Abstract

This study analyzed a sample of 920 lottery ads that were placed or played in Atlantic Canada from January 2005 to December 2006. A content analysis, involving quantitative and qualitative techniques, was conducted to examine the design features, exposure profiles and focal messages of these ads and to explore the connections between lottery advertising and consumer culture. We found that there was an “ethos of winning” in these commercials that provided the embedded words, signs, myths, and symbols surrounding lottery gambling and conveyed a powerful imagery of plentitude and certitude in a world of potential loss where there was little reference to the actual odds of winning. The tangible and emotional qualities in the ads were especially inviting to young people creating a positive orientation to wins, winning and winners, and lottery products that, in turn, reinforced this form of gambling as part of youthful consumption practices. We concluded that enticing people with the prospects of huge jackpots, attractive consumer goods and easy wins, showcasing top prize winners, and providing dubious depictions that winning is life-changing was narrow and misleading and exploited some of the factors associated with at-risk gambling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Advertising has been called the “the cave art” of contemporary society that makes consumption a top of mind behaviour. When it comes to gambling it is now common to hear or see dozens of ads a day enjoining people to “take a chance”, “share the dream”, “get in the game”, “live the thrill”, “become a millionaire”, and “go all in”. Many of these messages are read, seen or heard at a flash and are anticipated by audiences; we know that sooner or later we will see them in the course of watching a television show, reading a magazine, listening to the radio, or walking down the street (Chapman and Egger 1983, p. 168; Myers 1983, pp. 207–208). It is surprising then to find so few academic studies of advertising and gambling. This may be because the topic is difficult to research and bereft of reliable data to meet academic standards, or because it is sensitive to governments who often promote gambling through advertising making it seem attractive for the public purse even though it may be harmful to the public good.

However, based on studies conducted so far we do know that gambling advertising is ubiquitous and may be connected to problem gambling, higher sales and market shares, and adolescent gambling (Stinchfield and Winters 1998; Derevensky and Gupta 2001). On the one hand, Amey’s (2001) research demonstrated its pervasive reach. Of the 1,500 people he surveyed, 89% could remember seeing or hearing gambling advertising over a year period prior to the survey. Participation in gambling activities and recall of gambling advertising were linked. Those who gambled more than average reported seeing more gambling ads than others did while those who had few or no gambling activities were less likely to report having seen gambling advertisements (83% compared to 93% of those who had four or more activities). A Canadian study found that over 90% of respondents recalled seeing lottery ads and among them 39% claimed that because of this they were more likely to purchase lottery tickets (Felsher et al. 2004). Indeed, the constant exposure to gambling advertising has been indirectly connected to the onset of disordered gambling. Of 131 problem subjects interviewed in one American study, 46% reported that television, radio, and billboard advertisements were triggers for them to gamble (Grant and Won Kim 2001) and of 365 Canadian women gamblers who were interviewed about gambling problems 20% reported that exposure to ads was very or extremely important in creating urges or temptations to gamble (Boughton and Brewster 2002). Furthermore, the preliminary results from a recent Swedish study also found that advertising had a manifest impact for one category of problem gamblers triggering excessive play and blocking desistance from gambling while for two other categories of problem gamblers, advertising was not reported as a major cause of their disordered play. Nevertheless, problem gamblers overall were more likely than non-problem gamblers to recall seeing gambling ads and to remember gambling emotions, impulses, thoughts, and events connected to advertising exposure (Binde 2009b; Binde 2007a, pp. 174–176). On the other hand, another recent Swedish study found that the great majority of non problem and problem gamblers reported little or no advertising impact on their play habits and several other Canadian studies did not find that advertising was a trigger to problem gambling (Jonsson et al., as cited in Binde 2007a, pp. 171–172; Hodgins and el-Guebaly 2004; Hodgins and Peden 2005). Interestingly, and in line with studies of alcohol and tobacco advertising, Youn et al. (2000) found that subjects rated the influence of ads higher on others than on themselves. The mean score reported in their study on impact to self was 2.09 compared to 3.78 for impact on others and participants were more likely to be critical of lottery advertisements based on this third person effect than on perceived harm to self. So there are no compelling statistics on the direct impact of gambling ads on the prevalence of problem gambling, and in all likelihood advertising is one of several impacts including access to play, speed of play, and machine design characteristics (Binde 2009a, 2007a; Lee et al. 2008; Griffiths 2005). As Binde (2007a, p. 184) sums up, “on the basis of available factors, it can be inferred that advertising indeed increases the prevalence of problem gambling but its effect is less than those of other relevant factors”.

Econometric evidence evinces a similarly divided body of findings about advertising and gambling. On the one hand Zhang (2004, pp. 20–26) discovered that advertising impacted lottery sales directly in three American states; a 1% increase in ad spending had an increase in product sales of between 0.1% and 0.24%. On the other hand, Heiens (1999) and Mizerski et al. (2004) found no effect from advertising on either lottery sales or aggregate lottery market size once it had matured. There were differences, however, in the effects of advertising on market segments and market maturity: where there was competition advertising impacted size of market share, where there was monopolies advertising affected total sales, where there was market maturity ad impacts were generally low, and where there was market immaturity advertising had its greatest impact. While advertising campaigns may have been effective in increasing sales, introducing new gambling products and balancing the market share of competing products and companies, it is difficult to calibrate their impact on the overall volume of the market. There seem to be no studies that measure the extent to which advertising increases sales of gambling products and no studies that have demonstrated a concomitant increase in problem gambling as a result of higher sales (Binde 2007a, p. 170).

However, there is a more definitive reported relationship between youth gambling and advertising. Skinner et al. (2004, p. 264) found that society’s representation of gambling had a profound impact on youth, “affecting their personal characteristics, social relationships and early gambling experiences”. Korn et al. (2005) discovered that adolescents reported lottery advertisements as both familiar and engaging, particularly the Pro-Line Series and the Holiday Gift Paks and Promotions, because advertisers used buying factors such as humour to mobilize their appeals to youth and encourage them to participate in gambling activities. Derevensky and Gupta (2001) observed that commercial advertisements have a general effect on youth enticing them to purchase lottery tickets, and Woods and Griffiths (1998) discovered that the views youth held about gambling were radically changed by high levels of advertising. Indeed, Felsher et al. (2004) reported that youth were acutely aware of gambling ads on television, billboards and in the print media. Two out of five respondents said that their awareness of advertisements would encourage them to purchase lottery tickets. More recently, Derevensky et al. (2007) found that 42% of the adolescents they interviewed were influenced by the ads they saw or heard making them want to gamble, and Griffiths and Barnes (2008) discovered that 40% of a sample of British young adult on-line gamblers did so as a result of advertising. So there is mounting evidence that gambling advertisements in the media, along with point of sale advertising, celebrity endorsements, and the “gamblification of sports” by corporate sponsors are having a powerful effect on young peoples’ perceptions that gambling is an exciting, harmless form of entertainment (McMullan and Miller 2008a; Monaghan et al. 2008). As Landman and Petty (2000, p. 313) put it in the context of lottery gambling: “marketing stimulates and exploits counterfactual thinking to get consumers’ attention, change their thinking, and arouse their emotions, all in the service of inducing them to do what they perhaps would otherwise not do, that is buy lottery tickets”.

While these studies relating advertising to problem gambling, higher market volume, higher participation rates and adolescent gambling are important rationales to study the topic, our reason is less about the perceived impacts or effects on specific populations and more about the communication process underlying gambling advertising proper—the ad’s design, placement, timing, targeting, imaging, use of words and sounds, and content—and the ways in which ads convey both information about gambling (new products, jackpot sizes, special events) as well as preferred meanings where games are associated with values, lifestyles and beliefs to sell gambling to consumers. In line with contemporary advertising and marketing theory, we want to study gambling and advertising as a symbolic form of communication in its own right and explore how the circulation of meaning about gambling occurs in a discourse of share cultural codes that seeks to make it attractive to buyers (Sherry 1987). This means that we need to unpack sales pitches in order to understand how advertising as a core business practice shapes consumer identity in diverse ways that go beyond the functional value of buying bets. Thus it is important to ask different questions of advertising and its relationship to gambling: What is achieved by a gambling ad? How do ads function to persuade? What are the frequency, timing, placement and pattern of gambling advertising? What meanings, message and usages are prominent in gambling advertisements? Do gambling ads make use of the cultural capital of their audiences and deploy wider cultural referents to sell products? Does the design, exposure and content appeal to young people or resonate with factors that contribute to problem gambling?

To answer these questions we study gambling advertising, limiting our inquiries to radio, print, television and point of sale ads about lotteries in Atlantic Canada. We analyze a sample of 920 advertisements that were placed or played from January 2005 to December 2006 to examine the connections between the design and content of lottery advertisements and broader meanings of consumer culture. The paper is organized as follow: first we discuss the role of commercial advertising in consumer society and situate our study of lottery advertising in that context; then we explain our methods and data collection protocols; next we provide a detailed content analysis of the commercials and their exposure patterns presenting both quantitative and qualitative data; finally we discuss the dominant themes of lottery advertising in the wider context of what we call the “ethos of winning” surrounding contemporary forms of gambling and consumer culture.

Advertising and Consumer Culture

Advertisements aim to cause immediate impressions. Like modern myths they invoke responses that are swift and subconscious and like contemporary puzzles they evoke reactions that are cognitively challenging. In Pateman’s (1983, p. 201) words, ads are often amusing, intelligent and “visually pleasurable”. Advertising exists along a continuum bound by rhetoric and propaganda at either pole and employs tactics that are expressive and programmatic and range from the mildly persuasive to the nearly coercive. It is a form of communication that invests goods with meaning on the one hand and integrates these same products into a culture of buying on the other. Advertising strives to organize psychosocial processes of thought, emotion, perception, imagination and understanding and orders them through stories, ceremonies and symbols into an ethos that both shapes and reflects basic social realities (Sherry 1987, pp. 443–446; Pateman 1980, pp. 607–609). Every individual advertisement, therefore, is a ritual enactment of a larger phenomenon of advertising as a cultural communication system and should be studied as such. The formal properties of such rituals include repetition, acting, staging, stylization, and the affirmation of shared values. At a most basic level, ads sell social needs, desires and statuses to people. But the content of ads is almost always framed by knowledge of other cultural signs and symbols that already mean something to consumers. People often see themselves in the mirror of advertising because it is impossible to divorce advertising from what Goffman (1976) calls the wider world of cultural life that sets norms and ideals, defines significant events, and reinforces social practices and social values.

When it comes to contemporary forms of gambling, books, newspapers, magazines, films, television, the performing arts, music, radio, and the internet increasingly valorize them to their audiences as exciting, profitable and glitzy and connect them to a wider world of fame, entertainment and attractive living (Binde 2009a; McMullan and Miller 2008b; Griffiths 2005; Griffiths and Wood 2000). Newspapers and movies portray gambling much more frequently than in the past, and primarily through positive images in which fantastic wins, happy endings, and magicianly skill or luck predominate (Binde 2007b; Turner et al. 2007; McMullan and Mullen 2002). Quiz games linked to television programs now advertise gambling over the telephone to boost their ratings and provide consumers with interactive experiences involving lottery-like formats, virtual wagering and trivia competitions (Griffiths 2007). New information communication technologies and the computer permit continuous gambling on-line and allow spontaneous betting during sporting and cultural events such as wagering on whether some competitor will be eliminated from the latest round of American Idol. The future promises random mobile phone based promotional schemes where pre-recorded messages will offer gamblers betting vouchers to wager on pre-approved sites.

Indeed, gambling providers now promote their products with other consumer goods and services such as telecommunications, travel, leisure and entertainment, and associate their proceeds with public education, sport and cultural programs, and social welfare; schools, hospitals, churches and charities rely more and more on gambling to raise capital, thus extending the cultural reach and social legitimacy of gambling by embedding it further into the routines of everyday life (Korn 2007). Parents, for example, increasingly model gambling to their children by teaching them how to gamble, by financing their gambling activities and by buying gambling products for them as gifts, and young co-workers entering the workforce are encouraged to play daily and weekly draws hoping against all odds that they will dance the happy dance of the next millionaire (Derevensky et al. 2007; Mizerski et al. 2004). Indeed, in three recent Canadian studies, gambling was not even thought of as risky behaviour; it was ranked below hitchhiking alone, cheating on a test, dating on the internet, shoplifting and skipping work, and regarded as a common feature of everyday life like drinking, smoking and driving an automobile (Derevensky et al. 2007; D-Code Inc 2006, pp. 11–12; Korn et al. 2005, p. 23).

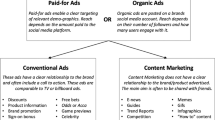

So gambling ads, like other types of advertisements, are designed and coloured by knowledge of other cultural texts, images, practices and institutions where a rich meta-language of pleasure, sport, sexuality, and youthfulness operate as referent systems to invest ads with meaning, significance and credibility. Alcohol and tobacco advertising and branding, for example, have been especially crafted to mirror dominant representations of youth lifestyles as selling points. McCreanor et al. (2005, p. 257) found that beer and vodka advertisers tried to sell their products as inherent to adolescent culture by sponsoring fashion events, popular dances and creative competitions on their websites. Gray et al. (1997) revealed that fashion spreads in magazines in Britain in the 1990s played to the reader by portraying body and facial “looks” which tapped into and reflected back the mythology which young people identified with and aspired to—the mythology of being “noticeable” and “someone” as a result of smoking cigarettes. Marlow (2001:42–43) discovered that cigarette advertising on billboards in the United States capitalized on the theme of youthful dissent and escapism. Joe Camel, the ultra cool guy was the epitome of “attitude” in the ads, an urban expression of choice and defiance against middle class values that seduced teens into smoking, even if it harmed them. He was expressed in his own youthful rebellion as simply above all sensible advice. Taylor (2000:339–344) also reported that visual codes, spoken texts, and written words in ads were entwined with other forms of cultural capital to sell liquor to youth in the United Kingdom. Perfume and designer drinks, for example, were promoted through coded references to club culture (dancing, music and sexuality, etc.) and to a wider secondary language of pleasure that drew upon familiar words, signs and symbols of drug culture, connected these products to their cultural referents, and sold alcohol and cosmetics back to consumers as versions of their own needs and desires. Walsh and Gentile (2007, pp. 5–8) noted that “frogs sold beer” in the United States. By using emotional messaging and targeting consumers with humor, heroes and repetitive exposure, they discovered that these ads worked best when they slipped underneath the radar of awareness when consumers were not conscious that they were being affected by persuasion techniques. Korn et al. (2005); Derevensky et al. (2007) and McMullan and Miller (2008a) found this to be true with gambling advertising in Canada. Ads, they say, were perceived as reasonable, exciting and natural because thinking about the products was linked to cultural signifiers of youth culture—instant fame, quick wealth and an exciting life. Indeed a recent Swedish study discovered that this focus on “winning, fun and excitement” in lottery ads was embedded in broader cultural messages such as hope, freedom, and self-expression which emboldened the ad’s appeal and anchored its attractiveness (Binde 2009a). From this cultural perspective, advertising is increasingly complex and artful requiring careful study of how they do what they do and how they create metaphors for viewers and listeners long after the ads have been aired or printed. This requires content analyzing advertisements to assess their messaging and claims in a systematic study (Griffiths 2005, p. 20).

Methodology

Content analysis and textual analysis is utilized to explore the selling of lottery gambling and its accessibility to the public. Content analysis is used because it is a good method of studying “communications in a systematic, objective, and quantitative manner for the purpose of measuring certain message variables” (Dominick 1978, pp. 106–107) and because it is well suited to explore the classic questions of communications research: “who says what, to whom, why, how and with what effect” (Maxfield and Babbie 2001, p. 329). Content analysis is a relatively unobtrusive way of analyzing social relations quantitatively which when combined with qualitative textual analysis allows for deeper patterns of meaning and tonality to be explored and analyzed (Coffey and Atkinson 1996, p. 62; Manning and Cullum-Swan 1994, p. 464; Neuman 2003, p. 313; Riffe and Freitag 1997). On the one hand, we study the sounds, images and texts of lottery advertisements in print, radio and television mediums. On the other hand, we analyze the wider cultural context of the ads and their signifying capacity for registering and reregistering persuasive messages in commercials (Banks 2001; Jones 1996; Sturken and Cartwright 2001). As van Dijk (1993, p. 254) puts it, “content analysis shows how managing the minds of others is essentially a function of text and talk.”

In addition, textual analysis is deployed as a qualitative tool to illustrate in more detail the persuasion techniques used (a) to entice and hold consumer attention, such as humour, the promotion of real winners, and message repetition, (b) to appeal to motives and preferences such as becoming rich, doing something exciting, and displaying talent in predicting the outcomes of sporting events, and (c) to try to convince buyers to choose particular products over others and establish unique brands by advertising a lottery ticket as a ticket to a new home or a scratch card game as an opportunity for personal growth and transformation. This qualitative analysis was deployed to compliment the quantitative analysis and allowed us to explore the symbols, signs and meanings attached to the ads, and to show how messages were designed to interact with and persuade viewing and listening audiences to gamble (Binde 2009a; Berger 2000, p. 40).

The data used in this study was provided by the Atlantic Lottery Corporation and consisted of two important features: a complete two-year sample of 920 lottery ads, and a database connected to 114,538 placements for 157 of these ads. Point of sale ads were not included in the database as they appeared mostly on the premises of retail outlets and were not tracked by the lottery corporation. We designed our study following research that employed content analyses to study alcohol, tobacco and gambling advertising (Gulas and Weinberger 2006; Korn et al. 2005; Tellis 2004; Agres et al. 1990; Dejong and Hoffman 2000; Chen et al. 2005). These studies provided insight into variables important to product appeal, design and likeability. Each commercial was named and coded for the following variables: (1) Intended Audience: consisted of four types of audience: gender, age, race/ethnicity, and gambling status. Gender included males, females, both males and females and neither. Males were coded when the overall majority or main characters were male, when images were directed toward male oriented interests, or when the main storyline focused on males. Females were coded when the overall majority or main characters were female, when images were directed toward female oriented interests, or when the main storyline focused on females. Both males and females were coded when the amount of time in the advertisements and the main spokespersons were equally divided between males and females. The absence of males and females were also coded. Age included groups who appeared to be between the ages of 13–18, 19–35, 36–60, and over 60. Race/ethnicity was coded when the overall majority or main characters appeared to be members of visible ethnic communities. Gambling status included people learning to gamble and/or established gamblers in the ads; (2) Word Count: consisted of the number of words spoken within the commercial; (3) Advertiser: indicated the name or source of the advertiser; (4) Voiceover: related to the presence and gender of the broadcast voice in the ads; (5) Number of Frames: consisted of the number of camera frames used per advertisement; (6) Colour Scheme: referred to bright (vivid, loud), dark (shady, gloomy), contrasting (bright and dark), and neutral (muted, dull, soft) displays of colour within the ads; (7) Camera Position: related to long shots (environment), medium shots (character and environment), and close-up shots (character or objects) in the ads; (8) Pace: indicated slow, fast, and the combination of slow and fast effects based on camera frames, voiceovers, music and graphics; (9) Appeal: referred to the use of amusement (humour, happiness) and excitement (anticipation, hope) in the ads; (10) Vocabulary: referred to intellectual specialized words or phrases; conversational discourses, jargon or cultural references; neutral terms neither specialized or conversational; and no spoken words; (11) Sound: consisted of ambient naturally occurring sounds, electronically enhanced and manipulated sounds, and music; (12) Products: referred to the type of gambling advertised (GameDay, Lotto 649, PayDay, Super 7, Scratch ‘N Win, Bucko, Atlantic 49, Corporate Ads, Video Lottery Terminals, Bingo, ProLine); (13) Odds of winning: were coded as absent or present in the advertisements; (14) Sexualized imagery: referred to eroticized portrayals of men or women, including acts, gestures, or clothing that accentuated objectification along sexual lines; and (15) Theme: referred to focal narratives in the gambling advertisement such as winning, normalization, escapism, and community benefits.

The authors then developed a codebook along with operational definitions of all variables. Both authors independently viewed each ad twice, resulting in 100% agreement on all dichotomous variables. When a variable could not be so sharply distinguished, as in some thematic messages, both authors viewed each ad several more times until consensus was reached. As noted, the lottery database contained exposure variables such as information about products (i.e. Lotto 649, Bucko), mediums (i.e. print, television, radio), programs spots related to television only (i.e. CBC News, Jeopardy, Late Night Movies), markets (i.e. Halifax, St. John, Truro), geographical regions (i.e. Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Newfoundland), vendors (i.e. Cape Breton Post, Halifax Chronicle Herald, Atlantic Television Network), and air/print dates for each ad. This database allowed us to connect the design and content features of the advertisements to a broader framework of convenience of play such as how many times the ads showed, the days and weeks of the month they were placed, the types of programming they were associated with, and so on. A caveat, however, is called for. Content analysis is best at revealing the preferred messages of the senders of the ads and at uncovering the design and strategy of the communication act. It does not evaluate how the messages are received, nor account for how attitudes, beliefs, or behaviours are affected. These tasks are best undertaken by interview studies or longitudinal surveys.

Results

The Importance of Advertising Lottery Gambling

Provincial governments in Canada are in a monopoly position as suppliers of lottery products. They cannot increase sales by increasing market share as most businesses do, so they rely on enlarging the size of the gambling market itself by increasing either the player base (more users) or increasing the overall wagering of existing consumers (more usage) or both. Typically this has been done by introducing new games, stimulating crossover play, packaging gambling products as attractive consumer options, encouraging consumption via direct communication methods such as mail-outs and online web incentives, and targeting specific market segments based on demographics or psychographics (Clotfelter and Cook 1989, pp. 187–189). For example, Playsphere, the online service for lotto draws and sport betting, was introduced in 2005 to attract new players. Over and Under, a fixed prize game, was changed to an odds based game to increase player usage. Atlantic PayDay was created to provide “the chance to dream of an extra $2,000 to spend every 2 weeks for 20 years”, and Atlantic 49 was reconfigured as a regional draw that could be purchased on its own or with Lotto 649 tickets (Atlantic Lottery Corporation 2004–2005, p. 5). With limited room to maneuver, provincial gambling providers also increased the number of large weekly jackpot lotteries (i.e. from Lotto 649 to Super 7), created new frequent daily draws (i.e. Bucko), varied the ticket prices (i.e. from loonies to toonies), increased the jackpot sizes for passive lottery games, and diversified the expected value of prizes for sports betting in order to attract new consumers, increase the betting values of existing players and stay competitive with other jurisdictions such as the internet. In 2006, for example, the lottery corporation introduced proposition wagering to ProLine products permitting consumers to bet on game related matters (i.e. the player with the most pass receptions in a football game) as well as on the end results, created a new Superstar Linked Bingo product that connected multiple bingo halls to larger jackpots for customers, and added several interactive games to their online system (Atlantic Lottery Corporation 2005/2006, pp. 7–9). Beyond these basic principles of product and price, the lottery provider relied on regular promotion and advertising to launch new products, introduce corporate sponsors, target seasonal buying, display information on wins and winners, and highlight the benefits of lotteries to media outlets and the public. Over 8 million dollars ($8,353,623) was spent on lottery advertising in 2005 and 2006 (exclusive of point of sale expenditures which were not known). The media spend amounted to $4,761,394 for television, $1,821,793 for print (including outdoor signage and billboards), $1,464,333 for radio, and $81,973 for web ads, and an additional $224,130 for media buying fees and resulted in 114,538 lottery ad placements over the 2 years.

Mediums, Exposure and Convenience

The dominant medium of advertising for lotteries in Atlantic Canada was the radio. Of all advertisements placed 79,478, or about 70% (69.4%), aired on 80 radio stations. These radio stations included hard rock, light rock, oldies, country, easy listening, and talk radio. The majority of ads were broadcast in New Brunswick (N = 29,035) and Nova Scotia (N = 26,537), followed by Newfoundland (N = 14,469) and PEI (N = 9,437). Of the 33 towns and cities where the radio ads played, Halifax was the site of 10,909 radio ad airings (13.7%), almost double the volume in any other community. Over four out of five (86.8%) radio ads were 15 s in length, while 13% aired for 30 s. The average number of ads run on radio per month was 3,311, or about 110 a day, but the pattern of placements was erratic and ranged from a low of 294 radio spots in September 2005 to a high of 6,919 spots in April 2006.

The lottery corporation also regularly utilized television in order to advertise their products. Of all ad placements 30,928, or about 27%, aired on 18 television stations in the Atlantic Provinces. Four of these stations broadcast to all Atlantic Provinces and accounted for almost 60% (N = 17,481) of the ads shown. An additional 30% were aired solely in Newfoundland (N = 9,378), 10% in New Brunswick (N = 3,105) and 3.1% in Nova Scotia (N = 964), respectively. Two-thirds of the television ads were 30 s in duration; one-quarter were 15 s, and about 5% were 5, 10, or 60 s long. The frequency of television ad placement ranged from a low of 590 television spots in November 2005 to a high of 1,886 spots in July 2005, averaging 1,288 ads per month or about 43 a day. They ran on diverse television programs such as News Programs (29.5%), Dramas (10%), Talk Shows (9.2%) and Soap Operas (9.1%) to name the more prominent program types.

The lottery corporation used the print media as a source for advertising in about 4% of their overall placements (3.6%). Of all ad placements, 4,132 appeared in print formats such as newspapers, outdoor posters and magazines. Thirty-three vendors ran these ads, which for the most part, consisted of local Atlantic newspapers such as the Truro Daily News or the Saint John Telegraph Journal. One thousand six hundred and thirty-four of the ads ran in Nova Scotia (39.5%), 1,132 in New Brunswick (27.4%), 553 in Newfoundland (13%), 422 in PEI (10.2%) and 388 in all jurisdictions (9.4%). The frequency per month was as low as 19 and as high as 329 with an average of 172, or about 6 ads a day. The low rate of ad placement occurred between June and September 2005, while placements were much higher between October 2005 and June 2006.

In addition, there were thousands of point of sale displays in approximately 5,500 retail outlets in Atlantic Canada; about 1,200 of these outlets were in Nova Scotia (Atlantic Lottery Corporation 2005/2006). Four hundred and twenty-nine liquor licensed establishments in the province also offered video lottery terminal (VLT) gambling in bars, lounges, cabarets, legions, golf and curling clubs, and on First Nation reserve lands (Atlantic Lottery Corporation 2006/2007). Advertisements of VLTs were “limited to the interior of the approved premises” (Nova Scotia 2007) and to features of the device itself—names of the machine games, speed, sight and sound of the devices, and fast paced rewards and reinforcements—all of which were important in forming impressions about the product (see Zangeneh et al. (2008) for this type of study). Taken together, the state sponsored lottery advertised heavily on billboards and newspapers, and especially on radio and television, and encouraged widespread accessibility so that their ads were omnipresent and difficult to miss in most retail outlets. As Griffiths (2005, p. 17) observes, “lotteries are more salient than other forms of gambling that do not have the same freedom to advertise”.

Products

The lottery corporation advertised four types of gambling products on radio: Game Day, Lotto 649, PayDay and Super 7. The 40,604 Lotto 649 radio ads (51.1%) and 32,088 Super 7 ads (40.4%) accounted for over 90% of all radio advertisement placements. Many of the radio ads were broadcast repeatedly and many were duplicates in form and content except for the jackpot amounts which varied from draw to draw. Altogether we analyzed 22 distinct radio ads that played thousands of times over the 2-year period. Eight types of lottery products were also advertised on television. Of the 30,928 television ads, 7,864 were for Scratch ‘N Win tickets (25.4%), 5,073 were for PayDay (16.4%), 4,106 were for Bucko (13.3%), 4,118 were for Lotto 649 (13.3%), 3,781 were for Super 7 (12.2%), 3,437 were for Corporate promotions (11.1%), 1,506 were for Atlantic 49 (4.9%), and 1,043 were for GameDay (3.4%). After removing duplicates we analyzed 89 distinct television ads that played many times a day in 2005 and 2006. Five types of gambling products were advertised in print: Bucko, Lotto 649, Scratch ‘N Win, Super 7, and Corporate Ads. The 2,000 Super 7 (48.4%) and 1,305 Lotto 649 ads (31.6%) accounted for 80% of the 4,132 print ad placements. After removing duplicates we analyzed 46 distinct print ads that were repeatedly circulated to local audiences. We also examined 763 point of sale ads, including digital signs, posters, banners, promotional items, tickets, window signs, winner announcements, and floor and counter displays related to traditional ticket and VLT products that were readily seen by consumers as they bought food and gas, visited malls and bars, or filled prescriptions. The product name most frequently highlighted in point of sale ads was Scratch ‘N Win. Forty-seven percent or 356 of the ads were for this product followed by ProLine/GameDay at 11%, Bingo at 7% and Lotto 649 at 5.5%.

Image, Tone and Text

The lottery commercials employed several design techniques to encourage lottery play. The use of colour, for example, was important in attracting and holding audience attention. All 89 television ads utilized bright colour schemes and avoided dark or even muted colours in their presentational style. Vivid red, yellow, blue and green hues were depicted in homes and cottages, on the streets, on clothing, and on product logos as if to tell and retell the viewer that gambling was an upbeat, fun-filled consumer activity that was attractive and exciting. Two of three of the print ads (63%) utilized vivacious colours. Scratch ‘N Win commercials deployed contrasting colours to highlight the faces of the scratch tickets: blue tickets on red backgrounds, orange tickets on black backgrounds and green and red colours on counter posing backgrounds. Colour was also prominent in point of sale ads where it was often used to differentiate lottery products. Bingo ads, for instance, were framed in pink, mauve and purple, whereas Pro-Line ads were consistently bright green, allowing customers to instantly recognize specific products. The window signs for Lotto 649 and Super 7 featured blue backgrounds with yellow lettering on top that provided the jackpot sizes: “$35 MILLION”, or “BIGGEST EVER!” dominated the posters and attracted the sightlines. Other ads portrayed the lottery logo in order to inform audiences that certain products were available at particular outlets at particular times. Even the ballot box headers, ticket trays, merchandise holders, play-stands and sidewalk signs were strategic eye-catching advertisements designed to attract attention and incite purchases in high viewing spaces inside and outside retail outlets.

Sound was another important design feature in the ads. Over 80% of the television ads (N = 72) utilized some form of music in their messages and about one-third also used ambient sounds (N = 32) such as rolling thunder, loud laughter or happy crowds to appeal to audiences. Several ads deployed electronically enhanced sounds, where fireworks, for example, were magnified to contextualize the drama and excitement of gambling to viewers. All radio ads featured music in their messages. For example, Set for Life ads played the song “Hey, big spender” after asking the question “If you won Set for Life what would you do?”. Some ads played hard-paced music throughout the entire commercial while others played it strategically to accompany the announcements of big pots or to sharpen the listening audience’s attention concerning the introduction of new products or the diversity of prizes. Fully half of the radio ads (N = 11) displayed ambient sounds such as cash registers and cheering crowds to set feel good moods, encourage participation, and signal the fun value of lottery gambling, especially winning. Voiceovers were also important in the sales pitches. Radio voiceovers were insistent and enthusiastic in their persuasion style providing basic information to listeners while simultaneously encouraging wagering as thrilling and rewarding. The majority of voiceovers were male: 80% of the radio ads utilized male voiceovers (N = 18) to signal their products to their audiences. In addition to voiceovers, the voices of male actors (83%) were utilized much more frequently than females in the radio ads. For example, not one of the 10 GameDay ads used a female voice to sell the product. Similarly, male voiceovers (N = 32) in television ads were deployed almost four times more than females (N = 8).

Human images were important in television and print ads. On television, 240 people (actors, models and real winners) were portrayed and two of three (67.4%) depicted appeared to be between the ages 19 and 35. The overwhelming majority were Caucasians (92.9%) and males (N = 141) were in the ads much more frequently than females (N = 99). Males were the intended audience in 37 of the ads compared to 20 for females and 20 for both genders. Over 40% (41%) of the print ads included depictions of human images, especially those that signified gambling as a community benefit. These ads depicted happy winners on one side of the ad, and new community development successes such as road repair on the other. More images of females (N = 14) than males (N = 7) were presented in print, and all were Caucasian. By contrast, point of sale ads did not typically deploy human images; only 15% (N = 117) of these advertisements contained facial or body images in their messaging.

Lottery ads also deployed particular forms of speech to pitch their products. Two-thirds of the radio ads (N = 15) were conversational in character and used casual, everyday interactive dialogues between models or winners to emphasize the familiar and cooperative character of lottery play. One-third of the radio ads (N = 7) employed neutral linguistic tropes to announce draws, or reveal that a new product such as the “Hot 7 Series of tickets” was available to consumers. Over half the television ads (N = 48) used a language style that was conversational, a third deployed a neutral discourse (N = 28) and 15% eschewed speech altogether (N = 13). Conversational language was informal and emotive, and included vernacular phrases, such as “People are gonna be winnin’ everyday”, “Lay it on me” and “Great view, huh?” which were designed to index the commonplace character of the games and their popular appeals. Winners and actors were portrayed as wise, friendly and trustworthy. They understood and enjoyed lottery gambling and viewers were encouraged to appreciate their knowledge, identify with their good fortune, feel the excitement of their success and ultimately emulate them. The words and phrases used in neutral speech, by contrast, connoted a discourse that downplayed the sentimental and the sensational. Story telling in these ads was mundane and unremarkable. It used matter of fact diction to remind audiences that gambling was personally rewarding and socially beneficial. “Congratulations to the Oxfords, Atlantic 49’s recent top prize winners” or “One hundred percent of the profits go back to Atlantic Canadians” were exemplars of this approach to advertising. Some ads did not combine speech or texts with images and relied instead on music and non-verbal cues to communicate their messages. Several Scratch ‘N Win ads, for example, portrayed winners holding signs that announced their names and winnings in the first frame, while the next frame revealed the benefits of their winnings to viewers: new homes, cars, motorcycles, hot tubs and holidays. The techniques of persuasion here allowed the commodities to speak for themselves, as if to say to the audience if you want me scratch a ticket now!

Pace was an essential ad feature. Over two-thirds of the 22 radio ads were fast paced in design. Breathless announcers and grandiose music combined to create an “edge of your seat” listening environment. In the ad Football 4, for example, a sports announcer actor enthusiastically proclaimed a gambling scenario as equivalent to scoring a touchdown suggesting the winning consequences of a well-timed wager (“It’s a pass! He’s got it! He—could—go—all—the—way!”). In contrast, about 30% of the radio ads (N = 7) evinced an unhurried almost pacific pace to selling lotteries. The Super 7 ads often used calming cadences and soft music to communicate the laid back lifestyle after lotto wins. Two-thirds of the television commercials were also slow paced in character (N = 57). Casual voiceovers, relaxed background scenarios, and the use of direct personal narration indexed gambling as a thoughtful cerebral event where happy consequences result from hopeful dreaming. Some television ads, about a quarter of them (N = 21), however, were quick paced. By contrast, they employed rapid frame changes, continuous movement, and intense music as selling points. For example, Pro-Line ads often relied on edgy graphics, dramatic music and flashing colours to attract and hold viewers’ attention. The rapidly changing sounds and frames mirrored and even parodied the high energy activities associated with live sports events. The images and sounds of players and fans were interpellated as selling techniques to constitute the gambler as an athlete-like figure preoccupied with overcoming adversity and uncertainty. In one ad, Basketball, two fans were shown with “Go Team” and “#1” painted on their faces in their respective team colours. The ad ends by provocatively asking the audience “How good is your game?” referring, of course, to their customers’ abilities to overcome uncertainty and pick winners while sports betting.

Some ads balanced commercial selling with responsible gambling messages. Responsible disclaimers, such as “Must be legal age of majority”, were present in 45% (N = 10) of the radio ads but two out of three (N = 31) print ads did not include a responsible gambling message and one-third (N = 15) that did emphasize the theme: “Know your limit. Play within it” but in small print at the bottom of the ads. Over 80% of the television ads (N = 74), however, contained responsible gambling messages but they were almost always less than 2 s in duration, and presented in small font on the bottom of the last frame of the ad. Information on the odds of winning appeared in none of the radio ads and in only four of the television commercials, and in a decidedly confusing manner. For example, scratch tickets marketed at Christmas time guaranteed a “winner in every pack” without indicating the prize, and a frequently played Lotto 649 ad displayed a man holding an umbrella that was suddenly struck with lightning whereupon a voiceover whimsically intoned: “Think winning the Lotto 649 jackpot is about as likely as being struck by lightning? Meet the latest luck struck winners.” These texts and images intimated that “You could be the next winner”, and ignored or downplayed the true probabilities of winning large jackpots. Responsible gambling themes were also present in about half of the 763 point of sale advertisement materials (N = 392). These warnings typically stated the legal rules of age participation, instructed retailers to “Check I.D.” and not to “sell to minors”, or provided general advice to players such as “Don’t gamble your future”, or practice “Responsible Gambling – It’s your best bet”. Most of these caveats, however, were also fixed in small lettering at the bottom of the ads, or in the case of tickets, printed on the backside where they were less visible.

Appeals and Messages

A large number of lottery adverts relied on emotions to sell gambling products. All 22 radio ads coded some form of excitement in the verbal discourse primarily by dramatizing the promise of winning. The voices in the ads heralded the likelihood of successful outcomes: “Play Atlantic PayDay every Thursday and you could win it” or “A new shot at winning every week” were exemplars of the excitement enticement. The “thrill” appeal was also prominently connoted in about 7 of 10 television ads (N = 64). Winners were portrayed as delirious with delight. They shouted out their pleasure in jubilation, “Yippee, yippee, yippee”, or sang “You’re in the money, you’re in the money”. Even winning a free scratch card was enough to enjoin exhilaration. “I was really, really excited. So excited” conveyed the message that insta-pick arousal was quick and pleasurable, so “keep on scratching!”. Other commercials mobilized excitement appeals by displaying actors and real winners dancing, joking and laughing with the audience. Over half of the print ads (N = 25) also exuded excitement as enticement. Lotto 649 and Super 7 ads relied on big jackpots to arouse consumer purchasing. Boldly printed ads were framed around prominent colourful millionaire dollar signage which completely dominated the ad setting. The large black lettering and white background encouraged viewers to consider the “Wow” of the win. Some Scratch ‘N Win ads used non-monetary prizes to communicate the excitement of play in the ads: “Win a trip to a Nascar race of your choice” or win a “car bonus”. Still other ads, like Bucko! matched colourful catchy phrases and icons with amusing and dramatic images to simulate the excitement appeal of wagering.

Humour was also used in the ads. Approximately one in four radio ads (N = 6) used amusing stories to try to persuade the audience to gamble. One voiceover in the PayDay ad Backbreaking teased the listener by portraying lottery winners as over burdened by success: “It must be backbreaking picking up all those cheques from the mailbox”, the ad ironically remarked to listeners. Other PayDay ads were parodies of actual employment ads, except they warned the audience that winning was hard work. Amusement was also present in three-quarters of the television commercials (N = 65). It was often combined with irony to encourage win/wealth scenarios around gambling. Messages such as “Some people say that money doesn’t buy happiness. That’s just because they don’t know where to shop”, or “You know, sometimes I do think that it’s too much money for one person. But we’re two. Oh, yeah, we’re two”, and “being a multi-millionaire also has its downsides. Like what for instance?” subtly anticipated and wryly subverted ideas that gambling was a controversial form of consumption associated with excess, hedonism or loss. About one in five print ads also mobilized humour (N = 8) to make gambling appealing to viewers. Bucko ads, for example, used puns and whimsy to promote daily lottery play. Amusing texts were placed beside the Bucko icon and designed to invite the reader to ponder the following quips: “Play me before I’m spent”, “You could turn one of me into 20,000 of me. Lucky you”, or “More winners than I can shake my stick at”. Different facial expressions were drawn on the Bucko character to simulate surprise, suspense and delight, and add to the amusement value of the ads.

Several focal themes emerged in the ads. First, winning was always highlighted. All radio ads dramatized jackpots, winning prizes, and free lottery tickets in their messages. Super 7 ads regularly promoted the “incredible” jackpot worth millions, while Set for Life ads regularly offered free tickets to radio callers. Other commercials encouraged audiences to “imagine” the prizes to be won. All the GameDay ads exhorted players to “Win the Pot” and The Lotto 649 ads glamourized the total sum of winnings: “the next Lotto 649 jackpot is estimated to be “22 million dollars!” so do not “forget to play!” and do not “miss the next draw”! Super 7 ads asked listeners to ponder a simple question: “What if?” and presented scenarios showing how lives changed after lotto wins, while Scratch ‘N Win ads emphasized participatory fantasies; “share your dreams of winning” and “What would you do?” were the thematic anchors enjoining listeners to consider new opportunities in life and share them with unknown thousands. The ads Hot 7 One and Set For Life, for example, encouraged daily dialogue between consumers and radio announcers on air: “Call in and tell us the seven things you would do if you won 7,777 dollars with a new Hot 7 series of tickets from Atlantic Lottery”, or “We’ll start a story and give you 50 s to finish it, and for playing you’ll receive five Set for Life tickets. So let us hear your fantasies on radio!”. Several radio ads also used sports referents to magnify the theme of winning. “GameDay Pick ‘em Pool” ads highlighted roaring crowds, ambient sounds like the “hut! Hut!” of football players and the dramatic discourse of play by play announcers to connect the thrill of gambling with the excitement of sport events. Commercials repeatedly deployed the words “we have a winner”, “one win away” and “winning every week”, and connected this message to potential fame; gamblers like athletes were “on the road to glory” and sports betting was “one more face off”, or “a touchdown away” from a win.

There was also a strong emphasis on big jackpots and wishful thinking in about 80% of the television ads (N = 70). Scratch ‘N Win ads, for example, highlighted the fulfillment of dreams. How Many Weeks showed a young couple in a buying frenzy except that goods were priced in weeks not dollars. A television set sold for “seven weeks plus tax” and a house sold for “15 or 16 weeks down payment at about a week a month”. This new currency converter provoked the question: “Hey, how would you spend a week?” leaving the audience to imagine what their life would be like were they to suddenly “scratch ‘n win”. Another ad for Lotto 649, Lake Cottage Gifts, mobilized family values as a persuasive tool to endorse “Bigger jackpot. Bigger Possibilities!” The ad opens with a summer scene. A mother and father have just bought a new cottage on a scenic lake. Their two admiring children indicate that they will visit every weekend. They are then handed keys to two beautiful waterfront cottages of their own. The parents, children, and grandchildren embrace in celebration as their family dreams have been realized. The ad ends with the tagline: “Everybody’s got a dream!”.

Winning narratives were present in almost all of the print ads as well (N = 44). Again the emphasis was on dramatizing jackpot size to entice investment. Some ads included a personal touch and emphasized what winners could do with their prizes: “Scratch ‘N Celebrate”, “Scratch ‘N Renovate”, Scratch ‘N Get a Big Screen”, Scratch ‘N Go Shopping” and “Scratch ‘N Get Away” and displayed the tagline “For Everyone Who Likes to Win”. Even when big jackpots were not highlighted, winning was still stressed. The Bucko ads, for example, assured readers that they could “Win on any day ending in ‘y’”, and the Christmas for Life ads declared “You could win”. Without indicating the prizes, they invited the reader to interact with messages, imagine the jackpot sizes and hope for the delightful consumption consequences.

The narrative of “winning”, “being a winner”, or “winning changed your life” appeared in almost 90% of the point of sale ads (N = 680). Outlets typically received and displayed posters with large jackpots, the names of previous winners, and catchy and provocative phrases such as “instant millionaire”, or “we all win” as triggers to sell lottery products. Large billboards aided in disseminating information about cash prizes and retail stores circulated these messages through sidewalk signs and clipboards for passer-bys to see. One sign aptly summed up the preferred message: “Winning Numbers Available Here”! Jackpots and prizes were made even more attractive at the point of sale venues because they were often offered in conjunction with other corporate sponsors or tied to corporate reward programs so as to entice consumers to purchase gambling products to obtain related bonuses or benefits such as free gasoline for a year (PayDay), or luxury getaway packages to exotic places such as the Caribbean (Scratch ‘N Win). Gambling signs and symbols in the form of branded merchandise entered homes (clothing, furniture coasters, and mugs), workplaces (desk calendars, mouse pads), and leisure spaces (playing cards, coolers) and the add-on giveaways were especially appealing to consumers who wanted immediate benefits from playing lotteries and to others who might otherwise be unfamiliar with gambling, such as the successful, inner-directed socially conscious persons typically found in psychographic studies of values and lifestyles (Biener and Siegel 2000, p. 400; Clotfelter and Cook 1989).

A second theme frequently found in advertising was that gambling was a normal and rational consumer product choice. Over 90% (90.9%) of the radio ads presented gambling as a natural, everyday activity. The endless promotion of draws and tickets ritualized lotteries as consumer events not unlike buying groceries or shopping for clothes. Radio stations held contests weekday mornings where Scratch ‘N Win tickets were the prizes. The ad, Perks, for example, linked lottery products to a rock radio station that further routinized gambling. “Every morning we’re giving away PayDay tickets for a year”, the dawn patrol radio announcers advised, “for your chance to win a dream Pay Day of 20,000 dollars cash, enter our PayDay perks contest”. The theme of normalization was also evident in about 60% of the television commercials (N = 56). Bucko ads epitomized this theme best. Some ads portrayed Bucko as a local guy hanging about lottery kiosks and retail stores encouraging customers to buy a bet. Others portrayed him as a famous personality—a star on the walk of fame, a talk show guest, a soap opera figure, and a television actor who reminded viewers that “People play Bucko here everyday”, “You can win all these prizes everyday”, and “Give a loonie a chance—play Bucko any day for just a buck”. Still other ads naturalized winners suggesting that gambling was predictable as well as daily. In Guess How Many, the Bucko icon is positioned in front of a progressive jackpot ticker and asks the viewer “Guess how many Bucko winners we’ve had so far?” The counter then sucks Bucko into its mechanism, spins him around and spits him out. When the counter stops on the final number of winners, 2,202,063, a dizzy Bucko announces “Wow, that’s a lot of winners! Give a loonie a chance”. Finally, other ads partnered with media outlets to normalize gambling’s reach. Television news anchors, for example, announced several “PayDay Perks” contests. Viewers were invited to call in their “funny work stories” to the television station in order to qualify for a dream salary of $2000 every two weeks for a year. These contests were eerily reminiscent of the lottery provider’s actual PayDay game which offered dream salaries of $2000 every 2 weeks for 20 years. News people, whom viewers trusted to tell them the truth about world affairs, delivered the message that gambling was an acceptable and rewarding activity without providing any reservations concerning the associated costs or problems. Half of the print ads also put gambling into a language that made it seem everyday and expected (N = 23). Lotto 649 and Super 7 ads, for example, reminded the audience that “Friday” and “Saturday” jackpots were weekly events, while others like ads for Bucko and Scratch ‘N Win told viewers that gambling was minute by minute and day by day endeavors. Still other ads recollected the lottery’s legacy as a permitted product in the marketplace: an icon with the words “30 YEARS” was bolded on many of the ads in their anniversary year to remind audiences that lottery gambling was and remains a well accepted practice with roots in local business, community and public life.

The message that gambling afforded a retreat or an escape from daily matters was a third theme found in about one in five of the radio ads. These commercials (N = 4) highlighted gambling as an alternative to work. In the ad Backbreaking the announcer exclaimed “Want to win a dream salary? …. play Atlantic PayDay every Thursday”, and went on to ask the question “What could you call two thousand dollars every two weeks for twenty years?” “A darn good job if you could get it” was the answer, and the ad then directed the listener to the names of several recent local winners. About 13% of television commercials also conveyed the message that gambling was a potential positive diversion from the vicissitudes of daily life (N = 12). These ads evinced another type of dream; a worry-free life after lotto: “The family is looked after”, said one character in one ad while another in a second ad insisted “The grind is gone”. Other turns of phrase such as “It just makes life that much easier”, or “Now life’s a little bit sweeter for the whole family” emphasized lottery play as a resolution to the stresses of everyday life. Average people could change their lives forever if they hit the jackpot and as the ads often intoned “Real people do win”. Other ads depicted how difficult it was for hard working people to get through the work day and encouraged viewers to anticipate alternate outcomes. One ad, Customer Service Representative, portrayed a young clerk in a call centre answering questions about satellite television. He explains the set up to a dim-witted customer on the telephone: “Find a TV button. Just give that a press. No, the TV button. The top of the remote. Yeah. And enter the code 635. 635. I’m telling you what the code is. 635.” In frustration with the customer who is unable to understand simple instructions, he screams the code 635 one more time while falling to his knees in a mantra-like gesture asking for peace from ignorant clients. The voiceover in the ad then reminds the viewer that work and frustration don’t have to go together. So why not try lottery gambling!

A final theme found in the ads was that gambling provided community benefits. About 17% of television commercials connected lottery gambling with the communal good (N = 15). For example, one ad evinced a “win-win” storyline text while the song “I feel good” played in the background. Winners were depicted dancing and singing, while lottery employees and players promoted the advantages of gambling to the community: new social services, better education facilities, enhanced economic development, support for sports, culture and the arts, and future civic notoriety for the region. Indeed, almost 40% of the print ads (N = 18) highlighted the message that personal “moments of fun” and individual “chances to dream” produced benefits for all. Scratch ‘N Win ads directly displayed this connection in their design: “Scratch ‘n” was located on the left side of the ad and highlighted in blue font on a white background, while the words “make it happen” were located on the right side and designed in white font on a blue background. The design and colour scheme drew the viewers’ eye to the heading text win “a top prize of $50,000” and to the subtext support “amateur sports in Atlantic Canada” or “the Commonwealth Games in Halifax in 2014”, thus appealing to new users through new uses for gambling.

Discussion

Advertising, Myth, and the Ethos of Winning

Taken together, lottery ads in Atlantic Canada evinced a complex assemblage of communication styles, tones, texts, sounds, images, appeals and messages that were circulated repeatedly to consumers. The advertisements, however, were more than blunt sales devices; they were models of and models for reality. Many of them hooked into pre-existing cultural practices and values (sport culture, the luck struck ideal, instant wealth and the joy of consumption, etc.) and used interactive communications to relay their messages to their audiences and encourage them to construct their self images through the imaginary of the ads (Gulas and Weinberger 2006; Sivulka 1998; Elliott 1999). Gambling commercials were attractive sign systems in which individual ads combined obvious and appealing signs (profit, success, luxury living, etc.) and easily understood intended meanings (buy a 649 ticket today) so that commercials naturalized the lotto products through irony (you can’t win if you don’t play rather than you won’t win if you do play!). To recall Barthes (1973, p. 128) semiological method for decoding advertising messages, at the level of the empty signifier a lottery product was linked to a series of signifiers which connoted consumer culture: sudden purchasing power, new found fame, long overdue leisure, and so on. These signifiers, in turn, were connected to a second order language of pleasure and excitement which was and remains omnipresent in the cultural products of contemporary society and which ordered advertisings’ general meaning in and to popular culture. At the level of the full signifier, consumers were invited to connect a particular lottery product to these wider domains of consumer culture. They may suspect that playing scratch cards or wagering on weekly draws does not or will not necessarily add up to enjoyment or prosperity (it may be tedious and costly). Yet at the same time the ads worked toward the consumer in a persuasive manner. Gaiety and gain were registered inside the ads and the messages intoned a wider, interdependent cultural appeal that overlapped with positive images of gambling found in films, news, television series and popular magazines; the sales pitch was not over-determined (designed as blatant manipulation) or under-determined (designed as meaningless or confusing). Instead, the connection between lotteries and their mythical attributes as hopeful dreams, reversals of fortunes and sound future investments were designed to seem momentarily plausible. The communication of the messages was subtle enough to stop consumers from rejecting it outright. Of course, they may suspect that their chances of winning 10 million dollars on Super 7 were slim to nothing but if they did not play, they cannot win. So, give them a TAG as well; you never know! was and is a repeated myth story of lottery gambling at once true and unreal. As Pateman (1983, p. 188) reminds us advertisements are retro-fitted communications where the sign systems and cultural codes of society have been reformatted by commercial interests so that they resonate with cultural values and meanings to sell commodities and gain product credibility.

The coded references that were deployed to sell lottery products as commodities included endless references to a “dream culture” dense with the symbols of affluence, desire, pleasure and leisure where the impossible was rendered possible because the allure of consequences eclipsed the world of likelihood and to an “ethos of winning” that conveyed a powerful imagery of plentitude and certitude in a world of likely loss and high risk (Binde 2009a, pp. 7–8; Griffiths 2005, pp. 17–18). The use of “real winners” in ads was an especially important way in which lottery advertisers capitalized on the cultural capital of their customers to “back-talk” their products through dialogic methods (“play it man, play it”, “just keep on scratchin”, “try your luck; it only costs two buck”) and to signify the wider credence and meaning of their products aside from price (“it was like the best moment ever”, “it was absolutely awesome”, “it’s a lot of fun”) (Elliott 1999; Thompson 1997). The use of real winners as story-tellers created poignant cultural frames of reference that played to the connections between biography and community. Some winners were portrayed in photo shoot formats and introduced as “just one of 350,000 Atlantic Canadians who win every week”; others were depicted more subtly as conspicuous consumers, buying, traveling and vacationing or as community benefactors hiring contractors, circulating capital, and stimulating economic growth. Indeed, the narrative form in the real winner ads was simple and straightforward. A past event of consumption (“I was going to buy batteries”) was relived by a winner in relation to a present concern (“I bought a scratch ticket and won a million dollars”) and projected toward an envisioned future which audiences were invited to identify with and appreciate collectively (“And it has been a great time ever since; keep on scratching”), or a named consumer (Kim Redden) from a familiar community (Newport, Nova Scotia) was shown re-experiencing a recent gambling win (“Scratched and won $50,000”) which was then parlayed to a happy outcome that was shared with viewers or listeners for their benefit and emulation (“Helped her build a new home”).

Aside from the obvious transformation of ordinary citizens into “community celebrities” to help engender trust in games, instill experiences of winning, and signify success, winners’ stories were also narratives that conveyed and circulated wider cultural meanings through a language that linked everyday subjective language and experience with prospective audiences. The power of these ads was in the interactive designs that allowed viewers and listeners to partake in cultural conversations and share in cultural myths. For example, winners were almost always connoted as either wise or altruistic to frame the engagement of the audiences with the messages/products. The wise winner was depicted as happy, sensible, in control, and forward looking. They planned for the future by buying new vehicles and property, investing in retirement schemes and taking stress-free holidays. They were happy and deserving and free to make over their lives in luxury and idleness. The altruistic winner was portrayed as happy, rich but generous. Gambling afforded self-fulfillment because it enabled familial acts of kindness and sharing, and allowed for communal forms of friendship which valorized consumption as a social form of pleasure and gambling as an unanticipated form of care for others. Winning did not entail excessive spending, envy, secrecy or marital and family discord as is often reported in the news when winners squandered jackpots or refused to share their wins with family or friends (Binde 2007b). Rather, consumer consumption stories were strategically designed to entice audiences to “take turns” with winning citizens and imagine themselves in their shoes, and to participate vicariously with the ads through positive anticipation: Would they be next? What would they do if they won? Would they too enjoy the good life of the mythical happy gambler? They were carefully positioned to tap into a dream world of hedonism where faith and hope were connected to a materialist love of money and a self-serving desire to increase capital and consume effortlessly and endlessly. Lottery winning was like a transcendental experience; it struck you forcefully and without warning, and converted you into a true believer. Good things happened to those who played lotteries and this message was designed to have resonance because the winner ads were imbricated with wider cultural messages coming from film, television and the internet giving them legitimacy and informing the sender of the message what was saleable and the receiver what to expect in the never ending world of continuous winning and dreaming.

Implications

These tangible and emotional qualities about wins, winning and winners in gambling ads were especially inviting to young people creating a positive orientation to lottery products that, in turn, reinforced them as part of youthful consumption practices (McMullan and Miller 2008a; Derevensky et al. 2007; Korn et al. 2005). Of course, this does not mean that lottery ads directly targeted adolescents as with beer and tobacco advertising. The targets were diverse and multiple but many of the actors and models depicted in the print and television ads were young adults, many ads aired at times and on programs directly attractive to youth, and many of the point of sale ads were located in places and at times where children and adolescents could see them (i.e. convenience stores, shopping malls, bus stops, drug stores) every time they went for a walk, met friends, shopped for clothes or bought drinks and candy. Indeed, the content and tone of many of the ads did try to connect to certain lifestyle clusters and social identity features that blended smoothly into a relatively youthful world enamored with wanting to have fun, get ahead fast, look for shortcuts to success, find quick fixes to problems, and overcome the fears and risks of the future. So, young people were a constant “by-catch” of inestimable value to lottery advertisers and providers. The former were encouraged to view gambling as “good times” where time out and fanciful fantasy were both normal and reasonable. These ads and their placements were paradoxical, enabling youth to see and hear them and recruiting them as future players on the one hand, while warning them that they could not play until they legally came of age on the other hand. Unlike big tobacco, which is being de-normalized in popular culture, state-based gambling is the latest example of how forbidden passions and pleasures have become transformed, legitimized and sold back to consumers as valuable and popular intangible products—a wishful winning way of life and an attractive pastime not unlike hang gliding, mountaineering, dirt biking or extreme sports. Consider the wins, winning and winners associated with lottery gambling, the ads proclaimed, but not it would seem against the potential risks, dangers, and harms, because they were either sadly absent or a source of ocular distress in much commercial lottery advertising.

Furthermore, this focus on winning and dreaming along with a high degree of product exposure and convenient availability are controversial and exploit some of the factors that research has shown contributes to at-risk gambling: the association between (a) wins, winning and winners and the propensity to invest in continuous play; (b) between overselling and overestimating winning returns and the propensity to chase losses; (c) between consumer myth making, faulty thinking and the real statistical probabilities of economic success and social mobility from gambling; and (d) between high awareness of availability of gambling products, high levels of exposure and consumption and the greater risks of developing potentially disordered conduct (Delfabbro 2004; Delfabbro et al. 2006; Messerlian et al. 2005; Turner and Horbay 2004; May et al. 2005). This does not mean that advertising caused problem gambling or youth gambling. But there is little doubt that enticing people with the prospects of huge jackpots, attractive consumer goods and easy wins, showcasing top prize winners, and providing dubious depictions that winning is imminent and life-changing is narrow and misleading, exploits themes that conflict with the state’s role as protector of the public good (i.e. luck over hard work, instant gratification over prudent investment, and spending over saving), and invites and empowers calls to limit or ban the advertising of gambling products (Binde 2009a; Monaghan et al. 2008; Poulin 2006; Griffiths 2005; Korn et al. 2005).

In all likelihood the gambling industry will face new restrictions regarding some forms of advertising and marketing as gambling continues to expand into a socially acceptable cultural practice. Of course, general advertising regulations and codes exist now and are reviewed from time to time, but they are often vague, inconsistent, voluntary and difficult to enforce in practice. So it perhaps goes without saying, but there should be a rethinking of some fundamental issues regarding: (a) the volume, frequency, costs and necessity of gambling advertising; (b) the adequacy, fairness and enforceability of the language of existing legislation governing such advertising; (c) the rules placed on the time, location, availability and accessibility of gambling advertisements; (d) the content and balance of impressions conveyed in gambling advertisements; (e) the ubiquity of lottery advertising and its impact on youth, people in low income communities and heavy players; and (f) the value of establishing independent, comprehensive gambling advertising acts to regulate different gambling products.

The starting point for rethinking these issues might best be precautionary and in line with preventative responsible gambling policies. Gambling providers should promote advertising that is not misleading, be restrictive with advertising that can be suspected of being misleading, and be mindful that the typical buyers of lottery tickets may hope for a “better means to express their ‘true self’” and not want to become a totally different person “living a new life in luxury and idleness” and face all the problems that such sudden transformation can cause them and their families (Binde 2009a, pp. 16–17). If gambling providers and regulators do not develop more comprehensive, balanced and socially responsible advertising policies than they may well become the architects of their own misfortune for failing to protect citizens from gambling-related harms caused by excessive, aggressive and misleading advertising.

References

Agres, S. J., Edell, J. A., & Dubitsky, T. M. (1990). Emotion in advertising: Theoretical and practical explorations. New York: Quorum Books.

Amey, B. (2001). Peoples participation in and attitudes to gambling, 1985–2000. Final results of the 2000 survey. Wellington, New Zealand: Department of Internal Affairs.

Atlantic Lottery Corporation. (2004–2005). Annual report. Retrieved June 21, 2007, from http://www.alc.ca/English/AboutALC/AnnualReport/Images/ALCAnnualReport2004-05.pdf.

Atlantic Lottery Corporation. (2005/2006). Annual report. Retrieved June 21, 2007, from http://www.alc.ca/English/AboutALC/AnnualReport/Images/ALCAnnualReport2005-06.pdf.

Atlantic Lottery Corporation. (2006/2007). Annual report. Retrieved February 5, 2008, from http://www.alc.ca/English/AboutALC/AnnualReport/.

Banks, M. (2001). Visual methods in social research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Barthes, R. (1973). Mythologies. St. Albans: Paladin.

Berger, A. A. (2000). Media and communication research methods: An introduction to qualitative and quantitative approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc.

Biener, L., & Siegel, M. (2000). Tobacco marketing and adolescent smoking: More support for a causal inference. American Journal of Public Health, 90(3), 407–411. doi:10.2105/AJPH.90.3.407.

Binde, P. (2007a). Selling dreams—causing nightmares? On gambling advertising and problem gambling. Journal of Gambling Issues, 20, 167–191.

Binde, P. (2007b). The good, the bad and the unhappy: The cultural meanings of newspaper reporting on jackpot winners. International Gambling Studies, 7(2), 213–232. doi:10.1080/14459790701387667.

Binde, P. (2009a). Truth, deception, and imagination in gambling advertising. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Binde, P. (2009b). Exploring the impact of gambling advertising: An interview study of problem gamblers. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Boughton, R., & Brewster, J. M. (2002). Voices of women who gamble in Ontario: A survey of women’s gambling, barriers to treatment and treatment service needs. Retrieved August 1, 2007, from http://www.gamblingresearch.org/download.sz.voicesofwomen_Boughton(1).pdf?docid=1524.

Chapman, S., & Egger, G. (1983). Myth in cigarette advertising and health promotion. In H. Davis & P. Walton (Eds.), Language, image, media (pp. 166–186). New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Chen, M. J., Grube, J. W., Bersanin, M., Waiters, E., & Keefe, D. B. (2005). Alcohol advertising: What makes it attractive to youth? Journal of Health Communication, 10(9), 553–565. doi:10.1080/10810730500228904.

Clotfelter, C. T., & Cook, P. J. (1989). Selling hope: State lotteries in America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Coffey, A., & Atkinson, P. (1996). Making sense of qualitative data: Complimentary research designs. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

D-Code Inc. (2006). Decoding risk gambling attitudes and behaviours amongst youth in Nova Scotia. Halifax: Nova Scotia Gaming Corporation.

DeJong, W., & Hoffman, K. D. (2000). A content analysis of television advertising for the Massachusetts Tobacco Control Program media campaign, 1993–1996. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 6(3), 27–39.