Abstract

Mothers who experience intimate partner violence (IPV) are at increased risk for experiencing workplace instability in the form of absence from paid employment and job loss. In a cross-sectional study, we investigate if experiences of IPV inhibit work stability among low-income women as well as if the receipt of child care subsidies has a moderating effect on the relationship. Using data from the Illinois Families Study, we tested the relationships between IPV, work outcomes, and recipient of child care subsidies in a series of multivariate regressions. Findings indicate IPV is associated with reduced hours worked among low-income mothers and increased unemployment among low-income mothers. However, both of these relationships are moderated by receipt of child care subsidies suggesting that mothers who experience IPV can maintain employment at the same level as women not experiencing IPV with receipt of child care subsidies. Our findings indicate the importance of receiving child care subsidies among low-income mothers and support subsidy accessibility to survivors of IPV. Results of our study are limited in regard to the age of the data, the cross-sectional use of the data, and the lack of a control group that was not receiving any type of government assistance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Women who are survivors of intimate partner violence (IPV) face a multitude of employment barriers. The experience of violence hinders a woman’s ability to work directly when partners hide car keys or call excessively during work hours, and indirectly through the psychological consequences of abuse (Swanberg et al. 2006). Women who are subject to physical, psychological, and/or economic abuse by their romantic partner (hereafter referred to as survivors) face additional challenges as mothers, due to the high cost of child care and the economic consequences of leaving an abusive partner. The current study investigated how experiences of IPV impact work among low-income mothers and how financial assistance for child care can help mothers maintain employment.

IPV, Workplace Disruptions, and Work Instability

Workplace disruptions are tactics used by abusers before, after, and during work hours to prevent survivors from performing to the best of their ability. In one of the earliest known studies of survivor employment instability, approximately two thirds of participants reported experiencing workplace disruptions (Shepard and Pence 1988). However, researchers more recently have found much higher rates, reporting that 85% of survivors experience workplace disruptions (Logan et al. 2007; Swanberg et al. 2006).

Directly, abusers disrupt work through excessive calling or emailing, sabotaging childcare, threatening coworkers, and stalking. Receiving unwanted phone calls is thought to be the most common workplace disruption tactic with one study reporting that 62% of survivors repeatedly received unwanted phone calls in a 12-month period (Swanberg et al. 2006). In Logan and colleagues (Logan et al. 2007) mixed methods study, a survivor working at a hospital recalled, “I was so embarrassed, but he just keeps calling me back, at an emergency room where you can’t have the phone off the hook” (p.279). If calling does not capture survivors’ attention, abusive partners may resort to stalking. In a study of survivors seeking protection against abusers, survivors stalked at work reported being unable to perform at their job significantly more often than those who were not stalked (Logan et al. 2007). Stalking might lead to missing work because of its association with extreme forms of IPV like homicide or attempted homicide (McFarlane et al. 2002; Logan et al. 2007). Indirect workplace disruptions include abusive behavior before or after work that hinders survivors’ mental state in terms of concentration and performance while working. For instance, in Lloyd (1997) one participant recounts, “Around that time, when it [abuse] was on my mind, I did have problems …concentrating, and I was depressed about it, you’re just violated in such a way.” In a longitudinal study of survivor employment instability measuring multiple forms of emotional distress, the relationship between emotional distress and employment instability was statistically significant for those women who were survivors (Lindhorst et al. 2007). Therefore, indirect workplace disruptions that disrupt survivors’ concentration and performance may be comparable to direct disruptions.

As a result of the workplace disruptions caused by abusers, IPV survivors are likely to experience work instability. While the exact prevalence of work instability is unknown, Swanberg and colleagues (Swanberg et al. 2006) found that 71% of recently employed survivors seeking a domestic violence order (i.e., protection order against a male intimate partner) experienced at least one form of adverse work outcomes. Likewise, annually in the United States, 1 in 4 large private employers report incidents of IPV in the workplace or incidents in which an abuser, without relationship to the workplace, threatens or assaults the intended victim at the workplace (U.S. Department of Labor and Bureau of Labor Statistics 2006). Given the high prevalence of survivors’ employment instability, the current study examines the effect of IPV on two work outcomes: hours worked and employment status.

IPV and Employment Status

Although findings are mixed, there is some evidence that survivors are likely to experience job loss or unemployment as a result of abuse. In early research, 24% of survivors reported experiencing job loss (Shepard and Pence 1988). However, in a nationally representative study of women who had experienced interpersonal crimes, unemployment at baseline was not associated with a history of IPV (Bryne et al. 1999). Tolman and Rosen (2001) also did not find a significant relationship between unemployment and IPV ever or in the past year in a sample of women receiving government aid.

Qualitative research reveals a multitude of reasons that survivors resign or are terminated. First, it may be the workplaces do not have security to protect survivors, as one survivor recalls, “I had to resign from my job….My shift ended at 10:00 at night. There’s no way I was going to walk through the parking lot at 10:00 at night. No way” (Moe and Bell 2004, p.46). In addition, consistent absence from work could be grounds for termination. One survivor notes while hiding from her abuser, “I didn’t show up for three days…I called in finally and they said do not bother [coming back]” (Swanberg and Logan 2005, p.10).

It may be that the effects of IPV on employment status are most apparent when observed over time because of the gradual escalation of abuse. In a 10-year longitudinal study of mothers receiving welfare, exposure to IPV had a direct effect on employment status (Lindhorst et al. 2007). In this, survivors may be more likely to experience unemployment over the span of several months rather than at one selected time when compared to women who do not experience IPV (Adams et al. 2012).

IPV and Hours Worked

Previous research indicates that absence from work is likely the most common form of work instability that survivors experience. In one review of the literature, 11 of 20 studies of survivors’ work outcomes in the U.S. found survivors working fewer hours, days, weeks, and months out of the year as a result of their abuse (Showalter 2016). Tolman and Wang (2005) concluded that survivors miss 137 h of work annually or work 10% fewer hours than women who have not experienced IPV. Browne and colleagues (Browne et al. 1999) also showed that women who experienced IPV were significantly unlikely to maintain work for 30 h per week during the 6-month period following their initial interview than women who did not experience IPV. When work hours are lost by survivors’ health benefits, chance of promotion and coworker support may be jeopardized.

Loss of work hours may be associated with experiences of poverty for survivors. Smith (2001) found survivors earned $3900 less annually than women who did not experience IPV. Further, Adams et al. (2012) found that 54% of survivors experienced material hardships. According to nationally representative data, women with annual household incomes below $25,000 are more likely to experience IPV than women with higher incomes (Black et al. 2011). Taken together, these findings suggest that those who have lower means to deal with loss of income because of their vulnerable economic status are more likely to experience IPV and the associated financial burdens.

Child Care Subsidy, Work Outcomes, and IPV

Survivors who have children may face additional challenges in their workplaces because of the high cost of child care and the economic consequences of leaving an abusive partner. Studies have found that adverse work outcomes are significantly more likely to occur among mothers who experience IPV than mothers who do not experience IPV (Crowne et al. 2011; Riger et al. 2004; Tolman and Wang 2005). For instance, mothers face a unique work barrier when they need to protect their children as illustrated by a survivor who says, “…My baby comes first, you know. I could not leave my child home alone with him [abuser].. . I finally quit” (Swanberg and Logan 2005, p.10). Federal child care subsidies, which were designed to support maternal engagement in employment (Healy and Dunifon 2014), may play a protective role and buffer the negative influence of IPV on work outcomes by providing access to a safe place for their child as well as additional financial resources for child care.

The current subsidy program stems from the passage of welfare reform and was implemented to reduce child care cost related to employment. The high cost of child care may prohibit parents from securing employment as they are forced to stay home to care for their children in order to avoid care expenses. A number of studies have found that child care subsidies are associated with a greater likelihood of working (Bainbridge et al. 2003; Blau and Tekin 2007; Brooks et al. 2002; Crawford 2006; Tekin 2007). Additionally, receipt of child care subsidies is associated with an increased likelihood of working standard hours (8 am–6 pm; Tekin 2007) and a greater ability to meet employer demands related to working additional hours (Press et al. 2006).

In the general population research, child care subsidies have been found to decrease work disruptions, including experiencing a change in schedule, working fewer hours than desired, being unable to work overtime (Press et al. 2006), and being absent from work (Weinraub et al. 2005). One study found that receipt of subsidies was associated with a lower likelihood of having to miss work because child care fell through (Forry and Hofferth 2011). Because stable child care is a challenge for many low-income women, receipt of a subsidy likely reduces the overall work disruptions low-income women face.

Child care subsidies may be particularly helpful to mothers who are experiencing IPV. First, to the extent that survivors miss work because they fear leaving the child home alone with the abuser (Swanberg and Logan 2005), access to child care subsidies would provide access to a safe place for mothers to leave their child while they are working.

Second, after leaving an abusive partner, many women experience economic strain because of the loss of additional economic resources from their partner (Anderson et al. 2003; Riger et al. 2002). In one study, 67% of survivors with children who had recently accessed IPV services reported having child care needs (Allen et al. 2004). Because child care is very costly, this economic strain can make it difficult for mothers to leave abusive partners who are helping to contribute to child care costs and, in turn, making child care assistance a valuable resource (Anderson et al. 2003; Dichter and Rhodes 2011; Riger et al. 2002). In a national study of survivors receiving IPV services, participants who were receiving government assistance, including child care subsidies, were significantly more likely to feel economically empowered than non-recipients (Hetling and Postmus 2014). Further, survivors in multiple studies have identified a need for child care assistance (Eisenman et al. 2009; Dichter and Rhodes 2011). In fact, in one study of women who were experiencing IPV, subsidized child care was the number one most helpful tangible service survivors received in the aftermath of violence (Postmus et al. 2009).

Despite these possible pathways for the buffering impact of child care subsidies, no known study has specifically examined the impact of child care subsidies on the relationship between IPV and our selected work outcomes.

The Current Study

The current cross-sectional study addressed the following research questions: (1) In a sample of low-income mothers, is IPV associated with work status? (2) In a sample of low-income mothers, is IPV associated with work hours? (3) Does receipt of a child care subsidy moderate the relationship between IPV and work outcomes for these mothers? We hypothesize that IPV will increase the unemployment of mothers who are experiencing IPV and that IPV will reduce the number of hours that mothers work. Further, we hypothesize that the relationship between IPV and both work outcomes will be buffered by receipt of child care subsidies.

The current study built on previous research of child care subsidy receipt and mothers’ employment. While studies have established that IPV does decrease work stability (Browne et al. 1999; Meisel et al. 2003; Tolman and Wang 2005; Swanberg et al. 2006), a review of the research has yielded no known studies that explore the relations between IPV, receipt of child care subsidies, and work outcomes. Further, given the mixed results on the effect of IPV on work status (Shepard and Pence 1988; Bryne et al. 1999; Tolman and Rosen 2001), the current study adds to existing research by exploring work status among low-income mothers who met inclusion criteria. Based on previous research (Press et al. 2006; Postmus et al. 2009), there is reason to believe that receipt of child care subsidies will improve work outcomes for mothers experiencing IPV but the current study is innovative in exploring child care subsidies’ protective effect.

Methods

Source of Data

To explore the impact of receiving child care subsidies on IPV survivors’ experiences of employment, we utilized cross-sectional data from the Illinois Families Study (IFS) The IFS data utilizes stratified sampling of 1899 TANF recipients in 1998 residing in urban and rural areas (Joo Lee et al. 2004). The stratified sampling design led to overrepresentation of TANF recipients living in southern Illinois and so researchers constructed base weights to correct for this overrepresentation. In addition, nonresponse weights were constructed using sampling frame data from administrative records that account for the greatest amount of variation in response probabilities (Holl et al. 2005; Joo Lee et al. 2004; Institute for Social Research 1992).

In addition, the IFS data were linked to the child care subsidy administrative data from the Illinois Department of Human Services (IDHS.. Among selected sample (N = 1899), the current study focused on the 72% of participants who responded to wave one of IFS from November 1999 to September 2000 (N = 1362), agreed to link their survey into administrative data (N = 1260), and mothers who had children who were 12 years or younger (N = 1100). The IFS is ideal for this analysis given that IFS contains work outcomes, IPV items, and administrative record of child care subsidy receipt. Using Little’s (1988) MCAR test, we tested the missing patterns and found that they were missing completely at random. In addition, given the low missing rate (less than 0.5% of some variables), probably due to the benefits of face-to-face interviewing, we used complete data on all study variables (N = 1087). Despite having relatively low missingness in the data, it should be noted that the group of 1087 mothers that comprise our sample likely differ from the full sample of mothers that were identified for the overall study. Specifically, only mothers who responded to the first wave of IFS and to have their administrative data linked were included. Mothers who did not agree to participate or to have their data linked likely differed from mothers who agreed in important ways. Additionally, due to the age of the data and the evolution of welfare policy since the time of collection, our cross-sectional use of the data, as well as the lack of a control group in which participants were not receiving any type of government assistance, the current study has limitations that must be considered when interpreting the findings and their generalizability.

Measures

Dependent Variables

Two variables were used to measure employment. First, work status was measured by a binary variable from “Are you currently working for pay?” for which responses are coded as (1) for yes and (0) for no. Second, number of working hours was measured as a continuous variable from “Including overtime, how many hours did you work last week for all of your employers combined?” Although these items are only asked at one point in time from wave 1 survey, related cross-sectional studies (i.e., Lloyd and Taluc 1999; Swanberg et al. 2006) have similarly conceptualized workplace outcomes.

Independent Variable

Experiences of IPV among mothers served as an independent variable in this study. Mothers were asked about their experiences of IPV based on three items of physical abuse, which were adapted from the Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus 1979) and from the Massachusetts study of women on welfare (Allard et al. 1997). If participants responded that their partner had hit, slapped, or kicked them; thrown or shoved them to the floor; and/or hurt them badly enough for them to go to the doctor in the past 12 months they were considered to be experiencing IPV. IPV was measured as a dichotomized variable in which responses are coded as (1) if a mother reported experience with any of these violent actions in the past 12 months and (0) reported none of these violent actions in the past 12 months.

Moderator

Mother’s IFS survey data was matched to the Illinois Department of Human Services (IDHS)‘s Child Care Subsidy administrative data. At the time of the survey, families were eligible for child care subsidy if their household income was below 50% of the state median income ($1818.00 per month for a family of three) or 157% of the federal poverty level (Lewis et al. 2000). Although the IFS draws from caseloads of TANF recipients, not all participants in the study were receiving TANF and thus are not all subject to the same requirements to receive subsidy. If receiving TANF, parents did not have to be working to receive child care subsidy but they had to participate in a work related activity. For families not receiving TANF but meeting household income guidelines, subsidy eligibility criteria were considered met if they were involved in one of the following activities: working, obtaining a college degree and working part-time, or accessing English as a Second Language program, vocational training, or a high school degree equivalent program. The duration for all families to be eligible for child care subsidy receipt was two years.

Child care subsidy receipt was measured using monthly receipt data of child care subsidy. It was measured as a dichotomized variable indicating (1) if a mother received at least one-month child care subsidy in the past 12 months before the survey and (0) if a mother did not receive any child care subsidy in the past 12 months before the survey.

Covariates

We controlled for a number of factors related to IPV and workplace outcomes (Hart and Klein 2013; Swanberg et al. 2006) and factors controlled for in the survivors’ employment instability literature (i.e., Adams et al. 2012; Bryne et al. 1999). Using baseline survey data, maternal race and ethnicity were coded as Black (non-Hispanic), white (non-Hispanic), and Hispanic or other race. Maternal education was dichotomously coded to indicate whether the mother had less than a high school education or more. Marital status was dichotomously coded to indicate if the mother was married versus not married. Similarly, participants were coded as having a mental health problem if they answered yes to the question “In the past 12 months have you ever felt that you needed treatment for a mental health problem?” Age and number of children were treated as continuous variables.

Analytic Strategy

We used STATA 15 for all cross-sectional analysis in this study. Independent t-tests for continuous variables and chi square tests for categorical variables were used to compare the group differences between mothers who received child care subsidies and mothers who did not receive child care subsidies. Multivariate logistic regression was used to explore the effect of IPV on work status that was measured as a binary variable while controlling other variables. Multivariate OLS regression was used to explore the effect of IPV on the number of working hours (which was measured as a continuous variable) while controlling other variables. To see the main effect of IPV and the moderating effects of receiving child care subsidies on work outcomes, we used hierarchical multiple regression: a IPV variable was included in the first model along with other confounding variables, a child care subsidy receipt variable was include in the second model, and an interaction term of child care subsidy receipt and IPV was included in the final model. As previously mentioned, statistical weights were used in all analyses to adjust for the overrepresentation of small counties and survey non-response.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive statistics of the sample can be found in Table 1. The majority of participants identified as non-Hispanic African American (79.1%) with a small portion identifying as Hispanic or other race (13.3%) and non-Hispanic White (7.6%) The average age of participants was 30 years of age (SD = 7.14) and the average number of children that mothers had was 2 children (SD = 1.25). Most mothers were unmarried (80%), and about 40% of the sample attained less than a high school education. Approximately 7% of the sample was experienced a mental health problem that they felt warranted treatment in the past 12 months and approximately 5% had experienced at least one form of IPV. In terms of workplace stability, about half of the sample (50.5%) were employed and the average working hours in the last week were 16 h (SD = 18.6). Compared to mothers who did not receive child care subsidies mothers who received subsidies were more likely to have a high school degree, more children, were employed with longer working hours, less likely to have mental health problems, and less likely to experience physical IPV.

Multivariate Regression Results

IPV, Child Care Subsidy, and Work Status

The findings from the regression models are located in Table 2. Model 1 (M1) showed the main effect of IPV on work status, Model 2 (M2) adds the main effect of receiving a child care subsidy, and Model 3 (M3) adds the interaction effect between the two. In M1, we found that there was no main effect of IPV on work status. Adding in receiving a child care subsidy (M2), we found that subsidy receipt was associated with an increased likelihood that the mother was working: mothers who received a child care subsidy were 2.69 times more likely to be working compared to mothers who did not receive a child care subsidy. Finally, after including the interaction effect between IPV and receiving a child care subsidy (M3), we found the interaction was statistically significant. The relationship between child care subsidy receipt and work status was stronger for mothers experiencing IPV compared to those who were not experiencing IPV. As illustrated in Fig. 1, among mothers receiving a child care subsidy (red line), IPV had almost no impact on work status while among those mothers not receiving a child care subsidy (blue line), IPV had a significant detrimental effect on work status.

In terms of control variables, we found that being older and being Hispanic—compared to Black—were associated with greater odds of working. There were no significant differences between White and Black mothers. Having less than a high school degree, having mental health concerns, and having more children were associated with lower odds of working.

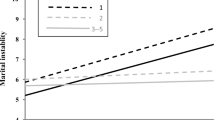

IPV, Child Care Subsidy, and Hours Worked

Models 4–6 repeat the pattern of models above, but instead examine hours worked per week rather than the dichotomous measure of whether the mother worked or not. In our model of the main effect of IPV on work hours (M4) we found that physical abuse was associated with reduced hours worked, by approximately 5.4 h in the last week. In our model of the main effect of child care subsidy receipt on work hours (M5), we found that subsidy receipt was associated with increased hours worked by approximately 8.23 h in the last week. Last, we found that there is a moderation effect of child care subsidy receipt on the relationship between IPV and work hours (M6). Specifically, the relationship between child care subsidy receipt and hours worked was stronger for mothers experiencing IPV; that is, child care subsidy had a stronger positive effect on hours worked among mothers experiencing IPV compared to mothers who were not experiencing IPV. As seen in Fig. 2, among mothers receiving child care subsidy (red line), IPV had very little impact on the number of hours worked, while IPV had a strong negative effect on hours worked for those mothers who were not receiving subsidy (blue line).

We find in M6 that being Hispanic compared to being Black, married (compared to being unmarried), and older age were associated with an increase in work hours. However, having less than a high school degree, the presence of mental health concerns, and having more children were associated with working fewer hours.

Discussion

In our cross-sectional examination of the effect of IPV on work outcomes in a sample of mothers who agreed to have their administrative benefits data linked to their survey data, we found that IPV is associated with decreased number of hours worked but not work status. Additionally, child care subsidy receipt was associated with greater odds of working and increased number of hours worked. Finally, child care subsidy receipt had a protective effect for mothers experiencing IPV; that is, child care subsidy receipt buffered the relationship between IPV and work. Keeping in mind the age of our data, findings might not reflect the current experience of working and receiving welfare. In addition, the cross-sectional design does not allow for us to look at the effect of receiving subsidy over time and working nor does our lack of control group allow us to compare receiving subsidy to not receiving any government assistance. The findings that receipt of child care subsidy was related to work outcomes may be confounded by work requirements of receiving subsidy. Specifically, in order to receive and continue receiving child care subsidies, parents must be working or participating in work-related activities (e.g. searching for a job, completing job training).

Consistent with related literature, we did not find a main effect of IPV on work status but did find a main effect of IPV on work hours (Tolman and Rosen 2001; Browne et al. 1999). In Browne and colleagues’ (Browne et al. 1999) study of homeless and extremely poor families, researchers found that only when work was defined specifically in terms of hours and months did the effect of IPV emerge. Thus, it may be that IPV has a similar effect with the mothers in the current sample experiencing IPV who do not suffer from unemployment but instead struggle to maintain work hours due to abuser-initiated workplace disruptions (i.e., excessive calling or emailing, sabotaging childcare, threatening coworkers, and stalking at the workplace). It may also be that many of the mothers in the current sample are receiving welfare and thus required to meet welfare work requirements, confounding the relationship between IPV and work status.

Our finding that child care subsidy receipt is associated with both work outcomes provides support for subsidy programs and policies. Our finding that child care subsidy receipt is associated with increased work hours is consistent with previous literature (Bainbridge et al. 2003; Blau and Tekin 2007; Brooks et al. 2002; Crawford 2006; Tekin 2007). Receiving subsidy allows mothers to decide if they will seek employment because they are no longer obligated to stay home to care for their children in order to avoid the high cost of child care. Further, our finding that child care subsidy receipt has an effect on hours worked is also supported by previous literature (Tekin 2007; Press et al. 2006). If mothers are able to obtain child care through subsidy receipt, they can increase their working hours thereby increasing income for themselves and their children, a particularly important phenomenon for mothers experiencing IPV. It is also important to note that there are work requirements for receiving child care subsidies. Therefore, in addition to the positive benefits of having access to child care, the mothers may be more likely to work by virtue of the work requirements of receiving subsidy.

The interaction effect between subsidy receipt and IPV is in line with findings that child care subsidies are a great need among IPV survivors (Postmus et al. 2009). When low-income mothers experiencing IPV have access to child care by way of child care subsidies, they are void of the burden of finding day-to-day care and can attend work, focusing on the financial stability for themselves and their children. In other words, if child care support provides a buffer for complex stressors like IPV, child care subsidies provide a critical tool for this high-risk group of mothers.

Limitations

Although the current study contributes to existing knowledge of working mothers and survivors of IPV, the study does have limitations. First, we relied on a sample of mothers who had participated in the first wave of IFS data collection and agreed to have their administrative data linked to their survey data. It is possible that mothers who did not participate in the first wave or refused to have their administrative data linked differed from our sample of mothers in important ways. Second, as is common in studies examining IPV, there was a relatively low incidence rate of IPV in our sample, hindering our statistical power. As a result, the findings may be dominated by the larger sample of mothers who are not experiencing IPV. Third, in the current study we only consider items of physical abuse but in reality survivors of IPV experience abuse from their partners in a variety of ways, all of which should be considered in future work. Emotional abuse likely effects both work outcomes in the current study and future research would be wise to focus on mothers who suffer from mental health problems who may be less likely to concentrate at work. Fourth, our study is also limited to reports of hours worked in the past week. Measurement of hours worked over several weeks or months would give a more reliable estimate of the time mothers’ spend on-the-job in a typical week and may capture greater hour instability given the complexity and chronicity of IPV. Fifth, because our employment data asks about current employment and IPV was reported on for the past twelve months, there is a potential lag between IPV experience and work outcomes. Because this is a frequent problem in this literature, future research should seek to align the timescales of questions or, more desirably, to examine each of these constructs at multiple time points. It is also true that the sample can only be generalized to other low-income mothers who receive welfare. This may be of concern given that IPV impacts women of all socioeconomic statuses (Hart and Klein 2013) and thus it is unclear how child care assistance might affect mothers whose finances are controlled by their partners but who are not receiving welfare benefits. Sixth, the age of the data is a limitation considering changes in subsidy policy, welfare-to-work standards, and advances in knowledge regarding the effect of IPV on employment since the time of IFS data collection. Finally, because child care subsidies require work or work-related activities, the relationship demonstrated between subsidy receipt and improved work outcomes may be driven by the requirements of receiving the subsidy. However, programs requiring work do not always have success in improving work among participants. Studies of the Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) program, which has similar work requirements, have shown that stable employment among recipients is not the norm, and that improvements in employment among TANF recipients were modest and faded over time (Pavetti 2018).

Future work should test key mechanisms that may underlie our findings but that we were unable to directly test. Specifically, future work should examine whether receipt of child care subsidies was in fact associated with lower levels of stress among mothers experiencing IPV and whether subsidy receipt was associated with fewer workplace disruptions. A focus on these mechanisms will provide key information on both how subsidies matter in the lives of women experiencing IPV but also will be useful to the design of other interventions focused on improving workplace outcomes for this population.

Conclusion

Despite these limitations, the current study has several important implications. Findings from this study support the distribution of child care subsidy to low income mothers, particularly those who are experiencing IPV. In addition to being an effective work support for mothers experiencing child care problems and IPV, child care subsidies may be an important factor in supporting survivors’ ability to leave abusive relationships given the prior findings from Postmus and colleagues (Postmus et al. 2009) that help with child care was critical to survivors’ success after leaving their abusive partner. Programs assisting survivors should help connect survivors to public benefits, including child care subsidies, in order to support them and increase their likelihood of success. Additionally, policymakers should consider additional resources to child care centers to improve the quality and reliability of care for low-income families. By decreasing the likelihood that child care arrangements will fall through and enhancing flexibility to meet the schedules of low-income working survivors, child care subsidies can positively influence women’s work outcomes.

References

Adams, A. E., Tolman, R. M., Byee, D., Sullivan, C. M., & Kennedy, A. C. (2012). The impact of intimate partner violence on low-income women’s economic well-being: The mediating role of job stability. Violence Against Women, 18(12), 1345–1367. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801212474294.

Allard, M., Albelda, R., Colten, M., & Cosenza, C. (1997). In harm’s way? Domestic violence, AFDC receipt, and welfare reform in Massachusetts. Boston, MA: University of Massachusetts at Boston.

Allen, N., Bybee, D., & Sullivan, C. (2004). Battered Women's Multitude of Needs. Violence Against Women, 10(9), 1015–1033.

Anderson, M. A., Gillig, P. M., Sitaker, M., McCloskey, K., Malloy, K., & Grigsby, N. (2003). “Why doesn't she just leave?”: A descriptive study of victim-reported impediments to her safety. Journal of Family Violence, 18, 151–155.

Bainbridge, J., Meyers, M., & Waldfogel, J. (2003). Child care policy reform and the employment of single mothers. Social Science Quarterly, 84(4), 771–791. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0038-4941.2003.08404002.x.

Black, M. C., Basile, K. C., Breiding, M. J., Smith, S. G., Walters, M. L., Merrick, M. T., Chen, J., & Stevens, M. R. (2011). The national intimate partner and sexual violence survey (NISVS): 2010 summary report. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Blau, D. M., & Tekin, E. (2007). The determinants and consequences of child care subsidies for single mothers in the USA. Journal of Population Economics, 20, 719–741. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-005-0022-2.

Brooks, F., Risler, E., Hamilton, C., & Nackerud, L. (2002). Impacts of child care subsidies on family and child well-being. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 17(4), 498–511.

Browne, A., Salomon, A., & Bassuk, S. S. (1999). The impact of recent partner violence on poor women’s capacity to maintain work. Violence Against Women, 5(4), 393–426. https://doi.org/10.1177/10778019922181284.

Bryne, C. A., Resnick, H. S., Kilpatrick, D. G. Best, C. L., & Saunders, B. E. (1999). Thesocioeconomic impact of interpersonal violence on women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67 (3), 362–366.

Crawford, A. (2006). The impact of child care subsidies on single mothers' work effort. Review of Policy Research, 23, 699–711. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-1338.2006.00224.x.

Crowne, S. S., Juon, H., Ensminger, M., Burrell, L., McFarlane, E., & Duggan, A. (2011). Concurrent and long-term impact of intimate partner violence on employment stability. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(6), 1282–1304. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260510368160.

Dichter, M. E., & Rhodes, K. V. (2011). Intimate partner violence survivor’s unmet social service needs. Journal of Social Service Research, 37(5), 481–489.

Eisenman, D. P., Richardson, E., Sumner, L. A., Ahmed, S. R., Liu, H., Valentine, J., & Rodriguez, M. A. (2009). Intimate partner violence and community service needs among pregnant and post-partum Latina women. Violence and Victims, 24, 111–121.

Forry, N., & Hofferth, S. (2011). Maintaining work: The influence of child care subsidies on child care–related work disruptions. Journal of Family Issues, 32(3), 346–368. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X10384467.

Hart, J. D., & Klein, A. (2013). Practical implications of current intimate partner violence research for victim advocates and service providers. Retrieved from https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/244348.pdf

Healy, O., & Dunifon, R. (2014). Child-care subsidies and family well-being. Social Service Review, 88, 493–528. https://doi.org/10.1086/677741.

Hetling, A., & Postmus, J. (2014). Financial literacy and economic empowerment of survivors of intimate partner violence: Examining the differences between public assistance recipients and nonrecipients. Journal of Poverty, 18(2), 130–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/10875549.2014.896308.

Holl, J. L., Slack, K. S., & Stevens, A. B. (2005). Welfare reform and health insurance: Consequences for parents. American Journal of Public Health, 95(2), 279–285. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2003.025882.

Institute for Social Research. (1992). Panel study of income dynamics: Procedures and tape codes, 1992 interviewing year. Ann Arbor, Mich: Institute for Social Research.

Joo Lee, B., Slack, K. S., & Lewis, D. A. (2004). Are welfare sanctions working as intended? Welfare receipt, work activity, and material hardship among TANF-recipient families. Social Service Review, 78(3), 370–403. https://doi.org/10.1086/421918.

Lewis, D. A., Shook, K. L., Stevens, A. B., Kleppner, P., Lewis, J., & Riger, S. (2000). Work, welfare and well-being: An independent look at welfare reform in Illinois. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University.

Lindhorst, T., Oxford, M., & Gillmore-Rogers, M. (2007). Longitudinal effects of domestic violence on employment and welfare outcomes. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 22(7), 812–828.

Little, R. J. (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83(404), 1198–1202.

Logan, T. K., Shannon, L., Cole, J., Swanberg, J. (2007). Partner stalking and implications for women's employment. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 22(3), 268–291.

Lloyd, S. (1997). The effects of domestic violence on women’s employment. Law & Policy, 19(2), 139–167.

Lloyd, S., & Taluc, N. (1999). The effects of male violence on female employment. Violence Against Women, 5(4), 370–392. https://doi.org/10.1177/10778019922181275.

McFarlane, J., Campbell, J., & Watson, K. (2002). Intimate partner stalking and femicide: Urgent implications for women's safety. Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 20, 51–68.

Meisel, J., Chandler, D., & Rienzi, B. (2003). Domestic violence prevalence and effects on employment in two California TANF populations. Violence Against Women, 9(10), 1191–1212. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801203255861.

Moe, A. M., & Bell, M. P. (2004). Abject economics: The effects of battering and violence on women’s work and employability. Violence Against Women, 10(1), 29–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801203256016.

Pavetti, L. (2018). Evidence Doesn’t Support Claims of Success of TANF Work Requirements. Center on budget and policy priorities. DC: Washington.

Postmus, J., Severson, M., Berry, M., & Yoo, J. A. (2009). Women’s experiences of violence and seeking help. Violence Against Women, 15(7), 852–868. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801209334445.

Press, J., Fagan, J., & Laughlin, L. (2006). Taking pressure off families: Child-care subsidies lessen mothers’ work-hour problems. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 155–171. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00240.x.

Riger, S., Raja, S., & Camacho, J. (2002). The radiating impact of intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 17, 184–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260502017002005.

Riger, S., Staggs, S. L., & Schewe, P. (2004). Intimate partner violence as an obstacle to employment among mothers affected by welfare reform. Journal of Social Issues, 60(4), 801–818. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-4537.2004.00387.x.

Shepard, M., & Pence, E. (1988). The effect of battering on the employment status of women. Affilia, 3(2), 55–61.

Showalter, K. (2016). Women’s employment and domestic violence: A review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 31, 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2016.06.017.

Smith, M. W. (2001). Abuse and work among poor women: Evidence from Washington State. Research in Labor Economics, 20, 67–102.

Straus, M. (1979). Measuring Intrafamily conflict and violence: The conflict tactics (CT) scales. Journal of Marriage and Family, 41(1), 75–88. https://doi.org/10.2307/351733.

Swanberg, J. E., & Logan, T. K. (2005). Domestic violence and employment: A qualitative study. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 10(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.10.1.3.

Swanberg, J. E., Macke, C., & Logan, T. K. (2006). Intimate partner violence, women, and work: Coping on the job. Violence and Victims, 21(6), 561–578. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.21.5.561.

Tekin, E. (2007). Single mothers working at night: Standard work and child care subsidies. Economic Inquiry, 45(2), 233–250.

Tolman, R. M., & Rosen, D. (2001). Domestic violence in the lives of women receiving welfare: Mental health, substance dependence, and economic well-being. Violence Against Women, 7(2), 141–158.

Tolman, R. M., & Wang, H. (2005). Domestic violence and women’s employment: Fixed effects models of three waves of women’s employment study data. American Journal of Community Psychology, 36, 147–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801201007002003.

U.S. Department of Labor, & Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2006). Survey of Workplace Violence Prevention, 2005. D.C.: Washington.

Weinraub, M., Shlay, A. B., Harmon, M., & Tran, H. (2005). Subsidizing child care: How child care subsidies affect the child care used by low-income black families. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 20, 373–392.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the Secondary Analysis of Data on Early Care and Education, Grant Number 90YE0173, from the Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, the Administration for Children and Families, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The project described was supported by award numbers R25HD074544, P2CHD058486, and 5R01HD036916 awarded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development or the National Institutes of Health.

Administrative data linkages were developed by the Chapin Hall Center for Children, and survey data were collected by the Metro Chicago Inforamtion Center (MCIC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Showalter, K., Maguire-Jack, K., Yang, MY. et al. Work Outcomes for Mothers Experiencing Intimate Partner Violence: the Buffering Effect of Child Care Subsidy. J Fam Viol 34, 299–308 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-018-0009-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-018-0009-x