Abstract

Rates of gambling and gambling-related harm fluctuate over time, influenced by availability, adaptation and demographic change, among other things. Assessing change is compromised by methodological variation. The main aim of this paper is to assess change in gambling participation and problems in adult Victorians over a 5 year period. Data are from the Victorian Gambling Study (VGS) 2008–2012 (n = 15,000) and the 2003 Victorian Longitudinal Attitudes Survey (n = 8479). An additional aim was to determine the impact of methodological differences on prevalence estimates. Despite gambling availability increasing and more activities being included participation rates declined substantially. Decreases occurred across almost all demographic groups and gambling activities. When adjustments were made for methodological differences there were no significant changes in problem, moderate risk and low risk gambling. Males and people with lower education had higher rates in both surveys. In the latter survey, two groups that experienced large participation reductions, namely young adults and metropolitan residents, emerged as additional groups with higher rates of problem and moderate-risk gambling. Further research is required to discover why overall rates of harm may have plateaued when participation continues to fall and why some groups with reduced participation experience increased harm. The findings suggest that availability and total consumption models are over-simplistic. They further suggest that to be effective prevention programmes will need to extend beyond gambling availability to include interventions directed towards individuals at risk and wider environmental determinants of vulnerability and harm. Additionally this study found that restricting administration of the problem gambling measure to subsets of gamblers generate significantly lower prevalence estimates, implying that many previous surveys under-portray gambling-related harm and that without appropriate adjustment for methodological variation findings cannot be validly compared across studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

During the past 25 years, there has been unprecedented growth in commercial gambling in many parts of the world (Abbott et al. 2014a, b; Bogart 2011). Growth has been particularly strong where urban casinos and electronic gaming machines (EGMs) were introduced. In Victoria and other Australian jurisdictions, apart from Western Australia, the widespread distribution of EGMs in pubs, clubs and casinos led to them dominating gambling markets within a few years of their introduction (Productivity Commission 1999, 2010). In Victoria from 1991 to 2001 inflation-adjusted annual per capita gambling expenditure increased almost fourfold from $400 to $1500.Footnote 1

In Australia and elsewhere very strong associations have been found between EGM availability and official expenditure at regional and local levels (Abbott 2006; Marshall 2005). However, in Victoria expenditure continued to rise for a number of years after machine numbers were capped (Productivity Commission 1999). Expenditure per EGM increased to approximately double that of other states. This appears to have been a consequence of machines being moved to locations, predominantly in lower socioeconomic neighbourhoods, where financial returns were higher.

Since 2001, although Victorian EGM numbers remained much the same and new gambling products were introduced, overall per capita gambling expenditure slowly reduced from $1500 to $1200 and decreased from 3.5 to 2.5 % of household disposable income. Similar gambling market maturation and expenditure reductions have been experienced in other parts of Australia as well as in some other jurisdictions (Productivity Commission 2010; Williams et al. 2012; Abbott et al. 2014a).

From the late-1980s a large number of general population surveys have examined self-reported gambling participation and expenditure (Abbott et al. 2014a; Vasiliadis et al. 2013). Many of these studies included measures of problem gambling and were conducted because of official and public concern about potential adverse health and social costs associated with increases in gambling availability (Abbott et al. 2014b, 2004; Williams et al. 2012). As Binde (2005) has documented, growing concern about gambling-related harm and ways to mitigate it also characterised previous historical periods of gambling deregulation and expansion. The first surveys to use current measures of problem gambling were undertaken in New Zealand and Australia during 1990 (Abbott and Volberg 1991, 1996; Dickerson et al. 1996). As in other jurisdictions these studies played a role in raising awareness of problem gambling and contributing to the establishment of services to assist problem gamblers.

It is widely believed that greater availability of gambling has led to increased gambling participation and problems. Repeat studies have now been undertaken in a number of jurisdictions, including Victoria, enabling changes in involvement and problems to be assessed over time. While methodological and other differences greatly complicate the interpretation of study findings, earlier reviews (Abbott and Volberg 1999; Shaffer et al. 1997; Wildman 1998) with varying degrees of qualification, concluded that increased availability led to greater participation and more problems. Official review bodies reached the same conclusion (Gambling Review Body 2001; National Research Council 1999; Productivity Commission 1999). Associations between participation and gambling problems have been shown to be particularly strong in the case of activities that are continuous and involve an element of skill or perceived skill such as EGMs, casino table games and sports betting (Abbott 2007; Binde 2011; Stevens and Young 2010).

Although there is support for the availability hypothesis, namely that increased gambling availability and exposure give rise to increased participation and problems, Abbott et al. (1999) argued that the nature of these relationships are complex, change over time and are influenced by a variety of individual and wider environmental factors. Abbott (2006) proposed that during exposure to new forms of gambling, particularly EGMs and other continuous activities, previously unexposed individuals, population sectors and societies are at high risk. He also proposed that over time adaptation typically occurs and problem levels reduce, even in the face of increasing exposure. Factors thought to contribute to adaptation include individual experience with new gambling forms, changes in gambling participation, increased public awareness of problem gambling, the development of informal social controls, expansion of treatment and mutual help organisations, regulatory changes and public health programmes.

More recent reviews (Abbott 2006, 2007; Abbott et al. 2004, 2014a; Shaffer et al. 2004; Vasiliadis et al. 2013) have identified a number of studies with findings inconsistent with the availability hypothesis. They include three national New Zealand surveys conducted between 1990 and 1999 (Abbott and Volberg 2000; Abbott et al. 2014a, b). These surveys, which used almost identical methodologies, found a significant reduction in gambling participation, particularly weekly participation in continuous forms of gambling including EGMs. They also found significant reductions in problem gambling prevalence. These changes occurred during a period of substantial growth in gambling availability and expenditure. Consequently the findings are consistent with the adaptation hypothesis.

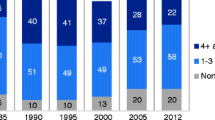

Prior to the present study, between 1992 and 2003, nine Victorian state-wide gambling participation surveys were carried out. Taken at face value, overall participation appears to have increased from around 75 % in the early 1990s, peaked at 87 and 86 % in 1996 and 1997 respectively, and then decreased subsequently within a range of 77–81 %. If this was the case the findings are in keeping with both exposure and adaptation hypotheses. However, there is some uncertainty about their validity as the survey methodologies differ in various ways. Some were presented as spare time or leisure surveys and others as gambling surveys. Some used a past 6 months and others a past year timeframe. Not all gambling activities, e.g. sweeps and raffles, were included in a number of the surveys. Methodological variations of this type are common, seriously compromising efforts to assess change in gambling participation and/or problems over time within jurisdictions and differences between jurisdictions (Abbott et al. 2014a; Sassen et al. 2011). Additionally, in the case of Australian research, it has been argued that commonly used methodological variants have produced systematic bias, downplaying the magnitude of problem gambling and related harm (Abbott and Volberg 2000, 1999).

Two studies have taken survey variations into account to varying degrees and formally examined both the availability and adaptation hypotheses with regard to problem gambling (Storer et al. 2009; Williams et al. 2012). Storer et al. (2009) conducted a meta-analysis of 34 Australian and New Zealand surveys undertaken since 1990. Adjustments were made to accommodate the different measures of problem gambling used in these studies. Adjustments were not made for other methodological differences. The analysis included the number of EGMs per capita at the time each survey was conducted, the year each survey was undertaken and the estimated problem gambling prevalence. It found that EGM density and the year that surveys were conducted both had a very strong relationship with problem gambling, together explaining 72 % of the overall variance. More specifically, prevalence increased with greater EGM density and decreased over time when density was held constant. These findings are consistent with the availability hypothesis and partially consistent with adaptation. They also indicate the major role that EGMs play with respect to problem gambling prevalence in Australia and New Zealand. This is consistent with the finding that the large majority of help-seeking problem gamblers in both countries report that EGMs are their sole or main concern (Abbott et al. 2012; Productivity Commission 2010).

Williams and Volberg (2010) conducted a study to assess the impact of two methodological variations (presentation as a gambling versus leisure study and face-to-face versus telephone interview) on problem gambling prevalence estimates. They extended this work by reviewing jurisdiction-wide studies conducted world-wide and identifying the influence of major methodological features (Williams et al. 2012). These features, in addition to how the study was presented to potential participants and how the survey was administered, included the criterion that determined when problem gambling questions were asked, the problem gambling measure and the timeframe used to assess problems. They quantified the impact of variations and developed weights to enable adjusted rates to be calculated to facilitate more valid comparisons. These weights were applied to data from 190 studies, including Victorian surveys, to assess differences between jurisdictions and change over time. When adjusted past year prevalence rates were used, considerable variation remained within Australian states, including Victoria. Overall, Australian rates were higher than those found in most other parts of the world, apart from some Asian countries and South Africa. Sufficient surveys had been completed in Australia, the United States and Canada to examine change over time. In all cases there was a clear pattern of initial increases followed by reductions, the latter commencing in the late 1990s in Canada and early 2000s in Australia in the United States.

In the case of Australia Williams et al. (2012) found, of the eight states and territories that had assessed problem gambling prevalence on more than one occasion, six had significant decreases in recent years compared to earlier years. In Victoria a 1999 adjusted estimate was significantly higher than the corresponding estimate from the first Victorian prevalence survey that was conducted in 1996. Conversely, a 2003 estimate was significantly lower than estimates from all previous surveys. However, as with the findings from the Victorian gambling participation surveys, these estimates need to be treated with caution. While the researchers made adjustments for some methodological differences they did not do so for one of the five factors they identified, namely the criterion that determines who is administered the problem gambling measure. This omission is relevant because the measure was only administered to regular (weekly) gamblers in the 2003 survey and to regular gamblers plus ‘big spenders’ in the 1999 survey. In other surveys it was administered to all adults who reported having taken part in any gambling activity during the past 6 months. A recent study has shown that restricting administration to weekly participants and/or people who report spending large amounts on gambling generates substantially lower estimates of problem and at-risk gambling (Stone et al. 2015). Thus, had the 1999 and 2003 surveys administered problem gambling measures to all past year gamblers, it is likely that their prevalence estimates would have been higher; in the case of the 1999 survey perhaps significantly higher than those from all other surveys. In the case of the 2003 estimate, apart from the 1999 survey, it may no longer have differed significantly from the others.

In addition to variation in gambling participation and problems across jurisdictions and over time, there is also diversity within populations. In Australia gambling participation has become widespread across most demographic groups. However, regular participation, particularly in continuous forms, is more common among males, older adults and people with lower levels of education and income (Productivity Commission 1999, 2010). Problem gambling and other gambling-related harm generally follows, and presumably widens, lines of existing social and health inequality. Male gender, younger age, low income and single marital status frequently feature as risk factors. In some studies large city residence, low occupational status, less formal education and minority ethnic status also feature (Abbott et al. 2004; Williams et al. 2012). In some jurisdictions it appears that risk profiles have changed over time. In New Zealand, for example, gender, age and socioeconomic differences diminished somewhat from 1990 to 1999 (Abbott and Volberg 1991, 2000). Similar changes, particularly with regard to gender, have been found in parts of Australia (Abbott 2006; Productivity Commission 1999, 2010) and North America (Volberg 2004) and were associated with the widespread distribution of EGMs. However, in other jurisdictions gender differences have persisted or increased (Abbott et al. 2013).

We report selected results from the first wave of the Victorian Gambling Study: A longitudinal study of gambling and health in Victoria 2008–2012 (Billi et al. 2014a). This cross-sectional CATI survey of 15,000 adults was primarily undertaken to assess the prevalence of gambling and problem gambling in the adult Victorian population (Hare 2009). It was also the baseline study for a 4 year prospective research programme. Overall programme objectives additionally included estimating the incidence of problem gambling, investigating pathways into and out of gambling risk states (including problem gambling), and understanding risks and vulnerabilities related to gambling behaviour, health and problem gambling. This is the largest epidemiological gambling research project undertaken in Australia and is one of only a few large-scale jurisdiction-wide prospective studies conducted internationally. Similar studies are ongoing in Sweden (Abbott et al. 2013) and New Zealand (Abbott et al. 2014a, b). These three studies are designed to facilitate comparison across jurisdictions including, potentially, data linkage and analysis.

This paper discusses the most recent Victorian adult gambling participation and problem gambling prevalence estimates. It compares these findings with those from a state-wide survey conducted 5 years earlier. This paper also examines the impact on prevalence when adjustments are made for methodological differences between these studies, including the omission of some gambling activities and the administration of the problem gambling measure to a subset of gamblers.

Materials and Methods

2003 Victorian Longitudinal Community Attitudes Survey (The Centre for Gambling Research: Australian National University 2004)

The 2003 Victorian Longitudinal Community Attitudes Survey sampled 8479 adults (over 18 years) from households randomly selected from Victorian residential telephone numbers in the Electronic White Pages (EWP). The population was stratified across metropolitan/non-metropolitan areas. Weightings were applied to correct the sample to the known population while taking into account the stratified sampling procedures. The survey response rate was 35 % using the method recommended by Williams and Volberg (2010). The survey was introduced as important social research about people’s attitudes to gambling.

The questionnaire was administered using computer aided telephone interviewing (CATI) and had three stages: an initial screen, a core survey and a problem gambling survey. The initial screen was presented to all 8479 respondents to assess their gambling status. It asked about participation in gambling activities and frequency over the last 12 months. The activities listed included: gambling on electronic gaming machines, betting on horse or greyhound races at racetrack or an off-course venue, purchase of instant scratch tickets, lotto or other lottery games, Keno, table games, sporting events betting, casino games on the internet for money, and other (excluding raffles and sweeps). Regular gamblers were defined as gambling at least weekly (52 times over past year) in any of the listed gambling activities except lottery games or instant scratch tickets. Non regular gamblers were defined as gambling less than once a week in only one activity, or an overall frequency of gambling was less than 52 times a year.

The core survey was delivered to a 1758 subset of respondents consisting of random samples of the most populous groups (1 in 3 non-gamblers and 1 in 6 non regular gamblers) and all regular gamblers. The core survey asked questions on socio-demographics, perceptions about gambling issues, effects of gambling and policy issues. Gamblers were asked further questions about gambling activities and patterns, reasons for gambling and opinions about gambling.

Regular gamblers were asked questions on help seeking and randomly allocated to receive one of three problem gambling screens: the Revised South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGSR5+, n = 143) (Abbott and Volberg 1996, 2006; Lesieur and Blume 1987), the Canadian Problem Gambling Index (CPGI, n = 141) (Ferris and Wynne 2001) and the Victorian Gambling Screen (VGS, n = 149) (Tovim et al. 2001). The assumption was that non regular gamblers and people who participated in lotteries and instant lotteries (scratch tickets) only were non problem gamblers.

The choice of problem gambling measure was based on the research strategy to maintain continuity with previous Victorian surveys that had used the SOGSR, while enabling comparative testing of the VGS and CPGI with a view to the possible progression to one or both of these new measures in future studies. At that time Queensland had recently completed a state-wide prevalence survey using the Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI), a set of nine items from the CPGI (The Centre for Gambling Research 2004).

In the Queensland study, on the advice of the Office of the Government Statistician, a modification to the original PGSI response format was used. This change was made because a pilot study found that Queenslanders did not differentiate well between the “most of the time and “almost always” options on the four point scale (personal communication, Office of Economic and Statistical Research, Queensland Treasury 2015). The modified response scale consisted of five options (never, rarely, sometimes, often, always) rather than the original four (never, sometimes, most of the time, almost always). Responses of ‘rarely’ and ‘sometimes were combined and given a score of 1. This enabled the rage of scores to range from 0 to 27 as in the original PGSI. Cut-points for the total PGSI score also remained as they were when the four item scale was used, namely 0, non-problem gamblers; 1–2, low-risk gamblers; 3–7, moderate-risk gamblers; and 8 and above, problem gamblers (Queensland Treasury 2001).

The validity and psychometric properties of the three problem gambling measures were examined as part of the 2003 Victorian study. It was concluded that the modified PGSI outperformed the SOGSR and VGS on most dimensions considered, namely content validity, response distribution and variance, one-dimensionality, internal consistency, item distributions, and construct and classification validity (The Centre for Gambling Research 2004b).

New variables were derived for the comparative analysis with the 2008 study. Each analysis used the maximum number of participants possible. So participation rates and some socio-demographics were estimated from all respondents (n = 8479) from the initial screen. Participation rates by additional socio-demographic breakdown were estimated from the subset (n = 1758) of participants who answered the core questionnaire. PGSI risk segment estimations and socio-demographic analysis were conducted on a further subset of participants (n = 1466) who answered the core questionnaire less the regular gamblers who were screened by the SOGSR or the VGS as their PGSI status was unknown. The sample was re-weighted according to the selective sampling at each stage of the survey.

The Victorian Gambling Study (VGS) 2008–2012 (Billi et al. 2014)

The VGS baseline epidemiological wave used random digit dialling to survey 15,000 Victorians, 18 years and older, in 2008 (Hare 2009). The sample was stratified by the eight state government regions and by high, medium and low electronic gaming machine (EGM) expenditure in local government areas within these regions. High EGM expenditure areas were oversampled in the ratio of high 70 %, medium 20 % and low 10 %. Weights were applied to correct the sample to the known population while taking account of the stratified sampling procedure. The survey was introduced to potential participants as ‘The Victorian Government is conducting a study on an important health and well-being issue to Victorian communities.’ The survey response rate of 52 % was calculated in the same way that it was in the 2003 survey.

Using CATI the questionnaire collected information on participants’ demographics, gambling participation and frequency over the previous 12 months. Activities included informal private betting (e.g. playing cards at home for money), gambling on electronic gaming machines (EGM), betting on table games (e.g. blackjack, roulette, poker), horse or harness racing or greyhounds betting (racing), sports and event betting, Lotto, Powerball or the Pools, Keno, scratch tickets, bingo and raffles, sweeps and other competitions, event wagering (e.g. wagering on the outcomes of TV shows), participation in SMS or phone-in competitions and participation in speculative stock investments (such as day-trading in stocks and shares).

Anyone who gambled on at least one of these activities in the past year completed the Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI) (Ferris and Wynne 2001). As in the 2003 survey, the Queensland modification of the item response scale was chosen in preference to the original 4-point scale. As mentioned this PGSI variant had been validated against the SOGSR and VGS as part of the 2003 Victorian study. Since 2003 it has been used in a number general population surveys in other Australian jurisdictions. The major reason for using it in the 2008 study was the high priority given to comparing the results with findings from the earlier Victorian study and recent studies elsewhere in Australia.

All problem, moderate- and low-risk gamblers, and one in three non-problem gamblers were then asked further questions on gambling behaviours, demographics, physical and mental health, environmental and social factors and help seeking behaviours. Details of the method are published in reports of the VGS study (Hare 2009; Billi et al. 2014b).

Analysis

Analyses were conducted using the survey module of STATA SE 12. All data were weighted. Proportions and percentages with confidence intervals (95 %) were estimated for all identified populations. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression were used to investigate the strength of association between problem gambling and the socio-demographics factors of interest. Multivariate models were built stepwise starting with the strongest associations.

Results

Gambling Participation

Participation rates in any gambling activity and individual gambling activities were analysed and results compared between the 2008 and 2003 surveys (Table 1). In 2008 almost three quarters (73 %) of the Victorian adult (18 years and older) population was estimated to have gambled at least once over the previous 12 months. Almost a quarter (23 %) of the population gambled weekly or more frequently and 41 % gambled monthly or more. A third (32 %) gambled less than once a month. A quarter (25 %) of the population gambled on one activity only. These rates are significantly lower than the participation rates in 2003. The size of these reductions increased as frequency of gambling increased; last 12 months (reduced by 6 %), monthly (by 15 %) or weekly (by 39 %). These reductions occurred in spite of more gambling activities being collected in the 2008 survey.

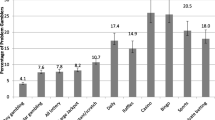

In 2008 the most common activities were Lotto, Powerball or the Pools (48 %), tickets in raffles and sweeps (43 %), EGMs (21 %), racing (16 %) and scratch tickets (15 %). In 2003 the most common forms of gambling were similar; Lotto (58 %), EGMs (33 %), racing (28 %) and scratch tickets (25 %). For all of these activities reductions in gambling at all frequencies were seen between 2003 and 2008. Reductions were also found for most other activities that could be compared. Only weekly Keno players showed a significant increase from 0.17 to 0.41 % between the two surveys.

Past year percentage reductions in order of size of effect were Keno (by 54 %), horse and greyhound racing (by 42 %), scratch tickets (by 39 %), table games (by 37 %), EGMs (by 36 %), sports betting (by 28 %) and Lotto (by 18 %). Similar reductions were seen in the proportion of the population that gambled at least monthly on an activity. These reductions achieved significance for table games (by 59 %), scratch tickets (by 54 %), EGMs (by 42 %), horse and greyhound racing (by 36 %) and Lotto (by 26 %). For weekly gamblers on an activity, reductions achieved significance for scratch tickets (by 60 %), EGMs (by 39 %), Lotto (by 30 %) and horse and greyhound racing (by 27 %).

Comparison of the 2003 and 2008 survey results in Table 2 shows participation rates at different frequencies by gender, age group, area of residence, English language, education and household type. There is considerable demographic variation within each survey and also in the extent to which participation changed over time.

From 2003 to 2008, across almost all demographic groups, there was a reduction in participation. This was especially so for weekly and monthly participation. Many of these reductions are statistically significant. None of the apparent increases are significant. In the case of weekly participation, particularly large reductions are evident for young adults (by 53 %), people with a university degree (by 37 %) and those whose main language is not English (by 44 %).

In both surveys differences between demographic groups were less evident for past year participation. In 2003 there were no significant differences at this level of participation apart from adults aged 25–64 years having higher rates than older adults and those with the lowest level of education having higher rates than adults with degrees. In 2008 there was more variation. Both young adults and adults aged 75 years and older had lower participation than other age groups. Participation also varied significantly by location (higher in rural areas), education (higher in lower educated groups; lowest in the group with degrees) and language spoken at home (higher when speak English). More substantial differences were found in regular (weekly and monthly) participation.

In both 2003 and 2008, weekly and monthly participation was more prevalent in males, people aged 45 and over, rural/regional area of residence, education lower than University graduate, and English the main language (2003)/speaks English at home (2008). Households made up of a single person with children had the highest participation rates in 2003 whereas variation in participation rates was not significantly different across household types in 2008.

Table 3 provides participation rates for individual gambling activities by gender, age and residence. Similar to the overall participation rate, rates decreased between 2003 and 2008 in most activities across these demographic groups. In 2008 males reported significantly higher participation than females in table games, racing and sports betting. This was also the case in 2003. In 2008, but not in 2003, males participated more in EGMs. In 2008 there was no gender difference for Keno whereas in 2003 males took part somewhat more often. In 2008 males more often bet informally and made speculative investments. These activities were not included in the 2003 survey. In both surveys there was no gender difference in Lotto participation. In contrast, in both surveys, females more often purchased scratch tickets. In 2008 females also more often participated in phone competitions and raffles. These activities were not included in the 2003 survey. There were some gender differences in the extent to which participation reduced between surveys. Greater reductions were evident for females in the case of table games (females by 51 %; males by 33 %), EGMs (42; 29 %), racing (53; 33 %) and sports betting (35; 26 %). Higher female reductions in these activities further amplified gender participation differences in 2008.

Most of the gambling activities preferred by males also had higher participation rates in younger age groups. Compared to people aged 45–65 years participation was significantly higher in 18–24 year olds for table games and sports betting in both surveys. In 2003, but not in 2008, this young adult group also had significantly higher participation in racing, EGMs and scratch tickets. In 2008 it was higher for private betting. Participants were not asked about this activity in 2003. Relative to adults aged 45–65, the next youngest group (25–44 years) also had significantly higher rates for table games and sports betting in both 2003 and 2008. This group also had higher racing participation in both surveys and higher private betting participation in 2008. In contrast to young adults, people aged 25–44 had had lower EGM participation in both surveys. In both 2003 and 2008 adults aged 65 and over had lower rates of participation in table games, racing and sports betting than did people in all other age categories.

Gambling activities preferred by females also varied by age. Scratch ticket participation, in 2003, was significantly higher for young adults than it was for adults in other age categories. There was no age difference, however, in the subsequent survey; bingo participation was significantly higher for people aged 65 and over. Competitions by phone were significantly more often played by people aged 25–44 and significantly less by those 65 and over. People aged 45–64 had the highest level of participation in raffles and sweeps, significantly higher than those aged 18–24, 25–44 and 75+. It will be recalled that only 2008 survey participants were asked about their involvement in bingo, phone competitions and raffles.

With regard to age, young adults changed the most from 2003 to 2008. There were statistically significant reductions in participation in all activities assessed in both surveys. These reductions were substantial, ranging from 40 to 74 %. While rarely as large, significant reductions were also apparent for the older age groups. EGM, racing and scratch participation decreased at all ages. Table games decreased for adults aged 25–44 but not those aged 45 and older. Sports betting did not decrease in any group other than the youngest. Keno and Lotto reduced in all groups apart from the oldest.

In both 2003 and 2008 metropolitan residents reported higher levels of table game participation than rural participants did. In contrast, again in both surveys, more rural participants favoured scratch tickets. In 2008, but not 2003, significantly more rural residents participated in Keno and Lotto. In the 2008 survey more rural participants also took part in EGMs, bingo and raffles. Metropolitan residents decreased their gambling in each activity more than rural residents did. Metropolitan decreases ranged between 20 and 57 %; rural between 12 and 38 %.

Problem Gambling

Prevalence

The estimated prevalence of past year problem gambling in the Victorian adult population in 2008 was (0.70 %; 95 % CI 0.55 %, 0.90 %) based on a PGSI score of 8 and higher. An additional 2.36 % (2.06, 2.70 %) scored between 3 and 8 on the PGSI and were classified as moderate risk gamblers. Low-risk gamblers were estimated to be 5.70 % (5.23, 6.21 %) of the population and non-problem gamblers 64.31 % (63.30, 65.31 %). These proportions correspond to over 28,000 Victorians being problem gamblers, almost 95,000 being moderate risk gamblers, almost 229,000 being low risk gamblers and over 2.5 million non-problem gamblers. Using the 2003 data from those who were screened with the PGSI, the corresponding prevalence estimates were problem gamblers, 0.94 % (0.58, 1.51 %), moderate risk gamblers, 0.88 % (0.57, 1.37 %), low risk gamblers, 1.92 % (1.39, 5.65 %) and non-problem gamblers, 70.76 % (68.36, 73.06 %). The number of gamblers in the 2003 survey was small as only a third of regular gamblers were screened using the PGSI. This results in broader confidence intervals.

These results suggest no significant change in the prevalence of problem gambling, an increase in moderate and perhaps in low risk gambling and a decrease in non-problem gambling. However, in 2003, only regular gamblers were screened for problem gambling and non-regular gamblers were assumed to be non-problem gamblers. Regular gamblers were defined as weekly gamblers on any activity except lottery games and scratch tickets. Stone et al. (2015) showed, using data from the 2008 survey, that if the PGSI had been administered only to weekly gamblers then the 0.70 % problem gambler estimate would have fallen to 0.54 %. Greater reductions were found for moderate risk (2.33–1.30 %) and low risk (5.60–2.72 %) gamblers. With this adjustment it is evident that there is no significant change from 2003 to 2008 for problem, moderate-risk and low-risk gamblers. However, there are additional methodological differences between these two studies that also require consideration. Specifically, in the 2003 study some gambling activities were not included, and those who participated in these excluded activities, unless they also took part in activities that were included, were classified as non-problem gamblers. Additionally, the 2003 survey was presented to potential participants as a gambling study, whereas the 2008 survey was presented as a health and wellbeing study.

In the introduction mention was made of Williams et al. (2012) method of weighting major methodological differences to produce standardised rates of problem (equivalent to PGSI 8+) and ‘high risk’ gambling (equivalent to PGSI 3+). The weights are a factor of 2.17 to convert from PGSI8+ or 0.58 to convert from PGSI3+ to the standardised problem and pathological gambling measure; a factor of 1.44 to convert results from a telephone survey a face-to-face survey; and a factor of 0.53 to adjust for a survey being described as a gambling survey rather than a non-specific leisure or health survey. As mentioned, while they noted that limiting the administration of problem gambling measures to a subset of gamblers would affect prevalence estimates, they did not provide a weight to correct for this variation. Following from Stone et al.’s (2015) examination of the impact of limiting the measure to regular gamblers, a factor of 1.30 is proposed to convert PGSI8+ and 1.65 to convert PGSI3+ from a weekly threshold to the threshold of all people who took part in any gambling activity during the past 12 months. Simulations were also run to take account of the 2003 survey excluding regular Lotto or scratch ticket participants. From these simulations we propose factors of 1.89 and 2.83 to convert PGSI8+ and PGSI3+ respectively, when weekly and reduced gambling activities are used to determine who is assessed for problem gambling.

The foregoing results are shown in Table 4. The fourth column provides standardised prevalence estimates by making the adjustments recommended by Williams et al. (2012). This includes adjustment for one of the methodological differences between the two Victorian studies, namely how the surveys were presented to potential participants. The fifth column incorporates the adjustment to take account of differences that arise from administering the PGSI to weekly versus all past year gamblers. The sixth column adds, in addition to all the proceeding adjustments, an adjustment for excluding Lotto and scratch ticket participants. When the two latter adjustments are made, the 2003 PGSI8+ and PGSI3+ based standardised prevalence estimates are respectively around two and three times higher than they are when using the Williams et al. (2012) adjustments on their own. With all of these adjustments made the estimates from the two surveys are virtually identical.

Sociodemographic Differences and Risk Factors

The numbers of problem gamblers are small, particularly in the 2003 survey. To obtain robust results for subgroup analyses, problem and moderate risk gamblers are combined into a ‘high-risk’ group. Table 5 shows the prevalence estimates for problem gamblers and high risk gamblers by selected sociodemographic characteristics for both 2003 and 2008. In 2008, the prevalence of problem gambling was significantly higher among males than females and in the 25–44 and 45–64 year age groups compared with the 65–74 year age group. In 2003 the prevalence was significantly higher in those whose education was up to year ten compared to those with a university education. There were no significant gender or age differences.

The 2008 prevalence estimates of the high risk group were significantly higher in males than females, in the 18–24 age group compared with the 65–74 years and 75 years and older age group, and tended to decrease with increasing education. In 2003, high-risk prevalence also tended to decrease with increasing education. However, in contrast to the 2008 finding, it tended to increase with increasing age.

Major apparent changes between 2003 and 2008 are an increase in high risk group prevalence estimates for the 18–24 age group, metropolitan residence and living in households consisting of couples with children. However, adjustments are not made for the methodological differences between the two surveys. When these adjustments are made, the differences are not significant.

The results of the univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses of the relationship between high-risk gambling and sociodemographics conducted 2003 and 2008 data are presented in Table 6. Univariate analysis of the 2008 data showed that high risk gambling is significantly associated with gender, age and education and approaching significance for whether a language other than English is spoken at home. These variables and place of residence are sufficient for inclusion in the final model. Household type did not show an association with high-risk gambling. When these variables were incorporated in a stepwise fashion into the multivariate logistic regression, the odds ratio for high risk gambling was significantly higher for males compared to females and for 18–24 year olds compared with 45–64 year olds. The odds ratio for high risk gambling was significantly lower for those with a university degree, TAFE or technical qualification, or year 12 compared to those who achieved year 10 or lower education, and 65–74 year olds and 75 years and older compared with 45–64 year olds. Approaching significance, the odds ratio was higher for those who spoke a language other than English at home compared with those who did not, and was lower for those who lived in rural/regional areas compared with those who lived in metropolitan areas of Victoria.

In 2003, at the univariate level, high risk gambling was significantly associated with educational attainment and approaching significance for gender, Australian born and household type. When these variables were incorporated in a stepwise fashion into the multiple logistic regression, the odds ratio for high risk gambling was significantly higher for males compared to females, not being Australian born compared with Australian born, single without children compared with couples with children. The odds ratio for high risk gambling was significantly lower for those with a university degree, compared to those who achieved year 10 or lower education. Approaching significance, the odds ratio was lower for those with a TAFE/technical qualification compared with those who achieved year 10 or lower education.

Gambling type and frequency was examined in relation to problem and high risk gambling. The results are shown in Table 7. They show that problem and high risk gambling is associated with increasing frequency of gambling and certain types of gambling. Generally, as the frequency of gambling on any activity or on any specific activity increased, the prevalence of problem and high risk gambling increased in both surveys. When the type of gambling activity was considered, the estimated prevalence of problem gambling for 2008 was significantly higher for those gambling on EGMs or table games at all frequencies, Keno (any, monthly), and sports betting or bingo (any) than gamblers overall. For high risk gamblers, prevalence was higher for gamblers on EGM, table games, racing, sports betting and Keno (all frequencies) and informal private betting, scratch tickets and bingo (any, monthly) compared with gamblers overall. The estimated prevalence of problem gambling for 2003 was significantly higher for monthly and weekly EGM gamblers than gamblers overall. The estimated prevalence of high risk gamblers was significantly higher for gamblers on EGM and sports betting at all frequencies, table games and racing (monthly, weekly) and Keno (any) compared with gamblers overall.

Discussion

A particularly notable finding is the substantial reduction in overall gambling participation between the two surveys, especially in regular (monthly and weekly) participation. These reductions apply to all of the more popular activities and most other gambling activities at all participation frequencies (past 12 months, monthly and weekly). This includes regular EGM participation and betting on horse and dog races. In the case of casino table games monthly but not weekly participation decreased. It is also of note that reduced overall participation was found across almost all demographic groups. It is possible that methodological differences between the two surveys influenced the findings. Given that more gambling activities were included in the 2008 survey it could be expected that the reductions observed in overall participation are conservative. On the other hand, it appears that surveys presented as health rather than gambling surveys, especially if response rates are low, give rise to somewhat lower problem gambling estimates (Williams et al. 2012). The extent of this and other methodological differences on participation rather than problem gambling estimates is not known. It would be timely to give this matter greater attention along with more rigorous consideration of how gambling participation is measured in general population and other settings. To date, attention has largely focussed on the assessment of problem and harmful gambling. Assessment of participation including self-reported expenditure is of interest in its own right and is also important in advancing understanding of relationships between gambling availability (exposure), gambling participation and health and wider social harm associated with participation.

While some uncertainty remains about the possible impact of methodological differences on the participation results, they are consistent with overall gambling participation reductions that have been found in some other Australian jurisdictions during the past decade (Productivity Commission 2010; Department of Justice and Attorney General 2011) as well as in New Zealand (Abbott et al. 2014a), Sweden (Abbott et al. 2013), the UK (Wardle et al. 2010) and elsewhere (Williams et al. 2012). Some of these studies have used similar or identical methodologies over time.

In Victoria, while most age groups had significant reductions in gambling participation, the reduction for young adults was particularly marked. In the case of weekly participation it more than halved from 2003 to 2008, to around a fifth the rate of people aged 45 and over. While all age groups had significant participation reductions in EGMs, track betting and scratch tickets from 2003 to 2008, they were particularly large for young adults. The Swedish and New Zealand national studies also found much larger reductions among young adults than older age groups (Abbott et al. 2013, 2014a).

In both Victorian surveys, while there was no gender difference with respect to past year gambling participation overall, males more often gambled on a regular basis and they more often participated in table games and betting on track racing and sports events. Females, on the other hand, more often purchased scratch and raffle tickets, played bingo and took part in phone competitions. Gender differences of this type have been observed in a number of previous studies in Australia, North America and Europe. There was no gender difference in Lotto participation or, in 2003, in EGM participation. However, in 2008 male EGM participation was somewhat higher. Relative to men, women had substantially greater reductions in table games participation and betting on track and sports events. These reductions further increased gender differences and suggest that some traditional gender preferences are resistant to change and are increasing in Victoria. EGM participation also decreased more for women than for men. There is reason to believe that female EGM participation has played a significant role in the increased ‘feminisation’ of problem gambling in some parts of the world including Australia (Abbott 2006; Productivity Commission 2010).

Adults living in metropolitan areas also reduced their gambling activity substantially more than was the case for rural residents. This was associated with the emergence of urban–rural participation differences in the latter survey, including higher rural EGM involvement. Casino table games participation, however, remained higher in metropolitan areas. This is not surprising given that the casino is located in a metropolitan location whereas other activities are widely distributed. Large reductions were also found for people whose main language was not English/spoke a language other than English at home and for University graduates.

The reductions in participation, including reduced frequent involvement in a number of high risk forms of gambling, took place in Victoria and in some other jurisdictions during times when gambling availability was increasing, including existing forms and the introduction of new forms and ways of accessing them. During these periods official gambling expenditure either decreased, as in Victoria and New Zealand, or plateaued, as in Sweden. These findings are consistent with the adaptation hypothesis, namely that despite increased availability, gambling participation can decrease as novelty wears off and people become more aware of the harm and social costs associated with gambling. The substantially larger reductions for some groups including young adults, women, university graduates and metropolitan residents suggest that adaptation has occurred more rapidly in these groups than in others. As mentioned, a number of recent studies have found this for young adults. Further research is required in other jurisdictions to determine whether these groups are adapting more rapidly elsewhere.

The present study, like many previous studies, found that regular casino table games and EGM participation are particularly strongly associated with problem and moderate-risk gambling. In 2008, an estimated 62 % of weekly table games participants and 35 % of EGM participants were in the high risk (combined problem and moderate-risk categories). High prevalence rates were also found for people who regularly bet on racing and sports events and participated in Keno. People who made informal private bets, took part in gambling competitions via phone and played bingo or scratch tickets also had somewhat elevated rates relative to people who regularly purchased Lotto or raffle tickets. This rank ordering of activities on the basis of problem and high risk gambling is almost identical to the relative harmfulness of gambling forms identified by Binde (2011) from an examination of results from surveys conducted predominantly in Europe.

In addition to reduced gambling participation, the adaptation hypothesis predicts that problem gambling and other gambling-related harms will reduce over time and that this, in part, is a consequence of a reduction in participation in EGMs and other activities that have a strong relationship with problem gambling (Abbott 2006). Other factors are also thought to be involved including increased ‘host’ resistance, where various protective attributes enable people to reduce the likelihood that participation will lead to loss of control and problematic gambling. This has been little studied and is probably best assessed by case control studies, including nested studies within large longitudinal surveys. The focus would be on identifying factors that distinguish regular participants in continuous forms of gambling who do not develop problems from those who do. Intervention studies could also be designed drawing on findings from case control studies and other research.

In Victoria, although the participation findings are consistent with adaptation, this does not appear to be so with respect to problem and moderate-risk gambling. When adjustments are made for methodological differences there is no evidence of a reduction in prevalence rates between surveys. While some uncertainty remains around the validity of the Victorian estimates given the number of adjustments that were made to them, the findings are similar to those from Sweden and New Zealand. In these countries there were also widespread reductions in gambling participation, including regular participation in some high risk activities that were not accompanied by reductions in current problem gambling. Caution is required when inferring temporal change from just two surveys, even when they use very similar or identical methodologies. Nevertheless, it appears likely that in all three jurisdictions, while gambling participation decreased, problem and at-risk gambling plateaued. Further research is required to verify this and identify factors that inhibit and facilitate further reductions in gambling-related harm.

The Victorian population is diverse and it is expected that some sectors will be more robust and others prone to develop gambling-related problems. Differential rates of exposure to and participation in EGMs and other forms of continuous gambling is one of the reasons why some groups are thought to be at higher risk. As mentioned in the introduction males, young adults, people with low incomes and single people are frequently found to have higher prevalence rates. Large city residence, low occupational status, lower education and minority group status have somewhat less consistently been associated with elevated risk. Consistent with international literature, in both 2003 and 2008, the multivariate analyses identified males and people with low levels of formal education as being at high risk. In 2003 migrants were also in this category. In 2008, people who spoke a language other than English at home had a higher odds ratio but it did not quite reach statistical significance. Living in metropolitan areas was also of marginal significance. Age was not a risk factor in 2003 whereas in 2008 young adults, particularly young males, were at significantly higher risk than adults aged 45–64 and adults aged 65 an older were at significantly lower risk. People resident in rural areas also were at greater risk in 2008, but not in 2003.

It is of interest that the relative increase in young adult prevalence occurred despite a very large decrease in weekly gambling participation in this age group, including participation in high risk gambling activities. The same result was obtained in Sweden (Abbott et al. 2013). The availability hypothesis predicts a decrease in problematic gambling in this situation. It is important to understand why problems increased in this group when they reduced or plateaued in most other sectors of the population. This includes understanding why they are increasing when young people are reducing frequent gambling participation. Rates may also have relatively increased somewhat for people living in metropolitan areas and adults living in households with children. As with young adults, metropolitan residents also evidenced large participation reductions from 2003 to 2008. Given the adverse impacts that parental problem gambling has on children this finding also requires further examination.

While young adults had substantially lower rates of regular gambling participation in 2008, they continued to have relatively high participation in EGMs and some other continuous gambling activities. Further research is required to assess gambling participation among adolescents and young adults. The availability hypothesis (Abbott 2006) predicts that population sectors recently exposed to gambling, particularly continuous forms, are at elevated risk for the development of gambling problems. In Australia and many other countries people cannot readily access EGMs and most other forms of continuous gambling until they are 18. It is not surprising that this is a time when they are at elevated risk for gambling problems.

It has also been proposed that some migrant groups, especially during their early years of relocation, will be vulnerable (Abbott and Volberg 2000; Abbott et al. 2014b). This has been found in a number of New Zealand studies where Pacific Island people have particularly high rates of problem gambling. Some of these studies have also found that migrants more generally, probably in large part due to many coming from parts of Asia and other countries where access to continuous forms of gambling is limited, have high rates (Abbott et al. 2014b). These groups, like young adults, have ‘bimodal’ patterns of gambling involvement. High proportions do not gamble at all but the relatively small proportion that gambles frequently does so with high intensity and incudes a disproportionately large number of problem and at-risk gamblers. In the Victorian surveys migrants (in 2003) and people who spoke a language other than English at home (in 2008), had significantly or marginally higher risk of being high risk gamblers.

In Victoria and some other Australian jurisdictions, as well as in New Zealand and Sweden, surveys indicate that during the past 10–15 years there have been substantial increases in the proportion of adults that do not gamble and substantial reductions in the proportion that gambles regularly (Abbott et al. 2014a, b). These changes have occurred across many but not all gambling activities including EGMs and some other continuous forms. These changes and the corresponding reduction in or stabilisation of problem gambling rates are consistent with the adaptation hypothesis. In the case of Victoria and other jurisdictions where participation has continued to drop but the prevalence of gambling problems appears to have plateaued the question arises as to why this has occurred. In addressing this question it is important to take a prospective perspective and to include information from longitudinal and other studies as well as from repeat cross sectional participation and prevalence surveys.

Williams et al. (2012) noted that in a number of jurisdictions where both lifetime and current prevalence rates have been assessed, current rates have reduced more rapidly than lifetime rates and past year/lifetime ratios have decreased. Abbott et al. (2013) proposed that this might be a consequence of a decrease in incidence rates over time and an accumulation of people with longer duration problems as well as people who had problems in the past but who don’t currently. In Victoria the past 12 months 2008–2009 incidence rate was approximately half the past 2008 12 months prevalence rate (Billi et al. 2014a). This indicates that a substantial proportion of the current ‘stock’ of problem gamblers had developed problems recently. It is of interest that two-thirds of incident cases (‘inflow’) were people who, while not having experienced problems during the 12 months prior to the 2009 survey, reported having had problems in the past. Given that retrospective accounts of problem gambling have been shown to be highly conservative (Abbott et al. 2004), it is likely that the proportion of relapsing problem gamblers relative to new cases was even higher. While requiring replication and further investigation, it is hypothesised that this situation may characterise populations that have experienced long exposure to gambling and adapted to a substantial degree. It is further proposed that populations that have recently been exposed to continuous forms of gambling will have markedly different profiles, with a predominance of new cases and substantially lower proportions of people with long-term problems or who have overcome problems. If this is so, there are significant implications for policy and service delivery.

As outlined previously (Abbott 2006, 2007) in heterogeneous societies it is expected that there will be population sectors that have experienced long-term exposure and show signs of adaptation to varying degrees as well as sectors that have been recently exposed. In these latter groups, while relatively low proportions of people participate, those who do are expected to be at very high risk for problem development. As mentioned, this includes youth, young adults and recent migrants from societies with lower exposure to gambling. Further research is required on these matters including examination of why some sub-populations adapt rapidly and why others continue to experience relatively high rates of gambling-related harm. In part this is likely to be a consequence of other vulnerability factors including low income and socioeconomic status, marginalisation, discrimination, low social capital and high rates of mental disorder.

The study findings have important implications for theory and practice. Orford stated “…the more a product is supplied in accessible form, the greater the volume of consumption and the greater the harm” (Orford 2005). He said he doubted many would argue with this in other areas of public health including the supply of alcohol and tobacco and that it would be surprising if this was not also true for gambling. In part, Orford’s statement is an expression of the total consumption model (Rose and Day 1990), where it is proposed, for a range of health risk indicators, that there is a strong association between the population mean and the prevalence of problems. It is assumed that when mean consumption, e.g. of alcohol, increases or decreases, the proportion of people with problems changes accordingly. There is support for this model for alcohol and some other health issues. It has provided a rationale for public policies that take a whole of population approach and aim at reducing harm by reducing overall exposure and consumption. It contrasts with at-risk approaches that focus on subpopulations at high risk and attempt to increase their resistance and resilience.

Although Orford and some others regard availability and adaptation hypotheses as alternatives, Shaffer et al. (1997) and Abbott et al. (1999) regarded them as applying at different times during periods of gambling expansion. Abbott (2006, 2007) proposed that both also occur simultaneously, with the relative balance influenced by a variety of factors relating to the agent (e.g. nature of gambling activities and their availability), host (individuals involved in gambling) and the wider social, cultural and economic environment. Furthermore, as discussed previously, in complex societies, there will be considerable variation across social groups with respect to exposure duration and responses to exposure. The findings of the present study are not consistent with the proposal that increased gambling availability invariably leads to increased participation. Nor are they consistent with the view that problems will always decrease when participation decreases. To the contrary, some population sectors that experienced substantial reductions in participation had higher levels of problematic gambling. The findings suggest that exposure and total consumption models are overly simplistic, especially when applied in settings that have had many years of exposure to and experience with a range of gambling activities. Given that reduced participation in some high-risk groups including young adults has not been associated with harm reduction, it is important to understand why this is the case and what other measures can be taken to reduce gambling-related morbidity.

In addition to providing information on changes in gambling participation and harm in Victoria this study has further highlighted the substantial impact that methodological differences can have on problem gambling prevalence estimates. Two features not previously assessed, namely whether or not the administration of problem gambling screens is restricted to people who engage in particular activities or at particular frequencies, were found to be important. Restricting screen administration in both of these ways, rather than administering it to past year participants in any gambling activity, generated substantially lower estimates. These methods were used in most of the earlier Australian surveys and were among the practices that Abbott and Volberg (2000) maintained would downplay the magnitude of serious problem gambling and associated economic and social costs. More recently most Australian surveys have not used the weekly participation criterion. Some however continued to exclude particular common gambling activities. From the foregoing it seems likely that the prevalence of problem gambling was much higher in the earlier Australian studies than they appear to be. This also means that subsequent apparent decreases have probably been greater than they appear. While careful examination of previous studies and the application of weights developed by Williams et al. (2012) and added to in the present paper can help to more accurately assess changes over time in problem gambling and related harm in Australia and elsewhere, going forward it would be more parsimonious to learn from past mistakes, apply current methodological best practice, and do so consistently.

In Stone et al. (2015) and the present study it was found that administering problem gambling measures to subsets of gamblers and assuming that excluded participants are non-problem gamblers, while reducing problem gambling prevalence estimates, has a much greater impact on estimates of moderate- and low-risk gambling. Although people in these categories have less severe problems than problem gamblers, in aggregate they account for more gambling-related harm (Abbott et al. 2014a, b). This is because they are far more numerous. Additionally, over time, they are at elevated risk to develop serious gambling problems (Billi et al. 2014a). For these reasons, among others, it is important to estimate their numbers as accurately as possible.

Notes

Calculations were based on gaming expenditure data from the Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation and Consumer Price Index from the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

References

Abbott, M. (2006). Do EGMS and problem gambling go together like a horse and carriage? Gambling Research, 18(1), 7–38.

Abbott, M. (2007). Situational factors that affect gambling behaviour. In G. Smith, D. Hodgins, & R. J. Williams (Eds.), Research and measurement issues in gambling studies (pp. 251–278). Burlington MA: Academic Press.

Abbott, M., Bellringer, M., Garrett, N., & Mundy-McPherson, S. (2014a). New Zealand 2012 National Gambling Study Overview and Gambling Participation, report number 1. Wellington: Ministry of Health.

Abbott, M., Bellringer, M., Garrett, N., & Mundy-McPherson, S. (2014b). New Zealand 2012: National Gambling Study: Gambling harm and problem gambling. (Vol. report number 2). Wellington: Ministry of Health.

Abbott, M., Bellringer, M., Vandal, A., Hodgins, D., Palmer, Du, Preez, K., et al. (2012). Effectiveness of problem gambling brief telephone interventions: A randomised controlled trial. Auckland University of Technology: Gambling and Addictions Research Centre: Auckland.

Abbott, M. W., Romild, U., & Volberg, R. A. (2013). Gambling and problem gambling in Sweden: Changes between 1998 and 2009. Journal of Gambling Studies. doi:10.1007/s10899-013-9396-3.

Abbott, M., & Volberg, R. (1991). Gambling and problem gambling in New Zealand. Wellington: Department of Internal Affairs.

Abbott, M. W., & Volberg, R. A. (1996). The New Zealand national survey of problem and pathological gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies, 12(2), 143–160. doi:10.1007/BF01539171.

Abbott, M. W., & Volberg, R. A. (1999). Gambling and problem gambling in the community: an international overview and critique: Report number one of the New Zealand Gaming Survey. Wellington: DIA.

Abbott, M., & Volberg, R. (2000). Taking the pulse on gambling and problem gambling in New Zealand: A report on phase one of the 1999 National Prevalence Survey (report number three of the New Zealand Gaming Survey). Wellington: Department of Internal Affairs.

Abbott, M. W., & Volberg, R. A. (2006). The measurement of adult and pathological gambling. International Gambling Studies, 6(2), 175–200.

Abbott, M. W., Volberg, R., Bellringer, M., & Reith, G. (2004). A review of research on aspects of problem gambling: Final report. London: Responsibility in Gambling Trust.

Abbott, M., Williams, R., & Volberg, R. (1999). Seven years on: A follow up study of frequent and problem gamblers living in the community. Report number 2 of the New Zealand Gambling Survey. Wellington: Department of Internal Affairs.

Billi, R., Stone, C. A., Abbott, M., & Yeung, K. (2014a). The Victorian Gambling Study (VGS) a longitudinal study of gambling and health in Victoria 2008–2012: Design and methods. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. doi:10.1007/s11469-014-9528-8.

Billi, R., Stone, C. A., Marden, P., & Yeung, K. (2014b). The Victorian Gambling Study: A longitudinal study of gambling and health in Victorian 2008–2012. Victoria: Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation.

Binde, P. (2005). Gambling across cultures: Mapping the worldwide occurrence and learning from ethnographic comparison. International Gambling Studies, 5(1), 1–27.

Binde, P. (2011). What are the most harmful forms of gambling? Analyzing problem gambling prevalence surveys. In (CEFOS Working Paper 12) (Ed.). Retrieved 8 May 8 2014, from the University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden. https://gupea.ub.gu.se/bitstream/2077/26165/1/gupea_2077_26165_1.pdf

Bogart, W. A. (2011). Permit but discourage regulating excessive consumption. England: Oxford University Press.

Department of Justice and Attorney General. (2011). Gambling Prevalence Study Standards. Victoria: Gambling Research Australia.

Dickerson, M. G., Baron, E., Hong, S. M., & Cottrell, D. (1996). Estimating the extent and degree of Gambling related problems in the Australian population: A national survey. Journal of Gambling Studies, 12(2), 161–178. doi:10.1007/BF01539172.

Ferris, J., & Wynne, H. (2001). In The Canadian Problem Gambling Index: Final Report. Ottawa. Retrieved from the Canadian Consortium for Gambling Research, 8 May 2014. http://www.ccgr.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/CPGI-Final-Report-English.pdf: Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse.

Gambling Review Body. (2001). Gambling review report. London: Her Majesty’s Stationary Office.

Hare, S. (2009). A Study of Gambling in Victoria: Problem gambling from a public health perspective. Melbourne: State of Victoria: Department of Justice.

Lesieur, H. R., & Blume, S. B. (1987). The South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS): A new instrument for the identification of pathological gamblers. American Journal of Psychiatry, 144(9), 1184–1188.

Marshall, D. (2005). The gambling environment and gambling behaviour: Evidence from Richmond–Tweed, Australia. International Gambling Studies, 5, 63–83.

National Research Council (NRC). (1999). Pathological gambling: A critical review. Washington DC: National Academy Press.

Orford, J. (2005). Complicity on the river bank: The search for truth about problem gambling: Reply to the commentaries. Addiction, 100(9), 1235–1239.

Productivity Commission. (1999). Australia’s Gambling Industries: Inquiry Report No. 10. Canberra: Retrieved on 6 June 2014 from the Productivity Commission. http://www.pc.gov.au/projects/inquiry/gambling/docs/report

Productivity Commission. (2010). Gambling Inquiry Report No. 50. Canberra: Retrieved on 6 June 2014 from the Productivity Commission. http://www.pc.gov.au/projects/inquiry/gambling-2009/report

Rose, G., & Day, S. (1990). The population mean predicts the number of deviant individuals. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 301(6759), 1031.

Sassen, M., Kraus, L., & Buhringer, G. (2011). Differences in pathological gambling prevalence estimates: Facts or artefacts? [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 20(4), e83–e99. doi:10.1002/mpr.354.

Shaffer, H. J., Hall, M. N., & Vander Bilt, J. (1997). Estimating the prevalence of disordered gambling behaviour in the United States and Canada: A meta-analysis Retrieved 8 May 2014 from. http://www.divisiononaddiction.org/html/publications/meta.pdf

Shaffer, H. J., LaBrie, R. A., LaPlante, D. A., & Nelson, S. E. (2004). The road less travelled: Moving from distribution to determinants in the study of gambling epidemiology. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 49(8), 504–516.

Stevens, M., & Young, M. (2010). Independent correlates of reported gambling problems amongst Indigenous Australians. Social Indicators Research, 98(1), 147–166.

Stone, C. A., Romild, U., Abbott, M., Yeung, K., Billi, R., & Volberg, R. (2015). Effects of different screening and scoring thresholds on PGSI gambling risk segments. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 13(1), 82–102.

Storer, J., Abbott, M., & Stubbs, J. (2009). Access or adaptation? A meta-analysis of surveys of problem gambling prevalence in Australia and New Zealand with respect to concentration of electronic gambing machines. International Gambling Studies, 9(3), 225–244.

The Centre for Gambling Research: Australian National University (2004). 2003 Victorian Longitudinal Community Attitudes Survey. Gambling Research Panel Report No. 6. Melbourne: Gambling Research Panel.

Tovim, B. D., Esterman, A., & Tolchard, B. (2001). The Victorian Gambling Screen. Report prepared for the Victorian Casino and Gaming Authority. Gambling Research Panel, Melbourne.

Treasury, Queensland. (2001). Queensland household gambling survey. Queensland: Queensland Government.

Vasiliadis, S. D., Jackson, A., Christensen, D., & Francis, K. (2013). Physical accessibility of gaming opportunity and its relationship to gaming environment and problem gambling: A sytematic review. Journal of Gambling Studies, 28, 1–47.

Volberg, R. (2004). Fifteen years of problem gambling prevalence research: What do we know? Where do we go? eGambling: Electronic Journal of Gambling Issues, 10, 1–19.

Wardle, H., Moody, A., Spence, S., Orford, J., Volberg, R., Jotangia, D., et al. (2010). British gambling prevalence survey 2010. London: National Centre for Social Research.

Wildman, R. W. (1998). Gambling: An attempt at an integration. Edmonton, Alberta: Wynne Resources.

Williams, R. J., & Volberg, R. A. (2010). Best practices in the population assessment of problem gambling. Retrieved 8 May 2014, from Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre. http://www.opgrc.org/content/research.php?appid=2500. Ontario: Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre.

Williams, R. J., Volberg, R. A., & Stevens, R. M. G. (2012). The population prevalence of problem gambling: Methodological influences, standardized rates, jurisdictional differences, and worldwide trends. Retrieved 8 May 2014 from. http://hdl.handle.net/10133/3068: Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care.

Acknowledgments

The Victorian Department of Justice, Victoria; The Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation; Elmer Villanueva; Paul Marden; Sarah Hare; Damien Jolley; Jan McMillen.

Conflict of interest

Christine Stone receives funding from the Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Abbott, M., Stone, C.A., Billi, R. et al. Gambling and Problem Gambling in Victoria, Australia: Changes over 5 years. J Gambl Stud 32, 47–78 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-015-9542-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-015-9542-1