Abstract

Based on a recent survey and six focus groups, we use a mixed methods approach to examine the help-seeking behavior of Mexican female victims of partner violence in law-enforcement agencies and among family members. Support the family provides women is critically examined. The results of the study suggest that families are not always a source of support: 41 % of the women who turned to public authorities did not mention it to their families, and 11 % did not seek help because they feared their families would find out. Formal help-seeking at law-enforcement agencies is the only choice for many Mexican women since family support has a dual nature, positive and negative. Families may further victimize female victims since partner violence against women triggers the contradiction among core familistic values: individual expectations (family obligations and support) might go against family expectations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In Mexico, violence affects a significant number of women. According to data from the 2006 National Survey on the Dynamics of Household Relationships (Encuesta Nacional sobre la Dinámica de las Relaciones en los Hogares, ENDIREH), 10.72 % of Mexican women who are currently married, cohabiting, separated, or divorced have been subjected to sexual intimate partner violence (IPV), and 23.72 % have experienced physical violence at the hands of their current or previous partner. While the consequences and factors surrounding women’s experiences of IPV have been extensively studied in Mexico (Castro and Casique 2008; Oláiz et al. 2006; Rivera-Rivera et al. 2004), women’s reactions and strategies for seeking help (or not) from public institutions and social networks have not received the same degree of attention (exceptions in Agoff et al. 2007; Frías 2013).

Literature from around the world shows that social support networks and public institutions are instrumental in stopping IPV (Bosch and Bergen 2006; Frías and Angel 2007; Goodkind et al. 2003; Zakar et al. 2012). In Mexico, as opposed to other countries (Barrett and Pierre 2011; Fanslow and Robinson 2010), there are no studies using representative samples that make it possible to evaluate the extent of the search for help in informal networks, and especially in the family.

According to Parsons (1955), the family is an institution or organization based on predictable relationships, which represents a source of security and an instrument to confront a hostile world and difficult relationships. The security and trust family interactions provide are what have shaped the concept of familism (Heller 1970), a central trait of Mexican and Mexican-American culture and families (Harris et al. 2005; Heller 1970; Ingram 2007). Familism is the result of a set of normative beliefs that emphasize the centrality of the family and stress the obligations and support that nuclear family members owe to one another (Sabogal et al. 1987). According to Sabogal et al. (1987), familism is manifested in three main realms: the belief that family members must provide economic and emotional support to each other (familial obligations); the perception that family members are a dependable source of help, should be united and have close relationships; and, the belief that a family member’s behavior should meet family expectations (family as a referent).

In Mexico, 57.07 % of the women who have ever experienced partner violence did not seek formal help from law enforcement agencies or discussed their problems with their informal networks (Frías 2013). Among those who seek help, a considerable percentage of women do not turn to their families when subjected to partner violence, and turn instead to law enforcement agencies despite these institutions’ poor reputations and the little confidence they inspire (Davis 2006; Frías 2013). Therefore, the role of the family and the protective effects of familism in cases of IPV need to be reconsidered.

Partner violence against women triggers contradiction among core familistic values since individuals’ expectations (family obligations to support) might stand in opposition to the family’s expectations. Therefore, it is fitting to ask what factors are associated with women who experience IPV turning to their families for help. Or why do some of them turn to law enforcement agencies instead of turning to their families? This research attempts to answer these questions by using data from the ENDIREH and a focus group study, run in 2008, which explores women’s help-seeking behavior (six focus groups totaling 64 female victims of IPV). The combination of these two approaches is known as mixed methods research (Creswell 2003; Testa et al. 2011).

The underlying hypothesis is that in certain cases of IPV, the Mexican family may discourage women from seeking formal help and ultimately contribute to women’s re-victimization and defenselessness. The social structure of gender inequality that condones violence and holds women responsible for keeping the family together is manifested and repeated within the family, which is why family may not always be a benevolent source of support.

Partner Violence, Families and Seeking Help

Partner violence is one of the most brutal expressions of gender inequality. Male domination is sustained both in the private and public spheres by forms of violence that can be classified on a continuum (Walby 1990). At one extreme, there are the most brutal and roughest forms, such as physical and sexual violence, and on the other, the more subtle forms –and often the most effective ones for perpetuating oppression– like symbolic violence (Bourdieu 1998). Male violence against women is linked to structural gender inequality; various social agents and institutions reproduce these unequal relationship patterns and values (Dobash and Dobash 1979). Therefore, male violence against women within a relationship is a problem that includes a complex set of relationships with the social environment that can encourage the use of violence and be a factor in perpetuating it. Research suggests that families can play a fundamental role in reproducing and promoting the traditional gender norms, expectations, and sanctions imposed on women (Agoff et al. 2007; Clark et al. 2010; Erez et al. 2008; Marrs Fuchsel et al. 2012).

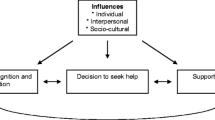

In an attempt to face the hardships of IPV and end the violence, some women seek help. Seeking help or support is a dimension of coping (Pearlin and Schooler 1978). Victims go through numerous stages until they manage to secure support: recognizing and defining the problem; deciding to seek help; and selecting a source of support (Liang et al. 2005). Liang et al. (2005) classify sources of support as formal and informal. Formal sources are public organizations (public authorities, the police, as well as prevention and assistance agencies), private organizations (medical, psychological), or non-profit organizations like women’s shelters. Informal sources of support consist among others of friends, family, acquaintances, and spiritual leaders. Sources of informal support might also provide women access to broader formal and informal networks (Bosch and Bergen 2006). The process of selecting a support provider involves an assessment of who the woman believes will provide the kind of support that fulfills her expectations. Other factors are her wish for privacy, potential stigmatization, the severity of the violence, and the prerequisite to end the relationship with the aggressor in order to receive help (Fugate et al. 2005; Hickman and Simpson 2003). The availability of family support networks, information about formal sources of support, and sufficient resources to access them determine where a woman seeks help (Rose et al. 2000; Zakar et al. 2012).

Since the presence, nature, and severity of violence in a couple’s relationship are in constant change (Frías and Angel 2007; Vickerman and Margolin 2008), recognizing and defining the problem is complex in itself. Its complexity further increases because in certain cultures and communities, violence is condoned and justified (Alberti Manzanares 2004; Krahe et al. 2005; Pérez Robledo 2004). For instance, in Mexico, almost 5 % of women perceive male violence toward women as a male’s right or prerogative (Frías 2013). Therefore, regardless of the type of violence women might experience, some women will not see it as a problem since their interpretative frameworks concur with the gender inequality structures (see Bourdieu 1998). Once women have identified the problem, the next step is to decide whether or not to ask for help. At this point, several variables of an individual, interpersonal, and situational nature, as well as the characteristics of the violence come into play (Fleury et al. 2000; Ingram 2007; Wolf et al. 2003). Not asking for formal help might also be a protective strategy, since seeking help can result in further harm to the woman. Regardless of the formal help-seeking process, women may choose to cope with the violence by using emotion-focused strategies, such as the use of religion, that allow them to manage the stressful situation (Zakar et al. 2012).

Some women may leave their abusive partners, communities, and families –which are very often not supportive- and move to another country to escape the abuse. It has been documented that some Mexican women who feel unsupported by both their families and public authorities move to the United States (Erez et al. 2008; Menjívar and Salcido 2002; Salcido and Adelman 2004). These women believe that, in a new setting, their anonymity will protect them from partner abuse. Some women come from countries where domestic violence is not considered a serious crime and they believe that IPV is not tolerated in the United States (Hirsch 2003) and more support is offered to women. Additionally, the 2000 Violence Against Women Act offers IPV victims the possibility of seeking asylum in the United States (Ingram et al. 2010; Menjívar and Salcido 2002).

In Mexico, there are limited data about women’s help-seeking behavior in cases of IPV. Existing data arise, on the one hand, from legal statistics and counts carried out by various public institutions (formal support) and, on the other from surveys, which measure both formal and informal support. The latter are more reliable. A recent study, which examines help-seeking strategies, shows that 26.1 % of Mexican women who are married, cohabiting, divorced, or separated have been subject to physical and/or sexual violence at the hands of their current or previous partners (Frías 2013). Of these, 22.84 % have sought help from law enforcement agencies at one time or another, and 11.03 %, from government agencies that provide assistance.

Most research in Mexico on seeking informal help from family or friends is qualitative. Lomnitz (1985) holds that in conditions of poverty, family networks compensate for the lack of material resources through exchanges based on reciprocity and trust that make survival possible. Family social networks further provide positive support to individuals with health problems (Castro et al. 1997). However, in situations in which women contravene gender role expectations or stereotypes, as in the case of pregnancy interruption (Castro and Erviti 2003; Erviti 2005) or partner violence (Agoff et al. 2007), families of both the woman and the man (by birth or marriage) often promote situations that harm women and render them unable to question or resist violence (Agoff et al. 2007; Agoff et al. 2006; Alberti Manzanares 2004; Castro 2004; Clark et al. 2010; Pérez Robledo 2004). Family members themselves, particularly mothers and mothers-in-law, contribute to replicating the problem by promoting traditional gender norms (Agoff et al. 2007; Bosch and Bergen 2006). The negative effects of these kinds of family relationships are related to two social processes included in social support: social control and relational demands and conflicts among the people involved in the process (see Castro et al. 1997). Therefore, one should not assume that a woman’s family is a source of unconditional support in all cases of IPV.

Methods and Data

This research uses a mixed-methods approach. The quantitative data is drawn from a recent survey, the second cross-sectional wave of the ENDIREH conducted in 2006. The quantitative analysis is complemented with qualitative data from six focus groups in order to obtain a deeper understanding of the family as a source of support. Although this type of research can be carried out with different methods, in this paper we use surveys as the primary method and focus group discussions as a source of follow-up data to illustrate some quantitative findings (Morgan 1996). Qualitative research reveals important insights into the subjective experience of violence, as well as enables a better understanding of the contexts and meanings associated with it. Therefore, presenting women’s testimonies in “their own words” along with the quantitative data implies a particularly enlightening contribution.

Qualitative Data and Methods

Six focus group discussions were conducted in Mexico City between March and April 2008. A recruitment agency contacted urban women attending public health services based on current or past experience of intimate partner violence in any of its forms. Participants were asked to participate in a focus group regarding their experiences of partner violence; 64 women between 20 and 65 years of age participated in the focus groups. On average, the women were 35.9 years old, 38.6 % were married, 21.2 % cohabiting, 28.1 % separated, 8.8 % divorced and 3.5 % single. More than half had reached high school or an equivalent level of schooling, 36.1 % secondary, 8.2 % primary, and only 3.3 % further than high school. All women but one had children, with an average of 2.2 per woman. They have an average income between three and five times the minimum wage (minimum wage stands at US $110 a month).

The characteristics of the violence experienced by participants in the focus groups are presented in Table 1. Results suggest that 76.8 % of them experienced physical violence, 43.9 % sexual violence, and almost all women reported suffering acts of emotional/psychological violence. For example, 59.6 % reported being hit or pushed; the same percentage disclosed being beaten with hands or an object. Four of every 10 of the women were forced to have sex against their will; two thirds felt afraid of their partners, 10 % were threatened with a gun or weapon, 1.8 % were shot, and 38.6 % reported that their partners forbade them to work or study.

Each discussion was conducted by a professional focus group moderator and co-moderated by one of the authors. The focus group discussion covered the following topics: violence as a normal occurrence in conflict resolution; tolerance of violence and types of violence; presence, type and quality of social networks; legitimation and justification of violence; women’s autonomy and empowerment; and justice and reparation.

The participants were contacted by company personnel of a company responsible for recruiting participants through their networks of key informants. Researchers were able to ensure that the women did not know each other. Their willingness to participate is likely to be associated with the limited governmental services addressing partner violence available for women. Women reported that they wanted to be heard and to share their experiences. Focus groups were conducted in a Gesell chamber set up by the company, thus guaranteeing participants’ security. All the participants gave their informed consent and were guaranteed anonymity. In addition, they were given a small economic stimulus for their time and transportation expenses (approximately 12 US dollars). They were also handed a list of public authorities, shelters, and agencies providing services to victims of family violence available to them.

The analysis of qualitative data is an inductive procedure based on the generation of meanings and theories from the data (Miles and Huberman 1994; Strauss and Corbin 1990). Analytical induction makes it possible to identify patterns or recurring themes, as well as to detect categories within the data. The analysis was centered on the issues most often repeated across the different groups. Then, using an open coding strategy, we mapped out the most prominent categories related to help-seeking and family support (Strauss and Corbin 1990).

Focus group discussions produce data resulting from a group’s sharing experiences, conversations, and interaction dynamics that arise out of the topics presented by the moderator, as well as those that emerge spontaneously. Individual statements or experiences are only taken into account when they produce some kind of echo, response, or silence in the group. This technique makes it possible to gain access to the process of social interaction itself (Kvale 1996; Morgan 1996), as well as the phenomenon of the fluidity of violence, that is, the different types of behavior and relationships which are expressed with different meanings (Pösö et al. 2008).

Social representations and ways of making sense of IPV are manifestations of the prevalent gender norms in a certain culture and social context. The group discussion technique aims to explore these shared experiences that emerged during group interactions in three different ways: as explicit knowledge, as feelings or emotions, and as practical knowledge, meaning latent and non-conscious knowledge that may evolve into profound insights during group discussions. Each group discussion offers privileged access to manifestations of gender, IPV, and help-seeking from the victims’ perspectives.

Quantitative Data and Methods

An analysis of the 2006 ENDIREH revealed information on currently married or cohabiting women subjected to IPV who sought formal and informal help. This nationally representative survey collected, among many other topics, extensive information on different forms of violence against women in different spheres, as well as attitudes and reactions toward the violence experienced. The analysis is based on those married or cohabiting women who have ever experienced either physical and/or sexual violence in their current relationship (N = 13,459). A woman is considered a victim of physical or sexual violence if her current partner has perpetrated at least one of the following acts against her. Physical violence: (1) being pushed or having one’s hair pulled out; (2) being tied up; (3) being kicked; (4) having something thrown at her; (5) being slapped, punched or beaten with hands, fists, or another object; (6) being choked; (7) having been cut with a knife; and/or (8) being shot at with a firearm. Sexual abuse consists of: (1) being forced to have sex against her will; (2) being forced to have any sexual activity against her will; (3) being forced to have sex under the threat of physical violence.

Results suggest that most married or cohabiting women have not suffered sexual or physical violence by their current partner (76.8 % of the weighted sample). However, 14.8 % only experienced physical violence, 6 % violence of a sexual nature, and 2.4 % have experienced both types of violence (details about the individual, sociodemographic, contextual and relational factors associated with IPV in this sample in Castro and Casique 2008). The structure of the survey, however, does not allow one to know if the woman sought help from her family networks after each violent act, which is a limitation. These women were mainly the objects of situational IPV (Johnson 2006).

Variables

The dependent variable in this analysis is seeking help in the face of intimate partner violence. This is a categorical variable with four categories: a) women who ask their families and public authorities for help; b) women who only ask their families for help; c) women who only turn to public authorities; and d) women who do not turn to either of them.

We identified four individual and relationship-related sets of characteristics associated with the experiences of IPV: socio-economic and demographic, violence background, household characteristics, and individual support of women’s rights as a proxy for egalitarian gender ideology. Among the personal history factors, the woman’s age and years of education are continuous variables measured in years. Employment is coded 1 if the respondent worked for pay during the week preceding the interview and 0 otherwise. Abuse background measures if the woman experienced physical violence perpetrated by a family member during childhood or adolescence. Marital status has two categories that assess whether a woman is cohabiting (coded 0) or married (coded 1).

The racial/ethnic diversity is a dichotomous variable that measures whether the woman speaks an indigenous language. By measuring those who speak an indigenous language in addition to or instead of Spanish, we are creating a proxy that allows us to identify, at least, the less acculturated indigenous individuals. The measure of socio-economic status follows the classification scheme developed by Echarri (2008), which is based on three household characteristics. The first is average years of education of the members of the household, the second refers to the occupational status of the household member with the highest potential income based on the average for that occupation, and the third involves basic household amenities. Based on these three characteristics, each household is assigned to one of four economic strata: very low, low, medium, and high.

Among the violence background and experiences, type of violence experienced is a variable with four categories that assesses the type and severity of the violence inflicted by the partner: moderate physical violence, severe physical violence, physical (any severity) and sexual violence, and only sexual violence. More than half of the women that compose this subsample (56.9 %) have experienced moderate violence (were pushed, kicked, hit, or had an object thrown at them) and 6.8 % suffered severe violence (was tied, choked, hurt with a weapon, knife or pocketknife), 25.9 % experienced both physical and sexual violence, and 10.4 % sexual violence exclusively. Experienced physical violence in family of origin records the respondents’ experience of physical violence during childhood or adolescence. Witnessed physical violence in family of origin assesses whether the respondent observed physical violence in her family while growing up. These two variables are coded 1 if an affirmative response was provided and 0 otherwise.

There are four independent situational variables. The number of residents in the household is a continuous variable that measures the number of people sharing the household with the interviewee. Urban is a dichotomous variable that assesses whether the woman lives in an urban setting of more than 2500 inhabitants (coded 1), or in a rural area (coded 0). The average age of the women’s children in the household has five categories: no children, children under five years of age, aged between five and 10 years, aged between 10 and 15 years, and aged between 15 and 18 years.

Finally, women’s support of women’s rights is a dichotomous variable based on women’s agreement or disagreement with all five statements about women’s rights: 1) “men and women must have the same right to make their own decisions”; 2) “men and women must have equal freedom”; 3) “men and women must have the same right to defend themselves and press charges in the event of violence or aggression”; 4) “women must have the possibility to make decisions about their own life”; and, 5) “women must have the right to a life free of violence.” Women’s support of women’s rights aims to capture some kind of subjective appropriation of women’s rights in a context in which legislation has attempted to de-construct a naturalized experience of women’s subordination (Agoff 2009).

Seeking Help After the Abuse

After the experience of IPV, more than half of the married or cohabiting women (57.07 %) did not seek formal help from law enforcement agencies or informal help within their family sphere. Only 25.64 % turned exclusively to their families; 9.89 %, only to public authorities, and the remaining 8.39 % turned to both the family and the Office of the Public Prosecutor or the police. The bivariate analysis presented in Table 2 shows several variables associated with the pattern of help-seeking. Among the women who did not seek help from law enforcement agencies or their families, we found a higher percentage of women who do not speak an indigenous language (56.26 %) than those who do (53.96 %), and a higher percentage of married women (56.99 %) than those in common law marriages (53.35 %). These women tend to be older, have lower levels of education and do not favor women’s rights very strongly compared to those who sought some kind of help from public authorities and/or their families.

As for women’s experiences with violence, among the variables measuring previous experiences of violence, a higher percentage of women who did not witness partner violence between their parents tend to refrain from turning to relatives or public authorities for help than those who did witness such violence (56.82 % vs. 55.14 %). The percentages of women who only suffered sexual violence or acts of moderate physical violence that do not seek help (67.69 % and 59.14 %) is higher than that of women who experienced severe physical violence (45.63 %) or physical violence along with violence of a sexual nature (47.64 %).

Several household characteristics are also associated with seeking help. A higher percentage of women without underage children at home tend not to seek help from either their families or public authorities than those who do. Likewise, a higher percentage of women who reside in rural areas tend not to seek help from either party than those who reside in urban areas (58.43 % vs. 55.34 %). Some women exclusively seek formal assistance from law enforcement agencies. This was more frequent among indigenous women than non-indigenous ones, among cohabiting women than married ones, among women who suffer from severe physical violence or physical and sexual violence than other kinds of violence, among women who witnessed violence in their family of origin than those who did not, among women whose children living at home are on average over the age of 10, and among those who reside in urban areas than those residing in rural areas.

Other women choose to only discuss their problem with their families. This is more frequent among women who do not speak an indigenous language, cohabiting women, younger women, women with higher levels of education, women who support women’s rights to a greater extent, and women who have only suffered moderate physical or sexual violence. It is significant that slightly more than one third of women with children under the average age of five only tell their families (34.28 %).

Among the 8.39 % of the women who turned to both formal help at law enforcement agencies and their families, there are more women who speak an indigenous language (9.44 %), who are unemployed (9.44 %), who endorse women’s rights (10.20 %), who have suffered severe physical violence or sexual and physical violence (20.02 % and 15.33 %), come from lower socioeconomic levels, and whose childrens’ ages average between 15 and 18 years (13.35 %).

Due to the complexity of social reality, it is necessary to examine this issue taking into account all the variables in the model at the same time. Two logistic regression models are presented in Table 3 in order to address the research questions concerning the correlates of seeking help from the family. The first model compares women who asked for help from law enforcement agencies and/or the family with those who did neither (reference category). It is plausible that not seeking help might be the result of a resistance strategy. These women are likely to be afraid of their partners, feel threatened, or they may even believe that the violence was somewhat insignificant. The second model compares the women who only turn to law enforcement agencies with those who turn to their families (regardless of whether they also turned to law enforcement agencies). This model profiles those women whose families theoretically do not offer positive support.

Model 1 reveals that there are several negative factors associated with asking for formal help from law enforcement agencies and/or or informal help from family. As a woman grows older and the number of residents in the household diminishes, the probability of a woman turning to any of these sources of support decreases. Likewise, employed and married women are also less likely to ask for some kind of help than unemployed or cohabiting women (the relative risk is respectively 15 and 9 % lower). Women who suffered physical violence while growing up are also less likely to ask for any kind of help (6 % lower, p < .10). When women suffer severe physical violence or a combination of physical and sexual violence, compared to women who experienced moderate violence, the relative risk of seeking some kind of help increases respectively by 76 and 67 %. Conversely, it is less likely that a woman will seek help when she has been a victim of sexual violence. The testimonies from the focus groups show how an increase in the severity of aggression can trigger seeking help. When violence increases in frequency and severity, it is no longer considered natural, leading women to undertake actions such as pressing charges against their assailants or calling public authorities:

I was used to [the fact] that he had to hit me. If I answered back, it was another blow. Then what happened is that he didn’t keep his strength in check. He didn’t weigh the consequences, and he lashed me against a piece of furniture we had and it cut open my head. When I saw the blood, it was really a shock… I acted. I didn’t call the patrol car again because the patrol car had come many times and they didn’t pay any attention to me. I called the judicial police [State Attorney General’s Office].

The likelihood of seeking some kind of help is also higher among women who speak an indigenous language, who live in urban areas, who have children under the average age of 10, as well as among those who fully endorse women’s rights.

The second model in Table 3 compares women who only turned to law enforcement agencies with those who told their family and/or sought help from law enforcement agencies (reference category). Turning to these agencies despite the commonly known problems regarding their service (Frías 2009, 2010) without seeking help from family members suggests that families may not always be a source of support. In the focus groups, many women shared personal accounts of seeking help from the justice system given their families’ lack of support and tendency to hold them accountable for the abuse they endured. It is likely that these experiences contributed to the women’s re-victimization:

When I went to file charges, the Ministerio Público [officer from the State Attorney’s Office] told me, “Your mom can render a statement. Your mom can attest!” And I told him, “Oh, no! Not my mom. My mom thinks I’m the worst person [in the world].” And he says, “But why?” And I say, “Because I’m all alone and I don’t want to be with the person who abuses me.” And he says, “What’s wrong with that?”

Results of this study suggest that women who experience severe physical violence or both physical and sexual violence are more likely to only seek help from law enforcement agencies (the relative risk increases by 152 and 73 %, respectively). However, when violence has exclusively been of a sexual nature, the likelihood of women seeking help of law enforcement without turning to their families invariably drops.

As women grow older, they appear to be less likely to seek help from law enforcement without informing their families. It is also less likely for married women to seek this kind of help compared to those cohabiting (16 % lower risk). However, women who speak an indigenous language and those who are employed are more likely to turn exclusively to public authorities than unemployed women or those do not speak an indigenous language. Living in an urban environment also increases the likelihood of a woman only making use of official agencies without telling her family. Having children under the age of 15 at home is also negatively linked to the likelihood of women turning to law enforcement agencies. However, in the focus groups, greater awareness of the potential harm to children emerges as a motivation for women to want to end the violent relationship.

You too, you can put up with it, because of preconceptions, for love, because you have someone beside you, for all that, for everything it represents, and it blinds you. It makes you close up. But when they touch your children, that’s when it gets to you and you become aware of the power you don’t have.

Family, Norms and Partner Violence Against Women

Violence against women occurs within a patriarchal social context (Dobash and Dobash 1979). In Mexico, the family, as a primary socializing agent, is likely to play a central role in preserving the patriarchal social system. The belief that family members should be united, have close relationships, and meet family expectations (Sabogal et al. 1987), are key factors in understanding negative family support in situations of IPV. Qualitative analyses of the focus groups suggest that social values and norms, which determine the expectations of women’s behavior and are reproduced and transmitted in the family environment, impress upon women the obligation to submit to violence. This might prevent them from seeking help from either formal or informal sources. In this study, women’s submission is expressed in three different non-exclusive ways: a) women’s responsibility to keep the family together, b) the justification of violence as punishment deserved for not fulfilling the prescribed gender roles, and/or c) tolerance toward abuse as part of every woman’s fate.

Numerous testimonies illustrate the mandate of submitting to violence that families impose to protect women’s reputations and the integrity of the family. Women are compelled to see their families of origin as a reference. Many women recount how their mothers were victims of physical violence arguing that as their own mothers endured violence, they are expected to as well. The traditional gender structure does not conceive of a woman separating from her partner. The family and the woman’s social respectability must be preserved, even in the event of violence. The experience described by a woman participating in a focus group shows how the family imposes constraints on its members when the reputation of the woman and her family is at stake.

G: I’ve been with my husband for 18 years because my mom tells me, “He is your husband. I only had one man and you should only have one man…” [Murmurs of agreement]. In other words, you can’t have several [men] because your mother brought you up that way. My mom says, “I have lived with your father all my life and you have to live with that man all your life.” Those are restrictions that your own family places on you. My mom also says, “Better the devil you know than the devil you don’t,” which is also a mistake.

The next testimonies illustrate how family members, especially mothers, see women and their own daughters without a male partner as sexually available and incapable of taking care of themselves:

E: Regarding the [process of] separation [from my husband], it was hard because sure enough mothers don’t want you to separate and they force you to… well, they try to force you to go back to the husband, telling you to return, asking what you are going to do without a husband… I think older women think that without a man, there’s no respect. I always told my mom, “Respect is something you give yourself; you can accept it or not…”

M: And that’s what my mom told me, “You’re just not going to be able to do anything…” and I went back to my mother’s house and finished vocational school as a construction technician and they offered me a job as a drafter and as an architectural calculation technician, but I couldn’t take it because neither my mother nor my siblings wanted to help me out by watching my children for a while. It wasn’t even the whole day. They didn’t want to help me so that I would go back with the man. So it is hard, isn’t it? Because in your own home, in your own family, they want to suppress you, telling you with actions to go back to the man. For me it was hard to go back to him because he wanted to abuse my kids… sexually… that’s why I separated… [Everyone murmurs.]

These testimonies illustrates how the family not only represents a void in the support system, but it openly places obstacles along the way for a woman empower herself and get ahead. Keeping family unity intact is a supreme value to be protected, above the integrity of the woman and her children. Moreover, the belief that violence is an expression of love towards the woman still persists; although as time passes, this is becoming more and more obsolete.

Parents and grandparents always tell us, “If he scolds you or hits you, whatever he does to you, accept it. If he humiliates you, accept it, Why? Because he does it because he loves you” [Laughter, talking at the same time] Nonsense!

In other cases, the mandate of submitting to violence imposed by the family is centered on the idea that violence is the natural, common, inherent fate of women. The mandate of submission to male violence is justified as a punishment because she chose him to be her partner, sometimes against her family’s will, or because she does not comply with traditional gender norms and roles. The following testimonies illustrate this and underscore that some families attribute responsibility to women for their own abuse.

P: My mom would tell me it was my cross…and since it was my responsibility, it was my cross to bear

C: They would tell me, “You chose him… you chose him… now you put up with it…”

E: That’s why [experiencing partner violence] is so embarrassing… because you chose him. One says “Why was I so dumb and stupid?”

Another way of imposing submission to violence is through the meanings attributed to marriage and the importance of its preservation as a family tradition. Quantitative data show that compared to married women, cohabiting women are more likely to seek help and especially to turn to public authorities. In Mexico, the responsibility of keeping the family together falls on the woman. When faced with the possibility of losing her family’s respectability, the stigma of being a divorced woman, and defying religious norms that forbid divorce, she is likely to sacrifice herself and put up with the abuse rather than facing stigma and being ostracized.

X: I was brought up “the old-fashioned way”. I had a church wedding and a civil ceremony, like my grandparents, and like my mother. My mother died at the age of 32 and she put up with a lot from my father. I try to cope with the situation because that’s my motto: “Until death do us part…” I don’t know, it’s the so-called old-fashioned way. Society marks you out when you’re divorced. For example, in my family everyone was married by the church and in his family too, and there is no divorce or anything like that. His relatives also have fights and even worse than ours. In his family, there are cases of beatings, and they draw up official reports and everything, but they’re still together…

P: My mom would tell me “Go back, go back” and I stood my ground, “No and no… and no and no…” It’s hard work because you are fighting against, well, against those people around you as well as your feelings, and your doubts because [in your family] you’ve never seen anyone divorced. In my family everyone is married; all my siblings. I’m the only one who is divorced and they look at you like, “Whoa, you’re weird.” In fact, they don’t hang around much with me and it’s hard in that respect, in terms of society, in terms of family...

According to the women participating in the focus groups, in the event of serious partner violence resulting in severe harm to the woman, birth families and families by marriage differ in the support they provide to women in terms of seeking help in public agencies or pressing charges against her abuser. In such cases, birth families, as opposed to families by marriage, tend to provide positive support. The following testimony gives a glimpse into how little solidarity there is among females, because a family’s interest in defending its members, even when they are guilty of severe violence, comes first:

M: I took [legal] action, because I had second degree injuries. They [police] went to my house where the whole thing took place to take pictures and there they told me what I was going to do… He was assigned to the [Federal District] Preventive Southern Prison, and he was sent to that prison… At the last minute, you get these feelings of guilt. At that moment you feel guilty. His parents told me how bad I was, and I quarreled with all his family. My dad was furious. I think that if he had seen him outside, he would have almost killed him… My dad said, “Look, he almost took out your eye!” My brother too. I remember my mother being super upset, and the girl was too. I remember it was something really, really serious, horrible! His mother… I think that as women, we should back each other up. His mother, instead of backing me up, told me I was crazy, that I had hit myself, that her son wasn’t capable of that. Then… of course! I felt really bad, and I went to see him. It’s really awful… [Her voice cracks] but the proceedings continued.

The survey data shows that some women do not turn to public authorities because of reasons linked to their families: 11.4 % of the women victims of physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence do not go to public authorities so that “their family doesn’t find out”, which suggests that a considerable percentage of women endure IPV in silence. Likewise, 2 % claimed that they did not turn to law enforcement agencies because “their family convinced her not to do it”. These figures resonate in the accounts of the women in the focus groups:

G: For me, it was really hard to get out. I think that from the beginning of the marriage, he started lowering my self-esteem and he would tell me [that] “You are a nobody, you’re good for nothing.” And, unfortunately, you believe it because who can you tell? You go and tell your mother-in-law, and your mother-in-law tells you “don’t tell anyone”.

It should be noted that in some cases, “family persuasion” for not seeking help can be well-intentioned. Due to reported corruption in law enforcement agencies and the widespread knowledge that women are treated badly, it is likely that in some cases, families provide support by discouraging women from seeking help from the authorities due to the perceived risk of re-victimization. The testimonies presented above illustrate how, in cases of IPV, an individual’s familistic expectations tend to collide with societal and family gender expectations and demonstrate how the family is not always a source of support for women seeking help. It is likely that in these types of families, women prefer turning to law enforcement agencies or simply decide not to seek help.

Discussion

This research highlights the fact that the family may not always act as a source of support for women who suffer physical and/or sexual IPV. In fact, only slightly more than one third of women disclosed their experiences of abuse to their families. Most women sought formal help from neither law enforcement agencies nor their families (56.1 %), and 9.9 % turned exclusively to public authorities. In other words, almost two out of every three women (64.6 %) take a different course of action than disclosing to their families. In addition, as demonstrated in focus group discussions, even when they turn to their families, the family is not always a positive source of support. This study illustrates the tensions associated with the familistic obligation of helping family members, the mandate of being united and having close relationships and, the belief that family members’ behaviors should meet family expectations.

This research challenges the concept of familism, articulated around the security and trust of family member interactions (Heller 1970) and presents the negative side of families by examining the phenomenon of IPV against women. The testimonies of women participating in several focus groups highlight how some families impose upon their members –including women- certain cultural norms that reflect and reproduce the patriarchal social structure. These norms aim to keep the family together, protect women’s honor, condone violence as an expression of love and affection or as punishment for transgressing traditional gender roles, and conceptualize partner violence as a shared women’s experience.

Quantitative data reveal several individual characteristics associated with seeking help. Younger women are more likely to seek both formal and informal sources of support and are more likely to exclusively seek help from public authorities rather than turning to their families. This finding might reflect younger women’s resistance to family mandates of subordination.

Another relevant finding is the relationship between women’s help-seeking behavior and their support of women’s rights. When women concur that males and females have the same rights, it is more likely that they will seek help. The act of asking for help, as specified in the model established by Liang et al. (2005), implies that women have already recognized and defined the problem, which is significant since greater support for women’s rights is likely to promote greater recognition of IPV as a problem.

This study further demonstrates how a woman’s marital status may influence how she deals with IPV. Married women are less likely to seek help, and when they decide to do so, they are more likely to turn to families. The fact that a smaller proportion of married women seek help suggests two explanations. The first refers to the institution of marriage and the social value given to it, and the second is linked to women’s emotional investment in the relationship. In Mexico, as in other societies, marriage is considered a sacred institution by both family and friends; therefore, a married woman may have greater responsibility in trying to make the relationship work than a woman in a common-law marriage (Goodkind et al. 2003).

Furthermore, women who speak an indigenous language are more likely to ask for help and turn only to the authorities instead of the family than women who do not speak an indigenous language. It is likely that the normalization or acceptance of violence among members of some indigenous communities can lead women to seek help from sources other than their own families. Women may also be affected by patrilocality typically found in unions and marriages among indigenous groups.

The authorities to whom some indigenous women turn for help are probably indigenous community authorities who impart a type of justice controlled by the community and based on tradition. The community authorities’ framework of action centers principally on the conciliation of the parties (see Alberti Manzanares 2004). It has been documented that some of the indigenous women who disobey gender norms and take decisions autonomously do not dare ask their families for help since putting up with partner violence is considered punishment for acting independently and making decisions of their own (Vallejo Real 2004).

The nature of the violence women suffer is another important variable that explains help-seeking behavior. Moderate violence appears to be tolerated up to a certain point. However, when women suffer severe physical violence or both physical and sexual violence, it is more likely that they will seek help. In the event of both physical and sexual violence, it is more likely that women turn to law enforcement agencies rather than to their families.

This study also shows that women who only suffer sexual violence are less likely to ask for any kind of help. In the focus groups, there was no mention of situations of sexual violence. In Mexico, marital rape was not jurisprudentially recognized by the Supreme Court until late 2005 (see Frías 2008). It should be noted that a considerable percentage of Mexican women (11 % according to 2003 ENDIREH data) still believe it is their duty to have sexual relations with their husbands, even if it is against their will. Therefore, some women may have difficulty labeling some acts as sexual abuse. In addition, it has been reported that when women turn to law enforcement authorities, they are often advised to resolve the conflicts and violence using sex and seduction (Frías 2010). In this context, it is unlikely that, in cases of partner sexual violence, women will turn to public authorities for help or tell their families.

Another important finding in this study refers to the presence and age of children in the home of the women subjected to physical and/or sexual violence. It is more likely that women ask for help if they have children under the average age of 10. Nevertheless, as the average age of children decreases, the probability of abused women turning to family support rather than to public authorities increases. Regardless of their socio-economic level, women show the same likelihood of seeking help and of turning solely to the authorities. Lastly, proximity to public authorities for women who live in urban areas makes it easier to turn to said authorities, or even prefer them as a source of support over their families.

Focus group discussions explored other sources of support such as in-laws, friends, and social acquaintances. The participants revealed differences in support from birth families and families by marriage. They agreed that their husbands’ families are less supportive of them. In addition, they reported feeling positively supported by other individuals, such as friends or neighbors, who contest and challenge violence. In these relationships, exchanges of solidarity and mutual acknowledgement are made possible due to the absence of the conflicts of interest, power imbalances, and expectations found in interfamily relations.

Limitations

This study has been restricted to examining help seeking from a formal source (public prosecutor agencies) and an informal one (the family). This does not mean that women who did not turn to either of these two sources did not seek help of any kind since they could have sought help from friends, assistance agencies, churches, neighbors, or healthcare professionals, among others.

The results of this study present some limitations stemming from the use of secondary data. First of all, due to social desirability, the percentage of women who have suffered physical and/or sexual violence is probably higher than that reported here; hence, it has been impossible to study these women’s patterns of help-seeking. Secondly, in the case of a woman seeking help from formal sources at law enforcement agencies and informal sources in the family, the family’s reaction in terms of rendering assistance or not is unknown. However, theoretically, the choice of support provider is based on women’s expectations (Liang et al. 2005). A third limitation refers to the fact that we do not have information about the event that led to the decision of seeking formal or informal help, since women may have experienced violence on several occasions. Nor do we know when the violence took place or whether they have always turned to the same sources of support or to different ones. In order take into account these significant factors, further survey research into women’s experiences seeking help, the response they receive upon doing so, and women’s reaction to said help (if help is conceded) is needed. Further information on support structures and family characteristics is also necessary. Finally, as only urban women participated in the focus groups, it is likely that their experiences are not entirely shared by women residing in rural settings.

Conclusion

This study has examined how socio-demographic, family, and situational factors, as well as characteristics of abuse, are linked to help seeking behavior among women who experience IPV. Understanding the behavior of women who suffer violence is of key importance to at least three objectives of individual and political nature. The first is to provide adequate services to women who suffer IPV. Secondly, to acknowledge the multiple victimizations women experience at the hands of their romantic partner, family, and public authorities. In cases of undocumented women running away from their abusers, unsupportive families and authorities as well as legislation on deporting undocumented individuals, endanger these women and might lead to further victimization by their former partners and relatives. Some countries, such as Spain or the United States, have enacted legal initiatives to protect undocumented victims of gender and partner violence. Advocates and those who work directly with victims of partner violence need to inform them of their rights and increase public awareness. This would guarantee that undocumented women fleeing from partner violence are not returned to face a reality of a lack of opportunities and further violence. Finally, the findings of this research can be instrumental for the State (the ultimate protector of individual rights) to design public policies aimed at providing better assistance and prevention. This is significant in the United States, where at least 31 million individuals are of Mexican origin, and in Mexico, where public actions and policies that presume the family support to women in the event of partner violence should be revised.

References

Agoff C. (2009). La Abierta Competencia entre el Reconocimiento Jurídico y la Valoración Social. Civitas, 9(3), 402–417.

Agoff C., Herrera C., & Castro R. (2007). The weakness of family ties and their perpetuating effects on gender violence. A qualitative study in Mexico. Violence Against Women, 13(11), 1206–1220.

Agoff C., Rajsbaum A., & Herrera C. (2006). Perspectivas de las Mujeres Maltratadas sobre la Violencia de Pareja en México. Salud Pública de México, 48(Suppl 2), S307–S314.

Alberti Manzanares, P. (2004). ¿Qué es la Violencia Doméstica para las Mujeres Indígenas en el Medio Rural? In T. Fernández de Juan (Ed.), Violencia contra la Mujer en México (pp. 19–49). México: CNDH.

Barrett, B. J., & St. Pierre, M. (2011). Variation in women’s help seeking in response to intimate partner violence: findings from a canadian population-based study. Violence Against Women, 17(1), 47–70.

Bosch K., & Bergen M. B. (2006). The influence of supportive and nonsupportive persons in helping rural women in abusive partner relationships become free from abuse. Journal of Family Violence, 21, 311–320.

Bourdieu P. (1998). Masculine Domination. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Castro R. (2004). Violencia contra Mujeres Embarazadas. Tres Estudios Sociológicos. Cuernavaca: CRIM-UNAM.

Castro R., Campero L., & Hernández B. (1997). La Investigación sobre Apoyo Social en Salud: Situación Actual y Nuevos Desafíos. Rev. Sáude Publica, 31(4), 425–435.

Castro R., & Casique I. (2008). Violencia de Género en las Parejas Mexicanas. Análisis de Resultados de la Encuesta Nacional sobre la Dinámica de las Relaciones de los Hogares 2006. Mexico: INMUJERES.

Castro R., & Erviti J. (2003). Las Redes Sociales en la Experiencia del Aborto: Un Estudio de Caso con Mujeres de Cuernavaca (México). Estudios Sociológicos, XXI(3), 585–611.

Clark C. J., Silverman J. G., Sahrouri M., Everson-Rose S., & Groce N. (2010). The role of the extended family in women’s risk of intimate partner violence in Jordan. Social Science & Medicine, 70, 144–151.

Creswell J. W. (2003). Research design. qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Davis D. E. (2006). Undermining the rule of law: democratization and the dark side of police reform in Mexico. Latin American Politics and Society, 48(1), 55–86.

Dobash R. E., & Dobash R. P. (1979). Violence against wives: a case against the patriarchy. New York: Free Press.

Echarri, C. J. (2008). Desigualdad Socioeconómica y Salud Reproductiva: Una Propuesta de Estratificación Social Aplicable a las Encuestas. In S. Lerner & I. Szasz (Eds.), Salud Reproductiva y Condiciones de Vida en México (Vol. 1, pp. 59–113). México: El Colegio de México.

Erez E., Adelman M., & Gregory C. (2008). Intersections of immigration and domestic violence: voices of battered immigrant women. Feminist Crimininology, 4(1), 32–56.

Erviti J. (2005). El Aborto entre Mujeres Pobres. Cuernavaca: UNAM-CRIM.

Fanslow J. L., & Robinson E. M. (2010). Help-seeking behaviors and reasons for help seeking reported by a representative sample of women victims of intimate partner violence in New Zealand. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25(5), 929–951.

Fleury R. E., Sullivan C. M., & Bybee D. (2000). When ending the relationship does not end the violence. Violence Against Women, 6(12), 1363–1383.

Frías S. M. (2008). Measuring structural patriarchy: toward the construction of a gender equality index in Mexican States. Social Indicators Research, 88(2), 215–246.

Frías S. M. (2009). Gender, the state and patriarchy: partner violence in Mexico. Saarbrücken: VDM.

Frías S. M. (2010). Between agency and structure: advocacy and family violence in Mexico. Women’s Studies International Forum, 33(6), 542–551.

Frías S. M. (2013). Strategies and help-seeking behavior in law-enforcement offices among mexican women experiencing partner violence. Violence Against Women, 19(1), 24–49.

Frías S. M., & Angel R. J. (2007). Stability and change in the experiences of partner violence among low-income women. Social Science Quarterly, 88(5), 1281–1306.

Fugate M., Landis L., Riordan K., Naureckas S., & Engel B. (2005). Barriers to domestic violence help-seeking. Violence Against Women, 11(3), 290–310.

Goodkind J. R., Gillum T. L., Bybee D., & Sullivan C. M. (2003). The impact of family and friend’s reactions on the well-being of women with abusive partners. Violence Against Women, 9(3), 347–373.

Harris R. J., Firestone J. M., & Vega W. A. (2005). The interaction of country of origin, acculturation, and gender role ideology on wife abuse. Social Science Quarterly, 86(2), 463–483.

Heller P. L. (1970). Familism scale: a measure of family solidarity. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 37, 73–80.

Hickman L. J., & Simpson S. S. (2003). Fair treatment or preferred outcome? the impact of police behavior on victim reports of domestic violence incidents. Law and Society Review, 37(3), 607–633.

Hirsch J. S. (2003). A Courtship after Marriage (1 ed., ). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Ingram E. M. (2007). A comparison of help seeking between latino and non-latino victims of intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women, 13(2), 159–171.

Ingram M., McClelland D. J., Martin J., Caballero M. F., Mayorga T., & Gillespie K. (2010). Experiences of immigrant women who self-petition under the violence against women act. Violence Against Women, 16(8), 858–880.

Johnson M. P. (2006). Conflict and control. gender symmetry and asymmetry in domestic violence. Violence Against Women, 12(1), 1003–1018.

Krahe B., Bieneck S., & Moller I. (2005). Understanding gender and intimate partner violence from an international perspective. Sex Roles, 52(11/12), 807–827.

Kvale S. (1996). Interviews: an introduction to qualitative research interviewing. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Liang B., Goodman L. A., Tummala-Narra P., & Weintraub S. (2005). A theoretical framework for understanding help-seeking processes among survivors of intimate partner violence. American Journal of Community Psychology, 36(1–2), 71–84.

Marrs Fuchsel C., Murphy S. B., & Dufresne R. (2012). Domestic violence, culture, and relationship dynamics among immigrant mexican women. Affilia, 27(3), 263–274.

Menjívar C., & Salcido O. (2002). Immigrant women and domestic violence. common experiences in different countries. Gender and Society, 16(6), 898–920.

Miles M. B., & Huberman A. M. (1994). Qualitative Data Analysis. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Morgan D. L. (1996). Focus Groups. Annual Review of Sociology, 22, 129–152.

Oláiz G., Rojas R., Valdez-Santiago R., Franco A., & Palma O. (2006). Prevalencia de Diferentes Tipos de Violencia en Usuarias del Sector Salud en México. Salud Pública de México, 48(Suppl 2), S232–S238.

Parsons, T. (1955). The American Family: Its Relation to Personality and Social Structure. In T. Parsons & R. Bales (Eds.), Family Socialization and Interactional Process (pp. 273–203). Glencoe, Ill.: Free Press.

Pearlin L. I., & Schooler C. (1978). The Structure of Coping. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 19(2), 2–21.

Pérez Robledo, F. M. (2004). Pegar “de Balde”/Pegar “con Razón”. Aproximación Etnográfica a las Prácticas Violentas hacia las Mujeres en Comunidades Tojobales. In T. Fernandez de Juan (Ed.), Violencia contra la Mujer en México (pp. 51–68). Mexico: CNDH.

Pösö T., Honkatukia P., & Nyqvist L. (2008). Focus groups and the study of violence. Qualitative Research, 8(1), 73–89.

Rivera-Rivera L., Lazcano-Ponce E., Salmerón-Castro J., Salazar-Martínez E., Castro R., & Hernández-Ávila M. (2004). Prevalence and determinants of male partner violence against mexican women: a population-based study. Salud Pública de México, 46(2), 113–122.

Rose L. E., Campbell J., & Kub J. (2000). The role of social support and family relationships in women’s responses to battering. Health Care for Women International, 21, 27–39.

Sabogal F., Marín G., Otero-Sabogal R., Vanoss-Marín B., & Perez-Stable E. J. (1987). Hispanic familism and acculturation: what changes and what doesn’t. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 9(4), 397–412.

Salcido O., & Adelman M. (2004). ‘He Has Me Tied with the Blessed and Dammed Papers’: Undocumented-Immigrant Battered Women in Phoenix, Arizona. Human Organization, 63(2), 162–172.

Strauss A., & Corbin J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Testa M., Livingston J. A., & VanZile-Tamsem C. (2011). Advancing the study of violence against women using mixed methods: integrating qualitative methods into a quantitative research program. Violence Against Women, 17(2), 236–250.

Vallejo Real I. R. (2004). Usos y Escenificaciones de la Legalidad ante Litigios de Violencia hacia la Mujer Maseual en Cuetzalan, Puebla. In M. Torres-Falcón (Ed.), (pp. 379–414). Mexico: El Colegio de Mexico.

Vickerman K. A., & Margolin G. (2008). Trajectories of Physical and Emotional Marital Aggression in Midlife Couples. Violence and Victims, 23(1), 18–34.

Walby S. (1990). Theorizing Patriarchy (2nd. ed.,). Cambridge, MA: Basil Blackwell Ldt.

Wolf M. E., Ly U., Hobart M., & Kernic M. (2003). Barriers to seeking police help for intimate partner violence. Journal of Family Violence, 18(2), 121–129.

Zakar R., Zakar M. Z., & Krämer A. (2012). Voices of strenght and struggle: women’s coping strategies against spousal violence in Pakistan. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27(16), 3268–3298.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Frías, S.M., Carolina Agoff, M. Between Support and Vulnerability: Examining Family Support Among Women Victims of Intimate Partner Violence in Mexico. J Fam Viol 30, 277–291 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-015-9677-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-015-9677-y