Abstract

While the traditional model of genetic evaluation for breast cancer risk recommended face-to-face disclosure of genetic testing results, BRCA1/2 testing results are increasingly provided by telephone. The few existing studies on telephone genetic counseling provide conflicting results about its desirability and efficacy. The current study aimed to (1) Estimate the prevalence among genetic counselors of providing BRCA1/2 genetic test results by phone (2) Assess patient satisfaction with results delivered by telephone versus in-person. A survey was sent to members of the Familial Cancer Risk Counseling Special Interest Group via the NSGC listserve and was completed by 107 individuals. Additionally, 137 patients who had received BRCA genetic testing results either by phone or in-person at UNC Chapel Hill Cancer Genetics Clinic were surveyed regarding satisfaction with the mode of their BRCA1/2 results delivery. The genetic counseling survey revealed that the majority of responding counselors (92.5%) had delivered BRCA1/2 genetic test results by telephone. Patients having received results either in person or by phone reported no difference in satisfaction. Most patients chose to receive results by phone and those given a choice of delivery mode reported significantly higher satisfaction than those who did not have a choice. Those who waited less time to receive results once they knew they were ready also reported higher satisfaction. This study found supportive results for the routine provision of BRCA1/2 genetic test results by telephone. Results suggest that test results should be delivered as swiftly as possible once available and that offering patients a choice of how to receive results is desirable. These are especially important issues as genetic testing becomes more commonplace in medicine.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

According to the American Cancer Society, breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer in women and the second leading cause of cancer deaths in women after lung cancer (American Cancer Society 2008). Approximately 180,000 new cases of breast cancer are diagnosed each year, with over 40,000 deaths from this disease (National Cancer Institute 2008).

Mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes result in a substantially increased risk for developing breast and ovarian cancer. The normal gene products act as tumor suppressors and confer risk through mutation of the wild type allele and subsequent loss of function of tumor suppressor activity (Petrucelli et al. 2005). Estimates for the penetrance of mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 have varied, but appear to confer a lifetime risk for women of up to 87% for developing breast cancer and up to 68% for the development of ovarian cancer (National Cancer Institute 2008). The prevalence of BRCA1/2 mutations in the general U.S. population is 1–2 per 1,000, and genetic testing for these mutations has been available to the general public since 1996 (Petrucelli et al. 2005).

Regarding BRCA1/2 mutation testing, the current guidelines recommend testing be performed after provision of pre-test education by a trained genetics professional and formal client consent. The process of informed decision-making may or may not be completed in a single visit and final testing results should be provided in person by the same genetics professional who performed the pre-test counseling (American College of Medical Genetics Foundation 1999). Due to the nature of results disclosure and the fact that post-test counseling is a multi-step process, the NSGC recommends that this process optimally be done face-to-face. Elements included in this session are not only results disclosure, but discussion of impact of test results, medical management decisions, informing other relatives, encouragement of future contact with the clinic, and provision of additional resources and support services, all of which may be difficult to adequately address over the telephone or in a letter (Trepanier et al. 2004). Billing and legal issues may also pose barriers for genetic counseling by telephone (Ormond et al. 2000). For these reasons, current guidelines suggest telephone counseling for test result disclosure only in special circumstances, such as for clients who do not live locally or who are terminally ill. Consequently, most cancer programs in the past have required at least two clinic visits, a pretest visit and results disclosure visit, with some programs requiring additional visits (Schneider 2002).

The recommendations of The American College of Medical Genetics (1999) and NSGC have been influenced greatly by the protocol established for pre-symptomatic Huntington Disease (HD) testing (Baker et al. 1998; International Huntington Association and World Federation of Neurology Research Group on Huntington’s Chorea 1994) which recommends three in-person visits with a genetics professional as well as psychological and neurological evaluations. Advocates for modeling familial breast cancer genetic testing protocols on the HD model have noted that genetic testing for both conditions is predictive in nature. However, crucial differences between the two diseases include the fact that preventive measures are available in the realm of breast cancer risk and that the population prevalence of mutations in BRCA1/2 far exceed that of mutations in the HD gene. Given the increasing frequency of BRCA1/2 genetic testing in routine clinical care, its established role as an important aspect of oncologic care for many women and little (if any) evidence of harm resulting from such testing, it is reasonable to re-examine the need for in-person results disclosure.

Ideally, telephone counseling can provide a clinical service that is efficacious, convenient, cost-effective, accessible and educational, while at the same time maximizing the efficiency of clinics so that they can serve a maximal number of patients. The service is becoming increasingly more prevalent for prenatal teratogen counseling and is a standard method for delivering prenatal genetic test results (Ormond et al. 2000). Genetic counselors surveyed in a previous study (Young 1993) indicated that the majority utilized the telephone to discuss and deliver information to patients, including delivery of normal test results, and were motivated to do so primarily by the patient’s convenience. However, the majority of counselors in this study also reported never delivering inconclusive or abnormal test results over the telephone. Consequently, there is interest in determining the feasibility of providing high-quality counseling in the context of BRCA1/2 testing results by telephone.

A number of studies have investigated various facets of telephone delivery of breast cancer risk information and BRCA1/2 genetic testing results. These studies have previously shown that both in-person and telephone counseling and results delivery have been generally well-received (Helmes et al. 2006; Klemp et al. 2005). One observed difference, however, was that patients who received breast cancer risk counseling by telephone found it more difficult to talk about their concerns with one woman reporting that her telephone counseling session was “easier to become distracted than face-to-face”. Another difference found was that more women who received telephone counseling would rather have received in-person counseling (Helmes et al. 2006). In regard to results delivery, no difference in satisfaction has been shown between those who receive BRCA1/2 genetic testing results over the phone versus those who receive results in person (Chen et al. 2002; Jenkins et al. 2007). When given a choice as to how to receive results, most individuals choose to receive their BRCA1/2 genetic testing results by telephone (Klemp et al. 2005). No previous studies have reported the prevalence of telephone usage to provide cancer genetic test results, nor the specific circumstances under which these test results are being provided by telephone. Thus, there is need for current and further investigation of telephone BRCA counseling and results delivery.

As discussed by Peshkin et al. (2008), genetic counseling and testing services are increasing, particularly as additional genes are characterized and additional genetic tests become clinically available. Exploring alternative methods to traditional face-to face genetic counseling is imperative to devise service delivery mechanisms which meet this increase in demand. One of these methods, utilizing the telephone for counseling and/or delivery of results, has been and is currently utilized, but there exists a lack of data about its use and effectiveness from patient and provider perspectives. In this study we investigated the prevalence of provision of BRCA1/2 results by telephone among genetic counselors in the U.S as well as patient satisfaction with the mode of results delivery at our institution. The results have broad implications for medical management as the impact of genetics continues to expand in medicine.

Methods

This study consisted of two parts, Current Genetic Counseling Practices and Patient Satisfaction. The study was conducted under the approval of the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill IRB and the University of North Carolina Greensboro IRB.

Part I: Current Genetic Counseling Practices

The first part of the study assessed the prevalence and circumstances accompanying delivery of BRCA1/2 genetic test results by telephone in current cancer genetic counseling practices throughout the US. Members of the National Society of Genetic Counselors (NSGC) Familial Cancer Risk Counseling Special Interest Group (SIG) (n = 476) were sent an invitation through their listserv to an electronic survey adapted to Survey Monkey. This group was selected to survey because it represents a large accessible population of practicing cancer genetic counselors.

The survey (see Appendix A) was developed by the researchers as an original measure and piloted to several practicing genetic counselors. The measure included questions to ascertain how many counselors currently deliver BRCA1/2 genetic test results by telephone, what percentage of their patient population is receiving results in this manner, and the clinical and social circumstances of the patients for whom results are provided by telephone. A list of circumstances under which a counselor may or may not deliver BRCA1/2 genetic test results over the phone was provided for negative and positive results. The counselor was then asked to answer whether they usually, sometimes, rarely, or never provide results over the telephone for each circumstance (Table 1).

Genetic counselors who responded that they do not deliver any BRCA1/2 test results to patients were excluded from the study. One hundred seven qualifying individuals responded to the invitation by completing the survey yielding an estimated response rate of 22.5%. The survey was anonymous and submission of the survey was electronic.

The survey was available for 4 weeks, and an electronic reminder letter was issued to the NSGC Cancer listserv approximately 2 weeks after the first letter was issued to increase participant response. All quantitative data were analyzed and reported using frequencies calculated by the Survey Monkey program.

Part II: Patient Satisfaction

The second part of the study was designed to assess patient satisfaction with the mode of BRCA1/2 genetic test results delivery. Surveys were mailed to 379 patients who had undergone BRCA1/2 genetic testing through the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill (UNC-CH) Cancer Genetics Clinic. A subset of patients, those who were African–American, were not invited into this study because they had previously been invited to participate in a concurrent study. The remaining patients were therefore randomized alphabetically by last name to participate in this study. The study sample included patients who did not have a choice as to how to receive their results (mostly patients seen prior to 2005 when the practice of the UNC Chapel Hill Cancer Genetics Clinic was to deliver all results in person) and patients who were provided a choice of telephone or in-person results disclosure (practice that began in 2005).

The patient survey (see Appendix B) was created as an original measure after reviewing several genetic counseling satisfaction surveys posted on the NSGC website (Lea 1996; Middleton and Rodriguez 1997; Rhee-Morris 2006). The measure was used to assess an overall satisfaction score of the results session experience for each individual. Participants were provided with a list of statements pertaining to their results session and asked to strongly disagree, disagree, agree, or strongly agree with each statement using a summative Likert scale to calculate a total satisfaction score. These scores were then divided by the amount of the answered items to produce an average satisfaction score for each individual. These averaged scores where then used to compare satisfaction between those who received their results in-person versus those who received their results over the telephone. Satisfaction scores were also compared between those patients who reported that they had a choice as to how to receive their results versus those who reported not having had a choice. As the goal of our study was to evaluate satisfaction in the context of mode of results delivery and choice of mode of results delivery, for those individuals who may not have recalled how they received their genetic test results or whether they had a choice in their mode of results delivery, the option of “unsure” was provided for these questions to allow these responses to be eliminated in data comparison and analysis.

To test the accuracy of patients’ recall of their results, surveys were color-coded depending on the type of result the patient received: positive (55 individuals), negative (307 individuals), or variant of unknown significance (17 individuals). Participants were asked to report their result and responses were checked for accuracy, without identifying individuals, by matching their response to the color-coded survey they were sent.

Results were analyzed using SPSS. The satisfaction scores were checked for normality using One-Sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test and found to lack normality. Therefore, all comparisons of satisfaction scores between groups were made using nonparametric tests such as Kruskal-Wallis Test, Man-Whitney Test, and Chi-Square analyses. Cross-Tabulations and frequencies were used to describe variables of the study population.

Results

Part I: Current Genetic Counseling Practices

Of the estimated 476 genetic counselors belonging to the Cancer Special Interest Group, 107 individuals responded to the invitation by completing the survey for a response rate of approximately 22.5%. Eight of the respondents (7.5%) reported that they had never delivered BRCA1/2 genetic test results to patients by telephone and were not asked to answer any further questions.

Frequency of Phone Results Disclosure

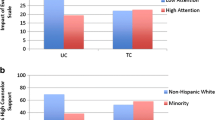

Of the 99 individuals who had delivered results by telephone in the past 12 months, the majority (63.9%) reported that 25% or less of their patient population received their BRCA1/2 genetic testing results in this manner (Fig. 1).

Participating genetic counselors were asked to estimate how often they provided telephoned results in the past 12 months according to the type of result (Fig. 2). Counselors provided phone results “sometimes or usually” for positive, negative, or variant results 33.0%, 55.7% and 33.7% of the time, respectively. While there was no difference between the frequency of phone results among patients with positive or variant results (p = 0.9187), both positive and variant results were given significantly less often over the telephone than were negative results (Positive vs. Negative: OR = 0.39, CI 95% 0.22–0.70, p = 0.0015; Variant vs. Negative: OR = 0.40, CI 95% 0.23–0.73, p = 0.0022.)

Circumstances Surrounding Phone Disclosure

Genetic counselors were provided with a list of possible circumstances under which one might or might not deliver BRCA1/2 genetic test results over the telephone and were asked for each circumstance whether they would “usually, sometimes, rarely or never” provide results by phone. In the positive result scenario, the most common preference was to never deliver this type of result by telephone, regardless of the circumstance provided (Table 1). From a list of possible circumstances under which a genetic counselor might give negative results, the most commonly chosen answer was also to never deliver this type of result over the telephone (Table 1). However, in specific circumstances, such as: “When patients are unable to return to clinic due to illness or travel issues” and “When I feel confident that I will have an opportunity to follow up with the patient face to face” the highest percentage of individuals (34.8% and 29.0% respectively) answered that they usually would deliver these negative test results over the telephone.

Genetic counselors were also given the opportunity to provide open-ended responses regarding circumstances under which they might deliver positive and/or negative results over the telephone. Respondents’ reasons for providing phone results included: exceptional types of situations, routine practice by their institution, delivery of preliminary results while BART© (an additional testing method offered by Myriad Genetics Laboratory to high risk patients who receive negative results) results are pending, and delivery of BART results.

Part II: Patient Satisfaction

The primary goal of Part II in this study was to determine patient satisfaction at our institution with respect to how their BRCA1/2 results were delivered. The response rate for patient surveys was 36.1% (137/379). Demographics of responders are shown in Table 2.

Patient Satisfaction by Mode of Results Delivery

In general, most individuals were highly satisfied with the delivery of their results, reporting an average satisfaction score of 3.6 on a four point scale (n = 135). Notably, there was no significant difference in satisfaction between patients who received their results over the telephone and those who received their results in clinic (Table 3 ). No other factors, including the type of result, whether a patient was tested for a familial mutation, or the length of the results session, significantly correlated with patient satisfaction.

We also queried patients as to whether they would have rather received their results in a different way (Table 4). Of the 51 patients who received their results by phone, 50 responded to this question and five of them (10.0%) indicated that they would have preferred to receive their results in person. Of the 82 patients who received results in person, 79 responded and 11 of them (13.9%) reported that they would have preferred to receive their results by phone. There was no statistically significant evidence that a preference for receiving results in a different way was associated with the type of result delivered (p = 0.51).

Patient Satisfaction by Time Waiting for Results

Patients were also asked to indicate how long it took for them to receive their BRCA1/2 genetic test results once they knew the results were ready by checking one of several options provided (see Appendix B). The amount of time a patient waited for results once they knew the results were ready was significantly related to their satisfaction (p < 0.001). Patients who waited 1 month or longer for their results were less satisfied than those who received their results in less time.

Patient Satisfaction Regarding Choice of Mode of Results Delivery

Those patients who had a choice of how to receive their results (those seen after 2005) reported a significantly higher mean rank of satisfaction (p = .024) when compared with those patients who reported not having a choice (those seen prior to 2005).

Lastly, cross tabulations were utilized to assess patient accuracy in recalling the result that was provided to them. Of the 136 individuals who reported a result, 132 (97.1%) accurately recalled their result. Four (2.9%) individuals, however, did not accurately recall their provided result. Three of these four individuals had received a result which involved a variant of uncertain significance. Of the four patients who did not accurately recall their result, three had received their results in-person (Table 5).

Discussion

Provision of BRCA1/2 genetic testing results by telephone is not rare among genetic counselors, but is provided to a minority of patients. The majority of counselors report that they deliver such results by telephone to less than 25% of their patient population. Even in exceptional circumstances, a large proportion of counselors would still never consider delivering these results by telephone. Although counselors are more likely to deliver negative (as opposed to positive) results over the telephone, the majority of counselors would still encourage patients to come into clinic to receive their results in all circumstances.

In our study, patients themselves exhibited no difference in satisfaction when their results were delivered over the telephone versus in clinic. These results are consistent with previous study results (Chen et al. 2002; Jenkins et al. 2007) and suggest that provision of results by telephone can be an acceptable practice in the setting of cancer genetics.

Two other findings were important with respect to patient satisfaction. First, patients who received their results within 1 week of knowing that their results were available were significantly more satisfied than those that had to wait a month or longer for their results. Thus, when dealing with a test like BRCA1/2 which often takes several weeks to be performed, providing results by telephone may be one way to increase patient satisfaction with the testing and counseling process. Second, our results demonstrate that patients who were given a choice of how they wanted to receive their results were more satisfied with their results session than those who were not given a choice. While the field of genetic counseling has focused on the pros and cons of telephone delivery of results, the current study suggests that perhaps the conversation should shift to discussing whether clinics should offer the option of how to receive one’s results instead of prescribing the mode of delivery. Such deference to patient autonomy is fully in keeping with the tradition of genetic counseling in which patient autonomy and choice have been of paramount concern. The results of this study support the notion that it is the autonomy to choose that impacts patient satisfaction, not the specific mode of delivery.

While the number of individuals correctly recalling the result provided to them is encouraging (~97%), it should be noted that a few individuals inaccurately recalled their specific result. However, as previously mentioned, three of these four individuals’ results were variants of unknown clinical significance. These variant results may have been reclassified since the time of initial results disclosure or deemed low enough risk to have been considered negative. Therefore, it is uncertain whether these three individuals actually inaccurately recalled their result. The fourth individual who inaccurately recalled the test results actually received a negative result but recalled having received a positive result. Again, it is unclear from the information we have whether this is an example of incorrect comprehension on the part of the patient or if, for example, the negative was considered to be a false negative. However, future studies aimed at investigating patient comprehension of variants of unknown significance may be warranted. While no firm conclusions can be gleaned from the four instances of apparent misunderstanding of patients regarding their results, it is worth noting that in three of the four cases of incorrect recollection, the patients had received results in-person.

This study found supportive results for the routine provision of BRCA1/2 genetic test results by telephone, and was designed to assess counselor practice and patient satisfaction with this mode of results delivery. However, there were a number of limitations to the current study. Counselor and patient response rates were not high (22.5% and 36.1% respectively), and therefore cannot be assumed to be entirely representative of these populations. Selection bias cannot be ruled out and the exclusion of African American individuals due to a concurrent study also limits the generalizability of results. Reliance on estimation and recall for both counselors and patients also limits this study since genetic counselors were asked to estimate past and present practices in regards to delivery of BRCA1/2 genetic test results by telephone. Patients were asked to recall their experiences with receiving their results, which in some cases occurred greater than 3 years ago. However, this specific limitation was addressed in the survey design by giving patients the option to answer ”unsure” to many of the questions, allowing those responses to be eliminated in data comparisons and analysis.

Another limitation of this study stems from the fact that some individuals received results before 2005 (those who were not given a choice in their results method) and were compared with a group of later patients who were given an option. Time-based factors could have affected patient satisfaction responses that were not related specifically to the mode of disclosure. However, the stable nature of the clinic and personnel throughout both periods of time should have minimized such concerns.

Conclusion

As genetics increasingly permeates medicine, genetic testing will become commonplace. It is critical that our field continue to explore optimal means of delivering results with an eye towards maintaining professional standards, accuracy and patient satisfaction, while at the same time seeking maximal efficiency. The results of this study suggest that results should be delivered as swiftly as possible once they are available, and that offering patients a choice of how to receive results is desirable. If future studies confirm that patients are more satisfied with choice, and that there is little difference in patient comprehension and retention of knowledge by telephone versus in person, then the option of results by telephone, perhaps with the option of a follow-up session if desired, should become the standard mode of delivery for most genetic testing results. Such considerations are of great importance as medicine struggles to incorporate an increasing volume of genetic data into daily practice while maximizing efficiency and appropriately caring for the increasing number of patients receiving genetic testing.

References

American Cancer Society. (2008). Cancer Facts & Figures 2007. Retrieved January 8, 2009, from http://www.cancer.org/downloads/STT/2008CAFFfinalsecured.pdf.

American College of Medical Genetics Foundation. (1999). Genetic susceptibility to breast and ovarian cancer: Assessment, counseling and testing guidelines. New York: American College of Medical Genetics Foundation.

Baker, D. L., Schuette, J. L., & Uhlmann, W. R. (eds). (1998). A guide to genetic counseling. New York: Wiley.

Chen, W. Y., Garber, J. E., Higham, S., Schneider, K. A., Davis, K. B., Deffenbaugh, A. M., et al. (2002). BRCA1/2 genetic testing in the community setting. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 20(22), 4485–4492. doi:10.1200/JCO.2002.08.147.

Helmes, A. W., Culver, J. O., & Bowen, D. J. (2006). Results of a randomized study of telephone versus in-person breast cancer risk counseling. Patient Education and Counseling, 64(1–3), 96–103. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2005.12.002.

International Huntington Association and World Federation of Neurological Research Group on Huntington’s Chorea. (1994). Guidelines for the molecular genetics predictive test in Huntington’s disease. Neurology, 44, 1533–1536.

Jenkins, J., Calzone, K. A., Dimond, E., Liewehr, D. J., Steinberg, S. M., Jourkiv, O., et al. (2007). Randomized comparison of phone versus in-person BRCA1/2 predisposition genetic test result disclosure counseling. Genetics in Medicine, 9(8), 487–495. doi:10.1097/GIM.0b013e31812e6220.

Klemp, J. R., O’Dea, A., Chamberlain, C., & Fabian, C. J. (2005). Patient satisfaction of BRCA1/2 genetic testing by women at high risk for breast cancer participating in a prevention trial. Familial Cancer, 4, 279–284. doi:10.1007/s10689-005-1474-y.

Lea, D. H. (1996). Southern maine genetics regional services program patient survey. Retrieved August 12, 2006, from www.nsgc.org/members_only/tools/pssurveys.cfm.

Middleton, L., & Rodriguez, G. (1997). Patient satisfaction survey. Retrieved August 12, 2006, from www.nsgc.org/members_only/tools/pssurveys.cfm.

National Cancer Institute. (2008). Cancer topics. Retrieved January 8, 2009, from http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/breast.

Ormond, K. E., Haun, J., Cook, L., Duguette, D., Ludowese, C., & Matthews, A. L. (2000). Recommendations for telephone counseling. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 9(1), 63–71. doi:10.1023/A:1009433224504.

Peshkin, B. N., DeMarco, T. A., Graves, K. D., Brown, K., Nusbaum, R. H., Moglia, D., et al. (2008). Telephone genetic counseling for high-risk women undergoing BRCA1 and BRCA2 testing: rationale and development of a randomized controlled trial. Genetic Testing, 12(1), 37–52. doi:10.1089/gte.2006.0525.

Petrucelli, N., Daly, M. B., Culver, J. O., Levy-Lahad, E., & Feldman, G. L. (2005). BRCA1 and BRCA2 hereditary breast/ovarian cancer. Retrieved April, 2, 2006, from http://www.genereviews.org.

Rhee-Morris, L. (2006). UC Davis Medical Group genetic counseling patient survey. Retrieved August 12, 2006, from www.nsgc.org/members_only/tools/pssurveys.cfm.

Schneider, K. (2002). Counseling about cancer: Strategies for genetic counseling (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley.

Trepanier, A., Ahrens, M., McKinnon, W., Peters, J., Stopfer, J., Grumet, S. C., et al. (2004). Genetic cancer risk assessment and counseling: Recommendation of the National Society of Genetic Counselors. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 13(2), 83–114. doi:10.1023/B:JOGC.0000018821.48330.77.

Young, T. (1993). Issues in quality assurance explored: is telephone counseling an oxymorom? Perspectives in Genetic Counseling, 15(2), 2–3.

Acknowledgements

This project was completed as a Capstone Project and could not have been completed without the support and guidance of the supervising committee, comprised of Lisa Susswein, MS, CGC, Chair, Nancy Callanan, MS, CGC, and James Evans, MD, PhD. Thanks is also warranted to the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill Cancer Genetics Clinic, the University of North Carolina at Greensboro Genetic Counseling Program & 2007 graduating class, Dr. Sat Gupta, Minna Wiley, and Jennifer Rittelmeyer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A

Appendix B

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Baumanis, L., Evans, J.P., Callanan, N. et al. Telephoned BRCA1/2 Genetic Test Results: Prevalence, Practice, and Patient Satisfaction. J Genet Counsel 18, 447–463 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-009-9238-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-009-9238-8