Abstract

Purpose

Historically, most research looking to improve services for domestic violence (DV) survivors has been designed based on the existing state of services, rather than using direct input from survivors. Building on this research gap, this study seeks to understand what “success” looks like for a broader and diverse population of survivors and service providers. Specifically, this study explored how survivors of DV, and service providers define “success” for survivors of DV. The researchers purposefully chose to keep the definition of success vague to allow participants to define what success is for themselves. This methodology aligns with the field shifting toward a survivor centered lens. Research questions guiding the study were: (1) How do survivors of DV define success? (2) Do themes for survivor-defined success align with service provider-defined program success?

Methods

Interviews and focus groups were conducted with 53 DV survivors and 13 service providers in a Midwestern state. Our study was informed by the Appreciative Inquiry methodology. Data analysis was conducted using constant comparative analysis.

Results

Seven themes emerged from the data: (1) acknowledging the process, (2) safety, (3) recognizing abuse, (4) therapeutic outcomes, (5) identity, (6) healing, and (7) achievement. Our findings indicate that survivors and service providers agreed on the major themes that were discussed related to defining success for survivors.

Conclusion

These findings can inform programs and services of the outcomes that survivors find truly meaningful and explore how those align with current service provider expectations. The outcomes identified can also be used to develop measures that can assess the impact that programs have on survivors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Decades of research have established that domestic violence (DV) has serious and long-lasting outcomes, including severe psychological trauma, financial instability, physical injury, and social isolation. Not only do survivors of DV experience trauma from the abuse itself, but they also face several barriers outside of the abuse that can amplify the adverse effects of DV such as lack of income, access to resources, discrimination, and poverty. These serious and negative outcomes can also impact survivors’ engagement with DV services for safety and healing (Flicker et al., 2012; Lipsky et al., 2005; Woods, 2005). Consequently, for survivors of DV, access to needed resources is crucial. In fact, gaining access to appropriate and quality resources can be a significant first step towards improved mental and physical health (Beeble et al., 2009) and autonomy to live a violence-free life. However, the extant literature also suggests that survivors of DV and especially those from marginalized populations rarely seek help or report their experiences to traditional formal sources due to concerns about the sensitive nature of the assault, fear of reprisal, and stigmatization (Liang et al., 2005; Vaughn et al., 2015).

Given the severe negative impact that DV survivors experience, a wide variety of services such as advocacy, shelter, legal support, and counseling have been established within the last 30 years to respond to DV (Sullivan, 2005). The main goal of services provided through these programs is to empower survivors and improve their health and well-being through understanding their current struggles and situations from multiple perspectives. Despite this, there is insufficient evaluation to know the impact that services are having for survivors. In times when funding is inadequate, it is especially important for organizations to perform evaluations to demonstrate which of their efforts are resulting in positive outcomes for their service users (Sullivan, 2011). Many service providers are still questioning how best to measure the impact of these services on survivors. This is because there are still no standard outcome measures to determine the impact that programs have on survivors who seek out services. However, a growing body of research is addressing this gap by developing and evaluating outcome measures that DV programs can use. One such research center is The Domestic Violence Evidence Project; a key initiative of the National Resource Center on Domestic Violence that assists those in the field such as service providers to “better respond to the growing emphasis on identifying and integrating evidence-based practice in their work” (see nrcdv.org and dvevidenceproject.org for thorough review). This project has compiled existing research and developed a Theory of Change to support the work of DV programs (Sullivan, 2012). It includes a look at key outcome measures such as the ones discussed in the following section.

Overview of Outcome Measures

Several researchers have had a particular focus on highlighting survivors’ insights and experiences as the bedrock for developing validated program evaluative measures. A good example of such measures is the Measure of Victims Empowerment Related to Safety (MOVERS), a measure that assesses survivors’ empowerment and safety when engaging with DV services. This measure was developed through collaborating with over a dozen different DV programs and by surveying over 200 survivors (Goodman et al., 2014). Similarly, Goodman et al. (2016) later developed the Survivor-Defined Practice Scale (SDPS), a scale that measures whether a DV service’s practices are centered on survivors’ needs. The SDPS was created in collaboration with researchers and DV programs. In the U.K., some researchers sought to better understand how survivors, perpetrators, funders, and practitioners defined success in all types of DV related services to develop accurate measurements of success (Westmarland et al., 2010). Additional research looking to improve services has centered on survivors’ tangible needs (Lyon et al., 2012), barriers to help seeking (Fugate et al., 2005), and helpfulness of services (Zweig & Burt, 2007). Goodman et al. (2017) continue to recommend that researchers focus more on asking survivors about the most meaningful outcomes from programs. There appears to be a large gap in survivors’ involvement in the process of outcome development because most of these studies were designed from the perspective of the existing state of services as it evolved rather than from the direct input from survivors. None of the existing studies included survivors without any predetermined conceptions about what “works” or what “success” looks like for programs.

For studies that have examined “success” from the perspective of the survivor, one report asked survivors to describe what “success” generally looks like for them (Melbin et al., 2014); however, they did not relate the responses back to outcomes from programs. Another report (Westmarland et al., 2010) also sought to describe success; however, the report looked only at perpetrator programs, rather than the broader spectrum of services for survivors. Consequently, this study seeks to broaden the scope of the methodology of both projects and explore what “success” looks like for a broader population of survivors and service providers and relate it directly back to program outcomes.

The added benefit of this approach is that it fits within the trauma-informed care model (Kulkarni et al., 2015). Specifically, we sought to develop outcomes collaboratively between survivors and providers, empowering each to use their voice to impact program change (Cattaneo & Goodman, 2015). Survivors’ perspectives of their own goals/successes, what aspects of DV programs are efficacious, and what aspects need improvement are essential in adequately evaluating the impact that a program has. This is not only because survivors have a unique viewpoint due to their social location, but also because many DV programs follow a model of empowerment, in which clients are considered the most knowledgeable about their own needs and thus should be able to guide their own plan to success (Sullivan, 2011). Empowerment models also stress the importance of promoting self-efficacy in survivors because of its strong association with outcomes (Cattaneo & Goodman, 2015). Survivors are empowered when they can accomplish their goals by themselves, or through collaborative relationships. While many programs believe that they are following an empowerment model, scholars and advocates have noticed that the strict policies and predetermined definitions of success can recreate the abuse experienced by survivors (e.g., Goodman et al., 2017). While collaborative relationships are essential in any therapeutic relationship it is especially important for those healing from the impact of domestic violence. Survivors of domestic violence have often experienced a loss of agency in their lives. Therefore, survivors should also have a significant role in guiding the understanding of what a successful DV program would look like.

It is also worth noting that DV research has historically suffered from mainstream biases and conventional sampling. The solutions that are used for mainstream populations often do not work for marginalized or minority populations and at times they can be more harmful than helpful for these populations (Goodman et al., 2016). Thus, it is imperative to utilize innovative approaches to be inclusive of populations that are not typically sought for research and/or are not typically seeking DV services due to cultural factors and other barriers. Most research is conducted by academic researchers and without the input of community stakeholders. When community stakeholders are involved in the research process, it builds ownership, generates more valuable data, and increases effective dissemination of study results (Hausman et al., 2013). For that reason, the researchers in this study worked with a specific community “Family Violence Research Collaborative” to ensure the findings reach those who are directly impacted.

Study Purpose

Therefore, building on the above research gap, the main purpose of this study was to compare and contrast definitions of “success” from the perspectives of populations impacted by DV across a Midwest state, with a special focus on populations underrepresented in research and services. The goal is to inform programs and services of the outcomes that survivors find truly meaningful and explore how that aligns with current provider expectations. It is expected that these outcomes can be used to develop measures in the future, to identify the impact that programs have on survivors. The study was guided by the following research questions: (1) How do survivors of DV define success when accessing DV services? (2) Do themes for survivor-defined success align with provider-defined program success? Due to the importance of being survivor-centered and the exploratory nature of this unique study, the research team did not have explicit hypotheses about themes that might be found or how much those themes might align between survivors and providers. The goal was to set up a study design that would allow as close comparison between participants so that any themes and their similarities or differences would be natural and not a result of the questioning.

Methods

Research Design

The Family Violence Research Collaborative was created to address the gaps between research and practice found in the field of family violence. This group consists of researchers, practitioners, evaluators, and stakeholders that seek to contribute to the advancement of the field. During initial meetings many practitioners and stakeholders identified a need to understand how to measure relevant domestic violence program outcomes. A subgroup of members was formed to develop the design of this project, including evaluators, researchers, a focus group consultant, a service provider, and a representative from a statewide DV coalition. The Principal Investigator (PI) consulted with other DV service providers in the area to ensure safety and culturally specific feedback and the final design was discussed with the larger Family Violence Research Collaborative to ensure its implementation would support the expected goals of the project. This study was approved by the authors’ Institutional Review Board.

The study utilized a concurrent mixed method approach to better understand expectations for DV programs success. In using this research design, both qualitative and quantitative data was collected simultaneously, allowing for perspectives from survivors and service providers when analyzing the data. The current findings are focused on the qualitative data from this project.

Participant Recruitment

A convenience sampling technique was used to recruit study participants. Survivors had to meet the following criteria to be included in the study: (a) 18 years of age or older, (b) current or past victim of DV (defined as an adult who has experienced physical, sexual, and/or emotional abuse from an intimate partner or family member) (c) not the primary aggressor in the abusive relationship, (d) no safety concerns for participation, (e) participant felt they could discuss the subject in a research (not counseling) context, d) participant felt it was safe to attend a focus group/interview, e) participant could come up with a feasible cover story for whereabouts for partner/family, (f) partner was not currently stalking or recently threatened to kill participant, d) participant agreed to safety and confidentiality rules of the focus group to keep all participants safe. For providers, the following inclusion criteria was used: (a) 18 years of age or older, (b) current or past service provider working in an agency that serves victims of DV (defined as an adult that has experienced physical, sexual, and/or emotional abuse from an intimate partner or family member), (c) no safety concerns for participation, (d) participant felt it was safe to attend a focus group/interview, (e) participant agreed to safety and confidentiality rules of the focus group to keep all participants safe. Study participants were recruited using different mechanisms. A variety of service agencies were approached by the Principal Investigator (PI) to discuss the potential to post the recruitment flyer that outlined the details of the study. A phone number was also included in the flier so that potential study participants could reach out to participate in the study. The PI also approached local businesses to request posting the flyer on public boards to recruit participants. The PI also sent emails to provider agencies or existing provider networks (with approval) to recruit provider participants. Key study staff also reached out to individuals in organizations that they had a connection with.

Individuals interested in participating in the study contacted the research team member by using the telephone number on the flyer. The research staff used a screening guide to determine eligibility for the study, provide local service/resource contacts as indicated, and schedule the participant in the appropriate interview (survivors or providers interview). During screening, we utilized a screening questionnaire developed by the study team to ensure inclusion criteria. This included asking questions about control and power in relationships, whether the caller had experienced DV in its various forms, and questions to address safety. The questionnaire was developed alongside DV intake experts in multiple agencies, enhanced by trauma-informed knowledge and research, and vetted by DV providers. The answers were mainly yes/no, with very limited open-ended responses to limit traumatic storytelling. Also, any caller that was screened was offered resources to connect with, even if they were not included in the study.

Participant Demographics

Survivors

Fifty-three DV survivors participated in either focus groups or individual interviews. The age of the survivor participants ranged from 21 to 71 (M = 45.05 years, SD = 13.27). Regarding gender identity, 52 survivor participants identified as cisgender women, and one participant identified as a transgender woman. In terms of race and ethnicity, 28 participants were white, 14 were African, five were African American, three were Hispanic or Latino, one was American Indian, one was Asian, and four identified as other. Eighteen of the 53 survivor participants were immigrants or refugees. Regarding sexual orientation, 28 survivor participants identified as heterosexual, one identified as lesbian or gay, three identified as bisexual, and four identified as other. Eleven of the survivor participants did not have any children, seven had children all over the age of 18, and the other 35 had children under the age of 18. Ten survivor participants were from rural areas, 16 were from urban areas, and seven were from a suburban location.

Providers

Thirteen providers participated in either focus groups or individual interviews. The age range of these participants was 22–57 (M = 37.00, SD = 11.16). Twelve identified as cisgender women and one identified as a cisgender man. Six provider participants identified as heterosexual, two as lesbian or gay, one as bisexual, and two as other. Eleven of the provider participants were white and two identified as Hispanic or Latino. Two of the provider participants shared that they were immigrants. Six of the provider participants worked in urban settings, three in rural settings, and four in suburban settings. In terms of their specific occupation, four were case managers, two were counselors, seven were advocates, one was in law enforcement, and four were in management. The provider participants had a variety of experience in the field, ranging from less than 1 year to up to 20 years of experience.

Instrumentation

The research team worked collaboratively to develop the design and measures of this project, discussing validity in regularly scheduled meetings. The interviews were semi-structured to guide the conversation and addressed the main research questions. Guided by the Appreciative Inquiry methodology (Cooperrider & Suresh, 1987), researchers asked participants about how they define success and their experiences of success within current DV programming. Researchers also invited participants to dream about what program success should look like for survivors and discussed enabling factors that can support a survivor towards their visions of success. Additional probing questions were also included to help delve into the issues discussed. After the qualitative interviews were complete, participants were invited to complete a brief survey regarding the following: life satisfaction, relationship satisfaction, hopefulness for the future, service utilization, trauma event history, and other demographics.

Data Collection Procedure

Focus groups and individual interviews were used for data collection. For the focus groups, participants were checked in and had assigned seating with assigned coded numbers so that no names were utilized during discussions in the interview room. Seats were pre-set with a clipboard that included the interview materials such as informed consent. Snacks were made available and participants had the opportunity to relax until all expected participants were in the room. Following informed consent and agreement with group rules, participants were then guided through the relevant Appreciative Inquiry script (Survivor script for survivors, Provider script for providers). Following the qualitative interview, the facilitator introduced participants to the supplemental survey questions. The entirety of the session lasted about two hours. Upon completion of the interview, participants were provided with a gift card with an appropriate amount based on related DV research for their time and travel. An interpreter was also used for focus groups with participants that were non-English speaking.

The individual interviews were conducted both in-person and on phone. The in-person interviews followed the same protocol as focus groups except that: (a) no ground rules were necessary, though the researcher reminded the participant to exclude typical identifiers (e.g., names) from the conversation, (b) providers were offered the choice of a phone interview, in which they would correspond by email to set up a time. The phone interviews were the same as in-person except that: (a) consent was given verbally; (b) for the convenience of the phone interview, participants did not receive a free meal; (c) the supplemental survey was completed via REDCap; and (d) the gift card, along with a blank copy of the consent form, was mailed to the participant. Interviews were all audio recorded and transcribed for analysis.

Data Analysis

The coding of themes was undertaken using constant comparative analysis: (1) thorough reading of all interview transcripts, (2) open coding – to label concepts, define categories, and assist in the interpretation of data (Emerson et al., 1995), (3) axial coding – to relate and/or combine codes together into categories (Leech & Onwuegbuzie, 2008), and (4) selective coding – to determine core themes for comparative analysis for the specific research questions (Emerson et al., 1995; Leech & Onwuegbuzie, 2008). Additionally, we ensured credibility of our findings providing verbatim transcription, demonstrating saturation, reviewing related literature, and member checking with willing participants (Whittemore et al., 2001).

Supplemental measures were used in frequency analyses to gain understanding of the violence-related characteristics and demographics of participants. Though outside the scope of this current paper, developed themes were then used in conjunction with supplemental measures to determine differences by cultural affiliation, as well as to compare survivor-defined success and provider-defined success.

Results

Themes

Upon examining how DV survivors and providers define success for survivors, seven themes emerged from the data. Table 1 provides a summary and percentage of themes from the participants.

Theme 1: Acknowledging the Process

One theme of success for DV survivors was the ability to “acknowledge the process.” This was defined as the ability to recognize that success is a journey, and often a long one. Survivors and providers discussed the necessity of a survivor recognizing from the start that the process of success will be lengthy and difficult, and deciding nonetheless to take steps forward, even if they do not know where those steps will lead. In support of this a provider participant from the Appalachian region, with 3 years of experience in the field, explained that: “I guess—taking the first step, even if you don’t know what the second or third step will be.” A divorced survivor from an urban area affirmed this sentiment by stating that: “I mean healing is a lifelong process from domestic violence. It comes in waves.”

In addition to recognizing the long journey, survivor and provider participants also spoke about the importance of the survivor themselves deciding to reach out for help, as one provider participant stated: “They say picking up the phone weighs 1,000 pounds and all that kind of stuff.” A divorced survivor from an urban area also spoke to this by stating that: “And in order for them to get the help they need, they have to come out of denial that they need help. And I think that is something that the individual has to come to terms with.”

Providers and survivors alike affirmed that asking for help is often incredibly difficult as one 30 year old survivor interviewee from a suburban area described: “That first step is incredibly hard for a lot of people, especially if you’ve been with ‘em for a long time. That’s all you know.”

Finally, participants discussed that survivors must acknowledge that their journey to healing and success will be filled with setbacks and difficulties. A Puerto Rican provider put it this way:

The recognition that it didn’t take them overnight to get here and it’s not gonna take them overnight to heal. To know that sometimes they’re gonna go three steps forward, and sometimes they’re gonna go four steps back. That’s all part of their healing journey.

A 35 year old survivor participant from an urban area affirmed this sentiment as well:

It’s a long process, and god it’s been long. It’s like, I still can’t believe how long it takes to get better and the things you have to go through to start even becoming the woman that I should be, or that I think I should be.

Theme 2: Safety

The second theme that emerged was the importance of safety to survivor success. At the most basic level, this means a safe place to live. A 42 year old provider with 10 years experience in the field explained: “Safety first. If she has to relocate, if she has to go into shelter, live with family, friends, making sure she’s physical safe and then mentally safe.” Not only is a physically safe environment a component of success, but participants also discussed the importance of having a safety plan. Another provider stated: “I would say, and it really comes down to learning more ways to plan for their safety.”

Participants also discussed the importance of internally feeling safe and secure. A 53 year old divorced survivor participant from an urban area made the connection between feeling safe and being able to heal: “Just to feel safe. A person has to feel safe in order to get healing.” Later this same participant added:

I think in the early stage the best thing is safety you know? You need to be safe. You need to be able to be in a space where you’re safe. And I don’t think that you’re going to be able to be contacted by this individual or found by this individual so that way I can grow and heal.

Another survivor participant from an urban area confirmed this point: “They need to know that there’s a safe environment so that they can help themselves.” Part of this emotional safety results from freedom from the toll an abuser takes on the survivor. A provider participant with 16 years in the field explained: “Feel safe to do any of these things without having consequences or worry about how that’s gonna—how they can do that without that person judging them.”

Theme 3: Recognizing Abuse

The third theme was that recognizing abuse is a component of survivor success. One aspect of this is recognizing signs of abuse, which participants explained is very difficult. A 53 year old divorced survivor participant from an urban area described it this way: “It takes years to even realize that you’re picking these men that are domestically violent. The awareness of that in itself sometimes takes years.” Many survivor participants explained that it was not until after treatment that they were able to recognize these signs as one survivor participant shared:

I still am in shock about a bunch of things. I did not know until I went to the support group what domestic—all the domestic violence. How it can be everything, financial, controlling. I thought domestic violence was actually physically getting hit and harmed. When I learned all that, then I was shocked. I was like, “I can’t believe that girls aren’t educated—anyone—I shouldn’t just say girls—anyone’s educated. They don’t teach this in school so it can stop. Slow down. You have the warning signs. Get out of it.”

In addition to recognizing signs of abuse, participants also discussed the success of a survivor no longer accepting these abusive actions; realizing that abuse does not have to happen, it is not deserved, and it is not permissible. In some cases this involves completely leaving the abusive partner, as one 36 year old single survivor participant from an urban area described:

I went to a homeless shelter because I was just done, and um, I wanted to depend on myself, and I had courage and strength and it was just different, I wasn’t going to stand and put up with that, and it just, something in me just decided to go.

A provider participant also discussed a similar situation where a survivor developed this courage by stating: “I can’t think of a better word, but she was so empowered that she was like, I’m gonna get divorced. This is what I’m gonna do. No one can stop me now”.

Part of recognizing abuse also relates to the ability to face what has happened in the past and deal with the impact of abuse. Sometimes this means getting angry, like one 44 year old survivor participant from an urban area explained: “You weren’t allowed to be angry with your abuser. Now you can be angry about things that you don’t like.” In examining the impact of the abuse, survivor and provider participants also spoke to the importance of survivors learning to forgive themselves and getting rid of self-blame, as one 30 year old survivor participant from a suburban area stated: “To realize that it’s not their fault, and that it’s not really anyone’s fault, but the person who abused them.” Similarly, a 42 year old provider participant with 10 years in the field shared that a successful survivor would be able to understand: “I’m not a bad mom. I’m not a bad person because I stayed with this person for so long.”

Theme 4: Therapeutic Outcomes

The fourth theme that emerged were codes of a “therapeutic” nature; speaking to the importance of survivors experiencing relief of mental health symptoms, building coping skills, learning to take care of themselves emotionally, and gaining sobriety as components of success. In regard to relieving mental health symptoms, a 53 year old survivor participant from an urban area discussed experiencing some relief from prior trauma: “And now um I’m not haunted of nightmares from my past.” Another 24 year old survivor participant from an urban area also described a change in their mental state:

I know I feel more motivated to do things. I can definitely see where I was lacking a lot of motivation to do things. I didn’t ever really wanna get up and do anything. I wanted to lay in bed all the time. I know this sounds really bad, but there was a point in time where I didn’t really wanna be around my kids. I just felt so groggy. I felt like I was never good enough for anybody. Once I got rid of that burden on my shoulder, it feels so much better. You get a spurt where you’re just a bunch of energy.

A 43 year old provider participant with 16 years in the field spoke to this as a component of success as well: “Letting go of sadness or depression or overcoming that loss, grief.”

Participants discussed the importance of survivors building coping skills in treatment as one 34 year old immigrant survivor participant from an urban area mentioned: “Essentially, by the time you leave, you have the skill sets you need in order to be the best version of yourself.” A 24 year old provider participant discussed how an essential coping skill is learning to think more positively:

Unfortunately, in order to accept what has happened to them, sometimes they do have to look at the negatives, but in the same hand also trying to focus not solely on the negative, but on the positive. I found that the people I’ve worked with who have been able to rebuild a lot their lives are the ones who were able to separate the negatives and the positives and be able to have a healthy balance of it.

An important factor in survivor success that was discussed in the focus groups and interviews is relief from substance abuse issues that are often tied to DV. One 35 year old survivor participant from an urban area shared that part of their healing process involved getting sober: “Yeah, um, I became sober. Yeah, so that was a big step too, I mean there was a lot of changes all at once.” Another 33 year old survivor participant from a rural area explained how sobriety is important for true healing: “There’s substances that also numb—it’s all about numbing the pain, and so reconnecting to who you are as a person and working towards things you want that are healthy and obtainable.” A 42 year old provider participant with 10 years in the field spoke to this as well: “Then if they have drug abuse on top of it, obviously, getting and making sure those areas are covered as well and see the connection between domestic violence and substance abuse or mental health.”

Theme 5: Identity

The fifth theme related to survivor success is “identity.” This theme is important because in the abusive context, the abuser holds all the power and the survivor is reliant on what the abuser has told them. Survivor success therefore includes the survivor learning to express their individuality, gain autonomy, make their own decisions, and choose their own way of doing and being. A 48 year old survivor participant from an urban area described this: “Taking back a part of myself that had been taken away from me.” Another 44 year old survivor participant from an urban area also spoke to this:

I had lost my individuality. It’s like my favorite color is yellow, but I don’t own any yellow clothes, or I could eat spaghetti every day, but we don’t have spaghetti for dinner. You know what I’m saying? I lost who I was because there was one point when I just told my abuser—I said, “I know I can’t take this anymore because I’m becoming just like you.”

A provider participant talked about boundaries as an important component of a survivor’s individuality: “Boundaries is a big one. Setting up boundaries. Saying ‘no’ and it’s okay. It’s okay to say, ‘No, I’m not gonna do this,’ or ‘I’m not gonna go here or do this.’”

One important element of identity is survivors discovering hobbies and activities they truly enjoy. One 48 year old survivor participant from an urban area put it this way:

You have to find something that is truly something you enjoy for you, not for anybody else, because how long did we have to do this because that is what somebody else wanted you to do, you know find something that you truly enjoy whether its painting, or reading, or knitting.

Another 44 year old survivor participant from an urban area described the freedom that came from being able to make their own choices based on what they enjoyed: “Hobbies and interests that I wanted to do but didn’t get to. Places I wanted to go, things I wanted to do, I was able to then. It felt like being free. It felt like coming out of prison.”

Another component of the theme “identity” is the change in personal appearance survivors often experience. A 50 year old survivor participant from a suburban area said this was personally true for them: “I look 10 years younger a year later, like a completely different person. When I look at that, my skin, my eyes, I just look—I did not see that.” A 29 year old provider participant described this change as well, and spoke to why it occurs: “I feel like a lot of people do carry that burden physically in their bodies. You might be able to see that change in confidence, or change in optimism in their bearing, and like how they dress themselves.”

Theme 6: Healing

The sixth theme that emerged was “healing.” This includes survivors experiencing feelings of hope, happiness, gratitude, freedom, and peace. Several survivor and provider participants described these emotional states as characterizing successful survivors. One 50 year old survivor shared the lightness she experienced: “I was just like, Oh, my gosh. Life is so good. I am so happy. [Laughter] This is so much better.” Another 39 year old survivor from an urban area talked about their gratitude: “So I was thankful for everything… I was…I’m more…I was humbled.” They also discussed the freedom they experienced, as one 23 year old survivor noted:

Yeah you just always seem to, you know when you are in a relationship, abusive relationship you just, you know, you show your gloom and doom. And when you’re out of it, when you’re free, that exactly how it feels, free, I am free of this.

A 71 year old divorced survivor participant from a suburban area described the hope they felt: “To be able to feel that perhaps you might have a happy ending.” Another 48 year old survivor participant from an urban area also talked about the peace they had gained:

Peace. To know peace. Because when you live in a situation like that there is no quiet, there is no peace. You are always tip toeing around, walking on eggshells, if you’re home a half an hour before him, you’re on edge, you know that lack of peace, and I think all of us know that feeling.

Another aspect of healing is feeling that justice has been served. A 57 year old provider participant discussed this: “And that justice is possible, although difficult. It is possible for them to incarcerate their husbands or perpetrators.” A 39 year old survivor participant from an urban area shared their own experience of justice:

To have a judge look at you and say, “Congratulations” when you’re divorcing a terrible person, that felt—I will never forget that moment. He [her abuser] sat there looking dumb. He was like, “Congratulations for you and your daughter. Awesome job.” I was like, “Yes.”

Finally, participants discussed how part of healing is gaining a sense of self-worth and confidence. Survivors talked about being able to view themselves as victorious for surviving what they had been through, and seeing their dignity and worth. A 62 year old transgender survivor from a rural area shared how they had learned to build their self-esteem:

Just wake up and be like ahhh I’m wonderful. I’m special. I’m unique and I’m rare. You know… I tell myself that every day. There’s nobody who could touch that, you know. Because I had to tell myself that because for so many years I was told just the opposite.

A 22 year old provider discussed this as well:

The ability to see their higher self-esteem, higher self-worth, confidence in their abilities and trust in their instincts. The ability to see what they are capable of. What they’ve done to survive up to now shows the strength they have developed… A lot of times, survivors feel like they’re weak because they feel—because our society is so stigmatizing and so blame—victim blaming. For them to see that they’re really the strong ones in the relationship. What they’ve gone through is just astronomical and phenomenal.

Theme 7: Achievement

The seventh and final theme to emerge was “achievement.” This achievement has many facets, including obtaining an education and a career. A 30 year old survivor from an urban area talked about the independence getting an education granted them: “I didn’t even finish school. Now, I feel like I can finish school, and I can be somebody, and I can provide for my daughter. I don’t need him anymore.” Another 44 year old survivor from an urban area shared their entrepreneurial aspirations: “I’m starting my own business.” A 44 year old provider participant discussed this importance of this area as well:

I feel like half my caseload, they are dealing with all kinds of stuff, and what they really want is a job. There’s this laundry list, but what would help me right feel better about myself—feel like I’m a contributor, that I can get out of the situation—everything could be handled with a job.

In addition to achievement in education and career, another aspect of achievement is being able to fulfill social roles. This includes being a good employee, but also includes familial roles such as being a good parent. A 30 year old survivor from a suburban area described what this looks like: “They’re doing housework. They’re taking care of the kids. They’re cooking. Whatever their normal life looks like that they’re doing it is really a good indicator that they’re going to be all right.” A 43 year old provider participant with 16 years in the field also spoke to this: “Trying just to live their life, doing the things that we have to do. Wake up and keep a schedule and take care of the family.”

Achievement is also manifested in being able to help others. A survivor participant talked about their desire to help others as reported by an interpreter:

She says that for instance, the community, after helping her, that they would learn from her experience that in the future they can help other women or other people having the same experience, and also even herself. She would be advocating for other women who are going the same situation, and she’d be guiding them, so that’s just advocacy.

A 22 year old provider participant shared how rewarding it is to watch survivors help other survivors: “Seeing her empower the other women that were on the table that day, I feel, was amazing.” Another 49 year old provider participant also had the same impression: “I think the coolest thing is showing up on scene with a victim you’ve had before and you’ve got someone else that’s new there, and that person saying, ‘I told them to call,’ or I told them.”

Another facet of achievement is survivors finding their passion. This can relate to their education and career goals, or it can be entirely separate. A 33 year old survivor participant from a rural area discussed the importance of being able to decide for themselves what they wanted to do in life:

It’s like figuring out what they want for them. Those are two things I want for me. A program can’t tell me what I want for me. Figuring out what I want for me—I have goals that I work towards and also recognizing what I want my life to look like.

A 44 year old provider participant talked about their desire for job training for survivors that is tailored to their passions: “Yes, employment resources that just don’t just funnel them into food prep, cutting things in a back room. I actually want to find out, ‘What is it that you want to do?’” Another 27 year old male provider participant affirmed the importance of helping survivors recognize their passions: “I feel like they might be able to re-find a purpose in life, you know?”

Survivor and provider participants also discussed how a survivor’s success and achievement would result in success for their children. A 51 year old survivor with three children shared their own experience with this and others seeing a positive change in her kids:

My sister told me, a couple weeks ago, that she was shocked at the change in my kids and myself in that she said, “That the tension in your house must’ve just been through the roof,” because she’s like, “Your kids are kids now, and they’re laughing, and they’re playing, and they’re moving away from you,” And that’s why I did it.

A 57 year old provider described other markers of positive changes in survivors’ children:

When they start getting good grades. That’s perfect. Yeah. That’s perfect because most of the time, they [survivors] can’t help with that because they don’t have an education. They feel like, “I can’t help my kid with school stuff,” but when their kids start getting good grades, that’s a good sign as well. When they have friends—they start getting friends—that's a good sign.

A 22 year old provider participant added: “The children will be able to start to maybe feel a little bit safer, hopeful.”

A final aspect of achievement for successful survivors is becoming independent and no longer needing to rely on others for help. A 44 year old survivor from an urban area described the change they experienced in themselves:

I felt like I wasn’t underneath. I felt like I was on top. It put me in control of myself, and I could better make decisions. I wasn’t doubting myself so much. I started becoming me again. Maybe that sounds strange.

A 43 year old provider participant with 16 years in the field described a successful survivor as: “They’re not asking for help all the time. Doing it on their own. They’re making it.” A 41 year old provider participant with 12 years in the field discussed how services should be designed in a way that fosters independence and not dependence in survivors: “I think equipping that person. I just think of it as a bridge, like a temporary bridge, providing the resources that that person needs in the interim to get her over to the other side of self-sufficiency.”

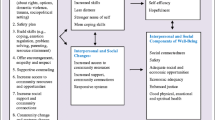

In examining these seven themes, it is noteworthy that these aspects of success do not necessarily have to occur in this chronological sequence, but there is an element of time involved. Some of these forms of success need to happen first before others can occur, and some are more related to short-term work, intermediate outcomes, and longer-term outcomes. A summary of these themes and the individual codes is displayed visually in Fig. 1.

Discussion

The main goal of this study was to explore how success within domestic violence programs is defined from both the perspectives of survivors of DV and providers of DV services. Guided by the appreciative inquiry model, we were able to learn about what survivors and providers thought was most essential for success and healing. Seven themes emerged from the focus groups and individual interviews with participants. The themes that emerged ranged from having basic resources for safety and being able to explore one’s own identity outside of their abusive relationship. These themes center the survivors’ ability to learn and grow from their traumatic experience. The findings of this study are unique and make a significant contribution on how a broad population of survivors and providers define success related directly to program outcomes.

Our findings indicate that survivors and providers agreed on the major themes that were discussed related to success for survivors. They both stressed the importance of safety, recognizing abuse, therapeutic outcomes, identity, healing, and achievement. Though providers and survivors agreed on the larger themes, there were some differences on which of the aspects of these themes they found most important. For example, both survivors and providers were quoted in the recognizing abuse theme, though providers tended to say more regarding recognizing the impact of the abuse whereas survivors tended to say more regarding the courage and strength to persist nevertheless. The similarity found in this study between providers and survivors is slightly different from Melbin et al. (2014) who found that survivors and providers were not aligned in their definitions of success. For example, in their project, survivors were less likely than practitioners to emphasize leaving the abuser as a key for success and were more focused on general successes not related to the abuse. Contrasting that, the practitioners they spoke with were more likely to focus on leaving the abuser and the role of formal services in facilitating success for survivors. The differences that they found are likely a product of the design of their project: survivors discussed success broadly and providers discussed success for the survivors with whom they worked (thus putting their responses in a context of service provision). In this study both survivors and providers were focused on success directly in relation to program outcomes.

One of the principles of trauma informed care is that it empowers clients to be a part of their healing process (DePrince & Gagnon, 2018). Through this approach clients and providers work collaboratively to achieve the client’s goals. Our findings also show that survivors and providers both recognize that securing safety is the beginning of the healing journey. This usually includes safety planning in case the person finds themselves in danger or learning about other safety measures that they can take proactively. Providers often mentioned how it was important for them to give survivors the tools they needed for their safety, while also respecting their autonomy. Survivors spoke about how they would not be able to talk about the trauma they experienced if they knew that there could be violent repercussions from their abuser.

Another important finding that emerged from our study was that both survivors and providers shared about the importance of having positive therapeutic outcomes as a component of success. This is connected to the healing process because survivors experience relief of mental health symptoms, build positive coping skills, learn to take care of themselves emotionally, and gain sobriety. All these are great skills that empower survivors and provide them with tools to navigate their daily lives even post-therapy while also ensuring that they are empowered to deal with difficult situations when they arise.

Most often, survivors of DV suffer from manipulation, power, and control from their abusers and this can result to a lack of confidence, low self-esteem and self-efficacy, lack of identity, and so many other negative aspects that can derail a successful life. It is therefore important that survivors and providers associated the aspect of one’s identity with success. Identity is empowering and strength-focused as the survivor can learn to express individuality, gain autonomy, make their own decisions, and choose their own way of doing and being. Survivors also desired to achieve different things in life such as obtaining an education and a career, becoming independent, being able to fulfill their social roles such as being mothers, and being empathetic to individuals going through similar challenges.

Taken together, these themes seem to generally align with program outcomes on the National Resource Center of Domestic Violence’s Conceptual Framework (Sullivan, 2012, updated 2016). The few minor exceptions include that survivors and providers in the current study did not focus specifically on the mother-child bond though they did identify other characteristics of success related to their children. Additionally, access to community resources and increased support/community connections were not defined as success but rather seemed to be included as factors that enable and enhance success. Taken altogether, this alignment is telling. These findings provide concrete evidence that survivors’ hopes for change are aligned with existing program structures; and measurement of this success would bolster evidence for program impact from both theory and directly by those that benefit from these programs – survivors themselves.

Implications for Research, Policy and Practice

Our findings have several implications. First, the factors that constitute and define success from both the perspectives of service providers and survivors can be improved with targeted interventions (Sullivan, 2006). These factors of success also provide information that can help to measure success outside of the scope of the absence of violence. One of the crucial barriers to improving DV services is a lack of validated outcome measures that assess whether the programs’ and the survivors’ goals are met. Outcome measures can help DV programs better understand their impact on survivors, which aspects of their program are most efficacious, and where best to allocate funding. Without adequate outcome measures, programs are given the burden of reporting numbers for grant requirements without any material benefit for the programs themselves or the clients that they serve. Programs can also use these measures to improve the quality of services more immediately and provide more informed summative evaluations of programs. This can lead to a better sense of how to create evidence-based practice standards for DV programs. These results can help funders to better identify the impact of their grant support. Perhaps most importantly, this all is of benefit to survivors. It allows better access to efficient and effective services. Moreover, when used as a clinical tool, the results from outcome measures allows the survivor the ability to see their own individual progress and success.

Our findings identified factors of what success looks like from a diverse sample of survivors and providers of DV. These findings can be translated to create outcome measures that assess individual program outcomes that are informed by the perspectives of those who matter most and those who mostly benefit from DV services, that is survivors of DV. Future studies should therefore explore how to incorporate such factors that define success for survivors when assessing or measuring the outcomes of their services. Such studies should also contextualize their measures based on the populations that they serve. In this study, we reported our findings of success in aggregate; a next step will be to explore in depth if there were any differences in the definition of success based on the different demographics of survivors and providers, such as race, immigration status, age, social location, administrative roles of providers, and so forth. Such information would contribute towards building outcome measures that are tailored and targeted for different populations and ones that capture the unique experiences of success based on individual worldviews.

Trauma informed and empowerment frameworks with survivors of DV should capitalize on survivors’ interpretations of success as defined by survivors and service providers in this study and how this impacts their well-being in the long run. In addition, the way survivors define success can change depending on what is happening at particular times in their life. The definition of success can therefore be seen as a process that includes different outcomes at any given point in an individual’s life. It is, therefore, vital to use longitudinal studies that help provide more evidence to test different ways that women define success for a given period based on different circumstances in their life.

Developing successful program outcomes will entail collaboration with researchers, program providers, funders, and policy makers to conduct extensive research that can improve survivor centered programs that recognize the unique ways that survivors define success and how this can be reflected in policy and training. Such strategies should be grounded in the principles of strengths-based policy making processes that seek to enhance the strengths and resources of individuals’ environments to help them better achieve their goals (Saleebey, 2006). One major strength of this study was that it was collaborative in that researchers collaborated more closely with survivors of DV and program service providers to ensure that the questions posed for the study were more meaningful questions and aimed to produce knowledge that can be useful to the providers and participants that these programs support. This collaboration is important as it helps to identify and prioritize aspects of program outcomes that are most important for survivors and program providers. This can also ensure sustainability of programs and improve well-being for survivors because they are closely aligned with what is important when measuring success.

Goodman and Epstein (2005) state that “one of the key questions facing researchers regarding DV in the coming decades is how the real-life experiences of survivors should affect state policy” (p. 149). Results from this study echo a similar perspective in that there is need to look at how survivors define success from their own perspective and in their unique contexts. Unfortunately, our criminal justice system and funding mechanisms from the government and other stakeholders has not been designed in a way that can help programs improve the way survivors and providers evaluate success. For example, within the criminal justice system, there is more focus on arresting and prosecuting the perpetrator over survivor empowerment (Goodman & Epstein, 2005). In fact, as discussed in the introduction section of this study, there are still a limited number of studies that focus on understanding the experiences of success and what success looks like from the perspectives of survivors and service providers. Therefore, findings from this study emphasize the need to increase such studies. In addition, grant agencies have an opportunity to better align their expectations with survivor expectations; and to better fund evaluation of programs.

Limitations

Because of the qualitative nature of this study, it is noteworthy that results are potentially not generalizable to a broader population beyond the participants in this study. Though saturation was met for survivors that attended interviews for this project, there is a potential for recruitment and self-selection bias. For example, though the large majority of survivor participants responded to recruitment from outside of formal DV services (e.g., from flyers in broader community locations), all but one survivor had been engaged with DV services at some point in their lives. Despite many survivors of DV never engaging with services in their lifetime, researchers have historically struggled to recruit these survivors and that is evident in this study. Similarly, saturation was reached in dialogue with all providers that participated and they included participants from different backgrounds and roles, but it is unclear whether this would translate to be representative of all providers in each role. For example, though we had specialized law enforcement representation in the study, this might not translate to all specialized law enforcement professionals. It is also not possible to determine our response rate because recruitment was multi-faceted and largely community based. Overall, the limitations are overshadowed by the benefit of these findings for future study and practice implications.

Conclusion

Domestic violence has major impacts on survivors’ overall health and without intervention has the potential to persist over the life course. Thus, it is imperative to assess the impact that DV programs have on the survivors they serve. We still have very few studies that use the appreciative inquiry approach to understand what success generally means from the perspective of the survivor and service providers who work with these survivors. The findings from this study, therefore, provide a new perspective on success. This can be utilized to create measures for program outcomes that align with the definition of these factors of success. These findings open a fertile field for future research in creating evidence-based measures that can help to improve program outcomes for survivors of DV.

Grant Numbers and/or Funding Information

This research received financial support from the Center for Family Safety and Healing at Nationwide Children’s Hospital.

References

Beeble, M. L., Bybee, D., Sullivan, C. M., & Adams, A. E. (2009). Main, mediating, and moderating effects of social support on the well-being of survivors of intimate partner violence across 2 years. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(4), 718–729. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016140

Cattaneo, L. B., & Goodman, L. A. (2015). What is empowerment anyway? A model for domestic violence practice, research, and evaluation. Psychology of Violence, 5(1), 84–94. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035137.

Cooperrider, D. L., & Suresh, S. (1987). Appreciative inquiry in organizational life. Research in Organizational Change and Development, 1, 129–169.

DePrince, A. N. & Gagnon, K. L. (2018). Understanding the consequences of sexual assault: What does it mean for prevention to be trauma informed?. In Orchowski, L.M., & Gidycz, C.A. (Eds.), Sexual assault risk reduction and resistance (pp. 15–35). Academic Press.

Emerson, R., Fretz, R., & Shaw, L. (1995). Writing ethnographic fieldnotes. University of Chicago Press.

Flicker, S. M., Cerulli, C., Swogger, M. T., & Talbot, N. L. (2012). Depressive and posttraumatic symptoms among women seeking protection orders against intimate partners: Relations to coping strategies and perceived responses to abuse disclosure. Violence Against Women, 18(4), 420–436. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801212448897.

Fugate, M., Landis, L., Riordan, K., Naureckas, S., & Engel, B. (2005). Barriers to domestic violence help seeking: Implications for intervention. Violence Against Women, 77, 290–310.

Goodman, L., & Epstein, D. (2005). Refocusing on women: A new direction for policy and research on intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20(4), 479–487. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260504267838.

Goodman, L.A., Bennett Cattaneo, L.B., Thomas, K., Woulfe, J., Chong, S.K., & Smyth, K.F. (2014). Advancing domestic violence program evaluation: Development and validation of the Measure of Victim Empowerment Related to Safety (MOVERS). Psychology of Violence. http://dx.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038318.

Goodman, L. A., Thomas, K., Cattaneo, L. B., Heimel, D., Woulfe, J., & Chong, S. K. (2016). Survivor defined practice in domestic violence work: Measure development and preliminary evidence of link to empowerment. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 31(1), 163–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260514555131.

Goodman, L. A., Epstein, D., & Sullivan, C. M. (2017). Beyond the RCT: Integrating rigor and relevance to evaluate the outcomes of domestic violence programs. American Journal of Evaluation, 39(1), 58–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214017721008.

Hausman, A. J., Baker, C. N., Komaroff, E., Thomas, N., Geurra, T., Hohl, B. C., & Leff, S. S. (2013). Developing measures of community-relevant outcomes for violence prevention programs: A community-based participatory research approach to measurement. American Journal of Community Psychology, 52(3–4), 249–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-013-9590-6.

Kulkarni, S., Herman-Smith, R., & Ross, T. C. (2015). Measuring intimate partner violence (IPV) service providers’ attitudes: The development of the survivor-defined advocacy scale (SDAS). Journal of Family Violence, 30(7), 911–921. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-015-9719-5.

Leech, N. L., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2008). Qualitative data analysis: A compendium of techniques and a framework for selection for school psychology research and beyond. School Psychology Quarterly, 23(4), 587–604. https://doi.org/10.1037/1045-3830.23.4.587.

Liang, B., Goodman, L., Tummala-Narra, P., & Weintraub, S. (2005). A theoretical framework for understanding help-seeking processes among survivors of intimate partner violence. American Journal of Community Psychology, 36(1–2), 71–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-005-6233-6.

Lipsky, S., Field, C. A., Caetano, R., & Larkin, G. L. (2005). Posttraumatic stress disorder symptomatology and comorbid depressive symptoms among abused women referred from emergency department care. Violence and Victims, 20(6), 645–659. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.20.6.645.

Lyon, E., Bradshaw, J., & Menard, A. (2012). Meeting survivors’ needs through non-residential domestic violence services & supports: Results of a multi-state study. National Institute of Justice. https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/237328.pdf.

Melbin, A., Jordan, A., & Smith, K. F. (2014). How do survivors define success? A new project to address an overlooked question. The Full Frame Initiative. https://blueshieldcafoundation.org/sites/default/files/covers/How_Do_Survivors_Define_Success_FFI_Oct_2014_0.pdf.

Saleebey, D. (2006). The strengths perspective in social work practice. Pearson/Allyn & Bacon.

Sullivan, C.M. (2005). Interventions to address intimate partner violence: The current state of the field. In J.R. Lutzker (Ed.), Preventing violence: Research and evidence-based intervention strategies (pp. 195–212). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Sullivan, C. M. (2006). Mission-focused management and survivor-centered services: A survival guide for executive directors of domestic violence victim service agencies. Pennsylvania Coalition Against Domestic Violence.

Sullivan, C. M. (2011). Evaluating domestic violence support service programs: Waste of time, necessary evil, or opportunity for growth? Aggression and Violent Behavior, 16(4), 354–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2011.04.008.

Sullivan, C.M. (2012, updated January 2016). Examining the work of domestic violence programs within a “social and emotional well-being promotion” conceptual framework. National Resource Center on Domestic Violence. www.dvevidenceproject.org.

Vaughn, M. G., Salas-Wright, C. P., Cooper-Sadlo, S., Maynard, B. R., & Larson, M. (2015). Are immigrants more likely than native-born Americans to perpetrate intimate partner violence? Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 30(11), 1888–1904. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260514549053.

Westmarland, N., Kelly, L., & Chalder-Mills, J. (2010). Domestic violence perpetrator programmes: What counts as success? London Metropolitan University and Durham University. http://eprints.soton.ac.uk/id/eprint/369591.

Whittemore, R., Chase, S.K., & Mandle, C.L. (2001). Validity in qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, 11(4), 522–537. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973201129119299.

Woods, S. J. (2005). Intimate partner violence and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in women: What we know and need to know. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20(4), 394–402. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260504267882.

Zweig, J. M., & Burt, M. R. (2007). Predicting women’s perceptions of domestic violence and sexual assault agency helpfulness: What matters to program clients? Violence Against Women, 13(11), 1149–1178. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801207307799.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mengo, C., Casassa, K., Wolf, K.G. et al. Defining success for survivors of domestic violence: Perspectives from survivors and service providers. J Fam Viol 38, 463–476 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-022-00394-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-022-00394-6