Abstract

The purpose of this study was to investigate intergenerational relationships between trauma and dissociation. Short and long term consequences of betrayal trauma (i.e., trauma perpetrated by someone with whom the victim is very close) on dissociation were examined in a sample of 67 mother–child dyads using group comparison and regression strategies. Experiences of high betrayal trauma were found to be related to higher levels of dissociation in both children and mothers. Furthermore, mothers who experienced high betrayal trauma in childhood and were subsequently interpersonally revictimized in adulthood were shown to have higher levels of dissociation than non-revictimized mothers. Maternal revictimization status was associated with child interpersonal trauma history. These results suggest that dissociation from a history of childhood betrayal trauma may involve a persistent unawareness of future threats to both self and children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Trauma perpetrated against a child by a parent or close other has been shown to lead to dissociation. Dissociation, defined in the DSM-IV as “a disruption in the usually integrated functions of consciousness, memory, identity, or perception of the environment,” (American Psychiatric Association 2000) has been conceptualized as a defensive response to trauma (e.g., Liotti et al. 1999; Lyons-Ruth 2003; McLewin and Muller 2006; Peterson and Putnam 1994; Putnam 1997; Sanders 1992). Although the adoption of dissociative strategies to deal with emotions may be adaptive in the trauma context, it is often maladaptive in other settings (Putnam 1997).

Betrayal Trauma Theory (Freyd 1994, 1996) posits that dissociation is most likely to occur when a trauma is perpetrated by someone with whom the victim has a close relationship. Research has shown that exposure to traumas high in betrayal is significantly associated with dissociation (e.g., DePrince 2005; Freyd et al. 2001, 2005). In the case of child maltreatment, betrayal trauma theory suggests that a child who is dependent on his/her parent learns to dissociate the experience of parental betrayal and abuse from conscious awareness, in order to maintain an attachment to that parent.

Several studies have identified a link between the experience of maltreatment and heightened dissociation in children (Becker-Blease et al. 2004; Hulette et al. 2008a, b; Macfie et al. 2001a, b; Ogawa et al. 1997). For example, Hulette and colleagues (2008a, b) found that maltreated preschool-age children in foster care had a significantly higher mean level of dissociation than non-maltreated children. Children who experienced multiple forms of maltreatment were the most highly dissociative. These findings are in accord with betrayal trauma theory (Freyd 1996), as children experiencing different kinds of abuse may have a greater need to be dissociative in order to preserve a relationship with caregivers. Betrayal trauma seems to have long-term effects on dissociation as well. In a prospective longitudinal study, Ogawa et al. (1997) found that maltreatment predicted dissociation across developmental periods (i.e., infancy, preschool, elementary school, adolescence, and young adulthood). Dissociation is also present in adult survivors of childhood betrayal trauma (Coons et al. 1988; Loewenstein and Putnam 1990; Putnam 1997; Putnam et al. 1986; Ross et al. 1991).

Persisting dissociative tendencies may be harmful, as individuals may have difficulties identifying future interpersonal threats in the environment. Research has shown high levels of interpersonal revictimization among adults with histories of betrayal trauma (e.g., Cloitre 1997; Messman-Moore 2000; Sandberg 2001). DePrince (2005) found that adults with a childhood betrayal trauma history and who were also revictimized after age 18 made significantly more errors on social contract and precautionary rule problem sets than non-revictimized adults on the Wason Selection Task (Cosmides 1989; Stone et al. 2002), which is designed to test subjects’ ability to detect violations of conditional rules. Furthermore, pathological dissociation predicted these errors. This suggests that dissociation from a history of betrayal trauma may place individuals at high risk for revictimization; they may be less likely to detect violations of social contracts and unsafe situations because they learned in the past that it was adaptive to be unaware of such problems (DePrince 2005; Freyd 1996).

Dissociation may therefore be a mechanism by which the revictimization of childhood abuse survivors occurs in adulthood. It is also possible that when adults with a betrayal trauma history become parents, high levels of dissociation may contribute to an unawareness of dangers in the environment that can affect their children. For example, Chu and DePrince (2006) found that children with a betrayal trauma history had mothers with higher numbers of betrayal traumas versus children with no such history. They suggested that maternal dissociation may lead to difficulties monitoring their children. The role of dissociation in the intergenerational transmission of trauma is one that requires further investigation.

Study Hypotheses

Based on the literature, a cross-sectional study was planned to examine the following associations between trauma and dissociation in a sample of parents and children.

Child Hypotheses

-

1.1

Based on Betrayal Trauma Theory, it was expected that children who experienced traumas high in betrayal would have higher levels of dissociation than children who did not experience high betrayal traumas.

Parent Hypotheses

-

2.1

Based on Betrayal Trauma Theory, it was expected that mothers who experienced traumas high in betrayal would have higher levels of dissociation than mothers who did not experience high betrayal traumas.

-

2.2

The group of mothers who experienced high betrayal trauma in childhood and then experienced interpersonal traumas perpetrated against them in adulthood (i.e., were revictimized) will have higher levels of dissociation than mothers who were not revictimized in this way, providing support for the theory that dissociation stemming from childhood trauma may lead to deficits in awareness for future interpersonal threats in the environment.

Parent–child Relationship Hypotheses

-

3.1

Children’s history of trauma was hypothesized to be related to their mother’s history of trauma.

-

3.2

Children of revictimized mothers were expected to be more likely to experience interpersonal traumas than children of non-revictimized mothers. This was hypothesized because high levels of maternal dissociation may contribute to an unawareness of threatening individuals in the environment, leading to child trauma exposure (see also Hypothesis 2.2).

Method

Participants

Data were collected via a university database of families who were listed in the local birth register, posted fliers in the community, and electronic messages on websites and listserves. Participants were given a small monetary reimbursement and the children received a toy for their time. The study initially involved general recruitment of families with children aged 7–8, requesting participation from “children and parents who have, or have not, experienced stressful life events.” Due to a lack of child participants with trauma histories, during the second phase of recruitment we selectively sampled for a more targeted sample of families with 7–8 year old children who had experienced traumatic life events. Seventy-five children and their caregivers initially participated in the study. Data from eight families were excluded from analyses as the participating caregivers were not their biological mothers, resulting in a final sample size of 67 mothers and their children.

The age group of the children (7 to 8 year olds) was chosen because of the importance of examining children’s coping skills as they enter middle childhood. There were 36 boys and 31 girls in the sample. Families in the study identified the following ethnic backgrounds: 53 European-American, 4 Hispanic, 3 Native American, 1 Asian, and 5 “other” (all of whom reported mixed heritage). Two families declined to give information about ethnicity. Approximately 66% of families reported incomes at or below $30,000, 28.4% of families reported incomes higher than $30,000, and 4 families declined to give this information. Parents in the study ranged in age from 26 to 50 years old (M = 35.8, SD = 6.1). All parents reported completing high school or the equivalent; approximately 82% reported additional years of education.

Measures

Trauma History

Trauma histories of parent and child were assessed using the Brief Betrayal Trauma Survey (BBTS) and the Brief Betrayal Trauma Survey—Parent Report (BBTS-Parent). Due to the sensitive nature of the data, it was stressed to adults during data collection that no identifying information would be linked to any of the information provided. The BBTS (Goldberg and Freyd 2006) is a 14-item self-report inventory of adult trauma experiences and the BBTS-Parent (Becker-Blease et al. 2004) is a 12-item caregiver-report measure of traumatic events that were experienced by the parent’s child. These measures have shown good test-retest reliability and indicate trauma exposure rates that are similar to those found by other measures (Goldberg and Freyd 2006).

Events endorsed on the BBTS and the BBTS-Parent include traumatic experiences with a higher degree of betrayal (“high betrayal trauma” or HBT) and traumatic experiences with either a lesser degree of betrayal or no betrayal (“lesser betrayal trauma” or LBT); see Tables 1 and 2. In this study, the experience of traumas perpetrated by someone “very close” to the individual was classified as HBT. Participants were placed into the HBT category if they endorsed any events high in betrayal. Individuals who reported that they had not experienced HBT but had experienced traumas perpetrated by someone “not close,” witnessed interpersonal traumas, and non-interpersonal traumas were placed into the LBT category. Finally, individuals who did not report any trauma were categorized in the “no trauma” group, or NT. This hierarchical classification style is similar to other systems that categorize child maltreatment subtypes (e.g., Manly et al. 1994), and is based on guidelines established by Freyd (2008).

Among the mothers in the sample, 53 reported the experience of HBT, seven reported only LBT, and seven reported NT, indicating high rates of trauma. Note that on the BBTS, mothers were asked whether they had experienced traumatic events in childhood and in adulthood. Because only five mothers reported the experience of high betrayal in adulthood without the experience of high betrayal in childhood, and no differences were found on the outcomes of interest, these groups were combined and overall betrayal trauma was reported for most analyses, except where indicated. Regarding the children in the sample, parents reported that 21 had experienced HBT, 25 had experienced only LBT, and 21 had experienced only NT.

Dissociation

The Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES) is a 28-item adult self-report measure that provides information regarding a continuum of dissociative experiences (Carlson and Putnam 1993). The DES has been shown to have good overall psychometric properties including reliability, construct validity, and discriminant validity (Carlson and Putnam 1993; Carlson et al. 1993; van IJzendoorn and Schuengel 1996). Parents reported on their children’s level of dissociation using the Child Dissociative Checklist (CDC), a 20-item caregiver-report measure (Putnam et al. 1993) on which symptoms of child dissociation are rated over the prior 12 months on a three-point scale (0 = not true, 1 = somewhat true/sometimes true, 2 = very true). The CDC shows good test–retest stability and internal consistency, as well as good convergent and discriminant validity (Putnam et al. 1993; Putnam and Peterson 1994).

Results

Analyses of Child Sample

Child Hypothesis 1.1

Children who experienced traumas high in betrayal will have higher levels of dissociation than those without high betrayal trauma.

ANOVA was planned to test differences in dissociation between child trauma groups (see descriptive statistics in Table 3). Six parents reported child dissociation scores of 12 and above (which is suggestive of pathology). Out of these six children, two children with scores of 12 and 13 were in the LBT group, and four children with scores of 14, 15, 17, and 19 were in the HBT group.

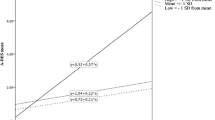

Due to strong positive skew, Child Dissociative Checklist (CDC) scores were log transformed prior to analysis. The ANOVA found a significant omnibus effect, F(2, 64) = 4.34, p = 0.02, partial η 2 = 0.12, with the linear contrast also significant, F(1, 64) = 8.27, p = 0.005. The pattern of means in Fig. 1 shows the highest dissociation level in the HBT group (M = 1.59, SD = 0.92), a decreased level in the LBT group (M = 1.34, SD = 0.90), and the lowest level in the NT group (M = 0.82, SD = 0.80). Posthoc contrasts using Tukey’s HSD tests found that the HBT and NT groups were significantly different, p = 0.02. HBT and LBT groups were not significantly different from one another, p = 0.61. LBT and NT groups were also not significantly different, p = 0.12.

Analyses of Parent Sample

Parent Hypothesis 2.1

Mothers who experienced traumas high in betrayal will have higher levels of dissociation than those without high betrayal trauma.

ANOVA was planned to test differences in dissociation between trauma groups among mothers in the sample (see descriptive statistics in Table 3). Prior to analysis, it was noted that the two mothers who reported dissociation scores above the pathological score cutoff of 30 were in the HBT group.

Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES) scores were log transformed for the ANOVA, and the Welch approximation was used. There was a significant omnibus effect for adult dissociation level, F(2, 10.44) = 12.61, p = 0.001, partial η 2 = 0.19. Furthermore, the weighted linear contrast was significant, F(1, 63) = 14.55, p < 0.001. Figure 2 depicts the pattern of means, in which dissociation scores were highest among those with HBT (M = 2.22, SD = 0.60), followed by LBT (M = 1.63, SD = 1.04), and NT (M = 1.36, SD = 0.39). Posthoc contrasts using Tukey’s HSD tests showed that the HBT and NT groups were significantly different, p = 0.004. HBT and LBT groups were marginally significantly different, p = 0.07. LBT and NT groups were not significantly different, p = 0.7.

Parent Hypothesis 2.2

The group of mothers who experienced high betrayal trauma in childhood and were revictimized in adulthood will have higher levels of dissociation than mothers who were not revictimized.

The BBTS categories used in the above parent analysis combined reports of betrayal trauma experienced in childhood and adulthood to create overall HBT, LBT, and NT categories. However, we were also interested in the group of mothers in the sample who had experienced childhood HBT and then again experienced interpersonal traumas perpetrated against them in adulthood (i.e., were revictimized). It was hypothesized that this group of revictimized mothers might have higher levels of dissociation than mothers who were not revictimized. Of the 67 mothers in the sample, 28 mothers who experienced HBT in childhood were revictimized in adulthood. Another 20 mothers had experienced HBT in childhood but were not revictimized in adulthood. After an examination of descriptive statistics (see Table 3), an independent samples t-test was completed using log-transformed DES scores and an accommodation for unequal variances, revealing that revictimized mothers had a significantly higher mean dissociation score (M = 2.31, SD = 0.66, n = 27) than non-revictimized mothers (M = 2.0, SD = 0.30, n = 18), t(39) = 2.10, p = 0.04.

Analyses of Parent–child Hypotheses

Parent–child Hypothesis 3.1

Child trauma history will be related to maternal trauma history.

To test the hypothesis that child betrayal trauma would be related to maternal betrayal trauma, a 2 × 2 chi-square with the Yates continuity correction was used. Those with interpersonal traumas were compared against those with no trauma or non-interpersonal traumas. Interpersonal trauma was defined to include HBT, traumas perpetrated by a not-close other, and witnessing violent acts by or against a close or not-close other. The analysis revealed a significant association between maternal and child interpersonal trauma; χ 2(1) = 8.10, p = 0.004, suggesting that a higher percentage of children with interpersonal trauma have parents who have had interpersonal trauma. Table 4 shows the distribution of the data.

Parent–child Hypothesis 3.2

Children of revictimized mothers were expected to be more likely to experience interpersonal traumas than children of non-revictimized mothers.

Analyses from Hypothesis 2.2 examined whether mothers who experienced high betrayal trauma in childhood and then again experienced high betrayal trauma in adulthood would have higher levels of dissociation than mothers who were not revictimized. It was also important to determine whether this set of mothers also might have children with higher rates of betrayal trauma, to understand whether a maternal unawareness of dangers in the environment might impact their children. The data were therefore tested to explore whether children with revictimized mothers were more likely to experience any kind of interpersonal traumas, as mothers may be less aware of the potential for child trauma perpetration by trusted or non-trusted individuals. A significant association between maternal revictimization status and child interpersonal trauma emerged, χ 2(1) = 4.01, p = 0.045 (see Table 5).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate intergenerational associations between trauma and dissociation in a cross-sectional study. By examining a sample of parents and children with and without histories of betrayal trauma, short and long term consequences on dissociation were explored.

Betrayal Trauma History

As this study seeks to understand how high betrayal trauma by a close other may impact other processes, it is important to closely examine the nature of the trauma in the 67 participating mother–child dyads. Mothers experienced a range of trauma, including multiple types of HBT and LBT. The experience of multiple types of maltreatment or victimization in childhood has been shown to be common (Finkelhor et al. 2005; Lau et al. 2005; Pears et al. 2008). Of the 53 mothers who reported HBT, 74.6% experienced emotional or psychological mistreatment by a close other. This type of abuse showed a great deal of overlap with the other forms of HBT that were reported, including sexual abuse by a close other (40.3%) and physical abuse by a close other (37.3%). Overall, the sample was highly traumatized, as approximately 79% of the mothers in the sample reported experiencing at least one form of HBT. In contrast, the child sample was fairly evenly distributed among HBT, LBT, and NT groups. Approximately 31% of children in the sample were reported to have experienced high betrayal trauma. Within the HBT group, emotional abuse by a close other was experienced by the majority of children (23.9% of child sample). Only three children reportedly experienced physical abuse by a close other, while another two children reportedly experienced sexual abuse by a close other. The trauma types represented here are important to consider with regard to the results. In future research it will be important to examine a larger sample of parents that include those without a history of betrayal trauma, as well as including children with a wider variety of high betrayal trauma experiences.

Dissociation and Betrayal Trauma

In both the parent and child samples, the experience of betrayal trauma was related to higher levels of dissociation. The expected linear pattern was observed in both groups, showing that those who had experienced HBT had the highest levels of dissociation, followed by those with LBT and then NT. The patterns, however, were slightly different for parents versus children. In parents, mean dissociation scores for HBT and LBT were marginally significantly different from one another, whereas child dissociation scores in HBT and LBT were too close to be significantly different. This finding may be attributable to the types of trauma in these groups. As noted above, children in the HBT group primarily experienced emotional abuse, while the child LBT group was characterized by a mix of witnessed interpersonal violence as well as experienced non-interpersonal traumas. It is possible that the experience of HBT involving a threat to one’s physical integrity (i.e., sexual abuse or physical abuse) might involve greater dissociation than betrayal trauma involving emotional abuse. Prior research by Hulette and colleagues (Hulette et al. 2008a, b) and Macfie and colleagues (2001a, b) suggests that maltreatment by a caregiver that includes sexual and/or physical abuse involves higher levels of dissociation than neglect or emotional abuse. With a sample of children with more diverse HBT experiences, higher levels of dissociation may have been present.

Dissociation and Unawareness of Future Threats

Dissociation was also examined as a possible explanation for a lowered maternal awareness of interpersonal threats in the environment that could lead to: a) revictimization in mothers who had experienced HBT in childhood and b) increased child exposure to interpersonal traumas. For these analyses, a subset of mothers who had experienced HBT in childhood and were revictimized in adulthood (i.e., experienced interpersonal traumas perpetrated directly against them) was compared against a group who had experienced HBT in childhood but were not revictimized in adulthood.

Maternal Dissociation and Revictimization

Revictimized mothers were shown to have a significantly higher mean level of dissociation than non-revictimized mothers, providing support for the idea that dissociation may indicate a lower threshold of awareness for potential future perpetrators (DePrince 2005). However, given that the current study is cross-sectional in design, there are several possible explanations for this finding. First, it may be that mothers in the revictimized group developed high dissociation following childhood HBT, levels of which stayed high into adulthood. Retention of high levels in adulthood could explain an increased risk for interpersonal traumas. In contrast, the non-revictimized group (who also experienced childhood HBT) may have developed high levels of dissociation in childhood, with levels dropping in adulthood. An alternative explanation is that the non-revictimized group may not have developed as high levels in childhood to begin with, perhaps due to other resilience factors that were in place. A longitudinal study would allow insights into long-term pathways of dissociation.

Maternal Dissociation and Increased Child Trauma Exposure

In order to determine if maternal dissociation could lead to increased child trauma exposure, the association between child trauma history and maternal trauma history was examined. The results of the chi-square suggested that children with interpersonal trauma were more likely to have mothers with interpersonal trauma. One hundred percent of children in the sample with histories of interpersonal trauma had mothers with interpersonal traumas, while 75% of children with non-interpersonal traumas or no traumas had parents with interpersonal trauma. Given that the parent sample experienced a great deal of trauma, high percentages of mothers with interpersonal trauma histories were found in both groups. A larger sample size would therefore be useful to establish a more accurate estimate of the relation between variables. Nonetheless, this analysis reveals a strong association between child and maternal interpersonal trauma histories.

A subsequent analysis examined maternal dissociation as a possible contributor to child interpersonal trauma exposure. Results discussed earlier established higher levels of dissociation among revictimized mothers than non-revictimized mothers, as they may be less aware of interpersonal threats to themselves. Similarly, maternal dissociation may lead to difficulties monitoring interpersonal threats to children. A chi-square test confirmed an association between maternal revictimization status and child interpersonal trauma. Seventy-two percent of children who experienced interpersonal trauma had revictimized mothers, while 28% of children who experienced interpersonal trauma had non-revictimized mothers; the differences in percentages here is striking.

Limitations and Future Directions

While this study has a number of significant findings, it is also important to note general limitations, as they provide valuable information about future research directions. One of the major limitations is the difficulty of drawing conclusions about causality because of the lack of temporal information. However, the ideas presented here provide the basis for subsequent studies. Future research may include prospective longitudinal studies that can examine trajectories of dissociation, such as how dissociation may be a risk factor for later trauma exposure for survivors and their children.

Another limitation of the current study involves the reliance on parent-report measures. Because the child trauma history was parent-reported, it may be that mothers did not report this information accurately and/or truthfully, despite the fact that no identifying information was attached to their data. Additionally, if parents are highly dissociative and less attuned to the external environment, they may misreport trauma histories and symptoms for themselves and their children. It will therefore be crucial to gather observational data or reports from other relevant individuals (e.g., teachers), as well as to study children with documented histories of maltreatment, when continuing this line of research.

Future work could also examine different types of samples. As mentioned, a parent–child sample with a more diverse history of experiences and a wider range of dissociation levels would provide useful distinctions between trauma types. It is additionally important to consider frequency and chronicity of trauma (Bolger and Patterson 2001; Manly et al. 1994), as well as developmental timing of traumatic experiences (Thornberry et al. 2001). In addition to these characteristics, other factors (e.g., maternal psychopathology, relationship of perpetrator to victim) should be identified and included in studies.

Despite the limitations listed above, this study examines a snapshot of time that suggests that the experience of parental trauma has intergenerational effects on children. Further research can not only provide clarification of the nature of the relationships between trauma and dissociation, but can also test interventions that may potentially reduce posttraumatic symptomatology in children.

Summary and Conclusions

To summarize, intergenerational associations between trauma and dissociation were revealed in this study. A major goal of the study was to understand how maternal trauma may contribute to child trauma and child adaptation to trauma. As expected, experiences of high betrayal trauma were found to be related to higher levels of dissociation in mothers. Evidence was also found that is consistent with the hypothesis that dissociation may result in impairments in maternal ability to protect children from trauma, and that these children appear to be at greater risk for dissociation following betrayal trauma.

This study overall provides compelling evidence that the experience of parental trauma has intergenerational effects on children. It is an exciting step towards longitudinal studies that can provide additional clarification of the nature of the associations between these variables, as well as parent–child intervention studies that may help to prevent child trauma exposure and reduce posttraumatic symptomatology.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR). Washington, DC.

Becker-Blease, K. A., Freyd, J. J., & Pears, K. C. (2004). Preschoolers’ memory for threatening information depends on trauma history and attentional context: implications for the development of dissociation. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 5(1), 113–131.

Bolger, K. E., & Patterson, C. J. (2001). Developmental pathways from child maltreatment to peer rejection. Child Development, 72, 549–568.

Carlson, E. B., & Putnam, F. W. (1993). An update on the dissociative experiences scale. Dissociation: Progress in the Dissociative Disorders, 6(1), 16–27.

Carlson, E. B., Putnam, F. W., Ross, C. A., Torem, M., et al. (1993). Validity of the dissociative experiences scale in screening for multiple personality disorder: a multicenter study. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 150(7), 1030–1036.

Chu, A., & DePrince, A. P. (2006). Development of dissociation: examining the relationship between parenting, maternal trauma and child dissociation. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 7(4), 75–89.

Cloitre, M. (1997). Posttraumatic stress disorder, self- and interpersonal dysfunction among sexually retraumatized women. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 10(3), 437–452.

Coons, P. M., Bowman, E. S., & Milstein, V. (1988). Multiple personality disorder: a clinical investigation of 50 cases. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 176(9), 519–527.

Cosmides, L. (1989). The logic of social exchange: has natural selection shaped how humans reason? Studies with the Wason selection task. Cognition, 31(3), 187–276.

DePrince, A. (2005). Social cognition and revictimization risk. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 6(1), 125–141.

Finkelhor, D., Ormrod, R., Turner, H., & Hamby, S. L. (2005). The victimization of children and youth: a comprehensive, national survey. Child Maltreatment, 10, 5–25.

Freyd, J. J. (1994). Betrayal trauma: traumatic amnesia as an adaptive response to childhood abuse. Ethics & Behavior, 4(4), 307–329.

Freyd, J. J. (1996). Betrayal trauma: The logic of forgetting childhood abuse. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Freyd, J. J. (2008). Suggested Categorization of BBTS Items. Retrieved September 1, 2009, from http://dynamic.uoregon.edu/∼jjf/bbts/categories.html.

Freyd, J. J., DePrince, A. P., & Zurbriggen, E. L. (2001). Self-reported memory for abuse depends upon victim-perpetrator relationship. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 2(3), 5–16.

Freyd, J. J., Klest, B., & Allard, C. B. (2005). Betrayal trauma: relationship to physical health, psychological distress, and a written disclosure intervention. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 6(3), 83–104.

Goldberg, L. R., & Freyd, J. J. (2006). Self-reports of potentially traumatic experiences in an adult community sample: gender differences and test-retest stabilities of the items in a brief betrayal-trauma survey. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 7(3), 39–63.

Hulette, A. C., Fisher, P. A., Kim, H. K., Ganger, W., & Landsverk, J. L. (2008). Dissociation in foster preschoolers: a replication and assessment study. Journal of Trauma and Dissociation, 9(2), 173–190.

Hulette, A. C., Freyd, J. J., Pears, K. C., Kim, H. K., Fisher, P. A., & Becker-Blease, K. A. (2008). Dissociation and post-traumatic symptomatology in maltreated preschool children. Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma, 1(2), 93–108.

Lau, A. S., Leeb, R. T., English, D., Graham, J. C., Briggs, E. C., Brody, K. E., et al. (2005). What’s in a name? A comparison of methods for classifying predominant type of maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 29, 533–551.

Liotti, G., Solomon, J., & George, C. (1999). Disorganization of attachment as a model for understanding dissociative psychopathology. In: J. Solomon & C. George (eds) Attachment disorganization (pp. 291–317). Guilford Press: New York.

Loewenstein, R. J., & Putnam, F. W. (1990). The clinical phenomenology of males with MPD: a report of 21 cases. Dissociation: Progress in the Dissociative Disorders, 3(3), 135–143.

Lyons-Ruth, K. (2003). Dissociation and the parent–infant dialogue: a longitudinal perspective from attachment research. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 51(3), 883–911.

Macfie, J., Cicchetti, D., & Toth, S. (2001a). The development of dissociation in maltreated preschool children. Development and Psychopathology, 13, 233–254.

Macfie, J., Cicchetti, D., & Toth, S. (2001b). Dissociation in maltreated versus nonmaltreated preschoolers. Child Abuse and Neglect, 25, 1253–1267.

Manly, J. T., Cicchetti, D., & Barnett, D. (1994). The impact of subtype, frequency, chronicity, and severity of child maltreatment on social competence and behavior problems. Development and Psychopathology, 6, 121–143.

McLewin, L. A., & Muller, R. T. (2006). Childhood trauma, imaginary companions, and the development of pathological dissociation. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 11(5), 531–545.

Messman-Moore, T. (2000). Child sexual abuse and revictimization in the form of adult sexual abuse, adult physical abuse, and adult psychological maltreatment. Journal of interpersonal violence, 15(5), 489–502.

Ogawa, J. R., Sroufe, L. A., Weinfeld, N. S., Carlson, E. A., & Egeland, B. (1997). Development and the fragmented self: Longitudinal study of dissociative symptomatology in a nonclinical sample. Development and Psychopathology, 9, 855–879.

Pears, K. C., Kim, H. K., & Fisher, P. A. (2008). Psychosocial and cognitive functioning of children with specific profiles of maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32, 958–971.

Peterson, G., & Putnam, F. W. (1994). Preliminary results of the field trial of proposed criteria for dissociative disorder of childhood. Dissociation, 7(4), 212–220.

Putnam, F. W. (1997). Dissociation in children and adolescents. New York: Guilford.

Putnam, F. W., & Peterson, G. (1994). Further validation of the child dissociative checklist. Dissociation, 7(4), 204–211.

Putnam, F. W., Guroff, J. J., Silberman, E. K., Barban, L., et al. (1986). The clinical phenomenology of multiple personality disorder: review of 100 recent cases. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 47(6), 285–293.

Putnam, F. W., Helmers, K., & Trickett, P. K. (1993). Development, reliability, and validity of a child dissociation scale. Child Abuse & Neglect, 17(6), 731–741.

Ross, C. A., Anderson, G., Fleisher, W. P., & Norton, G. R. (1991). The frequency of multiple personality disorder among psychiatric inpatients. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 148(12), 1717–1720.

Sandberg, D. (2001). Information processing of an acquaintance rape scenario among high- and low-dissociating college women. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 14(3), 585–603.

Sanders, B. (1992). The imaginary companion experience in multiple personality disorder. Dissociation: Progress in the Dissociative Disorders, 5(3), 159–162.

Stone, V. E., Cosmides, L., Tooby, J., Kroll, N., & Knight, R. (2002). Selective impairment of reasoning about social exchange in a patient with bilateral limbic system damage. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 99, 11531–11536.

Thornberry, T. P., Ireland, T. O., & Smith, C. A. (2001). The importance of timing: the varying impact of childhood and adolescent maltreatment on multiple problem outcomes. Development and Psychopathology, 13, 957–979.

van IJzendoorn, M. H., & Schuengel, C. (1996). The measurement of dissociation in normal and clinical populations: meta-analytic validation of the Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES). Clinical Psychology Review, 16(5), 365–382.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to our participants and colleagues at the University of Oregon and appreciate the support from the Trauma and Oppression Research Fund at the University of Oregon.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hulette, A.C., Kaehler, L.A. & Freyd, J.J. Intergenerational Associations Between Trauma and Dissociation. J Fam Viol 26, 217–225 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-011-9357-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-011-9357-5