Abstract

There is a significant association between childhood abuse and suicidal behavior in low-income African American women with a recent suicide attempt. Increasingly, empirical focus is shifting toward including suicide resilience, which mitigates against suicidal behavior. This cross-sectional study examines childhood abuse, intrapersonal strengths, and suicide resilience in 121 African American women, average age of 36.07 years (SD = 11.03) with recent exposure to intimate partner violence and a suicide attempt. To address the hypothesis that childhood abuse will be negatively related to suicide resilience and that this effect will be mediated by intrapersonal strengths that serve as protective factors, structural equation modeling examined the relations among three latent variables: childhood abuse (measured via physical, sexual, and emotional abuse), intrapersonal strengths (assessed by self-efficacy and spiritual well-being), and suicide resilience (operationalized via the three components of suicide resilience—internal protective, external protective, and emotional stability). The initial measurement model and the structural model both indicated excellent fit. Results indicated that childhood abuse was negatively associated with intrapersonal strengths and suicide resilience, intrapersonal strengths were positively associated with suicide resilience, and intrapersonal strengths fully mediated the association between childhood abuse and suicide resilience. Thus, the results suggest a positive and protective influence of intrapersonal strengths on suicide resilience in the face of childhood abuse in suicidal African American women. The clinical implications and directions for future research that emerge from these findings are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Childhood adversities are robust predictors of suicidal behavior (Borges et al. 2010). These experiences (maltreatment/abuse, loss, family and household dysfunction, physical illness) results in a two to five fold increase for the risk of attempted suicide (Dube et al. 2001). The greater the number of adversities endorsed, the greater the risk for suicidal behavior (Dube et al. 2001; Enns et al. 2006). Childhood abuse is the adversity that presents the greatest risk for developing suicidal ideation and attempts (Enns et al. 2006). When other childhood adversities are controlled for, there remains a link between childhood abuse and later suicidal behavior (Molnar et al. 2001). Although prior research has examined the links between childhood abuse and both suicidal ideation and attempts, only recently (Allbaugh et al. 2017) has empirical attention has been given to the association between childhood abuse and suicidal resilience, that is the capacity to cope with suicidal thoughts without attempting suicide due to the availability of support and resources. Thus, this study focuses on suicide resilience in African American women who experienced the most relevant form of childhood adversity, namely childhood abuse.

Childhood abuse, which can be physical, emotional, and/or sexual in nature, is a major social problem that affects countless youth and families and results in large societal costs (Jud et al. 2016; Wildeman et al. 2014). It is reported at unusually high rates among African Americans (Wildeman et al. 2014). While this may reflect racially-biased reporting, poverty is a primary reason African American youth experience higher rates of abuse and more negative sequelae than youth from other ethno-racial groups (Lanier et al. 2014). Childhood abuse is associated with adverse psychological consequences in adulthood, including mood, anxiety, trauma and stressor-related, and substance use disorders (Carr et al. 2013; Lindert et al. 2014), as well as problems with intrapersonal functioning (Godbout et al. 2014). These associations have been replicated in African American samples (Cross et al. 2015).

Childhood abuse is a risk factor for suicidal behavior in diverse groups (Anda et al. 2006; Briere et al. 2016; Devries et al. 2014; Dube et al. 2001; Fuller-Thomson et al. 2012; Harford et al. 2014), including low-income African American women (Anderson et al. 2002). Suicidal behavior, a major cause of disease burden and death, emerges in response to biological, psychological, and social factors (Curtin et al. 2016a). Historically, African American women have demonstrated low risk for death by suicide due to supportive networks, strong religious ties and spiritual beliefs, a communal orientation, and cultural beliefs about the unacceptability of taking one’s life (Utsey et al. 2007b). However, a 2016 report revealed that suicide rates for non-Hispanic black women have increased in the past fifteen years (Curtin et al. 2016a, b) and African American women have a higher lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts than African American men (Joe et al. 2006). Although attention has been paid to suicidal behavior in African American women, only recently has suicide resilience been studied in this population (Allbaugh et al. 2017).

Given the increasing suicide rates among African American women, attention must be paid to the affective, behavioral, and cognitive processes and environmental support factors that enable them to effectively deal with suicidal thoughts and attempts (Osman et al. 2004; Rutter et al. 2008). These processes and supports in persons who are suicidal can be conceptualized as suicide resilience – the perceived internal and external capacity, resources, and competence to modulate suicidal ideation, emotions, and attitudes (Johnson et al. 2011; Osman et al. 2004). Distinct from suicide risk, suicide resilience is more than the absence of suicidal thoughts and behaviors. It is a constellation of factors that protect an individual from engaging in suicidal behavior in response to major stressors, other risk factors, and suicidal thoughts (Johnson et al. 2011; Osman et al. 2004). As suicide this constellation of factors serves to modulate suicidality. Suicide resilience distinguishes between suicidal and non-suicidal individuals and has been linked to higher levels of reasons for living and lower levels of psychological distress such as anxiety, depression, and hopelessness (Guitierrez et al. 2012; Moody and Smith 2013; Osman et al. 2004; Rutter et al. 2008). It falls within the rubric of resilience more broadly, namely the intrapersonal, social/situational, and cultural/environmental conditions associated with the capacity to adapt in response to stress and adversity (Masten 2014). While suicide resilience can be understood as an intervening (i.e., mediator, moderator) variable if the outcome is suicidal behavior (e.g., ideation, attempts), when examined in individuals who have attempted suicide, as in the current study, it may be conceptualized as an outcome variable. There already is precedent for viewing suicide resilience as an outcome variable in individuals who have attempted suicide (Allbaugh et al. 2017).

A wealth of literature underscores the importance of researching protective factors that may explain the trajectories of resilience individuals demonstrate in response to stress and adversity, as these variables can serve as key targets for prevention and intervention efforts (Sabina and Banyard 2015; Zimmerman et al. 2013). However, only recently have resilience trajectories been studied among individuals who have attempted suicide. One recent study found that perceived burdensomeness and acquired capacity for suicide, but not thwarted belongingness, mediated the links between childhood abuse and suicide resilience in low-income African American female suicide attempters (Allbaugh et al. 2017). Self-efficacy and spiritual well-being are two potential intrapersonal strengths that may serve a mediating function vis-à-vis suicide resilience for low-income African American females with a recent suicide attempt who were abused as children. Both self-efficacy and spiritual well-being are intrapersonal strengths as they protect African American women against suicidal behavior (Kaslow et al. 2002). Although distinctly different constructs, together they predict hope and quality of life (Adegbola 2011; Duggleby et al. 2009), which are theoretically related to suicide resilience (Mosqueiro et al. 2015; Rutter et al. 2008). Thus, they are personal resources that while potentially related to the suicide resilience construct, are distinct from the construct.

Self-efficacy (judgments or perceptions about ability to perform tasks related to attaining a performance goal and cope with stressors) has been encouraged in African American women (Woods-Giscombé 2010). It has been found to differentiate between African American women who have attempted suicide and those who have never attempted suicide, as well as to protect them against suicidal behavior (Kaslow et al. 2002; Meadows et al. 2005; Thompson et al. 2002). Among African American, but not White, female adolescents, lowered self-efficacy has been associated with suicidal ideation, plans, and attempts (Valois et al. 2015). Thus, self-efficacy may be a culturally-relevant intrapersonal protective factor for low-income, African American women with a childhood abuse history (Afifi and MacMillan 2011).

Spiritual well-being (strength drawn from one’s sense of purpose and connectedness to a higher power) is another culturally-relevant intrapersonal protective factor for African American women who are more likely than non-Hispanic Whites to endorse high levels of spirituality and subjective religiosity (Chatters et al. 2008). It encompasses religious (sense of comfort derived from connectedness to a higher power that is sacred and eternal) and existential (subjective sense that one’s life has meaning, purpose, and value, regardless of religious elements) well-being. It contributes to enhanced physical health, mood, and self-esteem, and reduced traumatic stress (Utsey et al. 2007a), including in African American female trauma survivors (Stevens-Watkins et al. 2014).

These findings highlight the value of identifying factors that protect against deleterious outcomes and bolster suicide resilience in individuals who have attempted suicide. Consistent with this, the overall aim of this study was to determine if intrapersonal strengths serve a protective function in the childhood abuse-suicide resilience link in low-income African American women with a recent suicide attempt. For statistical reasons (Kline 2016), we examined this question using latent constructs and thus the first hypothesis pertained to these constructs. We hypothesized that physical, emotional, and sexual abuse would be associated with childhood abuse; self-efficacy and spiritual well-being would be associated with intrapersonal strengths; and the three components of suicide resilience would be associated with suicide resilience. Second, in preparation for the mediational question, we postulated that childhood abuse would be negatively related with intrapersonal strengths and suicide resilience and intrapersonal strengths would be positively related to suicide resilience. Finally, in keeping with the study’s overall aim, we hypothesized that intrapersonal strengths would partially mediate the childhood abuse-suicide resilience link.

Method

Participants

Data were collected from 121 self-identified low-income African American women, ages 18–57 (M = 36.07, SD = 11.03) who reported a suicide attempt and exposure to intimate partner violence in the prior year or currently. It is important to note that intimate partner violence was experienced by all the participants and as such was not a variable examined in the present study. These cross-sectional data are drawn from the pre-intervention assessments associated with a randomized controlled trial for abused, suicidal African American women (Kaslow et al. 2010; Taha et al. 2015). Approximately 42% of the participants reported being single/never married, 82.1% were unemployed, 43.4% had not completed high school, and approximately 60% did not have health insurance in any form. Additional descriptive information regarding the sample is included in Table 1.

Procedure

After approval by the university’s and hospital’s institutional review boards, this study took place in a leading public academic healthcare system in the southeastern United States that provides care to underserved community members residing in local counties. Women entered via referral or recruitment from the medical or psychiatric emergency rooms or clinics throughout this healthcare system. Potential participants were screened by a research team member. Screening questions focused on the inclusion criterion related to demographics (aged 18–64, self-identification as African American) and both intimate partner violence and a suicide attempt in the previous 12 months. Level of suicidal intent was determined via the Suicide Intent Scale (Beck et al. 1974), which has good predictive validity (Steffansson et al. 2012) and is associated with reasons for living in low-income African American women who have attempted suicide (Flowers et al. 2014). Women were disqualified if they had a life-threatening medical condition, significant cognitive impairment, and/or were acutely psychotic. Those who did not meet study criteria were given appropriate hospital and community resources.

Women who met inclusion criterion were assessed within the week. Due to low levels of health literacy of patients in the healthcare system, a team member verbally administered these 2–3 h assessments in a private space. Assessments included 29 measures, five of which are included in this study. As compensation for their time, women received $20 and the equivalent of roundtrip fare on the city transit system to cover transportation costs. Referrals were made for women who endorsed being imminently suicidal or homicidal or who were acutely psychotic.

Measurement of Constructs

Demographics

Devised for use in this and previous studies, the Demographic Data Questionnaire (Kaslow et al. 2010) includes questions related to demographic factors including but not limited to age, employment status, insurance access, living situation, and educational level.

Childhood Abuse

Childhood abuse was assessed via the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire – Short Form (CTQ-SF) (Bernstein et al. 2003). The physical, emotional, and sexual abuse subscales served as the observed variables that combined were used as indicators on the latent construct, childhood abuse (described below). A commonly used measure, the CTQ-SF has 25 clinical and three validity items. A 5-point Likert scale is used, which ranges from Never True (1) to Very Often True (5). There is strong support for the internal consistency reliability of the subscales and the re-test reliability and criterion validity of the measure. Factor analyses demonstrate structural invariance across diverse samples (Bernstein et al. 2003; Spinhoven et al. 2014), which suggests good construct validity. With regard to using the CTQ-SF in those with childhood abuse histories, convergent validity with clinical interviews has been demonstrated (Etain et al. 2013), as has strong test–retest reliability suggesting that retrospective reports using this measure are reliable over time (Shannon et al. 2016). The coefficient alphas for the subscales have been reported to range from 0.71 to 0.93 (Bernstein and Fink 1998). In this study, the internal consistency reliability for childhood abuse was 0.92.

Intrapersonal Strengths

The latent construct, intrapersonal strengths, was comprised of two observed variables, self-efficacy as well as spiritual well-being. Self-efficacy was measured by the 12-item Self-Efficacy Scale for Battered Women (SESBW) (Varvaro and Palmer 1993) that taps engagement in adaptive help-seeking behaviors and adaptive living skills. Items were ranked from 0 (couldn’t do it at all) to 100 (completely sure I could do it) and summed to get a rating of self-efficacy. In other samples of women who have experienced abuse, including African American women, the measure has demonstrated good internal consistency reliability (Meadows et al. 2005; Thompson et al. 2002; Varvaro and Palmer 1993) (α= 0.88 in the current sample). The scale also has shown to have good construct validity in other samples (Varvaro and Palmer 1993), including abused and suicidal African American women (Kaslow et al. 2002). Spiritual well-being was assessed with the Spiritual Well-Being Scale (SWBS) (Paloutzian and Ellison 1991), a two factor self-report measure that focuses on religious and existential well-being. There are 20 items rated on a 6-point Likert scale (strongly agree to strongly disagree), with higher scores indicating greater levels of well-being. Considerable psychometric data support the reliability and validity of this measure. The scale has demonstrated good internal consistency and test–retest reliability in multiple samples (Fernander et al. 2004; Genia 2001; Paloutzian and Ellison 1991). Based on sophisticated factor analyses with large samples, the two factor model remains most appropriate to utilize (Murray et al. 2015). The measure has good psychometric properties with African Americans including internal consistency reliability (α= 0.83 in the current study) and concurrent and predictive validity (Arnette et al. 2007).

Suicide Resilience

The latent construct of suicide resilience was assessed via the three subscales of the Suicide Resilience Inventory (SRI-25) (Osman et al. 2004), which measures factors that mitigate against suicidal ideation and intent. Items are scored on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree); higher scores indicate greater protection against suicidal thoughts and behaviors. This scale encompasses three subscales: internal protective (positive views of self and life satisfaction), external protective (capacity to seek out helpful external supports in the face of personal challenges or suicidal ideation), and emotional stability (positive views of one’s ability to modulate suicide-related ideation and actions in response to distressing feelings and events). Confirmatory factor analyses with U.S. and international samples have confirmed these three dimensions (Fang et al. 2014; Rutter et al. 2008). The measure has good to excellent internal consistency reliability (α= 0.93 for the total score in the current study) and adequate to good construct, concurrent, and discriminant validity across adolescent and adult samples and among African American samples (Fang et al. 2014; Guitierrez et al. 2012; Osman et al. 2004; Rutter et al. 2008).

Data Analytic Plan

To describe the sample, descriptive statistics were calculated with SPSS 23. To understand the relations between the observed variables and latent constructs, both a measurement model and a structural model were conducted utilizing structural equation modeling (SEM) with Mplus7 (Muthen and Muthen 2012). A multivariate statistical analytic approach that converges multivariate regression and factor analysis, SEM is useful for measuring the relations among observed and latent constructs along with theory testing and has the advantage of examining overall model fit (Kline 2016). More specifically, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) assessed the measurement model fit in relation to the associations between the observed indicators and latent variables. Latent regression was performed to ascertain the structural model which refers to the relations among the latent variables, namely the links among the independent (childhood abuse), mediator (latent construct of intrapersonal strengths that includes self-efficacy and spiritual well-being), and outcome (suicide resilience) latent variables. Because multiple indicators are recommended for latent variables (Kenny and McCoach 2003), emotional abuse, physical abuse, and sexual abuse were used as separate indicators of the latent variable, childhood abuse. The self-efficacy scale along with the spiritual well-being scale made up the latent variable, intrapersonal strengths. The items on the Suicide Resilience Inventory-25 (Internal Protective, External Protective, and Emotional Stability) were utilized as the three indicator variables to constitute the latent variable, suicide resilience. Analyzing latent variables has the advantage of reducing measurement error and was thus utilized in the model.

We examined multiple fit indices to determine if both the measurement and the structural models adequately fit the data: Chi square statistic (χ2) Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker- Lewis Index (TLI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) (Zhonglin et al. 2004). A χ 2, which must be reported for SEM, reflects the difference between the observed and estimated relations based on the specified model; a nonsignificant χ 2 demonstrates good model fit (Kline 2016). The commonly reported CFI, which is less affected by sample size than is the χ 2, assumes that all latent variables are uncorrelated, and compares the sample covariance matrix with the null model. The TLI, also called the Non-Normed Fit Index, is an incremental fit index that resolves some of the negative bias associated with the normed fit index. The RMSEA, one of the most instructive and parsimonious fit indices, provides information about how well the model matches the population’s covariance matrix. The value of 0.90 is recommended for the CFI, and 0.95 is suggested for the TLI. RMSEA values of less than 0.07 reflect adequate to good model fit.

Finally, a mediation analysis was performed with Mplus7. We used the maximum likelihood method (ML) estimation and bootstrapped 3,000 samples (MacKinnon 2008). The bootstrapping approach is highly recommended to address unmet assumptions about the data (e.g., normality) (Preacher and Hayes 2008). To test our hypotheses about the relations among the latent variables, namely that childhood abuse would be negatively associated with intrapersonal strengths, intrapersonal strengths would be positively related to suicide resilience, childhood abuse would be negatively related to suicide resilience, and intrapersonal strengths would mediate the link between childhood abuse and suicide resilience, the following paths were examined: (a) direct effect of childhood abuse on intrapersonal strengths; (b) direct effect of intrapersonal resilience on suicide resilience; (c) direct effect of the childhood abuse on suicide resilience, controlling for intrapersonal strengths; (d) indirect effect (mediating) of childhood abuse on suicide resilience through intrapersonal strengths. The analyses were conducted utilizing latent variables to reduce measurement error and avoid multicollinearity challenges that may emerge in regression analyses (Kline 2016). Missing data were analyzed utilizing the Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) estimation.

Results

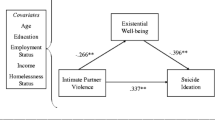

Measurement models map measures onto theoretical constructs. In this model, emotional, physical, and sexual abuse; self-efficacy and spiritual well-being; and three aspects of suicide resilience were considered observed variables, whereas childhood abuse, intrapersonal strengths, and suicide resilience were treated as latent variables (Table 2). As hypothesized, the χ 2 statistic was nonsignificant (χ 2 = 24.58, df = 17, p = .11); the observed model and estimated relations in the specified model were not different. Fit indices indicated an excellent model fit: (CFI = 0.98; TLI = 0.96; RMSEA = 0.06). See Fig. 1. Thus, the measures of the three types of childhood abuse, self-efficacy and spiritual well-being, and the three aspects of suicide resilience adequately mapped onto the proposed theoretical constructs of childhood abuse, intrapersonal strengths, and suicide resilience respectively.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (Standardized Estimates). C 2 = 24.58, df = 17, p = .01; CFI = 0.98; TLI = 0.96; RMSEA = 0.06; N = 121. *: p < .05; **: p < .001. ctqab: childhood emotional abuse; ctqpab: childhood physical abuse; ctqsab: childhood sexual abuse; swbs: Spiritual well-being; sesbw: Self-efficacy in black women; sriint: suicide resilience internal protective factors; sriext: suicide resilience external protective factors; sriemo: suicide resilience emotional resources

Given that this measurement model demonstrated an excellent fit, we moved forward with the structural model to examine the associations among the theoretical variables. Similar to the measurement model, we expected the three latent constructs to demonstrate adequate to excellent model fit. As hypothesized, the model χ 2 = 24.58, df = 17, p = .11) and the fit indices suggested an excellent fit (CFI = 0.98; TLI = 0.96; RMSEA = 0.06).

The examination of the relations among the latent variables revealed that, as expected, childhood abuse was negatively associated with intrapersonal strengths, intrapersonal strengths was positively associated with suicide resilience, and childhood abuse was negatively associated with suicide resilience. An examination of the hypothesis that intrapersonal strengths would mediate the link between childhood abuse and suicide resilience showed that the model fit remained excellent (χ 2 = 24.58, df = 17, p = .11, CFI = 0.98. TLI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.06). See Fig. 2. As expected, the indirect effect of childhood abuse on suicide resilience through intrapersonal strengths was significant, (ab = − 0.34, SE = 0.11, 95% CI = − 0.5, -0.14) where a = − 0.38, SE = 3.83, 95% CI = − 0.64, − 0.17 and b = 0.89, SE = 0.83, 95% CI = 1.25, 7.03). Notably, results revealed complete mediation; the path between childhood abuse and suicide resilience was reduced to zero and was no longer significant in the presence of the mediator variable (c’ = − 0.13, SE = 0.11, 95% CI = − 0.32, 0.04). Thus, results support a complete mediation (See Fig. 2).

Mediation Model. C 2* = 24.58, df = 17, p = .30, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.06 where ab* (indirect effect) = − 0.34, SE = 0.11, 95% CI = -0.50, -0.14; a* = − 0.38, SE = 3.83, 95% CI = − 0.64, − 0.17; b = 0.89, SE = 0.83, 95% CI = − 0.32, 0.04; c’* = − 0.13, SE = 0.11, 95% CI = − 0.32, − 0.04. *: p < .05; **: p < .001

Discussion

This research represents one of the earliest efforts to examine suicide resilience in African Americans. It is critical to study this construct in this racial group, as culture impacts the extent and nature of the endorsement of suicidal thoughts and behaviors (Fang et al. 2014). As the authors discussed, suicide resilience is influenced by one’s culture. The internal and external resources tapped at such vulnerable phases of life are significantly dependent on specific cultural norms. Moreover, the results advance our understanding of suicide resilience in a high-risk group of African American women in three key ways. They provide evidence that childhood abuse negatively impacts intrapersonal strengths and suicide resilience; intrapersonal strengths manifested in self-efficacy and spiritual well-being serve a protective function as reflected in their association with suicide resilience; and the effect of childhood abuse on suicide resilience is mediated by intrapersonal strengths.

The data are consistent with study hypotheses and highlight the negative and enduring impacts of childhood abuse. They indicate that childhood abuse is associated with lower levels of intrapersonal strengths and a reduced capacity for suicide resilience in adulthood. The resilience science literature demonstrates that perceived efficacy and control, religion, spirituality, positive religious coping, and a belief that life has meaning are key correlates of resilience in the face of biopsychosocial risk factors and adversity (Brewer-Smyth and Koenig 2014; Bryant-Davis and Wong 2013). In addition, one other recent study found an association between childhood abuse and suicide resilience in African American women (Allbaugh et al. 2017). Although there is limited research on the childhood abuse – self-efficacy link, our findings are in keeping with social cognitive theory and positive psychology (Harris and Thoresen 2006) and evidence from other investigations that childhood abuse is associated with lowered self-efficacy (Soffer et al. 2008). The correlation that emerged between childhood abuse and spiritual well-being is consistent with findings that adult survivors of childhood abuse who endorse positive forms of spiritual coping exhibit lower levels of psychological distress and those who use negative forms of spiritual coping show the opposite pattern (Gall 2006).

The results gleaned from this study also emphasize the positive and protective influence that self-efficacy and spiritual well-being play in fostering suicide resilience and in mediating the link between childhood abuse and suicide resilience in the study population. These data build upon prior research showing links between both self-efficacy beliefs and physical and behavioral health-related outcomes in individuals exposed to collective trauma (Luszczynska et al. 2009) and between levels of spiritual well-being and suicidal behavior in multiple populations (Taliaferro et al. 2009), including in the African American community (Gaskin-Wasson et al. 2016; Meadows et al. 2005).

Limitations

The study findings must be considered in the context of several methodological limitations. The first relates to the sample, which was clinical in nature and restricted to one gender, social class, racial/ethnic, and geographic group. While the high-risk burden and relative homogeneity of the sample can be considered study strengths in relation to culturally-relevant research, the findings may have limited generalizability to other sociodemographic groups. Another concern about the sample is that the participants endorsed intimate partner violence experiences in the prior year. This potentially limits the findings to African American women without such a history, especially given the high rates of co-occurrence of childhood abuse and intimate partner violence (Widom et al. 2014) and intimate partner violence and suicide attempts (Devries et al. 2013). Despite concerns about the sample, the results are relevant to a group of at-risk, minority, and underserved individuals. The second limitation pertains to the cross-sectional design, which means that causality cannot be discerned and thus the associations found are correlational in nature. In other words, the concurrent assessment of predictor, mediator, and outcome variables is a limitation. The third limitation relates to measurement issues. There are challenges with adults’ recall of childhood abuse and thus the assessment of this construct is fraught with bias (Baker 2009). Additionally, retrospective accounts of childhood maltreatment in adulthood often fail to capture trauma that had been prospectively documented in childhood (Shaffer et al. 2008; Widom et al. 2004). As another example, while the measure of spiritual well-being functioned as expected, future efforts may be strengthened by including a revised or new measure of this construct better suited to nonreligious as well as religious individuals and that has less item covariance related to item wording and complexity (Murray et al. 2015). In addition, the measure of suicide resilience appears to include one subscale that pertains to suicide vulnerability (emotional stability) and two subscales that address supports and resources more generally (internal protective, external protective). Moreover, the internal protective scale on the SRI may be related to intrapersonal strengths generally and thus there may be overlap between the intrapersonal strengths and suicide resilience constructs. Further, the measure may not tap elements of resilience central to African American culture. A fourth limitation is that childhood abuse was the only negative life event of focus. There are numerous other childhood adversities associated with suicide attempts (Borges et al. 2010), all of which should be explored in the future. A fifth limitation is that there may be some overlap in the intrapersonal resources and suicide resilience constructs. Finally, while there are statistical and conceptual advantages to using latent rather than observed constructs in SEM, the fact that two of the latent variables are composed of subscales of single measures, the finding of a good fit between the observed and latent constructs may be statistically significant but not practically relevant.

Clinical Implications

Despite the study’s limitations, several clinical implications emerge from the findings. Given that many individuals do not access healthcare when they experience suicidal distress and that African Americans are less likely than their Caucasian counterparts to receive specialty behavioral health services or any healthcare services in response to suicidal behavior (Ahmedani et al. 2015), more systematic and culturally-relevant outreach and stigma reduction efforts are required in the African American community (Hatzenbuehler et al. 2013). For African American women with a history of childhood abuse and suicidal behavior who do seek services, interventions that incorporate positive psychology’s emphasis on self-efficacy may be beneficial (Harris and Thoresen 2006). Preliminary data with adolescents demonstrate that a self-efficacy based preventive intervention that teaches the detection of warning signs for suicidality and appropriate help-seeking activities is associated with reduced hopelessness, sadness, and suicidality and increased self-efficacy and behavioral intentions related to help-seeking (King et al. 2011). A positive psychology approach that integrates forgiveness training may be particularly effective with childhood abuse survivors (Harris and Thoresen 2006). Forgiveness therapy entails exploring the pain and anger related to the trauma; committing to forgiving the perpetrator by giving up resentment and responding with good will; gaining insight and understanding about the perpetrator, and ultimately working toward resolution of the pain and meaning and purpose in the forgiveness process (Enright and Fitzgibbons 2015). It supports individuals in reclaiming their compassion toward self and others, without minimizing the injustice of the trauma. Forgiveness therapy has positive outcomes with survivors of childhood abuse (Freedman and Enright 1996). To ensure that such positive psychology interventions with the target population are culturally-informed, they must respect the women’s faith traditions, beliefs, and values and incorporate these in their efforts to facilitate trauma recovery (Bryant-Davis and Wong 2013). For example, they can bolster religious and spiritual forms of coping, such as spiritual meaning-making, as these are associated with enhanced survivor resilience and better psychological outcomes (Glenn 2014). Faith-based community resources can be capitalized upon for their provision of social support and promotion of forgiveness, both of which can optimize stress resilience and neurobiological, physical, and behavioral health outcomes (Brewer-Smyth and Koenig 2014; Bryant-Davis and Wong 2013).

Directions for Future Research

There are a number of future research directions that deserve consideration. First, given that the study was conducted with a specific sociodemographic and vulnerable population, the model should be tested with other populations to determine its relevance and generalizability. Second, as noted earlier, childhood abuse is a risk factor for suicidal behavior in adults (Devries et al. 2014; Harford et al. 2014; Norman et al. 2012), including among African American women (Kaslow et al. 2002). There is a significant and graded association between adverse childhood experiences, such as childhood abuse, and risk of attempted suicide for multiple populations, including African American women (Anderson et al. 2002). Moreover, the type of childhood abuse impacts one’s risk for future suicide attempts (Power et al. 2016). It be may be valuable in the future to inspect the link between the presence, nature, and number of types of childhood adversities and suicide resilience in African American women, as well as in other sociodemographic groups of individuals. Third, to develop a more comprehensive picture of the ways in which self-efficacy and spiritual well-being lead to suicide resilience, future research should investigate motivational processes, in addition to self-efficacy, and incorporate constructs relevant to spiritual well-being, such as religiosity, spiritual coping, and specific spiritual beliefs and practices (Gall 2006; Mahoney 2010). Fourth and in a related vein, although intrapersonal strengths mediated the childhood abuse – suicide resilience link, it would be prudent to examine additional mediating constructs. Potential intrapersonal, social/situational, and cultural/environmental variables to include are other protective factors shown to positively impact adult outcome of survivors of childhood abuse, such as coping and social support (Sperry and Widom 2013; Walsh et al. 2010), and/or to ameliorate people’s risk for suicidal ideation and attempts, such as positive self-appraisal, optimism, reasons for living, hopefulness, meaning in life, religious involvement, adaptive coping skills, social support, and effectiveness in obtaining resources (Bakhiyi et al. 2016; Huffman et al. 2016; Johnson et al. 2010; Kaslow et al. 2005, 2002; Marco et al. 2016; Meadows et al. 2005; Utsey et al. 2007b). In addition, future research should examine key sociodemographic factors (e.g., unemployment, homelessness) as potential moderators of the various mediational links. Finally, although suicide resilience often is conceptualized as a mediating construct, in the current study based upon the model being examined and the sample being studied, it was used as the outcome variable. In future work, it would be interesting to re-examine the model with suicide resilience as the mediator and intrapersonal strengths as the outcome variables. Ideally, both models could be studied not only prospectively, but also longitudinally, to determine the optimal conceptualization of suicide resilience.

References

Adegbola, M. (2011). Spirituality, self-efficacy, and quality of life among adults with sickle cell disease. South Online Journal of Nursing Research, 11. Retrieved from http://www.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/ANAMarketplace/ANAPeriodicals/OJIN/TableofContents/Volume62001/No2May01/ArticlePreviousTopic/emSouthernOnlineJournalofNursingResearchemElectronicPublicationofResearch.aspx.

Afifi, T. O., & MacMillan, H. L. (2011). Resilience following child maltreatment: a review of protective factors. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 56, 266–272. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371105600505.

Ahmedani, B. K., Stewart, C., Simon, G. E., Lynch, F. L., Lu, C. Y., Waitzfelder, B. E., et al. (2015). Racial/ethnic differences in health care visits made before suicide attempt across the United States. Medical Care, 53, 430–435. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000335.

Allbaugh, L. J., Florez, I. A., Turmaud, D. R., Quyyum, N., Dunn, S. E., Kim, J., et al. (2017). Child abuse-suicide resilience link in African American women: interpersonal psychological mediators. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2017.1350773.

Anda, R. F., Felitti, V. J., Bremner, J. D., Walker, J. D., Whitfield, C. L., Perry, B. D., et al. (2006). The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood: a convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 256, 174–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4.

Anderson, P. L., Tiro, J. A., Price, A., Bender, M., & Kaslow, N. J. (2002). Additive impact of childhood emotional, physical, and sexual abuse on suicide attempts among low-income, African American women. Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior, 32, 131–138. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.32.2.131.24405.

Arnette, N. C., Mascaro, N., Santana, M. C., Davis, S., & Kaslow, N. J. (2007). Enhancing spiritual well-being among suicidal African American female survivors of intimate partner violence (IPV). Journal of Clinical Psychology, 63, 909–924. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20403.

Baker, A. J. L. (2009). Adult recall of childhood psychological maltreatment: definitional strategies and challenges. Children and Youth Services Review, 31, 703–714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.03.001.

Bakhiyi, C. L., Calati, R., Guillaume, S., & Courtet, P. (2016). Do reasons for living protect against suicidal thoughts and behaviors? A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 77, 92–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.02.019.

Beck, A. T., Schuyler, D., & Herman, I. (1974). The development of suicide intent scales. In A. T. Beck, H. L. Resnick & D. J. Littieri (Eds.), Prediction of suicide (pp. 45–56). Bowie: Charles Press.

Bernstein, D. P., & Fink, L. (1998). Childhood Trauma Questionnaire: A retrospective self-report. San Antonio: Harcourt, Brace, and Company.

Bernstein, D. P., Stein, J. A., Newcomb, M. D., Walker, E., Pogge, D., Ahluvalia, T., et al. (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse and Neglect, 27, 169–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0.

Borges, G., Nock, M. K., Abad, J. M. H., Hwang, I., Sampson, N. A., Alonso, J., et al. (2010). Twelve month prevalence of and risk factors for suicide attempters in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 71, 1617–1628. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.08m04967blu.

Brewer-Smyth, K., & Koenig, H. G. (2014). Could spirituality and religion promote stress resilience in survivors of childhood trauma. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 35, 251–256. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2013.873101.

Briere, J., Madni, L. A., & Godbout, N. (2016). Recent suicidality in the general population: multivariate association with childhood maltreatment and adult victimization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 31, 3063–3079. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260515584339.

Bryant-Davis, T., & Wong, E. C. (2013). Faith to move mountains: religious coping, spirituality, and interpersonal trauma recovery. American Psychologist, 68, 675–684. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034380.

Carr, C. P., Martins, C. M.-S., Stingel, A. M., Lemgruber, V. B., & Jurena, M. F. (2013). The role of early life stress in adult psychiatric disorders: a systematic review according to childhood trauma subtypes. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 201(12). https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000049.

Chatters, L. M., Taylor, R. J., Bullard, K. M., & Jackson, J. S. (2008). Spirituality and subjective religiosity among African Americans, Caribbean Blacks, and Non-Hispanic Whites. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 47, 725–737. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5906.2008.00437.x.

Cross, D., Crow, T., Powers, A., & Bradley, B. (2015). Childhood trauma, PTSD, and problematic alcohol and substance use in low-income, African-American men and women. Child Abuse & Neglect, 44, 26–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.01.007.

Curtin, S. C., Warner, M., & Hedegaard, H. (2016a). Increase in suicide in the United States, 1999–2014. NCHS data brief, no 241. Hyattsville: National Center for Health Statistics.

Curtin, S. C., Warner, M., & Hedegaard, H. (2016b). Suicide rates for females and males by race and ethnicity: United States, 1999 and 2014. NCHS Health E-Stat: National Center for Health Statistics.

Devries, K. M., Mak, J. Y., Bacchus, L. J., Child, J. C., Falder, G., Petzold, M., et al. (2013). Intimate partner violence and incident depressive symptoms and suicide attempts: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. PLoS Medicine, 10, e1001439. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001439.

Devries, K. M., Mak, J. Y. T., Child, J. C., Falder, G., Bacchus, L. J., Astbury, J., et al. (2014). Childhood sexual abuse and suicidal behavior: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 133, e1331-e1344. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-2166.

Dube, S. R., Anda, R. F., Felitti, V. J., Chapman, D. P., Williamson, D. F., & Giles, W. H. (2001). Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span: findings from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. Journal of the American Medical Association, 286, 3089–3096. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.286.24.3089.

Duggleby, W., Cooper, D., & Penz, K. (2009). Hope, self-efficacy, spiritual well-being and job satisfaction. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65, 2376–2385. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05094.x.

Enns, M. W., Cox, B. J., Afifi, T. O., De Graaf, R., Ten Have, M., & Sareen, J. (2006). Childhood adversities and risk for suicidal ideation and attempts: a longitudinal population-based study. Psychological Medicine, 36, 1769–1778. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291706008646.

Enright, R. D., & Fitzgibbons, R. P. (2015). Forgiveness therapy: An empirical guide for resolving anger and restoring hope. Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

Etain, B., Aas, M., Andreassen, O. A., Lorentzen, S., Dieset, I., Gard, S., et al. (2013). Childhood trauma is associated with severe clinical characteristics of bipolar disorders. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 74, 991–998. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.13m08353.

Fang, Q., Freedenthal, S., & Osman, A. (2014). Validation of the Suicide Resilience Inventory-25 with American and Chinese college students. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 45, 51–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12108.

Fernander, A., Wilson, J. F., Staton, M., & Leukefeld, C. (2004). An exploratory examination of the Spiritual Well-Being Scale among incarcertated Black and White male drug users. INternational Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 48, 403–413. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X04263450.

Flowers, K. C., Walker, R. L., Thompson, M. P., & Kaslow, N. J. (2014). Associations between reasons for living and diminished suicide intent among African-American female suicide attempters. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 202, 569–5757. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000170.

Freedman, S. R., & Enright, R. D. (1996). Forgiveness as an intervention goal with incest survivors. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64, 983–992. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.64.5.983.

Fuller-Thomson, F., Baker, T. M., & Brennenstuhl, S. (2012). Evidence supporting an independent association between childhood physical abuse and lifetime suicidal ideation. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 42, 279–291. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-278X.2012.00089.x.

Gall, T. L. (2006). Spirituality and coping with life stress among adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Child Abuse and Neglect, 30, 826–834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.01.003.

Gaskin-Wasson, A. L., Walker, K. L., Shin, L. J., & Kaslow, N. J. (2016). Spiritual well-being and psychological adjustment: mediated by interpersonal needs. Journal of Religion and Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-016-0275-y.

Genia, V. (2001). Evaluation of the Spiritual Well-Being Scale in a sample of college students. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 11, 25–33. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327582IJPR1101_03.

Glenn, C. T. B. (2014). A bridge over troubled waters: spirituality and resilience with emerging adult childhood trauma survivors. Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health, 16, 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/19349637.2014.864543.

Godbout, N., Briere, J., Sabourin, S., & Lussier, Y. (2014). Child sexual abuse and subsequent relational and personal functioning: the role of parental support. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38, 317–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.10.001.

Guitierrez, P. M., Freedenthal, S., Wong, J. L., Osman, A., & Norizuki, T. (2012). Validation of the Suicide Resilience Inventory-25 (SRI-25) in adolescent psychiatric inpatient samples. Journal of Personality Assessment, 94, 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2011.608755.

Harford, T. C., Yi, H.-Y., & Grant, B. F. (2014). Associations between childhood abuse and interpersonal aggression and suicide attempt among U.S. adults in a national study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38, 1389–1398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.02.011.

Harris, A. H. S., & Thoresen, C. E. (2006). Extending the influence of positive psychology interventions into health care settings: lessons from self-efficacy and forgiveness. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1, 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760500380930.

Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Phelan, J. C., & Link, B. G. (2013). Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. American Journal of Public Health, 103, 813–821. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.301069.

Huffman, J. C., Boehm, J. K., Beach, S. R., Beale, E. E., DuBois, C. M., & Healy, B. C. (2016). Relationship of optimism and suicidal ideation in three groups of patients at varying levels of suicide risk. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 77, 76–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.02.020.

Joe, S., Baser, R. E., Breeden, G., Neighbors, H. W., & Jackson, J. S. (2006). Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts among Blacks in the United States. Journal of the American Medical Association, 296, 2112–2123. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.296.17.2112.

Johnson, J., Gooding, P. A., Wood, A. M., & Tarrier, N. (2010). Resilience as positive coping appraisals: testing the schematic appraisals model of suicide (SAMS). Behavior Research and Therapy, 48, 179–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2009.10.007.

Johnson, J., Wood, A. M., Gooding, P., Taylor, P. J., & Tarrier, N. (2011). Resilience to suicidality: the buffering hypothesis. Clinical Psychology Review, 31, 563–591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.12.007.

Jud, A., Fegert, J. M., & Finkelhor, D. (2016). On the incidence and prevalence of child maltreatment: a research agenda. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 10, 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-016-0105-8.

Kaslow, N. J., Leiner, A. S., Reviere, S. L., Jackson, E., Bethea, K., Bhaju, J., et al. (2010). Suicidal, abused African American women’s response to a culturally-informed intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78, 449–458. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019692.

Kaslow, N. J., Sherry, A., Bethea, K., Wyckoff, S., Compton, M., Bender, M., et al. (2005). Social risk and protective factors for suicide attempts in low income African American men and women. Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior, 35, 400–412. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2005.35.4.400.

Kaslow, N. J., Thompson, M. P., Okun, A., Price, A., Young, S., Bender, M., et al. (2002). Risk and protective factors for suicidal behavior in abused African American women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70, 311–319. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.70.2.311.

Kenny, D. A., & McCoach, D. B. (2003). Effect of the number of variables on measures of fit in structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling, 10, 333–351. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM1003_1.

King, K. A., Strunk, C. M., & Sorter, M. T. (2011). Preliminary effectiveness of Surviving the Teens® Suicide Prevention and Depression Awareness Program on adolescents’ suicidality and self-efficacy in performing help-seeking behaviors. Journal of School Health, 81, 581–590. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00630.x.

Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th edition). New York: The Guilford Press.

Lanier, P., Maguire-Jack, K., Walsh, T., Drake, B., & Hubel, G. (2014). Race and ethnic differences in early chldhood maltreatment in the United States. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 35, 419–426. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000083.

Lindert, J., von Ehrenstein, O. S., GRashow, R., Gal, G., Braehler, E., & Weisskopf, M. G. (2014). Sexual and physical abuse in childhood is associated with depression and anxiety over the life course: systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Public Hleath, 59, 359–372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-013-0519-5.

Luszczynska, A., Benight, C. C., & Cieslak, R. (2009). Self-efficacy and health-related outcomes of collective trauma: a systematic review. European Psychologist, 14, 51–62. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040.14.1.51.

MacKinnon, D. P. (2008). Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Mahwah: Earlbaum.

Mahoney, A. (2010). Religion in families, 1999–2009: a relational spirituality framework. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 805–827. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00732.x.

Marco, J. H., Perez, S., & Garcia-Alandete, J. (2016). Meaning in life buffers the association between risk factors for suicide and hopelessness in participants with mental disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 72, 689–700. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22285.

Masten, A. S. (2014). Global perspectives on resilience in children and youth. Child Development, 85, 6–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12205.

Meadows, L. A., Kaslow, N. J., Thompson, M. P., & Jurkovic, G. J. (2005). Protective factors against suicide attempt risk among African American women experiencing intimate partner violence. American Journal of Community Psychology, 36, 109–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-005-6236-3.

Molnar, B. E., Berkman, L. F., & Buka, S. L. (2001). Psychopathology, childhood sexual abuse and other childhood adversities: relative links to subsequent suicidal behaviour in the US. Psychological Medicine, 31, 965–977. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291701004329.

Moody, C., & Smith, N. G. (2013). Suicide protective factors among trans adults. Archives of Sexual Behaviora, 43, 739–752. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-013-0099-8.

Mosqueiro, B. P., da Rocha, N. S., & de Almeida Fleck, M. P. (2015). Intrinsic religiosity, resilience, quality of life, and suicide risk in depressed inpatients. Journal of Affective Disorders, 179, 128–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.03.022.

Murray, A. L., Johnson, W. B., Gow, A. J., & Deary, I. J. (2015). Disentangling wording and substantive factors in the Spiritual Well-Being Scale. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 7, 120–129. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038001.

Muthen, L. K., & Muthen, B. O. (2012). MPLUS user guide (7th edition). Los Angeles: Muthen & Muthen.

Norman, R. E., Byambaa, M., De, R., Butchart, A., Scott, J., & Vos, T. (2012). The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Medicine, 9. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349.

Osman, A., Gutierrez, P. M., Muehlenkamp, J. J., Dix-Richardson, F., Barrios, F. X., & Kopper, B. A. (2004). Suicide Resilience Inventory – 25: development and preliminary psychometric properties. Psychological Reports, 94, 1349–1360. https://doi.org/10.2466/PRO94.3.1349-1360.

Paloutzian, R. E., & Ellison, C. W. (1991). Manual for the spiritual well-being scale. Navack: Life Advance.

Power, J., Gobeil, R., Beaudette, J. N., Ritchie, M. B., Brown, S. L., & Smith, H. P. (2016). Childhood abuse, nonsuicidal self-injury, and suicide attempts: an exploration of gender differences in incarcerated adults. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12263.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Contemporary approaches to assessing mediation in communication research. In A. F. .Hayes, M. D. Slater & L. B. Snyder (Eds.), The Sage sourcebook of advanced data analysis methods for communication research (pp. 13–54). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Rutter, P. A., Freedenthal, S., & Osman, A. (2008). Assessing protection from suicidal risk: psychometric properties of the Suicide Resilience Inventory. Death Studies, 32, 142–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180701801295.

Sabina, C., & Banyard, V. (2015). Moving toward well-being: the role of protective factors in violence research. Psychology of Violence, 4, 337–342. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039686.

Shaffer, A., Huston, L., & Egeland, B. (2008). Identification of child maltreatment using prospective and self-report methodologies: a comparison of maltreatement incidence and relation to later psychopathology. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32, 682–692. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.09.010.

Shannon, C., Hanna, D., Tumelty, L., Waldron, D., Maguire, C., Mowlds, W., et al. (2016). Reliability of reports of chldhood trauma in bipolar disorder: a test-retest study over 18 months. Journal of Trauma & Dissocation, 17, 511–519. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2016.1141147.

Soffer, N., Gilboa-Schechtman, E., & Shahar, G. (2008). The relationship of childhood emotional abuse and neglect to depressive vulnerability and low self-efficacy. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 1, 151–162. https://doi.org/10.1521/ijct.2008.1.2.151.

Sperry, D. M., & Widom, C. S. (2013). Child abuse and neglect, social support, and psychopathology in adulthood: a prospective investigation. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37, 415–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.02.006.

Spinhoven, P., Penninx, B. W., Hickendorff, M., van Hemert, A. M., Bernstein, D. P., & Elzinga, B. M. (2014). Childhood Trauma Questionnaire: factor structure, measurement invariance, and validity across emotional disorders. Psychological Assessment, 26, 717–729. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000002.

Steffansson, J., Nordstrom, P., & Jokinen, J. (2012). Suicide Intent Scale in the prediction of suicide. Journal of Affective Disorders, 136, 161–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.11.016.

Stevens-Watkins, D., Sharm, S, Knighton, J. S., & Oser, C. B. (2014). Examining cultural correlates of active coping among African American female trauma survivors. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 6, 328–336. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034116.

Taha, F., Zhang, H., Snead, K., Jones, A. D., Blackmon, B., Bryant, R. J., et al. (2015). Effects of a culturally informed intervention on abused, suicidal African American women. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 21, 560–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000018.

Taliaferro, L. A., Rienzo, B. A., Pigg, R. M. Jr., Miller, M. B., & Dodd, V. J. (2009). Spiritual well-being and suicidal ideation among college students. Journal of American College Health, 58, 83–90. https://doi.org/10.3200/jach.58.1.83-90.

Thompson, M. P., Kaslow, N. J., Short, L., & Wyckoff, S. (2002). The mediating roles of perceived social support and resources in the self-efficacy-suicide attempts relation among African American abused women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70, 942–949. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.70.4.942.

Utsey, S. O., Bolden, M. A., Williams, O. III.,, Lee, A., Lanier, Y., & Newsome, C. (2007a). Spiritual well-being as a mediator of the relation between culture-specific coping and quality of life in a community sample of African Americans. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 38, 123–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022106297296.

Utsey, S. O., Hook, J. N., & Stanard, P. (2007b). A re-examination of cultural factors that mitigate risk and promote resilience in relation to African American suicide: a review of the literature and recommendations for future research. Death Studies, 31, 399–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180701244553.

Valois, R. F., Zullig, K. J., & Hunter, A. A. (2015). Association between adolescent suicide ideation, suicide attempts and emotional self-efficacy. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 237–248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-013-9829-8.

Varvaro, F., & Palmer, M. (1993). Promotion of adaptation in battered women: a self-efficacy approach. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 5, 264–270. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-7599.1993.tb00882.x.

Walsh, K., Fortier, M. A., & DiLillo, D. (2010). Adult coping with childhood sexual abuse: a theoretical and empirical review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 15, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2009.06.009.

Widom, C. S., Czaja, S. J., & Dutton, M. A. (2014). Child abuse and neglect and intimate partner violence victimization and perpetration: a prospective investigation. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38, 650–663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.11.004.

Widom, C. S., Raphael, K. G., & DuMont, K. A. (2004). The case for presopective longitudinal studies in child maltreatment research: commentary on Dube, Williamson, Thompson, Felitti, and Anda (2004). Child Abuse & Neglect, 28, 715–722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.03.009.

Wildeman, C., Emanuel, N., LEventhal, J. M., Putnam-Hornstein, E., Waldfogel, J., & Lee, H. (2014). The prevalence of confirmed maltreatment among US children, 2004–2011. JAMA Pediatrics, 168, 706–713. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.410.

Woods-Giscombé, C. L. (2010). Superwoman schema: African American women’s views on stress, strength, and health. Qualitative Health Research, 20, 668–683. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732310361892.

Zhonglin, W., Kit-Tai, J., & Marsh, H. W. (2004). Structural equation model testing: cutoff criteria for goodness of fit indices and chi-square test. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 36, 186–194. doi: Retrieved from http://en.cnki.com.cn/Journal_en/F-F102-XLXB-2004-02.htm.

Zimmerman, M. A., Stoddard, S. A., Eisman, A. B., Caldwell, C. H., Aiyer, S. M., & Miller, A. (2013). Adolescent resilience: promotive factors that inform prevention. Child Development Perspectives, 7, 215–220. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12042.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (1R01MH078002- 01A2, Group interviews for abused, suicidal Black women) awarded to Dr. Nadine J. Kaslow.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to report.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kapoor, S., Domingue, H.K., Watson-Singleton, N.N. et al. Childhood Abuse, Intrapersonal Strength, and Suicide Resilience in African American Females who Attempted Suicide. J Fam Viol 33, 53–64 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-017-9943-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-017-9943-2