Abstract

Given the prevalence and impact of intimate partner violence (IPV) in both community and therapeutic settings, it is vital that the varying typologies of IPV be identified and treated accordingly. The present study sought to evaluate the efficacy of a screening instrument designed to differentiate between characterologically violent, situationally violent, and distressed non-violent couples; focus was placed on identifying situationally violent couples so that they could be invited to participate in a conjoint pyschoeducational workshop. Couples from two samples were assessed to achieve this goal. Situationally violent couples (N = 115) from Sample 1 were screened into the study via a phone interview and participated in an in-home assessment, which assessed self-reported relationship violence. These couples were compared to a previously collected sample (Sample 2; Jacobsen et al. 1994) of characterologically violent, distressed non-violent, and situationally violent couples. The main hypotheses stated that couples from Sample 1 would report less severe relationship violence than characterlogically violent couples from Sample 2, and would report greater amounts of low-level violence than distressed non-violent couples from Sample 2. Additionally, similar rates of both self-reported violence would be seen for situationally violent couples from Samples 1 and 2. Multivariate analyses supported this with the exception that situationally violent couples from Sample 1 did not differ significantly across all domains from distressed non-violent couples in Sample 2. Implications for the screening instrument’s utility in clinical and research settings are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Research has shown intimate partner violence (IPV) to be more complex than originally thought, revealing sub-groups of batterers (Holtzworth-Munroe & Stuart, 1994; Gottman et al. 1995; Tweed & Dutton, 1998) and subtypes of IPV (Johnson, 2006; Jacobson & Gottman 1998). Johnson and Ferraro (2000) distinguished between two types of IPV: situational and characterological. Characterological is defined as IPV in which the perpetrator uses severe violence as a means of inducing fear and controlling the victim. Situational is mutual, low-level violence (i.e. pushing or grabbing) perpetrated by both partners as a means of conflict management. Straus and Gelles (1986) found that 50% of physically aggressive couples exhibit low-levels of mutual violence that is situational in nature.

Traditional IPV treatment focuses on male perpetrators/female survivors and follows the standard Duluth model, which operates under the assumption that all violence is patriarchal (Pence & Paymar, 1993). Researchers have argued that this standard treatment ignores typology research and may be ineffective with situational violence (Stith et al. 2003; Babcock, Green & Robie, 2004). As a result, researchers and clinicians have developed new models for IPV treatment, including conjoint couples’ therapy. Thus far, this type of intervention has been safely and effectively implemented with situationally violent couples without increasing levels of violence (Stith et al. 2004; Simpson et al. 2008). It is important to note, however, that couples experiencing characterological violence should not be treated conjointly due to the danger of perpetrator retribution for victim disclosures during therapy (Holtzworth-Munroe, 2001). Therefore, it is vital to distinguish characterological from situational violence.

In the current study, we attempted to recruit and enroll situationally violent couples into a psycho-educational, conjoint workshop aimed at reducing IPV and fostering healthy relationships (see Bradley et al. 2011 for workshop description and effects). To differentiate between couples who experience characterological versus situational violence (versus no violence at all), a screening instrument was developed. The goal of this paper is to discuss the efficacy of this screening instrument to accurately identify situationally violent couples, and distinguish them from both characterologically violent and non-violent couples. The efficacy was determined by comparing screened-in, situationally violent couples (from Sample 1) to a previously collected sample (Sample 2: Jacobson et al. 1994) consisting of couples with varying IPV typologies.

Intimate Partner Violence Typologies

Although research has uncovered varying types of IPV perpetrators (e.g., Holtzworth-Munroe & Stuart, 1994; Gottman et al., 1995; Tweed & Dutton, 1998), little research has focused on overarching typologies of IPV (Carlson & Jones, 2010). Johnson (1995), Johnson and Ferraro (2000), and Kelly and Johnson (2008) have created a body of work that outlines the distinctions seen in various types of IPV and found four distinct types of IPV: (1) characterological violence, (2) violent resistance, (3) situational violence, and (4) separation-instigated violence (for the purposes of this paper, only characterological and situational violence will be discussed; for full review on typologies, see Kelly & Johnson, 2008).

Characterological violence follows the Pence and Paymar (1993) Power and Control Wheel pattern, where severe emotional and physical violence are used to dominate, control, and manipulate a romantic partner. Characterlogically violent perpetrators are likely to endorse and express violence-supporting attitudes (Leone et al. 2007) and display antisocial or borderline personality traits (Kelly & Johnson, 2008).

Situational violence is physical aggression between partners consisting of low-level violence (e.g. pushing, shoving grabbing, etc.) that is reciprocal in nature and occurs at a low frequency (Johnson & Leone, 2005). The psychological abuse is similar to the psychological abuse seen in characterological violence, but it occurs less frequently and is absent of controlling and dominating behaviors (Kelly & Johnson, 2008). Situationally violent men do not differ from nonviolent men in terms of borderline and antisocial traits (Kelly & Johnson, 2008; Costa & Babcock, 2008). Johnson (2006) found that this type accounted for 89% of violence found in a community sample, with the other 11% being classified as characterological. Conversely, situational violence accounted for only 29% of those individuals going through the justice system (Kelly & Johnson, 2008), suggesting that public intervention by law enforcement may be more likely in response to characterological violence. Situational violence is thought to occur as a result of unmanageable conflict that escalates and turns into physical aggression. Jacobson and Gottman (1998) found a “low-level violence” group in their study on couples experiencing IPV; this group shared characteristics of situational violence. They hypothesized that violence would escalate within this group. Instead, they found that this low-level group remained stable over time, never escalating to severe-levels or characterological violence.

Treatment for Situational IPV

Stith et al. (2004) argued that, due to the heterogeneity of IPV, multiple treatment options are needed that address the type of IPV exhibited by the couple. Most standard IPV treatments are designed to treat male perpetrators (Pence & Paymar, 1993). Multiple studies have demonstrated that traditional psycho-educational programs that are currently available are not effective for all forms of IPV (Babcock et al. 2004; Stith et al. 2004; Stith et al., 2003). This lack of efficacy can be explained by Johnson’s (2000) typologies and the understanding that various forms of IPV exist and should be treated differently. In the case of situational violence both partners are perpetrators, thus treating the male partner alone would be ineffective.

With this in mind, some have suggested that conjoint treatment may be more effective for situationally violent couples. The opportunities given to these couples in conjoint sessions allow for correction of conflict management issues, support for each partner in learning problem-solving techniques, and therapy plans that can be tailored to meet the needs of these individuals (Harris, 2006). Although several conjoint treatment options have been developed, few have been empirically tested/validated (Babcock & La Taillade, 2000; Stith et al., 2003). Treatments that have been tested have shown conjoint treatment to be safely implemented and effective in improving relationship quality (Bradley et al., 2011), as well as reducing relationship violence/aggression and rates of violence recidivism (Stith et al., 2004; Simpson et al., 2008).

Identification of IPV Typologies

Based on distinctions between IPV typologies that are now evident, it is vital that clinicians and researchers are able to distinguish situationally violent couples from couples experiencing other forms of IPV so that we may improve knowledge of IPV typologies and associated outcomes, and identify appropriate treatment methods. Although screening instruments have been widely utilized in health care settings (Rabin et al. 2009) most ignore Johnson’s (2000) typologies and do not capture instances of situational violence specifically; rather, most identification tools simply lump this form of violence into a general IPV category.

Due to the fact that violence is highly prevalent (as high as 74%) among couples seeking relationship/family therapy (Simpson et al., 2007; Todahl et al. 2008; Bradford, 2010; Bogard & Mederos, 1999; O’Leary et al. 1992; Cascardi et al. 1992; Ehrensaft & Vivian, 1996), many have advocated for universal screening of clients seeking therapy to minimize risk and optimize safety and efficacy of treatment (Carlson & Jones, 2010; Bradford, 2010; Todahl et al., 2008). Although promising techniques have been developed and current clinical ethics encourage the screening of all clients for potential IPV, research has found that many clinicians do not employ universal screening techniques (Todahl et al., 2008; Schacht et al. 2009; Todahl & Walters 2009a, 2009b). This underscores the need to develop effective screening techniques that enable discernment of IPV typologies in order to better determine proper treatment options and efficacy.

Even with the advancement of screening techniques, many clients choose not to disclose violence for numerous reasons, ranging from denial to therapist competency during screening (Jory, 2004; Todahl et al., 2008). In response to this, Jory (2004) developed the Intimate Justice Scale (IJS) for clinical assessment of IPV. The IJS does not ask participants to self-report on specific violent behaviors, but instead taps relationship dynamics (i.e. motivation, choice, beliefs and impact on respondent) that are associated with IPV. The theoretical basis behind this was that, by measuring the associated behaviors rather than IPV itself, disclosure of the violence by the client would increase while still providing a barometer as to the severity of IPV. Although highly reliable with the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS; Straus, 1979), Jory (2004) noted that the IJS is intended to be part of a multi-modal assessment and is not a substitute for more traditional measures that inquire about severity or frequency of IPV. Although the IJS shows great clinical promise, its power to correctly differentiate IPV typologies has not yet been evaluated.

The Current Study

The primary goal of this work was to evaluate the efficacy of a screening instrument developed to identify situationally violent couples, characterologically violent couples, and non-violent couples in order to determine suitability for conjoint treatment. Couples interested in the program completed a telephone screen consisting of the following: (1) IPV violence assessment (assessing frequency and severity of IPV over the past 12 months), (2) the IJS,Footnote 1 (3) a drug/alcohol screen, and (4) an assessment for Antisocial Personality Disorder. To be classified as situationally violent, couples had to exhibit low-levels of relationship violence by either directly reporting such violence and/or scoring within the situational violence range on the IJS.

To determine the efficacy of the screening instrument, we utilized assessed couples from Sample 1, capturing self-reported IPV and legal data. Using this data, we compared couples identified as situationally violent via the screening tool (SV1) to a previously collected sample (Sample 2) of characterologically violent (CV), situationally violent (SV2), and distressed non-violent (DNV) couples. Sample 2 was first described in Jacobson et al. (1994) and is also described elsewhere (e.g. Gottman et al., 1995; Coan et al. 1997; Jacobson & Gottman 1998; Waltz et al. 2000).

The following hypotheses were tested to determine the success of the screening instrument to identify situationally violent couples from all others: (1) SV1 couples would differ from both CV and DNV couples in terms of self-reported IPV, but would not differ from SV2 couples; (2) SV1 couples who did not directly report IPV but were screened-in based on IJS scores would not differ in self-reported IPV levels when compared to couples who reported IPV; and (3) examination of legal data would confirm the screening instrument’s efficacy by showing few to no couples being involved with the justice system over IPV incidents.

Sample 1

Method

Participants

Study procedures were approved by the Western IRB to ensure compliance with ethical research standards. Couples were recruited from Western Washington State via community-based organizations, government agencies, and radio/online advertisements.

Low-income distressed couples who were interested in participating in a research study on conflictual romantic relationships were instructed to contact study personnel via phone or email. Research staff followed-up with each inquiry to screen these couples for eligibility.Footnote 2

The Screening Instrument and Screening Procedures Footnote 3

Phone interviewers trained in crisis management assessed eligibility criteria with each individual member of the couple separately. Interviewing couples via telephone was done to allow for a relationship to be established between the interviewer and participant while providing a feeling of anonymity to the caller. Additionally, phone screening allowed both parties to ask clarifying questions that provided further understanding regarding the context and frequency of IPV and any subsequent disclosures that may not be captured through self-report measures.

Once consent was obtained from both partners, women participated in the screening first due to the nature of characterological violence, which typically has more female victims (Johnson, 2000). In addition to basic demographic information, callers participated in a warm-up questionnaire about the quality of their relationship (Marital Adjustment Test; Locke & Wallace, 1959) that was administered to establish rapport prior to asking more sensitive questions.

After the warm-up questionnaire, all participants completed the following items: (1) a modified version of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS-2; Straus et al. 1996), (2) AUDIT questionnaire for alcohol abuse (Babor et al. 1992), (3) DAST-10 to assess drug use (Skinner, 1982), and (4) Antisocial Personality Disorder (Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Disorders (SCID-II; First et al. 1995)

In order to be eligible, subjects had to endorse low-levels of violence (situational violence), report no severe physical or psychological IPV (characterological violence), and screen negative for substance abuse issues and persistent antisocial behavior. All three of the latter constructs have been consistently linked to characterological violence (Costa & Babcock, 2008; Ross & Babcock, 2009; Johnson, 2000; Holtzworth-Munroe & Stuart, 1994).

Individuals often underreport instances of violence when directly asked (Chan, 2011; Archer, 2000; Jory, 2004; Dutton & Nicholls, 2005). To capture those who may have been underreporting IPV, the IJS (Jory, 2004) was included in the screening interview.Footnote 4 The IJS consists of 15-items that inquire about relationship behaviors found to be highly correlated with incidence of IPV. The IJS has been found to be highly reliable (α = .98) and has excellent criteria validity with the CTS and Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS; Spanier 1976). Scores between 30 and 45, out of 75 possible points, indicate a high likelihood of situational violence, whereas scores greater than 45 indicate the potential for more severe characterological violence (Jory, 2004).

Regardless of IJS scores, all participants completed the revised CTS-2. If no situationally or characterologically violent behaviors were reported on the revised CTS-2, an IJS score of 30–45 was used to denote situational violence and thus study eligibility. Those who scored above 45 were considered ineligible due to high potential for characterological violence, even if no characterologically violent behaviors were endorsed on the revised CTS-2. A total of 63 couples were screened into the study based solely on IJS scores.

In total, 1,699 couples were interviewed for possible enrollment into the study. Of this total, 128 couples were deemed eligible and 1,571 were screened out. Of those screened out, 4% percent (n = 63) were screened out for characterological violence and 4.9% (n = 77) for lack of situational violence. Of the 128 eligible couples, 115 participated in self-report assessments (for further details/demographics of this sample, please see Bradley et al., 2011).

Assessment Procedures

Following completion of the screener, couples were mailed a self-report questionnaire packet that was collected at an in-home assessment or sent in by mail. This packet requested demographic information and evaluated IPV. The response rate for the questionnaire packet was 87% for males and 90% for females.

IPV Measures

Self-Reported IPV

In Sample 1, the CTS-2 was used to assess IPV. Sixty-six items from the CTS-2 were used to measure: 1) psychological aggression (emotional and cognitive), 2) physical assault, 3) injury, and 4) sexual coercion. Thirty-three questions examine self-reported perpetration behaviors; 33 items ask for the respondent’s partner’s behavior (i.e. victimization by partner). The CTS-2 has been shown to have good reliability (α = .79–.95) and construct and discriminant validity (Straus et al., 1996). It has been long considered the “gold standard” for IPV assessment in both research and clinical work.

Police Reported Violence

Legal data on reports of IPV was gathered from justice system records via an online legal records system for Washington State. Direct reports of IPV or cases related to IPV found for couples between their time of enrollment and the time at which they should have completed all study procedures were documented.

Sample 2

Method

The procedures that couples from Sample 2 engaged in have been described in full elsewhere (Jacobson et al. 1994; Gottman et al., 1995). Therefore, only a brief description of participants, procedures, and measures relevant to the current paper are presented below.

Participants and Procedures

Participants (N = 121) were 18 years of age or older, able to speak and write English, and legally married. Couples participated in a laboratory assessment during which they independently completed self-report assessments of marital satisfaction and IPV.

Measures

Self-Reported IPV

In Sample 2, the original CTS (Straus, 1979) was used. The CTS is shorter than the CTS-2, consisting of 38 items (19 reflect respondent behavior and 19 reflect partner behavior). Subscales included: physical violence/assault and verbal/psychological aggression. The original measure had similar rates of reliability and validity to the CTS-2 (Straus, 1979). The CTS does not measure sexual coercion or injuries as a result of partner violence. The re-design of the CTS addressed certain criticisms of the original scale; namely, more items were added to better capture aspects of IPV and to improve the distinction between minor and severe forms of violence. The scoring and weighting between the CTS and CTS-2 are identical to one another (Straus et al., 1996), with the score ranges being higher for the CTS-2.

Couples were classified into three groups based on females’ responses to the CTS and their responses to the martial satisfaction surveys: 1) characterologically violent couples (CV; n = 61); 2) situationally violent couples (SV2Footnote 5; n = 27); and 3) distressed non-violent couples (DNV; n = 33). Couples were classified as CV based on the wife’s CTS report of her husband’s behavior. The CV classification was given if the husband had: 1) pushed, grabbed, shoved, slapped, hit, or tried to hit his wife six or more times; 2) kicked, bit, or hit his wife at least twice; 3) beat up, threatened with a gun/knife, or used a gun or knife on his wife at least twice. SV2 couples were classified as such when bilateral histories of violence were reported but did not reach the threshold set for the CV group. The DNV group reported no incidences of violence, but their scores on the DAS matched those of the CV group.

To reconcile differences between the ways violence was measured in the two samples, only items that appeared on both the CTS and CTS-2 were used in analyses. Items dealing with sexual coercion and injury were not included (as they were not available for Sample 2 couples). Items on the CTS-2 were re-classified based on the original CTS questions in instances where questions were not identical across the measures. Some questions were identical; for instance, “I stomped out of the room or house or yard during a disagreement” appeared on both versions. Many CTS-2 items comprised a single item on the CTS. An example is the CTS question, “I insulted or swore at my partner”. This statement appears on the CTS-2; however, “I called my partner fat or ugly” and “I accused my partner of being a lousy lover” also appear on the CTS-2. In instances such as these, the multiple CTS-2 items were summed and then averaged to be compatible with the original CTS. Items on the CTS did not have a CTS-2 counterpart were eliminated. Although similar, the reasoning and negotiation subscales were not used. After making revisions to both measures, a total of 20 items remained, 10 for perpetration, and 10 for victimization by partner. These items assessed two domains: psychological aggression (e.g. insults and threats) and physical assault (e.g. kick, hit, use of weapons). Scores on both domains can range from 0-125, with higher scores indicating more severe and chronic violence.

Police Reported Violence

No legal data was obtained from Sample 2.

Data Analysis

All data was verified and checked for normality prior to analysis. A series of multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) models with simple contrasts were performed for each partner separately to identify differences in IVP between groups (i.e., SV1, SV2, CV, and DNV).

Results

Hypothesis 1

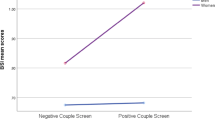

This hypothesis stated that self-reported violence for couples from Sample 1 (SV1) would differ from both the CV (SV1 reporting less IPV) and DNV (SV1 reporting more IPV) couples from Sample 2, but would not differ from the SV2 couples from Sample 2. To test this, two MANOVA were performed for each partner using the four self-reported IPV domains as the dependent variables (see Fig. 1). For males, a total of n = 197 had data available on IPV (CV group: n = 47; DNV group: n = 30; SV2 group: n = 26; SV1 group: n = 94). For females, a total of n = 209 had valid IPV data (CV group: n = 57; DNV group: n = 33; SV2 group: n = 24; SV1 group: n = 95). Significant differences were found between the four groups for both genders (males: λ = .57, F (12, 502) = 10.05, p < .001; females: λ = .52, F (12, 534) = 12.67, p < .001).

Male self-reported relationship violence by group, female self-reported relationship violence by group. + SV1: Situationally Violent, Sample 1; CV: Characterological Violent, Sample 2; DNV: Distressed Non-Violent, Sample 2, SV2: Situationally Violent, Sample 2. * Significantly different from SV1 group at p<.05; ** Significantly different from SV1 group at p<.001. − All results compared with MANOVA simple contrasts with the SV1 Group as the comparison group; Bars represent standard error

CV vs. SV1

The first simple contrast confirmed the hypothesis that SV1 differed from CV couples on all IPV variables. For physical assault perpetration (F (1, 193) = 47.00, p < .001) and victimization (F (1, 193) = 34.41, p < .001), CV males had significantly higher scores than SV1 males. For psychological aggression victimization (F (1, 193) = 40.34, p < .001) and perpetration (F (1, 193) = 5.45, p < .05), the same pattern was seen. For females, an identical pattern to males was seen, with CV females reporting more IPV (physical assault perpetration: F (1, 205) = 43.92, p < .001; victimization: F (1, 205) = 130.16, p < .001; psychological aggression victimization: F (1, 205) = 21.77, p < .001; perpetration: F (1, 205) = 4.51, p < .05).

SV2 vs. SV1

The second contrast showed that SV1 males differed significantly from SV2 males on psychological victimization (F (1, 193) = 10.73, p < .001); the SV1 group reported less psychological aggression victimization by their partners then did the SV2 group. As predicted, no differences were found on any remaining subscales (physical assault perpetration: p = .89; physical assault victimization: p = .92; psychological aggression perpetration: p = .20). Additional support for this hypothesis was seen with female partners; SV1 females did not differ from SV2 females on any subscales (psychological aggression: perpetration: p = .50; victimization: p = .15; physical assault: perpetration: p = .15; victimization: p = .96).

DNV vs. SV1

The final simple contrast revealed that SV1 males only differed from DNV males in terms of psychological aggression perpetration (F (1, 193) = 12.49, p < .001). SV1 reported more psychological aggression perpetration than did the DNV group. Psychological aggression victimization trended toward significance with DNV reporting less victimization than SV1 males (F (1, 193) = 3.52, p < .10). Although DNV males reported far less physical assault perpetration and victimization than did SV1 males, the differences were not significant. Conversely, SV1 females only differed from DNV females in terms of psychological aggression victimization (F (1, 205) = 6.48, p < .01). SV1 females reported more psychological aggression victimization than did DNV females. Psychological aggression perpetration trended toward significance with DNV reporting less victimization than SV1 males (F (1, 205) = 3.32, p < .10). Although DNV females reported far less perpetration and physical assault victimization than did SV1 females, the differences were not significant.

When examining self-reported IPV in the DNV group, five (17%) males reported being victims of low-level IPV and four (13%) reported perpetrating low-level IPV. For females, two (6%) reported being victims of low-level IPV and two (6%) reported perpetrating low-level IPV. Given that these levels were present in what was classified by researchers (Jacobson & Gottman 1998) as a non-violent group, we determined that the sample contained some situationally violent couples and was not a pure non-violent sample. To compare the SV1 group to a truly non-violent group, post-hoc, one-sample t-tests were performed. The purpose of this test was to compare physical assault means of SV1 couples to a value of zero (which would represent a truly non-violent group). Results indicated that physical assault rates for SV1 couples (both partners) were significantly different from zero (perpetration: p < .001; victimization: p < .001).

Due to similarities between the DNV and SV1 groups, additional MANOVA contrasts were performed to test if SV2 couples differed when compared to DNV couples. Contrasts revealed that DNV males differed from SV2 males on psychological aggression victimization (F (1, 193) = 15.52, p < .01), but did not differ on other forms of violence. This shows a similar pattern to SV1 males, indicating that SV2 males were similar to DNV males. For females, contrasts revealed that the DNV group did not differ from the SV2 group (psychological aggression: perpetration: p = .50; victimization: p = .15; physical assault: perpetration: p = .15; victimization: p = .15). Findings indicate that SV2 couples were similar to DNV couples and further demonstrate the similarities between the SV1 and SV2 groups.

Hypothesis 2

We hypothesized that the IJS would be an effective screening tool and would enable identification of situationally violent couples versus couples who exhibit characterological violence or no violence. More specifically, the hypothesis stated that couples screened in by IJS scores alone would not differ from couples that disclosed situational violence via the revised version of the CTS-2. The SV1 group was divided into two separate groups: (1) couples who were screened in based on self-reported situational violence (no-IJS; n = 65), and (2) couples who did not report situational violence but appeared to experience situational violence based on their IJS scores (IJS; n = 63). Since the comparison only involved couples from Sample 1 and all couples in Sample 1 completed the CTS-2, the suggested/original CTS-2 aggregate scores (Straus et al., 1996) were used to assess self-reported victimization and perpetration across the following domains: (1) psychological aggression, (2) physical assault, (3) sexual assault, and (4) injuries sustained during IPV. Additional MANOVA analyses were performed for each partner examining the differences across self-reported domains (see Figs. 2 and 3).

Male self-reported relationship violence by intimate justice scale (IJS) screening groups. + No-IJS: Indicates that participants were not screened-in with the IJS; IJS: Indicates the participants were screened-in based solely on their IJS scores.  Report of injury sustained as a result of intimate partner violence. Perpetration indicates that respondent’s behavior caused injury to spouse. Victimization indicates that spouse’s behavior caused injury to respondent. * Significantly different at p < .05; **Significantly different at p < .001. − Bars represent standard error

Report of injury sustained as a result of intimate partner violence. Perpetration indicates that respondent’s behavior caused injury to spouse. Victimization indicates that spouse’s behavior caused injury to respondent. * Significantly different at p < .05; **Significantly different at p < .001. − Bars represent standard error

Female self-reported relationship violence by intimate justice scale (ijs) screening groups. + No-IJS: Indicates that participants were not screened-in with the IJS; IJS: Indicates the participants were screened-in based solely on their IJS scores.  Report of injury sustained as a result of intimate partner violence. Perpetration indicates that respondent’s behavior caused injury to spouse. Victimization indicates that spouse’s behavior caused injury to respondent. * Significantly different at p < .05; **Significantly different at p < .001. − Bars represent standard error

Report of injury sustained as a result of intimate partner violence. Perpetration indicates that respondent’s behavior caused injury to spouse. Victimization indicates that spouse’s behavior caused injury to respondent. * Significantly different at p < .05; **Significantly different at p < .001. − Bars represent standard error

Males

A total of n = 61 (IJS, n = 32; No IJS, n = 29) had self-reported IPV data. No significant group effects were found (λ = .92, F (8, 52) = .60, p = .77). Univariate analyses revealed no differences on any of the four domains. These results indicate that the IJS and No-IJS groups self-reported similar rates of IPV perpetration and victimization.

Females

The same was analyses were repeated for female participants. For females, n = 86 (IJS: n = 42; No-IJS: n = 44) had usable data for self-reported IPV. Significant group differences were found (λ = .818, F (8, 77) = 2.14, p < .05). Univariate results revealed significant differences on the following: (1) psychological aggression perpetration: F (1, 84), = 7.36, p < .01, (2) psychological aggression victimization: F (1, 84), = 9.40, p < .01, (3) physical assault perpetration: F (1, 84), = 4.04, p < .05, (4) physical assault victimization: F (1, 84), = 11.67, p < .001. In all instances, the no-IJS group reported higher levels of perpetration and victimization of IPV. Couples did not differ significantly in terms of sexual coercion or injury.

Due to significant findings with females, subsequent MANOVA analyses were performed. The goal of the analyses was to determine if IJS couples from Sample 1 differed from couples from Sample 2. The hypothesis stated that IJS participants would show an identical pattern of IPV to that exhibited by SV1 couples when compared to the three groups (CV, DNV, SV2) from Sample 2. Results for both males and females revealed a similar pattern to the overall SV1 group. IJS couples differed significantly from CV couples across all domains of IPV. Additionally, an identical pattern to the findings seen in Hypothesis 1 was found between the IJS group and the DNV and SV2 groups. These results indicate that although IJS females reported less IPV perpetration and victimization than No-IJS females, they seemingly did not influence the overall SV1 group analysis (since patterns of differences across groups were comparable when using the entire SV1 group and only the IJS group from Sample 1).

Hypothesis 3

We hypothesized that the screener used in Sample 1 would effectively screen out characterologically violent couples and that this would lead to a lack of IPV reports to local law enforcement. Upon examination of police records for all Sample 1 couples, five screened-in couples from the overall group of 115 (4.3%) had incidences of IPV according to police reports. Four of these couples reported incidences of situational violence to our interviewers during screening. Of those couples, two reported IJS scores in the situational violence range. One couple screened in based on IJS scores alone. IPV data was available for four of these couples. All scores on the CTS-2 subscales were within low-level ranges. No instances of self-reported injury or sexual coercion were indicated by either partner. In all instances, once these cases were identified, research and clinical staff provided resource lists to the couples and assessed safety (as was done when instances of characterological violence were found via the telephone screen).

Discussion

This paper examined the efficacy of a screening instrument designed to differentiate between couples experiencing situational violence versus more severe characterological violence versus no violence at all. The screening tool was evaluated by comparing couples who were identified as experiencing situational violence (SV1) via the screening instrument to previously collected samples of characterologically violent couples (CV), distressed non-violent couples (DNV), and situationally violent couples (SV2). All four groups of couples were compared based on self-reported IPV. Results support the efficacy of the screening instrument to properly distinguish between situationally violent, characterologically violent, and non-violent couples.

CV versus SV1

Significant differences were seen between CV and SV1 couples for IPV. Both male and female partners from CV couples reported being the perpetrators and victims of more psychological aggression and physical assault than SV1 couples. These findings support the screening instrument’s utility to distinguish between characterologically and situationally violent couples. Additionally, results support Johnson’s (2001) IPV typology work. According to Johnson, situationally violent couples are highly distressed couples whose conflict escalates and may then prompt them to exhibit infrequent, low-level physical violence, such as pushing and shoving, as a means of conflict resolution. Thus, it would be expected that the SV1 couples would be different from CV couples as far as the level and severity of violence that is reported.

SV2 versus SV1

SV1 and SV2 couples did not differ in terms of most IPV domains. One exception was with male psychological aggression victimization. Males from the groups differed significantly, with SV1 males reporting less victimization than SV2 males. Based on these findings, our screening instrument appears to be effective at identifying couples experiencing situational violence, as the situationally violent couples identified via the screening tool were generally comparable to those from a previously collected sample of situationally violent couples. Significant difference seen between groups (i.e., male psychological aggression victimization) may be due to variation in measurement across studies discussed later in this section.

DNV versus SV1

SV1 couples’ reports of violence differed significantly from DNV couples; specifically, SV1 couples reported more psychological aggression perpetration for males and psychological aggression victimization for females than DNV. No significant differences were found between SV1 and DNV couples on other violence domains (i.e. physical assault perpetration or victimization). Similar patterns were found in post-hoc comparisons of SV2 and DNV couples, where the groups only differed significantly on psychological aggression, suggesting again that both situationally violent groups were comparable and distinct from DNV couples.

These findings are interesting given Johnson’s (2001) IPV typologies. It would be expected that the SV1 and SV2 groups would be different from CV couples as far as level and severity of violence, which the data supported. Additionally, given that situationally violent couples are highly distressed, one might expect them to be more closely related to DNV couples on facets of psychological aggression. These groups were expected to differ, though, in terms of physical assault, both in perpetration and victimization. Contrary to hypotheses, the opposite was found; differences between the groups were not significant for any physical assault domains, but were significant for the psychological aggression domains. When inspecting levels of physical violence, the two groups of situationally violent couples (SV1 and SV1) reported more physical violence (both perpetration and victimization) than the DNV couples. Additional inspection of the DNV group showed that both partners reported being both the perpetrators and victims of low-level violence (i.e., a few instances of pushing/shoving or throwing of objects was reported by DNV couples), suggesting that DNV couples may not have been a truly non-violent group.

To address the question of whether or not SV1 couples’ violence differed from a true no-violence group, post hoc analyses were run comparing SV1 mean levels of reported violence to a value of zero, indicating a complete absence of IPV. Analyses revealed that SV1 couples did have significantly higher rates of physical assault when compared to a value of zero. This indicates that some participants from Sample 2 (in the DNV group) may have been misclassified as non-violent, which would explain the lack of significant differences across physical violence domains. Future studies that attempt to categorize couples as either distressed non-violent or violent should ensure that non-violent couples truly show a complete absence of violence. Such delineation would further our knowledge regarding potential similarities and differences between distressed non-violent and situationally violent couples.

Examination of these groups (SV1, SV2, DNV, CV) supports the notion that the level of violence that couples experience may fall on a continuum, with all three groups (DNV, SV, and CV) being qualitatively different and falling within different places along the continuum: situationally violent couples may report more violence than distressed non-violent couples, but less violence than characterlogically violent couples. From the current work, the screening instrument can easily distinguish between CV and SV1 couples in terms of self-reported violence. The screener seems less apt at discriminating between SV1 and DNV, as few differences between these two groups were significant. Future research might benefit from further clarifying the distinctions between situationally violent and distressed non-violent couples, as these groups were not found to differ much in the current work. Additionally, research on the communication styles between these two groups is warranted in order to discover how interaction patterns differ between distressed non-violent and situationally violent couples and how conflict may evolve into violence. This distinction would be important to identify in order to further discriminate between these two groups for research or clinical purposes.

The Efficacy of the IJS

The use of the IJS in the screening instrument appears to have been generally effective in identifying situational violence among males and females, despite some gender differences. For males, no group differences were found across violence domains between couples screened in using the IJS alone (IJS group) versus those screened in by disclosing situational violence on the modified CTS-2 (No-IJS group). The two groups reported similar rates of IPV perpetration and victimization. Females who screened in based on IJS scores alone reported significantly less perpetration and victimization of psychological aggression and physical assault then did females screened in based on the actual disclosure of situational violence. Although significant differences were found, these differences did not influence the results from the overall group comparisons. Follow-up analyses, which separated SV1 couples into an IJS and No-IJS group and compared both groups with the three groups from Sample 2 (i.e., SV2, CV, and DNV), revealed that IJS and No-IJS female groups yielded identical patterns across IPV domains to the overall group. Given this, we can conclude that those screened in based on their IJS scores alone were still situationally violent and appropriately categorized as such.

This being said, an interesting gender effect may be present given that significant differences were seen among the IJS versus No-IJS females. Analyses showed No-IJS females reported more IPV than those screened in via the IJS; this was not true for male participants. Researchers have found gender differences in IPV reporting style (Chan, 2011; Dutton & Nicholls, 2005; Jory, 2004; Dobash & Dobash, 2004; Caetano et al. 2002; Archer, 2000) with studies finding varying rates of underreporting for both men and women (Chan, 2011); such differences in reporting may help to explain gender difference in the current work. It could be that men experiencing situational violence were equally as likely to disclose relationship dynamics that are predictive of IPV via the IJS as they were to directly report instances of violence via the modified version of the CTS-2. This suggests that use of the IJS or the CTS would enable identification of groups of highly comparable, situationally violent men.

In contrast, use of the IJS versus modified CTS-2 with women may not allow for identification of comparable groups, as IJS females had lower levels of IPV than did No-IJS females. This suggests that, for females, use of the IJS alone may be less sensitive toward identifying females who exhibit higher levels of situational violence. Overall, the IJS may be best used in conjunction with other assessments (which supports Jory’s suggestions), such as the CTS, to most accurately discriminate between characterological violence versus situational violence versus non-violence in both men and women to determine proper treatment options.

Examination of Legal Data

Legal data generally supported the efficacy of the screening tool to identify situationally violent versus characterologically violent versus non-violent couples. Only five couples had records of domestic violence incidences that resulted in police involvement and/or legal action. These couples all screened in based on disclosure of situational violence via the modified CTS-2. CTS-2 reports from both partners confirmed the presence of situational violence and were well below the mean for CV couples, indicating that escalation of violence from the time of screening until assessment was not present. Caution must be taken when interpreting these results as victim/perpetrator and severity data were not provided by legal records. It is, thus, possible that these couples may have been situationally violent. Washington State institutes strict domestic violence enforcement laws in order to protect potential victims. Under Washington State law [RCW 10.31.100(2) (c)], a law enforcement officer must make a mandatory arrest during domestic violence responses. Even when evidence of mutual violence is present, the responding officer must make a judgment call and arrest the partner they feel is the primary aggressor. Additionally, only a judge can drop charges against the offending partner. The victimized partner is deemed a witness for the state and has no authority to withdraw charges. Although Washington State should receive praise for its attempts to protect victims of IPV, this represents a limitation in this research, as these records cannot serve as full proof of misclassification.

Study Limitations

In addition to possible underreporting of IPV, several other limitations warrant caution when interpreting findings. Data from Sample 2 was collected in the early 1990s; therefore, all data were measured via older versions of the CTS. CTS-2 scores from Study1 had to be collapsed and composites created in order to more closely match the original CTS used in Study 2. As a result, measurement error may have been introduced.

Another limitation is lack of follow-up on couples who screened out of Study 1. The screening tool was designed to differentiate characterological violence from situational violence from couples who experienced no violence at all. Once couples were screened in based on presence of situational violence, they were invited to participate in the in-home assessment. Screened out couples were not invited to participate in this assessment; thus, we have no follow-up data that speaks to levels of IPV outside of data obtained from initial screening. Due to this lack of follow-up, it cannot be determined if couples who were screened out for presence of characterological violence or lack of situational violence were correctly categorized. Future research should focus on identification of which aspects of the screening instrument (e.g. IJS, CTS) most precisely influenced correct categorization. Concurrent validity of the screening instrument should also be tested against other measures used to screen couples for therapy.

The final limitation deals with the typology classifications of Sample 2. This study was performed prior to the inception of Johnson’s (2001) IPV typologies. Therefore, the classification into characterological, situational, and distressed non-violent was based on a more traditional concept of IPV. Jacobson and Gottman (1998) classified couples based on wife report of the following: (1) 6 or more episodes of low-level violence, or (2) two or more episodes of high-level violence, or (3) one episode of potentially lethal violence. Based on these criteria, couples could report infrequent low-levels of violence and still be classified as distressed non-violent; whereas, couples from Sample 1 were classified as situationally violent based on this type of disclosure. We believe that this classification led to the small effect sizes seen in IPV contrasts between SV1 and DNV groups. Given that data from Sample 2 was originally analyzed based on Jacobsen and Gottman’s original classification, a re-classification of the DNV and SV2 was inappropriate.

Utility of Screener

The goal of screening in clinical environments is to determine proper treatment options given couple characteristics. In the case of treating IPV in a couples therapy context, the identification of characterological violence is essential for safety reasons; conjoint treatment has been deemed inappropriate when such violence is present (Holtzworth-Munroe, 2001). Since the screener was successful in correctly differentiating between characterologically violent and situationally violent couples, it may be a useful tool within clinical settings. Based on current results, SV1 couples most closely resembled distressed, non-violent couples, followed by situationally violent couples from Sample 2. Therefore, it appears that the screening instrument may be somewhat conservative with regards to exclusion of couples who exhibit higher levels of violence. This conservative estimate may be beneficial within clinical settings that aim to ensure that characterologically violent couples are not referred to conjoint therapy.

With the success of the screener in this context, researchers and clinicians can begin to create various treatment programs geared towards situational violence; few of these empirically-validated programs exist. Stith et al. (2002) developed the Domestic Violence Focused Couples Treatment, which combines various theoretical aspects of multiple treatment modalities. Post-treatment effects show improvement in marital satisfaction and decreased levels of violence. Simpson et al. (2007) used non-aggression focused therapy with situationally violent couples and found that treatment did not increase violence; significant decreases in violence were seen once individual functioning improved. Finally, Bradley et al. (2011) reported effects of the psychoeducational program mentioned in this paper. The workshop was successful in reducing conflict, providing better conflict management skills, and increasing relationship satisfaction in situationally violent couples.

The use of this screening instrument within research contexts may allow for identification of situational versus characterological violence. However, additional research is needed to further develop a screening tool that allows for differentiation between situationally violent and distressed, non-violent couples. Although we correctly differentiated between characterologically and situationally violent couples, the situationally violent couples did not differ from the distressed non-violent group on self-reported IPV. The fact that self-reported IPV did not differ between situationally violent and distressed non-violent couples may have been due to a function of effect size rather than the screening instrument itself, since situationally violent couples did report more IPV than distressed, non-violent couples; the differences were so small (i.e. small effect sizes), they may not have been detectable with current sample sizes. Future research may be able to address this issue by increasing sample size.

Conclusion

This project was part of a larger study designed to determine the efficacy of a conjoint, psycho-educational workshop designed to reduce situational violence and improve couples’ relationships. Safe implementation of this treatment was crucial. Based on study results, the screening instrument was generally successful in differentiating between characterologically violent and situationally violent couples. Additionally, these results support the typologies of IPV introduced by Johnson (2001). Although the hypothesized differences were seen between the characterological and situationally violent groups, significant differences were not found between distressed, non-violent, and situationally violent groups. This latter finding may be due to methodological confounds. Future research should attempt to examine these groups (including a pure distressed non-violent group) more fully, specifically regarding conflict style and escalation, and develop a technique to better delineate between these two groups. In conclusion, the screening instrument can be used to delineate characterological violence and situational violence and can be used for research or clinical purposes.

Notes

Only a portion of couples were administered the IJS during screening procedures. See Method section for more information.

Eligibility for the study was based on the following criteria: 1) couples must be romantically involved and in a committed relationship for at least one year; 2) be 18 years of age or older, 3) speak fluent English; 4) be experiencing situational violence; 5) have at least one child under age 12 living in the home; 6) have a combined income below the local county median for a family of three ($73,000); 7) not be experiencing characterological violence, significant substance abuse issues, or have a positive screen for Antisocial Personality Disorder.

For a full copy of the screening instrument and script, please contact the first author.

The IJS was added to the screening instrument mid-way through the study in response to lower than expected rates of individuals who endorsed experiences of IPV via the modified version of the CTS-2. Therefore, not all couples completed the IJS during the screening process.

References

Archer, J. (2000). Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 126(5), 651–680.

Babcock, J. C., & La Taillade, J. J. (2000). Evaluating interventions for men who batter. In J. P. Vincent & E. N. Jouriles (Eds.), Domestic violence: Guidelines for research-informed practice (pp. 37–77). London: Jessica Kingsley.

Babcock, J. C., Green, C. E., & Robie, C. (2004). Does batterers’ treatment work? A meta-analytic review of domestic violence treatment. Clinical Psychology Review, 23, 1023–1053.

Babor, T. F., de la Fuente, J. R., Saunders, J., & Grant, M. (1992). AUDIT: The alcohol use disorders identification test: Guidelines for use in primary health care. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Bogard, M., & Mederos, F. (1999). Battering and couples therapy: Universal screening and selection of treatment modality. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 25(3), 291–312.

Bradford, K. (2010). Screening couples for intimate partner violence. Journal of Family Psychotherapy, 21, 76–82.

Bradley, R. P. C., Friend, D. J., & Gottman, J. M. (2011). Creating healthy relationships in low-income, distressed couples: Reducing conflict and encouraging relationship skills and satisfaction. Journal of Couples and Relationship Therapy, 10(2), 1–20.

Caetano, R., Schafer, J., Field, C., & Nelson, S. (2002). Agreements on reporting of intimate partner violence among White, Black and Hispanic couples in the United States. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24(12), 1308–1322.

Carlson, R. G., & Jones, K. D. (2010). Continuum of conflict and control: A conceptualization of intimate partner violence typologies. The Family Journal: Counseling and Therapy for Couples and Families, 18(3), 248–254.

Cascardi, M., Langhinrichsen, J., & Vivian, D. (1992). Marital aggression: Impact, injury, and health correlates for husbands and wives. Archives of Internal Medicine, 152, 1178–1184.

Chan, K. (2011). Gender differences in self-reports of intimate partner violence: A review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 16, 167–175.

Coan, J., Gottman, J. M., Babcock, J., & Jacobson, N. S. (1997). Battering and the male rejection of influence from women. Aggressive Behavior, 23(5), 375–388.

Costa, D. M., & Babcock, J. C. (2008). Articulated thoughts of intimate partner abusive men during anger arousal: Correlates with personality disorder features. Journal of Family Violence, 23, 395–402.

Dobash, R. E., & Dobash, R. E. (2004). Women’s violence to men in intimate relationships: Working on a puzzle. British Journal of Criminology, 44(3), 324–349.

Dutton, D. G., & Nicholls, T. L. (2005). The gender paradigm in domestic violence research and theory: Part 1—the conflict of theory and data. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 10(6), 680–714.

Ehrensaft, M. K., & Vivian, D. (1996). Spouses’ reasons for not reporting existing marital aggression as a marital problem. Journal of Family Psychology, 10, 443–453.

First, M. B., Spitzer, M. B., Gibbon, M., & Williams, J. B. W. (1995). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV Axis I Disorders—patient edition (SCID-I/P, Version 2.0). New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute.

Gottman, J. M., Jacobson, N. S., Rushe, R. H., Shortt, J. W., Babcock, J., La Taillade, J. J., et al. (1995). The relationship between heart rate reactivity, emotionally aggressive behavior, and general violence in batterers. Journal of Family Psychology, 9(3), 227–248.

Harris, G. E. (2006). Conjoint therapy and domestic violence: Treating the individuals and the relationship. Counseling Psychology Quarterly, 19(4), 373–379.

Holtzworth-Munroe, A. (2001). Standards for batterer treatment programs: How can research inform our decisions? Journal of Aggression Maltreatment & Trauma, 5(2), 165–180.

Holtzworth-Munroe, A., & Stuart, G. L. (1994). Treatment of marital violence. In L. van de Creek & S. Knapp (Eds.), Innovations in clinical practice: A source book (Vol. 13, pp. 5–19). Sarasota: Professional Resource Press.

Jacobson, N. S., Gottman, J. M., Waltz, J., Rushe, R., Babcock, J., & Holtzworth-Munroe, A. (1994). Affect, verbal content, and psychophysiology in the arguments of couples with a violent husband. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62(5), 982–988.

Jacobson, N. S., & Gottman, J. M. (1998). When men batter women: New insights into ending abusive relationships. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Johnson, M. P. (1995). Patriarchal terrorism and common couple violence: Two forms of violence against women. Journal of Marriage & the Family, 57(2), 283–294.

Johnson, H. (2000). The role of alcohol in male partners’ assaults on wives. Journal of Drug Issues, 30(4), 725–740.

Johnson, M. P., & Ferraro, K. (2000). Research on domestic violence in the 1990’s: Making distinctions. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 948–963.

Johnson, M. P. (2001). Conflict and control: Symmetry and asymmetry in domestic violence. In A. Booth, A. C. Crouter, & M. Clements (Eds.), Couples in conflict (pp. 95–104). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Johnson, M. P., & Leone, J. M. (2005). The differential effects of intimate terrorism and situational couple violence: findings from the national violence against women survey. Journal of Family Issues, 26(3), 322–349.

Johnson, M. P. (2006). Conflict and control: Gender symmetry and asymmetry in domestic violence. Violence Against Women, 12(11), 1003–1018.

Jory, B. (2004). The intimate justice scale: An instrument to screen for psychological abuse and physical violence in clinical practice. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 30, 29–44.

Kelly, J. B., & Johnson, M. P. (2008). Differentiation among types of intimate partner violence: Research update and implications for interventions. Family Court Review, 46(3), 476–499.

Leone, J. M., Johnson, M. P., & Cohan, C. L. (2007). Victim help seeking: Differences between intimate terrorism and situational couple violence. Family Relations, 56, 427–439.

Locke, H. J., & Wallace, K. M. (1959). Short marital-adjustment and prediction tests: Their reliability and validity. Marriage and Family Living, 21(3), 251–255.

O’Leary, K. D., Vivian, D., & Malone, J. (1992). Assessment of physical aggression against women in marriage: The need for multimodal assessment. Behavioral Assessment, 14, 5–14.

Pence, E., & Paymar, M. (1993). Education group for men who batter: The Duluth Model. New York: Springer Publishing.

Rabin, R. F., Jennings, J. M., Campbell, J. C., & Bair-Merritt, M. H. (2009). Intimate partner violence screening tools. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 36(5), 439–445.

Ross, J. M., & Babcock, J. C. (2009). Proactive and reactive violence among intimate partner violent men diagnosed with antisocial and borderline personality disorder. Journal of Family Violence, 24, 607–617.

Schacht, R. L., Dimidjian, S., George, W. H., & Berns, S. B. (2009). Domestic violence assessment procedures among couple therapists. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 35(1), 47–59.

Simpson, L. E., Doss, B. D., Wheeler, J., & Christensen, A. (2007). Relationship violence among couples seeking therapy: Common couple violence or battering? Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 33(2), 270–283.

Simpson, L. E., Atkins, D. C., Gattis, K. S., & Christensen, A. (2008). Low-level relationship aggression and couple therapy. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(1), 102–111.

Skinner, H. A. (1982). The drug abuse screening test. Addictive Behaviors, 7(4), 363–371.

Spanier, G. B. (1976). Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and Family, 38(1), 15–28.

Stith, S. M., Rosen, K. H., & McCollum, E. E. (2002). Developing a manualized couples treatment for domestic violence: Overcoming challenges. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 28(1), 21–25.

Stith, S. M., Rosen, K. H., & McCollum, E. E. (2003). Effectiveness of couples treatment for spouse abuse. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 29(3), 407–426.

Stith, S. M., Rosen, K. H., McCollum, E. E., & Thomsen, C. J. (2004). Treating intimate partner violence within intact couple relationships: Outcomes of multi-couple versus individual couple therapy. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 30(3), 305–318.

Straus, M. A. (1979). Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS). Journal of Marriage and Family, 41(1), 75–88.

Straus, M. A., & Gelles, R. J. (1986). Societal change and change in family violence from 1975 to 1985 as revealed by two national surveys. Journal of Marriage and Family, 48(3), 465–479.

Straus, M. A., Hamby, S. L., Boney-McCoy, S., & Sugarman, D. (1996). The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues, 17, 283–316.

Todahl, J. L., Linville, D., Chou, L., & Maher-Cosenza, P. (2008). A qualitative study of intimate partner violence universal screening by family therapy interns: Implications for practice, research, training and supervision. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 34(1), 28–43.

Todahl, J., & Walters, E. (2009). Universal Screening for intimate partner violence: A systematic review. Journal of Marital & Family Therapy

Todahl, J. L., & Walters, E. (2009b). Universal screening and assessment for intimate partner violence: The IPV screen and assessment tier (IPV-SAT) model. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy, 21, 247–270.

Tweed, R. G., & Dutton, D. G. (1998). A comparison of impulsive and instrumental subgroups of batterers. Violence and Victims, 13(3), 217–230.

Waltz, J., Babcock, J., Jacobson, N., & Gottman, J. M. (2000). Testing a typology of batterers. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 68(4), 658–669.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by a grant (#90OJ2022) from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families (ACF). The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of ACF.

We would like to express our gratitude to the following people who helped make this project possible: Julie Babcock, Robin Dion, Julie Gottman, Michael Johnson, Anne Menard, Sandra Stith, Oliver Williams and Daniel Yoshimoto.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Friend, D.J., Cleary Bradley, R.P., Thatcher, R. et al. Typologies of Intimate Partner Violence: Evaluation of a Screening Instrument for Differentiation. J Fam Viol 26, 551–563 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-011-9392-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-011-9392-2