Abstract

Despite the well-documented negative consequences for children experiencing violence perpetrated by their fathers against their mothers, little is known about how characteristics of exposure to violence are related to child–father contact after parental separation. In this study, we (a) describe contact patterns between children and fathers after parental separation and (b) analyze links between patterns of violence and contact in a sample of child witnesses to intimate partner violence in Sweden. Information about 165 children (aged 3–13 years) was obtained from their mothers, who had been subjected to violence by the child’s father. In 60 % of the cases, the parents had joint custody. Results suggest that children without contact with their father have witnessed more violence than children with contact. However, when they do have contact, previous violence against the mother does not correlate either with amount or type of child–father contact. Instead, high socioeconomic status and negotiation skills correlated positively with amount of contact.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The problematic nature of contact after parental separation in contexts of intimate partner violence (IPV) has recently attracted greater attention from policy makers, practitioners, and researchers (Hunt 2004). IPV often continues after separation—or even increases, at least during the first phase (e.g. Fleury et al. 2000)—and is accompanied by fear and concern for safety and well-being among both women and children (Shalansky et al. 1999). Since the vast majority of children remain with their mother as the residential parent (e.g. Juby et al. 2007; Manning et al. 2003; Statistics Sweden 2012), a wide range of arrangements are made to preserve child–father contact (overnight stays, days out, supervised visitation, etc.) (Hunt 2004; Smyth et al. 2004; Smyth et al. 2012).

Research on general samples has found more frequent and regular contact with the non-resident parent to be associated with benefits for the child, such as fewer adjustment problems (Dunn et al. 2004). However, little research has focused on violent fathers’ involvement with their children after separation (Pate 2008), despite well-grounded knowledge about the possible negative consequences of IPV on children’s health and well-being (e.g. posttraumatic stress, psychological and behavioral problems, parental attachment, and school difficulties) (Holt et al. 2008; Howell 2011; Lang and Smith Stover 2008; Levendosky et al. 2003; Wolfe et al. 2003) and about the overlap between IPV and child abuse (Bourassa 2007; Hamby et al. 2010; Herrenkohl et al. 2008). On the one hand, child contact arrangements often directly or indirectly provide fathers who have a strong need for control with opportunities to use the child–father relationship to that end, for instance by turning the child against the mother, keeping track of her activities (Beeble et al. 2007; Hardesty and Ganong 2006; Hayes 2012; Walby and Allen 2004), or keeping her busy handling repeated accusations of child abuse, for example (Miller and Smolter 2011). On the other hand, child witnesses to IPV generally experience little interest from their fathers (Cater and Forssell 2014) and some research indicates that child–father contact may decline over time because violent fathers lose interest in their children if the contact does not provide them with access to the mother (Cheadle et al. 2010; Edleson 1999; Hardesty and Ganong 2006).

Previous research has studied several factors influencing the amount of child–father contact after separation: the father’s income, conjugal/parental trajectory, and level of satisfaction with existing arrangements (Swiss and Le Bourdais 2009); the father’s age (Castillo et al. 2011); the mother’s remarriage (Furstenberg et al., 1983; Seltzer and Bianchi, 1988; Seltzer 1991); or the child acquiring a stepfather (Juby et al. 2007). In addition, the father’s remarriage (Furstenberg et al. 1983), the birth of a baby within the father’s new union (Cooksey and Craig 1998; Manning et al. 2003), as well as the child’s gender and age at separation (Cheadle et al. 2010; Le Bourdais et al. 2002) have also been shown to have an impact. Geographical issues such as the father being incarcerated, (Cooksey and Craig 1998), not residing with the child (Castillo et al. 2011), and distance between the non-resident parent’s home and that of the child (Blackwell and Dawe, 2003) also affect child–father contact. Sparse or no activity or engagement from non-residing fathers has been explained by factors such as a loss of fathering identity, which results in becoming a “visitor” in the child’s life (Kruk 1993; Stone and McKenry 1998); and the mother’s attitude towards men and fathering, i.e. “maternal gatekeeping” (Allen and Hawkins 1999; Fagan and Barnett 2003; Hauser 2012). Other factors can also be assumed to influence child–father contact. As an example, fathers’ psychological problems have been shown to be connected to their perpetrating violence, with more frequent aggression being displayed if they meet diagnostic criteria (Shorey et al. 2012). On the other hand, because children tend to be worse off if their mother is in too poor emotional shape to take care of them (Martinez-Torteya et al. 2009), mothers experiencing psychological problems may seek additional child-care help from the father. Drug or alcohol abuse can also affect parents’ amount of contact with their children (Waller and Swisher 2006), with substance abuse by the father potentially reducing child–father contact, and substance abuse by the mother increasing it. However, the factors influencing children’s contact with a father who has previously engaged in IPV have—to our knowledge—not been studied.

In research about spousal separation, the terms “conflict” or “high level conflict” are sometimes used (see for example Figure 1 in Leite and McKenry 2002; see also Johnson and Ferraro 2000). However, such terminology can obscure possible physical force, injuries, and power inequalities between the partners and thus obstruct the understanding of the impact of violence. Research is therefore needed regarding how characteristics of exposure to explicit forms of violence perpetrated by fathers are related to child–father contact after separation.

This is especially important to study in a country such as Sweden, because in Nordic countries the laws on child custody after separation give high priority to maintaining contact between the child and the non-resident parent after separation (Hakovirta and Broberg 2007). The aim of this study is therefore (a) to describe patterns in the contact between children and (previously) violent fathers after parental separation, and (b) to analyze the link between patterns of violence and child–father contact in a sample of child witnesses to IPV in Sweden. Does the amount or severity of the violence correlate with the amount or kind of contact between child and father after separation?

Method

Participants

The participants in this study are a subsample drawn from an evaluation of Swedish Interventions for Children who have witnessed Violence Against their Mother (the SICVAM project) commissioned by the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare. The evaluation aimed to investigate the effects of different treatment programs for child witnesses of IPV (Broberg et al. 2011). The participants were recruited through different service units, e.g. child psychiatry and the social services. Criteria for inclusion in SICVAM were that (a) the mother had experienced violence from an intimate partner, (b) the child was aged 3–13 years at inclusion, and (c) the mother was able to answer research questions in Swedish. Exclusion criteria were (a) the perpetrator not being the child’s legal father, (b) the father being deceased, (c) the child living with foster parents, (d) a stepmother (and not the biological mother) being the object of violence, (e) the child living with its mother and father, and (f) the child being under the care of a service unit that demanded no child–father contact during treatment. To avoid spurious results, one child from each family meeting those criteria was randomly included in the study,

By this procedure, the final subsample for this study came to consist of 165 mothers who provided information about themselves, their child’s father (i.e. the perpetrator of violence), and their child. The sample comprised 102 boys (61.8 %) and 63 girls (38.2 %). These 165 children had a mean age of 7.72 years (SD = 2.90) at the time of the first data collection and a mean age of 4.86 years (SD = 3.06, range 0–12 years) at the time of parental separation. Almost all the children (95.7 %) were born in Sweden. Of the mothers, 69.7 % were born in Sweden, 9.1 % in another European country, and 21.2 % in a country outside of Europe. Of the fathers, 55.2 % were born in Sweden, 15.7 % in another European country, and 29.1 % in a country outside of Europe.

Procedures

Independent interviewers interviewed all children’s mothers either in the home, at the university, at a treatment unit, or elsewhere (e.g. mother’s workplace), according to the wishes of the mother. At time of service-unit enrollment, the mothers answered questions about IPV, child–father contact, socioeconomic status (SES), both parents’ psychological health and drug and alcohol abuse, and demographics, as well as a dichotomous question about child abuse; 3–5 months later they answered a questionnaire about child abuse. Participation was voluntary and no financial compensation was provided. Attrition in the sample was generally small; however, eight mothers did not fill out the questionnaire concerning IPV at the first interview. Furthermore, because the questionnaire concerning child abuse was filled out during the second interview, the number of respondents for this measure was affected by the attrition between the first and second interviews. This resulted in a loss of information on 47 children (28.5 %). However, out of those 47 children, approximately one third (n = 16) had not been subjected to violence by their father, according to information from the first interview.

The project was approved by the Ethical Review Board, and informed consent was obtained from all participating mothers.

Measures

IPV. Violence was assessed with the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale, 39 items, (CTS-2) (Straus et al. 1996) using a version slightly modified by (a) excluding the questions concerning the mother’s possible violence against the father, and (b) adding follow-up questions to 20 chosen items about whether the child had witnessed the violence (by seeing, hearing, or other means). In CTS-2, five subscales of women’s experience of violence were used in the initial analysis. The presence of any specific item during the relationship was coded “1″ and its absence was coded “0″ on a dichotomous scale. Thus, a higher score indicates more violence (except for the negotiation subscale). Internal reliability was calculated for every subscale and index with Cronbach’s alpha (α). The subscales and their scoring range were as follows: physical assault (0–12, α = 0.862), sexual coercion (0–7, α = 0.840), physical injury (0–6, α = 0.720), and negotiation (0–5, α = 0.689). Concerning negotiation, one item was excluded (“My partner said he was sure we could work out a problem”), since it decreased the internal reliability. Concerning psychological aggression (0–8), the internal reliability was considered too low (α = 0.448). After excluding one item (“My partner stomped out of the room or house or yard during a disagreement”), which decreased the internal reliability index considerably, the internal reliability increased to α = 0.538. Because this was still considered unacceptable, this subscale was not used and the specific item (“My partner stomped…”) was excluded from the total index (see below). Instead, we analyzed each item on the psychological aggression subscale individually. We also created a variable measuring the total amount of violence against the mother (0–32, α = 0.903), in which the subscale of negotiation is excluded, but all the other subscales, including psychological aggression, are summed up for each individual.

What the child had witnessed was measured as presence (1) or absence (0) of the types of incidents specified in the 20 follow-up questions in CTS-2. Thus, a higher score equals having witnessed more kinds of violence. The items in CTS-2 were divided into physical assault (range 0–14, α = 0.863) and psychological aggression (range 0–6, α = 0.594). However, the latter were not used because the internal reliability was considered too low. For the child witnessing violence, a variable measuring the total amount of violence witnessed by the child (range 0–20, α = 0.872), which includes both psychological and physical violence, was also created.

Child abuse

Child abuse was measured by a dichotomous question (yes/no) at the time of first data collection and again 3–5 months later, using a Swedish version of Conflict Tactics Scale: Child (CTS-C) modified to contain 14 items (Straus et al. 1998; Straus 2007). CTS-C was divided into three subscales (scoring range in parentheses) where the presence of a specific item was coded “1” and an absence of violence was coded “0”: physical violence (ranging from 0–8, α = 0.902), psychological violence (0–4, α = 0.763), and sexual violence (0–1, only one item). For CTS-C there is also a factor called “total abuse,” which is the sum of the three subscales (0–14, α = 0.901). Thus, a higher score indicates the child being subjected to more kinds of violence.

Contact

Contact between father and child was measured through a cross-sectional questionnaire in which the mother answered questions about the frequency of (a) face-to-face contact (with or without supervision), (b) telephone contact (verbally or by text messages), or (c) written contact (i.e. e-mail, chat, letters) on the scale “never/almost never,” “occasionally,” “every other month,” “every other week,” and “daily.” These were coded from 0–4, (0 = never/almost never, 4 = daily). In addition, a sum of scores for contact was constructed from the four different types. This score ranges from 0–12, because the children in the study had either supervised or unsupervised face-to-face contact. A higher score thus suggests a higher frequency of contact.

Socioeconomic status (SES)

The socioeconomic measure used for mothers and fathers in this study is that of Hollingshead (Hollingshead 1975). This is a combined measure of current labor market status ([1–9] × 5) and educational level ([1–7] × 3) and the total score ranges from 8 to 66. A higher score means having a more secure position in the labor market (and possibly also a better salary) as well as a higher education level.

Psychological health

Mothers’ psychological health was measured with the Brief Symptom Inventory (Derogatis and Melisaratos 1983), a shorter version of the Symptom Checklist (SCL90), which is used to measure general psychological ill health. Both the total score and the nine subscales were used. The revised Impact of Event Scale (IES-R) (Creamer 2003) was used to measure indications of post-traumatic symptoms, with both total score and the three subscales (avoidance, intrusion, and hyperarousal) being used separately. In this study, information about the father’s psychological problems was obtained from the mother and coded as either 1 (psychological problems) or 2 (no psychological problems).

Drug or alcohol abuse

Perpetrators’ alcohol use was measured on a four-grade scale (1 = total abstainer, 2 = responsible drinker, 3 = problematic drinker, 4 = alcohol abuser), and drug abuse on a dichotomous question (yes/no). Mothers self-reported any ongoing or previous drug or alcohol abuse by answering a single yes-or-no question.

Demographics

Information concerning background data (age, civil status, etc.) was obtained through a background interview with the mother.

Data Analytic Strategy

All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 20. The following confounding variables were controlled for: (a) child’s age, (b) child’s age at time of separation, (c) child’s gender, (d) number of years since the relationship ended, (e) whether the violence has ended and, if so, how long ago, (f) mother’s and father’s drug or alcohol abuse, (g) mother’s and father’s psychological health, (h) mother’s and father’s civil status, and (i) mother’s and father’s socioeconomic status (SES).

Results

In the text below, the contact between child and father is referred to as “contact with father”; note that the father is also equated with the perpetrator of the violence. In the sample, 60.6 % of the children were in the joint custody of both parents; the rest of the children were in the sole custody of the mother, except for one child, legal custody of whom had been granted to the father. For 57.0 % of the children (n = 94), the violence against the mother was still ongoing (in some form) at the time of the first interview. The first two themes below—“Types and amount of contact” and “Factors differentiating children with and without contact”—are based on the sample as a whole (N = 165 children), whereas the third and fourth themes (“The relation between the type and amount of violence and contact” and “Child abuse and contact”) are based solely on the group of children that did have contact with their father (n = 122).

Types and Amount of Contact

The majority of the children had contact with their (violent) father in one way or another, and 20 children (12.1 %) spent alternating weeks with each parent. Four children lived with their father only. For the vast majority of the children, however, the mother was the residential parent (n = 141, 85.5 %).

The children who had face-to-face contact (either supervised or unsupervised) constitute approximately 68 % of the total sample (n = 113). Table 1 shows that of these, about 13 % (15 children) had supervised, and 87 % (n = 98) unsupervised contact. Most of the children who had unsupervised contact met their father at least every other week. In the group with supervision, contact seems to be a bit less frequent.

More than half of the total sample of children (50.9 %, n = 84) had no telephone or written contact with their father. However, 47.3 % of the children had both face-to-face and telephone/written contact. Most common was telephone calls or texting between child and father, with more than a third doing this at least every other week (see Table 2). Although letters and the Internet provide multiple possibilities to stay in touch with a non-resident father, they were only used by 18 children (approximately 11 %) in the sample. A small number of children (5.5 %) had no face-to-face contact, their only contact with their father being by phone or writing (n = 9). Notable, however, is that the amount of contact says nothing about the quality of the contact; as pointed out by several researchers (Amato and Gilbreth 1999; King and Sobolewski 2006; Whiteside and Becker 2000), quality rather than quantity of contact is probably more important in order to achieve a positive outcome for the child.

Factors Differentiating Children with and without Contact with their Fathers

The results show that approximately one in four children (26.1 %) had no contact at all with their father, neither face-to-face nor by phone or writing. When comparing the contact group with the no-contact group, we used independent sample T-tests (2-ways) or in cases of dichotomous questions, such as child’s gender, Pearson’s chi-2 (χ2). The groups do not differ concerning child’s age and gender; child’s age at time of separation; mother’s age, SES, civil status, and country of origin; father’s age, civil status, and country of origin; father’s alcohol or drug abuse; and father’s psychological problems. The means for total violence against mothers (CTS-2) are also similar in the two groups, and it does not matter whether or not the violence has ended. Table 3 shows, however, that the children who did not have contact also differ in several ways from those who had some kind of contact. First, fathers of children without contact have lower mean scores for SES (p = 0.003). Second, the group of children without contact has a higher mean score for sexual coercion against their mothers (differing approximately one point on a 0–7 scale, p = 0.023) indicating more and/or more severe sexual violence. Third, the groups also differ on the negotiation scale, indicating for example higher levels of arguing skills and ability to listen to one’s partner among the fathers with whom the children have contact. However, the difference is quite small (0.7 on a 0–5 scale, p = 0.018).

To estimate differences between the two groups (with and without contact) with data constituted by two dichotomous questions, Pearson’s chi-square (χ2) was used. Children whose mothers had ongoing psychological problems (self-rated, dichotomous question) were less likely to have contact with their father after separation. Approximately 65 % (n = 33) of the children whose mothers had psychological problems had contact, as compared to 81 % (n = 87) of those whose mothers deemed themselves psychologically healthy (χ2 (1) = 4.70, p < 0.05), which may indicate that a well-functioning mother can serve as catalyst to enable child–father contact after separation (cf. “gate opening” Trinder 2008).

The chi-square tests revealed a nearly significant result, indicating that when the mother had been threatened, the child was less likely to have contact with the father (see Table 4) (χ2 (1) = 3.67, p =0.055). No other item from the subscale of psychological aggression differs between the two groups.

Analyses of the child’s witnessing of different types of psychological aggression revealed several differences between children with and without contact respectively, and these were in line with the results found in the mother’s experiences. The children without contact had witnessed threats against their mother to a greater extent (χ2 (1) = 5.30, p < 0.05), and were more likely to have witnessed something being destroyed on purpose (χ2 (1) = 8.49, p < 0.01). Furthermore, children who had been abused by their father (posed as a dichotomous yes/no question, Table 4) were less likely to have contact with him after separation (χ2 (1) = 5.92, p < 0.05)—a somewhat expected result, perhaps, considering the possible risk of continued violence against the child after separation found by Radford and Hester (2006) and Brown (2006). Hence, violence—specifically sexual coercion and child abuse—seems to make a difference when deciding whether to completely terminate contact.

The Relation between Type and Amount of Violence and Contact

Above, we found that some forms of violence (sexual coercion against the mother and abuse of the child) were correlated with the existence of child–father contact. However, because some children whose mothers had been sexually coerced or who had experienced child abuse had contact with their father, we also analyzed the relationship between the types and amount of violence and the amount of contact. The following results are solely based on the group of children that did have contact with their father (n = 122). When investigating the relationship between the amount of different types of violence and the amount of contact, the correlation coefficient Spearman’s Rho (r s ) was used in most cases, since the material mainly consists of categorical data. For statistical controls, we used partial correlation. Because the items in the subscale of psychological aggression can only assume two values, 0 and 1 (cf. Field 2009), correlations were instead calculated with Cramer’s V for these items.

Neither of the subscales of violence (either mother’s experience or child’s witnessing) correlates with contact of any type. A few associations can be noted between amount of contact and specific items from the subscale of psychological aggression, however the strengths of the associations are low to moderate overall. For example, there is a negative association between the item, “My partner threatened to hit or throw something at me” and face-to-face unsupervised contact, concerning the mother being subjected to the event (V = 0.299, p < 0.05). As mentioned above, this item differed (though not statistically significantly) between the contact group and the no-contact group, indicating that threats may be viewed as a stronger reason for restricting contact with the father than other types of psychological aggression, such as verbal insults.

The total amount of violence the mother had experienced correlates negatively (r s = −0.19 p < 0.05) with unsupervised face-to-face contact. However, this correlation disappears when controlling for the father’s and mother’s SES. Also notable is that there is a significant correlation between the father’s SES and the amount of face-to-face unsupervised contact between father and child (r s = 0.22, p < 0.05). No such correlations can be found between mother’s SES and child–father contact. Indications of this association between fathers’ SES and contact after separation have been found in other studies, where lower income is mentioned as an obstacle to maintaining contact for non-resident fathers (Swiss and Le Bourdais 2009).

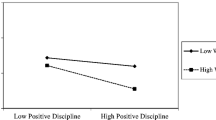

The total amount of child–father contact (face-to-face and telephone/written) correlates positively (r s = 0.21, p < 0.05) with the negotiation subscale, and this correlation remains even after statistically controlling for background factors. The negotiation subscale also correlates positively with face-to-face contact (r s = 0.20, p < 0.05), (supervised and unsupervised), though not with only telephone or written contact separately. Neither of the correlations are strong, but they do indicate that fathers with better skills in listening to the mother and taking her opinions into consideration also have more contact, particularly face-to-face, with their children. We furthermore found a positive correlation for one of the items in the psychological aggression subscale, namely between the child witnessing, “My partner stomped out of the room or house or yard during a disagreement” and face-to-face contact (V = 0.309, p < 0.05), which supports the possibility that this may be perceived by the mother as a relatively constructive way of resolving conflicts, rather than a violent act.

The fact that contact does not correlate with violence, but does correlate both with the father’s and mother’s socioeconomic status and with negotiation, may indicate that there is a group of fathers who get/have more contact with their children regardless of the severity or amount of violence they have perpetrated. This may be related either to the father, apart from his violent behaviors, meeting the child’s need by for example exhibiting empathy and/or responsibility, or to this group being more verbally skilled and able to convince the mother, the social worker, or the court that more contact is in the child’s best interest. The fact that they tend to have better education and jobs may also be an indication that some preconceptions about violent fathers—as “typically” being unemployed, for example—may skew the judgment of social workers or family law secretaries working with contact disputes, and prevent them from recognizing or interpreting certain actions as instances of violence when they occur in “atypical violent families.”

The Relationship Between Child Abuse and Contact

As mentioned earlier, no contact at all between child and father is more common in the group of children who had been subjected to child abuse by their father. Even so, a substantial number of children in the group who do have contact have been subjected to violence (psychological, physical, and/or sexual) by their father. Among the children whose mothers answered “Yes” to the dichotomous question of violence against the child (n = 102), approximately 51 % still have face-to-face unsupervised contact, the majority at least every other week (see Table 5).

When looking more closely at a possible relationship between unsupervised face-to-face contact, as well as contact by telephone or Internet, and more specific types of child abuse, no correlations were found. However, preliminary correlations were found for increased amounts of supervised contact for children who had been subjected to any of the types of violence (physical r s = 0.45 p < 0.01; psychological r s =0.36 p < 0.01; sexual r s =0.39 p < 01). This correlation disappears, however, for physical and psychological child abuse when controlling for the time that has elapsed between the cessation of violence against the mother (if it has ended) and the occasion of the first interview (physical violence p = 0.093 and psychological violence p = 0.107). It is notable, however, that for sexual violence the correlation remains (p = 0.024). A plausible reason for these varying outcomes is that the group of children who had supervised contact and had been subjected to any of the types of child abuse is too small (n = 4 to n = 11) for this kind of statistical analysis.

In conclusion, the study shows that many children have contact with their fathers regardless of the amount of violence their fathers have perpetrated against their mothers. An exception to this general conclusion is constituted by the children who had no contact at all. The children in this group had witnessed more sexual violence against their mothers and were more likely to have experienced child abuse. No other correlations between the types or amounts of violence and contact could be found. Instead, another pattern appears, namely that children are more likely to have contact with fathers who negotiate more and have higher SES. This might indicate that risk assessment was not a central consideration when decisions were being made about contact, or that possible positive fathering characteristics were taken into account.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to describe patterns in the contact between children and (previously) violent fathers after parental separation, and to analyze the link between patterns of violence and child–father contact in a sample of child witnesses to IPV in Sweden. This study shares some specific strengths and weaknesses with other studies focusing on IPV. It was limited by at least four methodological shortcomings. First, the sample was not randomly selected, which limits the generalizability of the results. Second, the data was obtained only from the mothers. This limits the reliability of some of the data, especially concerning the fathers’ psychological health and possible alcohol and drug use. Third, we were unable to control for some potentially significant variables; for example, geographic distance and fathers’ possible incarceration, which may hinder face-to-face contact (Cooksey and Craig 1998). Furthermore, we could not control for the child’s own wishes, which may affect the level of contact. Fourth, some of the instruments are somewhat blunt. As an example, the fathers’ psychological problems were measured by one dichotomous question (yes/no). Furthermore, CTS-2 only affords limited insight into many common aspects of IPV, such as economic abuse, manipulation involving children, isolation, intimidation, and ongoing systematic patterns of violence. The instrument has also been criticized for combining more and less severe forms of violence and for providing little insight into the frequency of violence previous to the past year. These limitations need to be kept in mind when interpreting our findings that suggest there is no connection between the amount and type of violence and the amount and type of child–father contact. Connections might be found using another instrument. In addition, non-significant findings, for example concerning cases of supervised contact, may be due to limitations associated with the relatively small sample size and limitations of the instruments for measuring IPV, and should therefore be investigated further, rather than being dismissed.

Despite its methodological limitations, the present study breaks new ground. It is unique in examining the link between violence and actual child–father contact and thus greatly contributes to a much-needed field of knowledge. The strengths of this study include its elicitation of information from a hard-to-research group about several areas that are often overlooked in research. As an example, the inclusion of a variety of types of contact makes it possible to gain greater insight into nuances in the contact patterns, including telephone or written contact. Also, in addition to information about the violence directed towards the mother, violence experienced by the child (though reported by the mother) is included (cf. Morrison 2009). Furthermore, despite its primary focus being on IPV, the study provides insight into the role that child abuse plays in child–father contact in these families.

Some findings of this study are in line with those in the broader body of literature. Specifically, most of the children do have face-to-face contact with their father, often combined with telephone/written contact, and the majority sees their father every other week (cf. Jonsson et al. 2001). A smaller number of children only have written or telephone contact with their father. Altogether, these findings are not surprising, given that Swedish law gives high priority to supporting contact between the child and the non-resident parent after separation (Hakovirta and Broberg 2007).

Other findings of this study are unexpected. Although previous research has shown that some children seem resilient when it comes to both the long- and short-term consequences of violence (Howell 2011), a considerable amount of research has proven that the greater the amount of violence to which children have been exposed, the more likely they are to experience adjustment problems (Howell 2011). Hence, given that children have the right to be protected from all forms of violence (UNCRC, Article 19), the greater the amount of violence the father has perpetrated, the stronger the reason to protect the child from it. However, this study found no connection between the amount and type of violence against the mother and the amount and type of child–father contact. Also, previous research has found that child–father contact may be a platform for continuing to perpetrate violence against the mother (Beeble et al. 2007; Hardesty and Ganong 2006; Walby and Allen 2004). Even though this study did not find any correlation between the amount of violence and the amount of child–father contact, the violence against (at least) the mother was ongoing in half of the cases studied. Thus, further investigation is needed to ascertain whether the presence of more violence is used as an argument to protect the child by reducing contact, whether less contact leads to a reduction in the amount of violence, or whether the varying relationships between the amount of violence and the amount of contact are due to family-specific differences.

Approximately, one in four children in this study had no contact with their father at all. These children differed in several ways from those who did have contact. First, the no-contact children were more likely to have been subjected to child abuse by their father, and their mothers had experienced more sexual coercion. Hence, some types of violence may be used as reasons for ending child–father contact. Second, the fathers of children with no contact had lower mean SES and lower negotiation scores, indicating less use of reasoning or negotiation to deal with conflicts, whilst higher SES and negotiation scores correlated positively with more contact. In a similar vein, the item indicating that fathers had angrily left the room or the house during a conflict was positively correlated with contact. Taken together, this may suggest that a subgroup of fathers are able to listen to the mother’s opinions and feelings to a larger extent and to solve conflicts through other means than violence, and that they tend to have more contact with their children and are less at risk of having no contact at all. This may indicate that fathers’ social position and social skills are factors that facilitate the existence and amount of contact between children and previously violent fathers, a connection previously found in general samples (e.g. Swiss and Le Bourdais 2009). With these findings, the present study also raises questions about the potential risks and benefits of child–parent contact in families affected by IPV. As “fathers’ statements of concern may be poor indicators of their intentions to refrain from abusive behavior” (Rothman et al. 2007, p. 1179), the link found in this study between socioeconomic status and negotiation skills and contact raises concerns whether these fathers are more empathetic and flexible or merely better persuaders.

The children that had been subjected to child sexual abuse had more supervised face-to-face contact with their fathers. However, we found no other correlation between the amount of different types of child abuse and the amount of contact. Hence, almost half of the children who had been abused by their father had unsupervised face-to-face contact with him after separation. We do not know whether the child abuse had stopped, but even if it had, the child–father relationship may be affected by earlier child abuse by the father.

In sum, the findings of this study indicate that most children who have witnessed IPV have contact with their fathers, and the amount of violence does not appear to influence contact decisions. Instead, higher SES and more use of negotiation seem to be linked to greater amounts of contact. On the other hand, violence seems to have played a role when deciding to terminate the contact, since the children with no contact at all are more likely to have been subjected to child abuse and their mothers have experienced more sexual violence. These results raise important questions about how decisions concerning child–father contact are made in cases of IPV.

Clinical Implications and Future Directions

This study points to the importance of differentiation and deeper reflection when it comes to violence and contact decisions (cf. Calder 2004). The fact that child–father contact is related to the father’s social position and negotiation skills rather than to the amount of IPV he has perpetrated indicates that making contact decisions that protect children from future exposure to violence is a delicate task.

Better knowledge about the many and severe potential consequences for children of IPV exposure (Holt et al. 2008; Howell 2011; Lang and Smith Stover 2008; Norman et al. 2012), and about the risk of future violence that previous violence entails (cf. Fleury et al. 2000) as well as screening for IPV might help practitioners make adequate risk assessments in custody, residence, or contact disputes or investigations (cf. e.g. Holtzworth-Munroe 2011; Brännström 2007). Such practice could better equip practitioners to deal with the delicate issue of balancing children’s need for contact with both parents against their need for protection from all forms of violence. They can thereby also avoid the simplistic assumption that contact with both parents after separation is always in the child’s best interest (cf. Holt 2011; Lessard et al. 2010; Swiss and Le Bourdais 2009) and instead take seriously the notion that the family can actually be dangerous for children (Shea Hart 2010). The study specifically indicates that it might be helpful to make more extensive use of other forms of contact, e.g. telephone contact or, in more extreme cases, written contact that has been edited by an outsider, e.g. a social worker. Through such measures, professionals could make the father responsible for avoiding violence and acting safely (cf. Scott and Crooks 2004) while at the same time protecting the child from future exposure to IPV.

Although this study reports modest statistical results, the findings highlight the need for further research on this topic. Empirical studies of what happens to children during and after separation in families affected by IPV are urgently needed. Future research needs to address how the quality and organization of contact, such as its form (face-to-face, telephone/written, or supervised, etc.) or amount, are affected by physical, psychological, or sexual forms of pre- and post-separation violence against the mother and/or the child, as well as how different patterns of contact with the father are related to the health and well-being of child witnesses to IPV. Specifically, the understanding of the relationship between IPV and child–father contact after separation would benefit from future studies that include reports from the children themselves in order to also take into consideration how the child perceives the contact.

References

Allen, S. M., & Hawkins, A. J. (1999). Maternal gatekeeping: mothers’ beliefs and behaviors that inhibit greater father involvement in family work. Journal of Marriage and Family, 61, 199–212. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/353894

Amato, P. R., & Gilbreth, J. G. (1999). Nonresident fathers and children’s well-being: a meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family, 61, 557–573. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/353560

Beeble M. L., Bybee D., & Sullivan C. M. (2007). Abusive men’s use of children to control their partners and ex-partners. European Psychologist., 12, 54–61. doi:10.1027/1016-9040.12.1.54.

Blackwell A., & Dawe F. (2003). Non-resident parent contact (). London: The Department for Constitutional Affairs, Office for National Statistics.

Bourassa C. (2007). Co-occurrence of interparental violence and child physical abuse and its effect on the adolescents’ behavior. Journal of Family Violence, 22, 691–701. doi:10.1007/s10896-007-9117-8.

Broberg, A., Almqvist, K., Almqvist, L., Axberg, U., Cater, Å. K., Forssell, A. M., Sharifi, U. (2011). Stöd till barn som bevittnat våld mot mamma. Resultat från en nationell utvärdering. [Support to children who have witnessed violence against their mothers. Results from a national evaluation study.] Department of Psychology, Gothenburg University.

Brown, T. (2006). Child abuse and domestic violence in the context of parental separation and divorce: New models of intervention. In C. Humphreys & N. Stanley (Eds.), Domestic violence and child protection: Directions for good practice (pp. 155–168). London: Jessica Kingsley.

Brännström L. (2007). Riskbedömningar i samband med utredningar om vårdnad, boende och umgänge [Risk assessments in investigations concerning custody, place of residence, and contact] Rapport från Institutet för utveckling av metoder i socialt arbete IMS. Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen.

Calder M. C., Harold G. T., & Howarth E. L. (2004). Children living with domestic violence. Towards a framework for assessment and intervention (). Lyme Regis: Russell House Publishing.

Castillo J., Welch G., & Sarver C. (2011). Fathering: the relationship between fathers’ residence, fathers’ sociodemographic characteristics, and father involvement. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 15, 1342–1349. doi:10.1007/s10995-010-0684-6.

Cater Å., & Forssell A. M. (2014). Descriptions of fathers’ care by children exposed to intimate partner violence (IPV) – relative neglect and children’s needs. Child and Family Social Work, 19, 185–193. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2206.2012.00892.x.

Cheadle, J. E., Amato, P. R., & King, V. (2010). Patterns of nonresident father contact. Demography, 47, 205–225. Retrieved from http://springerlink.bibliotecabuap.elogim.com/article/10.1353/dem.0.0084

Code on Parents and Children, 1949:381, chapter 6

Cooksey, E. C., & Craig, P. H. (1998). Parenting from a distance: the effects of paternal characteristics on contact between nonresidential fathers and their children. Demography, 35, 187–200. Retrieved from http://springerlink.bibliotecabuap.elogim.com/article/10.2307/3004051

Creamer, M., Bell., R., & Failla, S. (2003). Psychometric properties of the Impact of Event Scale-revised. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 41, 1489–1496. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.07.010

Derogatis L. R., & Melisaratos N. (1983). The Brief Symptom Inventory: An introductory report. Psychological Medicine, 13, 595–605. doi:10.1017/S0033291700048017.

Dunn J., Cheng H., O’Connor T. G., & Bridges L. (2004). Children’s perspectives on their relationships with their nonresident fathers: influences, outcomes and implications. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45, 553–566. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00245.x.

Edleson J. L. (1999). Children’s witnessing of adult domestic violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 14, 839–870. doi:10.1177/088626099014008004.

Fagan J., & Barnett M. (2003). The relationship between maternal gatekeeping, paternal competence, mothers’ attitudes about the father role, and father involvement. Journal of Family Issues, 24, 1020–1043. doi:10.1177/0192513X03256397.

Field A. (2009). Discovering Statistics Using SPSS (). London: SAGE.

Fleury R. E., Sullivan C. M., & Bybee D. I. (2000). When ending the relationship does not end the violence: Women’s experiences of violence by former partners. Violence Against Women, 6, 1363–1383. doi:10.1177/10778010022183695.

Furstenberg, F. F., Winquist Nord, C., Peterson, J. L., & Zill, N. (1983). The life course of children of divorce: Marital disruption and parental contact. American Sociological Review, 48, 656–668. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2094925

Hakovirta, M., & Broberg, M. (2007). Parenting from a distance: Factors connected to the contact between children and a non-resident parent. Nordisk Sosialt Arbeid, 27, 19–33. Retrieved from http://www.idunn.no/ts/nsa

Hamby S., Finkelhor D., Turner H., & Ormrod R. (2010). The overlap of witnessing partner violence with child maltreatment and other victimizations in a nationally representative survey of youth. Child Abuse & Neglect, 34, 734–741. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.03.001.

Hardesty J. L., & Ganong L. H. (2006). How women make custody decisions and manage co-parenting with abusive former husbands. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 23, 543–563. doi:10.1177/0265407506065983.

Hauser O. (2012). Pushing daddy away? A qualitative study of maternal gatekeeping. Qualitative Sociology Review, 8, 34–Retrieved from http://www.qualitativesociologyreview.org/ENG/index_eng.php59.

Hayes B. E. (2012). Abusive men’s indirect control of their partner during the process of separation. Journal of Family Violence, 27, 333–344. doi:10.1007/s10896-012-9428-2.

Herrenkohl T. I., Sousa C., Tajima E. A., Herrenkohl R. C., & Moylan C. A. (2008). Intersection of child abuse and children’s exposure to domestic violence. Trauma Violence Abuse, 9, 84–99. doi:10.1177/1524838008314797.

Hollingshead, A. B. (1975). The four factor index of social position. Unpublished manuscript, Department of Sociology, Yale University, New Haven, CT. Swedish translation and revision by Broberg, A. (1984/1992), Institution of psychology, Gothenburg university.

Holt S., Buckley H., & Whelan S. (2008). The impact of exposure to domestic violence on children and young people: A review of the literature. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32, 797–810. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.02.004.

Holt S. (2011). Domestic abuse and child contact: Positioning children in the decision-making process. Child Care in Practice, 17, 327–346. doi:10.1080/13575279.2011.596817.

Holtzworth-Munroe A. (2011). Controversies in divorce mediation and intimate partner violence: A focus on the children. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 16, 319–324. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2011.04.009.

Howell K. H. (2011). Resilience and psychopathology in children exposed to family violence. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 16, 562–569. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2011.09.001.

Hunt J. (2004). Child contact with non-resident parents. In Family policy briefing 3 (). Department of Social Policy and Social Work: University of Oxford.

Johnson M. P., & Ferraro K. J. (2000). Research on domestic violence in the 1990’s: Making distinctions. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 948–963. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00948.x.

Jonsson, J. O., Östberg, V., Brolin Låftman, S., & Evertsson, M. (2001). Barns och ungdomars välfärd. [Welfare of children and youth]. Report SOU 2001:55. Stockholm: Fritzes.

Juby H., Billette J.-M., Laplante B., & Le Bourdais C. (2007). Nonresident fathers and children: Parents’ new unions and frequency of contact. Journal of Family Issues, 28, 1220–1245. doi:10.1177/0192513X07302103.

King V., & Sobolewski J. M. (2006). Nonresident fathers’ contributions to adolescent well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 537–557. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00274.x.

Kruk E. (1993). Divorce and disengagement: Patterns of fatherhood within and beyond marriage (). Halifax, Canada: Fernwood.

Lang J. M., & Smith Stover C. (2008). Symptom patterns among youth exposed to intimate partner violence. Journal of Family Violence, 23, 619–629. doi:10.1007/s10896-008-9184-5.

Le Bourdais, C., Juby, H., & Marcil-Gratton, N. (2002). Keeping in touch with children after separation: The point of view of fathers. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 21, 109–130. Retrieved from http://cjcmh.metapress.com/app/home/main.asp

Leite R. W., & McKenry P. C. (2002). Aspects of father status and postdivorce father involvement with children. Journal of Family Issues, 23, 601–623. doi:10.1177/0192513X02023005002.

Lessard, G., Flynn, C., Turcotte, P., Damant, D., Vézina, J.-F., Godin, M.-F., … Rondeau-Cantin, S. (2010). Child custody issues and co-occurrence of intimate partner violence and child maltreatment: Controversies and points of agreement amongst practitioners. Child & Family Social Work, 15, 1365–2206. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2206.2010.00705.x

Levendosky A., Huth-Bocks A., Shapiro D., & Semel M. (2003). The impact of domestic violence on the maternal-child relationship and pre-school-age children’s functioning. Journal of Family Psychology, 17, 275–288. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.17.3.275.

Manning W. D., Stewart S. D., & Smock P. J. (2003). The complexity of fathers’ parenting responsibilities and involvement with nonresident children. Journal of Family Issues, 24, 645–667. doi:10.1177/0192513X03252573.

Martinez-Torteya C., Bogat A. G., von Eye A., & Levendosky A. A. (2009). Resilience among children exposed to domestic violence: The role of risk and protective factors. Child Development, 80, 562–577. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01279.x.

Miller S. L., & Smolter N. L. (2011). “Paper abuse”: When all else fails, batterers use procedural stalking. Violence Against Women, 17, 637–650. doi:10.1177/1077801211407290.

Morrison, F. (2009). After domestic abuse: Children’s perspectives on contact with fathers. Centre for Research on Families and Relationships, Briefing 42. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/1842/2795

Norman, R. E., Byambaa, M., De, R., Butchart, A., Scott, J., & Vos, T. (2012). The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Medicine, 9 (11), 1–31. Retrieved from www.plosmedicine.org/

Pate Jr. D. J. (2008). Child support enforcement and father involvement among victims of intimate partner violence. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 17, 42–58. doi:10.1080/10926770802250785.

Radford L., & Hester M. (2006). Mothering through domestic violence (). London: Jessica Kingsley Publications.

Rothman E. F., Mandel D. G., & Silverman J. G. (2007). Abusers’ perceptions of the effect of their intimate partner violence on children. Violence Against Women, 13, 1179–1191. doi:10.1177/1077801207308260.

Scott K. L., & Crooks C. V. (2004). Effective change in maltreating fathers: Critical principles for intervention planning. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11, 95–111. doi:10.1093/clipsy/bph058.

Seltzer J. A. (1991). Relationships between fathers and children who live apart: The father’s role after separation. Journal of Marriage and Family, 53, 79–Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/353135.

Seltzer J. A., & Bianchi S. M. (1988). Children’s contact with absent parents. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 50, 663–Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/352636.

Shalansky C., Ericksen J., & Henderson A. (1999). Abused women and child custody: the ongoing exposure to abusive ex-partners. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 29, 416–426. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.00904.x.

Shea Hart A. (2010). Children’s needs compromised in the construction of their “best interest”. Women’s Studies International Forum, 33, 196–205. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2009.12.004.

Shorey R. C., Febres J., Brasfield H., & Stuart G. L. (2012). The prevalence of mental health problems in men arrested for domestic violence. Journal of Family Violence, 27, 741–748. doi:10.1007/s10896-012-9463-z.

Smyth B. M., Rodgers B., Allen L. A., & Son V. (2012). Post-separation patterns of children’s overnight stays with each parent: A detailed snapshot. Journal of Family Studies, 18, 202–217. doi:10.5172/jfs.2012.3227.

Smyth B., Caruana C., & Ferro A. (2004). Father-child contact after separation. Profiling five different patterns of care. Family Matters, 67, 20–27 Australian Institute of Family Studies. Retrieved from http://www.aifs.gov.au/institute/pubs/

Statistics Sweden (2012). Gemensam vårdnad. [Joint custody]. Retrieved from http://www.scb.se/Pages/TableAndChart____255870.aspx

Stone G., & McKenry P. (1998). Non-resident father involvement: A test of a mid-range theory. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 159, 313–336. doi:10.1080/00221329809596154.

Straus M. A., Hamby S., Boney-McCoy S., & Sugarman D. (1996). The Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues, 17(3), 283–316. doi:10.1177/019251396017003001.

Straus M. A., Hamby S. L., Finkelhor D., Moore D. W., & Runyan D. (1998). Identification of child maltreatment with the Parent–Child Conflict Tactics Scales: Development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child Abuse & Neglect, 22, 249–270. doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(97)00174-9.

Straus M. (2007). Conflict Tactic Scales. In Encyclopedia of Domestic Violence (pp.190–197), N.A (). Jackson, New York: Routledge.

Swiss L., & Le Bourdais C. (2009). Father-child contact after separation: The influence of living arrangements. Journal of Family Issues, 30, 623–652. doi:10.1177/0192513X08331023.

Trinder L. (2008). Maternal gate closing and gate opening in postdivorce families. Journal of Family Issues, 29, 1298–1324. doi:10.1177/0192513X08315362.

UNCRC (1989). The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Retrieved from: http://www.unicef.org.uk/Documents/Publication-pdfs/UNCRC_PRESS200910web.pdf

Walby S., & Allen J. (2004). Domestic violence, sexual assault and stalking: Findings from the British Crime Survey. In Home Office Research Study 276, London: Home Office Research (). Development and Statistics: Directorate.

Waller M. R., & Swisher R. (2006). Fathers’ risk factors in fragile families: Implications for “healthy” relationships and father involvement. Social Problems, 53, 392–420. Retrieved from: http://www.heinonline.org/.

Whiteside M. F., & Becker B. J. (2000). Parental factors and the young child’s postdivorce adjustment: A meta-analysis with implications for parenting arrangements. Journal of Family Psychology, 14, 5–26. doi:10.1037//0893-3200.14.1.5.

Wolfe D. A., Crooks C. V., Lee V., McIntyre-Smith A., & Jaffe P. G. (2003). The effects of children’s exposure to domestic violence: A meta-analysis and critique. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 6, 171–186. doi:10.1023/A:1024910416164.

Acknowledgement

This study was made possible by grants from the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Forssell, A.M., Cater, Å. Patterns in Child–Father Contact after Parental Separation in a Sample of Child Witnesses to Intimate Partner Violence. J Fam Viol 30, 339–349 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-015-9673-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-015-9673-2