Abstract

It has been estimated that 80% of Australians engage in some form of gambling, with approximately 115,000 Australians experiencing severe problems (Productivity Commission 2010). Very few people with problem gambling seek help and, of those who do, large numbers drop-out of therapy before completing their program. To gain insights into these problems, participants who had either completed or withdrawn prematurely from an individual CBT-based problem gambling treatment program were interviewed to examine factors predictive of premature withdrawal from therapy as well as people’s ‘readiness’ for change. The results indicated that there might be some early indicators of risk for early withdrawal. These included: gambling for pleasure or social interaction; non-compliance with homework tasks; gambling as a strategy to avoid personal issues or dysphoric mood; high levels of guilt and shame; and a lack of readiness for change. The study further showed that application of the term ‘drop-out’ to some clients may be an unnecessarily negative label in that a number appear to have been able to reduce their gambling urges even after a short exposure to therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Recently, the Australian Government’s independent and advisory body, the Productivity Commission (2010), released an inquiry report into Australian gambling. The findings indicated that approximately 115,000 Australians had ‘severe’ problems with their gambling and a further 280,000 were at ‘moderate risk’ for gambling problems. Although it could be suggested that, in terms of mental health, only a relatively small proportion of the population can be classified with a gambling problem, the magnitude of the issue is brought to light with an examination of the associated expenditure (gambling losses). During 2008–2009, all Australian gamblers generated total expenditure of just over $19 billion equating to an average of $1,500 per adult. The economic cost of problem gambling is estimated to be a significant $4.7 billion each year (Productivity Commission 2010). Such rates of problem gambling are not unique to Australia with similar data being reported by other developed countries. For example, problem gambling is reported to affect approximately 2.5% of the population in the United States (National Opinion Research Centre 1999), up to 2.9% of Canadians (Cox et al. 2005), 1.2% of New Zealanders (Abbott and Volberg 2000) and 0.8% of the British population (Sprosten et al. 2000).

Electronic gaming machines (EGMs), in particular, pose substantial risks for regular players (Delfabbro 2008). Findings reported by the Productivity Commission (2010) suggest that around 600,000 Australians (four per cent of the adult population) play EGMs at least weekly. Approximately fifteen per cent of these regular EGM players are ‘problem gamblers’ and it is estimated that this group spend 40 per cent of the total national expenditure on EGMs (Productivity Commission 2010).

Aetiology of Problem Gambling

In terms of the development of problem gambling, some argue for dispositional causes while others believe it is fundamentally cognitive or behavioural in nature. Blaszczynski and Nower (2002) advanced a pathways model which integrates potential influences from a variety of factors including biological, personality, developmental, cognitive, learning, and ecological variants. They suggested three distinct subgroups of gamblers, all of whom experience impaired control over their behaviour. The groups include: those with gambling problems which have been behaviourally conditioned (e.g. Anderson and Brown 1984; McConaghy et al. 1983); those who are emotionally vulnerable to problem gambling through family history (e.g. Lesieur and Rothschild 1989), those with predisposing personality characteristics and life events (e.g. Anderson and Brown 1984; Jacobs 1986); antisocial, impulsive problem gamblers (e.g. Blaszczynski et al. 1997) or those with attention deficit (e.g. Rugle and Melamed 1993). Blaszczynski and Nower proposed that the ‘starting block’ for all problem gambling is accessibility, citing higher levels of problem gambling in areas where public gambling facilities exist.

Treatment for Problem Gambling

Besides significant financial loss, problem gambling has also been found to be associated with a range of issues and co-morbid conditions including legal and occupational difficulties, family problems, psychological distress, and suicide (Welte et al. 2001). Typically, the presentation of problem gambling is complex and varied, and perhaps as a result of this, a number of treatment approaches have been applied, with varying levels of success.

Most research into treatments for problem gambling suffers methodological flaws, limiting the extent to which firm conclusions can be drawn about the efficacy of gambling treatments (Blaszczynski 2005; Dowling et al. 2008; Toneatto and Ladouceur 2003). Some of these methodological issues include: small sample sizes; a tendency to use measures assessing gambling behaviour in insufficient detail to allow the full range of outcomes to be considered (rather, a preference for use of dichotomous categories such as success or failure can be found); an absence of baseline data; a lack of standardised treatments; little evidence to suggest that treatments were administered reliably; and insufficient attention paid to the mediation or process of behaviour change. Toneatto and Ladouceur stated that there is “very little firm scientific knowledge about what constitutes effective treatment for pathological gambling” (p. 291). However, the psychotherapeutic approaches most commonly applied (based on their efficacy) are cognitive therapy, behavioural therapy, and a combination of both—cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT).

Some support has been found for cognitive approaches which typically focus on cognitive correction—the identification and correction of erroneous perceptions of randomness (Ladouceur et al. 2003). Behavioural interventions usually draw upon techniques such as ‘imaginal desensitisation’ and in vivo exposure to gambling situations. Essentially, both these approaches aim to have problem gamblers experience urge to gamble and to allow this urge to diminish without engaging in gambling behaviour. There is sufficient evidence within the published research to suggest that the behavioural treatment approach is likely to have a positive impact, particularly with EGM users, with 30–80% of participants abstaining from gambling post-treatment (Echeburúa and Fernández-Montalvo 2005). However, CBT is credited with holding the greatest amount of empirical support in the treatment of problem gambling (Toneatto and Ladouceur 2003).

Treatment Drop-Out

In broad terms, drop-out refers to the client cessation of therapy prior to the end of the treatment plan, although the term has been used to describe clients who consent to treatment but drop-out before commencing right through to clients who complete their treatment program, but do not attend follow-up sessions (Walker 2005). Aside from the impact that early drop-out might have on the therapeutic success of an intervention, it may potentially affect research findings if factors such as randomisation of participants and study power are not carefully considered (De Jong et al. 2010).

Adding further complexity to the issue of accurately assessing treatment efficacy, recent research has indicated that a large percentage of individuals with problem gambling do not seek formal assistance for gambling problems. Although a number of explanations have been advanced to account for the discrepancy between official prevalence estimates and treatment populations, it is thought that a number of people spontaneously change their gambling behaviour either using self-help methods or via a form of ‘natural recovery’ (Hodgins and El-Guebaly 2000). Longitudinal studies of gamblers (e.g. Abbott et al. 1999; Haworth 2005) have found that people assessed as problem gamblers at one point in time often will not be so classified when interviewed subsequently. Indeed, Walker (2005) has argued that appraisals of treatment efficacy should take the phenomenon of natural recovery into account to a greater extent, for it follows that it will influence both help-seeking as well as drop-out rates irrespective of the therapeutic approach that is adopted.

Researchers employ various methods to measure client drop-out: Sylvain et al. (1997) relied on therapist judgement regarding the appropriateness of treatment termination. That is, drop-out was deemed to have occurred at any stage if the therapist felt that the client needed further treatment. A more commonly employed method is where the measurement of drop-out is based on the number of sessions that a client had attended (Robson et al. 2002). Some researchers have reported that most drop-outs from treatment for problem gambling tend to occur either before treatment has commenced or after the client has attended only one or two sessions (Robson et al. 2002; Sylvain et al. 1997). Perhaps as a reflection of these broad categorisations of drop-out, ranges of drop-out rates vary quite considerably, although most research reports high rates, often in the vicinity between 30 and 50%. Although CBT is the treatment approach with the greatest amount of empirical evidence to support its effectiveness, drop-out rates appear to be comparable to those associated with other treatment approaches (Ladouceur et al. 2001).

Models for Treatment Drop-Out

Although no formal models for treatment drop-out among problem gamblers have been proposed, Prochaska et al. (1992) put forward a model to explain behaviour change which has been frequently cited in the explanation of withdrawal or drop-out from treatment for addictive behaviours.

Prochaska et al. (1992) suggested that people contemplating a change in behaviour move through five stages of readiness—pre-contemplation (where there is no intention for change in the near future often due to a lack of awareness that there is a problem); contemplation (where the problem has been recognised and while the person is seriously thinking about change, they have not yet made a commitment towards it); preparation (where the person has made some change but has not yet reached an effective action, usually abstinence); action (overt changes are made requiring considerable effort and commitment for anywhere between 1 day and 6 months); and maintenance (where people work to consolidate gains and prevent relapse after 6 months).

Prochaska et al. (1992) pointed out that people typically spiral backwards and forwards through the stages a number of times before stable change is achieved and offer this as an explanation for large numbers of addicted people dropping out of treatment programs after registering. That is, rather than maintaining a linear progression through the stages of change, the nature of addiction results in the majority experiencing relapse. Relapse is typically accompanied by feelings of failure, shame, humiliation, and embarrassment. These unpleasant feelings often result in avoidance and resistance and Prochaska et al. (1992) suggested that this is the reason that many people will return to the pre-contemplation stage, often for long periods of time.

Drop-Out from Treatment for Problem Gambling

A small number of researchers have examined the factors that influence drop-out from therapy for problem gambling, each citing quite varying factors: psychological distress and obsessive–compulsive symptoms (Jimeneez-Murcia et al. 2007); absolute treatment goals, especially one of ‘total abstinence’ (Blaszczynski 1998) as opposed to ‘controlled gambling’ (Robson et al. 2002); and state anxiety (Echeburúa et al. 1996). Melville et al. (2007) conducted a systematic review of the literature in the area. Overall, they concluded that there was little support for the suggestion that demographic data such as age, gender, income level, years of education, ethnicity, and relationship status were useful predictors of drop-out from therapy for problem gambling. Similarly, they found little evidence to assert that higher levels of gambling debt and severity of gambling pathology, depression, anxiety, impulsivity, substance use, previous experience with psychotherapy, nor type of gambling behaviour (e.g. pokies, races, casino games) were influential over therapy compliance. However, they did find some evidence, albeit inconclusive, that some factors may be correlated with greater propensity for drop-out from therapy. These factors included: unemployment; high levels of stress combined with limited coping strategies; lower levels of social support; and earlier age of onset and greater duration of gambling (for example, Milton et al. 2002 found that those who had gambled at a problem level for 10 or more years were more likely to drop-out). Melville et al. (2007) also reported that research findings suggest that it is possible that those who hold greater belief in their distorted cognitions (such as gambler’s fallacy—a belief that independent events will influence or predict a subsequent, independent event) are more likely to experience frustration with cognitive therapy leading to non-compliance and drop-out. Although they only found one study which examined the extent to which motivation to change was an important factor in therapy completion, Melville et al. (2007) reported that the research method employed was such that firm conclusions could not be drawn with regards to the findings and recommended further research be conducted in this area.

In conclusion, there is a limited amount of data regarding client numbers and reasons for withdrawal from therapy for problem gambling (as well as broader clinical practice, Bados et al. 2007). The figures available vary widely according to the definition of drop-out used and the treatment approach followed and there is little qualitative data available reflecting the reasons why clients drop-out. Therefore, the aim of this study was to take a qualitative approach, incorporating client readiness to change, to examine the issues underlying drop-out from therapy for problem gambling, thereby offering future researchers a framework from which to develop further investigations.

Method

Design

The design was primarily qualitative in nature although some brief, structured questions drawing quantitative responses were also included.

Participants

Twenty-five people from the database of clients who had registered for treatment with State-wide Gambling Therapy Service (SGTS) were invited to participate in the present study. SGTS provides a CBT-based program drawing heavily upon cue and in vivo exposure. During the first session, clients are presented with a treatment rationale, individualised to their case so that they have a clear and early understanding about how their gambling urges are generated and maintained and the process by which the treatment aims to extinguish the urges. As a part of their exposure therapy, clients are asked to make short-term adjustments to their financial arrangements (cash restriction) so that they do not have access to cash, particularly during early sessions.

SGTS clients are all aged 18 years or more. Although a range of ages were represented, participants tended to be older with a mean age of 47.7 years and this is reflected in the relatively high number of retired participants. This mean age is, however, commensurate with the overall SGTS participant group mean age of 45.1 years. Table 1 below provides demographic and therapy details.

Recruitment

A purposive sampling process was followed—purposive sampling calls for the recruitment of sample groups who share particular characteristics (Bowling 1999). That is, two groups were approached: the first group (early withdrawal from therapy) comprised thirteen clients who had undergone at least an initial assessment session, but no more than two complete sessions. The second group (therapy completion) comprised twelve clients who had completed their entire treatment program through to discharge. These programs ranged in length from eight to twelve sessions. Following an initial invitation to participate, three clients (from the early withdrawal group) and two (from the completion group) returned contact indicating a desire to take part in the study. These clients were interviewed and an initial data analysis was completed to identify the relevant themes reflected in the data. Following this, an additional two clients were followed-up and interviewed for the early withdrawal group and an additional three from the completion group. No new themes emerged from any of these additional interviews and recruitment was ceased as data saturation was reached.

Ethics

Ethics approval for this study was granted by the Flinders University/Southern Adelaide Health Service, Flinders Clinical Research Ethics Committee/Clinical Drug Trials Committee and the University of Adelaide, School of Psychology Human Ethics Subcommittee.

Procedure

Initially, clients were contacted by letter to ascertain their interest in taking part in the study. They were informed that they were invited to participate in a one-on-one telephone interview and would be offered a $30 shopping voucher in appreciation of their time and effort. Those who indicated that they had an interest in participating were sent an information sheet and consent form. Each interview was conducted over the telephone and took between 40 and 80 min.

Instruments

Questionnaires

The first part of the interview was semi-structured. Broad questions (such as ‘Tell me about your gambling—how it developed and the influence it had’) were designed to give clients an idea of the area to be explored, but allow flexibility and divergence within their responses (Bowling 1999; Britten 2006). More specific questions were included in the interview guide for use when participants needed prompts. Key questions asked participants to describe: the factors surrounding the development of their gambling problem; what triggered the identification of their gambling as problematic; the impact of their gambling; any help or assistance they had sought; any gambling-related cognitions and urges (pre and post therapy); their goals and expectations for therapy; the levels of social support available to them; any factors facilitating either their completion or withdrawal from the therapy program; their reactions to specific therapy approaches such as cue exposure and cash restriction; and any impacts they felt the therapy had made on their level of gambling.

The information was analysed thematically as it was collected and interview questions were refined to capture any themes emerging from the data.

In addition, a short instrument employing structured questions was employed to gather exploratory data about participants’ readiness to change at the time that they entered therapy. This questionnaire was based on the Trans-theoretical Model of Change by Prochaska et al. (1992) and an existing questionnaire which has been amended to suit a problem gambling audience by Petry (2005). Participants were asked to respond on a scale of 1 (definitely false) through to 7 (definitely true), the extent to which they agreed with a total of 27 statements. The statements aimed to capture the stage of change (retrospectively) that participants were at just before they entered therapy. That is, the instrument captured the extent to which participants were likely to be at a pre-contemplative stage (‘As far as I was concerned, I didn’t have any problems with gambling that needed changing’, contemplative stage (‘I decided it could be worthwhile to work on my problem with gambling’), active stage (‘I was really working hard to change my gambling’), or maintenance stage (‘It worried me I might slip back on a problem with gambling I had already changed, so I was there to seek help’).

Data Analysis

As described above, the interviewer (first author) asked a series of pre-prepared questions, the majority of which were designed to elicit responses related to the client’s problem gambling and experience with therapy. Due to restrictions under a broader ethics approval for research with the SGTS client group, interviews were not recorded. However, the interviewer made extensive notes, as close as possible to verbatim.

As the purpose of the research was exploratory, the data were analysed using thematic analysis as outlined by Pope et al. (2006). The first stage of analysis was to aggregate the individual interview data into a contextual database, initially according to question number. The second stage was to code the material where concepts were generated and sorted to recurring themes and items of interest. The first author and a research associate, working separately, manually examined the transcripts for concept occurrences. Categories were added such that they were as inclusive as possible in an attempt to capture as many nuances in the data as possible. Some of these categories reflected general concepts such as ‘time spent gambling’ and ‘recalling losses or wins’. Other categories were more deductive, reflecting concepts such as the ‘role of guilt and shame’. Each of these categories was then examined for differences between the therapy completion group and the early withdrawal group.

Lastly, comparisons were made between the categories and group differences generated by the researcher and associate. There were no fundamental differences between the initial categories generated by the two people coding the data, although categories were discussed, and by agreement, merged or adjusted to ensure that each was meaningful and that the categories incorporated each piece of information collected through the interview process (Bowling 1999). For the sake of brevity, the categories reflected within the participant narratives are introduced in the next section which incorporates both the findings, supported with direct quotes, and a discussion to create context and meaning for each category (Green and Thorogood 2009). Differences between the early withdrawal group and the completion group are presented and discussed.

Results and Discussion

Overall, the data reflected a number of categories that participants felt had been influential in the development and treatment of their problem gambling. These included social influence, social learning and modelling, and avoidance of other negative stimuli such as stress. Participants also reflected on their ability (or lack thereof) to recognise their problem with gambling and the influence that this had over their readiness to seek help. When discussing their therapy, participants recounted difficult experiences during graded activities designed to generate exposure to gambling urges and many spoke of the difficulties that they had complying with challenging homework tasks. Some described changes in their beliefs and understanding about their probability of winning and their understanding of the programming of EGMs. Many also commented on the extent to which they did not feel able to draw on social support from friends or family during therapy due to fear of being negatively evaluated. Some of these descriptions of participant experiences with problem gambling and treatment may be useful to therapists when reflecting upon treatment approaches. Although not entirely definitive, a few differences between the participants who withdrew early from therapy and those who completed therapy were drawn and these may allow some factors to be considered indicative of early therapy withdrawal.

Social Influence and Avoidance in the Development of Problem Gambling

Research has shown that, for many, gambling is an activity that alleviates boredom, provides a feeling of pleasure, and facilitates social relationships (Grall-Bronnec et al. 2009). Pleasure and social interaction were also found to motivate a group of participants in the current study towards gambling—all those who did not complete therapy indicated that their gambling had started as some type of social activity.

Gambling on the horses has always been a part of my life. I like to have a beer and a laugh… (Aiden, aged 47, 2 sessions)

Before we had pokies in SA, my wife and I would go to Mildura with the kids about 3 times a year. At night we would go and play the pokies for a couple of hours together. (Garry, 68, 2 sessions)

I would go out with friends who gambled or someone would call and say let’s go gambling. (Ruby, aged 32, 3 sessions)

My friend and I would go together … (Samuel, aged 22, 2 sessions)

Although gambling is commonly cited as being a popular social activity for older adults (McNeilly and Burke 2001; Stitt et al. 2003), it is interesting to note that younger participants in this study who did not complete therapy also believed that their gambling was, initially, socially driven.

However, social interaction is not the sole driver for gambling behaviour; the American Psychiatric Association (2000) identifies gambling which is used as an escape from problems or to relieve dysphoric mood as a diagnostic criterion for pathological gambling. This is consistent with the findings of Wood and Griffiths (2007) who found that gambling as a form of escape from psychological distress or personal problems was the prime factor facilitating the continuation of gambling. Similarly, Morasco et al. (2007) reported that a negative emotional state was commonly reported as a trigger for gambling.

In the current study, gambling as a means of avoiding negative mood states was more common to those in the group who completed therapy as opposed to those who withdrew early. Completers tended to describe their initial motivations for gambling as being driven by solitude and escape rather than a social activity.

I… gambled because it was an easy way to relax. It was everywhere, accessible, and I used it as my switch-off time. (Mark, aged 40, 12 sessions)

At the time I had an unpleasant relationship with my partner and I was going to venues to get away… (Georgia, aged 74, 8 sessions)

However, gambling as a means of avoidance was not discussed exclusively by those who completed their therapy. Ruby, aged 32, completed only three sessions and also described her gambling as

…a wind-down, a place to escape from stress.

While the data indicated that there may have been a group difference in early motivation for gambling, future researchers may consider this worthy of further exploration as it is also possible that the tendency for those in the completion group to describe ‘avoidance’ as a reason for gambling may also be a result of greater understanding of personal motivators. That is, those who completed therapy may have benefited from a superior gambling-related self-awareness, facilitated by more time spent in therapy. This is consistent with the suggestion of Walker (2005) that time spent in therapy is often a strong predictor of successful outcomes.

Social Learning/Modelling and the Development of Problem Gambling

Along with classical and operant conditioning, learning theories have also been put forward as explanation of how problem gambling behaviour develops. That is, social learning theory suggests that social facilitation may serve to trigger and maintain gambling behaviours (Czerny et al. 2008). In a recent study, Fukushima and Hiraki (2009) employed a technique measuring changes to the scalp surface considered to be an index of reward processing. They employed this during a gambling task and found that participants responded, not only to their own losses, but also those of others. In addition, they found that self-reported measures of empathy were correlated with the magnitude of the scalp-surface response adding further weight to the suggestion that individuals are emotionally and physiologically affected by observing the wins and losses sustained by others when gambling.

Consistent with the premise that social learning can facilitate the development of problem gambling, individuals from both groups within the current study described situations which suggested that social learning or modelling had been an influence on the development of their gambling.

After leaving school, I lived with Dad. He trained greyhounds and we used to go to the dogs and trots a lot. I learnt to gamble on them from an early age. (Mick, aged 31, 2 sessions)

I was working in hospitality—I was surrounded by it. I started having a drink and a flutter after work and it grew from there. (Issac, aged 50, 8 sessions)

Social learning was clearly an important factor in the development of problem gambling for several participants, but this was true for participants in both groups and could not be used to identify those more likely to withdraw or complete therapy. Participants from both groups recognised the importance of acknowledging not only the past influence of social learning on the development of their problem gambling, but also its potential influence into the future.

I used to hang out with friends who were gamblers. I still see them, but I don’t hang out with them anymore. (Mick, aged 31, 2 sessions)

This is an important point for therapists working with clients who elect not to confide in family or friends about their problem with gambling. It is likely that such clients will be struggling not only with their own urges to gamble, but also encouragement or requests to gamble from people who have previously been part of their gambling network and need help to develop strategies to manage these relationships successfully as they withdraw from gambling.

Impact of the Gambling Problem

Consistent with reports in the literature that gambling is associated with psychological issues as well as financial problems (Oei and Gordon 2007; Weinstock et al. 2008), most participants in the current study reported experiencing both psychological and financial distress as a result of their gambling. This distress was reported by members of each group and could not be considered as a point of differentiation.

I…slipped into a state of deep depression. I stopped eating and started thinking horrible thoughts [suicidal ideation]. I was getting headaches and had to keep checking things, like making sure I had locked the car, even though I knew that I had. (Prue, aged 65, 12 sessions)

I hated myself. I wanted to take my own life and probably would have if I didn’t have my children. (Georgia, aged 74, 8 sessions)

I was spending all of my pay on the races and all of my time gambling which was affecting my relationship. My relationship broke up because of this. (Mick, aged 31, 2 sessions)

…the money ran out and we had to sell the house to the kids. (Garry, aged 68, 2 sessions)

Similarly, members from both groups described improvements in their psychological states once they experienced some degree of mastery over their gambling urges.

…I was so much better…where I had felt like taking my life, I no longer felt like that. (Georgia, aged 74, 8 sessions)

I have no fear now. It’s [my gambling] under control. (Issac, aged 50, 8 sessions)

It was such a relief, feeling like I had control over my urges. (Richard, aged 48, 8 sessions)

My life is back to normal. The way I want it to be. (Samuel, aged 22, 2 sessions)

I feel like I have been helped a lot because I have learnt what to do with my urges. (Mick, aged 31, 2 sessions)

Recognition of Problem Gambling and Help-Seeking

Research findings suggest that only about 10% of problem gamblers seek help (Ladouceur et al. 2001) and suggest that shame and humiliation (Pulford et al. 2009) and an inability to recognise when gambling becomes problematic (Splevins et al. 2010) are contributing factors. All but one participant across the current study indicated that they had been gambling for a number of years and that their gambling habits had gradually, almost insidiously, developed to become problematic. Evans and Delfabbro (2005) also reported findings suggesting that help-seeking in Australian problem gamblers was driven by the development of crises rather than by recognition of gambling behaviour being problematic. This is consistent with reports from participants across both groups in the current study where all but one participant described a moment when they were forced to acknowledge that their gambling was no longer under control. Although members of both groups indicated that they had a certain level of awareness that their gambling was becoming problematic (anywhere from 6 months to several years prior), it was at the point of crisis that help was sought.

I was sacked from my job for stealing money. I had a nervous breakdown, ending up in hospital… (Issac, aged 50, 8 sessions)

I wanted to take my own life… (Georgia, aged 74, 8 sessions)

…I had now stolen something… (Prue, aged 65, 12 sessions)

…I couldn’t eat, couldn’t concentrate on my study, couldn’t sleep…I didn’t do my exams. (Samuel, aged 22, 2 sessions)

My relationship broke up because of this. (Mick, aged 31, 2 sessions)

These participant reports suggest that participants were either unable or unwilling to recognise earlier warning signs that they were becoming dependent upon gambling.

Consistent with this poor ability to recognise that their gambling had become problematic, it is noteworthy that only one participant actively sought information about therapy services available. This was the only difference found between the groups in terms of their help-seeking behaviour as all of the other participants reported that they had either been referred to SGTS by another professional (counsellor, social worker, or hospital staff) during their crisis, or that a friend or family member had sourced information for them.

Having acknowledged that they had a problem with gambling, most of the participants spoke of the shame and self-loathing that they experienced as a result with many seeking to hide their problem from even close friends and family. Scull and Woolcock (2005) also found that gambling is an issue generating enormous shame and stigma in Australia for both problem gamblers and their families, particularly those from non-English speaking backgrounds. Therefore, it is suggested that future public education might specifically seek to improve recognition of early warning signs for problem gambling as well as attempt to normalise problem gambling in order to reduce the stigma that currently surrounds it. That is, gambling does not hold the same medical rationale for addiction as do substances such as alcohol (Preston and Smith 1985) and this possibly makes it more difficult to empathise with those with problem gambling as attributions of blame tend to be left with the individual rather than the ‘disease’.

There were a number of participants who had sought help on several occasions from a variety of counsellors, while others had only spent time with a therapist from SGTS. However, these differences were not in line with membership of either group. Of those who had sought help elsewhere, participants reported that they found that the cue exposure approach used by SGTS therapists was more focussed and useful than the more general counselling therapies that they had otherwise experienced.

…they had more of a technique than the other counsellors… (Mark, aged 40, 12 sessions)

Mastery Over Gambling Urge

Therapies addressing gambling urges typically encompass psycho-education about urge extinction along with in vivo exposure sessions. Research has shown evidence to support this approach. Grimard and Ladouceur (2004) for example, found that that cognitive behaviour therapy was useful for improving individual perceptions of control over gambling urge. In line with this, they also reported that participants reduced the frequency of their gambling sessions as well as the amount of money they gambled and that these gains were maintained for 6 months following treatment.

SGTS offers therapy with a significant focus on psycho-education and urge control and, in the current study, participants across both groups reported that they were more aware of their urges and much better able to manage them, regardless of the time that they had spent in therapy.

…I have learnt what to do with my urges… (Mick, aged 31, 2 sessions)

I now understand what the urge is and how to control it. I can manage it now. (Samuel, aged 22, 2 sessions)

Back then I didn’t feel like I had a lot of control. Now I have better control [over urges]… (Mark, aged 40, 12 sessions)

Blaszczynski et al. (2005) conducted a treatment designed for clients to use at home. The therapy incorporated the use of a pre-recorded audiotape designed to take clients through an imaginal desensitisation exercise and required only one therapy session, although clients were asked to practice three times a day for 5 days. The treatment was remarkably successful with 79% of participants (n = 37) reporting a positive treatment response of either ‘abstinence’ or ‘controlled or significantly reduced gambling’ after a 2-month follow-up. Similarly, it is possible that cue exposure might, for some clients, be very successfully applied as a short course over a small number of sessions. As offered by SGTS, it may be that psycho-education through case conceptualisation, outlining of the treatment rationale, and brief exposure practice are sufficient for many clients. This would also suggest that such clients might quite justifiably be considered to have successfully completed therapy, rather than be automatically considered as drop-outs. Indeed, clients who had withdrawn from their therapy early voiced confidence in the skills that they had developed through therapy as did those who completed a full program.

I would rather do it myself [than seek therapy elsewhere], especially as I have the tools I need now [to manage my gambling urges]. (Mick, aged 31, 2 sessions)

However, when asked about the possibility of relapse, all members of the group who withdrew from therapy early acknowledged the possibility as opposed those who had completed a full program of therapy who tended to be more confident in their ability to abstain.

I know I could relapse, and I will come back [for more therapy] if I need. (Samuel, aged 22, 2 sessions)

I know I could relapse. That’s just the reality. (Ruby, aged 32, 3 sessions)

No fear [of relapse]. It’s under control. (Issac, aged 50, 8 sessions)

I am confident I will not relapse. I am sure. (Gisela, aged 74, 8 sessions).

It appears that, although the exposure technique was useful to all participants, it might also result in early perceptions of control for some clients, thereby facilitating increased levels of confidence and reduced perception of need for therapy beyond the initial few sessions. While this short-term therapy might be useful, the current study has not examined the extent to which this confidence in ability to control urges persists over time. What is also unknown is the extent to which those who persisted with therapy experienced early confidence in their ability to manage their urges. From a retrospective view, it appears possible that early perceptions of mastery over urge may facilitate early withdrawal from therapy, although future research would be better placed to discuss this accurately if it were conducted prospectively. Further research is also needed to examine the extent to which those who withdraw early from therapy are able to maintain their urge control over time compared with those who complete therapy programs.

Social Support During Therapy

Research has indicated that lower levels of social support are correlated with therapy drop-out (Melville et al. 2007). Social support was certainly a facilitating factor in some participants seeking help in the current study, however, it was not a point of differentiation between groups in terms of the number of therapy sessions attended.

Within both groups there were participants who were afraid to tell anybody at all about their gambling problems and there were participants who had shared their story with a friend or family member. Of those who had confided in another, every participant reported that they had received encouragement to attend therapy sessions. One of the people who had completed her therapy reported that her daughter had attended every single session with her, but also reiterated that she would definitely have attended by herself even if she had not had such a high level of support.

…my youngest daughter came to therapy with me and she talked about what my gambling meant to her, how she felt. Then I was able to talk. That felt better, just being able to talk. (Georgia, aged 74, 8 sessions)

While social support did not appear to be a crucial factor in terms of therapy completion, as discussed in an earlier section, social support may hold increased levels of importance post-therapy, especially for those who have historically gambled with family or friends who continue to gamble. In this situation, social support may be an important consideration in terms of relapse prevention.

Identification of Self as Separate from the Gambling ‘In-Group’

Interestingly, two of the five participants who had completed therapy programs reported what seemed almost to be an epiphany for them. They recalled that during the course of their therapy, they had returned to venues in order to practice extinguishing urge by sitting in front of a machine, placing money in it, and refraining from gambling. During this homework practice, both noticed those around them in the venue for what seemed to them to be the first time. They were both struck by the number of elderly people who seemingly had nothing else to do but gamble for hours on end. Both reported experiencing an emotional realisation that this, but for their therapy, had been their fate. There was an acute perception that problem gamblers were a group and an almost vehement personal disassociation from this group.

…there were all these old people, sitting on the step, waiting for the venue to open. I suddenly realised what gambling does to people, that I could have been one of them. (Prue, 65, 12 sessions)

Now I can sit and see the others, what they are doing. I see who they are. Other people must have looked at me that way. (Georgia, aged 74, 8 sessions)

While this information was not particularly useful in differentiating between those likely to complete and those likely to withdraw early from treatment, it may be a further factor worthy of consideration in future investigations into gambling relapse.

Gambling-Related Cognitions

Irrational or faulty cognitions have been shown to be positively correlated with risky gambling behaviour. For example, Miller and Currie (2008) reported a finding suggesting, not surprisingly, that people engaging in risky gambling practices spent more of their income on gambling when they had more irrational gambling cognitions compared to those with fewer irrational cognitions. Although some participants in the current study reported experiencing irrational beliefs about the probability that they would win each time they gambled (particularly at the time that they were experiencing urges), this could not be used to identify individuals at risk of early withdrawal from therapy. That is, participants across both groups, believed that winning came down to luck rather than a specific ability or skill. Some believed, before therapy, that they were particularly lucky people:

I did have a favourite machine and thought I was lucky on this one. (Georgia, aged 74, 8 sessions).

Some days, I just felt lucky. (Richard, aged 48, 8 sessions)

However, most reported having a better understanding of how the machines worked after therapy and articulated a clear, functional appreciation for their probability of winning.

In terms of other gambling-related cognitions, there was no evidence of group differences as all but one participant reported finding it easier to recall wins rather than losses when they were caught in their gambling cycle and all but one reported that they were strongly motivated to continue gambling in order to recoup their losses.

Participant Perceptions of Therapy

Importantly, all participants reported that they had established good relationships with their therapists and that their expectations of therapy were met or exceeded, negating the possibility that this might differentiate early withdrawal participants from those who completed therapy in this study. All participants found the frequency and length of sessions to be appropriate and the cue exposure technique useful.

…it [cue exposure] gave me a better understanding of how it all works. (Aiden, aged 47, 2 sessions)

…writing down details about my urges helped me to understand them. (Mick, aged 31, 2 sessions)

Similarly, none of the participants reported any problems with wait times, questionnaire completion, or confidentiality/anonymity and this was not cited by any participant as a reason for withdrawing from therapy.

Homework Compliance and Relapse

All those who completed therapy reported finding their homework tasks difficult and time-consuming, but claimed that they had pushed themselves and complied fully. Similarly, those who had withdrawn from therapy all reported finding the homework tasks difficult although some reported that they did not engage with them fully.

I didn’t do them. The cash restriction was hard because I run small businesses…it was just too hard. (Aiden, aged 47, 2 sessions)

…there is some stuff I still haven’t done because I’m too scared to stop avoiding [my urges]. (Mick, aged 31, 2 sessions)

As with clients undertaking CBT for any disorder, it seems that problem gamblers struggle to comply with homework tasks during therapy. This is perhaps exacerbated for people with gambling problems by a fear that the tasks will result in relapse. It has also been shown that non-compliance may be associated with problematic therapeutic alliance (Dunn et al. 2006; Helbig and Fehm 2004). Counsellors interviewed by Jackson et al. (2000) about their beliefs surrounding the importance of therapeutic alliance reported that they believed therapeutic relationship to be of the utmost importance to their practice; they all believed that a strong alliance was imperative for positive change to occur.

Alternatively, as reported by one participant in this study, clients may feel that they are letting their therapist down if they do not comply with difficult tasks or if they relapse during therapy and prefer to withdraw from treatment as this seems preferable to disclosing ‘failure’ to a therapist. This is also reflected in comments by Petry (2005) who suggested relapse is typically accompanied by feelings of shame, humiliation, and embarrassment.

I just felt like, after all the effort they had put in, I didn’t want to let them, or myself, down. (Georgia, aged 74, 8 sessions)

Therefore, the findings indicate that in some cases, homework non-compliance may be associated with fear of relapse and may facilitate early treatment withdrawal, thus emphasising the need for a strong therapeutic alliance and early, frank discussions between therapist and client about the possibility, but not the definite fatality, of relapse during therapy.

Participant Reasons for Withdrawing from Therapy

Aside from reporting feelings of confidence and mastery over their gambling urges, other reasons that participants offered for leaving therapy after a small number of sessions were related to lifestyle factors such as securing a new role in a remote, rural location and having to care full-time for a family member (thereby effectively eroding any opportunity to gamble or attend therapy). Two participants also reported that their therapist had moved from their role, and, rather than “start all over again” with a new therapist, they had elected to leave therapy with the skills that they had acquired to that point. That is, unavoidable lifestyle changes affecting either the therapist or the client contributed to a significant number of therapy withdrawals in this small sample. None of the studies cited here incorporated lifestyle factors in their predictive models of therapy drop-out and it may be worthy of further consideration for those conducting larger quantitative projects in the future.

Treatment Goals

There are some reports that treatment goals may impact on therapy drop-out rates with participants finding it more difficult to adhere to treatments which demand ‘total abstinence’ (Blaszczynski 1998) as opposed to ‘controlled gambling’ (Robson et al. 2002). Unsurprisingly, others have found that such differences dissipate if clients are allowed to choose between therapy goals of abstinence or controlled gambling or to set their own goals (Dowling et al. 2009). SGTS clients are encouraged to set their own therapy goals and these were examined to see if there were any differences in the types of goals set between the two groups. There was no clear indication from participants in this study that therapy goals, if set by the client, would serve to predict drop-out. Clients across each group had set mixed goals incorporating both total abstinence and controlled gambling.

I was expecting to be cured. I don’t feel cured. I do still gamble, but I set limits and it is controlled. (Issac, aged 50, 8 sessions)

My goal for therapy was either a massive reduction in my gambling or, hopefully, a total cessation of the activity. I have slowed down, but I’m still gambling which I don’t like. (Mark, aged 40, 12 sessions)

I didn’t expect it [therapy] to work at all. I wanted to stop completely. I now have no wish to gamble. I think of it every now and then, but I do not want to go back. (Georgia, aged 74, 8 sessions)

I’m not silly. I’m not someone to gamble everything away. I just wanted to gain better control. (Aiden, aged 47, 2 sessions)

I wanted to stop gambling and not to play at all. That was the ultimate goal. (Ruby, aged 32, 3 sessions).

While some participants indicated that they had not reached their initial goal of total abstinence, all reported that they felt more in control of their urges than they had prior to treatment. Some indicated that they had come to alter their expectations through the course of therapy.

I now realise that the expectation of a cure wasn’t realistic. (Issac, aged 50, 8 sessions),

However, even if early expectations of therapy were set high and initial goals were not ultimately met, this was not found to be associated with decisions to either withdraw from or complete therapy.

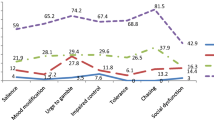

Stages of Change

Data gathered regarding participant readiness for change was intended to be exploratory in nature and was motivated by results from an earlier study by Petry (2005) which generated findings indicating that an individual’s state of readiness for change may have an impact on outcomes of treatment for problem gambling. In this study, participant numbers were too small to return meaningful results from statistical analyses and participants were encouraged to support their responses with qualitative explanation. However, mean scores were calculated for each of the stages of change in the model to provide some indication of participant response tendencies. Although there were no clear differences in responses between the completion and early withdrawal groups on measures of pre-contemplation, contemplation, or maintenance behaviours, there was some indication that there may have been a difference between groups when responding to items designed to capture commitment to action. That is, those who completed therapy tended to agree more strongly (M = 40.8) than did those who withdrew in the early stages of therapy (M = 31.8) to items such as “I was really working hard to change my gambling” and “At times my problem with gambling was difficult, but I was working on it”. Although not conclusive evidence, this finding does indicate that future research might usefully explore client readiness to change as it is possible that commitment to action (and possibly commitment to engage in homework tasks) may contribute to the indication of early withdrawal. These results should be treated with some caution as the interview was conducted retrospectively. Further exploration of client readiness to change should capture attitudes and beliefs prior to commencement and throughout therapy.

Clinical Implications

While this study included only a small number of participants and data collection was limited to note-taking rather than complete voice recordings, the findings do offer some outcomes that may be worthy of investigation for future researchers. That is, although the results did not identify a definitive range of factors predisposing individuals to early withdrawal from therapy, there may be some early indicators of higher risk for early withdrawal: gambling for pleasure or social interaction; non-compliance with homework tasks; gambling as a strategy to avoid personal issues or dysphoric mood; high levels of guilt and shame; and an inappropriately developed stage of readiness for change. The findings support previously published research suggesting that homework compliance is often an issue in cognitive and behavioural therapies and may lead to withdrawal from therapy, particularly where therapeutic alliance has not been fully established, or for people with problem gambling, fear of relapse has not been adequately addressed. Therefore, it is important that clients have reached, or are coached towards, an ‘action’ stage of change before challenging homework tasks are set. Therapists might also find it beneficial to take care to evaluate and address client shame, embarrassment, and fears of stigma during the very early stages of therapy. It may also be useful to examine the benefits that clients obtain from their gambling and to help generate alternative, functional strategies that provide similar benefits, particularly for clients who gamble to avoid other personal problems or symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression and for those who gamble for pleasure or to engage in social interactions.

Finally, and importantly, the results also revealed information suggesting that the term ‘drop-out’ and the associated connotations of failure may need to be reconsidered. While two of the participants who withdrew early from treatment did so because of unavoidable life-style changes, all of those who withdrew and agreed to take part in the research reported that they had benefited significantly from their brief exposure to therapy and felt that they were better able to manage their gambling urges as a direct result of the therapy sessions that they had attended.

References

Abbott, M. W., & Volberg, R. A. (2000). A report on phase one of the 1999 national prevalence survey: Taking the pulse on gambling and problem gambling in New Zealand. Wellington: Department of Internal Affairs.

Abbott, M. W., Williams, M., & Volberg, R. (1999). Seven years on: A follow-up study of frequent and problem gamblers living in the community. Report no. 2 of the New Zealand gambling survey. Wellington: Department of Internal Affairs.

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of the mental disorders (text revision) (4th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Anderson, G., & Brown, R. I. F. (1984). Real and laboratory gambling, sensation seeking and arousal: Toward a pavlovian component in general theories of gambling and gambling addiction. British Journal of Psychology, 75, 401–411.

Bados, A., Balaguer, G., & Salaña, C. (2007). The efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy and the problem of drop-out. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 63, 585–592.

Blaszczynski, A. (1998). Overcoming compulsive gambling: A self-help guide using cognitive behavioural techniques. London: Robinson Publishing.

Blaszczynski, A. (2005). Conceptual and methodological issues in treatment outcome research. Journal of Gambling Studies, 21, 5–11.

Blaszczynski, A., Drobny, J., & Steel, Z. (2005). Home-based imaginal desensitization in pathological gambling: Short-term outcomes. Behavior Change, 22, 13–21.

Blaszczynski, A., & Nower, L. (2002). A pathways model of problem and pathological gambling. Addiction, 97, 487–499.

Blaszczynski, A., Steel, Z., & McConaghy, N. (1997). Impulsivity in pathological gambling: The antisocial impulsivist. Addictions, 92, 75–87.

Bowling, A. (1999). Research methods in health: Investigating health and health services. Philadelphia: Open University Press.

Britten, N. (2006). Qualitative interviews. In C. Pope & N. Mays (Eds.), Qualitative research in health care (3rd ed., pp. 12–20). Carlton, VIC: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Cox, B. J., Yu, N., Afifi, T. O., & Ladouceur, R. (2005). A national survey of gambling problems in Canada. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 50, 213–217.

Czerny, E., Koenig, S., & Turner, N. E. (2008). Exploring the mind of the gambler: Psychological aspects of gambling and problem gambling. In M. Zangeneh, A. Blaszczynski, & N. E. Turner (Eds.), In the pursuit of winning: Problem gambling theory, research and treatment (pp. 65–82). New York: Springer Science and Business Media.

De Jong, K., Moerbeek, M., & van der Leeden, R. (2010). A priori power analysis in longitudinal three-level multilevel models: An example with therapist effects. Psychotherapy Research, 20, 273–284.

Delfabbro, P. H. (2008). Australasian gambling review (AGR) fourth edition (1992–2008). Adelaide: University of Adelaide.

Dowling, N., Jackson, A. C., & Thomas, S. A. (2008). Behavioural interventions in the treatment of pathological gambling: A review of activity scheduling and desensitization. International Journal of Behavioral Consultation and Therapy, 4, 172–187.

Dowling, N., Smith, D., & Thomas, T. (2009). A preliminary investigation of abstinence and controlled gambling as self-selected goals of treatment for female pathological gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies, 25, 201–214.

Dunn, H., Morrison, A. P., & Bentall, R. P. (2006). The relationship between patient suitability, therapeutic alliance, homework compliance and outcome in cognitive therapy for psychosis. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 13, 45–152.

Echeburúa, E., Báez, C., & Fernández-Montalvo, J. (1996). Comparative effectiveness of three therapeutic modalities in the psychological treatment of pathological gambling: Long-term outcome. Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 24, 51–72.

Echeburúa, E., & Fernández-Montalvo, J. (2005). Psychological treatment of slot-machine pathological gambling: New perspectives. Journal of Gambling Studies, 21, 21–26.

Evans, L., & Delfabbro, P. H. (2005). Motivators for change and barriers to help-seeking in Australian problem gamblers. Journal of Gambling Studies, 21, 133–155.

Fukushima, H., & Hiraki, K. (2009). Whose loss is it? Human electrophysiological correlates of non-self reward processing. Social Neuroscience, 4, 261–275.

Grall-Bronnec, M., Wainstein, L., Guillou-Landréat, M., & Vénisse, J. (2009). Pathological gambling among seniors. Alcoologie et Addictologie, 31, 51–56.

Green, J., & Thorogood, N. (2009). Qualitative methods for health research (2nd ed.). London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Grimard, G., & Ladouceur, R. (2004). Intervention favoring control of gambling urge in players at risk of pathalogical gambling. Journal de Thérapie Comportementale et Cognitive, 14, 8–14.

Haworth, B. (2005). Longitudinal gambling study. In G.Coman (Ed.), Proceedings of the 15th annual conference of the national association for gambling studies (pp. 128–154), Alice Springs.

Helbig, S., & Fehm, L. (2004). Problems with homework in CBT: Rare exception or rather frequent? Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 32, 29–301.

Hodgins, D. C., & El-Guebaly, N. (2000). Natural and treatment-assisted recovery from gambling problems: A comparison of resolved and active gamblers. Addiction, 95, 777–789.

Jackson, A. C., Thomas, S. A., Thomason, N., Borrell, J., Crisp, B. R., Ho, W., et al. (2000). Longitudinal evaluation of the effectiveness of problem gambling counselling services, community education strategies and information products—Volume 2: Counselling interventions. Melbourne: Victorian Department of Human Services.

Jacobs, D. (1986). A general theory of addictions: A new theoretical model. Journal of Gambling Behavior, 2, 15–31.

Jimeneez-Murcia, S., Alvarez-Moya, E. M., Granero, R., Aymami, M. N., Gomez-Pena, M., Jaurrieta, N., et al. (2007). Cognitive-behavioral group treatment for pathological gambling: Analysis of effectiveness and predictors of therapy outcome. Psychotherapy Research, 17, 544–552.

Ladouceur, R., Gosselin, P., Laberge, M., & Blaszczynski, A. (2001). Dropouts in clinical research: Do results reported in the field of addiction reflect clinical reality? The Behavior Therapist, 24, 44–46.

Ladouceur, R., Sylvain, C., Boutin, C., Lachance, S., Doucet, C., & Leblond, J. (2003). Group therapy for pathological gamblers: A cognitive approach. Behavior Research and Therapy, 41, 587–596.

Lesieur, H. R., & Rothschild, J. (1989). Children of gamblers ananoymous members. Journal of Gambling Behavior, 5, 269–282.

McConaghy, N., Armstrong, M. S., Blaszczynski, A., & Allcock, C. (1983). Controlled comparison of aversive therapy and imaginal desensitisation in compulsive gambling. British Journal of Psychiatry, 142, 366–372.

McNeilly, D. P., & Burke, W. J. (2001). Gambling as a social activity of older adults. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 52, 19–28.

Melville, K. M., Casey, L. M., & Kavanagh, D. J. (2007). Psychological treatment dropout among pathological gamblers. Clinical Psychology Review, 27, 944–958.

Miller, N. V., & Currie, S. R. (2008). A Canadian population level analysis of the roles of irrational gambling cognitions and risky gambling practices as correlates of gambling intensity and pathological gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies, 24, 257–274.

Milton, S., Crino, R., Hunt, C., & Prosser, E. (2002). The effect of compliance improving interventions on the cognitive-behavioural treatment of pathological gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies, 18, 207–229.

Morasco, B. J., Weinstock, J., Ledgerwood, D. M., & Petry, N. M. (2007). Psychological factors that promote and inhibit pathological gambling. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 14, 208–217.

National Opinion Research Centre. (1999). Gambing impact and behavior study: Report to the national gambling impact study commission. Chicago: University of Chicago.

Oei, T. P. S., & Gordon, L. M. (2007). Psychosocial factors related to gambling abstinence and relapse in members of gamblers anonymous. Journal of Gambling Studies, 24, 91–105.

Petry, N. M. (2005). Stages of change in treatment-seeking pathological gamblers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 312–322.

Pope, C., Ziebland, S., & Mays, N. (2006). Analysing qualitative data. In C. Pope & N. Mays (Eds.), Qualitative research in health care (3rd ed., pp. 63–81). Carlton, VIC: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Preston, F. W., & Smith, R. W. (1985). Delabeling (sic) and relabeling in gamblers anonymous: Problems with transferring the alcoholics anonymous paradigm. Journal of Gambling Behavior, 1, 97–105.

Prochaska, J. O., DiClemente, C. C., & Norcross, J. C. (1992). In search of how people change. American Psychologist, 47, 1102–1114.

Productivity Commission. (2010). Gambling: Inquiry report. Retrieved from http://www.pc.gov.au/projects/inquiry/gambling-2009/report.

Pulford, J., Bellringer, M., Abbott, M., Clarke, D., Hodgins, D., & Williams, J. (2009). Barriers to help-seeking for a gambling problem: The experiences of gamblers who have sought specialist assistance and the perceptions of those who have not. Journal of Gambling Studies, 25, 33–48.

Robson, E., Edwards, J., Smith, G., & Colman, I. (2002). Gambling decisions: An early intervention program for problem gamblers. Journal of Gambling Studies, 18, 235–255.

Rugle, L., & Melamed, L. (1993). Neuropsychological assessment of attention problems in pathological gamblers. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 181, 107–112.

Scull, S., & Woolcock, G. (2005). Problem gambling in non-English speaking background communities in Queensland, Australia: A qualitative exploration. International Gambling Studies, 5, 29–44.

Splevins, K., Mireskandari, S., Claytin, K., & Blaszczynski, A. (2010). Prevalence of adolescent problem gambling, related harms and help-seeking behaviours among an Australian population. Journal of Gambling Studies, 26, 189–204.

Sprosten, K., Erens, B., & Orford, J. (2000). Gambling behaviour in Britain: Results from the British gambling prevalence survey. Melbourne: Australasian Gaming Council.

Stitt, B. G., Giacopassi, D., & Nichols, M. (2003). Gambling among older adults: A comparative analysis. Experimental Aging Research, 29, 189–203.

Sylvain, C., Ladouceur, R., & Boisvert, J. M. (1997). Cognitive and behavioral treatment of pathological gambling: A controlled study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65, 727–732.

Toneatto, T., & Ladouceur, R. (2003). Treatment of pathological gambling: A critical review of the literature. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 17, 284–292.

Walker, M. (2005). Problems in measuring the effectiveness of cognitive therapy for pathological gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies, 21, 81–92.

Weinstock, J., Whelan, J. P., & Meyers, A. (2008). College students’ gambling behavior: When does it become harmful? Journal of American College Health, 56, 513–521.

Welte, J., Barnes, G., Wieczorek, W., Tidwell, M. C., & Parker, J. (2001). Alcohol and gambling pathology among US adults: Prevalence, demographic patterns and comorbidity. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 62, 706–712.

Wood, R. T. A., & Griffiths, M. D. (2007). A qualitative investigation of problem gambling as an escape-based coping strategy. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 80, 107–125.

Acknowledgments

Ms Megan Bartlett (third year psychology student, Flinders University) for her assistance with data coding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dunn, K., Delfabbro, P. & Harvey, P. A Preliminary, Qualitative Exploration of the Influences Associated with Drop-Out from Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy for Problem Gambling: An Australian Perspective. J Gambl Stud 28, 253–272 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-011-9257-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-011-9257-x