Abstract

Chagas disease (CHD) has become a challenge in Spain due to the high prevalence of immigrants coming from endemic areas. One of the main difficulties for its control and elimination is its underdiagnosis. The identification and integral treatment of CHD are key to increasing rates of diagnosis, overcoming psycho-social barriers and avoiding CHD progression. Community interventions with in situ screening have proven to be a useful tool in detecting CHD among those with difficulties accessing health services. To determine the underdiagnosis rate of the population most susceptible to CHD among those attending two different Bolivian cultural events celebrated in Barcelona; to describe the sociodemographic characteristics of the people screened; and to analyse the results of the screening. The community interventions were carried out at two Bolivian cultural events held in Barcelona in 2017. Participants were recruited through community health agents. A questionnaire was given to determine the participants’ prior knowledge of CHD. In situ screening was offered to those who had not previously been screened. Those who did not wish to be screened were asked for the reason behind their decision. Results were gathered in a database and statistical analyses were performed using STATA v14. 635 interviews were carried out. 95% of the subjects reported prior knowledge of CHD. 271 subjects were screened: 71.2% women and 28.8% men, of whom 87.8% were of Bolivian origin. The prevalence of CHD was 8.9%. Community health interventions with in situ screening are essential to facilitating access to diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Chagas disease (CHD) is a growing concern in non-endemic countries [1], specifically in Spain, the country with the highest prevalence of this disease in Europe [2,3,4]. It is estimated that between 6 and 7 million people are infected with Trypanosoma cruzi worldwide, the majority being from Latin America [5]. Spain is the European country with the largest population of immigrants coming from Latin America, including Bolivia, the country with the highest prevalence of infection by T. cruzi in the Americas. For this reason, Spain has a greater estimated number of infected people than any other European country and even some countries in the Americas [6,7,8].

The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies CHD as one of the 21 Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTD) and one of the main difficulties for its control and elimination is its severe underdiagnosis. It is currently estimated that, worldwide, less than 10% of infected patients have been diagnosed with CHD [2,3,4,5, 9]. Overcoming barriers of access to diagnosis is crucial to reversing this problem [10].

In the case of CHD, psycho-social and cultural determinants clearly act as a barrier against access to the diagnosis and treatment of the disease, not just for affected patients but also for their families and society in general [11, 12]. Debunking the myth that CHD is terminal, and therefore working toward relative societal normalcy as well as advocating for the diagnosis and treatment of this disease, has important effects on health from both a psychological and social standpoint [10].

Screening is fundamental for the diagnosis of CHD at any stage of the disease. Early detection allows patients to begin antiparasitic treatment, which becomes less effective in later stages of the disease. Diagnosis in the later chronic phase is also important in order to offer integral management of the disease, and to promote secondary and tertiary prevention of CHD and its complications, which helps to break down the psycho-social barriers in a more effective way. Screening is also imperative in order to stop human-to-human spread of CHD, such as through congenital transmission and transmission through donated blood [13].

Since 2005, in Spain, CHD has been screened in blood donors coming from countries with high endemicity [14]. In Catalonia, a 0.62% seroprevalence of CHD was observed in all at-risk donors, and a seroprevalence of up to 10.2% was seen in donors coming specifically from Bolivia [15]. In 2010, Catalonia implemented the Chagas Disease Screening Programme for pregnant women coming from Latin American countries. Between 2010 and 2012, this screening programme showed a prevalence of this disease in 1.8% of all screened Latin American women and 10.2% in Bolivian women, with a congenital transmission rate of 3.9% overall and 4.2% in Bolivians [16].

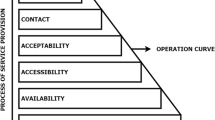

Since 2004, the International Health Unit Drassanes-Vall d’Hebron (USIDVH) Public Health and Community Team (eSPiC) has worked to carry out community interventions with the aim of confronting access barriers to CHD screening, treatment, and prevention. The interventions have been implemented in collaboration with NGOs such as Asociación de Amigos de las personas afectadas por la enfermedad de Chagas (ASAPECHA, Association of Friends of Chagas-Affected Patients).

Community interventions based on this psycho-social approach have proven to be the most useful, as they allow the identification of patients who experience barriers to healthcare service access. They also facilitate screening, treatment, follow-up care, and community awareness and mobilization in relation to CHD [9, 17].

Objectives

The objectives of this study are:

-

1.

To determine the rate of underdiagnosis of Chagas disease in the susceptible population that attended two different Bolivian cultural events celebrated in Barcelona.

-

2.

To describe the sociodemographic characteristics of the immigrants coming from endemic areas who were screened for CHD in in situ screening interventions performed in Barcelona and the impact of these interventions on the targeted population, at both the diagnostic and treatment levels.

Methods

The present work has been carried out in the Metropolitan Area of Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain. In the Autonomous Community of Catalonia in 2017, a total of 27,562 Bolivians were counted (the total population of the region that year was 7,496,276 inhabitants, with 1,146,319 of those being foreigners) of which 23,148 lived in the province of Barcelona [18].

Two community interventions were performed at Bolivian cultural events celebrated in Barcelona in 2017–one on the 16th of July at a Los Kjarkas Bolivian folk band concert, and one on the 6th of August during a concert in celebration of Bolivian National Day. The attendees of those events were mostly of Bolivian origin, but some were from other countries in Latin America where CHD is also highly present. Those specific cultural events were chosen because the highest prevalence of CHD in non-endemic countries is among Bolivian immigrants, and those two events attract the highest number of Bolivians in the metropolitan area of Barcelona [2, 15].

All attendees coming from endemic areas were eligible to participate in the screening. Participants were recruited by community health agents and peer-to-peer educators from ASAPECHA who had been previously trained in the comprehensive approach to the disease, working in a particular way on the psycho-social aspects that make access to CHD diagnosis difficult.

These community health agents and peer-to-peer educators interviewed the participants and informed them about CHD, the barriers to healthcare access, and the importance of CHD diagnosis and treatment.

First, the participants were asked a series of questions to assess their prior knowledge of CHD and to determine if they had been previously screened for the illness. If they had been tested before, they were asked why (interventions done by other agencies or health centers, routine pregnancy screening, family history of CHD, awareness of the disease, etc.) and where they were screened (primary healthcare center, international health/tropical medicine units, or hospitals) (Supplemental material 1). The answers that the participants gave during this interview allowed their interviewers to identify and think critically about the specific barriers that each participant had in relation to the performance of the screening. The interviewers were then able to direct their conversations with the participants by giving information that was more relevant to their concerns.

Afterward, those participants who had not been previously tested were offered the chance of being screened in situ. Those who rejected the screening were asked for the reason behind their decision. A blood test was performed for those who wished to be screened by the mobile teams of the Blood and Tissue Bank of Catalonia. The blood collected was tested for serological determination of T. cruzi following WHO guidelines [19]. All serum samples were tested for one recombinant antigen EIA (CHAGAS ELISA IgG+IgM, Vircell, Spain) and all of those with an index > 0.9 were tested for one lysate antigen EIA simultaneously (ORTHO Trypanosoma cruzi ELISA Test System, Johnson and Johnson, USA). To establish a diagnosis of CHD, the results of both techniques needed to be concordant in all cases, with an index > 0.9, which is considered a reactive serology. The patients with a positive result on the screening test were contacted by telephone and directed to the USIDVH to determine the possibility of cardiac and/or digestive involvement, as well as to initiate antiparasitic treatment and bio-psycho-social follow-up care.

All the subjects who were interviewed gave informed verbal consent to participate in the study and also in the in situ screening. Verbal consent to participate was used rather than written consent as it was part of the conventional protocol of screening and follow-up of susceptible to Chagas Disease patients of our clinics. The procedures performed during the screening are the ones recommended by the WHO. No data containing personal or identifying information from the participants has been published. The Ethical Committee of Vall d’Hebron Hospital approved the study from an Ethical and Scientific point of view (number 339) (Supplemental Material 2).

The statistical analyses were performed using Stata v14 (StataCorp. 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP). Median and interquartile range (IQR) as well as count and percentage were used for the description of quantitative variables and qualitative variables, respectively. To assess the association between the different variables, the Chi squared test and the Fisher’s exact test were performed.

Results

A total of 635 interviews were conducted at the two previously mentioned Bolivian cultural events. Among the participants, 92.5% (587/635) were of Bolivian origin. Prior knowledge of CHD was reported in 604 (95%) of the interviewed subjects.

According to the interviews, up to 288 participants (45.4%) reported previous screening, which meant an underdiagnosis index of 54.6%. Among those who reported previous screening, 33% (95/288) were screened at Vall d’Hebron University Hospital or at Hospital Clínic of Barcelona; 21.2% (61/288) at USIDVH as part of a previous community intervention; 8% (23/288) in their Primary Healthcare Center either in the city of Barcelona or in other municipalities in the Catalonia region; and the remaining 37.8% (109/288) in other settings.

Of the 347 participants who had not previously been screened, up to 21.9% (76/347) did not wish to take the test: 71.1% (54/76) because they were in a festive environment, 17.1% (13/76) for fear of blood removal, and 11.8% (9/76) for other reasons (Fig. 1).

In total, 271 screening tests were performed. The median age was 38 years old (IQR 31–44). Among those screened, 71.2% (193/271) were women and 28.8% (78/271) men. Up to 87.8% of the participants (238/271) were born in Bolivia (43.5% from the Department of Cochabamba, 31.7% from the Department of Santa Cruz and 24.8% from other Bolivian provinces), whose average length of residence in Spain was 11 years (IQR 10–13) (Table 1).

The test was positive in 8.9% (24/271) of the people screened, of whom 23 were Bolivian and 1 was Argentinian. The age group with the highest number of positive results in the screening test was 50–59 years (41.7% of the total positive results). In 75% (18/24) of the participants with a positive result, the residence time in Spain was higher than 10 years. A total of 75% (18/24) of the positive results were in women (Table 2).

Using the Fisher’s exact test, the existence of a statistically significant association between age and the positive result of the test was observed (p < 0.005).

The 24 patients with positive serologies were contacted by telephone to attend an initial visit at the health centre to assess their condition, and then to be given a study of systemic involvement, such as heart and/or digestive disease. They were to be administered treatment over a period of time and to be given follow-up care. Of those 24 patients, 87.5% (21/24) attended that first visit at the USIDVH and 76.2% (16/21) of those patients completed the study of systemic involvement. Two of the 16 patients studied had cardiac disease (cardiomegaly) and two presented with digestive disease (dolicosigma, dolicocolon, and delayed esophageal emptying). Four patients with positive serologies did not present themselves at the health centre in Barcelona–one was examined in a health centre of another autonomous community, completed treatment and follow-up there, and is counted in the 21 participants; and three did not respond after three attempts at contact by telephone. Thirteen of those 21 participants who attended their initial health centre visit received treatment, and by March 2019, 12 of them had finished it and completed follow-up care successfully. Only one patient did not attend further health centre visits after 15 days of treatment.

Discussion

The results obtained in this study are comparable to those observed in other community interventions performed to screen CHD in susceptible populations. Community interventions are group activities planned and carried out in a collaborative manner in the community and aimed at improving health and well-being [20]. In the case of CHD, where the psycho-social factors established in the community have great relevance, this work becomes fundamental when it comes to rebuilding perceptions of the disease and eliminating stigma across the population. In situ screening interventions performed in 2014 during the Bolivian National Day in Barcelona have previously been published by our group [9]. Other community interventions for the recruitment of patients upon which to carry out screening tests have been described in workshops in Bergamo, Italy performed in 2012 and in 2013 [21]; informative group talks given in Madrid, Jerez de la Frontera, and Alicante, Spain between 2007 and 2010 [22]; and the use of informative brochures as well as the conduction of workshops at Bolivian community events in Munich, Germany in the years 2013 and 2014 [23].

In the present study, we observed an underdiagnosis index of 54.6%, lower than what had been reported in previous studies. According to the previously mentioned WHO publication, using data from 2009, the underdiagnosis index in Europe ranged from 93.9 to 96.4%, which was between 92.0 and 95.6% in Spain [2]. In the previous intervention carried out in Barcelona in 2014 [9], of the 169 people recruited for the in situ screening, 30 (17.7%) were excluded as they reported having already been given a CHD diagnostic test, establishing an underdiagnosis index of 82.3%. Using this data from the city of Barcelona, it can be stated that there is a decreasing trend in the phenomenon of underdiagnosis, going from 82.3 to 54.6%, with lower rates than the ones observed in the rest of the Spanish regions as well as in other European countries. The underdiagnosis of CHD is mostly due to its asymptomatic clinical presentation and the presence of psycho-social barriers to diagnostic access at early stages, to treatment, and to clinical follow-up care, all of which contribute to a worsening prognosis of the disease.

In our study, we observed that 33% of the people who had previously been screened were studied in two high-complexity hospitals with specialized Tropical Medicine units. This is largely a result of the aforementioned screening for congenital CHD in the maternity units, the screening performed on blood donations at the Blood and Tissue Bank, and also as part of the study performed on relatives of a CHD index case. Up to 21.2% of the patients reported being screened previously at the USIDVH, most as part of a previous community intervention. This fact highlights the importance of such interventions in our community as well as the importance of a multidisciplinary approach involving healthcare workers, community health agents, and peer-to-peer educators in order to improve recruitment, patient follow-up, and to ensure an increased effectiveness of these actions. Finally, it should be noted that only 8% of those previously diagnosed came from the Primary Healthcare Centers, suggesting that the Catalan health system has not effectively incorporated the screening of this disease into its regular disease protocol, likely due to the primary healthcare practitioners’ lack of knowledge [24].

As discussed above, in our intervention 635 people were interviewed and 271 were screened during two different community events that lasted for 1 day each. In the in situ screening conducted in 2014 [9], the same team on 1 day interviewed a total of 169 people, screening 131 of them (77.5%) and obtaining up to 26.7% positive results in the serological tests performed. Other community interventions conducted have obtained a lower recruitment of patients: in Italy, 1305 people were screened as a result of different workshops carried out over a year (3–4 people per day) [21] and in Madrid, 352 people were tested after 44 workshops were carried out over two and a half years (8 people per workshop) [22], which could be considered, a priori, a greater recruitment effort.

The recruitment of people susceptible to T. cruzi infection for the screening of CHD is a challenge as the target population faces significant psycho-social barriers that are difficult to overcome, especially a lack of accurate information about the disease which includes the myth that CHD is always fatal [10]. The involvement of civil society organizations such as ASAPECHA, the participation of peer-to-peer educators previously trained in the Catalonian Expert Patient Programme for Chagas Disease [25], and the involvement of a multidisciplinary community health team, as well as using community strategies based on socio-anthropological studies on the sociocultural and psychosocial aspects of the disease, are key elements to facilitating the recruitment of people and enhancing access to diagnosis [26].

The prevalence of the disease in the present study was 8.9%, lower than in other studies conducted in the same city in 2015, which observed a prevalence of 18.1% in the Bolivian population and of 4.2% in the whole set of the Latin American population [27]. Other studies [6, 8, 9, 22, 28] show even higher prevalences. Our results are similar to those obtained in blood donors of Bolivian origin in Catalonia in 2008 (10.2%) [15] and in the screening study conducted in Germany (9.3%) [23].

We attribute this decrease in CHD prevalence in our region to multiple factors. The fact that we observe an increase in the average age of positive cases could indicate that young people have been previously screened or that the immigration process has decreased from endemic areas to our country [29, 30]. The disease control policies that are currently being implemented in Bolivia may also be showing their impact—young people in endemic areas of Bolivia may have a lower risk of contracting CHD, which means that the disease is less likely to follow them should they choose to emigrate to Barcelona [29, 30].

Regarding the patients’ follow-up care, we observed that 87.5% of the 24 patients with positive serological results came to the health center for an initial visit and 76.2% underwent the systemic involvement study. In the present study, 52.2% of the patients who completed the study also successfully finished their treatment and follow-up care. In the previous in situ screening intervention performed by our group [9], 57.2% of the patients followed subsequent checkpoints. In the study conducted in Barcelona as part of the congenital Chagas programme, out of a total of 179 pregnant women, 43 newborns failed to attend monitoring visits (24%). After the intervention of community health agents, however, 31 of those children returned to the study, of whom 14 had not been tested for T. cruzi infection [31]. In the study carried out in Madrid [22], of the 44 positive cases (15.9% of the total of tests), 70.5% of the patients received follow-up care. In the study conducted in Italy, the failure of patients with positive results to attend consultation was even higher; 49% of the patients [21] did not come. In the literature reviewed, information regarding treatment follow-up and its completion was not available. It is also necessary to develop new strategies to improve monitoring of the patients and their treatment after the diagnosis of Chagas disease.

Conclusions

Community health interventions, especially in situ screening interventions, are highly useful to improve access to screening, to increase knowledge of CHD, and to combat the psycho-social barriers to its diagnosis. The intervention explained in this article is a viable way of screening these populations as it appears to have advantages over other methods. The bio-psycho-social and multidisciplinary approach of this intervention implies the necessity of an improvement in the follow-up care of the patients and in the effectiveness of the actions conducted.

Abbreviations

- CHD:

-

Chagas Disease

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- NTD:

-

Neglected Tropical Diseases

- USIDVH:

-

International Health Unit Drassanes-Vall d’Hebron

- eSPiC:

-

Public Health and Community Team

- ASAPECHA:

-

Asociación de Amigos de las personas afectadas por la enfermedad de Chagas - Associations of Friends of Chagas affected patients

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

References

World Health Organization. Chagas epidemiology [Internet]. World Health Organization. Retrieved March 31, 2019, form http://www.who.int/chagas/epidemiology/en/

Basile, L., Jansa, J. M., Carlier, Y., Salamanca, D. D., Angheben, A., Bartoloni, A., et al. (2011). Chagas disease in European countries: the challenge of a surveillance system. Eurosurveillance, 16(37), 19968.

Gascon, J., Bern, C., & Pinazo, M.-J. (2010). Chagas disease in Spain, the United States and other non-endemic countries. Acta Tropica, 115(1–2), 22–27.

Schmunis, G. A., & Yadon, Z. E. (2010). Chagas disease: A Latin American health problem becoming a world health problem. Acta Tropica, 115(1–2), 14–21.

World Health Organization. Integrating neglected tropical diseases in global health and development [Internet]. World Health Organization. Retrieved March 31, 2019, from http://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/resources/9789241565448/en/

Pérez-Ayala, A., Pérez-Molina, J. A., Norman, F., Navarro, M., Monge-Maillo, B., Díaz-Menéndez, M., et al. (2011). Chagas disease in Latin American migrants: A Spanish challenge. Clinical Microbiology & Infection, 17(7), 1108–1113.

Muñoz, J., Gómez i Prat, J., Gállego, M., Gimeno, F., Treviño, B., López-Chejade, P., et al. (2009). Clinical profile of Trypanosoma cruzi infection in a non-endemic setting: Immigration and Chagas disease in Barcelona (Spain). Acta Tropica, 111(1), 51–55.

Navarro, M., Navaza, B., Guionnet, A., & López-Vélez, R. (2012). Chagas disease in Spain: Need for further public health measures. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 6(12), e1962.

Ouaarab Essadek, H., Claveria Guiu, I., Caro Mendivelso, J., Sulleiro, E., Pastoret, C., Navarro, M., et al. (2017). Cribado in situ de la enfermedad de Chagas con una intervención comunitaria: ¿puede mejorar la accesibilidad al diagnóstico y al tratamiento? Gaceta Sanitaria, 31(5), 439–440.

Avaria, A., & Gómez i Prat, J. (2008). Si tengo Chagas es mejor que me muera: el desafío de incorporar una aproximación sociocultural a la atención de personas afectadas por la enfermedad de Chagas. Enferm Emergency, 10, 40–45.

Minneman, R. M., Hennink, M. M., Nicholls, A., Salek, S. S., Palomeque, F. S., Khawja, A., et al. (2012). Barriers to testing and treatment for chagas disease among latino immigrants in Georgia. Journal of Parasitology Research, 2012, 295034.

Manne-Goehler, J., Reich, M. R., & Wirtz, V. J. (2015). Access to care for chagas disease in the United States: A health systems analysis. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 93(1), 108–113.

Carlier, Y., Sosa-Estani, S., Luquetti, A. O., & Buekens, P. (2015). Congenital chagas disease: An update. Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, 110(3), 363.

Real Decreto 1088/2005, de 16 de septiembre [Internet]. Retrieved March 31, 2019, from http://sid.usal.es/leyes/discapacidad/8179/3-1-5/real-decreto-1088-2005-de-16-de-septiembre-por-el-que-se-establecen-los-requisitos-tecnicos-y-condiciones-minimas-de-la-hemodonacion-y-de-los-centros.aspx

Piron, M., Vergés, M., Muñoz, J., Casamitjana, N., Sanz, S., Maymó, R. M., et al. (2008). Seroprevalence of Trypanosoma cruzi infection in at-risk blood donors in Catalonia (Spain). Transfusion, 48(9), 1862–1868.

Basile L. (2015). Un exemple de coordinació entre diferents àmbits assistencials: el Programa de cribratge de la malaltia de Chagas congènita a Catalunya. VIGILÀNCIA 2.0 [Internet]. 5a Jornada del Pla de salut de Catalunya, Sitges. Retrieved March 31, 2019, from http://jornadapladesalut.canalsalut.cat

Velarde-Rodríguez, M., Avaria-Saavedra, A., Gómez-i-Prat, J., Jackson, Y., de Oliveira, W. A., Jr., Camps-Carmona, B., et al. (2009). Need of comprehensive health care for T. cruzi infected immigrants in Europe 25a Reuniao Annual de Pesquisa Aplicada em Doença de Chagas. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical, 42(Suppl II), 92–95.

Institut d’Estadística de Catalunya - IDESCAT (Catalan Statistics Institute). [Internet]. Retrieved March 31, 2019, from https://www.idescat.cat/

World Health Organization. More on Chagas disease diagnosis [Internet]. World Health Organization. Retrieved March 31, 2019, from http://www.who.int/chagas/disease/home_diagnosis_more/en/

Cassetti, V., López-Ruiz, V., Paredes-Carbonell, J. J., Grupo de Trabajo del Proyecto AdaptA GPS. (2018). Participación comunitaria: mejorando la salud y el bienestar y reduciendo desigualdades en salud. Zaragoza: Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar Social – Instituto Aragonés de Ciencias de la Salud.

Repetto, E. C., Zachariah, R., Kumar, A., Angheben, A., Gobbi, F., Anselmi, M., et al. (2015). Neglect of a neglected disease in Italy: The challenge of access-to-care for chagas disease in Bergamo Area. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 9(9), e0004103.

Navarro, M., Perez-Ayala, A., Guionnet, A., Perez-Molina, J. A., Navaza, B., Estevez, L., et al. (2011). Targeted screening and health education for Chagas disease tailored to at-risk migrants in Spain, 2007 to 2010. Eurosurveillance, 16(38), 19973.

Navarro, M., Berens-Riha, N., Hohnerlein, S., Seiringer, P., von Saldern, C., Garcia, S., et al. (2017). Cross-sectional, descriptive study of Chagas disease among citizens of Bolivian origin living in Munich, Germany. British Medical Journal Open, 7(1), e013960.

Claveria, I., Caro, J., Ouaarab, H., Treviño, B., Serre, N., Pou, D., et al. (2015). Knowledge about Chagas disease of patients and health professionals in a non-endemic areas: are there differences? Oral communication (O.4.2.3.004) at the)th European Congress on Tropical Medicina and International Health. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 20(Suppl.1), 90–91.

Claveria Guiu, I., Caro Mendivelso, J., Ouaarab Essadek, H., González Mestre, M. A., Albajar-Viñas, P., & Gómez i Prat, J. (2017). The Catalonian expert patient programme for chagas disease: An approach to comprehensive care involving affected individuals. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 19(1), 80–90.

Sanmartino, M., Amieva, C., & Medone, P. (2018). Representaciones sociales sobre la problemática de Chagas en un servicio de salud comunitaria del Gran La Plata, Buenos Aires, Argentina. Global Health Promotion, 25(3), 102–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757975916677189.

Requena-Méndez, A., Aldasoro, E., de Lazzari, E., Sicuri, E., Brown, M., Moore, D. A. J., et al. (2015). Prevalence of chagas disease in Latin-American migrants living in Europe: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 9(2), e0003540.

Jackson, Y., Gétaz, L., Wolff, H., Holst, M., Mauris, A., Tardin, A., et al. (2010). Prevalence, clinical staging and risk for blood-borne transmission of chagas disease among Latin American migrants in Geneva, Switzerland. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 4(2), e592.

Dias, J., Silveira, A., & Schofield, C. (2002). The impact of Chagas disease control in Latin America: a review. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, 97(5), 603–612.

Dias, J. (2007). Southern Cone Initiative for the elimination of domestic populations of Triatoma infestans and the interruption of transfusional Chagas disease. Historical aspects, present situation, and perspectives. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, 102, 11–18.

Soriano-Arandes, A., Basile, L., Ouaarab, H., Claveria, I., Goméz-Prat, J., Cabezos, J., et al. (2014). Controlling congenital and paediatric chagas disease through a community health approach with active surveillance and promotion of paediatric awareness. BMC Public Health, 14(1), 1201.

Acknowledgements

To the patients who participated in the community interventions, to ASAPECHA for the community work performed and to all the professionals involved in the in situ interventions and the development of the interviews. To Alexandra Craddock for the English editing of the manuscript.

Funding

This intervention was partially funded by the NGO Fundación Mundo Sano – España, financing part of the promotional material of the community intervention. The design of the study and the collection, the data analysis and its interpretation has not been funded.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to conception and design of the intervention and acquisition of data. JGP, ICG, EC, IOS, NSD, CP, JJS and HO designed the in situ screening intervention. CP was the responsible for the intervention logistics. JGP, ICG, EC, IOS, NSD and HO interviewed the participants and collected the interview data. JGP, PPT and IOS collected the clinical data. ES and ME performed the laboratory tests. JGP, ICG, EC, IOS and HO participated in the follow-up of the patients. PPT performed the data analysis. All authors discussed the results obtained and the intervention performed. PAV and CAT contributed to the interpretation of the results. JGP and PPT wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors have revised critically the article for intellectual content. JGP and PPT wrote the final version of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the submitted manuscript. JGP and PPT are first co-authors of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare not having any potential conflict of interest to declare.

Ethics Approval

The Ethical Committee of Vall d’Hebron Hospital approved the study from an Ethical and Scientific point of view (number 339) (Supplemental Material 2).

Informed Consent

All the subjects who were interviewed gave informed verbal consent to participate in the study and also in the in situ screening. Verbal consent to participate was used rather than written consent as it was part of the conventional protocol of screening and follow-up of susceptible to Chagas Disease patients of our clinics. The procedures performed during the screening are the ones recommended by the WHO. No data containing personal or identifying information from the participants has been published.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gómez i Prat, J., Peremiquel-Trillas, P., Claveria Guiu, I. et al. A Community-Based Intervention for the Detection of Chagas Disease in Barcelona, Spain. J Community Health 44, 704–711 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-019-00684-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-019-00684-z