Abstract

The objective of this study was to explore access to dental care for low-income communities from the perspectives of low-income people, dentists and related health and social service-providers. The case study included 60 interviews involving, low-income adults (N = 41), dentists (N = 6) and health and social service-providers (N = 13). The analysis explores perceptions of need, evidence of unmet needs, and three dimensions of access—affordability, availability and acceptability. The study describes the sometimes poor fit between private dental practice and the public oral health needs of low-income individuals. Dentists and low-income patients alike explained how the current model of private dental practice and fee-for-service payments do not work well because of patients’ concerns about the cost of dentistry, dentists’ reluctance to treat this population, and the cultural incompatibility of most private practices to the needs of low-income communities. There is a poor fit between private practice dentistry, public dental benefits and the oral health needs of low-income communities, and other responses are needed to address the multiple dimensions of access to dentistry, including community dental clinics sensitive to the special needs of low-income people.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

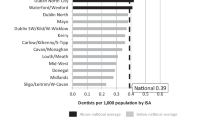

In Canada, inequities in access to healthcare and dentistry specifically for low-income and vulnerable populations are well documented [1–5]. Population data confirms oral health inequities generally [6], however, there is limited information about how to address the needs of low-income and vulnerable communities [7–10].

Access to public benefits does not automatically ensure access to health services [1, 11], which suggests that many complex issues determine perceived needs, access and utilization of dental care, and that this complexity should be considered to help develop public policy and clinical practice [12]. Currently we know little about how people on low incomes and dentists perceive one another [13].

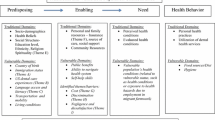

Model of Access to Care

The Behavioral Model of Health Services Use was developed and revised to explain why people, and particularly low-income communities, need and are disposed to use health services, and to identify factors that enable or inhibit access to care [14, 15]. The Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations (BMVP) uses the same framework but includes other issues, such as mental health, substance use, competing needs, and victimization [16]. Further expansion of the BMVP attempted to account for the context of access to care, along with the social, economic and public policy environments that influence access [17]. The BMVP has been used extensively to provide explanatory or predictive analysis to utilization rates [18].

Penchansky’s Model defines and measures access as a multidimensional phenomenon with five overlapping dimensions: availability; accessibility; accommodation; affordability; and acceptability [19]. It considers the fit or compatibility of the healthcare system and the people who attempt to access it, assuming that satisfaction influences utilization of services. Therefore, access is considered as a multidimensional interaction of events and circumstances [20], which is useful when focused on subjective experiences and perceptions of access rather than on utilization rates [18]. In its application, the five dimensions are sometimes modified or reduced, for example to: availability; accessibility; and acceptability [20–22] whereas others focused solely on a single issue, such as geographic accessibility [23].

Acknowledging that the models of access to care are not static but rather in constant flux, there are recommendations to work towards composite access measures using the various theoretical models [18]. A prevalent commentary is the need for access models to better incorporate the socio-political context in which people and health services interact [17, 20, 24].There is a growing awareness that models based on analyzing population databases alone do not necessarily capture the reality of life in vulnerable communities. However, information about specific communities are essential to effective health policy [24, 25]. Indeed, there has been a call to move beyond behavioral models of access focused on the individual and towards a view of access to care in its broadest sociopolitical context to incorporate conditions that perpetuate inequities such as income, food security, housing, and institutionalized oppression [26, 27].

The two possible approaches to exploring healthcare needs and utilization are “clinical” or “subjective” [28]. Population health surveys such as the Canadian Health Measures Survey [6] confirmed the prevalence of oral health disparities for economically vulnerable groups who cannot address their needs because of financial reasons. Further exploration with interviews is possible to engage people knowing about the need for and utilization of healthcare in specific communities. This paper reports on a study involving interviews with low-income people and those who provide them with healthcare to explain the interaction of social and political activities that influence access to oral healthcare for vulnerable communities.

Methods

Interviews

Sixty interviews were conducted among low-income people who sought or perceived that they needed dental care in last 2 years (N = 41), dentists (N = 6), and other healthcare or social service-providers (N = 13). Participants with low-income were recruited through postings and handbills distributed to social service and healthcare providers in the community, and by newspaper announcements. Dentists were invited by letter from a list of 36 dental offices and 50 dentists maintained by the local health authority, and six of them were interviewed. Providers of healthcare and social services were identified by the social service agencies and invited by email to participate. The interview with low-income participants began with open-ended questions allowing respondents to freely relay their experiences and perspectives. At the end of each interview participants were asked for basic demographic information along with information about how they perceived their oral health status. As interviews progressed, we purposefully sought a diversity of recruits with low incomes, social benefits, and from specific age groups, along with a reasonable balance of men and women, and of Aboriginal and non-aboriginal status. Through an iterative process of constant comparison, interviews were reviewed throughout the process to identify emerging themes and gaps in knowledge, and we modified the recruitment and interview guides accordingly for subsequent interviews.

Textual Analysis

All interviews were recorded with a digital voice recorder and transcribed verbatim. NVivo™ software was used to manage the analysis of each transcription using a thematic identification and coding [29]. We identified in each transcription the categories of information coinciding with the research questions, and searched for themes using an inductive technique that moves from the particular experiences of the participants to general themes [30]. As themes emerged, we used an iterative coding process to analyse and refine our understanding of each theme. The demographic information on each participant was collected by questionnaire and used to help explain the context of each interview.

Results

Social and Self-assessed Health Characteristics of the Participants

There was an age range of 21–62 years (mean: 45 years) among the 41 low-income participants, and a similar distribution of men and women (Table 1). Only four participants had paid-employment, and most received social assistance. Fifteen of them rated their oral health as good to excellent, whereas 23 of them experienced dental pain “sometimes” or “often” and 19 used their physician or a hospital emergency department for dental pain. Cost, fear and transport was the most frequent reason identified for not visiting a dentist.

Perceptions of Oral Healthcare Needs

The need for dental treatment was associated with references to toothache, cavities and missing or fractured teeth, typically for longstanding and multiple dental conditions. A young man (24 years) stated quite directly “as you can see, my teeth are kind of falling out in front here … just the other day a tooth fell out”. Overall, we heard that dental problems were addressed only when they became unbearable, as one woman who had a tooth extracted within the past year explained “my income just won’t cover the extras like going to the dentist; it’s just not in it. So, the only time I go is when I’m in severe pain.” Dental needs when identified by a dentist frequently went untreated even when the need seemed extensive, such as “twelve cavities, an abscess, one abscess, [a] root canal, and … an extraction” as we heard from one woman. Preventive care, such as check-ups and dental hygiene, were mentioned usually as desirable, but more as luxuries than as necessities.

The dentists were aware of people on social assistance who had difficulty getting dental treatments because of poverty, homelessness, old age or severe disability, and they were frustrated by the limited treatment covered by public dental benefits, or, as one dentist stated, “I think the biggest thing that’s missing … is they have no way to get teeth made if they have to lose all their teeth”. The allied health and social service workers reported that they frequently encountered people with chronic toothache, and visibly decayed or missing teeth, and one health provider complained how “you see” “a lot of low-income workers… [in] $8 an hour job places… [with] teeth [that] are disgusting… [because] obviously it’s low on the list of priorities.” They complained also about how they were unable to help their clients get dentures following extractions, and could do little more than ensure that they had soft food.

Impacts of Unmet Needs

Low-income participants described how missing or poor teeth disturbed their ability to eat. A woman in her late 50s with no teeth and diabetes complained somewhat defiantly how:

“my digestive system is going all out of whack all because I [cannot] chew my food … you know there’s going to be problems in the end, and then I’ll probably end up in hospital really ill and it’s going to cost them even more money.”

A soup kitchen employee observed “lots of people walking around with no teeth because, I don’t know how you access denture services through the Ministry but I know that if it was possible a lot more people would have teeth”. An edentulous man in his mid-40s with public dental benefits described how “they say they will pay for… extractions… [of my teeth, but] they’re not even there anymore, you know I’m down to about 108 lb from 210… you can’t get fat on soup.” Another woman who operates programs for women explained how they had to adapt their food program to “provide food that people who don’t have teeth can eat, … We really have to think in terms of what people can actually manage to eat if they’ve got bad teeth.”

The providers generally felt that unmet dental needs undermined their ability to assist clients in getting shelter, securing employment and improving health. A nurse explained the challenges of treating a patient who is “doubly affected by the toxins” from chronic liver disease and rampant caries from an addiction to crystal meth. The consequences of this dental neglect were, as one social service provider explained, a major loss to “their self-esteem… dignity and… ability to either hold work or find jobs, and [maintain] their health so they can keep up with their daily living activities.” A recently unemployed man with visible dental decay concurred “It’s kind of hard to get into a serving job … because you’ve got bad teeth right? … [I’ll] go for an interview and try not to smile but whose going to hire a guy that doesn’t want to smile?”

Walk-in medical clinics, physicians’ offices and hospital emergency department featured in many interviews as a source of dental care for low-income people. A dentist commented that “the medical clinic is the frontline for dental infections… some people, all they want is relief, they don’t have any hope to deal with the problem fundamentally.” As one low-income person explained, “you can get to see a doctor for free but a dentist you have to pay for.” This behaviour might well address the financial barrier to care, but concerns were raised also about the quality of dental care in emergency departments by physicians who prescribe medications rather than remove the source of pain and infection. The consequence, we heard, is that patients “get out of trouble for ten days and then they’re back again”. We heard also that emergency departments do not always welcome people who are homeless or those who use illicit drugs, as one such person explained “that’s the first thing that comes up on the computer … I couldn’t even get a painkiller.” However, another man told us how he eats “acetaminophens like candy”, and yet another complained how welfare paid for weekly prescriptions of Tylenol 3’s but refused to pay for dentistry. It was clear from several sources that the drug dealer provided much temporary relief from toothache.

Barriers to Affordability

Low-income participants along with dentists and other healthcare providers identified the cost of dentistry and the inadequacy or inaccessibility of public insurance schemes as major impediments to dental services for low-income people. A man receiving temporary social assistance complained that “[a]fter I pay my rent and my hydro and my phone, I’m left with about forty bucks a month to live on.” A woman with children working part-time explained how “I definitely need dental care but it’s a matter of finances … my income just won’t cover the extras like going to the dentist … so the only time I go is when I’m in severe pain … it’s one of those things that are in the lower list.” A nurse concurred saying “It’s just not their priority, their money has to go to other things—food and childcare and transportation—and all of those sorts of things… [and] things like glasses and teeth are luxuries”.

While dentists agreed with these financial constraints, they also raised the influence of competing values and priorities. One dentist complained about this “priorities question” with the opinion that some people who “say they can’t afford dentistry… suddenly show up in a new car”. Another complained how “they think it is too expensive because they don’t value their health enough to say ‘if I give up smoking I can afford to get my teeth fixed’”.

Low-income people who cannot afford to access a dentist usually blamed a failure in public policy. Dentists also expressed multiple frustrations with public dental plans and the difficulties of operating a dental practice when dealing with government bureaucracies because, as one explained “dentistry has to run as a business first and healthcare second … it’s not a benevolent healthcare service”. Particular concern focused on discrepancies between the fees paid by public dental benefit plans and the fee guide used by the local dental association. Another equated dental practices to most other business and explained that “the local grocery store doesn’t charge [low income customers] less for their milk or the corner store [charge less] for their cigarettes.”

Nonetheless, there is some access to public dental benefits for people with low incomes, as we heard from a young Aboriginal woman who explained that “actually my dental care has been pretty easy for me because whenever I had a problem I’d just go to a dentist and show my Status card and book an appointment”. Yet, the dentists we interviewed believed that change is required by government and not by the dental profession, because they claim that basic dental care is “basic healthcare, much like going to the physician… for some disadvantaged people, at least the basics need to be covered, not that it needs to be crowns or bridges or things along those lines, but if the fillings could be covered”.

Barriers to Availability

The availability of healthcare can be viewed from three perspectives: the geographical distribution of services; the fit between services and needs; and the willingness and resourcefulness to service the needs of a particular community. Dentists yearned for a “good balance” between demand for care and the dental practices in the region. Others acknowledged the reality of distance in a rural region, but without complaint or concern. There were concerns from low income participants in particular about ‘balance billing’ whereby dentists expected patients to pay an extra fee to balance or cover the difference between their usual professional fee and the treatment fee paid by the public benefits, and also to pay the total fee in advance of treatment. This was explained by a woman who described how she had “a really difficult time finding a dentist that actually… bills the government. All of them now want you to pay and then get reimbursed … they prefer to see patients that have the means and the money to get their teeth fixed so they’re automatically paid”. This practice was confirmed by a social service provider who remarked that “there are not many dentists [who] work at income assistance rates… so people on income assistance don’t have easy access to [dentistry].” Another participant explained further that in her town “there’s one dentist [who] agrees to do some work periodically without charging over the fee schedule that welfare will pay. But, of course, he would be inundated if he did it for everybody.”

This practice of balancing billing leads of course to outstanding debts, as we heard from an edentulous man with only one denture because, as he explained, “I still owe that denturist $300 and I need, bottom ones, right? I can’t go back to her or anything till I resolve this payment”. Similarly, we heard from a woman how “dentists don’t do payments anymore, “they want the money up front even before they look at you”.

Barriers to Acceptability

The third dimension of access is concerned with the expectations between providers and recipients of dental services. Cognitive and physical disabilities, compounded by substance use and homelessness, can be serious impediments to accessing treatment in the traditional dental practice, as we heard from a social service provider who estimated that “the majority of my clients are not able to follow through with going to an appointment … I work with mostly addicted people and people with mental health issues, so that says it all right there… [there are] major issues for dentists to try and work with that population”. We heard from dentists about difficulties managing patients in wheelchairs or long-term care facilities, or who need sedation. Moreover, according to a social service provider:

“an inability to access dental assistance and the inability to access housing go hand in hand, not exclusively, but certainly there’s a high profile of people in that category who are walking around with infected teeth and getting sick from that.”

Fear of dental treatment and associated anxiety was identified by many low-income participants as reasons for avoiding dentists, even when public dental benefits were available.

Social service workers discussed the challenges in serving clients without phones and those who are couch surfing, inadequately housed or homeless;

“The vast majority of my clients do not have a telephone … they make appointments with all good intentions but it could be 6 weeks down the road… The whole system is built on assumptions that everyone is the very organized sort of middle class lifestyle where we have phones, and day timers, and palm pilots and things like that.”

Some dentists associate missed appointments by patients on public benefits with a lack of respect, especially, as one dentist complained, when.

“they usually don’t call, they are unreliable, and so yeah, a lot of dental offices won’t treat them because they are giving it away. Basically you are doing it at cost and they don’t even show anyway so it’s completely wasted your time and your space.”

The contrasting view from low-income people is that dentists are greedy and should show more compassion, as a woman on disability benefits pleaded: “surely there’s got to be a little mercy for people that for one reason or another are on the bottom of the rung with income, you know. It would be nice if there was mercy shown”. Indeed compassion was identified by several participants as critical to enabling access for this community.

One dentist commented that health and social service-providers in town “tend to paint the dentists … like we should be guilty because we are not seeing these people.” Dentistry is seen by some as largely a business operating outside of the social safety net. A social service worker described how dental offices were unlike other agencies serving people in poverty:

“They’re not very accessible places. They’re worse than doctor’s offices in my own personal experience. They’re stuffier, and you know, everybody from receptionists to everybody’s outfits are perfect… they make a lot of money so they usually look really nice and you send in one of my guys in there—messes up the whole atmosphere.”

Others were even more critical of dentists who they believe are not interested in public health service but “go into dentistry because it is profitable”.

Overall, these findings confirm the complex barriers to accessing dental care for low-income communities. Low-income people face considerable barriers to accessing care, while dentists perceive considerable barriers to providing care within the restrictions of private practice and the limits of public dental benefits.

Discussion

This study identified the different perceptions held by low-income people, dentists and health and social service-providers about access to dentistry. It confirms some of the concerns identified by others about the cost of dentistry [31], the use of physicians and hospital services for emergency dental treatments [32–34] and reports of self-care for toothaches and other serious dental problems [35, 36]. We heard clearly that dental costs are perceived as a low priority relative to the struggle for food and shelter in low-income communities [37, 38] including those experiencing homelessness [39–41]. There was a strong belief among many of the participants, whether recipients or providers of care, that financial barriers to dentistry are due largely to a failure of public dental benefits to provide both necessary care for vulnerable communities and necessary reimbursement for dental services [10].Current barriers to access were attributed to fiscal restraint programs and successive welfare reforms [42]. There were strong opinions also that dentistry as it is usually available in private practices is incompatible with the provision of public health benefits to meet public oral healthcare needs. Moreover, dentists feel imposed upon to provide services at lower costs to some individuals and not to others, while people who are impoverished financially feel that dentists lack compassion and are motivated solely by financial gain.

For vulnerable populations, access to available services is not just a consideration of physical or geographical access, but rather the availability of dentists and other dental professionals willing and able to serve the population. Public dental benefits do not guarantee access to dental treatment because there are many dentists in private practice who refuse to accept patients with the benefits [11, 34, 43–45]. This study found rationing of dental services occurring, where dental offices may refuse certain patients or public benefits, but more often limit, or ration, access to these populations [13]. Dentists can defend rationing as they perceive the needs to far exceed their ability to provide access [12].

The research uncovered significantly differing beliefs and perceptions that could influence acceptability and ability to provide and receive care [35, 46]. The perception within the low-income community that dentists are “greedy” compounded by the feelings of dentists that people who are poor and receiving public benefits are bad and disrespectful patients is hardly a mixture for a successful health service. These feelings and perceptions are not likely to help overcome the usual fear and anxiety associated with dental treatments [36, 47, 48]. Participants typically related their fear to past experiences, but no doubt their fear was exacerbated by current anxieties and a general sense of vulnerability.

Missed appointments by low-income patients was perceived to be a significant barrier by both patients and providers. A higher rate of missed appointments among vulnerable populations has been documented in other research [13]. While some dentists perceive the missed appointment to be indicative of disrespect or not valuing one’s oral health, others acknowledge how the social determinants of health can affect access [7].

The perceptions expressed by dentists in this study reflected the real challenges inherent in providing care for economically vulnerable patients with complex needs [12]. People with active substance abuse, mental illnesses, and homelessness or abuse face individual barriers to seeking and accessing care and the service-providers also face real challenges [40, 49–52]. There is a growing awareness that dental professionals should overcome this social gap by enhancing their appreciation of the social context in which their patients live [7, 53].

Limitations

This research explored the perceptions of participants, but we did not check the perceptions against the clinical status, health records or other sources that might have helped to explain the psychological and social context of each participant. All of the low-income participants were selected purposefully to reflect a diversity of income sources, Aboriginal status, gender and age; however, the explanations we heard were probably biased by the tendency of our recruitment strategy to attract people with strong opinions based on unpleasant experiences. We recognize that generalizability is limited but the sample size was suitable for achieving our goal of exploring the complexities of access to care from both the provider and patient perspectives. Sampling did not adequately capture the experiences of employed low-income population, often referred to as “the working poor” rather the majority of the sample represents individuals who have some access to social assistance. Perhaps a telephone survey will help to explore the oral health issues of this population [54].

Conclusion

We explored the affordability, availability and acceptability of dental services encountered by low-income communities and their care-providers. Interviews with people on low-incomes, dentists and social service-providers identified clearly the incompatibility of private practice dentistry, public dental benefits and the vulnerabilities of people living in poverty. The major barriers for both dentists and low-income communities seem to be the financial demands of dentistry and the cultural conflicts that occur when people from low income communities attend private dental practices.

Affordability is probably the noticeable barrier to dentistry in these communities where financial barriers are high and dental needs compete with other more pressing everyday needs, such as food and shelter. Moreover, dentists complain that the reimbursements provided by public dental benefits do not cover their business expenses, and they are resentful of demands that they feel are not expected from other businesses or professions. Addressing access to dental care ultimately requires actions that alleviate poverty that puts people in the position of choosing between competing basic needs.

The financial barriers were attributed to health and economic policies that provide public dental benefits that are neither sufficient to meet the needs of the communities nor the resources of dentists. Additional barriers to dental services were associated with mental illnesses, physical disabilities, substance abuse, and other traumas among people living in poverty for which most dentists in private practice seem ill-equipped to manage. And, finally, there was widespread awareness among all of the participants that many private dental practices are inhospitable to people who are impoverished, disabled and ill-equipped in many ways to keep appointments and pay their debts. Solutions to the concerns raised and barriers identified were not readily available from our analyses; however, it seems reasonable that alternative models of delivering dentistry to low-income and vulnerable communities are needed beyond the model of private clinical practice. Further investigations are underway to study the potential of community-based health clinics or similar integrated care clinics to meet these dental needs.

References

Bryant, T., Leaver, C., & Dunn, J. (2009). Unmet healthcare need, gender, and health inequalities in Canada. Health Policy, 91(1), 24–32.

Grignon, M., Hurley, J., Wang, L., & Allin, S. (2010). Inequity in a market-based health system: Evidence from Canada’s dental sector. Health Policy, 98(1), 81–90.

Lawrence, H. P., & Leake, J. L. (2001). The US surgeon general’s report on oral health in America: A Canadian perspective. Journal of Canadian Dental Association, 67(10), 587.

Locker, D. (2000). Deprivation and oral health: A review. Commissioned Review, 28(3), 161–169.

Raphael, D. (2007). Poverty and policy in Canada: Implications for health and quality of life. Toronto: Canadian Scholars Press.

Health Canada. (2010). Report on the findings of the oral health component of the Canadian health measures survey 2001–2009. Ottawa: Health Canada.

Loignon, C., Haggerty, J., Fortin, M., Bedos, C., Allen, D., & Barbeau, D. (2010). Physicians’ social competence in the provision of care to persons living in poverty: Research protocol. BMC Health Services Research, 10(1), 79.

MacEntee, M. (2006). An existential model of oral health from evolving views on health, function and disability. Community Dental Health, 23(1), 5–14.

MacEntee, M. I., & Harrison, R. (2011). Dimensions of dental need and the adequacy of our response: Forum proceedings. Journal Canadian Dental Association, 77, b12.

Quiñonez, C., Figueiredo, R., Azarpazhooh, A., & Locker, D. (2010). Public preferences for seeking publicly financed dental care and professional preferences for structuring it. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology, 38(2), 152–158.

Birch, S., & Anderson, R. (2005). Financing and delivering oral healthcare: What can we learn from other countries. Journal of Canadian Dental Association, 71(4), 243.

Dharamsi, S., Pratt, D. D., & MacEntee, M. I. (2007). How dentists account for social responsibility: Economic imperatives and professional obligations. Journal of Dental Education, 71(12), 1583–1592.

Pegon‐Machat, E., Tubert‐Jeannin, S., Loignon, C., Landry, A., & Bedos, C. (2009). Dentists’ experience with low‐income patients benefiting from a public insurance program. European Journal of Oral Sciences, 117(4), 398–406.

Andersen, R. (1968). A behavioral model of families’ use of health services. Chicago: University of Chicago, Center for Health Administration Studies.

Andersen, R. M. (1995). Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36(1), 1–10.

Gelberg, L., Andersen, R. M., & Leake, B. D. (2000). The behavioral model for vulnerable populations: Application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Services Research, 34(6), 1273–1301.

Davidson, P. L., Andersen, R. M., Wyn, R., & Brown, E. R. (2004). A framework for evaluating safety-net and other community-level factors on access for low-income populations. Inquiry, 41(1), 21–38.

Karikari-Martin, P. (2011). Use of health care access models to inform the patient protection and affordable care act. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice, 11(4), 286–293.

Penchansky, R., & Thomas, J. W. (1981). The concept of access: Definition and relationship to consumer satisfaction. Medical Care, 19(2), 127–140.

McIntyre, D., Thiede, M., & Birch, S. (2009). Access as a policy-relevant concept in low-and middle-income countries. Health Economics Policy and Law, 4(02), 179–193.

Chen, J., & Hou, F. (2002). Unmet needs for healthcare. Health Reports, 13(2), 23–34.

Nelson, C. H., & Park, J. (2006). The nature and correlates of unmet healthcare needs in Ontario, Canada. Social Science and Medicine, 62(9), 2291–2300.

McCarthy, J. F., & Blow, F. C. (2004). Older patients with serious mental illness: Sensitivity to distance barriers for outpatient care. Medical Care, 42(11), 1073–1080.

Ricketts, T. C., & Goldsmith, L. J. (2005). Access in health services research: The battle of the frameworks. Nursing Outlook, 53(6), 274–280.

Newton, J. T., & Bower, E. J. (2005). The social determinants of oral health: New approaches to conceptualizing and researching complex causal networks. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology, 33(1), 25–34.

Pauly, B. M., MacKinnon, K., & Varcoe, C. (2009). Revisiting “who gets care?”: Health equity as an arena for nursing action. Advances in Nursing Science, 32(2), 118–127.

Stevens, P. E. (1992). Who gets care? Access to healthcare as an arena for nursing action. Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing Practice, 6(3), 185–200.

Allin, S., Grignon, M., & Le Grand, J. (2010). Subjective unmet need and utilization of healthcare services in Canada: What are the equity implications? Social Science and Medicine, 70(3), 465–472.

Charmaz, K. (2000). Grounded theory: Objectivist and constructivist methods. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 509–535). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Millar, W. J., & Locker, D. (1999). Dental insurance and use of dental services. Health Reports, 11(1), 55–67.

Chi, D., & Milgrom, P. (2008). The oral health of homeless adolescents and young adults and determinants of oral health: Preliminary findings. Special Care in Dentistry, 28(6), 237–242.

Cohen, L. A., Bonito, A. J., Akin, D. R., Manski, R. J., Macek, M. D., Edwards, R. R., et al. (2009). Toothache pain: Behavioral impact and self-care strategies. Special Care in Dentistry, 29(2), 85–95.

Quinonez, C., Gibson, D., Jokovic, A., & Locker, D. (2009). Emergency department visits for dental care of nontraumatic origin. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology, 37(4), 366–371.

Bedos, C., Brodeur, J., Boucheron, L., Richard, L., Benigeri, M., Olivier, M., et al. (2003). The dental care pathway of welfare recipients in quebec. Social Science and Medicine, 57(11), 2089–2099.

Bedos, C., Brodeur, J., Levine, A., Richard, L., Boucheron, L., & Mereus, W. (2005). Perception of dental illness among persons receiving public assistance in Montréal. American Journal of Public Health, 95(8), 1340–1344.

Muirhead, V., Quiñonez, C., Figueiredo, R., & Locker, D. (2009). Oral health disparities and food insecurity in working poor Canadians. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology, 37(4), 294–304.

Reid, K. W., Vittinghoff, E., & Kushel, M. B. (2008). Association between the level of housing instability, economic standing and healthcare access: A meta-regression. Journal of Healthcare for the Poor and Underserved, 19(4), 1212–1228.

Daiski, I. (2007). Perspectives of homeless people on their health and health needs priorities. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 58(3), 273–281.

De Palma, P., & Nordenram, G. (2005). The perceptions of homeless people in Stockholm concerning oral health and consequences of dental treatment: A qualitative study. Special Care in Dentistry, 25(6), 289–295.

Gelberg, L., Lin, L. S., & Rosenberg, D. J. (2008). Dental health of homeless adults. Special Care in Dentistry, 8(4), 167–172.

Williamson, D. L., Stewart, M. J., Hayward, K., Letourneau, N., Makwarimba, E., Masuda, J., et al. (2006). Low-income Canadian’s experiences with health-related services: Implications for health care reform. Health Policy, 76(1), 106–121.

Greenberg, B. J. S., Kumar, J. V., & Stevenson, H. (2008). Dental case management: Increasing access to oral healthcare for families and children with low incomes. Journal of the American Dental Association, 139(8), 1114–1121.

Patrick, D., Lee, R., Nucci, M., Grembowski, D., Jolles, C., & Milgrom, P. (2006). Reducing oral health disparities: A focus on social and cultural determinants. BMC Oral Health, 6(Suppl 1), S4.

Quiñonez, C. R., Figueiredo, R., & Locker, D. (2009). Canadian dentists’ opinions on publicly financed dental care. Journal of Public Health Dentistry, 69(2), 64–73.

Levesque, M. C., Dupere, S., Loignon, C., Levine, A., Laurin, I., Charbonneau, A., et al. (2009). Bridging the poverty gap in dental education: How can people living in poverty help us? Journal of Dental Education, 73(9), 1043–1054.

British Dental Association. (2003). Dental care for homeless people. London: British Dental Association.

Collins, J., & Freeman, R. (2007). Homeless in north and west Belfast: An oral health needs assessment. British Dental Journal, 202(12), E31.

Frankish, C. J., Hwang, S. W., & Quantz, D. (2005). Homelessness and health in canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 96, 23–29.

Hwang, S. W. (2001). Homelessness and health. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 164(2), 229.

Hwang, S. W. (2002). Is homelessness hazardous to your health? obstacles to the demonstration of a causal relationship. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 93(6), 407–410.

Moore, G., Gerdtz, M., & Manias, E. (2007). Homelessness, health status and emergency department use: An integrated review of the literature. Australasian Emergency Nursing Journal, 10(4), 178–185.

Dharamsi, S., & MacEntee, M. I. (2002). Dentistry and distributive justice. Social Science and Medicine, 55(2), 323–329.

Muirhead, V., Quinonez, C., Figueiredo, R., & Locker, D. (2009). Predictors of dental care utilization among working poor Canadians. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology, 37(3), 199–208.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR grant #DOH87104).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wallace, B.B., MacEntee, M.I. Access to Dental care for Low-Income Adults: Perceptions of Affordability, Availability and Acceptability. J Community Health 37, 32–39 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-011-9412-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-011-9412-4