Abstract

Using the most recent version of the Ghana Demographic and Health Survey and employing complementary log-log models, this study examined the causes of both physical and sexual violence among married women in Ghana. Results indicate that wealth and employment status that capture feminist explanations of domestic violence were not significantly related to both physical and sexual violence. Education was however, related to physical violence among Ghanaian women. Women who thought wife beating was justified and those who reported higher levels of control by their husbands had higher odds of experiencing physical and sexual violence. Also, compared to those who had not, women who witnessed family violence in their lives were significantly more likely to have experienced physical and sexual violence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Domestic violence, including marital violence, is a worldwide problem that cuts across culture, class, ethnicity, and age (Dienye and Gbeneol 2009; Kishor and Johnson 2006; Oyeridan and Isiugo-Abanihe 2005; Panda and Agarwal 2005). Globally, it is estimated that over 50 % of women have experienced domestic violence (Kishor and Johnson 2004), and this is more pronounced in Africa. In South Africa, for instance, it is estimated that a woman is killed by her husband or boyfriend every 6 h (see Kimani 2007). In Kenya, almost half of homicide cases in 2007 were related to domestic violence (Kimani 2007). Like other countries in sub-Saharan Africa, domestic violence is a problem in Ghana probably due to the structures of domination and exploitation often peddled through the concept of patriarchy (Ampofo 1993; Ofei-Aboagye 1994; Oyeridan and Isiugo-Abanihe 2005). Of the 5015 cases of domestic violence between January 1999 and December 2002 recorded at the Women and Juvenile Unit (WAJU) of the Ghana Police Service, more than a third was due to wife battering/assault (Amoakohene 2004). A 1998 survey on domestic violence among women in Ghana showed that one in three had been physically abused by a current or most recent partner (Bowman 2003a; Cantalupo et al. 2006; Coker-Appiah and Cusack 1999). In 2010, the National Coordinator of the Domestic Violence and Victims Support Unit in Ghana reported that her outfit recorded about 109,784 cases of violence against women and children (Ghanaweb 2010).

These grim statistics perhaps underestimate the enormity of the problem in Ghana where married women are socialized into believing that marriage confers the ‘right’ of sexual access to husbands no matter how violent. Domestic violence is a violation of fundamental human rights and an obstacle to achieving gender equity, especially in sub-Saharan Africa where patriarchy is dominant (International Center for Research on Women 2009). Also, marital violence has health and psychosocial consequences capable of reversing Ghana’s chances of attaining the United Nations’ Millennium Development Goals, of eradicating violence among women, HIV/AIDS, hunger, and poverty (Abama and Kwaja 2009). While the evidence across sub-Saharan Africa and Ghana in particular, suggests an increase in the incidence and prevalence of domestic and marital violence, the problem has largely been unexplored (Amoakohene 2004; Ofei-Aboagye 1994). In particular, little attention has been given to the socio-cultural factors that influence such violence in Ghana (Amoakohene 2004; Ofei-Aboagye 1994). We fill this void by examining factors associated with domestic violence among married women in Ghana.

The United Nations point to several institutionalized socio-cultural factors that not only evoke, but perpetuate and reinforce violence among women, especially in sub-Saharan Africa including Ghana (UNICEF 2000). These cultural factors, some of which include wife inheritanceFootnote 1 and dowry payments, forced marriages, widowhood rites,Footnote 2 female genital mutilation and ‘trokosi’Footnote 3 (Amoah 2007; Amoakohene 2004; Ampofo 1993) have been unleashed on Ghanaian women including those married, targeted at controlling their sexuality and sexual behaviors. Other factors, deeply rooted in the cultural ethos of the Ghanaian society, and reflected in the socialization of men and women, are the belief in the inherent superiority of men, and the acceptance of violence as a means of resolving conflicts within relationships (Borwankar et al. 2008; Brent et al. 2000; Jejeebhoy and Bott 2003; UNICEF 2000). The gender inequity and power imbalances that characterize most sexual relationships are inextricably linked to the limited educational and training opportunities for women, culminating in their continuous dependence on men. Women in sub-Saharan Africa including those in Ghana have limited access to cash and credit, and to employment opportunities both in the formal and informal sectors (Brent et al. 2000; UNICEF 2000). These render women economically disadvantaged and vulnerable to physical, emotional, and sexual violence. Using data from the 2008 Ghana Demographic and Health Survey, and employing feminist, cultural, and life course perspectives, this study contributes to the literature on domestic and marital violence in sub-Saharan Africa with Ghana as a case study.

Theoretical Perspectives

Theories of domestic violence in Africa range from those that conceptualize violence as a problem of the individual, to that of the family, and the society at large (Black et al. 2010; Dempsey and Day 2010; Dienye and Gbeneol 2009; Ferraro and Johnson 1983; Johnson and Ferraro 2000; McCloskey et al. 2005). For instance, feminist explanations of domestic and marital violence focus on patriarchy, male dominance and control. Central to this framework, is the argument that violence against women is a result of the unequal power relations structurally embedded in a patriarchal system (Black et al. 2010). In Ghana, for instance, women are expected to be subservient to their male partners demonstrated through accepting, and not responding to physical, emotional, and sexual abuse from male partners and by taking care of their husbands in the domestic setting (Amoakohene 2004; Ofei-Aboagye 1994). In one of the pioneering works on domestic violence in Ghana, Ofei-Aboagye (1994) observed that marital violence was mainly a consequence of the subordinate position of women, their passivity, and economic dependence on their male partners. Thus, from the feminist perspective, marital violence can only be addressed as part of a larger process of dealing with gender inequality in Ghana. Consistent with this perspective, some empirical studies (e.g., Bates et al. 2004; Kiss et al. 2012) have found links between socio-economic status and domestic violence among women but the results are mixed. While some studies in South Asia found SES as protective against violence (Babu and Shantanu 2009; Jewkes 2002; Kocacik and Dogan. 2006; Koenig et al. 2003; Mouton et al. 2010; Toufique and Razzaque 2007), others found positive or no evidence (Humphreys 2007; Pandey et al. 2009).

Closely linked to the feminist model are cultural explanations of domestic violence that emphasize tradition, customs, and norms within the African culture as influential in perpetuating such violence. Wife beating and other forms of violence are considered normal and legitimate in most African societies, including Ghana. Ofei-Aboagye (1994) indicated, for instance, that it is not uncommon to find Ghanaian women taking the blame after they have been physically abused to near-fatal point by their husbands. In a related study, Amoakohene (2004) also pointed out that some cultural practices and traditional gender roles in Ghana render women unable to defend their rights even when they are physically and sexually abused. Bowman (2003b) observed that the power imbalances present in traditional African marriages create a unique platform for marital violence. In line with this perspective, past research has found socio-cultural variables such as wife’s justification of violence and husband’s controlling behavior as influential to domestic and marital violence (see Heilman 2010).

Both the life course and family violence perspectives also suggest that experiences and events in early life may influence adult behaviors within intimate relationships not only across an entire lifetime but across generations (Solinas-Saunders 2008). The life-course perspective emphasizes the role of the physical, social, and biological contexts in shaping behaviors across the lifespan (Braveman and Barclay 2009). Consistent with this perspective is the notion that domestic and marital violence is a process and not an event, and that such processes are deeply rooted in a web of familial relationships. Williams (2003) indicated for instance that domestic violence occurs such that each episode may be directly related to past violent episodes or threat of violence, making its study quite complex. Some studies, largely in advanced westernized societies, find that exposure to domestic violence in early years or across the lifespan may be linked to some psychological problems that may create conditions for violence against victims in the future (Becker et al. 2010; Holt et al. 2008; Kessler and Magee 1994). Thus, a major life-course variable considered in this study includes women’s exposure to violence among their parents (whether they saw their fathers beat their own wives). It is expected that women’s exposure to violence in their families of origin would lead to their acceptance or rationalization of violence they suffer from their spouses. Using this perspective, past research has also linked husband’s alcohol use to domestic and marital violence (see Heilman 2010; Kiss et al. 2012; Soler et al. 2000; Toufique and Razzaque 2007). Thus, we explore whether husband’s alcohol use influences marital violence among married women in Ghana.

Method

Participants

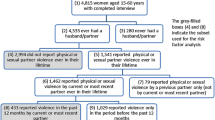

Data for this study were obtained from the most recent version of the Ghana Demographic and Health Survey (GDHS; Ghana Statistical Service 2009). The GDHS is a nationally representative dataset administered by the Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) and Macro International, and the fifth in such surveys of the Global Demographic and Health Surveys Program. GDHS aims at monitoring the population and health conditions of Ghanaians, and is a follow-up on the 1988, 1993, 1998, and 2003 surveys (Ghana Statistical Service 2009). Specifically, detailed information regarding fertility; infant and child mortality; nuptiality; nutritional status of women, infants and children; sexual activity; HIV/AIDS awareness; and other sexually transmitted infections are included in the Demographic and Health Surveys. Recently, the GDHS added high quality data on domestic violence. The domestic violence module provides information on women’s experience of interpersonal violence including acts of physical, sexual, and emotional attacks (Ghana Statistical Service 2009). Questions on domestic violence were asked from ever-married women. The GDHS built specific protections into the questionnaire in accordance with the World Health Organization’s ethical and safety recommendations on domestic violence (see Ghana Statistical Service 2009; World Health Organization 2001). The GDHS used a multi-stage sampling procedure where households were first selected from Enumeration Areas (EAs) and then individuals selected from households. This study is limited to 1835 ever-married women aged 15–45 years who answered questions on domestic violence.

Measures

Two major dependent variables that capture different dimensions of violence against women are employed: Physical violence and sexual violence. The former is a scale measure created from a series of questions that asked respondents if: husband ever pushed shook or threw something at them; husband ever slapped them; husband ever kicked or dragged respondents; husband ever tried to strangle or burn respondents; husband ever threatened or attacked with knife or gun, and if husbands ever twisted respondents’ arms or pull their hair. Sexual violence is also a scale created from two questions that asked women if their husbands ever physically forced sex when not wanted and if husbands ever forced any other sexual acts when not wanted. Response categories for all variables are dichotomous (1 = yes and 0 = no) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was used to create all scales. Reliability coefficients for scales are 0.775 and 0.640 respectively. Positive values on these scales indicate higher physical and sexual violence, while negative values represent lower physical and sexual violence respectively. Diagnostics and exploratory analysis revealed that these scalar measures were not normally distributed, and assumptions of linearity and equal error variance violated when checked against other covariates. This is not very surprising as the distribution of the cases on the two latent constructs were clumped at one end of both scales (physical and sexual abuse were highly skewed). Although power and log transformations were applied, they could not correct the skewness. Under these circumstances, Streiner (2002) advised categorizing or dichotomizing continuous variables and applying non-linear techniques where model assumptions are relaxed. Against these statistical considerations, the variables were categorized with positive values (indicating higher physical or sexual violence) on both scales coded 1, and negative values (indicating lower physical or sexual violence) coded 0. Further diagnostics using “Receiver-Operating Characteristics” (ROC)Footnote 4 analysis indicates that categorizing positive values on the scale as 1 with negative values as 0 was methodologically prudent.

Explanatory variables are categorized into three main blocks: socio-economic, socio-cultural and life course variables. The socio-economic variables include the educational background of women coded (0 = no education, 1 = primary education, 2 = secondary education, and 3 = higher education); employment status of respondents coded (0 = not employed, 1 = employed); and wealth status, a composite index based on the household’s ownership of a number of consumer items including television and a car, flooring material, drinking water, toilet facilities etc. ranged from 0 (poorest) to 4 (richest).

Socio-cultural variables that capture cultural epistemologies of domestic and marital violence are also introduced. These include questions on wife beating and husband’s control and domineering attitudes. The former is an index created from questions that asked women if they consider wife-beating justified if: they go out without telling their husbands, neglects the children, argue with their husbands, refuses to have sex with their husbands, and burns the food. We obtain the latent construct, justification for wife beating (a scale measure) using Principal Component Analysis. Reliability coefficient (Cronbach’s Alpha) for this scale is 0.813. Positive values on the scale indicate higher levels of justification for wife beating, while negative values indicate otherwise. Husband’s control or domineering attitudes was also created using PCA from variables that asked women if: their husbands get jealous on seeing them talk with other men, husband accuses respondents of unfaithfulness, husband does not permit wife to meet her girlfriends, husband tries to limit respondent’s contact with family, husband insists on knowing where respondent is, husband doesn’t trust respondent with money, husband refuses or denies sex with the respondent. Reliability coefficient (Cronbach’s Alpha) is 0.690. Positive values on the scale indicate higher levels of control by husbands of respondents, while negative values indicate lower levels of control.

Two other variables are introduced as life-course and family violence variables. These include if ‘respondent’s father ever beat her mother’ coded (0 = no, 1 = yes, 2 = don’t know) and if respondent’s husband drinks alcohol also coded (0 = no, 1 = yes). Ethnicity coded (0 = Akan, 1 = Ga/Adangbe, 2 = Ewe, 3 = Northern languages, 4 = other languages), religion coded (0 = Christians, 1 = Muslims, 2 = Traditional, 3 = no religion); rural/urban residence (0 = urban, 1 = rural); region of residence (0 = Greater Accra, 1 = Central, 2 = Western, 3 = Volta, 4 = Eastern, 5 = Ashanti, 6 = Brong Ahafo, 7 = Northern, 8 = Upper East, 9 = Upper West) and age of respondents were all used as control variables.

Data Analysis

The dependent variables used in this study are dichotomous, but as shown in Table 1, cases are unevenly distributed, meaning that using a probit or logit link function that assumed a symmetrical distribution could produce biased parameter estimates (Gyimah et al. 2010; Tenkorang and Owusu 2010). As a result, we chose the complementary log-log function, which is better suited for asymmetrical distributions. The standard complementary log-log models are built on the assumption of independence of observations, but the GDHS has a hierarchical structure with participants nested within survey clusters, which could potentially bias the standard errors. To control for this dependence, we employed random effects models that enabled us to estimate the magnitude and significance of clustering (Guo and Zhao 2000; Pebley et al. 1996; Raudenbush and Bryk 2002). The extent of clustering in our models was measured using intra-class correlations. For standard complementary log-log models, this was calculated as the ratio of the variance at the cluster level to the sum of the variances at the individual and cluster levels. That is:

\( \rho =\raisebox{1ex}{${\sigma}_u{}^2$}\!\left/ \!\raisebox{-1ex}{${\sigma}_u{}^2$}\right.+\frac{\pi^2}{6} \) where σ u 2 is the cluster level variance and \( \frac{\pi^2}{6} \) the variance at level 1 (individual level) which is that of the standard logistic regression (Gyimah et al. 2010; Tenkorang and Owusu 2010). The GLLAMM program available in STATA was used to build all models.

Results

Descriptive results in Table 1 indicate higher levels of physical violence (18.4 %) compared to sexual violence (5.1 %) among married women in Ghana. The average age of women in the sample is 32 years. Majority of women live in the rural areas and are Christians. While about 42 % of married women had secondary education, quite a substantial percentage also had no education (31.8 %). The negative median scores for ‘justification for wife beating’ and ‘husband’s control over wife’ indicate that majority of married women in Ghana do not endorse or justify wife beating, and are against husband’s controlling or domineering attitudes. About 13 % of married women reported having witnessed their father beat their mother. Also, approximately 38 % of married women reported their husbands drank alcohol, compared to 62 % who did not.

Table 2 shows bivariate relationships of physical and sexual abuse and selected covariates. Results indicate significant relationships between education and physical abuse, but not sexual abuse. Compared to women with no education, those with higher education were less likely to report higher levels of physical abuse. Cultural variables are significantly related to both physical and sexual abuse among married women in Ghana. Higher levels of control by husbands are significantly related to higher levels of physical and sexual abuse. Similarly, endorsing or justifying wife beating was positively and significantly associated with physical and sexual abuse. Life-course variables are significantly related to both physical and sexual abuse at the bivariate level. Married women who saw their fathers beat their wives were significantly more likely to experience higher levels of physical and sexual violence, compared with those who did not. Also, women who indicated that their husbands drank alcohol were significantly more likely to report high levels of abuse. Regarding control variables, we find Ewes and women with no religion as significantly more likely to experience higher levels of sexual abuse. Compared with those in the Greater Accra region, married women in the western region of Ghana were significantly less likely to experience higher levels of physical violence. Those in the Upper West region were however significantly more likely to experience higher levels of physical violence.

Multivariate results are presented in both Tables 3 and 4. Three models are presented each for physical and sexual abuse. The first model examines the effects of socio-economic variables; the second model adds cultural variables; and the third life course and family violence variables. All three models control for socio-demographic variables such as age, place of residence, region of residence, ethnicity, and religion. Except education, socioeconomic variables were not significantly related to physical and sexual violence. Consistent with the bivariate results, we find that women with higher education were significantly less likely to have experienced high levels of physical violence, compared to those with no education. Cultural variables are also significantly related to both physical and sexual abuse. Women who endorsed wife beating and thought such attitudes were justified and legitimate, were about 14 % and 26 % more likely to experience both physical and sexual abuse respectively (see Model 3 of Tables 3 and 4). Similarly, women who reported higher levels of control by husbands were 60 % and 85 % more likely to have experienced physical and sexual abuse respectively (see Model 3 of Tables 3 and 4). Life course variables are strongly related to both physical and sexual abuse among married women in Ghana. Women who reported that they saw their fathers beat their wives were 69 % and 2.7 times more likely to have experienced both physical and sexual abuse. Similarly, women whose husbands drank alcohol were about 2.5 times and 2.9 times more likely to experience physical and sexual violence respectively. Some control variables were significantly associated to physical but not sexual abuse. For instance, compared to those in urban areas, married women in rural areas were significantly less likely to experience physical violence. Those in the Northern and Upper West regions of Ghana were significantly more likely to experience high levels of domestic violence compared to women in the Greater Accra region. Intra-class correlations estimated for all models are not significant. There are two interpretations to this. First, that the level of clustering within the data is not significant enough to bias parameter estimates, and second that individual level variables are enough to explain physical and sexual abuse among married women in Ghana.

Discussion

Domestic and marital violence is a global problem that cuts across age, class, ethnic, and religious groups. Although women can be abusive in their relationships with men, the evidence indicates that women are mostly at the receiving end, as they suffer most cases of abuse (Kurz 1997). As is the case elsewhere, domestic and marital violence is on the increase and has gained wide currency among Ghanaian women. Unfortunately, however, we do not fully understand the factors that predispose women to such violence, especially in Ghana where the literature is woefully scant in this area. This paper fills an important research gap by identifying socio-economic, cultural, and life course factors that affect two major dimensions of domestic violence: physical and sexual violence. Results indicate that wealth, occupation, age, and ethnicity are not significant predictors of both physical and sexual violence among married women in Ghana. These results are testament to earlier observations that domestic and marital violence may not be peculiar to specific demographic and economic groups. While wealth and employment may encourage economic independence and empower women as postulated by feminist epistemologies, such independence may not directly translate into helping women avoid conflicts and violence within marriages. In fact, avoiding violence within marriage may require some relevant life-skills that formal education may rather provide. Jewkes (2002) has noted for instance, that education confers on individuals social empowerment, self-confidence, and the ability to use information and resources to one’s advantage. It is therefore not surprising that highly educated women were rather less likely to experience higher levels of physical violence compared to women with no education. The independent effects of education on domestic violence have been documented elsewhere (Babu and Shantanu 2009; Flood and Pease 2009; Jewkes 2002; Kocacik and Dogan 2006; Koenig et al. 2003).

Cultural explanations of domestic violence have referred to some existing norms and traditional gender roles that create platforms for violence against married women in sub-Saharan Africa and Ghana. African and Ghanaian culture demand that women not only be submissive to their husbands, but also be respectful, dutiful, and serviceable to the extent that revolting against or challenging abuse may be interpreted as attempting to subvert the authority of the man (Amoakohene 2004). Such cultural norms have projected African societies as inherently patriarchal, ones that condone male superiority, the basis for which wife beating and other forms of violence may sometimes be legitimized. Our results are consistent with the assumptions espoused by cultural models of domestic violence. The finding that husband’s control of wives’ activities was significantly related to both physical and sexual violence independent of other variables, demonstrate how the power imbalances characterizing marital relationships and resulting from the cultural make of the Ghanaian society influences violence among married women. Also, wife beating, though is detrimental to women’s health have often been interpreted as not only a demonstration of a husband’s love for his wife, but also a symbol of his authority (Jejeebhoy 1998). Thus, women who consider wife beating as legitimate may have internalized such cultural norms and would seek to create conditions that attract such acts. This may explain why women who thought wife beating was justified had higher odds of experiencing physical and sexual violence.

Life course theories link previous or past experiences to recent or current occurrences. Applying this perspective to domestic and marital violence would suggest that violence experienced by women may not be independent of similar experiences in the past. Consistent with the life course perspective, we find that women who witnessed their fathers beat their respective wives were significantly more likely to experience higher levels of both physical and sexual violence, compared to those who did not. While it is difficult to establish direct causal connections, it is clear that children of battered women may also be affected in later years. Williams (2003) observed that battering one’s wife or the mother of one’s child may not only be an assault on the couple relationship but also the parenting relationship. In this light, some studies have found that individuals exposed to family violence earlier, maintain and replicate patterns of such violence and abuse in later years (see Giles-Sims 1985). It is possible that women who witnessed their fathers beat their wives may have learned and imported violent attitudes into their marital unions attracting violent response from their spouses. A bivariate analysis of witnessing domestic violence between parents and justification for wife beating (not shown) indicate that women who witnessed domestic violence among parents endorsed or justified wife beating compared to those who did not. This means exposure to previous violence, especially when unpunished may be internalized, legitimized, and treated as “normal” by women even in future and subsequent relationships. Thus, in attempting to find solutions to domestic violence among married women in Ghana, it is important we consider the life histories of women.

Our finding of a strong positive relationship between husband’s alcohol/drinking behaviors and marital violence (both physical and sexual abuse) is supported by studies elsewhere (Kiss et al. 2012; Oladepo et al. 2011; Pandey et al. 2009; Soler et al. 2000; Wilt and Olson 1996). Given data limitations, it is difficult to determine the independent role that husband’s alcohol use play in physical and sexual violence. It is possible however, that alcohol use could either influence or instigate violent behaviors. In fact, Pandey et al. (2009) observed that alcohol use may sometimes provide socially acceptable reasons for husbands beating their wives. Findings of higher levels of physical violence among women in the Northern and Upper West regions, compared to those in Greater Accra are consistent with research results that indicate that torture, beatings, and destruction of spousal property are among the common types of violence experienced by women in the Northern regions of Ghana (Ghana News Agency [GNA], 2005). Our findings indicate that married women in rural areas were significantly less likely to experience physical violence. However, it was expected that marital violence will be higher in rural areas compared to the urban areas of Ghana due mainly to lack of contact with modern values and the entrenchment of traditional patriarchal value systems that usually support abuse of women. Also, women in rural areas tend to be less socially empowered (due to low levels of education) to even notice and report cases of abuse (Pruitt 2008). It is thus possible that rural women may be under-reporting cases of physical abuse compared to those in urban areas of Ghana.

A number of policy considerations emerge from this study. First, it is important that policy makers in Ghana create educational opportunities (including formal education) that not only empower women and enhance their independence and assertiveness, but also equip them with the skills to negotiate conflicts within homes. Providing women with such opportunities could also help in correcting the power imbalances that characterize marital unions and dealing with the cultural barriers that constrain women’s ability to seek equality in their relationships. Our findings suggest that domestic violence in subsequent years is associated with family violence in previous years. Thus, interventions that target stages at which victims of domestic violence were first exposed may help reduce this problem in later years.

At the moment, Ghanaian laws on domestic violence (Domestic Violence Act, 2007) are silent on marital rape. We believe that the paucity of research in this area is strongly reflected in the deficiencies of the Ghana Domestic Violence Act (2007). Findings of this study will not only create awareness among policy makers and civil society, but also influence policy directions towards curbing the menace in Ghana.

Despite the policy relevance of our findings, there are some shortcomings worth acknowledging. The use of cross-sectional data limits the interpretation of our findings. Although inferences can be made about associations between dependent and independent variables, causal inferences cannot be drawn. Some scholars have questioned the reliability of surveys based on self-reports, especially when they border on sensitive issues like violence within marriages. It is thus possible that physical and sexual violence will be under-reported especially among married couples given the stigma and other related consequences attached to reporting such incidence in most African societies. This notwithstanding, the attempt by GDHS to include a module on domestic and marital violence, and the circumstances surrounding such incidence is useful given the general lack of large scale quantitative studies on this subject, especially for Ghana. It is recommended that future data collection efforts focus and expand on the role that culture and patriarchy play in perpetuating marital violence in Ghana. Given the relevance of life course variables in this study, it is also recommended that future data collection efforts focus on variables that capture the life course trajectories and linked lives of respondents.

Notes

A practice in which a woman becomes the automatic wife of the brother of her late husband

Trokosi’ comes from two words, ‘Tro’ meaning God and ‘Kosi’ translated as virgin, slave or wife. The practice demands that women, in particular, young girls be given as slaves to priests of specific shrines to appease the gods or spirits of crimes perpetrated by some family members (see Amoah 2007).

A technique that helps in the determination of an “ideal” cut-off value based on the trade-offs between sensitivity and specificity. In ideal situations the desired cut-off value produces the highest sensitivity and specificity.

References

Abama, E., & Kwaja, C. M. (2009). Violence against women in Nigeria: How the millennium development goals addresses the challenge. Journal of Pan African Studies, 3, 23–34.

Amoah, J. (2007). The world on her shoulders: the rights of the girl-child in the context of culture and identity. Essex Human Rights Review, 4, 1–23.

Amoakohene, M. I. (2004). Violence against women in Ghana: a look at women’s perceptions and review of policy and social responses. Social Science and Medicine, 59, 2373–2385.

Ampofo, A. A. (1993). Controlling and punishing women: violence against Ghanaian women. Review of African Political Economy, 56, 102–111.

Babu, B. V., & Shantanu, K. J. (2009). Domestic violence against women in eastern India: a population-based study on prevalence and related issues. BMC Public Health, 9, 129–144.

Bates, L. M., Schuler, S. R., Islam, F., & Islam, K. (2004). Socio-economic factors and processes associated with domestic violence in rural Bangladesh. International Family Planning Perspectives, 30, 190–199.

Becker, K. D., Stuewig, J., & McCloskey, L. A. (2010). Traumatic stress symptoms of women exposed to different forms childhood victimization and intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25, 1699–1715.

Black, B. M., Weisz, A. N., & Bennett, L. W. (2010). Graduating social work students’ perspectives on domestic violence. Journal of Women and Social Work, 25, 173–184.

Borwankar, R., Diallo, R., & Sommerfelt, A. E. (2008). Gender-based violence in sub-Saharan Africa: A review of Demographic and Health Survey findings and their use in National Planning. Washington: USAID/AFR/SD and Africa’s Health in 2010/AED.

Bowman, C. G. (2003a). Domestic violence: Does the African context demand a different approach? International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 26, 473–491.

Bowman, C. G. (2003b). Theories of domestic violence in the African context. Journal of Gender, Social Policy & the Law, 11, 847–863.

Braveman, P., & Barclay, C. (2009). Health disparities beginning in childhood: a life-course perspective. Pediatrics, 124, S163–S174.

Brent, W., Blanc, A. K., & Gage, A. J. (2000). Who decides? Women’s status and negotiations of sex in Uganda. Culture, Health and Sexuality, 2, 303–322.

Cantalupo, N., Martin, L. V., Pak, K., & Shin, S. (2006). Domestic violence in Ghana: the open secret. The Georgetown Journal of Gender and the Law, 2, 531–597.

Coker-Appiah, D., & Cusack, K. (Eds.). (1999). Breaking the silence and challenging the myths of violence against women and children in Ghana: Report on a national study of violence. Accra: Gender Studies & Human Rights Documentation Centre.

Dempsey, B., & Day, A. (2010). The identification of implicit in domestic violence perpetrators. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 55, 416–429.

Dienye, P. O., & Gbeneol, P. K. (2009). Domestic violence against men in primary care in Nigeria. American Journal of Men’s Health, 3, 333–339.

Domestic Violence Act (2007). Act 732. Retrieved from http://www.parliament.gh/assets/file/Acts/Domestic%20Violence%20%20Act%20732.pdf.

Ferraro, K. J., & Johnson, J. M. (1983). How women experience battering: the process of victimization. Social Problems, 30, 325–339.

Flood, M., & Pease, B. (2009). Factors influencing attitudes to violence against women. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 10, 125–142.

Ghana News Agency (2005). Northern region records high incidence of violence against women.

Ghana Statistical Service. (2009). Ghana Demographic and Health Survey 2008. Accra, Ghana: GSS, GHS, and ICF Macro. Retrieved from http://www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pdf/FR221/FR221[13Aug2012].pdf

Ghanaweb. (2010). 109,784 cases of domestic violence recorded. Retrieved from http://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/artikel.php?ID=183316

Giles-Sims, J. (1985). A longitudinal study of battered children of battered wives. Family Relations, 34, 205–210.

Guo, G., & Zhao, H. (2000). Multilevel modeling for binary data. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 441–462.

Gyimah, S. O., Tenkorang, E. Y., Takyi, B. K., Adjei, J., & Fosu, G. (2010). Religion, HIV/AIDS and sexual risk-taking among men in Ghana. Journal of Biosocial science, 42, 531–547.

Heilman, B. P. (2010). A life-course perspective of Intimate Partner Violence in India: What picture does the NFHS-3 paint? Master’s thesis). Retrieved from Tuffts University Digital Library http://hdl.handle.net/10427/57567

Holt, S., Buckley, H., & Whelan, S. (2008). The impact of exposure to domestic violence on children and young people: a review of the literature. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32, 797–810.

Humphreys, C. (2007). A health inequalities perspective on violence against women. Health and Social Care in the Community, 15, 120–127.

International Center for Research on Women (2009). Intimate Partner Violence: High cost to households and communities. A publication of UNFPA. Retrieved from http://www.icrw.org/files/publications/Intimate-Partner-Violence-High-Cost-to-Households-and-Communities.pdf

Jejeebhoy, S. J. (1998). Wife-beating in rural India: a husband’s right? Evidence from survey data. Economic and Political Weekly, 33, 855–862.

Jejeebhoy, S. J., & Bott, S. (2003). Non-consensual sexual experiences of young people: A review of the evidence from developing countries. Regional Working Papers, No. 13.Population Council, New Delhi, India.

Jewkes, R. (2002). Intimate partner violence: causes and prevention. Lancet, 359, 1423–1429.

Johnson, M. P., & Ferraro, K. J. (2000). Research on domestic violence in the 1990s: making distinctions. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 948–963.

Kessler, R. C., & Magee, W. J. (1994). Childhood family violence and adult recurrent depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 35, 13–27.

Kimani, M. (2007). Taking on violence against women in Africa: international norms, local activism start to alter laws, attitudes. Africa Renewal, 21, 4.

Kishor, S., & Johnson, K. (2004). Profiling domestic violence - a multi country study. Calverton: ORC Macro.

Kishor, S., & Johnson, K. (2006). Reproductive health and domestic violence: Are the poorest women uniquely disadvantaged? Demography, 43, 293–307.

Kiss, L., Schraiber, L. B., Heise, L., Zimmerman, C., Gouveia, N., & Watts, C. (2012). Gender-based violence and socio-economic inequalities: Does living in more deprived neighborhoods increase women’s risk of intimate partner violence? Social Science & Medicine, 74, 1172–1179.

Kocacik, F., & Dogan, O. (2006). Domestic violence against women in Sivas, Turkey: survey study. Croatian Medical Journal, 47, 742–749.

Koenig, M. A., Ahmed, S., Hossain, M. B., & Mozumder, K. A. (2003). Women’s Status and domestic violence in Bangladesh: individual and community-level effects. Demography, 40, 269–288.

Kurz, D. (1997). Physical Assaults by male partners: A major social problem. In M. R. Walsh (Ed.), Women, men, & gender: Ongoing debates (pp. 222–246). New Haven: Yale University Press.

McCloskey, L. A., Williams, C., & Larsen, U. (2005). Gender inequality and intimate partner violence among women in Moshi, Tanzania. International Family Planning Perspectives, 31, 124–130.

Mouton, C. P., Rodabough, R. J., Rovi, S. L. D., Brzyski, R. G., & Katerndahl, D. A. (2010). Psychosocial effects of physical and verbal abuse in postmenopausal women. Annual Family Medicine, 8, 206–213.

Ofei-Aboagye, R. O. (1994). Altering the strands of the fabric: a preliminary look at domestic violence in Ghana. Feminism and the Law, 19, 924–938.

Oladepo, O., Yusuf, O. B., & Arulogun, O. S. (2011). Factors influencing gender based violence among men and women in selected states in Nigeria. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 15, 78–86.

Oyeridan, K. A., & Isiugo-Abanihe, U. C. (2005). Perceptions of Nigerian women on domestic violence: evidence from 2003 Nigeria demographic and health survey. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 9, 38–53.

Panda, P., & Agarwal, B. (2005). Marital violence, human development and women’s property status in India. World Development, 33, 823–850.

Pandey, G. K., Dutt, D., & Banerjee, B. (2009). Partner and relationship factors in domestic violence: perspectives of women from a slum in Calcutta, India. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24, 1175–1191.

Pebley, A. R., Goldman, N., & Rodriguez, G. (1996). Prenatal and delivery care childhood immunization in Guatemala: Do family and community matter? Demography, 33, 231–247.

Pruitt, L. R. (2008). Place matters: domestic violence and rural difference. Wisconsin Journal of Law, Gender & Society, 23, 345–416.

Raudenbush, S. W., & Bryk, A. S. (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

Soler, H., Vinayak, P., & Quadagno, D. (2000). Biosocial aspects of domestic violence. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 25, 721–739.

Solinas-Saunders, M. (2008). Male intimate partner abuse: Drawing upon three theoretical perspectives. (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Pittsburgh, School of Arts and Sciences.

Streiner, D. L. (2002). Breaking up is hard to do: the heartbreak of dichotomizing continuous data. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 47, 262–266.

Tenkorang, E. Y., & Owusu, G. (2010). Correlates of HIV/AIDS testing in Ghana: some evidence from the demographic and health surveys. AIDS Care, 22, 296–307.

Toufique, M. M. K. & Razzaque, M. A. (2007). Domestic violence against women: Its determinants and implications for gender resource allocation. (Research paper No. 2007/80). United Nations University: World Institute for Development Economics Research, UNU-WIDER.

UNICEF. (2000). Domestic violence against women and girls. Innocenti Digest, 6. Retrieved from http://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/digest6e.pdf

Williams, L. M. (2003). Understanding child abuse and violence against women: a life course perspective. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 18, 441–451.

Wilt, S., & Olson, S. (1996). Prevalence of domestic violence in the United States. JAMWA, 51, 77–82.

World Health Organization. (2001). Putting women first: Ethical and safety recommendations for research on domestic violence against women. Geneva: Department of Gender and Women’s Health, WHO.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tenkorang, E.Y., Owusu, A.Y., Yeboah, E.H. et al. Factors Influencing Domestic and Marital Violence against Women in Ghana. J Fam Viol 28, 771–781 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-013-9543-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-013-9543-8