Abstract

Relapse rates among pathological gamblers are high with as many as 75% of gamblers returning to gambling shortly after a serious attempt to quit. The present study focused on providing a low cost, easy to access relapse prevention program to such individuals. Based on information collected in our ongoing study of the process of relapse, a series of relapse prevention booklets were developed and evaluated. Individuals who had recently quit gambling (N = 169) were recruited (through media announcements) and randomly assigned to a single mailing condition in which they received one booklet summarizing all of the relapse prevention information or a repeated mailing condition in which they received the summary booklet plus 7 additional booklets mailed to them at regular intervals over the course of a year period. Gambling involvement over the course of the 12-month follow-up period, confirmed by family or friends, was compared between the two groups. Results indicated that participants receiving the repeated mailings were more likely to meet their goal, but they did not differ from participants receiving the single mailing in frequency of gambling or extent of gambling losses. The results of this project suggest that providing extended relapse prevention bibliotherapy to problem gamblers does not improve outcome. However, providing the overview booklet may be a low cost, easy to access alternative for individuals who have quit gambling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Progress has been made in developing and evaluating intervention programs to help people quit gambling (Hodgins, Currie, el-Guebaly, & Peden, 2004; Hodgins & Petry, 2004; Sylvain, Ladouceur, & Boisvert, 1997). Overall, the findings suggest that treatment has a positive effect, at least in the short-term. However, it is also clear that relapse rates are high. Relapse is broadly defined as a resumption of problematic gambling after a period of abstinence. In recognition of high relapse rates, relapse prevention training, mostly adopted from the substance abuse treatment field, is increasingly included as a component in gambling treatment (e.g., McCown & Chamberlain, 2000; Sylvain et al., 1997).

Although treatment and self-help groups such as Gamblers Anonymous are currently available in most jurisdictions only a minority of problem and pathological gamblers choose to enter treatment. Self-change rates, i.e., quitting without formal intervention, appear to be high (Hodgins & el-Guebaly, 2000; Hodgins, Wynne, & Makarchuk, 1999). Self-changers decline available treatment and decide to initiate the change process “on their own” (Hodgins et al., 2000). Like treatment-seekers, these self-changers typically make a number of attempts at quitting gambling followed by relapse before achieving stable abstinence.

In a prospective study of the gambling relapse process that included both treatment-assisted and self-changers, 75% of participants had relapsed to gambling 3 months after they had quit. Generally, those participants who were involved in treatment and follow-up services (including Gamblers Anonymous) had better outcomes than those who were not involved. However, only 25% of the gamblers had any treatment and follow-up involvement (Hodgins, Peden, & Cassidy, 2005). The impetus for the current study was the need for effective relapse prevention interventions for the significant proportion of gamblers who are not attending support services after they have quit gambling. The project focused on reducing the rate of relapse of pathological gamblers through the provision of information materials through the mail. Such materials are low cost (compared with formal treatment), easy to access, and attractive to a wide range of pathological gamblers (Hodgins, 2004).

Mailing relapse prevention materials has been shown effective for people who have recently quit smoking (Brandon, Collins, Juliano, & Leavey, 2000). In that study ex-smokers were recruited through newspaper advertisements and were provided either a single booklet of information about relapse (the control condition) or repeated mailings (8 booklets on different topics over 12 months). At the 12-month follow-up, 12% of those receiving the repeated mailings were smoking again compared with 35% in the control condition. Two elements of the repeated mailings intervention were assumed to be important: the extended contact and the coping skills training provided in the booklets (Brandon et al., 2000). Extended contact may act by maintaining high levels of participant motivation to continue abstinence.

For this study, relapse prevention booklets were developed based on information collected from our previous research on the process of relapse (Hodgins & el-Guebaly, 2004) and recovery (Hodgins et al., 2000). Pathological gamblers who had recently quit gambling and who were not involved in ongoing treatment or support were recruited through the media. They were randomly assigned to receive one summary relapse prevention booklet or a series of repeated mailings over an 11-month period. It was hypothesized that gamblers receiving the repeated mailings would gamble less in the follow-up year.

Method

Development of Relapse Prevention Booklets

The first phase of the project involved developing and piloting the series of relapse prevention booklets. The data collected in our study of relapse was analyzed and provided a wealth of data on precipitants of relapse and effective coping strategies (Hodgins et al., 2004a, b). This information was integrated with the theoretical and treatment literature available in the areas of gambling and substance abuse. We developed eight booklets with topics such as: dealing with urges to gamble, negative emotions as a cause of relapse, “getting back on the wagon” after a relapse, lifestyle balance, financial issues, stages of change, and dealing with comorbid emotional and addiction problems. In addition, an overview booklet was developed that very briefly summarized all the topics. The booklets were revised according to feedback from clinicians and pathological gamblers. The reading level was limited to Grade 6 and the booklets were brief and easy to read (10 pages each).

Clinical Trial

Procedure

Media announcements (press releases, paid advertisements, flyers) were used to recruit individuals who had recently quit gambling. The announcements offered free relapse prevention information. Both urban and rural settings were targeted across Alberta and Newfoundland, Canada. Interested individuals called a toll-free number and were provided with information about the study by the research assistant. Inclusion criteria were as follows: over age 17, met DSM-IV lifetime criteria for pathological gambling, (as measured by the NODS, Gerstein et al., 1999), a goal of quitting gambling and, to ensure serious intention to quit, no gambling for a minimum of two weeks (despite access to money and gambling), not involved in treatment or Gamblers Anonymous at present, willingness to read short booklets written in English (to ensure reading ability), willingness to have telephone contacts recorded, willingness to provide follow-up data on gambling, willingness to provide the name of a collateral to help locate them for follow-up interviews, and the name of the same or a different collateral for data validation.

Recruitment

Approximately 227 inquiries were made to the study over a 12-month recruitment period. Sixty-one individuals were not eligible for the study, most often due to current treatment involvement (24%) or insufficient length of abstinence (18%). Calls were also received from individuals who were subsequently unreachable (20%). Other frequent reasons for ineligibility were: caller did not meet NODS criteria (15%), disinterest (13%), caller was not a gambler (e.g., family member)(9%), caller could not speak English (2%).

Participants’ demographic and gambling history characteristics are presented in Table 1. Depression rates were high according to the CES-D (M = 21.5 SD = 16). These scores were much higher than the general population of white respondents (M = 7.94 to 9.25) and comparable to those of psychiatric patients (M = 24.4; Radloff, 1977). Over half (54%) of participants reported past treatment for emotional/mental health difficulties. As seen in Table 1, 42% of the participants were female and the average age was 32 (SD = 11.2, range 21–65). Most participants reported problems with video lottery terminals (electronic gaming machines, 81%), followed by slot machines (38%), and casinos (20%).

Random Assignment

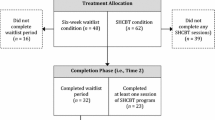

Participants were informed that two different information packages were being compared but they were not provided with a detailed description of the differences. They were stratified on gender, age and problem severity and randomly assigned to one of the two groups: Group 1: Repeated Mailings: Booklets were mailed immediately and at 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11 months after the initial assessment beginning with the overview booklet. Group 2 Single Mailing: The overview booklet was mailed immediately.

Of the 169 participants, 84 and 85 were randomly assigned to the repeated and single mailing conditions, respectively. The success of random assignment of participants to the two conditions was determined by comparing the groups across the initial assessment variables using t-tests and Pearson Chi square analyses. There were no significant differences between the groups among any of the variables.

Initial Assessment

The initial telephone assessment was conducted by a research assistant and was designed to be as brief as possible in order to minimize the research contact with participants. The components of the interview were: a Gambling History including a timeline followback interview measuring types of gambling, frequency, and money spent for the past 2 months of gambling (Hodgins & Makarchuk, 2003); two measures of Gambling Severity, the NODS, which measures DSM-IV symptoms (Gerstein et al., 1999) and the SOGS (Lesieur & Blume, 1987); a measure of self-efficacy (Gambling Abstinence Self-efficacy Scale (GASS; Hodgins, Peden, & Makarchuk, 2004); a measure of motivation (0 to 10 point scale; Hodgins, Currie, & el-Guebaly, 2001); and a measure of depression (Centre of Epidemiologic Studies—Depressed Mood Scale—CES-D; Radloff, 1977).

Outcome Variables

Follow-up assessments were conducted by telephone on 3 occasions after the initial assessment (6, 24, and 52 weeks) by a research assistant who was unaware of the participant’s assigned group. At each of the follow-up assessments, a time-line followback interview captured the number of days of gambling during the follow-up period and the amount of money spent on each occasion. In addition, participants were asked whether they had met their goal during the follow-up period (not at all, partially, mostly, completely), had any treatment or GA involvement, whether treatment was available locally and were asked to indicate their present goal (quit all types of gambling, quit only problematic forms, control). In addition the self-efficacy and motivation measures from the initial interview were re-administered. At the 12-month follow-up, the measures of gambling severity were re-administered.

Process Variables

At the 12-month follow-up assessment participants were asked whether they read the booklet (or booklets) during the follow-up interval (not at all, some sections, completely) and, if so, whether they had followed the procedures (not at all, to some extent, completely) and used the strategies (not at all, occasionally, regularly). These questions were modified from Sanchez-Craig, Davila, and Cooper (1996). In addition, if participants were in the repeated mailing group, they were asked “Did you: Read all of the booklets completely, Read some sections of each booklet, Read a few booklets completely and a few booklets only some sections, skim through the booklets, or not read them at all.” All participants were also asked an open-ended question about what they had done that was helpful in staying away from gambling. The research assistants probed responses fully.

Collateral Reports

At the 6-month follow-up, participants were asked to provide the name of a collateral who was aware of their recent gambling involvement. One collateral per participant was contacted by telephone as soon as possible.

Statistical Analyses

Two major dependent variables for testing the primary hypothesis were used: mean number of days per month gambled and mean dollars lost per month gambling. These variables were calculated for the 2 months before quitting and for the 6- and 12-month follow-up period. The 6-week follow-up data are not included in this report because group differences were not expected early in the follow-up because participants received the same materials in the first mailing. The included data were inspected for normality and were subjected to appropriate transformation (natural log). The general analytic approach for continuous variables employed repeated measure ANOVA comparing the two groups across the three time periods (initial, 6 and 12 months). Analyses were conducted with both the completers (those followed) and using an intention-to-treat model with the initial observation carried forward. The results were very similar using these two approaches so only the completers analyses are reported. The general analytic approach used for categorical variables was Pearson χ2-analysis. The responses to the open-ended question concerning useful actions were sorted into content categories by two independent raters (Taylor & Bogdan, 1984).

Follow-up Rates

The follow-up rate at 6 months was 146 (86%) and 142 (84%) at 12 months. Follow-up rates did not vary according to treatment group. No differences in other demographic or gambling variables were found between those followed and lost.

Results

Overall Relapse Rates

At the 6-month follow-up, 78% of participants had relapsed at least once. At 12 months, 77 % of participants had gambled since the 6-month interview. Table 2 displays the percent of participants categorized by days gambled at each time period and includes data from our previous study on relapse as a comparison (Hodgins et al., 2004a, b). In the 2 months prior to the study, 53% of participants reported gambling 8 or more times per month. In months 10 to 12, only 9% gambled at this rate.

Days and Dollars Gambled per Month

The number of days and dollars per month spent gambling was highly positively skewed for each follow-up period. The raw data were logged to improve the shape of the distribution. Two participants at each follow-up reported extremely large dollar losses which were recoded to the next higher value prior to the transformation. Although analyses were conducted on transformed data, for ease of interpretation Table 3 displays the means and standard deviations of the raw data at each time period. For days per month a repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant time effect, F (2, 254) = 187.6, p < .0001, but no group x time interaction, F(2,254) = 1.17. Post hoc analyses showed both the groups decreased days gambled from initial to 6-month follow-ups (p < .0001) with no change between 6 and 12 months. Similarly, an ANOVA revealed a significant time effect for dollars per month, F (2,256) = 103.9, p < .0001 but no group x time interaction, F(2,256) = .79. Post hoc analyses showed the groups decreased dollars spent from initial to 6-month follow-ups (p < .0001) with no change between 6 and 12 months.

Gambling Abstinence Self-efficacy Scale

The GASS is a measure of how confident an individual is that he or she could abstain from gambling in various situations. Higher scores indicate a greater level of confidence. An ANOVA revealed a significant time effect, F(2, 254) = 9.4, p < .0001, but no group by time interaction, F(2, 254) = 1.0. Post hoc analyses showed the groups increased GASS scores from initial to 6 months (p < .0001). There was no significant difference between 6 and 12 months (p = .09). There was a marginally significant group difference in GASS scores at the initial interview (p < .10). Therefore, a 2 × 2 ANCOVA was conducted with one between group factor (2 groups) and one repeated measure factor (6- and 12-month follow-up). The initial GASS value was included as a covariate. A significant group effect was not found, F(1, 126) = .004.

Centre of Epidemiologic Studies—Depressed Mood Scale (CES-D)

An ANOVA was conducted with one between group factor (2 groups) and one repeated measure factor (initial and 12-month follow-up). A significant time effect, F(1, 136) = 15.6, p < .0001 (a drop in depression from initial to 12 months) was found while the group x time interaction was not significant, F(1, 136) = .32.

South Oaks Gambling Screen

An ANOVA was conducted with one between group factor (2 groups) and one repeated measure factor (initial and 12-month follow-up). A significant time effect F(1, 136) = 8.13, p > .0001, but no group × time interaction, F(1, 136) = .01. There was a marginally significant group difference in SOGS scores at the initial interview (p = .08). Therefore, a univariate ANCOVA was also completed comparing the two groups at the 12-month follow up with the initial score covaried. A group difference was not found, F(1, 135) = .2.

At the initial assessment, 96.3% of the sample exceeded the clinical cutoff of the SOGS (5 or greater), indicating probable pathological gambler. At the 12-month follow-up, 70% of those followed (n = 140) continued to exceed the cutoff.

NODS

An ANOVA was conducted with one between group factor (2 groups) and one repeated measure factor (initial and 12-month follow-up). A significant time effect, F(1, 138) = 170, p < .0001, was found but no group x time interaction, F(1, 138) = .02.

At the initial assessment, 95% of the sample exceeded the clinical cutoff of the past year NODS (5 or greater), which indicates DSM-IV pathological gambling. At the 12-month follow-up, 54% of those followed (n = 140) continued to exceed the cutoffs.

Goal Attainment

Table 4 displays the percentage of participants who met their goal at 6 and 12 months. At 12 months, participants in the repeated mailing group were more likely to meet their goal than those in the single mailing group, χ2(3, N = 142) = 7.9, p < .03, but not at 6 months, χ2(3, N = 145) = 0.5. Table 5 examines participants’ description of their current goal at each time period. At 12 months, participants in the treatment group were more likely to want to quit all types of gambling, χ2(2, N = 142) = 8.2, p < .02, but not at 6 months, χ2(2, N = 145) = 1.0.

Treatment-seeking

At 6 months, 16% of the repeated mailing group received treatment compared to 14% of the single mailing group (n = 145). Treatment was available locally to 81% of participants (10% did not have access to treatment and 8% did not know if treatment was available). By 12 months, 24% of the repeated mailing group had received treatment compared to 20% of the single mailing group (n = 140).

Collateral Verification of Gamblers’ Self-reports

After the 6-month interview, an attempt was made to contact by telephone one collateral per participant in order to assess the validity of the gamblers’ self-reports. The collateral interviewer was unaware of the participant’s report. Overall, ninety-five collaterals were interviewed. However, twenty-one of these collaterals were contacted after the 12-month interview either because they were unreachable at 6 months or because the gambler could not provide the name of a collateral until the 12-month interview. Collaterals were contacted on average 16 days after the 6- or 12-month interview with the participant (SD = 23.5, Range 0–125). Collaterals reported knowing the gambler for 17.6 years (SD = 13.5, Range, 1–53). The majority of the collaterals were spouses (48%) or other intimate relationships (6%) followed by other family members (22%), friends (18%), roommates (1%), and other (4%). The collateral was asked about the participant’s involvement with gambling over the past 2 months and to rate their confidence in the accuracy of these reports (not at all, somewhat, fairly and extremely). There were only four collaterals who were not at all confident for total days and dollars and three collaterals who were not at all confident regarding whether the gambler had sought treatment. These collaterals were excluded from the present analysis (results including these individuals did not differ significantly). Intraclass correlation coefficients were 0.60 for days of gambling and 0.63 for total dollars lost from gambling over the past 2 months. Both these coefficients fall in the good range of agreement according to interpretation guidelines (Cicchetti, 1994).

Use of the Materials

There were no group differences in self-reports of reading the materials. At the 6-month follow-up, 63% of participants reported having read the materials completely with an additional 29% reading “some sections”. Only 8% reported not reading them at all. Ninety-six percent (138 out of 144) had retained the booklet or booklets at 6 months. By 12 months, 56% of participants reported having read the materials completely with an additional 36% reading “some sections”. Again, only 8% reported not reading it at all.

Use of strategies did not differ between groups at 6 months but by 12 months, participants receiving the repeated mailings were more likely to report use the strategies regularly than the single booklet group. (24% vs. 13%) and less likely to report never using them (21% vs. 30%), χ2(2, N = 136) = 6.7, p < .05.

Actions Taken to Avoid Relapse

At the 12-month interview, participants were asked what actions were helpful in avoiding a relapse. Table 6 reveals the various categories that were uncovered in the content analysis of these responses. Keeping busy or getting involved in new activities was the largest category followed by limiting access to money. Accessing treatment and stimulus control (staying away from gambling locales or gambling associations) were also frequently endorsed.

Discussion

Gamblers were successfully recruited through media advertisements and the majority of participants were followed at 6 and 12 months. The project appealed to gamblers reporting a variety of types of gambling although the largest group experienced VLT problems. Almost half of the sample reported having problems with more than one type of gambling. Participants recruited were individuals with substantial gambling problems in the last year as indicated by the SOGS (M = 11) and the NODS (M = 8). Over half had a treatment history related to their gambling and almost the entire sample had made previous quit attempts. Rates of alcohol, other drug disorders, and smoking were high. Gamblers also appeared to be experiencing a significant degree of depression (as indicated by high CES-D global scores) and over half reported past treatment for emotional health difficulties. These high rates of co-morbidity are consistent with other studies (Crockford & el-Guebaly, 1998; Petry, 2005).

The 6 and 12-month follow-up data, confirmed by collateral reports, indicate that the single and repeated mailing groups showed significant improvement in overall gambling as indicated by SOGS and NODS scores and fewer gambling days and dollars lost. Self-efficacy also increased significantly for both groups and overall, the sample exhibited fewer depressive symptoms.

Although general improvement was evident, it is also clear that a majority of participants continued to experience problems as indicated by the NODS (54%) and SOGS (70%). In terms of their initial goal of quitting gambling, 44% of the overall sample was abstinent for the past 3 months at the 12-month follow-up. This rate is similar to the rate found in our naturalistic study of the process of relapse (Hodgins et al., 2004a, b) where no intervention was provided.

Despite general improvement, there was no evidence that receiving periodic booklets over the follow-up period led to improved outcomes on any of these variables. Overall, the sample reported being extremely motivated at the start of the study which may account, in part, for the improvements reported. These participants appeared “ready to change” and were clearly motivated enough to initiate some self-change as a result of being involved in a research study. The extended contact (i.e., follow-up interviews) may have also contributed to the maintenance of their motivation. Indeed, the general patterns among the various outcome measures was improvement to 6 months followed by maintenance of change over the final 6 months. Finally, the overview book may have been comprehensive enough for these individuals to utilize and refer back to over the year. Most participants retained this booklet. The major limitation of this study was the lack of a no-contact control group. In the absence of such a control, it is unclear whether the booklet or contact had an impact on the natural history of gambling among these individuals.

It is notable that participants in the repeated mailings group were significantly more likely to meet their goal at least partially. Moreover, this group tended to retain a more strict abstinence goal over time. All participants initially indicated that their goal was to quit gambling (or quit their problem type) as opposed to cutting back or controlling their gambling. However, by the 12-month follow up, participants in the single mailing group were significantly more likely to report that their goal had changed to controlling their gambling. Perhaps the more comprehensive booklets provided the treatment participants with a more realistic view regarding the need to quit gambling completely.

Almost all of the participants who had received the booklets reported that they had read at least some sections (92%) and the majority reported using the strategies and procedures. Gamblers reported engaging in a variety of actions in reaching their goal. The predominant change strategies were keeping busy (i.e., becoming involved in new activities) and limiting access to money. Accessing treatment and stimulus control (staying away from gambling locales or gambling associations) were also common responses. With the exception of limiting access to money, these strategies are consistent with responses from a group of resolved gamblers interviewed in previous research study (Hodgins et al., 2000). These strategies were highlighted in the overview relapse booklet provided to all participants, although it is also possible that participants, having already quit gambling, were engaging in them naturally.

The results of this project suggest that providing extended relapse prevention bibliotherapy to problem gamblers does not improve outcome. However, providing the overview booklet may be a low cost, easy to access, alternative for individuals who have quit gambling.

References

Brandon, T. H., Collins, B. N., Juliano, L. M., & Leavey, S. B. (2000). Preventing relapse among former smokers: A comparison of minimal interventions through telephone and mail. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 103–113.

Cicchetti, D. V. (1994). Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment, 6, 284–290.

Crockford, D. N., & el-Guebaly, N. (1998). Psychiatric comorbidity in pathological gambling: A critical review. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 43, 43–50.

Gerstein, D., Murphy, S., Toce, M., Hoffman, J., Palmer, A., Johnson, R. et al. (1999). Gambling impact and behaviour study: Report of the national gambling impact study commission.

Hodgins D. C. (2004). Workbooks for individuals with gambling problems: Promoting the Natural recovery process through brief intervention. In L’Abate L. (Ed.), Using workbooks in mental health: Resources in prevention, psychotherapy, and rehabilitation for clinicians and researchers (pp. 159–172). Binghamton, NY: The Haworth Reference Press.

Hodgins, D. C., Currie, S. R., el-Guebaly, N., & Peden, N. (2004). Brief motivational treatment for problem gambling: 24 month follow-up. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 18, 293–296.

Hodgins, D. C., Currie, S. R., & el-Guebaly, N. (2001). Motivational enhancement and self-help treatments for problem gambling. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69, 50–57.

Hodgins, D. C., & el-Guebaly, N. (2000). Natural and treatment-assisted recovery from gambling problems: A comparison of resolved and active gamblers. Addiction, 95, 777–789.

Hodgins, D. C., & el-Guebaly, N. (2004). Retrospective and prospective reports of precipitants to relapse in pathological gambling. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 72–80.

Hodgins, D. C., & Makarchuk, K. (2003). Trusting problem gamblers: Reliability and validity of self-reported gambling behavior. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 17, 244–248.

Hodgins, D. C., Peden, N., & Cassidy, E. (2005). The association between comorbidity and outcome in pathological gambling: A prospective follow-up of recent quitters. Journal of Gambling Studies, 21, 255–271.

Hodgins, D. C., Peden, N., & Makarchuk, K. (2004). Self-efficacy in Pathological Gambling Treatment Outcome: Development of a Gambling Abstinence Self-efficacy Scale (GASS). International Gambling Studies, 4, 99–108.

Hodgins, D. C., & Petry N. M. (2004). Cognitive and behavioral treatments. In J. E. Grant, & M. N. Potenza (Eds.), Pathological gambling. A clinical guide to treatment (pp. 169–188). New York: American Psychiatric Association Press.

Hodgins, D. C., Wynne, H., & Makarchuk, K. (1999). Pathways to recovery from gambling problems: Follow-up from a general population survey. Journal of Gambling Studies, 15, 93–104.

Lesieur, H. R., & Blume, S. B. (1987). The South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS): A new instrument for the identification of pathological gamblers. American Journal of Psychiatry, 144, 1184–1188.

McCown, W. G., & Chamberlain, L. L. (2000). Best possible odds. contemporary treatment strategies for gambling disorders. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Petry, N. M. (2005). Pathological gambling. Etiology, comorbidity, and treatment. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association.

Radloff, L. H. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401.

Sanchez-Craig, M., Davila, R., & Cooper, G. (1996). A self-help approach for high risk drinking: Effect of an initial assessment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64, 694–700.

Sylvain, C., Ladouceur, R., & Boisvert, J. (1997). Cognitive and behavioral treatment of pathological gambling: a controlled study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65, 727–732.

Taylor, S., & Bogdan, R. (1984). Introduction to qualitative research methods: The search for meanings (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley.

Acknowledgements

This project was made possible with funding support from the Alberta Gaming Research Institute. We would like to thank Nicole Peden, Karyn Makarchuk, and Susan Green for working with us to write the workbooks. Nicole Peden and Erin Cassidy were responsible for data collection. Finally, we would like to thank the participants who gave freely of their time despite the struggles they were facing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hodgins, D.C., Currie, S.R., el-Guebaly, N. et al. Does Providing Extended Relapse Prevention Bibliotherapy to Problem Gamblers Improve Outcome?. J Gambl Stud 23, 41–54 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-006-9045-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-006-9045-1