Abstract

This study examined if mother or child’s perceived social support decreased the emotional and behavioral consequences of intimate partner conflict for 148 African American children ages 8–12. Results revealed that children’s perceived social support mediated the relation between intimate partner conflict and children’s internalizing and externalizing problems. Findings also indicated a mediational role of mother’s perceived social support in the link between both physical and nonphysical partner abuse with children’s internalizing problems. Results from this study suggest that diminished levels of perceived social support associated with intimate partner conflict is a risk factor for psychological problems in children from low-income, African American families. Based on these findings, it is recommended that interventions to address adjustment problems for children exposed to high levels of intimate partner conflict target enhancing the social support of both children and their mothers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is an aggressive conflict management pattern that falls on the negative extreme of a continuum of conflict among intimate partners (Cummings 1998; Danes et al. 2000). This extreme level of intimate partner conflict has a unique relevance to African American women, as these individuals tend to experience violence that is more severe than victims of other races (Joseph 1997; Richie 1996). African American women who live in poverty also have higher rates of IPV than women from other races or social class groups (Campbell and Gary 1998; Neff et al. 1995). Because African American families experience disproportionately high rates of poverty (www.census.gov/hhes/poverty/poverty02), research with low income, African American women and their families targets an especially high risk population.

Exposure to severe intimate partner conflict, such as IPV, can have significant negative effects on children. The consequences of witnessing IPV in childhood include symptoms of depression and anxiety, physical and behavior problems, and proneness to violence perpetration and victimization (Campbell and Lewandowski 1997; Jaffee et al. 2002; Somer and Braunstein 1999). These negative sequelae also have been found among low income, African American children (Kaslow et al. 2003). Two-recent meta-analytic reviews reveal that children exposed to violence in the home experience higher levels of both emotional and behavioral problems (Kitzmann et al. 2003; Wolfe et al. 2003). Finally, the internalizing and externalizing consequences for children exposed to IPV are similar to those of children who have experienced abuse themselves (Jaffe et al. 1986).

Due to the significant psychological consequences of severe intimate partner conflict for children, it is important to consider the role of factors that may help African American families cope with this issue. The potential benefits of social support for individuals from families with high levels of intimate partner conflict have recently received increased attention (Huang and Gunn 2001). Abused women with high levels of social support have fewer negative outcomes than those with little social support (Kaslow et al. 1998; Manetta 1999). Social support plays a central role in the self-efficacy and suicide risk of low-income, abused African American women, such that those women with higher levels of social support feel more efficacious and are less likely to attempt suicide (Thompson et al. 2002).

Experiencing intimate partner conflict that involves violence can diminish the level of social support received by its African American victims (Bender et al. 2003). This may, in part, be a consequence of the heightened control that perpetrators exert over their partners by limiting their social interactions. Violent behavior by a partner also may elicit a negative response from abused women’s social support networks. Abused women’s attempts to obtain help related to IPV may be met with social discomfort and avoidance, leading to diminished self-esteem and mastery (Mitchell and Hodson 1983).

High intensity conflict may also negatively influence children’s peer social support networks. Children who witness IPV may be afraid or forbidden to bring friends to what may be a potentially violent home or they may attend school irregularly (Moore et al. 1990). Another way that children’s extrafamilial social support may be negatively impacted by violence in the home would be if these children were forced to move away from their support system to escape their mothers’ batterers (Beeman 2001).

Exposure to high levels of intimate partner conflict also may affect children’s ability to engage in reciprocal positive peer relationships. Children who have witnessed IPV tend to be more physically and verbally aggressive with peers (Graham-Bermann 1998), and aggressive behavior toward peers increases children’s risk of other peer relationship difficulties (Dodge 1983). Additionally, children whose parents resolve conflict poorly are less involved in activities that could contribute to greater social support, such as prosocial behavior, and are more likely to engage in activities that involve social isolation (Camara and Resnick 1989). If these children also fail to learn skills in negotiation and compromise due to poor conflict resolution modeling by their parents, they may find themselves unable to effectively handle even the most basic conflictual situations with their peers, and this may also lead to social isolation (Camara and Resnick 1989). Finally, children who have witnessed their caregiver be abused tend to experience less empathy than those who have not (Hinchey and Gavelek 1982). This deficit may leave children with difficulties in identifying emotions of others and responding appropriately. Any or all of these challenges may leave children who have witnessed violence between their caregivers at greater risk for developing poor peer relationships.

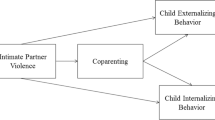

The aforementioned literature highlights ways in which social support may mediate the association between high levels of intimate partner conflict and children’s adjustment. The purpose of the present study is to explore the role of perceived social support as a mediator in the relation between intimate partner conflict and child adjustment problems in a low socioeconomic status (SES) African American sample. The mediator model examined in this investigation suggests that intimate partner conflict is negatively related to both mother and child perceptions of social support and that diminished mother and child perceived levels of social support are associated with poor child adjustment. It is expected that both mother and child perceptions of social support will mediate the relation between intimate partner conflict and child adjustment, and consequently, play an explanatory role in the link between intimate partner conflict and adaptation in African American children from low income families.

Materials and Methods

Participants

The sample consisted of 148 African American women, and their 8–12 year old children. All mothers were the legal guardians of their children. All youth were living with their mother at the time of the assessment and had lived with their mothers at least 50% of the time during the past year. All mothers had been involved with the partner within the past year; however, 95 of the mothers were living with and/or currently married to the partner at the time of assessment and 50 of the mothers were not. The status of three of the mothers’ partners is unknown.

Measures

Child Measures

Children’s Perception of Interparental Conflict Scale (CPIC)

The 48-item CPIC measures the child’s view of interparental conflict. Children respond to each statement by indicating whether it was “true”, “sort of true”, or “false” (Grych et al. 1992). The measure has conflict, blame, and threat scales with acceptable internal consistency and test–retest reliabilities, as well as construct validity. The conflict scale addresses the intensity of interparental conflict. The Blame scale assesses for the extent to which interparental conflict involves child–related issues or the children’s tendency to blame themselves for the conflict. Finally, the threat scales taps into the sense of threat experienced by children in the context of interparental conflict. With the current sample, the internal consistency reliabilities for the conflict, blame, and threat subscales were 0.93, 0.80, and 0.87, respectively.

Social Support Appraisals Scale (SSAS)

This 41-item, 5-point Likert type scale, assesses the child’s appraisals of peer, family, and teacher support, or their sense that they are thought well of and cared about by these sources. The subscales have good internal consistency and test–retest reliabilities (Dubow et al. 1991; Dubow and Ullman 1989). Validity data include moderate to high correlations with other measures of social support and moderate correlations with self-esteem. For the current sample, the internal consistency reliability for the total score of this measure, which was the index used for this study, was α = 0.93.

Youth Self Report (YSR)

The YSR is a 112-item self-report instrument for which youths rate the veracity of each item “now or within the past 6 months” (Achenbach 1991). The instrument provides two broad band dimensions (internalizing, externalizing), which were examined in this study. Scores for the scales were derived by converting raw scores to standard T-scores based on established norms. The YSR has good test–retest reliability in normative samples. The internal consistency reliabilities for this sample were strong, with alphas of 0.89 and 0.86 for the internalizing and externalizing subscales, respectively. Additionally, internal consistency reliability estimates for children in the sample aged 8–10 were also examined since the YSR was originally intended for children aged 11–18. These resulted in alphas of 0.86 and 0.79 for internalizing and externalizing subscales, respectively.

Caregiver Measures

Index of Spouse Abuse (ISA)

The 30–item ISA assesses the presence and severity of physical and nonphysical symptoms of IPV (Hudson and McIntosh 1981). The scale inquires about physical or sexual abuse and emotionally abusive behaviors including psychological threats and coercive tactics. It has good internal consistency, as well as discriminant, content, and construct validity and has been found to be reliable and valid with African American samples (Campbell et al. 1994; Cook et al. 2003; Tolman 2001). For the current sample, the internal consistency reliabilities for the physical and nonphysical abuse subscales were both 0.94.

Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (MOS)

This 18-item, 5-point Likert type self-report questionnaire was originally developed for patients in the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS), a two-year study of patients with chronic conditions (Sherborne and Stewart 1991). It consists of four separate social support subscales “emotional support (also referred to as attachment or affect), informational support (i.e. guidance or appraisal support), tangible support (i.e. material support, aid, reliable alliance), and positive social interaction (similar to the concept of social integration, belonging or social companionship)” (Sherborne and Stewart 1991, p.711) and an overall functional social support index. Higher scores indicate more support. The MOS subscales have good internal consistency and test–retest reliabilities, as well as construct validity. For this study, only the overall functional support index was used; this index had an internal consistency reliability for this sample of 0.96.

Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL)

The CBCL assesses the emotional and behavioral problems of children aged 4–16 according to caregiver report (Achenbach 1991). The measure has 113-items, each of which is scored on a scale of 0–2 and parallels the response format of the YSR. The instrument provides a total behavior problem score, two broad band dimensions (internalizing, externalizing), and several narrow band factors. For this investigation, only the internalizing and externalizing scores were used. Scores for the scales were derived from converting raw scores to standard T-scores on the basis of established norms for the appropriate age and sex groups. The CBCL has good test–retest and inter-rater reliability in normative samples and has been used extensively with low income, ethnic minority samples. The internal consistency reliabilities for this sample were very strong, with alphas of 0.88 and 0.91 for the internalizing and externalizing subscales, respectively.

Procedure

A comprehensive, university-affiliated, public health system in the Southeastern United States that serves a predominantly African American, indigent, urban population served as the setting for this research. Prior to the collection of data, approval for the study was secured from the university’s Institutional Review Board and the hospital’s research oversight committee.

Recruitment

Team members recruited participants by approaching African American women in multiple medical and emergency care clinics in the general hospital and in the associated children’s hospital. Team members also were available 24 h per day to recruit potential participants identified by hospital personnel after seeking services at the health system following an IPV incident. Other recruitment efforts included community outreach to battered women’s shelters and centers and health fairs in the community.

Screening

There were two phases to the screening of study participants. In Stage I, the following inclusion criteria were evaluated by the interviewer: 1) the potential female caregiver participant must have been in a relationship in the past year, 2) the potential female caregiver participant must have an 8–12-year-old child who lived with her at least 50% of the time during the prior year, and 3) the child must have been in contact with the female caregiver’s partner. If these criteria were met and the female caregiver consented, she and her child were scheduled for a 2 1/2–3-h interview.

Stage II of the screening took place at the outset of the interview when brief instruments were used to assess the eligibility of each woman and child. Dyads were excluded if either party was medically unstable or cognitively impaired, or if the mother exhibited significant psychotic symptoms. Responses to the Demographic Questionnaire were used to exclude women and children with life-threatening medical conditions. Cognitive functioning was assessed in the caregivers through the use of the Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) (Folstein et al. 2001) and the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (Williams et al. 1995) and was assessed in the children using the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-III (PPVT-III) (Dunn et al. 1997). Dyads were excluded if mothers had MMSE scores ≤24 if literate or ≤22 if functionally illiterate and/or if children had PVT-III scores <70. A Psychotic Symptom Screening Questionnaire was administered to ascertain those women who were actively psychotic and unable to proceed with the protocol. Dyads excluded after this approximately 20-min screening phase were given $5, transportation costs, and a toy for the child.

Assessment

Caregiver–child dyads meeting inclusion criteria participated in separate, concurrent assessments conducted by research team members (undergraduate and graduate students, and postdoctoral fellows) trained and supervised weekly. Assessments were administered verbally due to the low rates of functional literacy in patients who receive services at the study site (Williams et al. 1995). Upon completion of the large assessment battery, dyads were paid $50. Transportation costs also were covered and the child received a toy.

Results

Sample Descriptives

Means and standard deviations along with frequencies and percentages for background data of participants in this study are reported in Table 1. There were 82 female and 66 male African American child participants. Children ranged in age from 8 to 10 years (M = 10.00, SD = 1.43) and their average grade in school was 4.33 (SD = 1.55). The African American women, aged 22–52 years (M = 32.11, SD = 6.68), were poor as evidenced by the fact that only 51 of the women (35%) were employed. Furthermore, the monthly individual income for the largest percentage of the women (38%) ranged from $500 to $999 and 21 (9.5%) of the women were homeless. Women had an average of 3.43 (SD = 1.82) children, and 4.97 (SD = 2.20) people living in their home.

Mediation

Baron and Kenny’s (1986) recommended pre-requisite criteria for testing mediation were used to determine whether or not statistical mediation should be assessed among study variables. These pre-requisite criteria are that: (1) the predictor must be related to the outcome variable, (2) the predictor must be related to the hypothesized mediator, and (3) the hypothesized mediator must be related to the outcome variable. Statistically significant correlations among study variables (Table 2) were considered to satisfy these pre-requisite criteria. If pre-requisite criteria were met, a z test of indirect paths based on Sobel (1982) was computed to determine if the association between the predictor and the outcome variables was significantly reduced after controlling for the mediator variable. The predictor variable in this study was intimate partner conflict, as reported by child (CPIC) or mother (ISA). The mediator variable was perceived social support as reported by the child (SSAS) or mother (MOS), and the outcome variable was child adjustment as reported by child (YSR) or mother (CBCL). Analyses were conducted either using all measures completed by the child or all measures completed by the mothers.

Child Report

Correlations among child-report variables were examined and, where the pre-requisite criteria for mediation were met, mediational analyses were conducted. These analyses are presented below.

When considering the measures completed by the child-only, Baron and Kenny’s pre-requisite criterion for mediation guided analysis with regards to CPIC conflict measure, SSAS, and YSR internalizing and externalizing symptoms (Baron and Kenny 1986). As depicted in Table 3, Sobel’s test of the indirect effect of CPIC conflict on YSR internalizing problems was statistically significant (z(139) = 2.33, p < 0.05, [beta] = 0.08), suggesting support for the mediational role of children’s perceived levels of social support (SSAS) in the relation between CPIC conflict and YSR internalizing problems. Results from the Sobel’s test of the mediating role of children’s perceived levels of social support (SSAS) in the association between CPIC conflict and YSR externalizing problems were also statistically significant, indicating support for the mediational role of children’s perceived social support (SSAS) in the association between CPIC conflict and YSR externalizing problems (z(139) = 2.15, p < 0.05, [beta] = 0.07).

In terms of CPIC blame as the predictor variable, Sobel analyses indicated support for the mediational role of children’s perceived social support in the relation between CPIC blame and YSR internalizing (z(141) = 2.16, p < 0.05, [beta] = 0.21). However, the correlation between CPIC blame and YSR externalizing problems was not statistically significant (r = 0.18, p > 0.05). Therefore, Sobel analyses examining the mediational role of children’s perceived social support in the relation between CPIC blame and YSR externalizing were not computed.

Support was also found for the mediational role of children’s perceived social support in the link between CPIC threat and YSR internalizing (z(135) = 2.16, p < 0.05, [beta] = 0.10), and in the association between CPIC threat and YSR externalizing (z(135) = 1.94, p = 0.05, [beta] = 0.08). However, it should be noted that the p value found in Sobel analyses examining CPIC threat and YSR externalizing was p = 0.05 rather than p < 0.05 (Table 3).

Taken together, these findings suggest that children’s perceived levels of social support mediate the association between their perceptions of interparental conflict, with regard to the conflict, blame, and threat subscales of the CPIC, and their view of their own internalizing problems. Further, the results indicate that children’s perceptions of their own levels of social support mediate the link between their view of interparental conflict associated with the conflict and threat subscales of the CPIC and their externalizing problems. The findings appear stronger for social support as a mediator of the link between children’s perceptions of interparental conflict and their self-reported internalizing symptoms than for the association between young people’s view of interparental conflict and their own externalizing emotional and behavioral difficulties.

Mother Report

Examination of pre-requisite criteria for mediation among mother-report variables (Table 2) revealed that the correlation between ISA physical and CBCL externalizing problems was not significant (r = 0.16, p > 0.05). Consequently, Sobel analyses examining the mediational role of mother’s perceived levels of social support in the relation between ISA physical and CBCL externalizing problems are not presented. However, pre-requisite criteria for mediation were met for all other mother-report mediational analyses, and these are presented below.

Results from Sobel’s test of indirect effects indicated the effect of ISA physical and CBCL internalizing problems was mediated by maternal social support (MOS) (z(145) = 2.45, p < 0.05, [beta] = 0.04) (Table 4). Sobel’s test of the indirect effect of ISA nonphysical on CBCL internalizing problems was also statistically significant, suggesting support for the mediational role of maternal perceived social support (MOS) in the relation between nonphysical abuse and mother’s report of internalizing problems (z(147) = 1.97, p < 0.05, [beta] = 0.03). However, Sobel analyses did not suggest a mediational role for maternal perceived social support (MOS) in the relation between ISA nonphysical and CBCL externalizing problems (z(147) = 1.02, p = 0.31, [beta] = 0.01). Thus, it appears that maternal view of social support is a key mediator in the link between mothers’ views of their own IPV experiences and their reports of their children’s internalizing, but not their externalizing problems.

Discussion

This study examined the mediational role of perceived social support as experienced by both children and their mothers in the relation between intimate partner conflict and childhood adjustment problems among low-income African American children and their mothers. Findings suggested a mediational role of children’s perceived social support in the relation between child report of intimate partner conflict and both internalizing and externalizing problems. Specifically, children’s perceived social support helped explain the link between the CPIC conflict, blame, and threat subscales with the YSR internalizing and between CPIC conflict and threat and externalizing subscales. Results also revealed that mothers’ perceived social support played a mediational role in the relation between both physical and nonphysical abuse with their children’s internalizing, but not externalizing problems. Therefore, findings from this investigation reveal that diminished levels of perceived social support associated with severe intimate partner conflict is a risk factor for emotional and behavioral problems in children from low-income African American families, and this is particularly true for internalizing difficulties.

These findings are consistent with other research that reveals that children’s perceptions of conflict in the home can affect their risk for adjustment problems. For instance, prior studies have found that the risk for emotional or behavioral problems associated with interparental conflict is affected by the extent to which children perceive the conflict to be threatening to themselves or the security of their family (threat), as well as how responsible they believe themselves to be for the conflict between their caregivers (self-blame) (Grych et al. 2000; Jouriles et al. 2000). Essentially, the emotional and behavioral consequences of interparental conflict are linked to the appraisals that children have about the conflict itself.

This study examined children’s conflict appraisals in three separate domains, as reflected in the CPIC conflict, threat, and self-blame subscales. Our findings indicate that perceived social support had a mediational role in all three of these conflict appraisal domains. Hence, the data suggest that children’s perceived social support plays a mediating role in intimate partner conflict that children perceive to be especially intense (conflict subscale) or threatening (threat subscale), and in conflict for which children believe themselves to have some degree of culpability (blame subscale). Further examination of interparental conflict appraisals as they relate to social support could be helpful in understanding how perceptions of conflict contribute to children’s overall experience of intimate partner conflict as well as the nature of their social support needs.

Additional research could also be helpful in examining one of the primary mother report findings identified in this study. Specifically, it is unclear why perceived social support mediated the relation between mothers’ perceptions of IPV and their children’s internalizing problems, but not their externalizing problems. For example, there is no obvious logic for why the abused, low social support mothers in this study would have been better able to identify negative emotions than undesirable behaviors exhibited by their children. In addition, alternative explanations for this finding are difficult to empirically research because the relation between mothers’ appraisals of their own abuse and their perception of their children’s emotional and behavioral problems has received little attention in the research literature. Therefore, further investigation into the links between maternal perceptions of physical and psychological abuse, perceived levels of social support, and children’s adjustment could be very useful in better understanding this issue.

Several limitations in the interpretation of these study findings deserve consideration. First, the data from this study were collected at one point in time. Therefore, it is not possible to empirically evaluate the direction of relations, as these data are cross-sectional in nature. For example, though it would be unlikely that children’s adjustment problems affected IPV in their home, it is possible that children’s adjustment problems affect the degree of social support that they receive. Further examination of this issue is needed through longitudinal study.

A second limitation is that the measures used to define intimate partner conflict represent slightly different constructs. The CPIC measures a variety of characteristics associated with interparental conflict (conflict, blame, and threat), whereas the ISA specifically measures violence, both physical and nonphysical, among intimate partners. Because children in this study completed the CPIC, they never directly reported on the extent of violence to which they were exposed. It is worth noting that in general, children tend to be aware of violence in their home. For example, research suggests that approximately 80–90% of children from homes with IPV are able to provide detailed descriptions of the violence that occurs in their home, even when their parents believe that they have successfully hidden the violence (Jaffe et al. 1990). However, the extent of violence to which children in this study were exposed was not directly evaluated, and therefore cannot be determined. Future research that uses parallel measures of IPV for both mothers and children in examining the mediating role of perceived social support in the relation between IPV and childhood adjustment could be especially informative to this issue.

Third, the sample used in this study was relatively small. It is possible that formal criteria for statistical significance was not met in analyses examining the role of children’s social support in the link between CPIC threat and YSR externalizing (p < 0.05) due to inadequate statistical power, particularly since findings very closely approached this criteria (p = 0.05). Another limitation was the use of social support measures that examined perceived social support rather than actual receipt of social support. This leaves the possibility that both mother and child’s report of social support were significantly affected by other variables, such as negative emotions.

A fifth limitation is that little information on the mothers’ partners was collected. For example, if data had been gathered on the extent of contact that children had with their mothers’ partners, it would have been possible to examine whether high levels of intimate partner conflict were associated with diminished contact with the mothers’ partners in this study, as found in previous research (Maccoby and Mnookin 1992).

Additionally, whereas the focus on low-income African American mothers and children in this study is an advantage of this investigation, it is also a limitation in that the generalizability of these findings to other races, ethnic groups, and social class groups is unknown. Further, the population examined in this study is comprised of a unique subsample of the African American community, so the respondents who participated in this investigation are not representative of all African American mothers and children. This also potentially reduces the generalizability of the results among African Americans. Therefore, further research of the mediational role of social support in interparental conflict and childhood adjustment should be conducted with other populations, both among other races and within the African-American community.

Finally, further examination of the role of other potential contributory variables in the IPV-child adjustment link may also be helpful in understanding the adjustment of African American children from families who experience IPV. Several of these variables include child physical abuse or maltreatment, child cognitive ability, peer and social relations, and general life stress. Research examining these variables as potential pathways in the link between IPV and child adjustment could help identify the relative contribution of social support in the context of other individual, family, and societal variables.

Despite the aforementioned limitations, taken together, the findings that emerged suggest that perceived social support plays an important role in the adjustment problems of children exposed to high levels of intimate partner conflict. In conjunction with findings from other research (Jouriles et al. 2001), the results of this study suggest a need for increased focus on the social support of both children and their mothers in intervention programs for families who experience high degrees of intimate partner conflict, and IPV in particular. This may entail helping both the mothers and the children develop more effective strategies for communicating and interacting with others; encouraging children to reach out to their peers, teachers, and other supportive adults; supporting mothers in helping their children secure social support; highlighting for mothers the importance of them spending time in supportive relationships with other women, affirming and validating family members, and support people in their communities (e.g., work, religious organizations). It might also be beneficial for these interventions to address the guilt or shame frequently associated with IPV victimization, since these feelings often lead to self-isolating behaviors (Street and Arias 2001).

In summary, findings from this study suggest a mediational role of both mothers’ and children’s perceived social support in the relation between intimate partner conflict and child adjustment in a low-income, African American population. This indicates that perceptions of effective social support among mothers and children may be linked to a reduced risk for adjustment problems in children whose mothers are abused. Therefore, this study supports the need for increased emphasis on interventions that simultaneously target mothers’ and children’s social support in African American families who experience severe intimate partner conflict. These interventions are likely to be most beneficial if they take into account both the disadvantages that challenge low-income African American families as well as the emotional consequences of severe intimate partner conflict on social support.

References

Achenbach, T. M. (1991). Manual for youth self-report and 1991 profile. Burlington: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Beeman, S. K. (2001). Critical issues in research on social networks and social supports of children exposed to domestic violence. In S. A. Graham-Bermann, & J. L. Edleson (Eds.) Domestic violence in the lives of children: The future of research, intervention, and social policy (pp. 219–234). Washington D.C.: American Psychological Association.

Bender, M., Cook, S., & Kaslow, N. J. (2003). Social support as a mediator of revictimization of low-income African American women. Violence and Victims, 18, 419–431.

Camara, K., & Resnick, G. (1989). Styles of conflict resolution and cooperation between divorced parents: Effects on child behavior and adjustment. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 59, 560–575.

Campbell, D. W., Campbell, J., King, C., Parker, B., & Ryan, J. (1994). The reliability and factor structure of the index of spouse abuse with African-American women. Violence and Victims, 9(3), 259–274.

Campbell, D. W., & Gary, F. A. (1998). Providing effective interventions for African American battered women: Afrocentric perspectives. In J. Campbell (Ed.) Empowering survivors of abuse: Health care for battered women and their children (pp. 229–240). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Campbell, J. C., & Lewandowski, L. A. (1997). Mental and physical health effects of intimate partner violence on women and children. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 20, 353–374.

Cook, S. L., Conrad, L., Bender, M., & Kaslow, N. J. (2003). The internal validity of the index of spouse abuse in African American women. Violence and Victims, 18, 641–657.

Cummings, E. M. (1998). Children exposed to marital conflict and violence: Conceptual and theoretical directions. In G. W. Holden, R. Geffner, & E. N. Jouriles (Eds.) Children exposed to marital violence: Theory, research, and intervention (pp. 55–93). Washington D.C.: American Psychological Association.

Danes, S. M., Leichtentritt, R. D., Metz, M. E., & Huddleston-Cases, C. (2000). Effects of conflict styles and conflict severity on quality of life of men and women in family businesses. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 21, 259–286.

Dodge, K. A. (1983). Behavioral antecedents of peer social status. Child Development, 54, 1386–1399.

Dubow, E. F., Tisak, J., Causey, D., Hryshko, A., & Reid, G. (1991). A two-year longitudinal study of stressful life events, social support, and social problem-solving skills: Contributions to children’s behavioral and academic adjustment. Child Development, 62, 583–599.

Dubow, E. F., & Ullman, D. (1989). Assessing social support in elementary school children: The survey of children’s social support. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 18, 52–64.

Dunn, L. M., Dunn, L. M., & Dunn, D. M. (1997). Peabody picture vocabulary test-third edition manual. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E., McHugh, P. R., & Fanjiang, G. (2001). Mini-mental state examination. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Graham-Bermann, S. (1998). The impact of woman abuse on children’s social development: Research and theoretical perspectives. In G. W. Holden, R. Geffner, & E. N. Jouriles (Eds.) Children and marital violence: Theory, research, and intervention (pp. 21–54). Washington D.C.: American Psychological Association.

Grych, J. H., Fincham, F. D., Jouriles, E. N., & McDonald, R. (2000). Interparental conflict and child adjustment: Testing the mediational role of appraisals in the cognitive-contextual framework. Child Development, 71, 1648–1661.

Grych, J. H., Seid, M., & Finchman, F. D. (1992). Assessing marital conflict from the child’s perspective: The children’s perception of interparental conflict scale. Child Development, 63, 558–572.

Hinchey, F. S., & Gavelek, J. R. (1982). Empathic responding in children of battered mothers. Child Abuse and Neglect, 6, 395–401.

Huang, C. J., & Gunn, T. (2001). An examination of domestic violence in an African American community in North Carolina: Causes and consequences. Journal of Black Studies, 31, 790–811.

Hudson, W. W., & McIntosh, S. R. (1981). The assessment of spouse abuse: Two quantifiable dimensions. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 43, 873–888.

Jaffee, S. R., Moffitt, T. E., Caspi, A., Taylor, A., & Arseneault, L. (2002). Influence of adult domestic violence on children’s internalizing and externalizing problems: An environmentally informative twin study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41, 1095–1103.

Jaffe, P., Wolfe, D., & Wilson, S. K. (1990). Children of battered women. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Jaffe, P., Wolfe, D., Wilson, S., & Zak, L. (1986). Similarities in behavioral and social maladjustment among child victims and witnesses to family violence. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 18, 77–90.

Joseph, J. (1997). Women battering: A comparative analysis of black and white women. In G. K. Kantor, & J. L. Jasinski (Eds.) Out of the darkness: Contemporary perspectives on family violence (pp. 161–169). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Jouriles, E. N., McDonald, R., Spiller, L. C., Norwood, W. D., Swank, P. R., & Stephens, N., et al. (2001). Reducing conduct problems among children of battered women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69, 774–785.

Jouriles, E. N., Spiller, L. C., Stephens, N., McDonald, R., & Swank, P. (2000). Variability in adjustment of children of battered women: The role of child appraisals of interparent conflict. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 24, 233–249.

Kaslow, N. J., Heron, S., Roberts, D. K., Thompson, M., Guessous, O., & Jones, C. K. (2003). Family and community factors that predict internalizing and externalizing symptoms in low-income, African American children: A preliminary report. New York Academy of Sciences, 1008, 55–68.

Kaslow, N. J., Thompson, M., Meadows, L., Jacobs, D., Chance, S., & Gibb, B., et al. (1998). Factors that mediate and moderate the link between partner abuse and suicidal behavior in African American women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66, 533–540.

Kitzmann, K. M., Gaylord, N. K., & Kenny, E. D. (2003). Child witness to domestic violence: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 339–352.

Maccoby, E., & Mnookin, R. (1992). Dividing the child. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Manetta, A. A. (1999). Interpersonal violence and suicidal behavior in midlife African American women. Journal of Black Studies, 29, 510–522.

Mitchell, R. E., & Hodson, C. A. (1983). Coping with domestic violence: Social support and psychological health among battered women. American Journal of Community Psychology, 11, 629–654.

Moore, T. E., Pepler, D. J., Weinberg, B., Hammond, L., Waddell, J., & Weiser, L. (1990). Research on children from violent families. Canada’s Mental Health, 38, 19–23.

Neff, J. A., Holamon, B., & Schluter, T. D. (1995). Spousal violence among Anglos, Blacks, and Mexican Americans: The role of demographic variables, psychosocial predictors and alcohol consumption. Journal of Family Violence, 10, 1–21.

Richie, B. E. (1996). Compelled to crime: The gender entrapment of battered Black women. New York: Routledge.

Sherborne, C. D., & Stewart, A. C. (1991). The MOS Social Support Survey. Social Science Medicine, 32, 705–714.

Sobel, M. E. (1982). Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equations models. In S. Leinhart (Ed.) Sociological methodology (pp. 290–312). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Somer, E., & Braunstein, A. (1999). Are children exposed to interparental violence being psychologically maltreated. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 4, 449–456.

Street, A. E., & Arias, I. (2001). Psychological abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder in battered women: Examining the roles of shame and guilt. Violence and Victims, 16, 65–78.

Thompson, M., Kaslow, N. J., Short, L., & Wyckoff, S. (2002). The mediating roles of perceived social support and resources in the self-efficacy-suicide attempts relation among African American abused women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70, 942–949.

Tolman, R. (2001). The validation of the psychological maltreatment of women inventory. In K. D. O’Leary, & R. D. Maiuro (Eds.) Psychological abuse in violent domestic relations (pp. 47–59). New York: Springer.

Williams, M., Parker, R., Baker, D., Parikh, N., Pitkin, K., Coates, W., et al. (1995). Inadequate functional health literacy among patients at two public hospitals. Journal of the American Medical Association, 274, 1677–1682.

Wolfe, D. A., Crooks, C. V., Lee, V., McIntyre-Smith, A., & Jaffe, P. G. (2003). The effects of children’s exposure to domestic violence: A meta-analysis and critique. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 6, 171–187.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

These data are drawn from a study funded by a grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (grant number #R49/CCR419767-0) entitled “Domestic Violence and Child Maltreatment in Black Families” that was awarded to the last author. Correspondence regarding this manuscript should be addressed to Ashley E. Owen, Ph.D., Emory University School of Medicine, Department of Family and Preventive Medicine, The Emory Clinic, 11 Dunwoody Park, Suite 150, Dunwoody GA 30038; Phone: 404-778-6920; aeowen@emory.edu.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Owen, A.E., Thompson, M.P., Mitchell, M.D. et al. Perceived Social Support as a Mediator of the Link Between Intimate Partner Conflict and Child Adjustment. J Fam Viol 23, 221–230 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-007-9145-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-007-9145-4