knowledge about the local housing market and neighbourhoods (see Brown and Moore 1970) can be of importance in gaining access to housing.

Using a pathway approach, Clapham et al. (2012) identified various housing pathways of young people. The framework of pathways proves to be particularly relevant to describe the variety of possible ways in which young people navigate the field of housing. Yet, little is known about how young people construe different types of pathways. Drawing on the concept of housing pathways (Clapham 2002, 2005), this paper will analyse how young peopleFootnote 1 deal with the opportunities and constraints of a gentrifying housing market context: the city of Amsterdam. By focusing on how the formation of housing pathways is influenced by various forms of capital—among which economic, social, cultural, and symbolic capital (Bourdieu 1986)—this paper aims to demonstrate how young people deal with constraints on the housing market. We do so by focusing on the following research question:

How do young people deal with constraints on the housing market, taking into account different forms of capital, and how does this influence the formation of different types of housing pathways?

In this paper, we challenge the often-presumed linearity in which life courses and housing careers coincide. We posit that nonlinear chaotic pathways, with frequent moves and insecure arrangements, are not only the result of constraints and unanticipated events in the life course. Instead, it needs to be taken into account that young people frequently opt for temporary and uncertain housing arrangements as this allows them—among other things—to live in desirable locations. Furthermore, the possession of other, non-economic capitals facilitates the formation of alternative housing pathways.

The case of Amsterdam is particularly relevant for this study due to the widespread gentrification of inner-city neighbourhoods (Van Gent 2013). Furthermore, a large social-rental sector continues to exist that is inaccessible to most young people due to long average waiting times. High levels of demand, on the other hand, make the commodified housing stock relatively expensive.

2 Theory

2.1 From housing careers to housing pathways

A dominant view in housing studies understands housing as a market of commodities, that is, in a state of (dis)equilibrium and in a continuous process of matching supply and demand (Clark and Dieleman 1996). Demand is often modelled as the interplay of ‘classical’ factors such as demographic and ethnic characteristics (idem). Events in the life course, such as family formation and leaving the parental home, are among the key moments in which housing demand changes and residential mobility occurs (Clark and Dieleman 1996; Mulder 2006; Mulder and Lauster 2010).

On the supply side, a range of economic constraints (Hamnett and Randolph 1988) and the tenure structure and quality of the housing stock (Priemus 1986) play an important role in shaping the housing decisions of individual households. A pied collection of scholars have criticised these approaches for several reasons: first, in many welfare states, a large segment of the housing stock is highly regulated and de-commodified (Harloe 1995), which renders free-market explanations of the allocation of housing, less useful. Models that look at housing demand and supply rather than actually determine who is able to access what type of housing tend to have difficulties accounting for alternative allocation mechanisms. Social-rental housing in the Dutch context, for example, is allocated on the basis of waiting timesFootnote 2 or on the basis of an urgency status, which the tenants of a social-rental dwelling receive when their house is to be demolished or renovated (Kleinhans 2003).

Social constructivist perspectives on housing reject rational action assumptions of neo-classical and positivist housing models (Clapham 2002; Jacobs et al. 2004). They argue that behaviour from part of individuals and households in neo-classical housing studies is over-rationalised and that too little attention is paid to the structures that govern choices. Housing choices are considered practices that are learned and embodied. They are thus strongly linked to inequalities in society. Resources are not just a constraint, but are part of one’s social position in terms of class, gender, age, and ethnicity. Various authors have studied how non-financial resources can help people provide access to housing. This includes social networks, knowledge of possibly suitable locations to move to—the ‘awareness space’—and other forms of available information (e.g. Brown and Moore 1970; Van Kempen and Özüekren 1998). Yet, few studies have adopted a longitudinal framework to explain housing access over a series of moves using both financial and non-financial resources.

One of the more convincing critiques that build on social constructivist theory is offered by the housing pathway approach, coined by Clapham (2002, 2005). Clapham (2002, p. 63) defines housing pathways as ‘patterns of interaction (practices) concerning house and home, over time and space’. In opposition to what he refers to as positivist housing studies, the pathway approach does not assume that ‘households have a universal set of preferences and act rationally in their attempts to meet them’ (2005: 29). Clapham proposes to integrate perspectives on housing careers (Dieleman 2001; Kendig 1984) with Giddens (1991) structuration theory. He argues that the term ‘housing pathway’ is preferable to that of ‘housing career’, as the latter term implies that every move is an upward one in housing and/or neighbourhood quality and assumes a linear and stable trajectory (Forrest and Kemeny 1984). By definition, housing pathways are composed of individual housing steps to which the households in question managed to gain access. Even though these housing pathways emerge from the interrelatedness between individual households, household life, and housing experience (ibid., p. 64), Clapham argues certain ideal typical housing pathways can be generalised from these individual housing practices.

2.2 Housing pathways, habitus, and field

This paper will further develop the concept of housing pathways of young people by complementing it with the sociology of De Certeau (1984) and Bourdieu (1986). We argue that the theoretical and conceptual tools of habitus and capital are useful for housing studies in general (Kemeny 1992) and specifically for explaining how young people follow specific housing pathways through various housing fields. We draw on the pervious work of Boterman (2012a) who found social, cultural, and symbolic capital to play a role in middle-class households’ ability to access housing in various sectors of the housing market (see Table 1). The extent to which individuals possess these forms of capital depends on their habitus (the whole of an individual’s embodied dispositions). Yet, the forms of capital differ in terms of usefulness between different housing sectors. The value of capital becomes only manifest in interaction with what Bourdieu calls a field. Economic capital for instance is more useful in the owner-occupied sector than in the social-rental sector, where very different rules apply.

As Holt (2008, p. 239) argues, the construction of the habitus ‘occurs within specific spatial moments’. Thus, in a sequence of moves, households are likely to draw on similar forms of capital for each move, especially when these capitals have previously proven successful in acquiring a home. Then, within a single housing pathway—even when it leads across different housing sectors—similar patterns between access to (certain types of) housing and the utilisation of different forms of capital are likely to be found. The extent to which individuals can use these capitals to their benefit in the construction of a successful housing pathway depends on the practices within specific housing fields. Referring to De Certeau, Boterman (2012a) distinguished between tactical—ad hoc—and strategic—planned—behaviour to explain housing access class differences on the housing market. More strategic behaviour is associated with more control over one’s housing situation and with longer-term planning of subsequent steps in a more linear housing pathway. Relatedly, it has also been established that low-income residents can act as creative agents to maximise their opportunities within the social-rental sector (Williams and Popay 1999; also see Kintrea and Clapham 1986). Moreover, living in affordable council housing can also be a deliberate (strategic) decision by professional middle-class households, in order to be able to pursue other life or career goals (Watt 2005). Such strategically planned behaviour (or the absence of it) might also, or especially, be of importance when looking at series of housing decisions rather than when looking at a single move in isolation.

2.3 Housing pathways of young people

The relationship between young people and housing is a specific one. Already in the 1980s, it has been established that young households often experience a transitional phase in their housing situation before marriage (Jones 1987). Furthermore, a prolonged transitional phase before adulthood in the life course, increasing labour market flexibility, and higher levels of educational attainment contribute to shifting housing pathways of young people (e.g. Van Criekingen and Decroly 2003; Berrington et al. 2009). In recent years, following the international financial crisis, housing accessibility for young people has decreased in many European countries (Bugeja-Bloch 2013). Intergenerational inequalities emerge as large-scale access to homeownership has enabled older generations to build up housing equity, whereas stricter mortgage lending criteria make it increasingly difficult for younger households to access the owner-occupied market (Doling and Ronald 2010; McKee 2012). In the United Kingdom, evidence exists of young people becoming ‘trapped’ in low quality, expensive, and temporary private-rental dwellings (Rugg 2010; McKee 2012).

In most countries, a specific student-housing market exists. Several studies from the United Kingdom show how students share common dispositions and point towards the existence of a student habitus (Chatterton 1999; Smith and Holt 2007), which helps to explain how students often share similar housing demands and experiences. Within large student complexes, students were found to acquire social capital and cultural capital—e.g. knowledge of the (student) housing market—which helped them in subsequent steps on the housing market. This creates a ‘student advantage’ that enhances their later housing opportunities (Rugg et al. 2004). This points towards the formation of specific pathways of young people on the basis of the possession and gradual acquisition of various forms of capital. Sage et al. (2013) also discern a variety of pathways or trajectories that are associated with resources and constraints. They stress the importance of parental capital as a safety net, which enables more selective and more linear types of pathways. In this context, Ford et al.(2002, p.2457) argue that ‘although housing pathways might be more complicated than once they were, such pathways still exist and the chances that a young person follows one pathway rather than another is still largely a function of structural factors’. They summarise three main factors that influence housing pathways: constraints, family support, and the degree of planning and control by the individuals. These factors were found to lead to the formation of five different housing pathways, ranging from a linear planned pathway to a chaotic pathway (Ford et al. 2002). These studies generally conceptualise the chaotic pathway as primarily being the result of a lack of resources these young people possess and are able to use in order to gain access to housing.

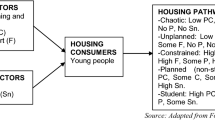

We argue that the formation of alternative, nonlinear pathways is not solely the result of constraints and a lack of any form of capital at young people’s disposal, but can also be the result of strategical and tactical navigating of housing fields. These practices relate to the forms of capital young households possess and to what extent they can use these forms of capital within different sectors of the housing market (see Table 1). The following section explains how the Dutch housing market is composed out of various housing sectors and subsectors that each have their specific allocation criteria.

3 The Amsterdam housing context

Despite clear trends of housing market deregulation, de-commodified social-rental housing still constitutes a large share of the housing stock (46 % in 2013) (Musterd 2014). Due to both new-build construction, with generally a larger share of owner-occupied dwellings, and tenure conversions of the existing rental stock (Boterman and Van Gent 2014), the owner-occupied sector grew from 16 % in 2002 to 28 % in 2013. The private-rental sector is relatively stable, although a small relative decrease can be discerned (from 29 to 26 %).

The social-rental sector with a rent cap of €681Footnote 3 is only accessible to households with a relatively low income (maximum household income of €34,229 in 2013), and housing is allocated on the basis of waiting time—the average waiting time for a social-rental dwelling is roughly 11 years in Amsterdam—or to those with an urgency status (see above). The private-rental sector in Amsterdam consists of two separate ‘subsectors’ namely the free-market and the (pseudo-market) affordable private-rental sector (Van der Veer and Schuiling 2005). These subsectors need to be considered separately, because they function on the basis of a different set of (allocation) rules. Within the free-market private-rental sector, no price regulation exists and this sector is—in principle—accessible to all types of households. Here, it is to be expected that housing is primarily distributed on the basis of economic capital. Rents in this sector are generally high (more than €1000/month is common), especially in the city’s central neighbourhoods, due to the small size of the stock and large demand for private-rental apartments.

On the other hand, the affordable private-rental sector (particuliere kernvoorraad) has rents below the rent cap, making economic capital of lesser importance. The affordable private-rental sector differs from the social-rental sector, since dwellings are not allocated on the basis of waiting times. Instead, landlords can decide how they allocate this affordable stock. Within this sector, various small private housing institutions exist. Even though these dwellings should in principle be accessible and affordable to most of the population, it was found that mainly young and highly educated native Dutch people rent within this sector (Dienst Wonen Amsterdam 2008). The steady growth of the owner-occupied sector initially offered young people the opportunity to access the owner-occupied market. Yet, due to a rapid increase in housing values before the global financial crisis and stricter mortgage lending criteria since the financial crisis, the owner-occupied sector has become more difficult to access and afford particularly for younger people (Boterman et al. 2013).

Next to these three official housing sectors (i.e. owner-occupied, private–rental, and social-rental), three other ‘subsectors’ need to be considered for this study. First, a large student-housing sector exists to which only students registered at a higher education institution based in Amsterdam can gain access. Contracts are temporary and officially end 6 months after the tenant cancels his/her registration as a student, for example when graduating. Student-housing is scattered across the city, although larger complexes exist at the urban periphery. In recent years, temporary student-container complexes were realised substantially boosting the availability of student-housing. Nevertheless, most students still live outside this sector. Second, a large (semi-)illegal and informal housing market exists, in which people illegally sublet their owner-occupied or (social) rental dwelling. Arguably, this illegal sector functions as an independent sector where official, institutional constraints are absent. Third, a temporary sector exists: short-term rent contracts are common for example when households (temporarily) move abroad or as part of anti-squatting regulations. The temporary sector frequently overlaps with the informal (semi-)illegal sector though.

4 Data and methods

This article draws on 44 semi-structured interviews with young people undertaken in 2012 and 2013. These interviews were part of a larger research project on the position of starter households, which included quantitative analyses and in-depth interviews with key stakeholders. The respondents were all aged between 20 and 35 years and acquired their first independent dwelling (i.e. not living in the parental home) in Amsterdam during the period 2001–2011. The interviews generally lasted 45–90 min and took the form of detailed housing biographies. Before, the interview respondents were asked to schematically draw their entire housing biography (the total of moves), which helped to overcome possible time distortions or biases on memory. Through these housing biographies, the respondents created temporally ordered narratives.

The respondents were asked to explain in detail how they acquired each dwelling, what alternatives they had, and the potential constraints they experienced. Furthermore, respondents were asked about their decision to move, as well as how they experienced each home and the neighbourhood. Respondents were also asked about their parental home and how they envisioned their housing situation in the (near) future. The extent to which respondents plan for the future is indicative of the strategic behaviour described above. All interviews were recorded and subsequently coded for these topics using Atlas.ti. Each residential move was coded as a unique case, which allows us to identify changes as well as constants over time. The names used in this article are fictitious, and quotes have been translated from Dutch into English.

The interviews were sampled to achieve variation in age, gender, education level, ethnic background, place of birth (specifically from within or outside the Amsterdam region), and occupation (e.g. working, student, or jobless) (see Table 2). Respondents were approached at locations where a wide spectrum of young independently living people with different backgrounds was likely to be found, e.g. IKEA and various town halls in the city. Some respondents were approached through limited snowball sampling to approach groups that would otherwise be difficult to reach. Lower-educated respondents are relatively underrepresented in the study, although their housing biographies give a good overview of (commonalities in) their housing pathways. Furthermore, it should be emphasised that roughly half of the Amsterdam working-age population is higher educated and that this share is higher among younger population groups (when graduated).

On the basis of the individual housing biographies, we define three housing pathways. The pathways are identified on the basis of (a) the housing market sectors and dwelling types they move through, (b) the reasons for moving, and (c) the type of moves and possible changing patterns over time. The first housing pathway, the linear pathway, consists of relatively few moves and relies on the formal housing market sectors (i.e. owner-occupied, social–rental, or private-rental). Respondents in this pathway generally move to adjust their housing situation to their preferences or life course.

In addition, we define two types of chaotic housing pathways: a progressive and a reproductive chaotic housing pathway. In both pathways, respondents move frequently, often between informal (semi-illegal), and often temporary housing arrangements. Yet, the two pathways differ between each other regarding the reasons for moving and changing patterns over time. The progressive chaotic pathway is characterised by greater control over one’s own pathway, while the reproductive chaotic pathway is characterised by frequently undesired forced moves. Furthermore, the progressive chaotic pathway shows gradual progress in the housing situation of the respondents and eventually moves to ever more secure housing arrangements. The next sections will further elaborate on these three general housing pathways.

5 The linear housing pathway

Linear housing pathways thus move through the official housing sectors only and are characterised by high levels of stability. A minority of the respondents of this research followed such a linear housing pathway. Yet, many respondents express the desire to follow a linear—or at least more secure—housing pathway. Various respondents state they are excluded from such a pathway though, primarily due to a lack of economic capital or waiting time. Due to housing prices and long waiting times, for the owner-occupied and social-rental sector, respectively, many young people depend on the private-rental sector. Here, however, additional income requirementsFootnote 4 prevent them from gaining access:

for a €1000 per month apartment you need an annual income of €50,000 […] We were willing to pay €1000 per month, it was within the range of what we could afford. But we could never meet these income requirements (Sara, 25, with her partner Jeroen).

Various respondents shared similar experiences of being excluded on the basis of income requirements, rather than their actual ability to afford the rent. Furthermore, letting agencies (including housing associations) generally pose additional requirements like a permanent (labour) contract and do not rent to groups of friends. Hence, predominantly dual-earner couples are able to rent in the private-rental sector.

This form of exclusion often occurs (soon) after students graduate, but before they have been able to accumulate sufficient economic capital. A gap exists between the student-housing sector and the subsequent housing options in all sectors of the housing market, which makes a linear progression of the housing pathway difficult for many recent graduates. As mentioned above, former students have to leave their student home shortly after graduation. Thus, this can be considered a key event in the life course where generally the (full time) entry onto the labour market is paired with a forced eviction from their student home and a lack of suitable housing options.

Respondents that successfully further their linear pathway cope with housing market constraints by strategically employing the economic capital and waiting time at their disposal to maximise their opportunities within the formal housing segments. By strategically planning their move and utilising additional forms of capital, these respondents manage to access, for example, the social-rental sector:

this place was not yet built, but rather a project about to be built. People [on the social-rental waiting list] look for something now, not in nine months, but I had the time: I could afford to wait nine months […] My conclusion was the competition would be smaller and this was also the case (Marco, 35).

Marco had relatively little waiting time (9 years, which is below average in Amsterdam) and knew he would soon start a new job with a higher income, which would disqualify him for a social-rental apartment. He strategically used time to his advantage, as he was able to wait a few months for the construction of the apartment block to be completed, while other households tend to apply for directly available apartments. His awareness of the existence of the project and the opportunity it gave him to gain access to the social-rental sector can be considered a form of cultural capital, since it expresses knowledge of the housing market.

Other respondents applied similar strategies. Former students frequently circumvent official rules and (illegally) stay in their student apartment after graduation to bridge the ‘post-graduation’ housing gap. This gives them more time to find a new dwelling, or to build up more economic capital or, in some cases, more waiting time. This enhances the likelihood of suitable housing becoming available:

Every time I applied I ended up around 100th (place on the waiting list) […] Then this whole block came [available] at once. I about was 97th on the waiting list at first and they also had 97 [apartments] or so. In the end I was on the reserve list, but enough people didn’t want it (Eefje, 22).

Eefje applied for a social-rental dwelling specifically designated to people aged below twenty-three. Here, waiting times are lower, but available options are scarce. By staying in her student apartment after graduation, she was able to wait long enough for this project to come on the market. Cultural capital is also applied to access the owner-occupied sector, to maximise the possibilities with the economic capital at disposal. This cultural capital is expressed through a thorough knowledge of the layout of Amsterdam, how to interpret the ‘value’ of a neighbourhood, and of the neighbourhoods that are gentrifying and, hence, make up for a relatively sound investment. Strategically employing capital forms at disposal can hence maximise outcomes:

we did research of course, we looked at KadasterFootnote 5 on who lives in the neighbourhood and what [housing] prices were common. We even looked up everyone who lived in the neighbourhood, so we knew more about them. […] Kadaster shows their names, through Linkedin and Facebook you can find everything. Just to see if they are educated people; what kind of people they are (Marco, 35 (second apartment)).

Another way respondents manage to follow a linear housing pathway is by postponing the moment of leaving the parental home. Here, family relations are key to explain how these respondents managed to secure a stable housing arrangements. Moreover, various respondents also strategically use their living arrangements with their parents to acquire an independent dwelling. One respondent, for example, managed to acquire an urgency status for the social-rental sector as his parental apartment was considered (too) small to live in with more than two adults. His knowledge of these ‘rules of the game’ can also be considered a form of additional cultural capital. Another strategy is to, formally or informally, split up the parental home into two independent apartments:

It was when I was eighteen or nineteen, our [social-rental] apartment had to be renovated anyway […] and we made use of the opportunity to turn it into two small apartments, because I only had a very small room. As I was getting older and it did not look like I was going to leave home, I wanted more privacy (Anouk, 24).

This strategy can enable young people to make a start with independent living, without having to deal with the constraints and high prices on the housing market. It must be emphasised that such benefits only come to young adults whose parents live in, or close to, Amsterdam. These family ties can thus also be seen as a form of capital that can be strategically employed, but which is not available to all young adults who (want to) make a start in Amsterdam.

It is shown that even in the case of a linear housing career the various steps on the housing market do not necessarily flow into one another. Instead, following severe housing market constraints, these young residents have to strategically use additional forms of capital to be able to follow a linear housing career.

6 Chaotic housing pathways

The interviews demonstrate that most respondents do not follow a linear housing pathway, but rather follow a chaotic housing pathway. Although the interviews give rich descriptions of a wide range of informal or unusual living arrangements and housing pathways, we define two general types of chaotic housing pathways—the progressive and the reproductive chaotic housing pathway. For both types of chaotic pathways particularly the informal (semi-illegal) sector, the temporary sector and the (free-market and affordable) private-rental sector play an important role. Yet, substantial differences exist, primarily regarding the search behaviour of respondents and, in relation to this, the outcomes of (series of) moves.

6.1 The progressive chaotic housing pathway

For respondents in the progressive chaotic pathway, a subtle interplay exists between, on the one hand, being forced to deal with constraints on the (official sectors of the) housing market and, on the other hand, deliberately choosing to divert from a linear pathway and, instead, opt for alternative housing options and arrangements. These respondents feel that following an alternative pathway enables them to live in desirable neighbourhoods, often for a below market-rate rent. Searching via the official routes is hence considered both difficult and unattractive. Generally low on economic capital, the informal (semi-)illegal and temporary housing sectors allow them to use other forms of capital:

I didn’t really have to make an effort, it was always quite easy. It is really a requirement in Amsterdam to know a lot of people. All the people I know that moved to a home have a large network […]. I considered registering [for social housing], but then they told me how long it would take before I could live in an acceptable neighbourhood. […] Using the official channels really has no use at all (Maarten, 28).

Maarten emphasises the importance of social capital and stresses how he could always find something via friends, family, or acquaintances. Furthermore, he describes official housing options as inaccessible and unattractive. Various respondents emphasise a similar confidence of always being able to find something. Following this sense of security, they are often willing to trade in an apartment with a stable contract for a temporary or illegal option, primarily to be able to live, albeit only temporarily, at a popular location. Asked the question why he traded a legally rented room for a temporary and illegally sublet room, one respondent answers:

Because up to now, a room always came to me really. I was bored of North, I wanted something more ‘Amsterdam’. This is a perfect location. From here I can search for something else in the centre (Roy, 24).

The spatial dimension plays a crucial role in the decision to opt for an insecure housing pathway. The examples above highlight the important role social capital plays in finding an affordable place in popular, often gentrifying, neighbourhoods. In contrast, economic capital is of little (initial) importance to find these homes and construe these pathways.

Thus, most respondents in this pathway consider their dependence on other forms of capital not only a constraint, but also a distinct advantage too. Therefore, they generally continue to use these other forms of capital to access formal housing market sectors when they want a stable housing situation in order to settle down. The example of Sara and Jeroen (see above) illustrates how other forms of capital, and search strategies, can be useful at a later stage in the life course (they were expecting a child) to acquire a stable housing arrangement:

[Jeroen’s parents] knew via via a real-estate agent who dealt in social-rental apartments and they were allowed to allocate a quarter of the apartments themselves. […] I called [a legal advisor] if this was legal and it was. He asked a commission fee though, which was not allowed. But yeah, we did it because otherwise we would not get in.

This commission fee—which was €12.000—was a necessity to acquire an affordable dwelling. Sara and Jeroen accepted such clandestine behaviour as a normal ‘part of the game’:

We agreed, so then I think it is a bit weak to say ‘I am going to ask it back anyway’, so I did not do this.

It is interesting to note that Sara and Jeroen in hindsight state how it would never have been possible to find a family apartment in an inner-city neighbourhood with a rent substantially below market rate through the official channels. Thus, social capital and a willingness to violate the law (a form of cultural capital) played a necessary role to access this affordable, private-rental apartment. Moreover, they chose this construction even though Jeroen’s parents were prepared to financially support them to buy a dwelling in one of Amsterdam’s cheaper, outer-ring neighbourhoods. Again, the spatial dimension of the progressive chaotic pathway plays an important role in this decision. Furthermore, this example shows that within the progressive chaotic pathway, clandestine behaviour is, to a certain extent, normalised, since it becomes a key form of capital for these respondents to improve upon their housing situation.

Alternative capitals are also used to strategically navigate the official housing market and circumvent institutional constraints. This gives respondents an advantage over other households. Various respondents, having ample experience with renting in the (semi-)illegal sector, use social and cultural capital to strategically negotiate the outcome of what formally is a random lottery. This is mainly relevant in the (free-market) private-rental sector, where apartments are generally allocated by lottery among those that meet the requirements. Chances to acquire an apartment are generally slim due to the large number of applicants. Various respondents report that they were able to negotiate with employees, for example of housing associations, to overcome the fact that they did not meet all requirements. Francisca, for example, stressed her upwardly mobile and high-educated status:

I told him [i.e. a housing association employee] I just started working, that I did not have a permanent contract, that I went to university and would live here with my partner who also studied. He liked this and he told me ‘write down on your application what you just told me’ […] they tell you it is a random system, but it is not random. Apparently they want dual-earner, high-educated people (Francisca, 28).

Alternative capital forms can also be used to substitute economic capital, to a certain extent, on the owner-occupied market, as the example of Maarten (see above) highlights:

My father owns a company specialised in housing foundations, so my next house is probably one with bad foundations because I can renovate it at a low cost. We know a lot of real-estate agents. I have just started to ask everywhere ‘do you know something? Keep me updated’ […] It is always beneficial when you can buy something underhand than via an agent. They always charge commission costs.

His specific cultural capital—knowledge of housing foundations—and ability to effectively employ ‘sweat equity’ allow Maarten to search in a niche market of the owner-occupied sector. Yet, again social capital is of importance to Maarten, although he now uses other persons in his network (e.g. real-estate agents) than when he looked for a room or small apartments, where he primarily sought among direct and indirect friends. It could be argued that his choice to rely on social capital was build up over time, due to previous experiences with finding an apartment and similar experiences within his social network.

Overall, in the progressive chaotic housing pathway, respondents frequently move—often to illegal or temporary apartments. Yet, even when making the step to a stable housing situation, they continue to use other forms of capital (social and cultural), often in addition to economic capital (which gradually becomes more important). Moving into insecure housing arrangements is often not tactical reactions to housing market constraints, but rather strategic trade-offs between stability and (inner-city) location (symbolic capital). This links to theories of gentrification as their choice for insecure inner-city apartments functions as a mark of distinction. Finally, without wanting to make any quantitative claims, respondents from Amsterdam or the Amsterdam region are overrepresented in the progressive chaotic housing pathway. These respondents generally have a local network through which the availability of housing is communicated (social capital) and more knowledge of Amsterdam’s housing market and neighbourhoods (cultural capital).

6.1.1 The reproductive chaotic housing pathway

Respondents in the reproductive chaotic pathway face similar constraints as respondents in the progressive chaotic pathway, but are less successful in dealing with them. Frequently, these respondents have to, unexpectedly, leave their apartment or room for a variety of reasons such as the ending of a relationship or an eviction by the landlord:

In the end I was more or less evicted […] because it was illegal subletting, she [i.e. the subletter] was very scared. I was not allowed to make noise and people were hardly ever allowed to visit me. […] The first thing I found was a room in Amstelveen […] Those were just two guys wanting to make some easy money. […] I had to accept it because I had to leave the [other] dwelling. Back to my parents was no option since I wanted to stay in Amsterdam (Myrthe, 24).

This quote is exemplary for most respondents in the reproductive chaotic pathway, where the sudden urgency to find a new place to live often leaves respondents with little alternatives but to move to low quality and often expensive housing, again predominantly within the illegal circuit. Hence, they reproduce their precarious situation in this sector. This leads to the formation of a housing pathway that consists of various undesired moves born out of the necessity to leave the former place. Yet, the possession of alternative capital forms can mediate the outcomes in the reproductive chaotic pathway as well as the example of Laurens illustrates. He lived together with someone else, but due to constant annoyances.

the situation became untenable and then I went back [to my parents]. I immediately started looking and registered for student housing. I wasn’t registered long enough and didn’t get anything.

They [i.e. the parents of his partner] placed me on top of the waiting list. […] These people just thought ‘this guy needs a new place to live’ and then this house came available. I didn’t have to do anything actually (Laurens, 23).

Laurens was able to use his parental home in Amsterdam as a safety net, which gave him more time to find a good place to live. Furthermore, his large social network (social capital) subsequently helped him to find a new place to live. However, it is important to note that both cases illustrate how respondents in the reproductive chaotic pathway tactically react upon an unexpected situation. This contrasts the situation in the progressive chaotic pathway, where respondents more strategically orchestrate their moves, albeit often within temporary and informal, (semi-)illegal sectors.

Thus, respondents in the reproductive chaotic pathway experience both substantial constraints on the official segments of the housing market and have difficulties finding suitable accommodation via alternative channels. As a result, they have a feeling of being stuck as the following (rather extreme) example shows:

I definitely did not [want to live] with other people. […] It is the same as here, but worse. People you do not know, people you may not like…

[If I leave] I have to go another dwelling, probably smaller, definitely only for one person. Smaller and more rent, so I thought: ‘I will stay here and will see what happens’. At a certain point they [i.e. the housing association] said: ‘you can stay, but you risk being evicted with a three months notice’ (Ahmed, 27).

Ahmed lived in his parental home in an apartment listed for renovation. While his mother made use of the urgency status to move elsewhere, Ahmed decided to stay in his old parental home despite having an (individual) urgency status, because he fears moving would result in having to pay more rent. Furthermore, he does not consider the alternative housing arrangements common in the informal housing sectors.

Reproductive chaotic pathways thus tend to persist for a longer period of time, moving through various precarious living arrangements. As the following example shows, it can force respondents in this pathway to flexibly interpret their household arrangement. Dorien and Stefan, a working couple, moved through various (semi-)illegally rented apartments and were confronted with eviction. This led the couple to accept a room in a shared apartment:

We needed something and could get this. Fine, then we move there I lived there with my boyfriend together with other people. I did know them, but it was an awkward situation. After half a year of living as a couple with a lot of housemates, two or three others, we decided it did not work at all (Dorien, 26).

Dorien indicates she used all channels to find an independent apartment and ultimately got one through an indirect contact:

The lady who owns this home wanted to rent it out, because she lives elsewhere with her partner. But she wanted to remain registered at this address, because otherwise you have to officially rent it outFootnote 6 […]. So my partner is registered here, but I am not. This apartment is 55 square meters, so realistically only two people can live here […]. We chose to register Stefan, because it would then be a man and a woman [i.e. the owner] living there. Then they would think it is a couple living there.

The second quote shows how Dorien and Stefan tactically utilised a combination of social capital as well as cultural capital (knowledge of and a willingness to game the official rules) to acquire an apartment. Yet, the two quotes also show how Dorien and her partner Stefan had to flexibly arrange and change their household status to find a home: first, by, as a couple, having to live together with other people and second, by faking a relationship with the owner of the apartment. Although they now live in a family apartment, their situation remains precarious, since Dorien cannot register at their living address. This is not only unpractical, but can also have juridical implications. Since the landlady aims to sell the apartment, she only gives yearly rent contracts. Hence, Dorien and Stefan remain in an unstable housing situation.

These examples illustrate how insecure housing arrangements are reproduced in subsequent housing arrangements, predominantly against the will of the respondents in this pathway. This situation persists as one insecure housing arrangement triggers a following insecure arrangement, for example due to an unexpected eviction. A series of unforeseen events and precarious housing arrangements thus tend to accumulate within the reproductive chaotic pathway. An important reason this insecure situation persists is the fact that these respondents are not able to get access to official sectors of the housing market, in contrast to those in the progressive chaotic housing pathway. The respondents in this sector do generally employ other forms of capital (social, cultural) to acquire housing, although, throughout, they depend on the tactical utilisation of these capitals to get hold of housing in an unplanned manner, in reaction to unplanned events.

Respondents in both chaotic pathways have to deal with constraints on the official segments of the housing market and circumvent them via the informal segments. Yet, respondents in the progressive pathways also see these informal segments as offering special qualities and possibilities that are not available in the official sector. Respondents in the reproductive chaotic pathway use informal segments to a greater extent as an escape route.

7 Discussion and conclusion

The current financial crisis and institutional changes in the housing market impose substantial constraints on access to housing for young people in various contexts. In high-demand urban contexts, processes of gentrification create an increasingly large gap between the preference for inner-city locations of young people and their opportunities to access these locations. Tenure conversions, liberalisation of the social-rental sector, and long waiting times for social dwellings make it increasingly difficult to pursue linear housing careers. This paper investigated how, over a longer period of time, young people navigate the increasingly constrained housing context of the city of Amsterdam. This paper addressed the question:

How do young people deal with constraints on the housing market, taking into account different forms of capital, and how does this influence the formation of different types of housing pathways?

Combining a pathway approach with the sociology of Bourdieu and De Certeau, we found that class differences and inequalities between ‘outsiders’ and ‘insiders’ of young people are reproduced on the Amsterdam housing market. Using interviews on individual housing biographies, we inquire into the longitudinal dimensions of the interplay between various forms of (official and unofficial) capital to gain access to housing. Defining three housing pathways—linear, progressive chaotic, and reproductive chaotic—this paper shows how similar housing arrangements tend to follow up on one another. Housing pathways are formed in the interaction of habitus and housing fields, leading to a series of housing practices (specific housing decisions, search behaviour) (Table 3).

We demonstrate that in spite of the many constraints, linear housing pathways continue to be possible for some young people. Even though most young people lack the currency (too little waiting time for social housing and only modest incomes), some manage to deploy other forms of capital allows them to pursue linear housing pathways. They strategically manoeuvre to gain an advantage over other households to access housing that would otherwise be out of reach. A relatively common strategy is to anticipate neighbourhood change, that is, the gentrification of particular neighbourhoods. By moving into gentrifying neighbourhoods at an early stage (Clay 1979), these respondents could be conceived of as pioneer or—in the case of students—as apprentice gentrifiers (Smith and Holt 2007) who employ cultural (and symbolic) capital, as well as social capital, facilitating the pursuit of a linear housing pathway.

Notwithstanding the occurrence of linear housing pathways, most young people follow (progressive) chaotic housing pathways (cf. Ford et al. 2002). Utilising mostly a combination of social and cultural capital (including gaming the system and even violating the law), these youngsters primarily search for housing in the informal circuit and the affordable private-rental sector (particuliere kernvoorraad). Strategic utilisation of these capital forms allows these people to improve upon their housing situation, eventually leading to a stable housing situation. The capital that is accumulated is then ‘transferred’ to the official sectors of the housing market. The progressive chaotic pathway furthermore shows how class differences can be spatially articulated even when economic capital is left out of the equation: the predominantly middle-class respondents, often originating from Amsterdam, are generally able to access several desirable apartments in up-market and gentrifying neighbourhoods due to other capitals at their possession. This relates to theories about marginal gentrification (Rose 1984; Van Criekingen and Decroly 2003) and also to broader conceptualisations of class and gentrification in which particularly the role of non-economic forms of capital is emphasised (Watt 2005; Bridge 2006; Boterman 2012b).

Young people with limited economic and other forms of capital at their disposal are more likely to become ‘trapped’ in a reproductive chaotic pathway and suffer various setbacks. These young people are generally ‘outsiders’—coming from outside the Amsterdam region and having little knowledge of the local housing market. Having fewer options, they tactically seize upon opportunities that come available within their own network—predominantly informal and temporary housing arrangements—as they do not have the ability to access official housing. This leads to a reproduction of their precarious housing situation, frequent evictions (related to the informal sector) reinforce, and reproduce the chaotic character of these households’ housing pathways.

Linear pathways for young people are rare, but it is important to stress that chaotic pathways should not necessarily be equated with marginality. Young people often deliberately choose for a chaotic housing pathway if this allows them to progress in the long run. Furthermore, it is also often a trade-off in which stability and playing by the official rules is forgone in exchange for location. A linear pathway is both less attractive and unattainable due to the necessity to have sufficient economic capital or waiting time. Further research should therefore further inquire into young peoples’ housing practices to better understand how different search behaviour can lead to different outcomes, potentially reinforcing (spatial) inequalities.

Notes

We focus on the age category of 18–35 year olds.

Individuals can register for social housing; yet, due to the limited number of dwellings becoming available, dwellings are assigned according to the duration of registration (i.e. waiting time).

In 2013, the rent cap however is subject to year-to-year changes.

Most agencies, including housing associations, ask new tenants in the private-rental sector to earn three or four times the rent. This is to ensure tenants can afford the monthly rent.

‘Kadaster collects and registers administrative and spatial data on property and the rights involved’, see: http://www.kadaster.nl/web/english.htm

Without her registration at this address, it would not be ‘owner-occupied’ anymore. Rent would then be taxable. Now, it looks like a form of cohabitation.

References

Berrington, A., Stone, J., & Falkingham, J. (2009). The changing living arrangements of young adults in the UK. Population Trends, 138, 27–37.

Boterman, W. R. (2012a). Deconstructing coincidence. How middle class households use various forms of capital to find a home. Housing, Theory & Society, 29(3), 321–338.

Boterman, W. R. (2012b). Residential mobility of urban middle classes in the field of parenthood. Environment and Planning A, 44, 2397–2412.

Boterman, W. R., Hochstenbach, C., Ronald, R., & Sleurink, M. (2013). Duurzame Toegankelijkheid van de Amsterdamse Woningmarkt voor Starters. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam.

Boterman, W. R., & Van Gent, W. P. C. (2014). Housing liberalization and gentrification. The social effects of tenure conversions in Amsterdam. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 105(2), 140–160.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. G. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241–258). New York: Greenwood.

Bridge, G. (2006). It’s not just a question of taste: Gentrification, the neighbourhood and cultural capital. Environment and Planning A, 38, 1965–1978.

Brown, L. A., & Moore, E. G. (1970). The intra-urban migration process: A perspective. Geografiska Annaler Series B, 52(1), 1–13.

Bugeja-Bloch, F. (2013). Residential trajectories of young French people: The French generational gap. In R. Forrest & N. M. Yip (Eds.), Young people and housing (pp. 179–198). Abingdon: Routledge.

Clapham, D. (2002). Housing pathways: a post modern analytical framework. Housing, Theory & Society., 19, 57–68.

Clapham, D. (2005). The meaning of housing: A pathway approach. Bristol: The Policy Press.

Clapham, D., Mackie, P., Orford, S., Buckley, K., & Thomas, I. (2012). Housing options and solutions for young people in 2020. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Clark, W. A. V., & Dieleman, F. (1996). Households and housing: Choice and outcomes in the housing market. New Brunswick: Center for Urban Policy Research, Rutgers University.

Clay, P. (1979). Neigborhood renewal: Resettlement and incumbent upgrading in American neighbourhoods. Lexington: DC Halth.

Chatterton, P. (1999). University students and city centres–the formation of exclusive geographies: The case of Bristol, UK. Geoforum, 30(2), 117–133.

De Certeau, M. (1984). The practice of everyday life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Dieleman, F. (2001). Modelling residential mobility; a review of recent trends in research. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 16, 249–265.

Dienst Wonen Amsterdam. (2008). De particuliere huursector en zijn bewoners. Amsterdam: Dienst Wonen Amsterdam.

Doling, J., & Ronald, R. (2010). Home ownership and asset-based welfare. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 25, 165–173.

Ford, J., Rugg, J., & Burrows, R. (2002). Conceptualising the contemporary role of housing in the transition to adult life in England. Urban Studies, 39(13), 2455–2467.

Forrest, R., & Kemeny, J. (1984). Careers and coping strategies: Micro and macro aspects of the trend towards owner occupation. Mimeo: University of Bristol.

Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and self identity; self and society in the late modern age. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Hamnett, C., & Randolph, B. (1988). Cities, housing and profits: Flat break-ups and the decline of private renting. London: Hutchinson.

Harloe, M. (1995). The People’s home? Social rented housing in Europe and America. Oxford/Cambridge: Blackwell.

Holt, L. (2008). Embodied social capital and geographic perspectives: performing the habitus. Progress in Human Geography, 32(2), 227–246.

Jacobs, K., Kemeny, J., & Manzi, T. (Eds.). (2004). Social constructionism in housing research. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Jones, G. (1987). Leaving the parental home: An analysis of early housing careers. Journal of Social Policy, 16(1), 49–74.

Kemeny, J. (1992). Housing and social theory. London: Routledge.

Kendig, H. L. (1984). Housing careers, life cycle and residential mobility: Implications for the housing market. Urban Studies, 21(3), 271–283.

Kintrea, K., & Clapham, D. (1986). Housing choice and search strategies within an administered housing system. Environment and Planning A, 18, 1281–1296.

Kleinhans, R. (2003). Displaced but still moving upwards in the housing career? Implications of forced residential relocation in the Netherlands. Housing Studies, 18(4), 473–499.

McKee, K. (2012). Young people. Homeownership and Future Welfare. Housing Studies, 27(6), 853–862.

McNamara, S., & Connell, J. (2007). Homeward bound?Searching for home in Inner Sydney’s share houses. Australian Geographer, 38(1), 71–91.

Mulder, C. H. (2006). Home-ownership and family formation. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 21, 198–281.

Mulder, C. H., & Lauster, N. T. (2010). Housing and family: An introduction. Housing Studies, 25, 433–440.

Musterd, S. (2014). Public housing for whom? Experiences in an era of mature neo-liberalism: The Netherlands and Amsterdam. Housing Studies. doi:10.1080/02673037.2013.873393.

Priemus, H. (1986). Housing as a social adaptation process: “A conceptual scheme”. Environment and Behavior, 18(1), 31–52.

Rose, D. (1984). Rethinking gentrification: Beyond the uneven development of marxist urban theory. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space., 1, 47–74.

Rugg, J. (2010). Young people and housing: The need for a new policy agenda. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Rugg, J., Ford, J., & Burrows, R. (2004). Housing advantage? The role of student renting in the constitution of housing biographies in the United Kingdom. Journal of Youth Studies, 7(1), 19–34.

Sage, J., Evandrou, M., & Falkingham, J. (2013). Onwards or homewards? Complex graduate migration pathways, wellbeing and the ‘parental safety net’. Population, Space and Place, 19, 738–755.

Smith, D., & Holt, L. (2007). Studentification and `apprentice’ gentrifiers within Britain’s provincial towns and cities: extending the meaning of gentrification. Environment and Planning A, 39, 142–161.

Van Criekingen, M., & Decroly, J. (2003). Revisiting the diversity of gentrification: Neighbourhood renewal processes in Brussels and Montreal. Urban Studies, 40(12), 2451–2468.

Van Der Veer, J., & Schuiling, D. (2005). The Amsterdam housing market and the role of housing associations. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 20, 167–181.

Van Gent, W. P. C. (2013). Neoliberalization, housing institutions and variegated gentrification: How the ‘Third Wave’ broke in Amsterdam. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37(2), 503–522.

Van Kempen, R., & Özüekren, A. S. (1998). Ethnic segregation in cities: New forms and explanations in a dynamic world. Urban Studies, 35(10), 1631–1656.

Watt, P. (2005). Housing histories and fragmented middle-class careers: The case of marginal professionals in London Council Housing. Housing Studies, 20(3), 359–381.

Williams, F., & Popay, J. (1999). Balancing polarities: Developing a new framework for welfare research. In F. Williams, J. Popay, & A. Oakley (Eds.), Welfare Research: A Critical Review. London: UCL Press.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Ministry of the Interior for funding the research; Marijn Sleurink, Richard Ronald, Sako Musterd, Robbin-Jan van Duijne for collaborating on this research project; and three anonymous referees for useful suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hochstenbach, C., Boterman, W.R. Navigating the field of housing: housing pathways of young people in Amsterdam. J Hous and the Built Environ 30, 257–274 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-014-9405-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-014-9405-6