Abstract

Sibling violence is presumed to be the most common form of family violence and the least studied. Based on data from “Physical Violence in American Families, 1976,” this paper assesses the family environment factors associated with sibling physical violence. Of a range of potential family influences, measures of family disorganization were the most significant predictors of sibling violence, overriding the characteristics of children or particular family demands. What mattered most to the occurrence of sibling violence was a child’s actual experience of physical violence at the hands of a parent, maternal disciplinary practices and whether husbands lose their temper. These findings point to the deleterious effect of corporal punishment, and suggest sibling violence in families is associated with more ominous family and gender dynamics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sibling violence is the least studied form of family violence, but is likely the most prevalent. Straus, Gelles, and Steinmetz (1980) were the first to call attention to sibling violence as a widespread and problematic phenomenon. Based on findings from their survey “Physical Violence in American Families, 1976,” they suggested that the sibling relationship, rather than the husband/wife or parent/child dyad, was the more likely milieu in which a family member might be victimized. When applied to the nation’s estimated 36.3 million children ages 3–17 in their survey year, Straus and Gelles extrapolated that over 29 million American children engage in one or more acts of physical violence toward a sibling (Straus et al., 1980).

Although the prevalence of sibling abuse in childhood has yet to be systematically explored using more recent, representative data, a limited amount of clinical research suggests that sibling violence can be associated with severe emotional and behavioral problems in children (Caffaro & Conn-Caffaro, 1998; Duncan, 1999; Kashani, Daniel, Dandoy, & Holcomb, 1992; Rosenthal & Doherty, 1984). Patterson, Dishion, and Bank (1984) find that boys’ coercive behavior toward a sibling is linked to antisocial behavior among peers and rejection by peers. Similarly, Duncan (1999) finds a significant relationship between peer bullying and sibling bullying, with children who experience both suffering negative emotional consequences.

Some researchers suggest that sibling violence is associated with later negative psychosocial outcomes in adulthood. For example, studies find that childhood sibling violence is associated with later violent behavior in relationships with intimates, peers, and as parents (Gully, Dengerink, Pepping, & Bergstrom, 1981; Loeber, Weissman, & Reid, 1983; Simonelli, Mullis, Elliott, & Pierce, 2002; Steinmetz, 1977). Among clinicians who study adults, sibling violence is thought to have long-lasting and damaging effects on relational ties among adult brothers and sisters (Bank & Kahn, 1982; Caffaro & Conn-Caffaro, 1998; Wiehe, 1997). Several studies also find that sibling violence underlies other emotional and behavioral problems among young adults. For example, Graham-Bermann, Cutler, Litzenberger, and Schwartz (1994) found that women college students who were the earlier target of a sibling’s mild or severe violence exhibited higher rates of anxiety in young adulthood than those who did not. Jensen (1998) reports that young adults, especially males, in her college sample who were perpetrators of sibling abuse, before and after the age of 12, exhibited more frequent drug usage and heavier alcohol consumption.

Despite evidence of its prevalence and long-term effects, and with a few notable exceptions (Felson, 1983; Goodwin & Roscoe, 1990; Hardy, 2001; Simonelli et al., 2002; Wiehe, 1997), few subsequent studies–using either the Straus et al. data or based on new, non-clinical samples–have established the family context of sibling violence, especially those factors that shape sibling violence in relation to broader family violence dynamics. This paper seeks to remedy this neglect by exploring the social characteristics of families in which there is sibling violence and by determining the family environment factors most salient to the occurrence of sibling violence, especially its most egregious forms. This inquiry will contribute both to theoretical and empirical understandings of sibling violence. Further, an exploration of family environment factors associated with sibling violence also helps to better clarify which families are at risk, aiding in early detection and prevention.

This paper also expands our understanding of a consistently understudied family relationship in sociology–that of siblings, either as children or as adults. Because sibling violence is too often dismissed as normal sibling rivalry, we seek to place sibling violence within the context of violent families and within sibling relationships more generally. By placing it along the continuum of family violence behaviors, we aim to de-mythologize sibling violence as innate or inevitable, and to forge a more solid link between the expansive literature on family violence and our still-limited understanding of sibling relationships.

Background

Several researchers have noted that sibling violence is understudied and underreported (DesKeseredy & Ellis, 1997; Stock, 1993; Wiehe, 1997). Sibling violence remains understudied for several reasons. Gelles and Cornell (1985) note that siblings’ hitting each other is so common that few people regard it as deviant behavior. Indeed, they observe that many American parents believe that sibling aggression facilitates their children’s learning how to successfully manage aggressive behavior in future non-family relationships. DesKeseredy and Ellis (1997), drawing from Canadian as well as U.S. research, echo this observation, stating that most find such conflict an inevitable part of sibling relations.

Social norms further encourage expressions of aggressive behavior between siblings. Most of siblings’ aggressive behavior, of course, is thought to be attributable to normal sibling rivalry, something children presumably outgrow and adults inevitably forget. However, research on sibling rivalry is woefully underdeveloped, both as a childhood phenomenon and as a continuing dimension of adult sibling relationships. Its inconsistent operationalization across studies also renders spurious any claims to its universality (Eriksen, 1998). Nevertheless, this notion of siblings as “rivals”–a concept popularized by psychoanalytic theory–continues to drive most discussions of sibling relationships in lay and scholarly circles, minimizing as it does acts of aggression that would otherwise be considered assaults in any other family or personal relationship.

Drawing from clinical practice, Caffaro and Conn-Caffaro (1998) note that sibling rivalry is insufficient to fully explain sibling assault. Rivalry, they argue, includes conflict between siblings that involves possession of something the other also wants, a strengthening of the relationship, and balanced comparisons between siblings. Conversely, assault involves repeated patterns of physical aggression with the intent to harm as well as to humiliate and to defeat. Additionally, they describe sibling assault as part of an escalating pattern of sibling aggression and retaliation unchecked by parental intervention, as well as the solidifying of victim and offender roles between siblings. Such comparisons are not found in research other than that drawn from clinical practice, which leaves unexamined the systematic delineation of differences between sibling rivalry and sibling violence.

Researchers have faced many definitional conundrums with the conceptualization of sibling violence. Some, like Wallace (1996), define sibling abuse as any form of physical, mental or sexual abuse inflicted on one child by another, inclusive of siblings and step-siblings. Noting similar conceptual inconsistencies in the literature on sibling violence, DesKeseredy and Ellis (1997) chose to define sibling violence as “intentional physical violence inflicted by one child in a family unit on another” (p. 399). Stock (1993) suggests that legal definitions contribute to this definition problem, because no specific law protects siblings from other siblings and that such protection can only be obtained when a parent files charges against the abuser on behalf of the victim. In addition, many studies focus on children, leaving mid-to-late adolescence and early adulthood less examined as potential periods of sibling violence. There is also a general tendency in the literature to conflate or use interchangeably such terms as abuse, conflict, aggression and violence (Jensen, 1998).

In the absence of systematic research and conceptualization of sibling violence, especially its family environment correlates, we necessarily borrow from a broad range of studies on family violence, as well as the few focused specifically on sibling violence. From this sparse literature, we find three potential arenas of family influence on sibling violence: socio-demographic and family characteristics; family resources and stability; and family disorganization.

Socio-Demographic and Family Characteristics

Research suggests that age, gender, and family composition are consequential to the occurrence of sibling violence. Age is the more consistent predictor of sibling violence, but its actual configuration of influence remains unclear. Examining younger children, Pepler, Abramovitch, and Corter (1981) found that older siblings (age 4–7) were more likely to initiate aggression, while younger (age 3) siblings tended to either retaliate or submit. Other research suggests that sibling aggression declines with age (Deskeseredy & Ellis, 1997; Steinmetz, 1977; Straus et al., 1980), that siblings tend to fight more with younger siblings than with older (Felson, 1983) and more frequently with those closer in age (DesKeseredy & Ellis, 1997; Felson, 1983; Minnett, Vandell, & Santrock, 1983). Yet, others find no effect of age difference on the occurrence of sibling violence (Abramovitch, Pepler, & Corter, 1982).

Studies also suggest that the gender of the perpetrator and the gender mix of sibling sets are central variables. Among their college-aged subjects, Graham-Bermann et al. (1994) found that their male subjects reported higher levels of violence perpetration, and the sibling dyad at greatest risk involved an older brother perpetrator and a younger sister victim. Goodwin and Roscoe (1990) similarly found among their junior and senior high school students that young men as perpetrators threatened to harm their siblings more often and engaged in a wider range of violent acts (e.g. hitting siblings with objects, holding siblings against their will, beating them up, choking and bodily throwing them), although brothers were as likely recipients of these actions as were sisters. Duncan (1999) also found boys reporting significantly more victimization at the hands of sibling bullies than girls. However, other researchers report no significant difference in the perpetration or victimization of physical violence among male and female siblings (Felson, 1983; Minnett et al., 1983).

Few studies have highlighted directly the effect of family size on the frequency of sibling violence. Hardy (2001) found no significant relationship between number of siblings and sibling violence. Other research on child maltreatment in general reports greater violence by parents toward children among families of larger than average family size (Gil, 1970; Maden & Wrench, 1977; National Research Council, 1993; Wiehe, 1998). Gelles and Straus (1979) find the opposite pattern, however. In their national sample, parents with two children had a higher rate of violence toward their offspring than those with larger families.

Related research also suggests that other family structure variables are implicated in the occurrence of sibling violence. Previous investigators report an association between single-parent families and various forms of family violence like child abuse (Maden & Wrench, 1977). Similarly, others have found that many of the perpetrators of physical abuse in families were not biologically related to the child, suggesting families are more at risk of violence in divorced, separated or blended families (Martin & Walters, 1982; Wiehe, 1998). Direct examination of sibling violence by Hardy (2001) found no significant differences between family composition and sibling violence. However, too few studies have examined the relationship between reconstituted families and sibling violence to establish any pattern.

Thus, while age, gender, and family composition are clearly components of family violence, the ways in which they may augment or diminish sibling violence remains unclear.

Family Resources and Family Stability

Hardy (2001) suggested that the effects of family resources and family stability on sibling violence are gleaned from studies on family violence, rather than sibling violence per se. Studies of family violence suggest socioeconomic status, part-time employment or unemployment, parents’ marriage or divorce, and support networks of kin and community potentially influence violent behavior among siblings.

In general, families who face economic challenges have been shown to have higher rates of family violence. For example, despite the necessary adage that family violence occurs in every social and cultural group, research on family violence in the 1970’s and 1980’s found that both wife abuse and child abuse were more prevalent among families of lower socioeconomic standing (Gelles, 1980; Gelles & Straus, 1979; Straus et al., 1980). Along similar lines, others have found that parents who are unemployed (Gil, 1970; Maden & Wrench, 1977), who are employed part time, especially husbands (Gelles & Straus, 1979), and who report financial problems (Maden & Wrench, 1977) run a greater risk of child abuse. Husbands who report low job satisfaction are also linked with higher rates of wife abuse (Prescott & Letko, 1977). The National Research Council (1993) reported that poverty is strongly associated with child abuse, though the Council report cautions that poverty works within a constellation of factors to increase the likelihood of child abuse. Although some note the possible effect of financial instability on sibling violence (Caffaro & Conn-Caffaro, 1998), only Hardy (2001) has actually found that financial and business stresses, and any work transitions in the family, increase the likelihood of sibling violence.

The absence of stable employment may add to family stress and a family’s social isolation, factors routinely linked with violent families (Gelles, 1980; Wiehe, 1998). Consonant with a family stress model, previous research suggests that abusive families are more socially isolated than non-abusive families (Maden & Wrench, 1977), particularly those families who have lived in the same neighborhood for less than three years or have fewer ties to organizations outside the home (Gelles & Straus, 1979). Indeed, Hardy (2001) found families with high amounts of sibling violence were more isolated, with a rigid boundary created between family and outsiders as a result. Lack of affiliation with, or participation in, religious organizations might be especially important in creating an environment for sibling violence. Research finds that husbands’ religious affiliation and attendance acts as a potential deterrent to wife abuse (Prescott & Letko, 1977).

Family Disorganization

Studies also suggest that sibling violence takes place within a broader context of family violence and disorganization which normalizes aggression among children. Two theoretical models–social learning and family systems theory–suggest, respectively, that children learn how to behave from the actions they see their parents take and that any particular relationship dyad in a family reflects the general tempo and tone of the family constellation as a whole. Taken together, these models direct our attention to the manner in which sibling aggression might mirror, or even be generated by, other forms of violence occurring around children in a family. Within this frame, several forms of family violence appear particularly consequential. Researchers studying the intergenerational transmission of violence among men who batter have noted that witnessing parental violence in childhood may be a more important factor in subsequent male-perpetrated attacks than being the direct target of it (Fagan, Steward, & Hansen, 1983). This would make sense of research that finds a significant relationship between parental use of severe violence to resolve parental conflict and children’s use of severe violence to resolve conflict with each other (Bender, 1953; Graham-Bermann et al., 1994). However, others argue for a more direct effect, citing evidence of children involved in homicidal attacks on younger siblings who were often themselves victims of parental abuse or neglect (Carek & Watson, 1964; Paluszny & McNabb, 1975; Tooley, 1975, cited in Rosenthal & Doherty, 1984). Parallel research reports greater physical and sexual abuse of children from homes in which parent-child conflict was significant (Martin & Walters, 1982). Extant literature in the field of sibling violence that examines the relationship between parental physical abuse of children and sibling violence reaffirms the importance of looking at this particular factor (Caffaro & Conn-Caffaro, 1998; Simonelli et al., 2002).

While both witnessed and actual experience of parental violence are concrete indices of family disorganization, more loosely related factors may also shape levels of sibling violence. For example, research has found that abusive families tend to have higher levels of marital discord and drinking problems (Martin & Walters, 1982), as do abusive husbands (Gelles, 1980). Indeed, Hardy (2001) found that marital strain had a significant impact on sibling violence. Less examined is the relative balance of power between husbands and wives, as well as parents’ orientation toward corporal punishment, as each may shape a particular relational ethos among children that legitimizes aggression based on presumed authority. In this light, studies suggest that abusive parents are particularly prone to believe in spanking (Deley, 1988), and that physical punishment is correlated with increased risk of later adult substance abuse and criminal activity (Straus, 1991). Finally, because the domination-submission relationship assumed by more traditional gender role ideology is strongly associated with family violence (Howell & Pugliesi, 1988), we explore here as well the relationship between adults’ ideas of gender/family equity and the reporting of sibling violence within families.

Taken together, disparate research efforts suggest that individual and family characteristics, family resources and stability, and family disorganization are among the more salient environmental factors that underlie violence among siblings. Our research directly examines the relative effect of these factors on sibling violence.

Method

Sample

We utilized a sub-sample of the 2,143 married couples who were interviewed in Straus and Gelles’ (1976) National Survey of Physical Violence in American Families (NSPVAM). For these analyses, we included survey participants who had two or more children 0–17 years of age.Footnote 1 Although the data set is dated, the 1976 version of this ongoing survey of family violence is the only year in which data on sibling violence were collected. Furthermore, it is the only representative sample of its kind that includes sibling violence. The NSPVAM data, especially the Conflict Tactic Scale, has been consistently critiqued with regard to intimate partner violence, most notably by feminist researchers (see review by Yllo). Nevertheless, these data remain the only large–scale, representative attempt to assess sibling violence and its family violence correlates in a national sample. In addition, aside from preliminary data analyses by the original investigators of the study (Straus et al., 1980), we know of no other systematic effort to analyze the sibling violence data in the manner we do here.

Of the 2,143 respondents in the 1976 survey year, 994 had at least two children living at home. In that survey year, one person from each couple was interviewed about a range of witnessed and experienced family violence, including the amount of directed or initiated aggression by a child randomly selected in the interview protocol (known as the “referent child”).

Others have rightly observed that the decision to focus on one child and from a parent’s point of view, someone who is unlikely to witness every physical altercation between children, resulted in an underestimation of sibling violence in American families (Cappell & Heiner, 1990; Goodwin & Roscoe, 1990). This likely underestimation should be borne in mind in these analyses.

Variables

Dependent variables. The central dependent variable in these analyses concerns the frequency of physical violence among siblings in the past year. Respondents were asked whether or not they had observed the referent child use a range of strategies to resolve conflict in the past year (see appendix for a full itemization of the CTS). Our measure of sibling violence includes only the items on the CTS which represent more serious violence–those actions which run a greater risk of bodily injury. The included CTS items are: threw something at the other one; pushed, grabbed or spanked the other one; kicked, bit or hit with a fist; hit or tried to hit with something; beat up the other one; threatened with a gun or knife; used a knife or gun. Ordinal response options ranged from 1 (not in the past year and not previously, never) to 7 (21 or more times in the past year). Thus, we operationalize sibling violence as physical violence that incurs a risk of injury. Sibling violent or aggressive actions that were verbal or of low injury risk were not included in this study.

Independent variables. We created several independent variables to operationalize socio-demographic and family composition variables. We included both the age and gender of referent child (0 = female; 1 = male). We also included the variable “percent male” (the ratio of male children to all children in the family) to assess the effect of having more male siblings versus less on the frequency of sibling violence. Current family composition is represented by three variables: Children present from a different marriage (0 = no; 1 = yes); referent child’s relationship with respondent (0 = not biological child; 1 = child is biological child), and whether parents are currently separated (0 = no; 1 = yes). Family size is an ordinal scale of how many children 0−17 were currently living at home at the time of the interview (possible range of 2–9 children).

Family resources and family stability include the following indicators. For marital stability and well-being, respondents were asked if they had ever considered separation or divorce (0 = no; 1 = yes), their overall feeling in the marriage (1 = very negative to 7 = very positive), and the number of years married or together. Socio-economic resources were assessed by total family income, with 0 = none to 14 ($35,000), whether or not the husband and the wife were concerned about their financial security, measured separately (1 = not at all to 7 = very concerned), and the educational level of both the husband and the wife (1 = some grade school; 9 = graduate degree). To examine the effect of parental employment status and the availability of parents throughout the working day, we included measures of husband’s and wife’s hourly work week, as well as a measure of whether or not both parents were working full time (1) or were working part time or unemployed (0).

Involvement with kin and community was assessed in a variety of ways. We included measures of the actual years lived in the neighborhood, years lived in the house/apartment, the number of different cities or towns the couple lived in since their marriage, the log of the combined total number of relatives for husband and wife that live within an hour of their residence, and how frequently both the husband and the wife attend religious services (1 = not at all to 5 = weekly).

Finally, for our measures of family disorganization, we created five different scales to assess the effect of witnessed and experienced violence vis a vis parents. Such scales included husband-to-wife violence, wife-to-husband violence, and parent-to-child violence, using the same measures of physical violence itemized on the CTS as we did for sibling violence (see above and Appendix). To better understand how a fractious family environment shapes violence among siblings, we included separate measures of if, or how, frequently the husband or the wife get drunk, each loses his or her temper, or if either starts an argument over nothing, with response categories of 1 (never) to 7 (a lot).

Measures of parental models of punishment include the husband’s use of physical punishment in the past year when the referent child did something wrong (0 = never to 6 = 21 or more times). A measure of the wife’s use of physical punishment is also included. In a similar fashion, we included a measure of the degree to which the respondent believed it was normal or not normal for a parent to slap or spank a twelve-year-old child for a perceived infraction (1 = not normal to 7 = normal), and the degree to which the respondent considered it to be good (range from 1 to 7 with bad = 1 and good = 7). To assess the overall power structure of a family along gender lines, we created a scale that assessed whether a wife or husband should decide only on their own (1), somewhat more on their own (2) or decide equally (3) on the combined six items: buying a car; having children; what house or apartment a family should live in; what job a husband/partner should take; whether or not a wife should go to or quit work; and how much money to spend on food on a weekly basis.

Results

To analyze sibling violence, we used OLS regression to examine a collection of variables that represent socio-demographics/family composition, family resources/ stability and family disorganization. These variables were examined on the subset of cases for which there were two or more children. The analysis proceeded along three pathways. First, sibling physical violence in the past year was regressed on each collection of individual predictors separately. Second, each collection of individual variables was analyzed using stepwise regression in order to determine the most significant predictors of physical sibling violence for each grouping. Finally, we then created a model of all significant indicators for the best possible explanation of sibling violence.

Socio-Demographic and Family Composition: Model I

This set of variables reflects both demographic information about the referent child, the child perpetrating sibling violence, and the basic structure of the family. When sibling physical violence is regressed on these demographic/family composition variables, the age of the referent child is the only significant variable (Table 1). As the age of the child increases, the number of acts of physical violence committed by siblings declines. The variables, collectively, explain a poor but significant 7.8% of the variance in sibling physical violence.

When these variables were subjected to stepwise selection, the age and gender of the referent sibling emerged as the most important factors among these variables. While age decreases the amount of sibling violence, boys were more likely to engage in acts of physical sibling aggression than girls. These two variables were so important in this group that they alone accounted for a significant 7.7% of the variance in sibling violence.

Thus, it is clear that only the demographic characteristics of the referent sibling, and not family structure, are important predictors of sibling violence. However successful age and gender are, they cannot explain fully the phenomenon of physical sibling violence. We now turn to additional familial variables.

Family Resources and Demands: Model II

Next, we examined the variables that represent family resources and family stability for their role in explaining sibling violence. When sibling violence was regressed on this set of variables, we see four predictors attaining statistical significance in this equation (Table 2). The more the couple considered separation or divorce, the greater the amount of sibling violence. Similarly, the more years the couple has been married or together the less sibling violence occurs. There is a significant negative relationship between income of the family and sibling violence; as family income increases, the amount of sibling violence decreases. Notably, the more frequently the religious attendance, the more often physical violence occurs between the children. Two additional variables approached significance. The more that parents worked full time, the less sibling violence (an effect likely similar to family income). Contrary to expectation, the higher the educational level achieved by wives, the more physical violence between siblings. As we saw with the previous set of variables, the family resources/parental demand predictors alone explain a small but significant amount of the variance in sibling physical violence (9.7%).

Stepwise regression added clarity to this emerging model. Both years married or together, and whether a couple considered separation or divorce, persisted as significant predictors for model building. The income of the family maintained its negative relationship with sibling violence. The highest grade level achieved by the wife also remained as a significant element in this model. Together, this four indicator model explains a significant 9.5% of the variance in sibling violence.

In the interest of creating an overall picture of sibling violence, the most significant variables from the demographics/family composition analysis (e.g., age and gender of referent child) were added to this regression (data not shown). The combined regression achieved an adjusted R-square of .158, indicating that we had improved the amount of explained variance by this combined model. Adding these two variables changed several relationships. The income of the family maintains its negative relationship, but the significance is decreased. Those who have considered separation or divorce have children who exhibit greater levels of physical violence. Years married or living together ceases to be significant, indicating that the effect was primarily due to the age of the child and the increased likelihood that couples who were together longer have older children. The wife’s grade level ceases to be significant, but religiosity reemerges as an important predictor.

When these combined variables were subjected to the stepwise selection procedure, four predictors emerged as being the most significant for explaining sibling physical violence. As seen previously, older children are less likely to be physically violent than younger children. Couples who have considered separation or divorce are more likely to have children exhibiting higher levels of sibling violence. Male children are significantly more likely to engage in sibling violence, as are families with lower incomes. Together, these four variables explained an important 16.1% of the variance.

Family Disorganization: Model III

The final set of variables to be examined are the family disorganization variables in Table 3. These variables indicate various forms of family dysfunction or violence-conducive norms including violence between family members, marital problems, alcohol/drug abuse, imbalances of power between husbands and wives, belief in physical punishment of children, and belief in rigid traditional gender roles.

This analysis revealed three significant variables. The amount of parent to child violence in the past year increased the amount of sibling violence dramatically and significantly. This suggests, as has other research, that sibling violence is a larger problem embedded within a context of parental violence. What is interesting, however, is that violence between husbands and wives did not achieve significance. Therefore, the mechanism through which violence is transmitted to siblings is less the observation of it and more the direct experience of physical acts of violence from parent to child. Also significant is physical punishment engaged in by wives. The more that wives as mothers physically punish their children, the more children act aggressively with one another. In a similar fashion perhaps, the more husbands lose their temper, the more violence between children. These latter two variables suggest, too, that it is not witnessed violence but the threat or actual experience of it at the hand of a parent, particularly mothers, that facilitates sibling violence. Combined, the variables in this model accounted for a substantial 34.6% of the variance in sibling violence.

Indeed, the use of stepwise regression on this model yielded the same predictors. Parent to child violence in the past year continues to be a strong and positive factor in sibling abuse. The frequency with which the husband loses his temper is significantly and positively related to sibling violence. These two factors are responsible for all 33.3% of the variance explained by the familial disorganization variables. (Physical punishment by wives remains significant but explains only an additional 1.1% of the total variance.)

Sibling Violence: A Comprehensive Model

By combining the variables included in the stepwise regression models for each grouping of variables, we begin to see the best possible explanation for sibling violence in Table 4.

Sibling violence was regressed on gender and age of the referent child, family income, whether the parents had considered separation or divorce, parent to child violence, the wife’s physical punishment, and the frequency which the husband loses his temper. The result was a model that explained 33.3% of the variance in sibling physical violence, a highly significant model. Parent to child violence was the strongest predictor (Beta = .365) and was highly significant. Physical punishment by wives also significantly increased sibling violence, once other factors were considered, as did husbands’ loss of temper. In this model, male children were also more likely to be physically violent with siblings compared to females. Adding these variables in this model did change the significance of other factors. Age (p=.376), family income (p=.198), and parents’ consideration of separation or divorce (p=.780) ceased to be significant once all factors were considered.

Stepwise selection was applied to this regression model to extract the best possible model from these predictors. Three variables accounted for 33.1% of the explained variance. These were parent to child violence, wives’ physical punishment, and the frequency which the husband lost his temper. Taken together, it appears that the strongest factors in explaining sibling violence are those that relate to the direct experience of physical violence from parent to child, to parental discipline habits and the threat imposed by men’s anger in households. Any real effects of socio-demographic characteristics, family resources, or any other family disorganization may be indirect through direct effects on parents’ physical violence against children and parental coping mechanisms.

Discussion

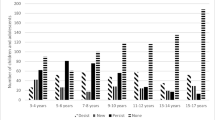

These analyses yield a number of observations about sibling violence. In our initial analyses of socio-demographic and family composition effects on sibling violence, we found that the actual characteristics of the children mattered more than the demographic structure of the household. More specifically, younger children, and to a lesser extent, male children, have a greater likelihood of being violent toward their siblings than their respective counterparts. Age-related patterns in sibling violence were first noted by Straus et al. (1980) when they initially analyzed the data set: they found violence rates decline with each subsequent older age category. Nevertheless, they also pointed out that even among children ages 15–17, two-thirds of them were still engaging in such acts as biting and hitting, often numerous times. In our multivariate analyses, we found that as the age of the child increased, the rates of sibling physical violence declined. This pattern may be, in part, attributable to the physical violence scale we employed, one that included a wide range of actions, from throwing something to using a gun or knife. The less egregious forms (e.g., throwing something) may be more innocuous types of actions typical of younger children, while the life-threatening actions may be a reflection of something more distinct and problematic. Future research might further differentiate severe violence from the less egregious forms to better understand age-related dynamics in the occurrence of sibling violence.

Gender was also initially significant. Numerous observers have noted the role that boys play in aggressive interactions within a range of social relationships, a style of engagement that is a consistent—indeed, expected—part of boys’ earliest socialization experiences. Our findings highlight male childrens’ tendency toward sibling violence, especially in interactions with younger brothers or sisters. These relationships are implicated as a potentially fertile learning environment for subsequent male aggressiveness elsewhere. In this regard, findings by Patterson et al. (1984) that links sibling aggression and antisocial behavior by males in their peer groups is similarly suggestive. This aggression is too often dismissed as innocuous childhood “spats,” or the more proverbial “boys being boys.” But these findings suggest a reconsideration of what boys are learning when acting violently toward siblings, and the role this learning plays in the incidence of male violence in later adolescent and adult relationships. Much of the recent literature on bullying foregrounds the role of boys as bullies (see review by Smith, 2000), but the systematic exploration of sibling relationships as one venue for the development of bullying behavior remains for future research.

In terms of family resources and stability, we found that none of the variables related to parental employment were central to the occurrence of sibling violence (e.g., whether the mother or father, or both, worked full time). These findings suggest that the absence of parents as supervisors to their children may not be as consequential to the violence that occurs between them. However, our measures of parental employment–limited exclusively to hours of work–may disguise the ways that job or hour flexibility, or the type of child care arrangements, shape parental availability and parental intervention.

We did find that our measures of whether parents had considered separation or divorce and their economic resources were central to sibling violence. Research confirms a link between marital discord and child behavior problems (Emery & O'Leary, 1982), as well as anxiety and depression among young adults (Forsstrom-Cohen & Rosenbaum, 1985); our analyses suggest a similar link between marital problems and sibling physical violence. Marital stress may have a ripple effect in and through how children cope with conflict. Along those lines, a longer line of research corroborates the role of socioeconomic resources in the incidence of family violence, especially wife and child abuse (e.g. Kornblit, 1994; Straus et al., 1980). Here, too, the toll of diminished economic resources may be another family stress that exhibits itself in dysfunctional sibling relationships.

We were most intrigued by our measures of family disorganization, especially the effect on sibling violence of parent-to-child violence and the frequency with which husbands lose their temper. The inclusion of a range of family disorganization factors–especially spousal violence, alcohol or drug use, the balance of marital power and gender role ideologies–was partly to assess the role of witnessing family inequities and dysfunction in shaping sibling coping behaviors. Indeed, previous research would suggest that witnessing aggression is central to eventual perpetration of it in intimate relationships, especially male-perpetrated violence (Fagan et al., 1983; Kornblit, 1994). Here, what mattered far more to the frequency of sibling violence was the actual experience of physical violence at the hands of a parent, particularly the mother. In fact, our family disorganization measures were the more significant predictors of sibling violence, overriding the characteristics of children, or particular family demands.

Our analyses suggest that parents’ disciplinary habits and emotional states figure in the level of sibling violence. Indeed, others have found that mothers’ disciplinary behavior toward their children is especially consequential for feelings of family satisfaction among adolescents (e.g. Martin et al., 1987), and behavior problems in children (McLoyd & Smith, 2002), although tentative evidence suggests this pattern may vary by race (Deater-Deckard, Dodge, & Bates, 1996). Being fearful of a father’s temper may also add to the aggressive impulse to physically attack or harm a sibling in response, an elixir that may be especially flammable in families with boys.

Overall, there appears to be a deleterious form of learning taking place among children when parents physically discipline or abuse them. These findings lend tentative support for a growing interrogation of corporal punishment—especially its potential role in fostering an orientation to aggression—occurring among a number of social scientists and family experts (Deley, 1988; Straus, 1994). We would add sibling violence to these emergent concerns as one of the potential consequences of corporal punishment, and urge further research on the effects of both on child well being. These findings also suggest that specific family environment factors, especially parent-to-child violence, maternal disciplinary practices and male intimidation, foster a hostile environment that sibling violence is in part a reflection of.

Our admittedly dated data need current comparisons, both from national samples as well as from more targeted non-clinical populations. Nevertheless, these findings reaffirm our observation that sibling violence remains an understudied phenomenon, but one that is a potential “indicator species” of more ominous family and gender dynamics, and therefore worthy of considerably more research attention.

Notes

The survey asked about children both under the age of 3 as well as those between the ages of 3–17. Most analyses of spouse and child abuse using this data set have analyzed parents with children between the ages of 3–17. Since our focus is on sibling violence, something that could occur even at very young ages, plausibly with older children victimizing even infants, we elected to include parents with two or more children of any age range.

References

Abramovitch, R., Pepler, P., & Corter, C. (1982). Patterns of sibling interaction among preschool age children. In M. E. Lamb & B. Suttondr Smith (Eds.), Sibling relationships: Their nature and significance across the life span (pp. 61–86). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Bank, S. P., & Kahn, M. (1982). The sibling bond. New York: Basic Books.

Bender, L. (1953). Children with homicidal aggression. In L. Bender (Ed.), Aggression, hostility and anxiety in children (pp. 91–115). Springfield, Illinois: Charles C. Thomas.

Caffaro, J., & Conn-Caffaro, A. (1998). Sibling abuse trauma: Assessment and intervention strategies for children, families, and adults. New York: The Haworth Maltreatment and Trauma Press.

Cappell, C., & Heiner, R. (1990). The intergenerational transmission of family aggression. Journal of Family Violence, 5, 135–152.

Carek, D. J., & Watson, A. S. (1964). Treatment of a family involved in fratracide. Archives of General Psychiatry, 11, 533–542.

Deater-Deckard, K., Dodge, K., & Bates, J. E. (1996). Physical discipline among African American and European American mothers: Links to children’s externalizing behaviors. Developmental Psychology, 32, 1065–1072.

Deley, W. (1988). Physical punishment of children: Sweden and the USA. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 19, 419–431.

Doyle, C. (1996). Sexual abuse by siblings: The victim’s perspectives. Journal of Sexaul Aggression, 2, 17–32.

DesKeseredy, W., & Ellis, D. (1997). Sibling violence: A review of Canadian social research and suggestions for further empirical work. Humanity and Society, 21, 397–411.

Duncan, R. (1999). Peer and sibling aggression: An investigation of intra-and etra-familial bullying. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 14, 871–886.

Emery, R. E., & O'Leary, K. D. (1982). Children’s perceptions of marital discord and behavior problems of boys and girls. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 10, 11–24.

Eriksen, S. J. (1998). Sisterhood & brotherhood: An exploration of sibling ties in adult lives. Unpublished dissertation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Amherst, Massachusetts.

Fagan, J. A., Steward, D. & Hansen, K. (1983). Violent men or violent husbands? Background factors and situational correlates. In D. Finkelhor, R. Gelles, G. Hotaling, & M. Straus (Eds.), The dark side of families: Current family violence research (pp. 49–67). Beverly Hills: Sage.

Felson, R. B. (1983). Aggression and violence between siblings. Social Psychology Quarterly, 46, 271–285.

Felson, R. B., & Russo, N. (1988). Parental punishment and sibling aggression. Social Psychology Quarterly, 51, 11–18.

Forsstrom-Cohen, B., & Rosenbaum, A. (1985). The effects of parental marital violence on young adults: An exploratory investigation. Journal of Marriage and Family, 45, 467–472.

Gelles, R. J. (1980). Violence in the family: A review of research in the seventies. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 42, 873–884.

Gelles, R. J. & Cornell, C. P. (1985). Intimate violence in families. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Gelles, R. J., & Straus, M. A. (1979). Violence in the American family. Journal of Social Issues, 35, 15–39.

Gil, D. G. (1970). Violence against children: Physical abuse in the United States. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Goodwin, M. P., & Roscoe, B. (1990). Sibling violence and agnostic interactions among middle adolescents. Adolescence, 25, 451–467.

Graham-Bermann, S. A., Cutler, S., Litzenberger, B., & Schwartz, W. E. (1994). Perceived conflict and violence in childhood sibling relationships and later emotional adjustment. Journal of Family Psychology, 8, 85–97.

Gully, K. J., Dengerink, H. A., Pepping, M., & Bergstrom, D. (1981). Research note: Sibling contribution to violent behavior. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 43, 333–337.

Hardy, M. (2001). Physical aggression and sexual behavior among siblings: A retrospective study. Journal of Family Violence, 16, 255–268.

Howell, M., & Pugliesi, H. (1988). Husbands who harm: Predicting spousal violence by men. Journal of Family Violence, 3, 316–338.

Jensen, V. (1998). Sibling Violence. Paper presented at the Pacific Sociological Association meetings, Portland, Oregon.

Kashani, J. H., Daniel, A. E., Dandoy, A. C., & Holcomb, H. R. (1992). Family violence: Impact on children. Journal of American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry, 31, 181–189.

Kornblit, A. L. (1994). Domestic violence: An emerging health issue. Social Science & Medicine, 9, 1181–1188.

Loeber, R., Weissman, W., & Reid, J. B. (1983). Family interactions of assaultive adolescents, stealers, and non-delinquents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 11, 1–14.

Maden, M. F., & Wrench, D. F. (1977). Significant findings in child abuse research. Victimology, 2, 196–224.

Martin, M. J., & Walters, J. (1982). Family correlates of selected types of child abuse and neglect. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 44, 267–276.

Martin, M. J., Schumm, W. R., Bugaighis, M. A., Jurich, A. P., & Bollman, S. R. (1987). Family violence and adolescents_ perceptions of outcomes of family conflict. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 49, 165–171.

McLoyd, V. C., & Smith, J. (2002). Physical discipline and behavior problems in African American, European American and Hispanic children: Emotional support as a moderator. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 64, 40–53.

Minnett, A. M., Vandell, D. L., & Santrock, J. W. (1983). The effects of sibling status on sibling interaction: Influence of birth order, age, spacing, sex of child and sex of sibling. Child Development, 54, 1064–1072.

National Research Council (1993). Understanding child abuse and neglect. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Paluszny, M., & McNabb, M. (1975). Therapy of a 6-year-old who committed fratracide. Journal of American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 14, 319–336.

Patterson, G. R., Dishion, T. J., & Bank, L. (1984). Family interaction: A process model of deviancy training. Aggressive Behavior, 10, 253–267.

Pepler, D. J., Abramovitch, R., & Corter, C. (1981). Sibling interaction in the home: A longitudinal study. Child Development, 52, 1344–1347.

Prescott, S., & Letko, C. (1977). Battered women: A social psychological perspective. In M. Roy (Ed.), Battered women: A psychosociological study of domestic violence (pp. 72–96). New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Rosenthal, P. A. & Doherty, M. B. (1984). Serious sibling abuse by preschool children. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 23, 186–190.

Simonelli, C., Mullis, T., Elliott, A., & Pierce, T. (2002). Abuse by siblings and subsequent experiences of violence within the dating relationship. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 17, 103–121.

Smith, P. K. (2000). Bullying and harassment in schools and the rights of children. Children & Society, 14, 294–303.

Steinmetz, S. K. (1977). The cycle of violence: Assertive, aggressive, and abusive family interaction. New York: Praeger.

Stock, L. (1993). Sibling abuse: It’s much more serious than child’s play. Children’s Legal Rights Journal, 14, 19–21.

Straus, M. A., Gelles, R. J., & Steinmetz, S. K. (1980). Behind closed doors: Violence in the American family. Garden City, New York: Doubleday.

Straus, M. (1991). Discipline and deviance: Physical punishment of children and violence and other crime in adulthood. Social Problems, 38, 133–154.

Straus, M. (1994). Beating the devil out of them: Corporal punishment in America. Toronto: Macmillan International.

Wallace, H. (1996). Family violence: Legal, medical, and social perspectives. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Wiehe, V. (1998). Understanding family violence: Treating and preventing partner, child, sibling, and elder abuse. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Wiehe, V. (1997). Sibling abuse: Hidden physical, emotional and sexual trauma. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Yllo, K. (1993). Through a feminist lens: Gender, power and violence. In R. Gelles & M. Loeske, (Eds.), (Current controversies on family violence (pp. 47–62). Newbury Park: Sage.

Acknowledgments

A version of this paper was originally presented at the annual meetings of the American Criminological Association, San Francisco, CA, November, 2000.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Eriksen, S., Jensen, V. All in the Family? Family Environment Factors in Sibling Violence. J Fam Viol 21, 497–507 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-006-9048-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-006-9048-9