Abstract

Building on conservation of resources theory, we examined the duality inherent in one of the most significant work-related transitions an employee may go through: becoming a manager. Specifically, we explored intra-individual resource gains (i.e., increases in participation in decision-making) and resource losses (i.e., increases in time pressure) and their associations with intra-individual shifts in well-being (i.e., job satisfaction, exhaustion, and work-to-family conflict) when employees transitioned to a managerial position. In addition, we examined whether new managers’ perceived ability to detach from work during nonwork time moderated these processes. Multilevel analyses among 2052 individuals demonstrated that individuals experienced both a resource gain and a loss when they became managers. As expected, there was an indirect effect of the transition to a managerial position to an increase in job satisfaction via an increase in participation in decision-making. Additionally, there were indirect effects of the transition to a managerial position to an increase in both exhaustion and work-to-family conflict via an increase in time pressure. In line with the hypotheses, we found that new managers who perceived that they were able to detach well experienced a weaker increase in exhaustion and work-to-family conflict (as transmitted via an increase in time pressure). Contrary to the hypothesis, perceived ability to detach reduced the increase in job satisfaction (as transmitted via an increase in participation in decision-making). Our findings shed light on the intra-individual processes that occur when employees become managers, indicating that this transition can be a “double-edged sword.”

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Obtaining a managerial position constitutes a significant work-related role transition for employees (Ashforth, 2001; Hill, 1992; Louis, 1980). Because becoming a manager usually represents an upward career transition, it is often considered a key indicator of career success (e.g., Judge, Higgins, Thoresen, & Barrick, 1999). Many employees consider becoming a manager an attractive career goal (Bruce & Scott, 1994; Hill, 1992) and invest a significant amount of time and effort to obtain such promotions (e.g., Ng, Eby, Sorensen, & Feldman, 2005).

Initial qualitative research points to the notion that becoming a manager might, in fact, be a double-edged sword, thus alluding to the fact that this important career transition is a story of both gains and losses (Benjamin & O’Reilly, 2011; Hill, 1992, 2004): On the one hand, new managers often proudly mention their new influence and authority, while on the other hand they also lament about having to do too many things in too little time. Therefore, our overarching aim for the present study was to more comprehensively elucidate the intra-individual processes that unfold as employees become managers and examine how these processes are connected to work-related and nonwork-related well-being. Drawing on conservation of resources (COR) theory’s notion of gains and losses (Hobfoll, 1989, 2001), we predicted that the transition into a managerial role would be associated with intra-individual increases in two key job characteristics: participation in decision-making (as a form of resource gain) and time pressure (as a form of resource loss). Both job characteristics may capture the major changes that new managers encounter (see Benjamin & O’Reilly, 2011; Hill, 1992, 2004). These intra-individual gains and losses should, in turn, be differentially related to increases in key employee outcomes. In particular, we examined job satisfaction as the most typical attitude that encompasses individuals’ overall evaluation of their jobs (Judge & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2012), as well as exhaustion and work-to-family conflict as typical strain indicators that cover both the work and nonwork domain (Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu, & Westman, 2018).

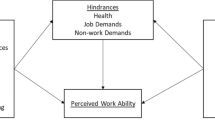

Furthermore, we examined the role of new managers’ ability to detach from work because it may help these individuals to benefit from resource gain and to more effectively deal with resource loss. As such, detachment refers to “refraining from job-related activities and mentally disengaging” from work during nonwork time (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2015, p. 72). It supports recovery from work demands and is important for employee well-being and performance capacity (see Sonnentag & Fritz, 2015, for a review). More pertinent to the current study, detachment can be influenced by individuals themselves (e.g., Hahn, Binnewies, Sonnentag, & Mojza, 2011). In the present context, being able to detach well thus appears highly relevant, because it may allow new managers to actively influence their transition process. Figure 1 displays the entire research model.

The present research extends the literature in several ways. First, we contribute to a more comprehensive picture of what it means to become a manager. In particular, we build upon one of COR theory’s less studied tenets, namely the notion that there can be “ambiguous” events in individuals’ lives that have the potential to trigger both resource gain and loss processes simultaneously (Hobfoll, 1989, p. 518). Adding to some first studies in the nonwork context (Hou, Law, Yin, & Fu, 2010; Wells, Hobfoll, & Lavin, 1999), we tested this notion in the context of managerial transitions as a major career event. In addition, we also add to the general trend of utilizing COR theory beyond solely predicting stress-related outcomes (Hobfoll et al., 2018). By considering both positive (i.e., job satisfaction) and strain-related outcomes (i.e., exhaustion and work-to-family conflict), we thus contribute to a more holistic application of COR theory’s predictions.

Second, we extend knowledge on resources that can help new managers more effectively master their transition. In a survey of new managers, Paese and Wellins (2007) discovered that two thirds of respondents reported obstacles and difficulties in their transition to becoming a manager, highlighting the need to conduct research in this field (see also Sokol & Louis, 1982). Thus far, research has identified some beneficial resources in the work domain (Dragoni, Park, Soltis, & Forte-Trammell, 2014; Hill, 1992). We extend this literature with a work recovery perspective. In particular, we identify new managers’ ability to detach as a resource that emanates from their nonwork lives and which can be actively shaped or trained by individuals (Hahn et al., 2011).

Third, by using a within-person approach, we respond to the call to study resource gain and loss processes from a dynamic perspective that adequately addresses the issue of time (Halbesleben, Neveu, Paustian-Underdahl, & Westman, 2014; Hobfoll et al., 2018). Using data from a large-scale panel study, we tested our hypotheses in a sample of 2052 individuals who transitioned from a nonmanagerial to a managerial position. By applying discontinuous change modeling, we were thus able to compare the time periods before and after the transition to a managerial position. Moreover, in that we followed the same individuals over time, we could also more systematically and explicitly examine what it means to become a manager. We thus extend previous knowledge gained from between-person studies that compared managerial with nonmanagerial jobs (e.g., Morgeson & Humphrey, 2006).

Transition to a managerial position and the story of gains and losses

Hobfoll’s COR theory (1989, 2001) highlights the value that resources have for individuals; resources can include both intangible (e.g., health and self-esteem) and tangible aspects (e.g., money or a house). We particularly build upon the theory’s notion of “ambiguous” events that can trigger both resource gains and losses simultaneously. The present context of becoming a manager is especially unique in this regard for several reasons. First, the transition to a managerial position denotes a form of inter-role transition, whereby a new and different role is taken, entailing numerous new tasks and responsibilities (Bruce & Scott, 1994; Louis, 1980). Nicholson and West (1988) noted that moving up the career ladder is one of the most demanding career transitions an individual can encounter. Second, while not all individuals strive for a managerial position, many employees aim for this kind of progression in their careers, looking forward to this transition with excitement and optimism (Hill, 1992). Thus, in contrast to other events that might likewise carry some ambiguity (Hobfoll, 1989), potential negative aspects of becoming a manager might be somewhat less salient to individuals. Based on her interview studies, Hill (2004) noted that new managers “had grossly underestimated” (p. 122) the challenges they would face along their way.

Thus far, qualitative work in the area of managerial transitions, as well as empirical studies comparing nonmanagerial to managerial jobs, have pointed to the aforementioned duality, indicating that managers encounter more authority, independence, and freedom (Jamal, 1985; Lundqvist, Reineholm, Gustavsson, & Ekberg, 2013; Nicholson & West, 1988). In a similar vein, Paese and Wellins (2007) found that new managers felt highly motivated by the “greater opportunity to make things happen” (p. 10), and Hill (2004) noted that “what attracted them [the new managers] to management was the prospect of having more authority and freedom” (p. 121). At the same time, new managers are confronted with an increased number of tasks and responsibilities (see Fayol’s, 1916, classical managerial activities of planning, commanding, coordinating, and controlling). These multiple activities usually span technical, human, and conceptual issues (Hill, 2004) and can severely challenge their time- and energy-related resources (Benjamin & O’Reilly, 2011; Hill, 1992). For example, in interviews that Hill (1992) conducted with new managers, individuals mentioned the “unrelenting workload and pace” (p. 54) of being a manager and described themselves as being “firefighters” (p. 55) in their new positions.

Based on the above descriptions, it becomes clear that two work characteristics are likely to encompass the major intra-individual gains and losses that new managers can be expected to experience, namely participation in decision-making and time pressure. To start with, participation in decision-making refers to the influence that individuals have in organizational decisions (e.g., Lam, Chen, & Schaubroeck, 2002). The construct constitutes a form of autonomy (e.g., Morgeson & Humphrey, 2006) that goes beyond the operational level of a person’s job and entails influence in the strategic part of an organization. Due to the higher hierarchical level that individuals obtain as they transition to a managerial role, participation in decision-making is likely to play a pivotal role in this context (see Nicholson & West, 1988). Moreover, in addition to its relevance in the managerial context, participation in decision-making and its related forms also occupy a central role in several other theories related to work design and work motivation (Bakker, Demerouti, & Sanz-Vergel, 2014; Hackman & Oldham, 1976; Karasek, 1979). In the context of COR theory, experiencing an intra-individual increase in participation in decision-making represents a constructive resource gain, because this resource type supports individuals’ goal accomplishment (Halbesleben et al., 2014).

In contrast, time pressure refers to having to work at a fast pace, potentially skipping breaks and working longer than usual due to one’s high workload (Major, Klein, & Ehrhart, 2002; Roe & Zijlstra, 2000). Based on the increased number of different tasks and responsibilities that new managers have (Benjamin & O’Reilly, 2011; Dierdorff, Rubin, & Morgeson, 2009) as well as the findings by Hill (1992), the construct of time pressure is thus particularly likely to integrate several striking features of new managers’ work. Time pressure constitutes a key characteristic in theories related to job design (Karasek, 1979) and stress (Bakker et al., 2014). Along the lines of COR theory, intra-individual increases in time pressure represent a resource loss (Hobfoll, 2001; see also Lee & Ashforth, 1996); that is, in order to fulfill their multiple role demands, new managers should experience an increased investment and loss of the valued resource of time (see also the classical work by Mintzberg, 1980, highlighting that the issue of time loss and expenditure plays a central role in managers’ working life).

Taken together, we propose that individuals who transition from the pre-manager to the manager phase may experience significant increases in both participation in decision-making (a resource gain) and time pressure (a resource loss). By pre-manager phase, we refer to the year(s) before the transition to a managerial position (i.e., when the individual holds a nonmanagerial position); by manager phase, we refer to the year(s) including and after the transition to a managerial position (i.e., when the individual holds a managerial position). We thus examined shifts in both of these job characteristics between these two different phases within individuals (see also Louis’, 1980, design recommendations for examining role transitions). In the present study, we focused on individuals who had officially obtained a managerial role (in contrast to individuals who might have, for example, moved between different levels of management or those who experienced a shift in their supervising responsibilities without formally becoming a manager). We decided to do so because we assumed the formal step from a nonmanagerial to a managerial position to be the most drastic form of this role transition (see Hill, 1992; Nicholson & West, 1988), thus making the chosen sample particularly sensitive towards the proposed processes (for a similar recommendation, see Ployhart & Vandenberg, 2010).

Hypothesis 1a: Employees will experience an intra-individual increase in participation in decision-making from the pre-manager to the manager phase.

Hypothesis 1b: Employees will experience an intra-individual increase in time pressure from the pre-manager to the manager phase.

Managerial transitions and the outcomes of gains and losses

Despite its classical focus on stress and strain processes (Hobfoll et al., 2018), COR theory in fact suggests that intra-individual resource gains and losses predict relatively different outcomes. In the context of this study, a resource gain is associated with increases in favorable job attitudes, because it builds up a sense of mastery and facilitates goal accomplishment and psychological growth; in contrast, a resource loss drains individuals’ resource reservoirs and is thus associated with indicators of employee strain (Hobfoll, 1989, 2001; Hobfoll et al., 2018). This view is reinforced by theories that propose the existence of two functionally independent systems for behavioral regulation in response to different types of events. Moreover, research suggests a valence-symmetry between the type of event and the subsequent affective state (e.g., Davidson, 1992; Gable, Reis, & Elliot, 2000; Gray, 1990; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). In support of this notion, Dimotakis, Scott, and Koopman (2011) have shown that positive workplace interactions were associated with positive affect, while negative workplace interactions were associated with negative affect.

The resource gain process and increases in job satisfaction

Within the context of this study, the above reasoning suggests that becoming a manager may, on the one hand, be associated with intra-individual increases in positive job attitudes. This attitudinal increase from the pre-manager to the manager phase may be transmitted via an intra-individual increase in participation in decision-making as an indicator of resource gain. In terms of job attitudes, we focus on job satisfaction as “a pleasurable or positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one’s job or job experiences” (Locke, 1976, p. 1300). Job satisfaction constitutes the most central job attitude and also has high relevance for subsequent behavior (Judge & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2012). Moreover, job satisfaction appears to be particularly relevant in the context of managerial transitions because individuals evaluate the very entity that is actually changing: their job (Judge, Weiss, Kammeyer-Mueller, & Hulin, 2017). Concerning the underlying mechanism, it has been argued that jobs become more enriched when characteristics related to autonomy increase (e.g., Morgeson & Humphrey, 2006). Thus, increases in participation in decision-making should be particularly motivating and satisfying for individuals. At the between-person level, meta-analytical results (Humphrey, Nahrgang, & Morgeson, 2007; see also Loher, Noe, Moeller, & Fitzgerald, 1985) demonstrate the predictive value of autonomy for job satisfaction.

Hypothesis 2a: Employees will experience an intra-individual increase in job satisfaction from the pre-manager to the manager phase.

Hypothesis 2b: The transition to a managerial position will be indirectly related (via an intra-individual increase in participation in decision-making) to an intra-individual increase in job satisfaction.

The resource loss process and increases in employee strain

Based on the above arguments, it follows that becoming a manager may also be associated with intra-individual increases in strain, and that this increase in strain from the pre-manager to the manager phase may be transmitted via an intra-individual increase in time pressure. The increased pace and limited time that characterizes time pressure (e.g., Roe & Zijlstra, 2000) is likely to deplete individuals’ resource reservoirs, which is reflected in increased levels of strain (Hobfoll, 1989). Put differently, the increased time pressure that new managers may encounter may force them to invest an excessive amount of energy in order to meet their performance standards—thus resulting in an increase in strain symptoms (see Cordes, Dougherty, & Blum, 1997).

The first strain indicator that we consider particularly relevant in the present context is exhaustion. The construct refers to a feeling of physical and emotional depletion and is often described as a key outcome of experienced resource loss and drained resource reservoirs (Halbesleben et al., 2014; Wright & Cropanzano, 1998). Exhaustion thus belongs to one of the most typical outcomes within the COR framework (Hobfoll et al., 2018). In the context of managerial transitions, exhaustion appears particularly impactful because it constitutes the most central dimension of burnout (e.g., Bakker et al., 2014; Maslach, Schaufeli, & Leiter, 2001). Although burnout can occur across all occupations, individuals in managerial positions are at particular risk for this symptom due to the highly interactive and fast-paced nature of their work (see Leiter, Bakker, & Maslach, 2014). Due to its role as a precursor of impaired functioning (Cropanzano, Rupp, & Byrne, 2003) and leadership (Lam, Walter, & Huang, 2017) at work, exhaustion gains further relevance in the managerial context. At the between-person level, meta-analytic results indicate strong relationships between exhaustion and several job stressors as indicators of resource loss, such as role stressors, workload, work pressure (i.e., stressors which are indicative of time-related pressure), and constraints at work (Lee & Ashforth, 1996).

Hypothesis 3a: Employees will experience an intra-individual increase in exhaustion from the pre-manager to the manager phase.

Hypothesis 3b: The transition to a managerial position will be indirectly related (via an intra-individual increase in time pressure) to an intra-individual increase in exhaustion.

The second strain indicator that we consider particularly relevant when transitioning to a managerial role is work-to-family conflict. This construct denotes a form of inter-role conflict in which the role pressures from the work and family domains are incompatible (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985). Although research has examined work-to-family conflict as well as family-to-work conflict (e.g., Michel, Kotrba, Mitchelson, Clark, & Baltes, 2011), our study will focus on the former, suggesting that the transition to a managerial position and the associated intra-individual increases in individuals’ time-related pressures may impact employees’ family domain. What is more, we view work-to-family conflict in line with the most agreed-upon sources of this conflict, namely that “the general demands of, time devoted to, and strain created by the job interfere with performing family-related responsibilities” (Netemeyer, Boles, & McMurrian, 1996, p. 401).

Considering work-to-family conflict is especially meaningful in the present context because we expand the focus of outcome variables by explicitly including a variable that goes beyond the work domain. Since individuals do, on average, spend more time working than in any other waking activity (Judge & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2012), it becomes crucial to examine the impact that managerial transitions can have on individuals’ well-being and functioning in the home domain. Indeed, Sokol and Louis (1982) already noted that role transitions affect “multiple arenas of a person’s life” (p. 83), and Benjamin and O’Reilly (2011) suggest that balancing work and family pressures is one of the biggest challenges for new managers (see also Paese & Wellins, 2007). By examining shifts in work-to-family conflict, we thus gain a more complete understanding of what it means to become a manager.

In the context of this study, COR theory suggests that increased demands in the work domain due to the transition should leave less resources available for the home domain (Hobfoll, 2001). Accordingly, in their work-home-resources model, ten Brummelhuis and Bakker (2012) suggest that work-to-family conflict occurs when demands in the work domain drain a person’s resources to such an extent that he or she is not able to function optimally at home (see also Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985). Results from a meta-analysis (Michel et al., 2011) based on between-person studies indicate that role overload (which is often used synonymously for time pressure at work) emerged as the strongest antecedent of work-to-family conflict (see also Byron, 2005).

Hypothesis 4a: Employees will experience an intra-individual increase in work-to-family conflict from the pre-manager to the manager phase.

Hypothesis 4b: The transition to a managerial position will be indirectly related (via an intra-individual increase in time pressure) to an intra-individual increase in work-to-family conflict.

Psychological detachment from work during nonwork time: a case of moderated indirect effects

COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989, 2001; Hobfoll et al., 2018) suggests that the above effects of intra-individual resource gain and resource loss can be affected by the availability of further resources. In particular, the theory states that employees who possess additional resources will be better able to benefit from resource gain, while at the same time these individuals are also better protected against incidents of resource loss. In the general context of role transitions, Sokol and Louis (1982) referred to the importance of resources, terming them “raw materials” (p. 85) through which individuals may better accomplish the task of transition. In the present context, new managers’ ability to detach from work during nonwork time may take the function of such a resource, which may help them benefit from intra-individual resource gain and deal with intra-individual resource loss more effectively. Psychological detachment refers to mentally disengaging from work during nonwork time (e.g., Etzion, Eden, & Lapidot, 1998; Sonnentag & Fritz, 2007) to recover from work demands. In the present study, we focused on new managers’ average level of their perceived ability to detach because it may indicate a pattern of experiences that allows them to recover from the demands of their new work role on a regular basis. Accordingly, Halbesleben et al. (2014) suggested that psychological detachment (during nonwork time) may constitute an important energy resource within the COR framework.

In terms of the resource gain process, we propose that new managers who are able to detach well from work during nonwork time may benefit more from the intra-individual increase in participation in decision-making which is in turn related to an intra-individual increase in job satisfaction. Thus, the positive intra-individual relationship between participation in decision-making and job satisfaction should be stronger under high levels of perceived ability to detach. We thus propose that a process of moderated (i.e., conditional) indirect effects occurs, such that the indirect effect of the managerial transition on the intra-individual increase in job satisfaction via the intra-individual increase in participation in decision-making may be stronger under high levels of new managers’ perceived ability to detach than under low levels of perceived ability to detach. In statistical terms, we propose that the posterior path in a classic mediation model, which links the mediator (i.e., participation in decision-making) with the outcome (i.e., job satisfaction), is moderated by an individual’s perceived ability to detach during the manager phase.

Hypothesis 5a: The indirect positive effect of transition to a managerial position on the intra-individual increase in job satisfaction (as transmitted via an increase in participation in decision-making) will be moderated by a person’s perceived ability to detach during the manager phase: Perceived ability to detach will strengthen the intra-individual positive relationship between participation in decision-making and job satisfaction, such that the positive indirect effect will be stronger under high levels of perceived ability to detach.

In terms of the resource loss process, and according to COR theory, a high ability to detach should further help new managers more effectively deal with the intra-individual increase in time pressure. According to the stressor-detachment model (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2015), detachment allows individuals to let go of their work-related thoughts and mental representations of job stressors (as indicators of resource loss), thus allowing them to recover from these demands. Indeed, some empirical research indicates the moderating role of detachment in the relationships between job demands (e.g., quantitative job demands) and employee strain (e.g., psychosomatic complaints, Sonnentag, Binnewies, & Mojza, 2010). In addition, one may also argue for this effect using the effort-recovery model (Meijman & Mulder, 1998). According to this model, individuals must invest effort in order to meet their demands at work (e.g., time pressure). As individuals invest effort, they experience load reactions—a process that is reversed through the process of recovery. Thus, as individuals detach from work, they allow their psychobiological systems to recover and to return to baseline levels.

Accordingly, we propose that in the case of new managers, perceived ability to detach may attenuate the positive intra-individual relationship between time pressure and exhaustion as well as work-to-family conflict. Hence, new managers who are able to detach well during nonwork time may be better able to deal with the intra-individual increase in time pressure resulting from the transition to this new role, thereby weakening intra-individual increases in exhaustion and work-to-family conflict. In other words, the resource loss caused by time pressure should be offset because detachment from work during nonwork time facilitates the recovery process. As such, the indirect effect linking the managerial transition to an intra-individual increase in exhaustion and work-to-family conflict via an intra-individual increase in time pressure should be weaker if new managers’ perceived ability to detach is high. Similar to hypothesis 5a above, new managers’ perceived ability to detach is assumed to moderate the posterior part of the indirect effect which links time pressure with the two strain outcomes.

Hypothesis 5b: The indirect positive effect of transition to a managerial position on the intra-individual increase in exhaustion (as transmitted via an intra-individual increase in time pressure) will be moderated by a person’s perceived ability to detach during the manager phase: Perceived ability to detach will weaken the intra-individual positive relationship between time pressure and exhaustion, such that the positive indirect effect will be weaker under high levels of perceived ability to detach.

Hypothesis 5c: The indirect positive effect of transition to a managerial position on the intra-individual increase in work-to-family conflict (as transmitted via an intra-individual increase in time pressure) will be moderated by a person’s perceived ability to detach during the manager phase: Perceived ability to detach will weaken the intra-individual positive relationship between time pressure and work-to-family conflict, such that the positive indirect effect will be weaker under high levels of perceived ability to detach.

Method

Sample

Data for this study came from the Swiss Household Panel (SHP, 2016), a yearly panel study that follows a random sample of households in Switzerland over time. The SHP was first implemented in 1999 and assessed 12,931 individuals. In 2004, the sample was extended with a refreshment sample of 6569 individuals. The core aim of the SHP is to observe social change through indicators such as income, job and marital status, and living conditions (SHP, 2016). The data were mostly collected through phone interviews. Generally, response rates of the SHP are relatively high, and attrition is low, such that longitudinal data are available for a large number of individuals (SHP, 2016). For testing our hypotheses, we used data from 2004 until 2012, because these waves continuously included all our variables of interest.

To identify participants who became managers during the aforementioned time periods, we searched for individuals who indicated having a managerial position (i.e., “Is supervising other employees’ work or telling them what to do an official part of your job?”) in 1 year (year t), but not the year before (year t − 1). This question was only asked if respondents were currently holding a job (i.e., they could not be unemployed). We then identified all consecutive years prior to the transition to manager (t − 1, t − 2, etc.); these years constituted the pre-manager phase (i.e., participants varied in the amount of pre-manager years); the transition year (year t) and all following consecutive years (t + 1, t + 2, etc.) in which participants reported having a managerial position constituted the manager phase (again, participants varied in the amount of years in this phase). In doing so, we created a “string” of consecutive years for every individual which indicated the years that belonged to the pre-manager phase and the manager phase, respectively. This approach was very conservative, because the identified strings contained no missing data. In other words, if a person indicated that he or she was a manager in year t and t + 1 but did not provide an answer to the manager question in year t + 2, the string stopped. The same applied to years in the pre-manager phase. If we identified more than one string per person (implying that a person changed from a nonmanagerial to a managerial position more than one time during the 9 years of data that were available), we only used information from the first string in our analyses.

For the analyses, we constructed a dummy variable, in which we coded all consecutive years of the pre-manager phase as “0” and all consecutive years of the manager phase as “1” (please see below for more detail). It was possible that individuals provided an answer to the manager item but failed to answer one or more of the other variables of interest. To make sure that all individuals included in the analysis had complete information during the transition phase, we excluded participants from our sample who had missing data in the last pre-manager year (year t − 1) or the first manager year (year t). If missing values were present in the years prior to or after the transition phase, we only removed the respective year from the dataset, but not the complete person. Thus, at least two observations per person were available for the analysis, which can be considered sufficient because the effects of interest were estimated across all individuals (Maas & Hox, 2005). Applying the aforementioned approach resulted in a final sample size of 2052 individuals (and 7467 measurement occasions) with a mean age of 39.6 years (SD = 13.3 years) and 44.4% males.

Measures

The data had a multilevel structure: yearly measurements (level 1) were nested within persons (level 2).

Level 1 variables

At the start of each survey, interviewers first reminded participants of when the previous survey took place. The surveys started by checking whether several demographic characteristics (e.g., marital status, nationality) had changed and whether any major life events (e.g., illness/accident of the person him-/herself or a closely related person, death of a closely related person, conflicts with a closely related person) had happened since the last survey. Thus, the time frame of reference that is made salient to participants is the elapsed time since the last survey (i.e., approximately a year). Time pressure was measured with the item “Do you have to work fast?” Response options ranged from 0 = never to 10 = all the time. Participation in decision-making was measured with the item “Within the responsibilities of your job, do you take part in decision-making, or provide advice on the management of the company?” Response options were 1 = yes, I take part in decision-making, 2 = yes, I provide advice to management, 3 = No. Participants’ answers on this item were re-coded, such that higher values represented a higher level of participation in decision-making. Job satisfaction was measured with the item “How satisfied are you with your job in general?” Response options ranged from 0 = not at all satisfied to 10 = very satisfied. Exhaustion was measured with the item “To what extent are you too exhausted after work to do the things you like to do?” Response options ranged from 0 = not at all to 10 = very strongly. Work-to-family conflict was measured with the item “How strongly does your work interfere with your private activities and family obligations, more than you would want this to be?” Response options ranged from 0 = not at all to 10 = very strongly.

Level 2 variable

Person-level perceived ability to detach during the manager phase was measured with the item “How difficult do you find it to disconnect from work when the work day is over?” Response options ranged from 0 = not difficult at all to 10 = extremely difficult. Answers were reverse coded prior to conducting the analyses, such that higher scores reflected higher levels of detachment. In order to have a person-level measure of this variable for the time period in which individuals were managers, we averaged all yearly measures of the manager phase.

Validation study

As our variables of interest were not operationalized with commonly used and validated measures, we conducted a validation study among 305 employees (for the same approach see Debus, Probst, König, & Kleinmann, 2012; Judge, Hurst, & Simon, 2009). We first administered all validated scales and then assessed the single items stemming from the SHP survey.Footnote 1 On average, individuals were 41.3 years old (SD = 11 years), 55.7% were males, and 66.6% worked full-time.

Participation in decision-making was measured with a 5-item measure by Lam et al. (2002); a sample item is “In this organization, my views have a real influence in company decisions.” To assess time pressure, we used a 5-item measure from the Instrument of Stress-Oriented Task Analysis (ISTA) by Semmer (1984); this measure is widely used in German-speaking countries and shows satisfactory to good validity (Semmer, Zapf, & Dunckel, 1999). A sample item is “How often does your work require a high pace?” Job satisfaction was measured with the three-item job satisfaction subscale of the Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire (Bowling & Hammond, 2008); a sample item is “All in all, I am satisfied with my job.” Exhaustion was measured with the eight-item exhaustion subscale of the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (Demerouti, Bakker, Vardakou, & Kantas, 2003). A sample item is “After my work, I regularly feel worn out and weary.” Work-to-family conflict was measured with a five-item scale developed by Netemeyer et al. (1996); a sample item is “The demands of my work interfere with my home and family life.” Detachment was measured with a four-item measure by Sonnentag and Fritz (2007). A sample item is “In the evenings, after work, I don’t think about work at all.”

The correlation between the participation in decision-making scale and the respective SHP item was r = .64 (corrected for the unreliability of the standard measure: rpartially disattenuated = .67), and the correlation for the time pressure measures was r = .79 (rpartially disattenuated = .85). The correlation for the job satisfaction measures was r = .87 (rpartially disattenuated = .92), and the correlations for the exhaustion and the work-to-family conflict measures were r = .78 (rpartially disattenuated = .83) and r = .84 (rpartially disattenuated = .87), respectively. Finally, the correlation between the detachment measures was r = .73 (rpartially disattenuated = .75). For all constructs, the correlation between the single items and the respective multi-item scale that measured the same construct (i.e., convergent validity) was higher than the correlations between the single items and the multi-item scales that measured any of the other constructs (i.e., discriminant validity). Thus, there is evidence that the SHP measures are at least commensurate with other established measures of these constructs.

Analytic technique

In general, hypotheses 1a, 1b, 2a, 3a, and 4a predict intra-individual shifts in variables (i.e., participation in decision-making, time pressure, job satisfaction, exhaustion, and work-to-family conflict) due to a distinct experience, namely becoming a manager. Thus, the hypotheses imply a model of discontinuous change (e.g., Hoffman, 2015; Singer & Willett, 2003), which we analyzed using multilevel modeling with the nlme package within the R program (Bliese, 2013, R Core Team, 2018; for a similar technique, see Halbesleben, Wheeler, & Paustian-Underdahl, 2013; Lucas, Clark, Georgellis, & Diener, 2004). The advantage of discontinuous change models is that they allow us to model shifts in certain variables of interest (Hoffman, 2015; Singer & Willett, 2003); that is, they do not assume a linear increase or decrease over time. All these models were two-level models in which the pre-manager and the manager years (and their respective values on the variables of interest) comprised level 1 data which were nested within persons at level 2. For assessing indirect effects (hypotheses 2b, 3b, and 4b) and moderated (i.e., conditional) indirect effects (hypotheses 5a, 5b, and 5c), we followed the procedures outlined by Preacher, Rucker, and Hayes (2007). See the results section below for more details.

To control for potential historical trends in average scores of our outcome variables, we centered the respective individual scores within each year (e.g., Lucas, Clark, Georgellis, & Diener, 2003). Thus, in order to exclude population-wide, general changes in the average levels of our outcome variables, we subtracted the mean of the entire SHP sample in a given year from each participant’s specific score in that same year.

Results

Table 1 displays the means, standard deviations, and zero-order correlations of the study variables. Before proceeding with the hypotheses tests, we estimated the amount of within- and between-person variability using the intra-class correlation coefficient for all outcome variables based on an intercept-only model (i.e., null model). Analyses revealed that in the case of participation in decision-making, 62% of the variance was explained by differences within persons (level 1), meaning that the remaining 38% was explained by differences between persons (level 2). The proportions of variance attributed to level 1 were 49% for time pressure, 56% for job satisfaction, 47% for exhaustion, and 52% for work-to-family conflict. Since the null model results showed substantial within-person variability for each of these variables, multilevel modeling of the data was deemed appropriate for all outcomes (e.g., Snijders & Bosker, 2012).

Hypotheses 1a and 1b: examining increases in participation in decision-making and time pressure

To test whether participation in decision-making and time pressure increased intra-individually from the pre-manager to the manager phase, we included a transition predictor (i.e., MANAGER) denoting the years that fell into the pre-manager and the manager phase; as indicated above, this variable was coded “0” for all years of the pre-manager phase and “1” for all years of the manager phase. For example, if a person was represented with three pre-manager and three manager years, this variable was coded 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1 for the 6 years. The respective model is illustrated in Eq. 1 (for the case of participation in decision-making as the outcome variable), in which participant is indicated as i and time is indicated as t. PDMit denotes the observed participation in decision-making of individual i at occasion t and β0 denotes the population intercept (i.e., the baseline level of participation in decision-making during the pre-manager phase). This period served as the reference time period (because all years of the pre-manager phase were coded as 0). Moreover, β1 denotes the population slope for the transition predictor (i.e., MANAGER) and thus represents the contrast in participation in decision-making between the pre-manager and the manager phase; b0i denotes the person-specific deviation from the intercept, and εit denotes the within-person error term.

Longitudinal multilevel models assume the level 1 residuals to be uncorrelated (Goldstein, Healy, & Rasbash, 1994; Rovine & Walls, 2006). Oftentimes in longitudinal analyses, this assumption is not met (instead, residuals are correlated over time). We therefore accounted for autocorrelation by modeling a first-order autoregressive process [AR(1)] for errors over time (Bliese, 2013, p. 73). This does not affect or change the interpretation of the effects estimated in the model. As can be seen in Table 2, the transition predictor MANAGER (β1) was significant for both participation in decision-making (t = 12.34, p < .001) and time pressure (t = 11.08, p < .001), thus suggesting a significant shift in the mean levels of both variables from the pre-manager to the manager phase. Because the predictor had a positive sign in both cases, this means that both participation in decision-making and time pressure increased intra-individually from the pre-manager to the manager phase. Thus, hypotheses 1a and 1b were supported.Footnote 2

Hypotheses 2a and 2b: examining increases in job satisfaction and the indirect effect via an increase in participation in decision-making

To test whether job satisfaction increased from the pre-manager to the manager phase, we ran the same model as depicted in Eq. 1 (with job satisfaction as the outcome variable). As can be seen in Table 3, the transition predictor MANAGER was nonsignificant (t = − 0.12, ns) implying that an intra-individual shift in job satisfaction from the pre-manager to the manager phase was not supported by the data. Thus, hypothesis 2a was not supported. Despite this nonsignificant result, we proceeded with our analyses of indirect effects; it might be the case that the predictor is related to the outcome only indirectly via the mediating variable (e.g., Kenny, Kashy, & Bolger, 1998).

To test hypothesis 2b, we applied the product-of-coefficients strategy outlined by Preacher et al. (2007, for further multilevel studies in which this method was used see Liu, Zhang, Wang, & Lee, 2011, for example) for computing the respective indirect effect ab. In these analyses, the a-path denotes the relationship between the predictor (i.e., MANAGER) and the mediating variable (i.e., participation in decision-making), which is the model that we ran for hypothesis 1a. The b-path denotes the association between the mediating variable (i.e., participation in decision-making) and the outcome (i.e., job satisfaction) when the predictor (i.e., MANAGER) is also included in the model.Footnote 3 Based on this information, we constructed 95% confidence intervals (CI) using the approach by Preacher et al. (2007, pp. 189–190) that assumes asymptotic normality of the indirect effect.

To adequately capture the intra-individual shift in the mediating variable in path b, participation in decision-making was centered around the individual’s mean during the pre-manager phase (e.g., Lucas et al., 2004). In doing so, we were able to remove all between-person differences in the level of participation in decision-making, thus arriving at a unique within-person estimate of shifts in the mediating variable. The estimated 95% CI indicated a significant indirect effect of the transition predictor on the intra-individual increase in job satisfaction via an intra-individual increase in participation in decision-making, because 0 was not included in the CI (95% CI [0.012, 0.029]; estimate = 0.020, SE = 0.005, z = 4.53, p < .001). Thus, hypothesis 2b was supported, implying that the transition to a managerial position was indirectly associated with an intra-individual increase in job satisfaction (via an intra-individual increase in participation in decision-making).

Hypotheses 3a and 3b: examining increases in exhaustion and the indirect effect via an increase in time pressure

To test hypotheses 3a and 3b, we applied the same procedure as described above. As can be seen in Table 3, the transition predictor was positive and significant in the case of exhaustion (t = 3.59, p < .001) indicating that individuals experienced an intra-individual increase in exhaustion from the pre-manager to the manager phase. Thus, hypothesis 3a was supported.

The estimated 95% CI indicated a significant indirect effect of the transition predictor on the increase in exhaustion via an increase in time pressure (95% CI [0.051, 0.085]; estimate = 0.068, SE = 0.009, z = 7.86, p < .001). Thus, hypothesis 3b was supported, implying that the transition to a managerial position was indirectly associated with an intra-individual increase in exhaustion (via an intra-individual increase in time pressure).

Hypotheses 4a and 4b: examining increases in work-to-family conflict and the indirect effect via an increase in time pressure

As can be seen in Table 3, the transition predictor was positive and significant in the case of work-to-family conflict (t = 4.32, p < .001). This indicates that individuals experienced an intra-individual increase in work-to-family conflict from the pre-manager to the manager phase. Thus, hypothesis 4a was supported.

The estimated 95% CI indicated a significant indirect effect of the transition predictor on the increase in work-to-family conflict via an increase in time pressure (95% CI [0.053, 0.089]; estimate = 0.071, SE = 0.009, z = 7.66, p < .001). Thus, hypothesis 4b was supported, implying that the transition to a managerial position was indirectly associated with an intra-individual increase in work-to-family conflict (via an intra-individual increase in time pressure).

Hypotheses 5a, 5b, and 5c: examining conditional indirect effects

To examine whether perceived ability to detach during the manager phase moderated the above indirect effects, we again followed the approach outlined by Preacher et al. (2007). We first estimated a model which built upon the model for the b-path described above, and additionally included the main effect of the moderator (i.e., detachmentFootnote 4) and the interaction between the mediating variable (i.e., participation in decision-making and time pressure, respectively) and the moderator (i.e., mediating variable × detachment interaction).Footnote 5 If the mediating variable × detachment interaction proved to be significant, we plotted the respective interaction at low (i.e., 1 SD below the mean) and high (i.e., 1 SD above the mean) values of the moderator and computed simple slopes. Afterwards, we computed conditional indirect effects at low and high values of the moderator and the corresponding CIs; for the exact formula see Preacher et al. (2007, pp. 199–203). To yield interpretability of the transition predictor MANAGER, detachment at level 2 and the predictor denoting the shift in the mediating variable were grand-mean centered (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003).

In the case of job satisfaction, the participation in decision-making × detachment interaction was significant (t = − 2.76, p < .01). Figure 2 displays the respective interaction plot. Simple slope tests showed that when perceived ability to detach was low, there was a significant positive intra-individual relationship between autonomy and job satisfaction (estimate = 0.146, SE = 0.023, z = 6.22, p < .001). When perceived ability to detach was high, there was no such relationship (estimate = 0.027, SE = 0.024, z = 1.15, ns). Calculating the aforementioned conditional indirect effects (see Table 4) revealed that the indirect positive effect of transition to a managerial position on the intra-individual increase in job satisfaction via an intra-individual increase in participation in decision-making was significant if a person’s level of perceived ability to detach during the manager phase was low; when perceived ability to detach was high, the indirect effect was nonsignificant. Because this finding was contrary to our assumption, hypothesis 5a was not supported.

In the case of exhaustion, the time pressure × detachment interaction was significant (t = − 1.99, p < .05). Figure 3 displays the respective interaction plot. Simple slope tests showed that there was a significant positive intra-individual relationship between time pressure and exhaustion at low levels of perceived ability to detach (estimate = 0.157, SE = 0.018, z = 8.80, p < .001). When perceived ability to detach was high, this relationship was weaker, albeit still significant (estimate = 0.110, SE = 0.016, z = 6.97, p < .001). Calculating the conditional indirect effects (see Table 4) revealed that the indirect positive effect of transition to a managerial position on the intra-individual increase in exhaustion via an intra-individual increase in time pressure was weaker under high levels as compared to low levels of perceived ability to detach during the manager phase. This finding was in line with our predictions. Thus, hypothesis 5b was supported.

In the case of work-to-family conflict, the time pressure × detachment interaction was significant (t = − 4.87, p < .001). Figure 4 displays the respective interaction plot. Simple slope tests showed that there was a significant positive intra-individual relationship between time pressure and work-to-family conflict at low levels of perceived ability to detach (estimate = 0.206, SE = 0.020, z = 10.51, p < .001). When perceived ability to detach was high, this relationship was weaker, albeit still significant (estimate = 0.080, SE = 0.017, z = 4.62, p < .001). Calculating the conditional indirect effects (see Table 4) revealed that the indirect positive effect of transition to a managerial position on the intra-individual increase in work-to-family conflict via an intra-individual increase in time pressure was weaker under high levels as compared to low levels of perceived ability to detach during the manager phase. This finding was in line with our predictions; thus, hypothesis 5c was supported.Footnote 6

Additional analyses

We also examined whether the transition to a managerial position would be indirectly related to an intra-individual decrease in job satisfaction via an intra-individual increase in time pressure. This was indeed the case (95% CI [− 0.016, − 0.001]; estimate = − 0.008, SE = 0.004, z = − 2.14, p < .05). Moreover, we examined whether the transition to a managerial position would be indirectly related to an intra-individual decrease in exhaustion and work-to-family conflict via an intra-individual increase in participation in decision-making. The respective indirect effects were nonsignificant in both cases (for exhaustion: 95% CI [− 0.019, 0.008]; estimate = − 0.006, SE = 0.007, z = − 0.803, ns; for work-to-family conflict: 95% CI [− 0.004, 0.026]; estimate = 0.011, SE = 0.008, z = 1.44, ns). Finally, perceived ability to detach did not moderate any of these additional indirect effects.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to more comprehensively investigate the intra-individual processes that occur when employees become managers, and to identify an important boundary condition of these process that can be actively affected by new managers themselves. Integrating COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989, 2001) and research on recovery from work (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2015) in the context of role transitions, our findings support the notion that becoming a manager is experienced as a double-edged sword, pointing simultaneously to both a resource gain and a resource loss. More specifically, our results indicate that becoming a manager was associated with an increase in participation in decision-making (as an indicator of resource gain) but also an increase in time pressure (as an indicator of resource loss). Furthermore, following the transition to manager, individuals experienced increases in exhaustion and work-to-family conflict. In line with our predictions, transition to a managerial position was indirectly related to an increase in job satisfaction via an increase in participation in decision-making (despite the fact that there was no total effect of the transition predictor on job satisfaction) and the increase in time pressure transmitted the effect of transition to a managerial position to an increase in exhaustion and work-to-family conflict. Our results further point to the importance of nonwork resources emanating from the home domain as a critical resource for new managers. More specifically, the indirect positive effects of the managerial transition on increases in exhaustion and work-to-family conflict via an increase in time pressure were weaker when managers perceived that they were able to detach well from work during nonwork time. This implies that new managers with high levels of perceived ability to detach were better able to deal with the intra-individual resource loss (in the form of time pressure) that they encountered.

Contrary to our hypothesis, perceived ability to detach during the manager phase reduced the indirect effect of the managerial transition on the increase in job satisfaction via an increase in participation in decision-making; more precisely, the indirect effect was no longer present when perceived ability to detach was high. This finding implies that if managers perceived that they were able to detach well from work during nonwork time, an increase in participation in decision-making was no longer experienced as a resource gain that lead to increased levels of job satisfaction. Although this finding may appear surprising at first sight, it corroborates recent empirical findings regarding the differential role of detachment in the context of affect spillover (i.e., the intra-individual transmission of affective states, e.g., Edwards & Rothbard, 2000) between the work and the home domain. In a daily diary study, Sonnentag and Binnewies (2013) found that, similar to our results, detachment inhibited spillover of negative affect between work and home because it enabled individuals to mentally disconnect from an unpleasant work situation. In the case of positive affect, a similar finding emerged: When employees experienced high levels of detachment, they could not benefit from positive work-related events, thus preventing a transfer of positive affect to the home domain. The authors argued that detachment acts as a useful vehicle for shrugging off negative events, but that it impedes benefitting from positive events because it mentally distances employees from the positive work situation. Relatedly, in the context of capitalization processes (i.e., turning to others to share good news), Gable and Reis (2010) argue that such processes can be explained by two mechanisms. First, if positive events can be shared with a responsive listener, this interaction boosts the perceived value of the event (termed maximizing, for empirical evidence, see Reis et al., 2010). Second, if individuals converse with others about a positive event, rehearsal, reliving, and elaboration occur, such that the event’s memorability is enhanced (for empirical support, see Gable, Reis, Impett, & Asher, 2004). Indeed, if new managers are generally able to detach well from work, both of these mechanisms are impeded such that capitalization effects are less likely to occur. Taken together, our findings thus point to the dual nature of detachment.

Several important conclusions can also be drawn from the results of our additional analyses. First, we found that the transition to a managerial position was also indirectly related to a decrease in job satisfaction via an increase in time pressure. This finding helps to further elucidate the fact that there was no total effect of the transition to a managerial position on intra-individual shifts in job satisfaction. In statistical terms, we thus found evidence for an inconsistent mediation (MacKinnon, Krull, & Lockwood, 2000). Hence, the transition to a managerial position was related to shifts in job satisfaction via opposing indirect effects which canceled each other out—thus resulting in the fact that, overall, new managers were not found to experience any shift in job satisfaction. In regard to the opposing indirect effects as well as the unexpected results for perceived ability to detach, we would like to note that these findings might also be due to the context specificity of our job satisfaction measure. Because job satisfaction was measured in relation to the person’s job at the time of assessment, respondents were rating their satisfaction with a subordinate job first and then, later on, with a managerial job. Thus, in contrast to the other measures employed in this study, the referent for job satisfaction changed over time, which may have influenced respondents’ scores differently than for the other measures.Footnote 7 Second, the finding that increases in participation in decision-making were not found to transmit the effect of the transition to a managerial position on shifts in the two strain outcomes provides further evidence for the notion of valence-symmetry referred to in the theory section (e.g., Dimotakis et al., 2011; Gable et al., 2000). Finally, the finding that indirect effects via increases in time pressure generalized to all outcomes further support one of the propositions of COR theory (e.g., Hobfoll, 2001), that resource loss is more salient than resource gain.

The results of our study extend the literature in a number of ways. First, and from a theoretical perspective, we contribute to the literature by building upon the notion of “ambiguous” events, an aspect of COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989) that has received surprisingly little research attention thus far (for exceptions in the nonwork context see Hou et al., 2010; Wells et al., 1999). More specifically, our findings indicate that specific events (here: becoming a manager) can simultaneously elicit gain and loss processes, that, consistent with the theory’s predictions, result in largely differential outcomes. Moreover, we draw attention to the impact that the availability of further individual resources (here: a person’s ability to detach) can have on the aforementioned gain and loss processes (Hobfoll et al., 2018). Consistent with COR theory’s propositions, we found evidence for the buffering role of a person’s perceived ability to detach in the resource loss process. Yet, contrary to the theory’s corollaries, a person’s ability to detach was not found to accelerate the resource gain process—in fact, it impeded it. As noted above, our findings thus point to the dual nature of detachment while also highlighting boundary conditions to some of COR theory’s predictions in the context of managerial transitions.

Second, by examining the managerial transition from a dynamic and within-person perspective, we applied an analytical approach that adequately matched the assumed theoretical process (see Mitchell & James, 2001). We thus conducted a more rigorous test of the intra-individual changes that employees experience when stepping into a managerial role, thus extending previous research that has been largely qualitative and descriptive. Moreover, this study adds important knowledge on the homology of certain relationships across levels. More precisely, we were able to determine that work characteristics that have been identified for managerial work (i.e., when comparing nonmanagers to managers) do in fact emerge intra-individually—that is, when individuals step into a managerial position. In doing so, this study adds to the notion of generalizability within multilevel theory (Kozlowski & Klein, 2000) and the within-subjects design has reduced the fallacy of inferring results which were found at a higher level of analysis (i.e., at the between-person level by comparing nonmanagers to managers) to lower levels (e.g., Gabriel et al., 2018; Hox & Kreft, 1994).

Finally, the use of publicly available panel data allowed us to model the aforementioned processes within a longer time frame. Although the use of such data is relatively common in sociology and economics (e.g., Bauer & Zimmermann, 1997; Scott, Alwin, & Braun, 1996), few studies within the field of organizational psychology have examined such large-scale, publicly available data (e.g., Judge et al., 2009; Kanazawa & Still, 2018; Kramer & Chung, 2015). Despite potential psychometric constraints around item and construct selection, these data provide a rich source of information for a variety of research questions that researchers may not normally be able to examine due to sampling issues.

Limitations and directions for future research

As with every study, ours is not without limitations. First, our study lacks the use of well-established multi-item scales. As noted earlier, the SHP is a yearly panel study administered to assess social change. Therefore, item selection is always a matter of compromise and constrains the choice of measures. Despite the fact that we conducted an additional validation study, we cannot fully determine the extent to which our single items comprehensively assessed the targeted constructs. Second, our results are based on a sample of working adults in Switzerland. Although the theoretical frameworks we used as a basis for our study (Hobfoll, 1989, 2001; Meijman & Mulder, 1998; Sonnentag & Fritz, 2015) suggest that the investigated processes should be independent of the cultural context, scholars should aim to replicate our findings in other countries and cultures.

Finally, we focused on participation in decision-making and time pressure as indicators of resource gain and resource loss, respectively. We chose these particular resources because we considered them to represent the major changes that occur when transitioning into a managerial role (e.g., Benjamin & O’Reilly, 2011; Hill, 1992, 2004; Nicholson & West, 1988). Yet, we are fully aware that these two characteristics might only be an excerpt of all possible changes that new managers might go through. Hence, there are certainly additional job characteristics (e.g., Hill, 1992; Mintzberg, 1980) that might be experienced as resource gains or losses, thus stimulating similar psychological mechanisms. For example, increases in perceived task significance (Hackman & Oldham, 1976) might be an additional resource gain. Task significance constitutes a motivational task characteristic (Morgeson & Humphrey, 2006) and reflects the degree to which the lives or work of others are affected (Hackman & Oldham, 1975). Task significance is proposed to be particularly high in jobs that involve dealing with other individuals (Hackman & Oldham, 1980)—thus making it likely that individuals will experience an increase in task significance from the pre-manager to the manager phase. Due to its motivating effect, task significance might likewise stimulate a resource gain process which triggers an increase in job satisfaction (see Humphrey et al., 2007). In terms of the opposing process, increases in role ambiguity might be an additional resource loss in the context of transitioning from a nonmanagerial to a managerial position. During their time as individual contributors, most individuals who later become managers were very clear about which performance-related behaviors were expected of them by their supervisors. Yet, as these individuals step into a managerial role, they might experience a loss of role clarity, for example by finding themselves in a position in which they need to coordinate their actions with many more individuals (e.g., seniors, peers, suppliers, customers) (Hill, 2004). Thus, it is conceivable that individuals who transition into a managerial position might experience an increase in role ambiguity, which may, in turn, cause increases in strain outcomes such as exhaustion and work-to-family conflict (see Örtqvist & Wincent, 2006).

Concerning future research on managerial transitions, we suggest that studies broaden the scope of outcome variables. In terms of outcomes of resource gains, it is conceivable that new managers might experience an intra-individual increase in organizational commitment. Because commitment refers to a person’s attachment to his or her organization, this construct might be a particularly relevant outcome of new managers’ experienced increase in participation in organizational decision-making (see Scott-Ladd, Travaglione, & Marshall, 2005). In terms of further outcomes of resource loss, it might be worthwhile to move beyond classical strain indicators, such as by examining surface acting (i.e., suppressing true emotions or faking non-felt emotions, Grandey, 2003) as a less beneficial behavior. Managerial work is very interactive (e.g., Hill, 2004) and requires high levels of empathy, thus rendering surface acting a highly relevant outcome. Previous research has shown that individuals engage in surface acting as a response to exhausted resource pools (Trougakos, Beal, Cheng, Hideg, & Zweig, 2015). Due to increased time pressure and related incidents of resource loss, individuals might likewise demonstrate an increase in surface acting as they transition to the managerial role. Moreover, it might also be fruitful to investigate constructs that qualify as outcomes of both processes. Job performance, for example, is affected by both the availability of resources such as participation in decision-making (Humphrey et al., 2007) as well as work conditions that signify the absence or loss of valued resources (Gilboa, Shirom, Fried, & Cooper, 2008).

As noted in the introduction, the majority of new managers experience challenges related to their transition (Paese & Wellins, 2007). Thus, future research may also benefit from examining additional resources that may help individuals master the transition process more effectively. As we mentioned previously, we particularly focused on new managers’ perceived ability to detach due to its malleability and because we aimed to connect the literature on work recovery to the literature on role transitions. Yet, resources which directly emanate from a person’s work situation, such as leader-member exchange (e.g., Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995) or supervisor social support (for empirical evidence see Dragoni et al., 2014), are likely to play an important role, too. Because new managers’ direct supervisors may serve as role models (Sims & Brinkman, 2002), receiving their loyalty and support may help new managers to better overcome potential hurdles along the way (Sokol & Louis, 1982). Moreover, individual differences could act as important boundary conditions in the postulated intra-individual gain and loss processes. In particular, self-efficacy, defined as “people’s judgements of their capabilities to organize and execute courses of action required to attain designated forms of performance” (Bandura, 1986, p. 391), might play such a role. On the one hand, self-efficacy might in fact help new managers to better utilize their new resource gain in the form of participation in decision-making, thus boosting its effect on increases in job satisfaction. On the other hand, self-efficacy has also been discussed in terms of how individuals appraise and cope with stressors in their environment (e.g., Jex & Bliese, 1999)—probably because individuals high in self-efficacy might more readily engage in problem-focused coping styles. Thus, individuals high in self-efficacy may more constructively deal with increases in resource losses, such as time pressure, thereby mitigating increases in strain.

Finally, in future research, scholars may also take a closer look at additional ways of capturing how individuals’ managerial responsibilities might change. In the present study, we operationalized the change to a managerial position as a discrete jump which entailed a formal shift in responsibilities. Thus, even if individuals may have already formally obtained a managerial position, they may still move between different levels of management—for example, when a coffee shop’s store manager becomes an area manager and is now executing organizational plans in accordance with the directives of top management. Despite the fact that this person already has experience in a management position, he or she may nevertheless experience significant resource gains and losses that can have an impact on his/her well-being. Moreover, it is also conceivable that individuals craft their jobs such that they obtain managerial responsibilities (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001). For example, a team member may voluntarily aid in the training and socialization of new employees, thereby gradually obtaining a supervising function without being formally appointed to do so. In sum, the above two examples illustrate that there are different ways in which managerial responsibilities may change. Thus, future research should delve deeper into the similarities and differences that such changes may entail.

Practical implications

Several practical implications can be drawn from the results of our study. First, due to the fact that there is a high demand for high-quality leadership (e.g., Spreitzer, 2006), it is vital for organizations to help new managers effectively master their transition and be able to successfully stay in their position for a long time. Hence, there is a huge market for leadership development programs aimed at new managers (e.g., American Management Association, 2017). In general, leadership training focuses on developing new managers’ leadership skills, including delegating, motivating employees, informed decision-making, communication skills, and team building approaches. Albeit effect sizes were relatively small in magnitude, our results highlight that leadership training should also make (new) managers aware of the potential negative consequences of their role for their well-being and work-to-family conflict. Such training should further teach (new) managers strategies to increase psychological detachment (e.g., setting work-nonwork boundaries, Bulger, Matthews, & Hoffman, 2007 and engaging in specific leisure experiences, e.g., Feuerhahn, Sonnentag, & Woll, 2014) during nonwork hours in order to effectively recover from work demands (e.g., Hahn et al., 2011). In a similar vein, our findings suggest that organizations may be advised to identify (new) managers who find it hard to detach well from work during nonwork time because these low levels may be a risk factor for poor manager well-being. These individuals may, in turn, be offered the above mentioned training opportunities, thereby sustaining effective leadership on a long-term basis.

Nowadays, many companies expect their employees to be constantly accessible via phone or email. Previous research has demonstrated that recovery from work is an essential process that helps employees sustain effective functioning at work (e.g., Binnewies, Sonnentag, & Mojza, 2009, 2010). As noted previously, detachment from work during nonwork time promotes effective recovery from work and fosters employee well-being (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2015), but it is important to note that detachment alone may not be able to replenish all spent resources. Other activities or experiences, such as physical exercise (e.g., Sonnentag, Venz, & Casper, 2017), can help individuals return to baseline levels of their functional systems and reduce strain. In sum, organizations could train upper management as well as subordinates to respect (new) managers’ work-nonwork boundaries (e.g., no calls or emails while on vacation). In other words, organizations can encourage managers (as well as all other employees) to engage in activities and to create experiences during nonwork time that allow for recovery from work.

Notes

In line with the three official languages in Switzerland, the SHP survey is administered in German, French, and Italian. Because German constitutes the largest language region in Switzerland (63%, Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, 2017), we conducted the validation study in the German-speaking part of Switzerland.

We also examined whether there was an intra-individual shift in participants’ perceived ability to detach from the pre-manager to the manager phase. Our analyses revealed that perceived ability to detach decreased from the pre-manager to the manager phase (t = − 4.56, p < .001).

For this model (in the case of job satisfaction as the outcome variable and participation in decision-making as the mediating variable), the regression equation was the following: Job satisfactionit = β0 + β1(MANAGERit) + β2(PDMit) + b0i + εit

For the sake of brevity, we will use the term “detachment” in the text when referring to the variable “perceived ability to detach” in our regression equations. In all tables and figures, we use the term “perceived ability to detach.”

For this model (in the case of job satisfaction as the outcome variable and participation in decision-making as the mediating variable), the regression equation was the following:

$$ \mathrm{Job}\ {\mathrm{satisfaction}}_{\mathrm{i}\mathrm{t}}={\beta}_0+{\beta}_1\left({\mathrm{MANAGER}}_{\mathrm{i}\mathrm{t}}\right)+{\beta}_2\left({\mathrm{PDM}}_{\mathrm{i}\mathrm{t}}\right)+{\beta}_3\left({\mathrm{Detachment}}_{\mathrm{i}}\right)+{\beta}_4\left({\mathrm{PDM}}_{\mathrm{i}\mathrm{t}}\right)\times \left({\mathrm{Detachment}}_{\mathrm{i}}\right)+{b}_{0\mathrm{i}}+{\varepsilon}_{\mathrm{i}\mathrm{t}} $$Because the participation in decision-making measure might not satisfy the assumptions of interval scale data, we re-ran analyses for hypotheses 1a, 2b, and 5a by dichotomizing the participation in decision-making item (i.e., we combined both yes-answers into one yes-category) according to the approach by Li, Schneider, and Bennett (2007). Results were nearly identical to our initial findings. Detailed results can be obtained from the authors.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing this out.

References

American Management Association. (2017). Management skills for new managers. Retrieved from http://www.amanet.org/training/seminars/Management-Skills-for-New-Managers.aspx. Accessed 7 Nov 2018.

Ashforth, B. E. (2001). Role transitions in organizational life: An identity-based perspective. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Sanz-Vergel, A. I. (2014). Burnout and work engagement: The JD-R approach. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1, 389–411. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091235.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood-Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bauer, T., & Zimmermann, K. F. (1997). Unemployment and wages of ethnic Germans. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 37, 361–377. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1062-9769(97)90073-9.

Benjamin, B., & O’Reilly, C. (2011). Becoming a leader: Early career challenges faced by MBA graduates. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 10, 452–472. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2011.0002.

Binnewies, C., Sonnentag, S., & Mojza, E. J. (2009). Daily performance at work: Feeling recovered in the morning as a predictor of day-level job performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30, 67–93. https://doi.org/10.1002/Job.541.

Binnewies, C., Sonnentag, S., & Mojza, E. J. (2010). Recovery during the weekend and fluctuations in weekly job performance: A week-level study examining intra-individual relations. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83, 419–441. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317909X418049.

Bliese, P. D. (2013). Multilevel modeling in R (2.5): A brief introduction to R, the multilevel package and the nlme package. Retrieved from https://cran.r-project.org/doc/contrib/Bliese_Multilevel.pdf. Accessed 7 Nov 2018.

Bowling, N. A., & Hammond, G. D. (2008). A meta-analytic examination of the construct validity of the Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire Job Satisfaction Subscale. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 73, 63–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2008.01.004.

Bruce, R. A., & Scott, S. G. (1994). Varieties and commonalities of career transitions: Louis’ typology revisited. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 45, 17–40. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1994.1024.

Bulger, C. A., Matthews, R. A., & Hoffman, M. E. (2007). Work and personal life boundary management: Boundary strength, work/personal life balance, and the segmentation-integration continuum. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12, 365–375. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.12.4.365.

Byron, K. (2005). A meta-analytic review of work-family conflict and its antecedents. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 67, 169–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2004.08.009.