Abstract

Intimate partner violence (IPV) and suicidal behavior are major public health problems in the African American community. This study investigated whether or not IPV and suicidal ideation are correlated in urban African American women, and if the IPV–suicidal ideation link is explained by symptoms of depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). With 323 abused African American females, path analysis revealed that: (1) IPV → depressive symptoms → suicidal ideation, and (2) IPV → PTSD symptoms → depressive symptoms → suicidal ideation. When evaluating abused women, depressive and PTSD symptoms and suicidal thoughts must be assessed. Interventions for reducing suicidal behavior in abused, low income African American women should reduce symptoms of depression and PTSD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Both intimate partner violence (IPV) and suicidal behavior are major public health problems for African Americans (Joseph 1997; Poussaint and Alexander 2000; West 2004). Although women from all ethnic backgrounds and socioeconomic levels experience IPV, women who are African American, young, poor, divorced or separated, and residing in urban areas are the most frequent victims (Office of Justice Programs 1998; Rennison and Welchans 2000; Wenzel et al. 2006; West 2004). African American women are the victims in over half the violent deaths of females (Bailey et al. 1997) and homicide by an intimate partner is the leading cause of premature death among African American women ages 15–44 years (National Center for Health Statistics 1997; Office of Justice Programs 1998). IPV takes more violent forms in the African American than Caucasian community (Hampton et al. 2003; Hampton and Gelles 1994; Kessler et al. 2001). Intimate partner femicide and near fatal IPV are major causes of premature death and disabling injuries for African American women (Campbell et al. 2002). African Americans experience these negative physical and mental health sequelae of IPV more often and in more severe forms than their Caucasian counterparts (West 2002).

Among African American females, suicide is a top ten leading cause of death in 15–34 year olds, and a top twenty leading cause for 35–64 year olds (webappa.cdc.gov/cgi-bin/broker.exe). There is a 2.3% lifetime prevalence of attempted suicide among African Americans (Moscicki et al. 1988), and African American women are more likely to attempt suicide (Canetto and Lester 1995; Chance et al. 1998; Juon and Ensminger 1997) and report suicidal ideation (O'Donnell et al. 2004) than their male counterparts. One particularly negative sequelae of IPV in African Americans is suicide attempts (Kaslow et al. 1998, 2000, 2002; Thompson et al. 2002). African American suicide attempters are more likely than their Caucasian counterparts to have a history of IPV (Stark and Flitcraft 1996). Further, both depressive and PTSD symptoms are risk factors for suicidal behavior for African Americans (Kaslow et al. 2002; Thompson et al. 1999, 2000).

Abused African American women experience more depressive symptoms than their nonabused counterparts (Houry et al. 2005, 2006). These symptoms may be more prominent among African American than European American IPV victims (Caetano and Cunradi 2003). Compared to those who reported no IPV, low-income African American women who endorsed one, two, or three types of IPV were 2.4, 3.1, and 5.9 times, respectively, more likely to report depressive symptoms (Houry et al. 2006). Those who are abused also endorse more PTSD symptoms than those who are nonabused (Thompson et al. 1999, 2000). Depressive and PTSD symptoms often co-occur in abused women (Lipsky et al. 2005; Nixon et al. 2004; Pico-Alfonso et al. 2006; Stein and Kennedy 2001), although no data addressing this comorbidity could be located for African American women. Research shows links among IPV, depressive and/or PTSD symptoms, and suicide attempts. In abused African American women, depression is a risk factor for suicide attempts (Kaslow et al. 2002; Thompson et al. 2002) and PTSD mediates the IPV–suicide attempt link (Thompson et al. 1999).

A burgeoning literature links depressive symptoms and suicide attempts, PTSD symptoms and suicide attempts, and depressive symptoms and PTSD in abused African American women. However, no investigators have examined the association between IPV and suicidal ideation in the African American community. Further, the studies examining mediators of the IPV–suicide attempt relation have not used more current statistical approaches, such as path analysis, to examine mediational constructs. Path analysis has the advantage of testing presumed causal relationships in correlational data and offers the possibility of examining alternative models.

Using a sample of women seeking treatment in an emergency department (ED) of a large, urban, public-sector, university-affiliated hospital, this study first examined the correlation between IPV and suicidal ideation to ascertain if this link was present. It was anticipated that such an association would be statistically significant. Path analysis was used to ascertain the role of IPV in relation to depressive symptoms, PTSD symptoms, and suicidal ideation. Specification of the path model was based on theory and results of prior empirical studies (Kline 2005). A path model was postulated in which IPV (an exogenous variable, meaning that its causes are not represented in the model) would lead to depressive symptoms and PTSD symptoms. Given that IPV leads to depressive and PTSD symptoms and that suicidal behavior often occurs in response to this psychological distress, it was predicted that depressive and PTSD symptoms would mediate the association between IPV and suicidal ideation. Thus, the hypothesized model being tested was that (1) IPV would have a direct effect on depressive symptoms and PTSD symptoms, and (2) these two variables in turn would have direct effects on suicidal ideation. To exclude the possibility that other models fit the data equally well, two alternative models were tested.

Method

Sample and Procedures

Data were collected at the ED of a large public hospital and level 1 trauma center in a major southeastern city. Most of the individuals (90%) who receive care at this ED are African American and low-income. The ED treats 105,000 patients per year and is staffed by faculty and residents of two medical schools. The investigation was approved by the university’s institutional review board and the hospital’s research oversight committee.

This study focuses on a subsample of a larger project. This subsample includes only African American women who have data from the first of three time points. For the overall study, all women and men, ages 18–55 years, who sought services in the ED were approached in the waiting room, three days a week for 8 h a day. Exclusion criteria included: an indication of IPV as the chief complaint on the patient registration logs, inability to read English at a fifth grade level, apparent intoxication, acute psychosis, or severe medical illness that compromised the person’s capacity to complete a 20 min survey. Participants were taken to a semi-private booth in the ED waiting room; informed consent was obtained; and they completed study materials using a computer kiosk, a method found helpful in previous IPV screening (Rhodes et al. 2006).

Three thousand and eighty-three (3,083) participants completed the kiosk survey, which asked about demographic data (age, race, gender, relationship status, education level) questions related to IPV, depressive symptoms, PTSD symptoms, and suicidal ideation using validated questionnaires. For this report, 323 African American women were identified who endorsed a history of IPV on a five-item screening tool, the George Washington University Universal Violence Prevention Screening Protocol (UVPSP) (Dutton et al. 1996), which has good predictive validity among African American women (Heron et al. 2003). A response in the affirmative to any of the questions was sufficient for inclusion.

Measures

The predictor variable was IPV severity assessed via the Women’s Experience with Battering (WEB) scale (Smith et al. 1995a). The WEB was developed after using qualitative data gleaned from focus groups with battered women (Smith et al. 1995b) and survey data from abused and nonabused women. It was designed to assess the experiences of battered women related to psychological vulnerability, perceptions of susceptibility to physical and psychological danger, or loss of power and control in relationships (Coker et al. 2000a, b; Smith et al. 1995a, b). The WEB includes 10 items scored on a five-point Likert scale. It has high internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.940 in the current sample), good construct and discriminative validity, and is not correlated with social desirability (Smith et al. 1995a).

The outcome variable is suicidal ideation, evaluated using the 19 item Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (BSS) (Beck et al. 1979; Beck and Steer 1991). The BSS gathers data on attitudes, behaviors, and plans to commit suicide using a three-point Likert scale. Scores range from 0 to 38. The BSS has excellent inter-rater reliability and moderately high internal consistency reliability (α = 0.875 in the current sample), as well as good concurrent, discriminant, and predictive validity.

The two mediating constructs were symptoms of depression and PTSD. The 21 item Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II) (Beck et al. 1996) measures severity of depressive symptoms. Item responses consist of 4 statements reflecting increasing levels of severity for each symptom. Total scores range from 0 to 63. The BDI-II has high internal consistency (α = 0.943 for the current sample), and adequate content, factorial, and discriminative validity (Beck et al. 1996; Dozois et al. 1998). The 17 item Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (PDS) (Foa 1995; Foa et al. 1997) provides an index of symptom severity on three PTSD clusters. It has good reliability (test–retest, internal consistency (α = 0.940 in the current sample)), intercorrelations among symptom scales and total score, validity (convergent, concurrent), and sensitivity and specificity.

Data Analysis

Because path analysis is based on a covariance matrix, zero order correlations were first examined. This information addressed the first objective of ascertaining if IPV and suicidal ideation were correlated. To examine the second study aim, namely the interrelationships between IPV, psychological distress (depressive and PTSD symptoms), and suicidal ideation, path analysis was employed. Path analysis requires that data be normally distributed and similarly scaled. Total scores for the WEB, BDI, PDS, and BSS exhibited a prominent positive skew, with a relatively high frequency of zero scores. To correct for this, a square root transformation was used for the BDI-II and inverse transformations for the WEB, PDS, and BSS. To scale data similarly, we multiplied the transformed scores of the BSS and PDS by 10 and the WEB by 100.

To test the hypothesized model and alternative models, path analyses were conducted using maximum likelihood estimation with LISREL version 8.52 (Joreskog and Sorbom 2002). The goal of these analyses was to examine the direct and indirect effects of IPV on depressive symptoms, PTSD symptoms, and ultimately on suicidal ideation. Path analysis involves estimating presumed causal relations among observed variables (Kline 2005), even though they are often measured cross-sectionally. Several indices (i.e., goodness-of-fit index, normed fit index, root mean square error of approximation, and comparative fit index) were used to assess the fit of each model to the data. To compare hierarchical (nested) models after trimming of the selected model, the chi-square difference test was used. To compare alternative (nonhierarchical) models, the model with the lowest Akaike information criterion (AIC) was selected.

Results

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Sample

Sample demographics are reported in Table 1. Overall, this sample was young (M = 32.9, SD = 11.0), single (72.4%), and had completed high school (74.7%).

Association Between IPV and Suicidal Ideation

To examine the association between IPV and suicidal ideation, a zero order correlation was computed. As predicted, the association between the two variables was statistically significant, r = 0.31, p < 0.001.

Path Analysis of the Hypothesized Model

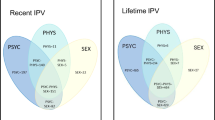

Pearson product-moment coefficients for correlations between study variables are shown in Table 2. All correlations, which ranged from 0.25 (IPV and PTSD symptoms, PTSD symptoms and suicidal ideation) to 0.55 (depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation), were statistically significant (p < 0.001). The modeling process began with the hypothesized path model, shown in Fig. 1. This model included indirect paths of IPV on suicidal ideation through depressive symptoms and PTSD symptoms. All the path coefficients in this model were statistically significant, except for the direct effect of PTSD symptoms on suicidal ideation. All of the fit indices for this initial path model were acceptable (shown in Fig. 1).

Because there was not a direct effect of PTSD symptoms on suicidal ideation, the path between PTSD symptoms and suicidal ideation was trimmed, resulting in the hierarchical model illustrated in Fig. 1. All path coefficients in this model were statistically significant, and the model fit indices remained acceptable. Thus, both the trimmed and original models were viable solutions and showed the same interrelations among variables. Comparing these two hierarchical models resulted in a difference that was not statistically significant, leading to a failure to reject the equal-fit hypothesis. This indicates that the two models have roughly equal fit and therefore the more parsimonious (trimmed) model is preferred. All maximum likelihood parameter estimates (direct, indirect, and total effects) for the trimmed model, as well as variances and disturbances are shown in Table 3.

Conceptually, this model suggests that: (1) IPV has significant direct effects on depressive symptoms and PTSD symptoms, (2) PTSD symptoms have a direct effect on depressive symptoms, (3) depressive symptoms have a direct effect on suicidal ideation, (4) depressive symptoms mediate the IPV–suicidal ideation link, (5) depressive symptoms mediate the PTSD–suicidal ideation link, and (6) PTSD symptoms mediate the IPV–depressive symptom link. Mediation refers to the how, or mechanism by which, a given effect occurs (Baron and Kenny 1986; Holmbeck 1997). In other words, the IPV–suicidal ideation link in African American women may be attributed to depressive symptoms and to PTSD symptoms that lead to depressive symptoms.

Consideration of Alternative Models

Because path analysis does not preclude the possibility that very different models may fit the data equally well, two additional a priori alternative models were considered. We chose two alternative models with psychological distress as the exogenous, or starting, variable that ultimately leads to all other outcomes. In the first alternative model, we proposed that depressive symptoms directly affect IPV and suicidal ideation and that IPV directly affects suicidal behavior and PTSD. As in the trimmed model described above, PTSD symptoms would be driven by IPV. As shown in Fig. 2, the fit indices for this model were not acceptable. The AIC was much higher for this model than for the well-fitting trimmed model, indicating a poor fit relative to the trimmed model above. Therefore, this alternative model did not explain the interrelationships between variables.

In the second alternative model (Fig. 2), it was proposed that PTSD symptoms directly affect suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms. Suicidal ideation also would be influenced by depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation would lead to IPV. However, the fit statistics indicated that this model also was a poor fit for the data. Like the other alternative model, the AIC was much higher for this model than for the well-fitting, trimmed model described above. Therefore, this alternative model was not a satisfactory explanation for the relationships between variables. The failure of these two alternative models offers a statistical basis for choosing the previously described parsimonious model in which IPV impacts depressive and PTSD symptoms, PTSD influences depressive symptoms, and depressive symptoms in turn are associated with higher levels of suicidal ideation.

Discussion

Data gleaned from this study confirm the prediction that there would be a statistically significant link between IPV and suicidal ideation in African American women seeking services in an inner city hospital. This result is consistent with other research showing an association between IPV and suicide attempts in African American women (Kaslow et al. 1998, 2000, 2002; Thompson et al. 2002) and between assault by an intimate partner and suicidal ideation or behavior in a demographically mixed sample (Simon et al. 2002). However, it is the first study to specifically demonstrate an association between IPV and suicidal ideation in African American women. This finding underscores the fact that abused African American women are at increased risk for a range of suicidal behaviors, including ideation and attempts.

The path analysis data shed light on the mechanisms through which this association occurs. The results largely supported our postulated model in which IPV impacted subsequent psychological symptoms (depressive and PTSD), which were in turn associated with suicidal ideation. However, the findings were more complex than anticipated. The IPV → depressive symptoms → suicidal ideation path was as predicted. Namely, abused women with elevated depressive symptoms demonstrated higher levels of suicidal thinking. In other words, IPV presumably caused depressive symptoms, which in turn presumably caused suicidal ideation. However, the role of PTSD was less clear-cut than predicted. It appears that abused African American women develop PTSD symptoms that render them more depressed, which in turn leads them to feel more suicidal. Rejection of the two alternative models provided further support for the specific paths in the postulated model. Our analyses suggest that, in this sample, it is unlikely that depressive symptoms would start the cascade to PTSD via suicidal ideation or IPV, or that PTSD symptoms would have started the cascade that leads to IPV, through depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation.

The powerful role of depression as a mediator is not surprising. Battered women experience more depressive symptoms and disorders than nonabused women (Nixon et al. 2004; Rhodes et al. 2002), with abused women being two to three times more likely to be depressed than women without an IPV history (Sorenson et al. 1996). This is also true for African American women (Houry et al. 2005, 2006). Abused women are likely to feel depressed because being abused is associated with learned helplessness (Walker 2000). The deficits of learned helplessness include low self-esteem, apathy, passivity, and difficulties with problem-solving, attributes often noted in battered women (Campbell et al. 1996; Clements and Sawhney 2000). Battered women also tend to exhibit hopelessness, attributing the cause of the IPV to internal, stable, and global causes and expecting negative outcomes to occur in the future. As a result, they have low self-esteem and dysphoria (Clements and Sawhney 2000). Learned helplessness and hopelessness are associated with developing depressive symptoms (Abramson et al. 1978, 1989) and with suicidality (Abramson et al. 2000). Depressive symptoms and disorders are significant risk factors for suicidal ideation (Goldney et al. 2000). Fortunately, interventions for IPV, such as domestic violence shelters, are associated with reductions in depressive symptoms (Campbell et al. 1995).

The fact that PTSD was not directly related to suicidal ideation in this sample is in keeping with data in which IPV, but not PTSD symptoms, has been found to be a risk factor for suicide attempts (Seedat et al. 2005). PTSD is a common reaction to trauma, such as IPV (Basile et al. 2004; Dutton et al. 2006; Golding 1999; Jones et al. 2001; Lipsky et al. 2005; O'Campo et al. 2006; Pico-Alfonso 2005). However, the symptom constellations of re-experiencing, avoidance, and increased arousal do not necessarily lead individuals to feel suicidal. Rather, these difficulties may result in helplessness and hopelessness associated in the short-term more with depression, which leads to suicidality.

There are several limitations to the present study. First, the sample is relatively homogenous in terms of social class and only one ethnic group is included. Thus, the relevance of the results to women from other racial/ethnic groups or social class backgrounds or to men remains an empirical question. However, this large, homogeneous sample provides enhanced internal validity. African Americans historically have been understudied and the high rates of IPV, particularly severe battering, in African American women (Campbell et al. 2002) and increasing suicide rates within the African Americans community (Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 1998) suggest that continuing research with this population is needed.

A second limitation relates to the fact that although path analysis seeks to understand potential causal relations among variables, correlation does not imply causation. Failure to reject a path model based on its fit indices does not prove that its hypotheses about causality are necessarily correct (Kline 2005). This is particularly true when the data are cross-sectional. Yet, the trimmed postulated model clearly fit the data, whereas the two alternative models did not. Although these two a priori alternative models did not fit the data, other alternative models could be tested.

A third potential weakness is that the variables of interest were measured by self-report. Diagnostic interviews conducted by clinicians were not used and thus depressive and PTSD symptoms, rather than disorders, were assessed. Further, no collateral information was obtained. However, studies have shown that self-report assessments of IPV and mental health problems are reliable and valid (Beck et al. 1979, 1988a, b, 1996, 1997; Beck and Steer 1991; Coker et al. 2000a, b; Cook et al. 2003; Foa 1995; Foa et al. 1993; Hudson and McIntosh 1981; Smith et al. 1995a, b).

A fourth limitation is that the association between IPV and suicidal ideation may be accounted for by variables that were not examined in this study. Other variables found to mediate the IPV–suicide attempt association in African American women, such as substance use and hopelessness, were not studied (Kaslow et al. 1998). Constructs found to moderate this association, such as social support, also were not investigated (Kaslow et al. 1998). Further, additional risk factors for suicidal behavior, such as childhood maltreatment, were not examined (Meadows and Kaslow 2002), nor were factors found to serve a buffering role against suicidal behavior in abused, African American women, including hope, spirituality, self-efficacy, coping, social support, and effectiveness of obtaining resources (Meadows et al. 2005).

Future research could benefit from examining the model supported by this data set with samples of various demographic backgrounds. The inclusion of diagnostic interview data and reports from multiple informants would be of value. Further, more sophisticated models that utilize path analyses to study a larger set of risk factors, as well as protective factors, as mediators of the IPV–suicidal ideation link would be beneficial.

Longitudinal data sets examining these constructs would provide more evidence for causal relationships among the variables. For example, in a longitudinal cohort of New Zealanders, researchers found that psychopathology during adolescence increased the risk of IPV, and IPV in turn increased the risk of adult psychopathology (including depression and PTSD) in female participants (Ehrensaft et al. 2006). Such a longitudinal design suggests that IPV may cause some psychopathology in abused women. Future research may be able to further elucidate the chains suggested in the current paper: IPV → depression and IPV → PTSD → depression.

Despite the aforementioned study limitations, the findings that emerged have a number of key clinical implications. First, it behooves health care and social service professionals evaluating abused African American women to assess their mental health status, with particular attention to symptoms of PTSD, depression, and suicidal ideation. Those abused women found to be depressed may need particular clinical attention. Interventions for abused women should target reducing their symptoms of depression and PTSD using a biopsychosocial framework. These interventions should incorporate state-of-the-art pharmacological interventions for depression and PTSD in conjunction with evidence-based psychosocial interventions for these disorders (American Psychiatric Association 2004; Bradley et al. 2005; Rush 2006; Stein et al. 2006), as well as for IPV and suicidal behavior (American Psychiatric Association 2003; Sullivan 2006). As previous research suggests that women with IPV histories experience more psychopathology than their male counterparts (Ehrensaft et al. 2006), treatment of abused women should be gender-sensitive. All of these interventions also should be conducted in a fashion that is culturally-informed (Heron et al. 1997).

References

Abramson, L. Y., Alloy, L. B., Hogan, M. E., Whitehouse, W. G., Gibb, B. E., Hankin, B. L., et al. (2000). The hopelessness theory of suicidality. In T. Joiner, & M. D. Rudd (Eds.) Suicide science: Expanding the boundaries (pp. 17–32). Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Abramson, L. Y., Metalsky, G. L., & Alloy, L. B. (1989). Hopelessness depression: A theory-based subtype of depression. Psychological Bulletin, 96, 358–372.

Abramson, L. Y., Seligman, M. E. P., & Teasdale, J. (1978). Learned helplessness in humans: Critique and reformulation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 87, 49–74.

American Psychiatric Association (2003). Practice guideline for the assessment and treatment of patients with suicidal behaviors. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(Supplement), 1–60.

American Psychiatric Association (2004). Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(Supplement 11), 1–31.

Bailey, J. E., Kellermann, A. L., Somes, G. W., Banton, J. G., Rivara, F. P., & Rushforth, N. P. (1997). Risk factors for violent death of women in the home. Archives of Internal Medicine, 157, 777–782.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Basile, K. C., Arias, I., Desai, S., & Thompson, M. P. (2004). The differential association of intimate partner physical, sexual, psychological, and stalking violence and posttraumatic stress symptoms in a nationally representative sample of women. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 17, 413–421.

Beck, A. T., Brown, G. K., & Steer, R. A. (1997). Psychometric characteristics of the Scale for Suicide Ideation with psychiatric outpatients. Behavior Research and Therapy, 35, 1039–1046.

Beck, A. T., Kovacs, M., & Weissman, A. (1979). Assessment of suicidal ideation: The Scale for Suicide Ideation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 47, 343–352.

Beck, A. T., & Steer, R. (1991). Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation manual. San Antonio: Harcourt Brace.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). Beck Depression Inventory manual (2nd ed.). San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Garbin, M. G. (1988a). Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review, 8, 77–100.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R., & Ranieri, W. (1988b). Scale for Suicide Ideation: Psychometric properties of a self-report version. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44, 499–505.

Bradley, R. H., Greene, J., Russ, E., Dutra, L., & Westen, D. (2005). A multidimensional meta-analysis of psychotherapy for PTSD. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162, 214–227.

Caetano, R., & Cunradi, C. (2003). Intimate partner violence and depression among Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics. Annals of Epidemiology, 13, 661–665.

Campbell, D. W., Sharps, P. W., Gary, F., Campbell, J. C., & Lopez, L. M. (2002). Intimate partner violence in African American women. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 7.

Campbell, J. C., Kub, J. E., & Rose, L. (1996). Depression in battered women. Journal of the American Medical Women's Association, 51, 106–110.

Campbell, R., Sullivan, C., & Davidson, W. (1995). Women who use domestic violence shelters: Changes in depression over time. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 19, 237–255.

Canetto, S. S., & Lester, D. (1995). Women and suicidal behavior. New York: Springer.

Chance, S. E., Kaslow, N. J., Summerville, M. B., & Wood, K. (1998). Suicidal behavior in African American individuals: Current status and future directions. Cultural Diversity and Mental Health, 4, 19–37.

Clements, C., & Sawhney, D. (2000). Coping with domestic violence: Control attributions, dysphoria, and hopelessness. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 13, 219–240.

Coker, A. L., Smith, P. H., Bethea, L., King, M. R., & McKeown, R. E. (2000a). Physical health consequences of physical and psychological intimate partner violence. Archives of Family Medicine, 9, 451–457.

Coker, A. L., Smith, P. H., McKeown, R. E., & King, M. J. (2000b). Frequency and correlates of intimate partner violence by type: Physical, sexual, and psychological battering. American Journal of Public Health, 90, 553–559.

Cook, S. L., Conrad, L., Bender, M., & Kaslow, N. J. (2003). The internal validity of the Index of Spouse Abuse in African American women. Violence and Victims, 18, 641–657.

Dozois, D. J. A., Dobson, K. S., & Ahnberg, J. L. (1998). A psychometric evaluation of the Beck Depression Inventory-II. Psychological Assessment, 10(2), 83–89.

Dutton, M. A., Green, B. L., Kaltman, S. I., Roesch, D. M., Zeffiro, T. A., & Krause, E. D. (2006). Intimate partner violence, PTSD, and adverse health outcomes. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 21, 955–968.

Dutton, M. A., Mitchell, B., & Haywood, Y. (1996). The emergency department as a violence prevention Center. Journal of the American Medical Women's Association, 51, 92–96.

Ehrensaft, M. K., Moffitt, T. E., & Caspi, A. (2006). Is domestic violence followed by an increased risk of psychiatric disorders among women but not among men? A longitudinal cohort study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163, 885–892.

Foa, E. B. (1995). Posttraumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale: Manual. Minnesota: NCS Pearson Inc.

Foa, E. B., Cashman, L., Jaycox, L. H., & Perry, K. (1997). The validation of a self-report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder: The Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale. Psychological Assessment, 9, 445–451.

Foa, E. B., Riggs, D. S., Dancu, C. V., & Rothbaum, B. O. (1993). Reliability and validity of a brief instrument assessing post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 6, 459–473.

Golding, J. M. (1999). Intimate partner violence as a risk factor for mental disorders: A meta-analysis. Journal of Family Violence, 14, 99–132.

Goldney, R. D., Wilson, D., Dal Grande, E., Fisher, L. J., & McFarlane, A. C. (2000). Suicidal ideation in a random community sample: Attributable risk due to depression and psychosocial and traumatic events. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 34, 98–106.

Hampton, R., Oliver, W., & Magarian, L. (2003). Domestic violence in the African American community: An analysis of social and structural factors. Violence Against Women, 9, 533–557.

Hampton, R. L., & Gelles, R. J. (1994). Violence toward Black women in a nationally representative sample of Black families. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 25, 105–119.

Heron, R. L., Twomey, H. B., Jacobs, D. P., & Kaslow, N. J. (1997). Culturally competent interventions for abused and suicidal African American women. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 34, 410–424.

Heron, S. L., Thompson, M. P., Jackson, E. B., & Kaslow, N. J. (2003). Do responses to an intimate partner violence screen predict scores on a comprehensive measure of intimate partner violence in low-income Black women? Annals of Emergency Medicine, 42, 483–491.

Holmbeck, G. N. (1997). Toward terminological, conceptual, and statistical clarity in the study of mediators and moderators: Examples from the child-clinical and pediatric psychology literatures. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65, 599–610.

Houry, D., Kaslow, N. J., & Thompson, M. P. (2005). Depressive symptoms in women experiencing intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20, 1467–1477.

Houry, D., Kemball, R., Rhodes, K. V., & Kaslow, N. J. (2006). Intimate partner violence and mental health symptoms in African American female ED patients. American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 24, 444–450.

Hudson, W. W., & McIntosh, S. R. (1981). The assessment of spouse abuse: Two quantifiable dimensions. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 43, 873–888.

Jones, L., Hughes, M., & Unterstaller, U. (2001). Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in victims of domestic violence: A review of the research. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 2, 99–119.

Joreskog, K., & Sorbom, D. (2002). The student edition of LSREL 8.52 for windows. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International.

Joseph, J. (1997). Women battering: A comparative analysis of Black and White women. In G. K. Kantor, & J. L. Jasinski (Eds.) Out of the darkness: Contemporary perspectives on family violence (pp. 161–169). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Juon, H. S., & Ensminger, M. E. (1997). Childhood, adolescent, and young adult predictors of suicidal behaviors: A prospective study of African Americans. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38, 553–563.

Kaslow, N. J., Thompson, M., Meadows, L., Chance, S., Puett, R., Hollins, L., et al. (2000). Risk factors for suicide attempts among African American women. Depression and Anxiety, 12, 13–20.

Kaslow, N. J., Thompson, M., Meadows, L., Jacobs, D., Chance, S., Gibb, B., et al. (1998). Factors that mediate and moderate the link between partner abuse and suicidal behavior in African American women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66, 533–540.

Kaslow, N. J., Thompson, M. P., Okun, A., Price, A., Young, S., Bender, M., et al. (2002). Risk and protective factors for suicidal behavior in abused African American women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70, 311–319.

Kessler, R. C., Molnar, B. E., Feurer, I. D., & Appelbaum, M. (2001). Patterns and mental health predictors of domestic violence in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 24, 487–508.

Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford.

Lipsky, S., Field, C. A., Caetano, R., & Larkin, G. L. (2005). Posttraumatic stress disorder symptomatology and comorbid depressive symptoms among abused women referred from emergency department care. Violence and Victims, 20, 645–658.

Meadows, L., & Kaslow, N. J. (2002). Hopelessness as mediator of the link between reports of a history of child maltreatment and suicidality in African American women. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 26, 657–674.

Meadows, L. A., Kaslow, N. J., Thompson, M. P., & Jurkovic, G. J. (2005). Protective factors against suicide attempt risk among African American women experiencing intimate partner violence. American Journal of Community Psychology, 36, 109–121.

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. (1998). Suicide among Black youths, United States, 1980–1995 (No. 47(10)): U.S. Department of Heath and Human Services.

Moscicki, E. K., O’Carroll, P., Rae, D. S., Locke, B. Z., Roy, A., & Regier, D. A. (1988). Suicide attempts in the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, 61, 259–268.

National Center for Health Statistics (1997). Vital statistics mortality data, underlying causes of death, 1979–1995. Hyattsville: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Nixon, R. D., Resick, P. A., & Nishith, P. (2004). An exploration of comorbid depression among female victims of intimate partner violence with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 82, 315–320.

O'Campo, P. J., Kub, J., Woods, A. B., Garza, M., Jones, A. S., Gielen, A. C., et al. (2006). Depression, PTSD, and comorbidity related to intimate partner violence in civilian and military women. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention, 6, 99–110.

O'Donnell, L., O'Donnell, C., Wardlaw, D. M., & Stueve, A. (2004). Risk and resiliency factors influencing suicidality among urban African American and Latino youth. American Journal of Community Psychology, 33, 37–49.

Office of Justice Programs (1998). Bureau of Justice statistics fact book: Violence by intimates - Analysis of data on crime by current or former spouses, boyfriends, and girlfriends (NCJ No. 167237). Washington D.C.: Department of Justice.

Pico-Alfonso, M. A. (2005). Psychological intimate partner violence: The major predictor of posttraumatic stress disorder in abused women. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 29, 181–193.

Pico-Alfonso, M. A., Garcia-Linares, M. I., Celda-Navarro, N., Blasco-Ros, C., Echeburua, E., & Martinez, M. (2006). The impact of physical, psychological, and sexual intimate male partner violence on women's mental health: Depressive symptoms, posttraumatic stress disorder, state anxiety, and suicide. Journal of Women's Health, 15, 599–611.

Poussaint, A. F., & Alexander, A. (2000). Lay my burden down: Unraveling suicide and the mental health crisis among African Americans. Boston: Beacon Press.

Rennison, C. M., & Welchans, S. (2000). Intimate partner violence (No. NCJ-178247). Washington D.C.: Department of Justice.

Rhodes, K. V., Drum, M., Anliker, E., Frankel, R. M., Howes, D. S., & Levinson, W. (2006). Lowering the threshold for discussions of domestic violence: A randomized controlled trial of computer screening. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166, 1107–1114.

Rhodes, K. V., Lauderdale, D. S., He, T., & Howes, D. S. (2002). Between me and the computer: Increased detection of intimate partner violence using a computer questionnaire. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 40, 476–484.

Rush, A. J. (2006). Guidelines for the treatment of major depression. In D. J. Stein, D. J. Kupfer, & A. F. Schatzberg (Eds.) American Psychiatric Publishing textbook of mood disorders (pp. 439–461). Washington D.C.: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Seedat, S., Stein, M. B., & Forde, D. R. (2005). Association between physical partner violence, posttraumatic stress, childhood trauma, and suicide attempts in a community sample of women. Violence and Victims, 20, 87–98.

Simon, T. R., Anderson, M., Thompson, M. P., Crosby, A., & Sacks, J. J. (2002). Assault victimization and suicidal ideation or behavior within a national sample of U.S. adults. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 32, 42–50.

Smith, P. H., Earp, J. A., & DeVellis, R. (1995a). Measuring battering: Development of the Women's Experience with Battering (WEB) Scale. Women's Health, 1, 273–288.

Smith, P. H., Tessaro, I., & Earp, J. A. (1995b). Women’s experiences with battering: A conceptualization from qualitative research. Women's Health Issues, 5, 173–182.

Sorenson, S. B., Upchurch, D. M., & Shen, H. (1996). Violence and injury in marital arguments: Risk patterns and gender differences. American Journal of Public Health, 86, 35–40.

Stark, E., & Flitcraft, A. (1996). Women at risk: Domestic violence and women's health. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Stein, D. J., Kupfer, D. J., & Schatzberg, A. F. (2006). The American Psychiatric Publishing textbook of mood disorders. Washington D.C.: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Stein, M. B., & Kennedy, C. (2001). Major depressive and post-traumatic stress disorder comorbidity in female victims of intimate partner violence. Journal of Affective Disorders, 66, 133–138.

Sullivan, C. M. (2006). Interventions to address intimate partner violence: The current state of the field. In J. R. Lutzker (Ed.) Preventing violence: Research and evidence-based intervention strategies (pp. 195–212). Washington D.C.: American Psychological Association.

Thompson, M. P., Kaslow, N. J., Bradshaw, D., & Kingree, J. B. (2000). Childhood maltreatment, PTSD, and suicidal behavior among African American females. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 15, 3–15.

Thompson, M. P., Kaslow, N. J., & Kingree, J. B. (2002). Risk factors for suicide attempts among African American women experiencing recent intimate partner violence. Violence and Victims, 17, 283–295.

Thompson, M. P., Kaslow, N. J., Kingree, J. B., Puett, R., Thompson, N. J., & Meadows, L. (1999). Partner abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder as risk factors for suicide attempts in a sample of low-income, inner-city women. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 12, 59–72.

Walker, L. E. A. (2000). The battered woman syndrome (2nd edition). New York: Springer.

Wenzel, S. L., Tucker, J. S., Hambarsoomian, K., & Elliott, M. N. (2006). Toward a more comprehensive understanding of violence against impoverished women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 21, 820–839.

West, C. M. (2002). Battered, black and blue: An overview of violence in the lives of Black women. Women & Therapy, 25, 5–27.

West, C. M. (2004). Black women and intimate partner violence: New directions for research. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 19, 1487–1493.

Acknowledgment

This investigation was supported by CDCC R-49 Grant 4230113, “Safety and efficacy of IPV screening for victimization and perpetration.” (Houry—PI, Kaslow—Co-Investigator).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Leiner, A.S., Compton, M.T., Houry, D. et al. Intimate Partner Violence, Psychological Distress, and Suicidality: A Path Model Using Data from African American Women Seeking Care in an Urban Emergency Department. J Fam Viol 23, 473–481 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-008-9174-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-008-9174-7