Abstract

Among a sample of sheltered homeless women, we examined health, access to health care, and health care use overall and among the subgroup of participants with and without intimate partner violence (IPV). We recruited homeless women from a random sampling of shelters in New York City, and queried them on health, access to health care and health care use. Using multivariable logistic regression, we determined whether IPV was associated with past-year use of emergency, primary care and outpatient mental health services. Of the 329 participants, 31.6% reported one or more cardiovascular risk factors, 32.2% one or more sexually transmitted infections, and 32.2% any psychiatric condition. Three-fourths (73.5%) had health insurance. Health care use varied: 55.4% used emergency, 48.9% primary care, and 75.9% outpatient mental health services in the past year. Across all participants, 44.7% reported IPV. Participants with IPV compared to those without were more likely to report medical and psychiatric conditions, and be insured. Participants with IPV reported using emergency (64.4%) more than primary care (55.5%) services. History of IPV was independently associated with use of emergency (Adjusted odds ratio (AOR) 1.7, 95% CI 1.0–2.7), but not primary care (AOR 1.5, 95% CI 0.9–2.6) or outpatient mental health services (AOR 1.9, 95% CI 0.9–4.1). Across the whole sample and among the subgroup with IPV, participants used emergency more than primary care services despite being relatively highly insured. Identifying and eliminating non-financial barriers to primary care may increase reliance on primary care among this high-risk group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Homeless women experience high rates of intimate partner violence (IPV) [1–3], with prevalence ranging between 30 and 90% [1–6]. Co-occurring mental illness and substance use disorders [1, 2, 7–9], combined with medical co-morbidities increase risk for poor health outcomes and premature mortality among this population [10–13]. Homeless women experience barriers to needed medical care [9, 14–16], lack a regular source of health care and insurance [17] and have decreased access to women’s preventive health services [14].

Women experiencing IPV report elevated rates of depression [18], post-traumatic stress disorder [19], and substance use disorders [4]. They are more likely to have sexually transmitted infections [4, 20–22], chronic pain [19, 21, 22], and cardiovascular disease [23, 24]. Women experiencing IPV have high rates of health care use [25], and report barriers to receiving needed medical care [19, 26], relying mostly on emergency services [27].

While studies have independently shown health characteristics, access to health care and health care use among women experiencing homelessness or IPV, there are few studies that have examined these outcomes among homeless women experiencing IPV. Given the independent health risks of homelessness and IPV, the combination of the two may augment adverse health outcomes and inappropriate health care use.

In this study, we described health characteristics, access to health care, and health care use among homeless women recruited from shelters, and compared these outcomes among subgroups with and without a history of IPV (defined as physical assault by an intimate partner). We examined the association between past or current IPV and past-year use of emergency, primary care and outpatient mental health services, adjusting for predisposing, need and enabling factors obtained from the Gelberg-Anderson Behavioral Model for Health Care Utilization in Vulnerable Populations [9, 28]. We hypothesized that homeless women with a past or current history of IPV would have higher rates of acute and chronic disease and health care use characterized by a reliance on emergency medical services over primary care. Previous studies describing these outcomes among homeless women were conducted between 1993 and 1997 in two US cities [7, 9, 12, 15–17, 29]. While recent data on health care access and utilization exists for homeless adults overall [30, 31], homeless women comprise a minority among these samples. Our study conducted between 2007 and 2008 may offer new insights into these health outcomes for sheltered homeless women and subgroups with and without a history of IPV.

Methods

Study Design and Procedures

Using data from the HIV Risk among Homeless Women Study, we conducted a cross-sectional analysis examining health, access to health care, and health care use among a sample of homeless women, and compared these outcomes between women with and without a history of IPV. The goal of the HIV Risk among Homeless Women Study was to biologically confirm the presence of HIV (Orasure fluid test with Western blot confirmatory test), Chlamydia, and gonorrhea (urine tests), and obtain self-reported information on previous sexually transmitted infections (STI). Homeless women living in shelters located throughout the four New York City boroughs were recruited for the study between 2007 and 2008. To enroll in the study, women had to be ≥18 years of age, speak either fluent English or Spanish, and provide informed consent. Trained research staff conducted HIV and STI testing and study interviews onsite at the shelter facilities (34 interviews were conducted at the office). Study sampling occurred in two phases. During the first phase, 28 shelters (emergency and transitional) were randomly selected from a total of 126 facilities in New York City. The 28 shelters were stratified by shelter type (e.g., shelters for families with children, shelters for families made up of two or more adults, shelters for single adults with or without services for people with mental illness or substance abuse) and size (under 40 units, over 40 units). Within each stratum, shelters were sampled with probability proportional to sample size. In the second phase, bed or room numbers were randomly selected from each of the 28 selected shelters. Research staff mailed a description of the study to residents occupying the selected bed or room, and requested interested participants to contact them during an on-site scheduled visit. Each study participant received a gift card valued between $35 and $50 for participation in the study. The Columbia University Medical Center and New York City Department of Homeless Services Institutional Review Boards approved all study procedures.

Intimate Partner Violence

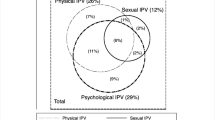

The primary independent variable was intimate partner violence (IPV), defined as physical assault by an intimate partner (boyfriend, girlfriend or spouse). Participants who self-reported a previous history of, or ongoing IPV were coded as having experienced IPV.

Health Care Use

Participants were asked whether they had visited a primary care provider (PCP), emergency department (ED), obstetrician/gynecologist (Ob/Gyn), an eye doctor, dentist, or another doctor in the past year. Those who answered affirmatively to each medical visit were coded as having had a visit with each type of provider in the past year. We reported the proportion of participants who received preventive care services such as a pap smear in the past year. Participants who reported seeing a mental health provider for a non-addiction based emotional problem, or who sought an outpatient psychiatric or rehabilitation program in the past year were coded as having used outpatient mental health. The primary health care utilization outcome variables for our multivariable analysis were use of emergency, primary care and outpatient mental health services in the past year.

Covariates

We ordered covariates by predisposing, enabling and need characteristics using the previously described Gelberg-Anderson Behavioral Model for Health Care Utilization in Vulnerable Populations [9, 28]. Briefly, the model posits that health care use in vulnerable populations is predicated upon predisposing, enabling or need factors [9, 28]. Predisposing factors included age, race/ethnicity (White, African American, Hispanic/Latino, and Other), education (less than high school, high school, and more than high school), marital status (married/partnered vs. not), foster care placement, juvenile detention, lifetime history of incarceration, lifetime history of substance use (ever using cocaine, heroin or amphetamine vs. not), lifetime history of alcohol use (ever drinking more than 4 drinks at one sitting vs. not), tobacco use (current smoking vs. former or never), any psychiatric condition (health care providers’ diagnosis of any psychiatric condition vs. not), history of childhood physical or sexual abuse, and prior history of homelessness (prior history of staying at a shelter or in places unintended for sleeping in the past 2 years vs. only current episode).

Enabling factors included access to health care variables such as health insurance (current insurance vs. not) and whether or not participants had a preferred medical provider. Other variables included income from employment and welfare support in the past 6 months (receipt of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families benefits vs. not).

Need factors included presence of one or more cardiovascular risk factors (health care providers’ diagnoses of diabetes, hypertension or obesity vs. none), infectious diseases (health care providers’ diagnoses of HIV, Tuberculosis, Hepatitis B or C vs. none), and STI (health care providers’ diagnosis of syphilis, Gonorrhea, genital herpes, Chlamydia, Trichomoniasis, genital warts, or any other STI vs. none).

Statistical Analysis

We described predisposing, enabling and need factors for all participants, and compared these factors for participants with and without a history of IPV using the Chi-square test for categorical variables and t test for continuous variables. We described health care use among all participants and, in bivariate analysis, examined the association between IPV status and past-year health care use. Using multivariable logistic regression, we examined the association between IPV status and use of emergency, primary care and outpatient mental health services in the past year. We constructed models in a step-wise manner, adding singly and in order, those predisposing, enabling and need variables that were associated with the outcome at P < 0.1 in bivariate analysis [32]. We retained the newly added variable if its association with the outcome was significant at P < 0.05. If the new variable rendered a previously added variable insignificant, we removed that variable from the model. We retested all the variables removed in a previous step for addition to the models at P < 0.05. We conducted all analyses using Stata, version 11.

Results

Of the 675 participants (360 from single adult shelters and 315 from family shelters) who were initially selected through the random draw, 189 (28%) declined participation or did not attend the scheduled interview, and 155 (23%) were unable to be contacted despite multiple visits to the same facility by research staff. This resulted in a final analytic sample of 329 participants (49% overall response rate).

Across the whole sample, the mean age was 37.9 years, 45.3% were African American, and 48.2% had less than a high school education (Table 1). Most (67.2%) of the participants had a prior history of homelessness, and half (50.0%) were current smokers. Across all participants, 31.6% reported one or more cardiovascular risk factors: 9.8% had diabetes, 10.1% had obesity, and 23.3% had hypertension. A third of the participants had been diagnosed with one or more STI (32.2%) or any psychiatric condition (32.2%). For access to care variables, 73.5% reported being insured and 65.3% had a preferred medical provider. With the exception of outpatient mental health services use, which was restricted to 199 participants who responded to those questions, sample sizes for all other health care use outcomes was 329. Health care use varied with 55.4% of participants reporting an ED visit, 48.9% a PCP visit, 51.1% an Ob/Gyn visit, and 75.9% reporting use of outpatient mental health services in the past year (Table 2). More than two-thirds (69.2%) received a pap smear in the past year.

Of the 329 women, 147 (44.7%) had a prior history of, or ongoing IPV (Table 1). Participants with IPV compared to those without were more likely to have had a history of childhood sexual or physical abuse (57.1% vs. 34.9%, P < 0.001), lifetime history of substance use (49.3% vs. 26.8%, P < 0.001), and prior history of homelessness (75.9% vs. 61.3%, P < 0.007). Current smoking rates did not differ between women with or without IPV (54.8% vs. 46.4%, P = 0.3). Participants with IPV were more likely to be insured compared to those without (79.5% vs. 68.3%, P < 0.03). Cardiovascular risk factors did not differ between women with or without IPV (36.3% vs. 27.4%, P = 0.09). Significantly more homeless women with IPV compared to those without reported one or more STI (40.7% vs. 25.9%, P < 0.006) or any psychiatric condition (40.4% vs. 25.6%, P < 0.005). A greater proportion of participants with IPV used emergency than PCP services in the past year (64.4% vs. 55.5%, Table 2). Participants with IPV were more likely to report seeking outpatient mental health services compared to those without (82.5% vs. 68.4%, P < 0.02).

In multivariable regression analysis, participants who experienced IPV had 1.7 greater odds (Adjusted odds ratio (AOR) 1.7, 95% CI 1.0–2.7) of having an ED visit in the past year after adjusting for significant covariates including childhood physical or sexual abuse and having any psychiatric diagnosis (Table 3). There was no association between IPV status and a PCP visit in the past year (AOR 1.5, 95% CI 0.9–2.6). Participants experiencing IPV had 1.9 greater odds of using mental health services in the past year after adjusting for covariates, although this did not attain statistical significance (AOR 1.9, 95% CI 0.9–4.1).

Discussion

Across all participants, we found that a third reported one or more diagnoses of cardiovascular risk factors, STI or any psychiatric condition. The majority of the sample was insured and most had a preferred doctor, yet less than half reported visiting their PCP in the past year. Homeless women with IPV had an increased burden of medical and psychiatric co-morbidities compared to those without, and used emergency services more than primary care. While our results suggested an association between IPV status and use of emergency services, there was no association with primary care or mental health services after adjusting for predisposing, enabling and need factors.

Similarities and differences exist between our study and those conducted among homeless women prior to 1997 [7, 9, 12, 15–17, 29]. Despite the young age of the participants in our study, a third reported one or more cardiovascular risk factors including diabetes, hypertension or obesity. Studies examining cardiovascular risk among homeless women are limited, with two previous studies reporting rates of obesity and hypertension [12, 29]. Among a sample of homeless women recruited from shelters in Massachusetts [12], 4% reported a diagnosis of hypertension and 28.2% were obese. This sample was considerably younger than ours (mean age 26.2 years vs. 36.9 years), and may explain the higher rates of hypertension seen among our study participants. A third of the participants had been diagnosed with one or more sexually transmitted infections. These rates are lower than among a sample of homeless women recruited from shelters and meal programs in Los Angeles (48.9%) [29]. A third of the participants were diagnosed with any psychiatric condition, yet the majority reported using outpatient mental health services in the past year suggesting high rates of undiagnosed mental illness in this population.

Among health care access variables, three-fourths of the homeless women reported having current health insurance. These rates are intermediate to those previously reported among homeless women (range 53.6–98.6%), perhaps reflecting differences in access to health insurance by city [7, 12, 29]. Health insurance rates in our study were higher than for a nationally representative sample of homeless adults [31]. While other studies asked about a usual source of care [17, 29], we queried participants on whether they had a preferred medical provider. A third of the participants reported not having a preferred provider, similar to prior studies where a third lacked a usual source of care [17, 29]. Rates of emergency services use was similar to previously reported estimates [12]. Despite the majority of the participants having health insurance and most having a preferred medical provider, less than half reported a primary care visit in the past year.

Because of the independent effects of homelessness and IPV, we hypothesized that homeless women with a history of IPV may have an increased burden of acute and chronic disease. Few studies have examined the causal link between IPV and cardiovascular risk, the leading hypothesis being that stress from IPV independently or through smoking increases risk for cardiovascular disease [24]. Studies among low-income women with IPV demonstrated an increased prevalence of hypertension, obesity and smoking [23, 24]. In our study, homeless women with IPV had higher rates of one or more cardiovascular risk factors when compared to those without, but this did not attain statistical significance. Given the overall young age of this population, the early presence of these risk factors underscores the need for consistent access to screening and treatment to prevent long-term complications from cardiovascular disease. The high rates of smoking among these women (54.8% compared to 19.3% in the general population and 28.9% among those living below the poverty level) [33] necessitate smoking cessation interventions that are specifically tailored to the unique needs of this population. Among homeless women with IPV, 40.7% reported having one or more STI. These rates are higher than previously reported estimates among low-income women experiencing IPV alone [20, 22], suggesting that the combination of homelessness and IPV may increase risk for STI.

The majority of homeless women with IPV reported having current health insurance and most had a preferred medical provider. Women with IPV were more likely to use health care across different types of services. These results are similar to those reported previously among low-income women with IPV [34–36]. Psychological and physical consequences of IPV contribute to the increased medical use among women experiencing IPV [37], and its effects persist years after IPV has ended [35]. The increased health care use among this group offers an opportunity for health care providers to screen for IPV and its associated long-term physical and mental health consequences.

Despite the majority of participants reporting being insured and most having a preferred medical provider, a greater proportion utilized emergency care services compared to primary care. Our results suggested that IPV status was independently associated with emergency services use, but not primary care. Adjusting for the presence of any psychiatric condition, another factor commonly associated with use of emergency services among homeless adults [38], did not change these results. While insurance is one of the determinants of a regular source of primary care [39], other barriers such as lack of transportation, child care responsibilities, or clinic waiting times may affect access to primary care [12, 17, 40]. In a recent study within a universal health insurance system in Canada, homeless women who had experienced physical assault in the past year had significant unmet need for medical care, suggesting that non-financial barriers may influence access to health care [41]. For homeless women with a history of IPV, barriers may include general mistrust of the health care system [41]. We speculate that non-financial barriers to accessing primary care may have resulted in decreased use of primary care services among homeless women with a past or current history of IPV. These results suggest a need for studies that explore the motivations behind the use of emergency care services and identifying non-financial barriers to primary care among homeless women with a history of IPV.

Women with IPV were more likely to report any psychiatric condition and the majority sought outpatient mental health services in the past year. Although women experiencing IPV had greater odds of seeking outpatient mental health services in the past year, this association did not attain statistical significance in adjusted analysis. Given the high prevalence of comorbid psychiatric, substance use disorders, and medical illnesses, a coordinated approach of primary care with mental health and substance abuse treatment is needed among this high-risk group.

Our study has limitations. Our analysis was cross-sectional, limiting our ability to make causal inferences. All our measures were by self-report, introducing a potential for recall bias. However, data from a previous study suggest that homeless adults’ accounts of health care use are accurate when compared to supplementary information from medical records [42]. Our study may not be generalizable to homeless women living in shelters in other cities where different systems of health care exist, or among women living on the streets who have worse health outcomes and barriers to access to care than those who are sheltered [16, 29]. While we obtained information on access to health insurance, having a preferred provider and past year health care use, we did not have information on whether there was an unmet need for medical care or whether other barriers to access to care might have influenced health care services use among our participants.

Few other studies have specifically focused on homeless women; our study fills this gap and offers recent data on the health, access to care and health care use among this population. We found an increased prevalence of medical and psychiatric illness and high rates of health care use among homeless women overall and particularly those with IPV. These results emphasize the need for health care providers to screen for IPV and its long-term medical and psychiatric consequences among homeless women. Despite the overall high rates of health insurance, our results suggest that more participants relied on emergency care services than primary care. Identifying barriers to primary care, beyond health insurance, may reduce reliance on emergency services and increase appropriate use of primary care and outpatient mental health services among this high-risk group.

References

Bassuk, E. L., Weinreb, L. F., Buckner, J. C., Browne, A., Salomon, A., & Bassuk, S. S. (1996). The characteristics and needs of sheltered homeless and low-income housed mothers. JAMA, 276(8), 640–646.

Bassuk, E. L., Buckner, J. C., Perloff, J. N., & Bassuk, S. S. (1998). Prevalence of mental health and substance use disorders among homeless and low-income housed mothers. American Journal of Psychiatry, 155(11), 1561–1564.

Fisher, B., Hovell, M., Hofstetter, C. R., & Hough, R. (1995). Risks associated with long-term homelessness among women: Battery, rape, and HIV infection. International Journal of Health Services, 25(2), 351–369.

Wenzel, S. L., Hambarsoomian, K., D’Amico, E. J., Ellison, M., & Tucker, J. S. (2006). Victimization and health among indigent young women in the transition to adulthood: A portrait of need. Journal of Adolescent Health, 38(5), 536–543.

Austin, E. L., Andersen, R., & Gelberg, L. (2008). Ethnic differences in the correlates of mental distress among homeless women. Women’s Health Issues, 18(1), 26–34.

The National Center on Family Homelessness. (1997). Research on homeless and low-income housed families. Available at: www.councilofcollaboratives.org/files/fact_research.pdf. Accessed 25 November 2011.

Gelberg, L., Andersen, R., Longshore, D., Leake, B., Nyamathi, A., Teruya, C., et al. (2009). Hospitalizations among homeless women: Are there ethnic and drug abuse disparities? Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research, 36(2), 212–232.

Bassuk, E. L., Dawson, R., Perloff, J., & Weinreb, L. (2001). Post-traumatic stress disorder in extremely poor women: Implications for health care clinicians. Journal of the American Medical Women’s Association, 56(2), 79–85.

Stein, J. A., Andersen, R., & Gelberg, L. (2007). Applying the Gelberg-Andersen behavioral model for vulnerable populations to health services utilization in homeless women. Journal of Health Psychology, 12(5), 791–804.

Desmond, M. (2006). ACOG recommendations for improving care of homeless women. American Family Physician, 73(9), 1655.

Weinreb, L., Goldberg, R., Lessard, D., Perloff, J., & Bassuk, E. (1999). HIV-risk practices among homeless and low-income housed mothers. Journal of Family Practice, 48(11), 859–867.

Weinreb, L., Goldberg, R., & Perloff, J. (1998). Health characteristics and medical service use patterns of sheltered homeless and low-income housed mothers. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 13(6), 389–397.

Cheung, A. M., & Hwang, S. W. (2004). Risk of death among homeless women: A cohort study and review of the literature. CMAJ, 170(8), 1243–1247.

Gelberg, L., Browner, C. H., Lejano, E., & Arangua, L. (2004). Access to women’s health care: A qualitative study of barriers perceived by homeless women. Women and Health, 40(2), 87–100.

Teruya, C., Longshore, D., Andersen, R. M., Arangua, L., Nyamathi, A., Leake, B., et al. (2010). Health and health care disparities among homeless women. Women and Health, 50(8), 719–736.

Nyamathi, A. M., Leake, B., & Gelberg, L. (2000). Sheltered versus nonsheltered homeless women differences in health, behavior, victimization, and utilization of care. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 15(8), 565–572.

Lewis, J. H., Andersen, R. M., & Gelberg, L. (2003). Health care for homeless women. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 18(11), 921–928.

Zlotnick, C., Johnson, D. M., & Kohn, R. (2006). Intimate partner violence and long-term psychosocial functioning in a national sample of American women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 21(2), 262–275.

Wilson, K. S., Silberberg, M. R., Brown, A. J., & Yaggy, S. D. (2007). Health needs and barriers to healthcare of women who have experienced intimate partner violence. Journal of Women’s Health (Larchmt), 16(10), 1485–1498.

Williams, C., Larsen, U., & McCloskey, L. A. (2010). The impact of childhood sexual abuse and intimate partner violence on sexually transmitted infections. Violence and Victims, 25(6), 787–798.

Campbell, J., Jones, A. S., Dienemann, J., et al. (2002). Intimate partner violence and physical health consequences. Archives of Internal Medicine, 162(10), 1157–1163.

Coker, A. L., Smith, P. H., Bethea, L., King, M. R., & McKeown, R. E. (2000). Physical health consequences of physical and psychological intimate partner violence. Archives of Family Medicine, 9(5), 451–457.

Cloutier, S., Martin, S. L., & Poole, C. (2002). Sexual assault among North Carolina women: Prevalence and health risk factors. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 56(4), 265–271.

Scott-Storey, K., Wuest, J., & Ford-Gilboe, M. (2009). Intimate partner violence and cardiovascular risk: Is there a link? Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65(10), 2186–2197.

Coker, A. L., Reeder, C. E., Fadden, M. K., & Smith, P. H. (2004). Physical partner violence and medicaid utilization and expenditures. Public Health Reports, 119(6), 557–567.

Paranjape, A., Heron, S., & Kaslow, N. J. (2006). Utilization of services by abused, low-income African-American women. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21(2), 189–192.

Rhodes, K. V., Kothari, C. L., Dichter, M., Cerulli, C., Wiley, J., & Marcus, S. (2011). Intimate partner violence identification and response: Time for a change in strategy. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 26(8), 894–899.

Gelberg, L., Andersen, R. M., & Leake, B. D. (2000). The behavioral model for vulnerable populations: Application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Services Research, 34(6), 1273–1302.

Lim, Y. W., Andersen, R., Leake, B., Cunningham, W., & Gelberg, L. (2002). How accessible is medical care for homeless women? Medical Care, 40(6), 510–520.

Brown, R. T., Kimes, R. V., Guzman, D., & Kushel, M. (2010). Health care access and utilization in older versus younger homeless adults. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 21(3), 1060–1070.

Baggett, T. P., O’Connell, J. J., Singer, D. E., & Rigotti, N. A. (2010). The unmet health care needs of homeless adults: A national study. American Journal of Public Health, 100(7), 1326–1333.

Kushel, M. B., Gupta, R., Gee, L., & Haas, J. S. (2006). Housing instability and food insecurity as barriers to health care among low-income Americans. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21(1), 71–77.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011). Vital signs: Current cigarette smoking among adults age ≥18 years—United States, 2005–2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 60(35), 1207–1212.

Lemon, S. C., Verhoek-Oftedahl, W., & Donnelly, E. F. (2002). Preventive healthcare use, smoking, and alcohol use among Rhode Island women experiencing intimate partner violence. Journal of Women’s Health & Gender-Based Medicine, 11(6), 555–5562.

Rivara, F. P., Anderson, M. L., Fishman, P., et al. (2007). Healthcare utilization and costs for women with a history of intimate partner violence. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 32(2), 89–96.

Kramer, A., Lorenzon, D., & Mueller, G. (2004). Prevalence of intimate partner violence and health implications for women using emergency departments and primary care clinics. Women’s Health Issues, 14(1), 19–29.

Ulrich, Y. C., Cain, K. C., Sugg, N. K., Rivara, F. P., Rubanowice, D. M., & Thompson, R. S. (2003). Medical care utilization patterns in women with diagnosed domestic violence. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 24(1), 9–15.

Padgett, D. K., & Struening, E. L. (1991). Influence of substance abuse and mental disorders on emergency room use by homeless adults. Hospital & Community Psychiatry, 42(8), 834–838.

Kushel, M. B., Vittinghoff, E., & Haas, J. S. (2001). Factors associated with the health care utilization of homeless persons. JAMA, 285(2), 200–206.

Gelberg, L., Gallagher, T. C., Andersen, R. M., & Koegel, P. (1997). Competing priorities as a barrier to medical care among homeless adults in Los Angeles. American Journal of Public Health, 87(2), 217–220.

Hwang, S. W., Ueng, J. J., Chiu, S., et al. (2011). Universal health insurance and health care access for homeless persons. American Journal of Public Health, 100(8), 1454–1461.

Gelberg, L., & Siecke, N. (1997). Accuracy of homeless adults’ self-reports. Medical Care, 35(3), 287–290.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participants for their valuable contribution to our study. We would like to thank our research assistants including Ana Alicia De La Cruz, Gladyris Concepcion, and Jessica Eichler for conducting the patient interviews. We would like to thank Dr. Margot B. Kushel for her feedback on an earlier version of the manuscript. This study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse ROI DA 091399. Dr. Vijayaraghavan is supported by a post-doctoral fellowship through the Moores Cancer Center at the University of California, San Diego.

Conflict of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vijayaraghavan, M., Tochterman, A., Hsu, E. et al. Health, Access to Health Care, and Health Care use Among Homeless Women with a History of Intimate Partner Violence. J Community Health 37, 1032–1039 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-011-9527-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-011-9527-7