Abstract

The decision to express a stigmatized identity inside and outside of the workplace is highly complex, with the potential for both negative and positive outcomes. This meta-analysis examines the intrapersonal and interpersonal workplace and non-workplace outcomes of engaging in this identity management strategy. Synthesizing stigma and relationship formation theories, we hypothesize and test boundary conditions for these relationships including the visibility and controllability of the stigma, the study setting, and the gender of the interaction partner. Through our analysis of 65 unique samples (k = 108), we find that expression is more likely to lead to beneficial outcomes in interpersonal, workplace, and non-workplace domains, but only for less-visible stigmas and for studies conducted within a field vs. lab setting. Finally, we explore stigma expression across specific stigmatized identities and determine that there are consistently positive outcomes of expression for individuals with stigmatized religious and sexual orientation identities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The decision of whether, when, where, how, and to whom to express a stigmatized identity is extraordinarily complex. Stigma, defined as a devalued characteristic within a social setting (Goffman, 1963), encompasses a variety of marginalized characteristics, including but not limited to identities based on race, gender, age, religion, sexual orientation, disability status, and certain types of diseases. A great deal of research documents the difficulties associated with having a stigmatized identity, including interpersonal negativity; internal conflict such as stress, life satisfaction, and job commitment; and a variety of negative outcomes that can occur in both social settings, including effects on social support, life satisfaction, positive affect, and stress, and work-related settings, such as workplace anxiety/stress, role ambiguity, job satisfaction, and affective commitment. (e.g., Clair, Beatty, & MacLean, 2005; Fiske, Cuddy, Glick, & Xu, 2002; Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009). As a result, individuals possessing a stigmatized identity must learn how to effectively manage their identities in order to try to minimize the internal turmoil and external backlash that they may experience. A defining experience among stigmatized individuals involves balancing a need to act in socially desirable ways and a need to be authentic in social interactions (Jones & King, 2013).

Previous meta-analyses on self-expression more generally have determined that there are positive interpersonal benefits of revealing information about one’s self, including social support, perceptions of authenticity, and social connections (“self-disclosure;” Collins & Miller, 1994; Frattaroli, 2006). Self-disclosure is typically a positive experience because it allows people to improve connections and form relationships with others and free their minds of unwanted thoughts (Frattaroli, 2006). Expressing, or bringing attention to a stigmatized identity (through disclosing, or expressing an invisible, unknown stigma or through acknowledging, or expressing a visible stigma), however, has much greater potential for undesirable outcomes due to the negative perceptions that society often holds towards these groups. In accordance with stigma theory, expressing a stigmatized group membership reveals that the individual is associated with a group that is devalued by society (Crocker, Major, & Steele, 1998), and this expression can cause one’s status to change from “discreditable” to “discredited” (Goffman, 1963). Thus, expressing a stigma is likely to lead to both positive and negative outcomes.

Indeed, empirical studies have uncovered contradictory findings regarding the outcomes associated with expressing a stigmatized identity to others. Some studies have found that expressing a stigma predicts increased experiences of prejudice and discrimination (e.g., Hebl, Foster, Mannix, & Dovidio, 2002). Other studies, however, have shown that expressing a stigma positively relates to one’s internal psychological outcomes, such as increased life happiness (Beals, Peplau, & Gable, 2009), well-being (Balsam & Mohr, 2007), and job satisfaction (Ragins, Singh, & Cornwell, 2007; Balsam & Mohr, 2007). The current study aims to resolve this discrepant literature by determining whether and under what conditions stigma disclosure is beneficial.

One potential reason for these discrepancies may be the existence of individual and situational boundary conditions that influence the nature of expression outcomes. First, stigmas differ in a number of significant ways, such as their level of visibility, controllability, perceived threat, esthetics, dynamism, and disruptiveness (Jones et al., 1984). Goffman’s (1963) seminal work, as well as current literature (Goodman, 2008; Hebl & Kleck, 2002; Hebl & Skorinko, 2005; Jones & King, 2013) theorize that visibility and perceived controllability of stigmas have the greatest impact on expression outcomes. Accordingly, using the framework of stigma theory, we explore how these two important stigma characteristics moderate outcomes of expression. Second, interactions between stigmatized and non-stigmatized individuals also vary in terms of the contexts in which they take place and the extent to which an interaction partner is accepting of one’s stigma will likely determine whether the expression of that stigma is related to positive or negative intrapersonal and interpersonal outcomes (Griffith & Hebl, 2002). Thus, we examine the moderators of context and recipient gender to assess the influence of one’s environment on expression outcomes. In doing so, this meta-analysis will determine the specific individual and situational factors in which stigma expression is likely to yield positive outcomes.

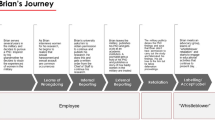

Overall, this meta-analysis study will contribute to existing literature in two significant ways. First, it will help to resolve existing equivocal theories and findings by providing meta-analytic results determining whether expressing a stigma is associated with positive or negative intrapersonal and interpersonal consequences in workplace and non-workplace domains. In doing so, it will provide a direct test of the contradictory assertions proposed by stigma theory and relationship-forming theories. Second, it will explore some of the key boundary conditions that may help to determine the specific situations and characteristics that elicit the most optimal expression outcomes for stigmatized individuals. To begin, we explore the theoretical and empirical evidence regarding the intrapersonal, interpersonal, workplace, and non-workplace outcomes of expressing a stigmatized identity. Then, we examine the boundary conditions that determine the specific situations and characteristics that are more likely to lead to the most optimal outcomes of expressing within each of these four domains. Finally, we provide the meta-analytic results of these relationships and interactions. Thus, this study will provide the first comprehensive test of theoretical assertions regarding whether and when expressing a stigma predicts beneficial outcomes (see Fig. 1).

Outcomes Associated with Stigma Expression

Intrapersonal Outcomes

Research tends to suggest that expressing (compared to suppressing) a stigma produces positive intrapersonal outcomes, such as decreased stress and anxiety and increased life and job satisfaction (Munir, Leka, & Griffiths, 2005; Velez, Moradi, & Brewster, 2013). Alternatively, stigmatized individuals who suppress or avoid talking about their stigmas may develop stress and other negative internal, cognitive outcomes for three primary reasons. First, stigmatized individuals who suppress their identities may create fewer opportunities to attain resources associated with emotional and social support (Sabat et al., 2015). Second, some individuals who suppress must continuously monitor their hidden identities, which can be highly cognitively taxing, especially if they engage in different levels of expression across life domains (Ragins, 2008). Third, individuals who suppress may experience stress due to feelings of inauthenticity (Clair et al., 2005; Goffman, 1963). Individuals are highly motivated to express themselves as complete individuals (Friskopp & Silverstein, 1996) and reach consistency in the way that they and others view themselves (Moorhead, 1999; Swann Jr, 1983). Thus, suppression has the potential to produce a lack of internal self-consistency, thereby eliciting pernicious stress-related outcomes.

Several studies have supported these theoretical assertions. With respect to intrapersonal life outcomes, studies have found that expression is related to decreased psychological stress (Major & Gramzow, 1999) and increased life satisfaction (Beals et al., 2009). Regarding intrapersonal job outcomes, survey studies have found stigma expression to be associated with improved job satisfaction, job commitment, and career commitment and decreased turnover intentions (Ragins & Cornwell, 2001; Ragins et al., 2007). Additionally, a meta-analysis determined that more general experiential disclosures (disclosures about thoughts, feelings, or information about personally meaningful topics) led to various positive health and psychological outcomes (Frattaroli, 2006). Meta-analyses have not yet examined the psychological and health outcomes specific to expressing or information regarding one’s stigmatized identity. However, given these empirical findings, it stands to reason that internal processes will be similar for both types of expression. Thus, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1

Greater levels of expression will be associated with more positive intrapersonal outcomes.

Interpersonal Outcomes

The effects of expressing a stigmatized identity on interpersonal outcomes (such as perceived social support and interpersonal discrimination) are less straightforward. Prior literature theorized that expressing a stigma would be associated with less negative outcomes. Early scholars proposed that stigma expression caused one to be viewed as an out-group member compared to the non-stigmatized majority within a particular context. Thus, expressing was expected to result in social alienation and fewer opportunities for social support (Badgett et al., 2007; Clair et al., 2005; Corrigan & Matthews, 2003; Goffman, 1963). Additionally, according to stigma theory, stigmatized identities are those who are perceived negatively by others (Goffman, 1963). Thus, drawing attention to one’s stigma may elicit negative interpersonal outcomes.

Countering these initial theories, more recent scholarship has uncovered three reasons why stigma expression may be more likely to lead to positive rather than negative interpersonal outcomes. First, communication researchers have theorized that disclosures are one of the primary building blocks in developing positive interpersonal relationships (Collins & Miller, 1994; Miller & Read, 1987), and many of the well-known interpersonal benefits of general self-disclosure are likely to carry over to the expression of stigmas. Second, individuals generally prefer others who reveal information about themselves compared to those who are perceived to be withholding information. To demonstrate, Oswald (2007) found that lesbian and gay male targets who were described in hypothetical vignettes as attempting to suppress their stigmas were rated more negatively compared to those who were described as being expressive about their stigmas. This may be due to the fact that individuals who express their identities are viewed as more authentic, open, and self-affirming compared to those who suppress or conceal their identities (Hebl & Skorinko, 2005). Third, expressing one’s identity may elicit increased social support and social connections. Individuals who express are likely to receive social support from other stigmatized individuals or individuals who are supportive of those stigmas (Beals et al., 2009; Clair et al., 2005; Smith, Rossetto, & Peterson, 2008). Indeed, recent survey research has indicated that expressing a stigma predicts positive interpersonal interactions (Balsam & Mohr, 2007). Thus, we assert that, stigma expression will generally be more likely to lead to positive interpersonal outcomes. These effects may differ depending on other individual and contextual factors that we will consider below.

Hypothesis 2

Greater levels of expression will be associated with more positive interpersonal outcomes.

Workplace Outcomes

Recently, organizational scholars have examined the influence of stigma expression on job-related outcomes, including affective commitment, job stress, job satisfaction, and workplace discrimination. These studies have come to different conclusions about whether expression improves or harms work outcomes for stigmatized employees (Hebl et al., 2002; Ragins & Cornwell, 2001). On the one hand, employees who express their stigmatized identities may make themselves more susceptible to experiences of discrimination and mistreatment (Clair et al., 2005). On the other hand, scholars have identified several ways in which expressing at work is associated with beneficial outcomes. Expressing can allow the stigmatized employee to alleviate workplace anxiety and stress associated with suppressing. This act of workplace suppression can be especially pernicious if the employee discloses to a high degree outside of their workplace (Ragins, 2008). Suppressing can also reduce network ties, team cohesion, and opportunities for mentoring relationships with individuals who share similar interests, values, and identities (Day & Schoenrade, 1997), each of which can negatively impact one’s career advancement (Clair et al., 2005). Relatedly, the act of suppression can cause one to detach and withdraw from one’s organization, ultimately leading to turnover intentions (Ragins et al., 2007). Conversely, expressing one’s stigmatized identity to one’s coworkers and supervisor can elicit improved job satisfaction, especially to the extent that coworkers are supportive of such disclosures (Griffith & Hebl, 2002). Finally, expressing at work may communicate to employers that certain forms of diversity not only exist but also are important to take into consideration when making personnel decisions.

Thus, these expressions may encourage employers to create and promote policies that support these stigmatized individuals within their organizations. Indeed, employers and coworkers will be less likely to provide support in dealing with the barriers associated with these stigmas if they do not believe that the policies would apply to or benefit the employees within their organizations. Thus, expressing at work should be associated with positive outcomes overall, such as decreased job anxiety, decreased role ambiguity, improved job satisfaction, and increased affective commitment (Day & Schoenrade, 1997; Law, Martinez, Ruggs, Hebl, & Akers, 2011). Thus, we expect that:

Hypothesis 3

Greater levels of expression will be associated with positive workplace outcomes.

Non-workplace Outcomes

Lastly, we believe that expressing will be associated with beneficial life outcomes in non-workplace settings, including increased life satisfaction, life stress, positive affect, and perceived social support. Outside of the workplace, individuals will likely have developed strong interpersonal relationships with others that can be significantly harmed or hampered by suppressing or concealing one’s stigma (Pachankis, 2007). Indeed, there is often a social norm of being open about and discussing important parts of one’s identity to one’s friends and family, and individuals who suppress these identities from others outside of the workplace are likely to be viewed as withholding and more interpersonally awkward (Newheiser & Barreto, 2014). In line with this rationale, previous studies have suggested that individuals who express their stigmas outside of the workplace experience increased social support, reduced stress, increased positive affect, and increased life satisfaction (Beals et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2008; Wegner & Lane, 1995). We anticipate that:

Hypothesis 4

Greater levels of expression in non-workplace domains will be associated with more positive life outcomes.

Stigma Characteristics as Moderators

Stigmas differ in a number of important ways that may influence the effectiveness of identity management strategies. According to Jones et al.’s (1984) seminal work, stigmas can be characterized using six different dimensions, including their visibility (the extent to which they are concealable), controllability (whether the stigma was brought on by actions of the individual or by uncontrollable circumstances), threat (the extent to which a stigma is perceived as dangerous), course (the extent to which the stigma changes over time), disruptiveness (the extent to which the stigmatized characteristic impedes social interaction), and esthetics (the extent to which the stigma elicits disgust or negative reactions from others). The majority of work on this topic, however, has focused on two of these characteristics: the visibility of a stigma and perceived controllability of a stigma (Crocker et al., 1998; Goffman, 1963). These two characteristics are thought to have the greatest impact on the outcomes of stigma expression, and thus, we focus on how these characteristics may moderate these expression-outcome relationships.

Visibility of Stigma

Several stigmatized identities are highly visible, such as race, age, gender, height, weight, and certain physical disabilities. In contrast, other stigmas are less visible, and therefore are not typically salient in initial interpersonal interactions. These include religion, sexual orientation, early stages of pregnancy, and certain types of mental or physical disabilities and diseases. The extent to which a stigma is visible to others before an interaction takes place has been a primary focus of expression research (e.g. Goodman, 2008; Jones & King, 2013; Stutterheim et al., 2011a, 2011b). This research has concluded that acknowledging an already-known stigma (such as highlighting one’s race) is associated with negative outcomes, presumably because the individual who expresses an already visible stigma is viewed as overly sensitive or proud of their stigma (Hagiwara, Wessel, & Ryan, 2012).

We believe that expressing an invisible or less-visible stigma should be more impactful and meaningful to others compared to expressions of stigmas that more visible in nature. Because the stigma is unknown prior to disclosure, the expression will not be viewed as a demonstration of pride regarding one’s stigma, but rather a sign of trust or closeness to the recipient. Thus, these forms of expression will be more likely to elicit positive reactions. Additionally, those who suppress a stigma that is highly visible may be less likely to experience intrapersonally negative outcomes due to the implicit assumption that others can already have knowledge about these identities. Those with less visible stigmas may suppress these identities due to fears associated with being “discovered,” an act which has been linked to pernicious stress and health-related outcomes (Meyer, 2003; Sabat et al., 2015). In alignment with this literature, we propose that visibility will moderate the expression-outcome relationships such that these relationships will be more positive for expressions of less visible stigmas and less positive for expressions of highly visible stigmas. Thus, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 5

Perceived visibility will moderate the relationships between expression and (a) intrapersonal, (b) interpersonal, (c) workplace, and (d) non-workplace outcomes, such that these relationships will be positive, especially for stigmas that are less visible.

Perceived Controllability of Stigma

Previous research on stigma expression has also focused a great deal of attention on the degree to which stigmas are perceived as controllable. Indeed, in alignment with stigma theory (Goffman, 1963), stigmas vary in terms of origin, such that they can be present at birth, can be caused accidentally, or can be caused purposefully and deliberately by the target. Indeed, research on the perceived controllability of stigmas has identified several stigmas that are viewed by the general public as highly uncontrollable (such as race, gender, age, and physical disabilities) and several others that are perceived as highly controllable (such as pregnancy, HIV status, and obesity). Stigmas that are thought to be caused by internal, controllable factors are viewed more negatively compared to those that are perceived to be caused by external, uncontrollable factors (Jones & Gordon, 1972). Indeed, people who express or acknowledge a stigma that is viewed as more controllable (obesity) are often treated more negatively compared to those that acknowledge a stigma that is often viewed as less controllable (physical disability; Hebl & Kleck, 2002). Similarly, an experimental study by Hebl and Skorinko (2005) found that manipulating the perceived controllability of the same stigma had a profound impact on interpersonal ratings, such that describing the physical disability as caused by factors outside of the person’s control led to more favorable ratings, whereas suggesting that the disability was caused by the target’s own carelessness led to more negative interpersonal ratings. Given this empirical and theoretical research, it stands to reason that expressing stigmas that are perceived as more controllable will be more likely to lead to worse outcomes. Thus, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 6

Perceived controllability will moderate the relationships between expression and (a) intrapersonal, (b) interpersonal, (c) workplace, and (d) non-workplace outcomes, such that these relationships will be positive, especially for stigmas that are perceived to be less controllable.

Contextual Moderators

Setting

The relationship between expression and positive outcomes likely depends on the setting that is used. Typically, researchers either conduct studies in a laboratory setting or a field setting. In a laboratory setting, undergraduate students often either receive an expression or suppression condition through vignettes or interactions with a confederate, and outcomes of such hypothetical scenarios are examined (e.g., Hebl & Kleck, 2002; Hebl & Skorinko, 2005; Wessel, Hagiwara, Ryan, & Kermond, 2015). In contrast, researchers conducting studies in field settings typically survey individuals or employees regarding the intrapersonal and interpersonal outcomes that they personally experienced as a result of their own expression decisions (e.g., Day & Schoenrade, 1997, 2000; Griffith & Hebl, 2002; Ragins & Cornwell, 2001) or they examine how individuals in the real world view others who express or suppress a stigmatized identity (e.g., Hebl et al., 2002; Morgan, Walker, Hebl, & King, 2013; Singletary & Hebl, 2009). The study design/setting is likely to influence these overall outcomes of expression (Frattaroli, 2006).

In field samples, researchers typically examine more permanent and long-lasting relationships. Individuals who have known each other for some time are likely to build stronger relationships before the stigmatized individual discloses this identity, which may be associated with more beneficial outcomes. Individuals who get to know and connect with a stigmatized target before an expression takes place likely view that target more favorably following the eventual expression. In lab and experimental studies, individuals receive expressions from ostensibly stigmatized targets immediately upon meeting them. Within these simulated interactions, individuals have less opportunity to form positive impressions of the targets that could have buffered against the negative interpersonal reactions associated with the devalued characteristic. Additionally, expressions that occur within these experiments may receive backlash because they occur too early during an interpersonal interaction, which may be viewed by others as socially inappropriate (Collins & Miller, 1994; Herek & Capitanio, 1996). Indeed, recent research on the timing of expression has suggested that expressing too early tends to elicit negative interpersonal reactions (King, Reilly, & Hebl, 2008). Thus, it is likely that expressions of stigmatized identities can produce more beneficial outcomes overall, but that these expressions will be received more negatively if they occur immediately upon interacting with a new individual, as often occurs in these hypothetical lab simulations. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 7

Setting will moderate the relationships between expression and (a) intrapersonal, (b) interpersonal, (c) workplace, and (d) non-workplace outcomes, such that these relationships will be positive, especially for field studies vs. lab studies.

Recipient Gender

Research on self-disclosure (broadly defined) has often examined differences in the gender of the recipient of the disclosure (Collins & Miller, 1994; Derlega et al., 1993; Dindia & Allen, 1992). First, disclosure research has found that women are more likely than men to be the recipients of disclosures as their typical communication styles facilitate the disclosure or expression of personal information (Dindia et al., 2002). Alternatively, men may be more embarrassed or uncomfortable discussing intimate topics (Clair et al., 2005). Second, research on prejudice and discrimination typically finds mean differences in how women vs. men perceive and treat stigmatized others. Indeed, women are often more accepting of stigmatized identities such as sexual orientation (Herek, Chopp, & Strohl, 2007) and thus, we presume that the gender of the recipient will influence the outcomes of expression such that expressions to women will be more associated beneficial outcomes. Thus, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 8

Gender of recipient will moderate the relationships between expression and (a) intrapersonal, (b) interpersonal, (c) workplace, and (d) non-workplace outcomes such that these relationships will be positive, especially when interaction partners are women vs. men.

Differences Among Stigmatized Identities

There are various stigmatized identities that have been studied in the literature, and we inductively explore the differences among the outcomes of expression of these different identities. That is, we examine the overall positivity of the outcomes of expression (collapsing across our four domains of interest) for the 13 primary stigmas identified in our literature search (sexual orientation, religion, gender, race, mental illness, physical disability, HIV status, pregnancy, gender identity, obesity, transgender identity, infertility status, and prior abortion). Differences in expression outcomes among these stigmatized identities could determine interesting patterns in the types of stigmas that are most and least beneficial to express.

Research Question 1

Do outcomes of expression differ based on the stigmatized identity?

Method

Literature Search

We utilized three methods for identifying articles in order to ensure that we had retrieved all relevant effect sizes for inclusion in this meta-analysis. First, journal articles and doctoral dissertations were located through a search of the Google Scholar, PsycINFO, and Web of Science computerized databases. Searches in these databases were performed using various combinations of the following keywords: expression, disclosure, stigma identity management, stigma expression, stigma suppression, stigma acknowledgment, stigma visibility, and stigma impression management. Second, we scanned the reference lists of particularly applicable reviews (e.g., Ragins, 2008; Clair et al., 2005) for other relevant studies. Third, relevant conference papers and presentations were sought from authors who presented at the annual Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology (1998–2013) and Academy of Management academic conferences (1996–2013). These search strategies resulted in 155 articles for possible inclusion.

Criteria for Inclusion

Several decision rules were used to determine whether studies were eligible for inclusion in this meta-analysis. First, studies had to include adults of working age (18 and over). Second, the study needed to empirically examine the relationship between expression of any stigmatized identity and interpersonal and/or intrapersonal outcomes. Importantly, expression could either be manipulated in a lab setting or measured in a field setting; both possibilities fit our inclusion criteria.

Coding of Studies

Four psychology graduate students familiar with the literature and meta-analysis were involved in the coding of studies. Each of the 155 studies were coded by two coders to ensure appropriate levels of agreement. For each sample, the following information was recorded: (a) any effect sizes/significance tests of interest, (b) whether the effect was measuring intrapersonal or interpersonal outcomes, (c) whether the effect was examining a workplace or a non-workplace outcome, (d) sample size, (e) reliability of the independent variable(s), (f) reliability of the dependent variable(s), (g) the type of stigma under investigation, (h) the visibility of the stigma, (i) the controllability of the stigma, (j) the setting (lab or field study), and (j) the gender composition of the interaction partners. For both visibility and controllability, coders were told to rate each stigma based on societal perceptions. Specifically, for controllability, coders were instructed, “Please rate the extent to which society views the stigma of ___ as controllable” from 1 (completely uncontrollable) to 7 (completely controllable). Similarly, for visibility, coders were instructed, “Please rate the extent to which society views the stigma of ___ as visible” from 1 (completely invisible) to 7 (completely visible). These questions were worded in this way to mitigate response bias and control for the lack of generalizability in our sample of coders.

Several precautions were taken to ensure that coding was consistent across coders. As a first step, the four coders independently coded a small subset of studies and subsequently met to assess agreement. Because agreement was at an acceptable level (85%), the four coders continued to code independently of one another (with individuals from the same pair coding the same articles). This coding process resulted in a remaining sample of 65 studies, with a total of 108 effect sizes utilized in the final meta-analytic analyses.

Meta-analytic Calculations

The meta-analytic procedures proposed by Hunter and Schmidt (1990) were used to correct correlations for unreliability and to account for the effects of sampling error on the variance of the correlations. The accuracy of the meta-analytic effect size estimate was estimated using 95% confidence intervals constructed around the uncorrected sample size-weighted mean effect size using the standard error of uncorrected effect sizes. This indicated the extent to which sampling error influenced the estimate of the population effect size (Whitener, 1990). Homogeneity of effect sizes (whether the studies in the meta-analysis should be viewed as components of one or more sub-populations) were determined using 95% credibility intervals, which were created around the corrected sample-size-weighted mean effect size using the standard deviation of corrected effect sizes. A large credibility interval would imply that the mean (corrected) effect size is an estimate of the average of several subpopulation parameters (Whitener, 1990) and that moderator analyses are required.

Importantly, expression (our primary independent variable) could be manipulated in lab settings or measured in field settings within our primary studies. Thus, we converted all t and d statistics obtained from these experimental studies into correlations using the method developed by Hedges and Olkin (1985). These correlations were used in meta-analytic analyses to test our study hypotheses.

In addition to the 95% credibility intervals, the Q statistic was calculated in order to test for the presence of moderators (Hunter & Schmidt, 2004). In addition, we reported the I2 index (Huedo-Medina, Sánchez-Meca, Marín-Martínez, & Botella, 2006) in order to quantify the degree of heterogeneity in our samples. In order to aid in the interpretation of the I2 index, Higgins and Thompson (2002) proposed a tentative classification of I2 values: I2 = 25–50%, I2 = 50–75%, and I2 > 75% would be interpreted as reflecting a low, medium, and high amount of heterogeneity, respectively.

To test the extent to which these stigma characteristics moderated the expression-outcome relationships across the four domains of interest, we employed the subgroup method advocated by Hunter and Schmidt (2004). For continuous moderators, we regressed the effect sizes from each study onto the set of moderators using weighted least squares regression. Within this analysis, sample size was the weighted variable such that studies using larger samples were weighted more heavily than studies with smaller samples.

Lastly, we assessed for the potential impact of publication bias by visually examining funnel plots for symmetry and by statistically testing for funnel plot asymmetry with Egger’s test of regression (Egger, Smith, Schneider, & Minder, 1997). In all cases, we found that the funnel plots were relatively symmetric, and that Egger’s regression test was non-significant (p ≥ .39), suggesting that publication bias is unlikely to account for our findings. To examine for the potential of influential outliers, we examined studentized deleted residuals, Cook’s distances, and COVRATIO values (Viechtbauer & Cheung, 2010). In all, only two studies were identified as potentially important outliers (King et al., 2008; Wessel et al., 2015), and thus were further scrutinized. The two studies were unique in context (UK individuals with mental illnesses and US women in masculine job contexts) and help to provide a more robust picture of the overall state of the literature. Further, their removal did not significantly change our overall conclusions. Thus, in line with recommendations cautioning against removal of outliers in meta-analysis (Schmidt & Hunter, 2014; Schmidt, 2008; Viechtbauer & Cheung, 2010), we retain these studies in our analyses.

Results

Below, we present the main effects associated with expressing a stigmatized identity within each of the four outcome domains (intrapersonal, interpersonal, workplace, and non-workplace outcomes). For each of the four expression-outcome relationships of interest, we report the number of samples on which the estimate is based (k), the total sample size aggregated across studies (N), the mean sample-size-weighted uncorrected correlation (ro), and the mean sample-size-weighted corrected correlation (rc) (see Tables 1, 2, 3, 4). Furthermore, significant Q statistics for the overall expression-outcome relationship in all four outcome domains point to the presence of between study moderators: for intrapersonal outcomes, Q(40) = 194.43, p < .005; for interpersonal outcomes, Q(48) = 345.47, p < .005; for workplace outcomes, Q(32) = 119.00, p < .005; and for non-workplace outcomes, Q(51) = 12,186.5, p < .005. Given that the Q statistic for all outcomes was statistically significant, we display the results associated with categorical moderators for each of the outcome domains (see Tables 1, 2, 3, 4).

Following the analysis of main effects, we then test the hypothesized moderation effects. These continuous (visibility, perceived controllability) and categorical (setting, gender) moderators are tested with regard to each of the four expression-outcome domains for the sake of completeness. When comparing effect sizes associated with different levels of a categorical moderator variable, t statistics were computed following the procedure outlined by Aguinis, Sturman, and Pierce (2007) for evaluating the significance of meta-analytic moderator variables.

Main Effects

As can be seen in Table 1, the overall sample size-weighted corrected correlation between expression and positive intrapersonal workplace outcomes was rc = .12 (k = 40), 95% CI [− .03, .22]. Thus, expression of a stigmatized identity was not significantly related to intrapersonal outcomes, failing to support Hypothesis 1.

The overall sample size-weighted corrected correlation between expression and positive interpersonal outcomes was rc = .15 (k = 48), 95% CI [− .01, .26], as shown in Table 2. Therefore, expressing a stigmatized identity was not related to improved interpersonal outcomes, failing to support Hypothesis 2.

For workplace outcomes, the overall sample size-weighted mean corrected correlation was rc = .09 (k = 32), 95% CI [− .04, .21], as shown in Table 3. This finding did not support Hypothesis 3, which predicted that expressing a stigmatized identity would be associated with more positive workplace outcomes.

The overall sample size-weighted mean corrected correlation between expression and positive non-workplace outcomes was rc = .10 (k = 51), 95% CI [− .07, .22], as shown in Table 4. Thus, expressing was not associated with beneficial outcomes within non-workplace domains. Therefore, Hypothesis 4 was not supported.

Continuous Moderator Analyses

Four separate meta-regression analyses were performed in order to evaluate several continuous variables as potential moderators of the expression-outcome relationship. The continuous moderators of interest included visibility of stigma (coded on a 1–7 scale with lower numbers indicating less visibility) and perceived controllability (coded on a 1–7 scale with lower numbers indicating less perceived controllability). A dataset was constructed wherein each primary study reflected a separate case. The two continuous variables were entered as predictors into a weighted least squares regression (with larger samples weighted more heavily), and the effect size was entered as the dependent variable. The meta-regression of visibility and perceived controllability onto effect size was performed on the four domains of interest (intrapersonal, interpersonal, workplace, and non-workplace outcomes). Below, we present standardized beta weights for significant predictors to ease interpretation.

Visibility

Visibility did not moderate the expression-outcome relationship for intrapersonal outcomes (β = − .19, p = .25). Thus, Hypothesis 5a was not supported. Interestingly, visibility did moderate the expression-outcome relationship for interpersonal outcomes (β = − .301, p = .03), workplace outcomes (β = − .441 p < .01), and non-workplace outcomes (β = − .448, p < .01). As predicted, higher levels of stigma visibility weakened the positive outcomes associated with expression. Thus, Hypotheses 5b–d were supported.

Controllability

Perceived controllability did not moderate the expression-outcome relationship for intrapersonal outcomes (β = − .19, p = .37), interpersonal outcomes (β = − .15, p = .30), workplace outcomes (β = .02 p = .92), or non-workplace outcomes (β = − .25, p = .10). Thus, Hypothesis 6 was not supported.

Categorical Moderator Analyses

Setting

Moderator analyses suggested that the setting of the study (lab vs. field) did not moderate the relationship between expression and intrapersonal outcomes (t(4) = 1.76, p = .15). The effect size was rc = .06 for studies that took place in a lab setting (k = 3), and rc = .11 for those that took place in the field (k = 37). For interpersonal outcomes, setting did significantly moderate the expression-outcome relationship (t(16) = 3.76, p < .001). The average corrected effect size for studies examining expression in a lab was − rc = .09 (k = 9) whereas the corrected effect size for studies examining expression in the field was .15 (k = 23). For workplace outcomes, setting once again moderated these relationships (t(14) = 3.56, p < .001) such that studies examining expression in a lab setting yielded an effect size of − .04 (k = 8) whereas those examining expression in a field setting yielded an effect size of .14 (k = 24). Lastly, non-workplace outcomes of expression were also moderated by setting (t(18) = 3.33, p < .01) such that field settings elicited more positive outcomes of expression (.14, k = 41), compared to lab settings (− .11, k = 10). Thus, Hypotheses 8b–d were supported, but Hypothesis 8a was not.Footnote 1

Recipient Gender

Within the intrapersonal outcome domain, recipient gender did not moderate the expression-outcome relationship (t(36) = 1.49, p = .16). Expressions to men yielded an effect size of rc = .07 (k = 19) whereas those directed towards women, yielded an effect size of rc = .15 (k = 19). Among interpersonal outcomes, receiver gender did not moderate the expression-outcome relationship (t(28) = 1.89, p = .07), in that expressions to men yielded an effect size of rc = .09 (k = 15) whereas expressions to women yielded an effect size of rc = .21 (k = 27). For workplace outcomes, recipient gender did not significantly moderate these relationships (t(20) = 0.42, p = .68). For studies in which the recipients of expression were mostly male, the average corrected effect size was rc = .08, whereas for those in which the recipients were mostly female, the average corrected effect size was rc = .11. Lastly, the non-workplace outcomes of expression were significantly moderated by recipient gender (t(40) = 3.13, p < .01), such that studies in which the recipient of expression was mostly men yielded lower effect sizes (rc = − .01, k = 21). Compared to those in which recipients were mostly female (rc = .18, k = 28). Thus, only Hypothesis 9d was supported.

Type of Stigma

Lastly, we examined overall outcomes of expression for each stigmatized identity. This analysis collapsed across intrapersonal, interpersonal, workplace, and nonworkplace outcomes to examine whether expressing each stigma produced overall positive or negative outcomes. Interestingly, this analysis yielded significantly positive outcomes for expressions of sexual orientation (rc = .16 (k = 34), 95% CI [.02, .22]), and religion (rc = .23 (k = 40), 95% CI [.07, .32]). Expressing one’s gender yielded consistently negative outcomes (rc = − .29 (k = 2), 95% CI [− .31, − .17]). Expressions of all other stigmas did not significantly predict positive or negative outcomes (p > .05). Specific effect sizes for each form of stigma expression across all outcomes are presented in Table 5.

Discussion

The purpose of this meta-analysis was to determine the workplace, non-workplace, intrapersonal, and interpersonal outcomes of expressing one’s stigmatized identity, as well as boundary conditions for these relationships. This study found that expression was not related to positive intrapersonal outcomes, such as increased life and job satisfaction and decreased anxiety, stress, and depression. Expression also did not cause others to view and treat the stigmatized individuals more favorably, such as through more warm and affirming behaviors (Barron, Hebl, & King, 2011), or through rating the disclosed stigmatized individuals as more likeable and competent (Tagalakis, Amsel, & Fichten, 1988). Although theoretical arguments have been made suggesting that expressing a stigma should lead to improved intrapersonal outcomes while sacrificing interpersonal outcomes, the current findings suggest that this is not the case. Indeed, perhaps the most important finding from this meta-analysis is that individuals typically did not experience a backlash for expressing their stigmatized identities to others in terms of interpersonal outcomes.

Similarly, expressing a stigma did not relate to workplace outcomes, such as improved job satisfaction, decreased turnover intentions, and increased hireability and job evaluation outcomes. This is not entirely surprising, given the recent research on workplace expression that has often determined that there are various workplace costs and benefits of expressing and being open about one’s stigmatized identity (Clair et al., 2005; Ragins & Cornwell, 2001). Lastly, expression was not associated with positive outcomes in non-workplace domains. Thus, expressing a stigma was not associated with outcomes such as improved life satisfaction, decreased anxiety, and increased liking.

In sum, this meta-analysis found no direct outcomes of expression across the four domains under investigation (intrapersonal, interpersonal, workplace, and non-workplace outcomes). Thus, it seems as though expressing one’s stigma is associated with both positive and negative outcomes. Interestingly, our data suggest that outcomes depend on the visibility, study setting, and recipient gender associated with expression.

The visibility of one’s stigma was found to moderate the relationship between expression and interpersonal, workplace, and non-workplace outcomes. In accordance with our hypotheses, expression was associated with positive outcomes for stigmas that were less visible, but was not associated with positive outcomes for stigmas that were more visible. This finding supports the notion that expressions of visible stigmas are less surprising, meaningful, and interesting to others. Also, it may be the case that these expressions of previously visible stigmas were viewed as a form of advocacy or heightened pride in one’s stigma that may elicit more negative reactions compared to expressions that are truly invisible in nature. As such, these negative reactions may have counteracted the positive outcomes associated with expression.

It is also interesting to note that visibility did not moderate the relationship between expression and intrapersonal outcomes, meaning that visibility did not impact internal outcomes of being able to express these identities outwardly and openly to others. Thus, expressing was not associated with intrapersonal benefits, regardless of stigma visibility. This finding was surprising given that previous theoretical and empirical work has demonstrated that there are generally positive intrapersonal outcomes of stigma expression, especially for stigmas that are previously unknown (Clair et al., 2005; Munir et al., 2005; Ragins & Cornwell, 2001; Velez et al., 2013). Previous research has identified mixed findings regarding the interpersonal outcomes of expression. The differences in the visibility of stigmas that have been examined may help to elucidate these contradictory findings.

The perceived controllability of a stigma did not significantly impact the relationships between stigma expression and any of the investigated outcome domains, counter to our hypotheses and prior literature. There are many potential reasons for these findings. First, this may be due to the fact that previous work primarily examined the varying degrees of perceived controllability of the same stigma and how these differential perceptions impact reactions to expression. The one study that compared perceived controllability across stigmas only compared two specific stigmas (physical disability and obesity; Hebl & Kleck, 2002). Thus, studies have not previously compared the effects of expression across all stigmas with varying levels of controllability. Second, these results may suggest that the perceived controllability of a stigma has less of an impact as the perceived visibility of a stigma. Indeed, the visibility of a stigma is an extremely salient characteristic that is most easily and readily observable, which may account for these differences in the strength of these moderators.

The setting in which the study took place did moderate the relationship between expression and outcomes for interpersonal, workplace, and non-workplace outcome domains. As expected, field studies compared to lab studies yielded more positive effect sizes associated with expression, likely due to the fact that expressions within these studies occur among individuals that have deep, previously formed interpersonal connections. Alternatively, within these studies, the reverse may also be true in that stigmatized people may be better at selecting to whom they disclose (choosing to disclose only to people who are expected to be supportive) and when to disclose (making sure that they do not disclose too early or too late in a relationship). Thus, these outcomes are likely to be more positive in comparison to those associated with expressing in a lab setting, in which individuals are interacting with others during brief interpersonal interactions, in which they have no prior knowledge of each other. Thus, within these brief immediate interpersonal interactions, expressing a stigmatized identity yields less positive outcomes in terms of interpersonal, workplace, and non-workplace outcomes. Thus, stigmatized individuals in the real world may need to ensure that they are expressing to the right individuals at the right time in order to elicit positive reactions. Once again, setting did not moderate the expression-outcome relationship for intrapersonal outcomes. Thus, individuals did not report beneficial intrapersonal outcomes of expressing, regardless of the study setting.

Recipient gender also moderated the relationship between stigma expression and non-workplace outcomes. This is congruent with previous literature that demonstrates that individuals are more likely to disclose to women compared to men, and that women are more egalitarian and more accepting of expressions overall (Collins & Miller, 1994; Clair et al., 2005). Interestingly, these gender differences were only obtained for studies that examine non-workplace outcomes, such as perceived family supportiveness and life satisfaction. This may be explained by the fact that women are viewed as higher in warmth (Fiske et al., 2002) and warmth (relative to competence) is most salient within non-workplace and family domains (Cuddy, Glick, & Beninger, 2011).

Lastly, we found that the disclosure of a target’s religion and sexual orientation led to significantly positive outcomes, whereas the disclosure of a target’s gender led to significantly negative outcomes. These results align with our moderator analyses that show that revealing a less visible stigma, such as religion or sexual orientation, would relate to positive outcomes whereas revealing a more visible stigma, such as gender, would relate to negative outcomes. These findings also corroborate existing research on the backlash that women face for expressing or bringing up their gender or feminist identities (Roy, Weibust, & Miller, 2007; Wessel et al., 2015). Future research should examine the specific characteristics of gender that explain these consistently negative reactions.

Theoretical Implications

This meta-analysis has a variety of important theoretical implications. First, it demonstrates that stigma expression does not impact overall internal, external, workplace, and non-workplace outcomes. Results demonstrate that interpersonal reactions to expressions of stigma are generally neutral. Thus, the “disclosure dilemma” (Griffith & Hebl, 2002) may reflect an internal dilemma that does not often entail any real, negative interpersonal consequences. We are not proposing that stigmatized individuals face zero barriers compared to nonstigmatized individuals. Indeed, discrimination against various stigmatized groups continues to persist (EEOC, 2011). However, according to this meta-analysis, stigmatized individuals may not experience negative outcomes directly associated with their decisions to express or suppress their identities, contradicting the assertions of stigma theory. Second, as we found in our moderator analyses, however, there are specific conditions in which expressing actually relates to positive outcomes.

As predicted, interpersonal, workplace, and non-workplace outcomes of expression were more positive for less-visible stigmas. This is likely due to the fact that expressing/acknowledging these types of stigmas was less surprising and therefore less impactful. This finding is at odds with many theoretical and empirical studies that suggest that expressing stigmas that are more visible is more likely to lead to more positive interpersonal outcomes compared to expressing stigmas that are less visible (Hebl & Kleck, 2002; Hebl & Skorinko, 2005). However, this finding corroborates the tenets of general self-disclosure (Collins & Miller, 1994) and relationship-forming theories (Miller & Read, 1987) in that revealing information about one’s self that was not previously known or discernable is associated with the most positive interpersonal outcomes. Thus, it appears as though individuals appreciate gaining new information about others and do not necessarily appreciate when others continue to call attention to stigmas that are immediately observable.

Interestingly, this study did not find that the perceived controllability of a stigma moderated the expression-outcome relationship for any of the four outcome domains. This finding was surprising given previous theoretical and empirical work, which suggested that expressing stigmas that are perceived as controllable would be more likely to lead to more negative interpersonal reactions (Hebl & Kleck, 2002; Jones et al., 1984). This finding may be explained by the fact that stigma visibility accounts for the greatest variance in these expression-outcome relationships, and thus should continue to be the focus of stigma identity management research. This builds on previous work by demonstrating that the various dimensions of stigma do not equally determine the valence of expression outcomes.

This study suggests that the interpersonal reactions to stigma expression are based not on the stereotypes or nature of the stigmatized identities in question, but rather on the degree of information that is being shared. Counter to stigma theory (Goffman, 1963) but in alignment with theories of general self-disclosures (Collins & Miller, 1994) and relationship forming (Miller & Read, 1987), expressing stigmatized identities that were previously unknown is associated with the most positive intrapersonal and interpersonal outcomes, regardless of the negative attributions that may accompany the specific identities in question.

Practical Implications

This study identifies the specific conditions that facilitate positive outcomes for stigmatized targets within workplace and non-workplace domains. The information in this meta-analysis can be used to help workplaces and policy makers to determine potential individuals that are most vulnerable or most likely to experience negative outcomes of expression. Indeed, this meta-analysis could be useful to practitioners interested in maximizing the inclusion, acceptance, and ultimately, the effectiveness of stigmatized individuals, especially within workplace domains.

In addition, this meta-analysis would be especially useful to stigmatized individuals and employees who are interested in optimizing their own internal and external outcomes. Indeed, the decision to disclose is often based on a cost-benefit analysis of the internal and external advantages and disadvantages of expressing (Clair et al., 2005). According to this meta-analysis, many of the fears that stigmatized individuals have about expressing their stigmas leading to negative reactions and repercussions from others may be unjustified, in that these individuals do not experience interpersonal harm by suppressing their identities.

In fact, for stigmas that are less visible, expressing is associated with more positive interpersonal, workplace, and non-workplace outcomes. Expressing stigmas that are more visible is not associated with these same positive outcomes, and thus, visibly stigmatized targets should utilize other identity management strategies, such as increased positivity (Singletary & Hebl, 2009) or providing individuating information (Singletary & Hebl, 2009; Morgan et al., 2013). Also, this meta-analysis determined that the visibility of a stigmatized identity is more important than the perceived controllability of a stigma in terms of its moderating influences on the positivity of these outcomes. This study also found that non-workplace outcomes of expression are more positive when interaction partners are women compared to men. Lastly, this study found that expression was associated with generally positive outcomes for sexual orientation and religious minorities and negative outcomes for women.

Limitations and Future Directions

This meta-analysis was limited in the amount of studies included for certain stigmatized identities such as religion and physical disability. Given the increasing number of EEOC cases filed for religious discrimination claims (EEOC, 2003) and the increase in islamophobia (Sheridan, 2006), as well as the salience of the ADA in HR practice (Durlak, 2017), it is critically important to better understand how expressing these particular stigmas influences workplace experiences. Relatedly, more could have been done to incorporate time into the current meta-analysis, and future research should identify how recent changes in societal prejudices and socio-political climates impact these expression outcomes.

This meta-analysis also did not have a large-enough sample size to examine intersectional effects. Given that stigmas do not occur in isolation and that these identities can often interact with other identities to produce multiplicative barriers (Berdahl & Moore, 2006), it is important to examine how individuals with multiple stigmatized identities engage in expression as well as the outcomes of these behaviors. Indeed, recent research has begun to show that expressing a more invisible stigmatized identity (such as an LGBTQ identity) may not produce similarly positive outcomes for those who also possess a more visible stigmatized identity (such as an African-American identity; Rosario, Schrimshaw, & Hunter, 2004). Clearly, more research incorporating an intersectional perspective is greatly needed.

Our meta-analysis was also limited given that most of the research identified was conducted within US contexts. More research examining expression outcomes in different contexts would be beneficial, especially given that cultural differences in individualism, egalitarianism, and uncertainty-avoidance likely influence expression outcomes. This work would be especially useful given the increasing globalization experienced by modern-day organizations (Morgan, 2007). Lastly, future research should examine the predictors of expression within and outside of the workplace. Doing so will help to paint a more complete picture of the individual and societal factors that predict stigma expression in addition to the outcomes of these stigma expression decisions.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis will hopefully help organizations, practitioners, and stigmatized individuals to maximally improve internal and external outcomes associated with having and managing their stigmatized identities in and out of the workplace. Theoretically, this study meta-analytically investigates the tenets of stigma theory and relationship-forming theories, and summarizes the interpersonal, intrapersonal, workplace, and non-workplace outcomes associated with expressing, disclosing, or acknowledging a stigmatized identity, as well as the boundary conditions that foster or inhibit these potentially positive outcomes. In general, expressing a stigma does not associated with consistently positive or negative outcomes, but characteristics of the stigma and of the context in which the expression takes place may relate to positive effects.

Notes

We also examined the study method (experiment vs. non-experiment) as a moderator but did not find any meaningful differences in our results given that there was a large overlap between study setting and study method.

References

References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the meta-analysis

Aguinis, H., Sturman, M. C., & Pierce, C. A. (2007). Comparison of three meta-analytic procedures for estimating moderating effects of categorical variables. Organizational Research Methods, 11, 9–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.1186.

*Ahmad, A. S., Lindsey, A. P., King, E. B., Sabat, I. E., Anderson, A. J., Trump, R., Keeler, K. R. (Unpublished). Interpersonal implications of religious identity management in the workplace. Journal of Applied Psychology.

Badgett, M. V., Lau, H., Sears, B., & Ho, D. (2007). Bias in the workplace: consistent evidence of sexual orientation and gender identity discrimination.

*Balsam, K. F., & Mohr, J. J. (2007). Adaptation to sexual orientation stigma: a comparison of bisexual and lesbian/gay adults. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54, 306–319. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.54.3.306.

*Barron, L. G., Hebl, M., & King, E. B. (2011). Effects of manifest ethnic identification on employment discrimination. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 17, 23–30. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021439.

*Beaber, T. (2008). Well-being among bisexual females: the roles of internalized biphobia, stigma consciousness, social support, and self-disclosure (unpublished doctoral dissertation). Alliant International University, San Francisco.

*Beals, K. P., Peplau, L. A., & Gable, S. L. (2009). Stigma management and well-being: The role of perceived social support, emotional processing, and suppression. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35, 867–879. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167209334783.

Berdahl, J. L., & Moore, C. (2006). Workplace harassment: double jeopardy for minority women. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 426–436.

*Berger, B. E., Ferrans, C. E., & Lashley, F. R. (2001). Measuring stigma in people with HIV: psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Research in Nursing & Health, 24, 518–529. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.10011.

*Bos, A. E. R., Kanner, D., Muris, P., Janssen, B., & Mayer, B. (2009). Mental illness stigma and disclosure: consequences of coming out of the closet. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 30, 509–513. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840802601382.

Brewer, M. B. (2007). The social psychology of intergroup relations: social categorization, ingroup bias, and outgroup prejudice. In A. W. Kruglanski & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Social psychology: handbook of basic principles (2nd ed., pp. 695–715). New York: Guilford.

Buck, D. M., & Plant, E. A. (2011). Interorientation interactions and impressions: does the timing of disclosure of sexual orientation matter? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47, 333–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2010.10.016.

Button, S. B. (2001). Organizational effectors to affirm sexual diversity: a cross-level examination. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.17.

Button, S. B. (2004). Identity management strategies utilized by lesbian and gay employees. Groups & Organization Management, 29, 470–494. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601103257417.

*Calin, T., Green, J., Hetherton, J., & Brook, G. (2007). Disclosure of HIV among black African men and women attending a London HIV clinic. AIDS Care, 19, 385–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540120600971224.

Charmaz, K. (1991). Good days, bad days: the self in chronic illness and time. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Clair, J. A., Beatty, J., & MacLean, T. (2005). Out of sight but not out of mind: managing invisible social identities in the workplace. Academy of Management Review, 30, 78–95. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2005.15281431.

Collins, N. L., & Miller, L. C. (1994). Self-disclosure and liking: a meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 116, 457–475. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.457.

Corrigan, P., & Matthews, A. (2003). Stigma and disclosure: Implications for coming out of the closet. Journal of Mental Health, 12(3), 235–248.

*Comer, L. K., Henker, B., Kemeny, M., & Wyatt, G. (2000). Illness disclosure and mental health among women with HIV/AIDS. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 10, 449–464. https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-1298(200011/12)10:6<449::AID-CASP577>3.0.CO;2-N.

Crocker, J., Major, B., & Steele, C. (1998). Social stigma. In D. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (Vol. 2, 4th ed., pp. 504–553). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Cuddy, A. J. C., Glick, P., & Beninger, A. (2011). The dynamics of warmth and competence judgments, and their outcomes in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 31, 73–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2011.10.004.

*Dalgin, R. S., & Bellini, J. (2008). Invisible disability disclosure in an employment interview: impact on employers’ hiring decisions and views of employability. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 52, 6–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/0034355207311311.

Day, N. E., & Schoenrade, P. (1997). Staying in the closet versus coming out: relationships between communication about sexual orientation and work attitudes. Personnel Psychology, 50, 147–163. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1997.tb00904.x.

Day, N. E., & Schoenrade, P. (2000). The relationship among reported disclosure of sexual orientation, anti-discrimination policies, top management support and work attitudes of gay and lesbian employees. Personnel Review, 29(3), 346–363.

Derlega, V. J., Metts, S., Petronio, S., & Margulis, S. T. (1993). Sage series on close relationships. Selfdisclosure. Thousand Oaks, CA, US.

*Dima, A. L., Stutterheim, S. E., Lyimo, R., & de Bruin, M. (2014). Advancing methodology in the study of HIV status disclosure: the importance of considering disclosure target and intent. Social Science & Medicine, 108, 166–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.02.045.

Dindia, K., & Allen, M. (1992). Sex differences in self-disclosure: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 106–124.

Dindia, K., Allen, M., Preiss, R., Gayle, B., & Burrell, N. (2002). Self-disclosure research: knowledge through meta-analysis. Interpersonal communication research: Advances through meta-analysis, 169–185.

*Driscoll, J. M., Kelley, F. A., & Fassinger, R. E. (1996). Lesbian identity and disclosure in the workplace: Relation to occupational stress and satisfaction. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 48, 229–242. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1996.0020.

Durlak, P. R. (2017). Disability at work: understanding the impact of the ADA on the workplace. Sociology Compass, 11, e12475.

EEOC (2003). Muslim/Arab employment discrimination. Charges since 9/11. Available at: http://www.eeoc.gov/origin/z-stats.html

EEOC (2011). Charge statistics FY 1997 through FY 2010. Available at: http://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/statistics/enforcement/charges.cfm

Egger, M., Smith, G. D., Schneider, M., & Minder, C. (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ, 315, 629–634. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629.

Ellis, A. L., & Riggle, E. D. B. (1996). The relation of job satisfaction and degree of openness about one’s sexual orientation for lesbian and gay men. Journal of Homosexuality, 30(2), 75–85. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v30n02_04.

*Emlet, C. A. (2006). A comparison of HIV stigma and disclosure patterns between older and younger adults living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 20, 350–358. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2006.20.350.

*Farina, A., & Ring, K. (1965). The influence of perceived mental illness on interpersonal relations. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 70, 47–51. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0021637.

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., Glick, P., & Xu, J. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 878–902. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.878.

Franke, R., & Leary, M. R. (1991). Disclosure of sexual orientation by lesbians and gay men: a comparison of private and public processes. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 10, 262–269. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1991.10.3.262.

Frattaroli, J. (2006). Experimental disclosure and its moderators: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 823–865. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.823.

Friskopp, A., & Silverstein, S. (1996). Straight jobs gay lives: gay and lesbian professionals, the Harvard Business School, and the American workplace. New York: Touchstone/Simon & Schuster.

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Upper Saddle River: Prentice-Hall.

Goodman, J. A. (2008). Extending the stigma acknowledgement hypothesis: a consideration of visibility, concealability, and timing of disclosure. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Maine, Orono.

*Griffith, K. H., & Hebl, M. R. (2002). The disclosure dilemma for gay men and lesbians: “Coming out” at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 1191–1199. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.6.1191.

*Hagiwara, N., Wessel, J. L., & Ryan, A. M. (2012). How do people react to stigma acknowledgment? Race and gender acknowledgment in the context of the 2008 presidential election. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 42, 2191–2212. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2012.00936.x.

*Hastorf, A. H., Wildfogel, J., & Cassman, T. (1979). Acknowledgement of handicap as a tactic in social interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 1790–1797. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.37.10.1790.

*Hebl, M. R., Foster, J. B., Mannix, L. M., & Dovidio, J. F. (2002). Formal and interpersonal discrimination: a field study of bias toward homosexual applicants. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 815–825. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167202289010.

*Hebl, M. R., & Kleck, R. E. (2002). Acknowledging one’s stigma in the interview setting: effective strategy or liability? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32, 223–249. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb00214.x.

*Hebl, M. R., & Skorinko, J. L. (2005). Acknowledging one’s physical disability in the interview: does “when” make a difference? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 35, 2477–2492. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2005.tb02111.x.

Hedges, L. V., & Olkin, I. (1985). Statistical methods for meta-analysis. Orlando: Academic Press.

*Herek, G. M., & Capitanio, J. P. (1996). “Some of my best friends” intergroup contact, concealable stigma, and heterosexuals’ attitudes toward gay men and lesbians. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22, 412–424. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167296224007.

Herek, G. M., Chopp, R., & Strohl, D. (2007). Sexual stigma: putting sexual minority health issues in context. In I. Meyer & M. Northridge (Eds.), The health of sexual minorities: public health perspectives on lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations (pp. 171–208). New York: Springer Science+Business Media, LLC.

*Hernandez, M. (2011). People with apparent and non-apparent physical disabilities: well-being, acceptance, disclosure, and stigma (unpublished doctoral dissertation). Alliant International University, San Francisco.

Hicks, G. R., & Lee, T.-T. (2006). Public attitudes toward gays and lesbians. Journal of Homosexuality, 51(2), 57–77. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v51n02_04.

Higgins, J. P. T., & Thompson, S. G. (2002). Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Statistics in Medicine, 21, 1539–1558. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.1186.

*Hudson, J. (2011). The disclosure process of an invisible stigmatized identity (unpublished doctoral dissertation). DePaul University, Chicago.

Huedo-Medina, T. B., Sánchez-Meca, J., Marín-Martínez, F., & Botella, J. (2006). Assessing hetereogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic of I2 index? Psychological Methods, 11, 193–206. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.11.2.193.

*Huffman, A. H., Watrous-Rodriguez, K. M., & King, E. B. (2008). Supporting a diverse workforce: what type of support is most meaningful for lesbian and gay employees? Human Resource Management, 47, 237–253. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20210.

Hunter, J. E., & Schmidt, F. L. (1990). Methods of meta-analysis: correcting error and bias in research findings. Newbury Park: Sage Publications, Inc..

Hunter, J. E., & Schmidt, F. L. (2004). Methods of meta-analysis: correcting error and bias in research findings (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc..

*James, M. X. (2010). Rainbow barrier behaviors: scale development and validation (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). The University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

Jones, E. E., Farina, A., Hastorf, A. H., Markus, H., Miller, D. T., & Scott, R. A. (1984). Social stigma: the psychology of marked relationships. New York: W.H. Freeman & Company.

Jones, E. E., & Gordon, E. M. (1972). Timing of self-disclosure and its effects on personal attraction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 24, 358–365. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0033724.

Jones, K. P., & King, E. B. (2013). Managing concealable stigmas at work: a review and multilevel model. Journal of Management, 40, 1466–1494. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313515518.

*Jordan, K. M., & Deluty, R. H. (1998). Coming out for lesbian women: its relation to anxiety, positive affectivity, self-esteem, and social support. Journal of Homosexuality, 35, 41–63. doi:https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v35n02_03.

*Juster, R.-P., Smith, N. G., Ouellet, É., Sindi, S., & Lupien, S. J. (2013). Sexual orientation and disclosure in relation to psychiatric symptoms, diurnal cortisol, and allostatic load. Psychosomatic Medicine, 75, 103–116. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182826881.

*Kalichman, S. C., DiMarco, M., Austin, J., Luke, W., & DiFonzo, K. (2003). Stress, social support, and HIV-status disclosure to family and friends among HIV-positive men and women. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 26, 315–332. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024252926930.

*Kimberly, J. A., & Serovich, J. M. (1996). Perceived social support among people living with HIV/AIDS. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 24, 41–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926189508251015.

King, E. B., Reilly, C., & Hebl, M. R. (2008). The best of times, the worst of times: exploring dual perspectives of “coming out” in the workplace. Group & Organization Management, 33, 556–601. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601108321834.

*King, M., Dinos, S., Shaw, J., Watson, R., Stevens, S., Passetti, F., … Serfaty, M. (2007). The stigma scale: development of a standardised measure of the stigma of mental illness. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 190, 248–254. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.106.024638.

*Lam, P. K., Naar-King, S., & Wright, K. (2007). Social support and disclosure as predictors of mental health in HIV-positive youth. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 21, 20–29. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2006.005.

Laurie, M. M. (2012). I tell or you tell: the intersection between stigmas and disclosure (Unpublished undergraduate honors thesis). Texas State University – San Marcos, San Marcos.

*Law, C. L., Martinez, L. R., Ruggs, E. N., Hebl, M. R., & Akers, E. (2011). Trans-parency in the workplace: how the experiences of transsexual employees can be improved. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79, 710–723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.03.018.

Legate, N., Ryan, R. M., & Weinstein, N. (2012). Is coming out always a “good thing”? Exploring the relations of autonomy support, outness, and wellness for lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3, 145–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550611411929.

*Lemke, A. (1995). Passing: a mediator of adjustment in learning disabled adults (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). New Mexico State University, Las Cruces.

*Letteney, S. G. (1997). HIV serostatus disclosure from mothers to children: Influencing factors. New York: Yeshiva University.

*Lindsey, A. P., King, E. B., Ahmad, A. S., Sabat, I. E., & Dong, Y. (Unpublished manuscript). Timing of disclosure of sexual orientation.

*Major, B., & Gramzow, R. H. (1999). Abortion as stigma: cognitive and emotional implications of concealment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 735–745. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.4.735.

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674.

Miller, L. C., & Read, S. J. (1987). Why am I telling you this? Self-disclosure in a goal-based model of personality. In V. J. Derlaga & J. H. Berg (Eds.), Self-disclosure: theory, research, and therapy (pp. 35–58). New York: Plenum Press.

*Mogengege, M.-A. (2008). If mama’s not happy, nobody’s happy: An exploration of the influence of stigma, disclosure and family coping on the transmission of maternal depression to children in African-American families affected by HIV/AIDS (unpublished doctoral dissertation). Washington: Howard University.

Mohr, J., & Fassinger, R. (2000). Measuring dimensions of lesbian and gay male experience. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 33, 66–90.

Moorhead, C. (1999). Queering identities: the roles of integrity and belonging in becoming ourselves. International Journal of Sexuality and Gender Studies, 4, 327–343. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023253513903.

Morgan, G. (2007). Globalization and organizations. In Introducing organizational behaviour and management (pp. 440–479). London: Thomson.

Morgan, W. B., Walker, S. S., Hebl, M. M. R., & King, E. B. (2013). A field experiment: reducing interpersonal discrimination toward pregnant job applicants. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98, 799–809. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034040.

*Munir, F., Leka, S., & Griffiths, A. (2005). Dealing with self-management of chronic illness at work: predictors for self-disclosure. Social Science & Medicine, 60, 1397–1407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.07.012.

Newheiser, A. K., & Barreto, M. (2014). Hidden costs of hiding stigma: ironic interpersonal consequences of concealing a stigmatized identity in social interactions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 52, 58–70.

Oswald, D. L. (2007). “Don’t ask, Don’t tell”: the influence of stigma concealing and perceived threat on perceivers’ reactions to a gay target. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 37, 928–947. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2007.00193.x.

Pachankis, J. E. (2007). The psychological implications of concealing a stigma: a cognitive-affective-behavioral model. Psychological Bulletin, 133, 328–345.