Abstract

This study examines attitudes towards violence against women among the populace in Moscow, Russia using data drawn from the Moscow Health Survey. Information was obtained from 1,190 subjects (510 men and 680 women) about their perceptions of whether violence against women was a serious problem in contemporary Russia, and under what circumstances they thought it was justifiable for a husband to hit his wife. Less than half the respondents thought violence was a serious problem, while for a small number of interviewees there were several scenarios where violence was regarded as being permissible against a wife. Being young, divorced or widowed, having financial difficulties, and regularly consuming alcohol were associated with attitudes more supportive of violence amongst men; having a low educational level underpinned supportive attitudes among both men and women. Results are discussed in terms of the public reemergence of patriarchal attitudes in Russia in the post-Soviet period.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Intimate partner violence is experienced by a large number of women throughout the world. According to survey estimates, between 10% and 69% of women report having been physically assaulted by a male partner at some point in time (Krug et al. 2002), with the lifetime prevalence of assault ranging between 10–64% in the World Health Organization’s European region (Baumgarten and Sethi 2005). Such violence can result in a number of negative health outcomes that can range from depression and chronic pain to respiratory illnesses, where drug misuse and suicide attempts may also occur in those affected (Krantz 2002). Partner violence against women also frequently precedes fatal outcomes. Indeed, studies from countries as diverse as Australia, Canada, Israel, South Africa, and the United States show that between 40 and 70% of all female murder victims were killed by their intimate partners (Krug et al. 2002). In 2002, over 18,000 females of all ages died as a result of interpersonal violence in Europe (WHO 2006a).

As yet, relatively little is known about the extent of intimate partner violence in the former communist countries in Eastern Europe. This is hardly surprising given the lack of direct statistical data measuring the relationship between the abuser and victim (Johnson 2005). Nevertheless, the few studies which have been conducted suggest that partner violence against women is as common in this region as it is in the rest of Europe. For example, a series of studies in six countries in Eastern Europe and the Caucasus, in the period 1997 to 2001, revealed a lifetime prevalence of physical abuse among ever-married women aged 15–44 ranging from 5% (Georgia) through to 29% (Romania), while between 2–10% of women had been physically abused in the past 12 months (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2003). As regards Russia specifically, the figures were 19% and 6%, respectively—percentages which accord with other studies in the post-Soviet period which have found that, for example, 27% of wives in Moscow had been physically abused by their partner at least once (Cubbins and Vannoy 2005). However, a recent survey of over 1,000 women in seven regions of Russia and the city of Moscow has reported a much higher prevalence of violence as nearly 41% of the women had been hit at least once by their husbands with 27% of them having been beaten repeatedly (Gorshkova and Shurygina 2003).

Alarming as the above figures are, there is reason to believe that they may nonetheless still underestimate the extent of violence against women in contemporary Russia. Although there is evidence that levels of lethal violence have been comparatively high in Russia since at least 1965 (Pridemore 2001), an unprecedented increase in violent mortality has occurred in the transition period (Chervyakov et al. 2002), so much so, that a recent World Health Organization report described violence as a ‘major public health and social threat in the Russian Federation’ (WHO 2005b, p. 24). Thus, even though the majority of victims and perpetrators of violence in Russia have been, and continue to be, men (Johnson 2005), rates of lethal violence against women are still exceptionally high in comparative terms. In 1994, in the ‘peak’ year of violence, the female homicide rate in Russia was nearly 20 times higher than the European Union female average, while in 2004 a rate of 11.66 per 100,000 of the female population was over 40% higher than that in the next nearest country reporting to the World Health Organization in Europe (Kazakhstan—8.20) (WHO 2006b). Accordingly, it has been estimated that a Russian woman is over two times more likely to be killed by her partner than her American counterpart (Gondolf and Shestakov 1997).

Many crimes of violence against women nevertheless continue to go unreported (Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor 2005). In part, this may be because in Russia, domestic violence is often regarded as a family matter by the police who will frequently dismiss cases as a result of either bribery or a failure to believe the victim’s report (Horne 1999). Such behavior may have been reinforced by the emergence of a gender neotraditionalism in recent years which one author has claimed underpins the actions of law enforcement agencies in the post-Soviet period (Johnson 2005). It is possible, however, that there may be another factor, possibly related to this gender neotraditionalism, that may be working to both increase the level of violence against women in Russia as well as reduce its subsequent reporting—the way violence against women is perceived. Several studies from the West have shown that attitudes toward violence against women are one of several factors that may be important in relation to women’s subsequent victimization (Walker 1999). And, many societies throughout the world condone the use of violence against women under specific circumstances and within certain limits of force (Jewkes 2002). Specific events that can trigger such violence can range from a woman refusing to have sex with her partner through to arguing back with him or not obeying him (Krug et al. 2002). Such occurrences threaten the existing balance of power relations between the sexes (Baumgarten and Sethi 2005), which might explain why within many male-dominated societies a violent response is not only thought of as being normative but is even regarded as being ‘just’.

The present study builds on several recent investigations that have examined attitudes toward violence against women in the European Union (European Commission Directorate-General X 1999; Gracia and Herrero 2006), the United States (Straus et al. 1997), and across the world more generally (WHO 2005a) by extending this research to contemporary Russia. As yet, little research has been focused on the extent of the public acceptability of violence against women (Gracia and Herrero 2006). This is particularly true for Russia, although a study from 1995 suggested that violence against women was perceived as being a common occurrence (see Horne 1999), while a more recent study published in Russian has suggested that there may be several circumstances where violence against women is perceived as being legitimate (Gorshkova and Shurygina 2003).

Two aspects of intimate partner violence against women will be examined in the current study. First, we focus on the question of whether violence against women is perceived as being a serious problem in contemporary Russia. Does such a perception vary between the sexes and/or different age groups, and if it does, which factors are associated with this variation? The second part of the study will then examine whether there are specific circumstances in which people think that violence can be legitimately used and examine what factors are associated with justifying the use of violence against women.

This study is extremely apposite in a Russian context, not only because of the high levels of violence against women in Russian society, but also because as Gracia and Herrero (2006) have rightly noted, a social environment supportive of violence against women helps foster a ‘climate of tolerance’ where violence against women is perpetuated. An important first step in any attempt to change this climate is to determine exactly who justifies the use of violence against women, as well as understand the circumstances in which it is thought of as being legitimate, and the particular factors that are associated with these legitimizing attitudes.

Methods

The data in the present study are drawn from the ‘Moscow Health Survey 2004’. This was a collaborative survey undertaken by Swedish and Russian researchers in Moscow in Spring, 2004. A sex and age-stratified random sampling technique was used across the 10 administrative and 125 municipal districts of greater Moscow, with the Moscow city telephone network being used as the sampling frame (98% of flats in Moscow have a telephone). Face-to-face interviews were conducted based on the use of a structured questionnaire. The final sample consisted of 1,190 people aged 18 and above, whose social and demographic characteristics (sex, age, and marital status etc.,) were broadly representative of Moscow’s larger population. The survey response rate was 47%. (For a more detailed description of the sampling methodology and procedure see Vågerö et al. 2008). Each respondent was asked two questions concerning whether they thought violence against women was a serious problem in Russian society and if there were any circumstances (seven scenarios were presented) in which they thought a husband had a good reason to hit his wife. For both questions there were three response alternatives—agree, disagree, and difficult to say.

Binary logistic regression (SPSS 13.0) was used to statistically examine which factors were associated with attitudes to violence against women. Results are presented in the form of odds ratios (OR) with accompanying 95% confidence intervals (CI). For both questions five models were analysed. Model 1 looks at the effects of age, education and marital status on attitudes; in model 2 employment status is added; in model 3 the effects of economic difficulties are examined while in model 4 it is alcohol consumption. Finally, model 5 examines the six variables mentioned above simultaneously. Probability values (p-values) are given underneath each variable in Tables 4 and 5. When these p-values are smaller than 0.05 the association between the variable and the outcome (attitude) is seen as statistically significant, i.e., the association is not due to chance.

Estimates in the final model differed only marginally from those of previous models. Therefore, only the final models are presented in Tables 4 and 5. Results are presented separately for men and women. Tables 2 and 3 contain a direct comparison between the attitudes of men and women, but not adjusted for the above six demographic and social variables. However, an additional analysis of male and female attitudes to violence was undertaken, taking all these variables into account. Results are presented in the text below.

Results

The basic characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1. The age and gender distribution of the respondents are very close to that for Moscow as a whole. The distribution of respondents across the marital status categories differs somewhat between the sexes due to the much larger number of widows rather than widowers (which is explained in part by the alarming rise in mortality among working-age men during the post-Soviet period). The education variable was divided into three categories: those who had a ‘high’ education, which equated to having received a complete or incomplete (university) higher education, those who had a secondary professional or primary professional education were categorized as having a ‘middle’ level of education, while having received a primary, secondary or incomplete secondary education was equated with having a low level of education. As can be seen from Table 1, the majority of respondents (53%) received a high level of education. The extent of this over-sampling depends on the figures one uses for comparative purposes. The Moscow State Statistical Committee (Mosgorkomstat) gives a figure of 45.5% for those aged 15 and over with a high or incomplete higher educational level, while according to data from the 2002 Moscow census (where data for 5% of respondents was not available), this figure was only 35%. This overrepresentation of highly educated respondents and how it may have affected the results will be discussed in more detail later.

Table 1 also reveals that most men are currently working, whereas there is a much more even split for females between the employed and those currently not employed. In addition, almost one-fifth of the sample had to rely on outside financial help during the previous 12 months in order to cover the cost of their regular expenses. In this study, this variable was used as a measure of having experienced financial difficulty, as monetary income has been shown to be a problematic and somewhat unreliable measure when used in contemporary Russia due to such things as receiving alternative forms of non-monetary payment (i.e., payment ‘in kind’). Finally, data were also collected on the frequency of alcohol consumption. The vast majority of both men and women drink one or two times a month or less often, although the percentage of men who drink every day is over eight times greater than it is for women.

Responses to the question ‘Is partner violence against women in Russia today a serious problem?’ are presented in Table 2. There is a large difference between men and women in terms of their perception of this phenomenon. While nearly 53% of women described partner violence against women as a serious problem, only one-third of men did so. It is also interesting to note that there seems to be a fairly even split between the proportion of women who identify partner violence against women as a serious problem and those who reject this notion outright or are unsure (47.1%). Overall, less than half of the sample thought that this issue was a serious problem (44.5%), although only one-seventh (14.4%) rejected the idea totally. Nearly as many people expressed uncertainty about how to describe this phenomenon as those who identified violence as being a problem (41.1% vs. 44.5%). This might indicate that it is an issue that they have given little thought to, or that for many people there are other problems that have assumed more serious proportions in the transition period e.g. impoverishment, corruption, unemployment or the alarming increase in overall crime—including violent crime.

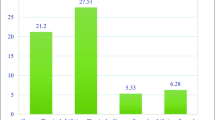

Table 3 lists the percentage of affirmative responses to seven conditions where a ‘man [might] have a good reason to hit his wife’. For the vast majority of both men and women violence is not acceptable in any circumstances. Among those who do agree with its use in some instances, two things are especially noticeable: (1) the large variation in attitudes supportive of the use of violence against a wife among both men and women depending on specific circumstances, and (2) the significantly higher proportion of men who are prepared to justify the use of violence against women under different conditions. With regard to the former, the percentage of men who are prepared to agree with the statement that a man has a good reason to hit his wife ranges from 0.8% (if she asks him about other girlfriends) through to 18.6% (if he finds out that she has been unfaithful). Similarly, among women, the percentages range from 0.4% (she refuses to have sex with him) to 7.4% (where she has been unfaithful). Statistically significant differences in the percentage of men and women agreeing that a man is justified in using violence against his wife were seen in relation to questions concerning unfaithfulness, suspected infidelity, the wife arguing, or failing to complete the housework satisfactorily. Moreover, the fact that there is almost an identical rank ordering by men and women of the situations where violence is thought of a being justified is noteworthy. For both sexes, the issue of infidelity (either actual or suspected) within a marriage is the principal condition where violence against a women is seen as being justified.

In Table 4, the specific variables impacting on the perception of partner violence against women as being a serious problem in Russia were examined. For men, only the more frequent consumption of alcohol seemed to be important—with those men who drink either several times a week or every day being significantly less likely to regard violence against women as a serious problem. In contrast, working-age women are more likely to regard violence against women as being a serious problem than women over the age of 70 although this result was only statistically significant for the 41–50 age group. In addition, having a middle level of education was associated with a woman being more likely to perceive partner violence as a serious problem. Finally, as Table 2 suggested, there was a large difference between men and women in terms of their perception of the seriousness of violence against women. To determine the extent of this difference statistically, the data for men and women were combined and subsequently analyzed in the same model. This showed that women were 2.78 (CI 1.95–3.92; p < 0.000) times more likely to perceive intimate partner violence against women as being a serious problem in Russia (data not shown in table).

In Table 5, factors associated with attitudes supportive of a man being able to hit his wife are presented. As regards the effects of age, there are contrasting results between the sexes. Men aged 18–30 were over 3.5 times more likely to be supportive of a man being able to hit his wife in comparison with men aged over 70. Moreover, men aged 31–40 and 51–60 were also much more likely to justify the use of violence although these latter results were not statistically significant. There were no significant age effects observed for women and the same was true for the differing marital categories. However, men who were divorced or widowed were almost twice as likely to support the idea of a man being able to hit his wife. The effects of education also had a significant impact. Both men and women with a low level of education were over two times more likely to express attitudes supportive of a man being able to hit his wife. There were also significant differences between the sexes with regard to the economic variable examined. While there were no effects seen for women, men who had experienced financial hardship in the previous year were nearly two times more likely to be supportive of male violence. Finally, when controlling for all other variables, men who drink every day are nearly two and a half times more likely to be supportive of a man hitting his wife. Although this result was not statistically significant, this may have been because of the small number of subjects in this particular exposure group. This suggests that the result should be taken as being indicative of a potentially important relation between frequent alcohol consumption among men and attitudes supportive of violence against women.

Discussion

Before going on to discuss the results, it is necessary to focus on the potential limitations of the study. In particular, this relates to the primary response rate among subjects which was 47%. Although this figure is low, it is by no means exceptional either in an international, Russian, or especially a Moscow context. In their study of attitudinal acceptance of intimate partner violence among U.S. adults Simon et al. (2001) had a response rate of 56.1%. With regard to Russia specifically, in Round V of the Russian Longitudinal Monitoring Survey in 1994–1995, while there was an ‘interview completion rate’ of 84.3% for the whole of Russia, the corresponding figure was 56.9% for Moscow (RLMS 2007). Indeed, in a postal survey of Moscow residents in 1991, Palosuo (2000) obtained a response rate of only 29%. When trying to explain why they obtained a response rate of 56% for their Survey of Russian Marriages in Moscow in 1996, Cubbins and Vannoy (2005, p. 40) stated that it was because of ‘Russian fears of crime, and caution in dealing with strangers’. In the current study, an analysis of the reasons for non-response showed that there were a variety of reasons ranging from being unable to establish contact with the potential interviewee through to a physical disability preventing the interview from being conducted. However, most of those who refused to participate gave no specific reason for their refusal. And it is likely that in these circumstances, Cubbins and Vannoy are right that fear of crime may be a motivating factor—especially in a city where the number of registered crimes rose by 2.8 times (from 669 to 1,894 per 100,000 of the population) between 1990 and 2002 (Goskomstat 2003).

Although the survey techniques and sampling procedure employed were methodologically rigorous, there was nevertheless an over-representation of the highly educated among the survey respondents. This may have had contradictory effects, working to inflate the number of people who thought that violence was a serious problem, but at the same time reducing the number who thought that it was justifiable for a man to hit his wife. This being said, our results are similar to those obtained for Moscow recently by Gorshkova and Shurygina (2003) in their survey of attitudes to violence across eight Russian sites.

Taking its lead from Gracia’s recent call for ‘a greater research focus on societal attitudes towards intimate partner violence issues’ (2004, p. 537) this paper has examined two attitudinal aspects of intimate partner violence against women in Moscow, Russia: the question of whether this phenomenon is perceived as a serious problem in contemporary Russia, as well as whether there are specific circumstances in which people think that it is justifiable for a man to hit his wife. In addition, we have also examined if there are any particular demographic and/or socioeconomic variables that may have been important in connection with these specific questions. This research fills an important gap as even though several studies have appeared about violence against women in Russia in recent years, as yet, relatively little is known in the West about the societal attitudes that may be underpinning this violence or about which factors are associated with them.

A third of the men but over half of the women thought that violence against women in contemporary Russia was a serious problem. Making comparisons either over time or between societies is problematic for several reasons, even when the wording of this question does not differ across surveys. Whether this phenomenon is considered alone or in relation to other social problems may affect the respondent’s perception of it; and the base point from which these figures are viewed can also impact on any assessment. For example, the fact that almost half the respondents were ready to identify this issue as a serious problem, even though interpersonal violence against women was regarded as a taboo phenomenon until only very recently in Russia (Rimashevskaya 2005), suggests that the positive assessment that the crisis center movement and the campaign against domestic violence has ‘provided a vocabulary for activists and survivors not only to find a space for their own identities but also to begin to increase public awareness’ (Richter 2002, p. 34) may be correct.

Alternatively, a more negative assessment would highlight the fact that in a society with one of the highest recorded rates of lethal violence against women in the world this figure seems very low, especially when compared with the 83% of respondents who described domestic violence as being either an extremely or very important problem in a survey in the United States in the mid-1990s (Klein et al. 1997), or the 87% of Europeans who when surveyed regarded physical violence against women as being ‘very serious’ (European Commission Directorate-General X 1999). As mentioned above, during the Soviet period, violence against women was regarded as a ‘taboo subject’, in part because of the Soviet authorities refusal to acknowledge the existence of violence more generally in society, but also because familial violence was regarded by many people as being essentially a private matter rather ‘than a widespread social phenomenon’ (Sperling 1990, p. 21). Much the same remains true today where personal information tends to be disclosed to only family and friends (Horne 1999). This continuing lack of openness about the occurrence of domestic violence and Russia’s ‘cultural heritage’, as well as the experience of what has happened in the country in the post-Soviet period, all probably underpin the perception of many people that violence against women is not a serious problem in contemporary Russia.

This situation may have been further exacerbated by the response of the legal authorities who remain skeptical about violence against women (Johnson 2005). As mentioned earlier, this manifests itself in a variety of ways, while insensitive investigation methods also act to discourage women from reporting violence (Horne 1999) as demonstrated by the fact that only 5–8% of the women who contact crisis lines having experienced domestic violence say that they have reported it to the police (Johnson 2005). Moreover, this skepticism also exists at the highest levels of Russian society which probably explains the reason for the absence of reform of the criminal justice statutes concerning domestic violence against women in Russia. Indeed, the lack of change regarding this issue has led Johnson (2005, p. 159) to argue that it signals ‘the continuing ambivalence toward domestic violence at the federal level’.

With regard to support for the use of violence against a wife, as can be seen from Table 3, there are several situations where a man is considered as having a good reason to hit his wife, with sexual infidelity being regarded by both men and women as the principal justifying factor. This has been seen in earlier studies in Russia and from around the world more generally (Gorshkova and Shurygina 2003; Greenblat 1983; Haj-Yahia 2003; WHO 2005a). The percentages recorded in this study seem low when compared with results from similar surveys in other countries (WHO 2005a). However, they are consistent with evidence that support for the use of husband-to-wife violence tends to be both lower in cities (WHO 2005a), and in Moscow than in other parts of Russia (Gorshkova and Shurygina 2003).

Men were much more likely than women to think that a man was justified in using violence in many of the scenarios presented (Table 3). This finding mirrors results from other studies and is not unexpected (Greenblat 1985; Simon et al. 2001). Variables that were important in explaining support for the use of violence included having a low educational level among both sexes, male financial difficulty, divorce and being aged 18–30, while male frequent alcohol use seems to be important for both questions. Although many of these variables have been found to be important in prior research about violence against women in their own right, a more instructive framework for understanding them in contemporary Russia might be in terms of the deteriorating socioeconomic situation that has coincided with a ‘patriarchal–nationalist upsurge that espouses the return of women to the home, and a renewed stress on women’s “natural predestination” as wives and mothers’, in the transition period (Sperling 2000, p. 175).

If education is taken as an example, several earlier studies have shown that both men and women with lower levels of educational attainment are more likely to espouse patriarchal social norms (Ahmad et al. 2004; Smith 1990). Also, those who hold patriarchal beliefs are, in turn, more likely to blame wives for the violence that occurs against them (Haj-Yahia 2003) and view violence against women as being more acceptable (Haj-Yahia 2003; Sakalli 2001). If this link between education and patriarchy does exist in Russia, then it may have been reinforced during the transition period among some men in lower level occupations (with lower levels of education) who have experienced financial problems resulting from such practices as the non-payment, late-payment or ‘payment in kind’ of wages which may have undermined their standing within the home (which stems primarily from their role as the main breadwinner) (Ashwin and Lytkina 2004). For such men, espousing patriarchal norms may be one way to try to reassert their authority. In the present study, this would explain why men with a low level of education, and men who were experiencing financial difficulty, were more likely to be supportive of a husband being able to hit his wife.

The deteriorating social and economic position of some men during the transition period may also have resulted in them turning to alcohol in much the same way as did those men marginalized at work during the Soviet period, where drink and violence were alternative outcomes for those unable to obtain self-realisation at work (Kukhterin 2000). This may explain why, in the current study, both the economically marginalized and frequent drinkers were more supportive of the use of violence, and why those who consumed alcohol more often were less likely to perceive violence against women as a serious problem. However, there may be another reason why males in the 18–30 age group were significantly more supportive of a husband’s right to use violence. According to Kukhterin (2000, p. 85) in the post-Soviet period, the withdrawal of the state has left a space in which ‘a significant section of younger men are attempting to secure a more dominant position in the family’. For some of them, it is possible that one way of obtaining this may be by reverting to a more ‘traditional’ position that may include such things as the belief that a man has a ‘right’ to hit his wife.

Against the appalling background of a substantial rise in lethal violence against both men and women in post-Soviet Russia, the current study has shown that first, violence against women is seen as a serious problem by a majority of women but not men. Second, there are several circumstances in which a small percentage of both men and women think that violence against women is justifiable although the vast majority of both women and men were not supportive of violence under any circumstances. While having a low level of education seems to underpin both male and female attitudes that are supportive of violence, for men, experiencing economic problems and drinking regularly seem to be particularly important. It is possible that such male attitudes may have grown out of, and be underpinned by increased economic hardship during the transition period where the use of violence against women and attitudes supportive of it may have been one possible response in the presence of an emerging gender neo-traditionalism (Johnson 2005). Our findings suggest that despite the fact that the term ‘domestic violence’ has entered the political lexicon in contemporary Russia (Richter 2002), there is still a long way to go before violence against women is regarded as a serious social problem to the same extent as it is in some other societies. However, the importance of this message cannot be understated not least because the way people regard violence can influence such things as victims’ willingness to seek help as well as social policies concerning intimate partner violence (Simon et al. 2001). Moreover, as events in the United States have clearly shown, the way people think about violence against women is not immutable and can change (Klein et al. 1997; Straus et al. 1997).

References

Ahmad, F., Riaz, S., Barata, P., & Stewart, D. E. (2004). Patriarchal beliefs and preceptions of abuse among South Asian immigrant women. Violence Against Women, 10, 262–282.

Ashwin, S., & Lytkina, T. (2004). Men in crisis in Russia: The role of domestic marginalization. Gender & Society, 18, 189–206.

Baumgarten, I., & Sethi, D. (2005). Violence against women in the WHO European region—An overview. Entre Nous: The European Magazine for Sexual and Reproductive Health, 61, 4–7.

Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor (2005). Country reports on human rights practices—Russia 2004. Washington, DC: United States Department of State. Available at: http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/hrrpt/2004/41704.htm.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2003). Reproductive, maternal and child health in Eastern Europe and Eurasia: A comparative report. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Chervyakov, V. V., Shkolnikov, V. M., Pridemore, W. A., & McKee, M. (2002). The changing nature of murder in Russia. Social Science & Medicine, 55, 1713–1724.

Cubbins, L. A., & Vannoy, D. (2005). Socioeconomic resources, gender traditionalism, and wife abuse in urban Russian couples. Journal of Marriage and The Family, 67, 37–52.

European Commission Directorate-General X (1999). Europeans and their views on domestic violence against women. Brussels: European Commission Directorate-General X.

Gondolf, E. W., & Shestakov, D. (1997). Spousal homicide in Russia versus the United States: Preliminary findings and implications. Journal of Family Violence, 12, 63–74.

Gorshkova, I. D., & Shurygina, I. I. (2003). Nasilie nad zhenami v sovremennykh rossiiskikh sem’yakh [Violence against wives in contemporary Russian families]. Moscow: MAKS.

Goskomstat (2003). Regiony Rossii. Osnovnye sotsial’no-ekonomicheskie pokazateli. [Regions of Russia. The main socio-economic indicators]. Moscow: Goskomstat.

Gracia, E. (2004). Unreported cases of domestic violence against women: Towards an epidemiology of social silence, tolerance, and inhibition. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 58, 536–537.

Gracia, E., & Herrero, J. (2006). Acceptability of domestic violence against women in the European Union: A multilevel analysis. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 60, 123–129.

Greenblat, C. S. (1983). A hit is a hit is a hit...or is it? Approval and tolerance of the use of physical force by spouses. In D. Finkelhor, R. J. Gelles, G. T. Hotaling, & M. A. Straus (Eds.) The dark side of families: Current family violence research (pp. 235–260). Beverly Hills: Sage.

Greenblat, C. S. (1985). “Don’t hit your wife...unless...”: Preliminary findings on normative support for the use of physical force by husbands. Victimology: An International Journal, 10, 221–241.

Haj-Yahia, M. M. (2003). Beliefs about wife beating among Arab men from Israel: The influence of their patriarchal ideology. Journal of Family Violence, 18, 193–206.

Horne, S. (1999). Domestic violence in Russia. American Psychologist, 54, 55–61.

Jewkes, R. (2002). Intimate partner violence: Causes and prevention. Lancet, 359, 1423–1429.

Johnson, J. E. (2005). Violence against women in Russia. In W. A. Pridemore (Ed.) Ruling Russia: Law, crime, and justice in a changing society (pp. 147–166). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Klein, E., Campbell, J., Solar, E., & Ghez, M. (1997). Ending domestic violence: Changing public perceptions/halting the epidemic. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Krantz, G. (2002). Violence against women: A global public health issue. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 56, 242–243.

Krug, E. G., Dahlberg, L. L., Mercy, J. A., Zwi, A. B., & Lozano R. (Eds). (2002). World report on violence and health. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Kukhterin, S. (2000). Fathers and patriarchs in communist and post-communist Russia. In S. Ashwin (Ed.) Gender, state and society in Soviet and post-Soviet Russia (pp. 71–89). London: Routledge.

Palosuo, H. (2000). Health-related lifestyles and alienation in Moscow and Helsinki. Social Science & Medicine, 51, 1325–1341.

Pridemore, W. A. (2001). Using newly available homicide data to debunk two myths about violence in an international context: A research note. Homicide Studies, 5, 267–275.

Richter, J. (2002). Promoting civil society? Democracy assistance and Russian women’s organizations. Problems of Post-Communism, 49, 30–41.

Rimashevskaya, N. M. (Ed.), (2005). Razorvat’ krug molchaniya..o nasilii v otnoshenii zhenshchin [Breaking the circle of silence..about violence in relation to women]. Moscow: URSS.

RLMS. (2007). Russian Longitudinal Monitoring Survey. Accessed at: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/rlms/project/samprep.html.

Sakalli, N. (2001). Beliefs about wife beating among Turkish college students: The effects of patriarchy, sexism, and sex differences. Sex Roles, 44, 599–610.

Simon, T. R., Anderson, M., Thompson, M. P., Crosby, A. E., Shelley, G., & Sacks, J. J. (2001). Attitudinal acceptance of intimate partner violence amongst U.S. adults. Violence and Victims, 16, 115–126.

Smith, M. D. (1990). Patriarchal ideology and wife beating: A test of a feminist hypothesis. Violence and Victims, 5, 257–273.

Sperling, V. (1990). Rape and domestic violence in the USSR. Response to the Victimization of Women and Children, 13, 16–22.

Sperling, V. (2000). The ‘new’ sexism: Images of Russian women during the transition. In M. G. Field, & J. L Twigg (Eds.) Russia’s torn safety nets: Health and social welfare during the transition (pp. 173–189). Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Straus, M. A., Kantor, G. K., & Moore, D. W. (1997). Change in cultural norms approving marital violence from 1968 to 1994. In G. K. Kantor, & J. L. Jasinski (Eds.) Out of the darkness: Contemporary perspectives on family violence (pp. 3–16). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Vågerö, D., Kislitsyna, O., Ferlander, S., Migranova, L., Carlson, P., & Rimashevskaya, N. (2008). Moscow Health Survey 2004—Social surveying under difficult conditions. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Walker, L. E. (1999). Psychology and domestic violence around the world. American Psychologist, 54, 21–29.

WHO (2005a). WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women: Initial results on prevalence, health outcomes and women’s responses. Geneva: WHO.

WHO (2005b). Milestones of a global campaign for violence prevention 2005: Changing the face of violence prevention. Geneva: WHO.

WHO (2006a). Injuries and violence in Europe: Why they matter and what can be done. Denmark: WHO.

WHO. (2006b). Health for All Mortality Data Base (HFA-MDB). Available at: http://data.euro.who.int/hfamdb/.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stickley, A., Kislitsyna, O., Timofeeva, I. et al. Attitudes Toward Intimate Partner Violence Against Women in Moscow, Russia. J Fam Viol 23, 447–456 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-008-9170-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-008-9170-y