Abstract

Little research has examined associations of social support with diabetes (or other physical health outcomes) in Hispanics, who are at elevated risk. We examined associations between social support and diabetes prevalence in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos Sociocultural Ancillary Study. Participants were 5,181 adults, 18–74 years old, representing diverse Hispanic backgrounds, who underwent baseline exam with fasting blood draw, oral glucose tolerance test, medication review, sociodemographic assessment, and sociocultural exam with functional and structural social support measures. In adjusted analyses, one standard deviation higher structural and functional social support related to 16 and 15 % lower odds, respectively, of having diabetes. Structural and functional support were related to both previously diagnosed diabetes (OR = .84 and .88, respectively) and newly recognized diabetes prevalence (OR = .84 and .83, respectively). Higher functional and structural social support are associated with lower diabetes prevalence in Hispanics/Latinos.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the U.S., ethnic minorities including HispanicsFootnote 1 are at higher risk for diabetes than non-Hispanic whites. The landmark Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Hispanics (HCHS/SOL), a prospective, population based cohort study of 16,415 Hispanic adults representing multiple ancestry backgrounds, recruited from four major U.S. metropolitan areas (2008–2011) reported an overall diabetes prevalence of 16.9 % (Daviglus et al., 2012; Schneiderman et al., In Press). Prevalence varied among the ancestry groups from 10.2 % in South Americans to a high of 18.3 % in Mexicans (Schneiderman, et al., In Press). Comparatively, in the 2005–2006 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, which, like the HCHS/SOL, included an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), prevalence of diabetes was 11.0 % among non-Hispanic white participants and 20.1 % among Hispanics of Mexican descent (Cowie et al., 2009). Other studies have shown that Hispanics with diabetes have poorer clinical control (Campbell et al., 2012), more complications, and higher mortality rates than their non-Hispanic counterparts (Harris 2001; Lanting et al., 2005). Additional research is needed to understand the risk and protective factors related to diabetes in Hispanics, given their disproportionate vulnerability and poorer outcomes.

More than three decades of research demonstrates that social ties and support are important to optimal health and longevity (Barth et al., 2010; Fortmann & Gallo, 2013; Pinquart & Duberstein, 2010; Uchino, 2006; Umberson et al., 2010). Social support definitions vary widely, but a central conceptual distinction can be made between structural features of social networks, such as the number and diversity of social roles or frequency of social contact that one experiences (i.e., structural support), and the function these networks serve in providing support to an individual (i.e., functional support) (Cohen et al., 1985; Lakey & Cohen, 2000). Functional support is often conceptualized as the perception that support resources, such as material aid, emotional support, companionship or information, would be available from one’s social network if needed (i.e., “perceived functional social support”) (Lakey & Cohen, 2000). Other studies have examined retrospective self-reports of received functional social support (Brissette et al., 2000). However, these support transactions tend to be situational and often arise in the context of stress. Consistently, received support has been less reliably associated with health benefits than has perceived support (Uchino, 2009). Thus, the vast majority of the literature has focused on indicators of structural support and perceived functional social support in efforts to understand influences on health and well-being (Uchino, 2009; Uchino et al., 2012).

Several reviews have concluded that low social support, defined variously, relates to higher risk of premature mortality from all causes (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010) and of cardiovascular disease (CVD) morbidity and mortality (Barth, et al., 2010; Mookadam & Arthur, 2004). A recent meta-analysis identified a more consistent association of perceived functional social support than of structural social support with CVD incidence and—especially—prognosis (Barth, et al., 2010). In contrast, only limited research has examined associations of social support with diabetes risk. A prospective study identified no relationship of functional or structural support with diabetes incidence over 10.5 years (Kumari et al., 2004). A case-referent study identified an association of low functional support with higher 8-year diabetes incidence in women, but not men, and observed no effect of structural support in either sex group (Norberg et al., 2007). Other studies have examined the association of social support at work with diabetes prevalence or incidence, however, a review and meta-analysis concluded that there is little evidence that low work social support relates to diabetes risk (Cosgrove et al., 2012).

Despite the limited direct evidence, a role of social support in the development of diabetes is biologically plausible through influences on neuroendocrine pathways associated with the development of visceral adiposity and insulin resistance (Buren & Eriksson, 2005; Uchino, 2006). Specifically, psychological stress activates the hypothalamic-pituitary–adrenal axis (HPA) and the sympathetic-adrenal-medullary (SAM) system, triggering increases in circulating glucocorticoids, such as cortisol and corticosterone, and catecholamines, including epinephrine and norepinephrine, respectively (Smith & Vale, 2006). When chronically activated these responses can contribute to metabolic dysregulation, ultimately increasing risks for diabetes and other chronic diseases (McEwen, 2012). Cortisol promotes increased glucose production from liver cells, and inhibits insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells, thereby encouraging insulin resistance over time (Beaudry & Riddell, 2012). Cortisol also stimulates lipolysis, increasing plasma free fatty acid levels, which in turn inhibits insulin release and further promotes glucose intolerance and insulin resistance (Peckett et al., 2011). There is also evidence of increased cortisol activity in abdominal visceral fat tissue, suggesting a mechanism through which cortisol may contribute to visceral fat accumulation (Kershaw & Flier, 2004). SAM-induced elevations in circulating catecholamines promote the production of inflammatory cytokines and acute phase proteins, such as C-reactive protein, creating an inflammatory state that is closely linked with dyslipidemia and insulin resistance (Black, 2006; Kyrou & Tsigos, 2009). Central obesity further amplifies the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and thus, obesity, insulin resistance, and inflammation represent interrelated pathways in the pathophysiology of diabetes (Olefsky & Glass, 2010; Tsatsoulis et al., 2013).

As an important psychosocial resource that can protect against the physiological impact of stress by attenuating perceptions of threat and promoting more adaptive coping (Thoits, 2011), social support could reduce risk for diabetes and other chronic conditions. In addition, provision or perceptions of social support have been shown to have direct effects on SAM and HPA functioning that are in opposition to those potentiated by stress (Uchino, 2006). Higher social support may also protect against the development of diabetes indirectly, through an association with preventive health behaviors such as increased physical activity and healthier dietary patterns (Thoits, 2011; Umberson, et al., 2010). In the context of diabetes specifically, greater support has been associated with improved diabetes self-management behaviors (Gallant, 2003) and, concordantly, better glycemic control (Stopford et al., 2013). In part this mechanism could also involve a multi-step pathway from social support, to physiological alterations, to behavior. For example, high levels of cortisol have been shown to foster resistance to the effects of leptin, increasing appetite and stress-related eating, and thus enhancing risk for obesity and metabolic dysregulation (Adam & Epel, 2007). Emotional pathways have also been suggested as an indirect pathway from social support to physical health (Thoits, 2011; Umberson, et al., 2010), although a recent review found little empirical evidence for the hypothesis (Uchino, et al., 2012).

To date, few studies have examined relationships of social support with diabetes or any other objective health outcome in Hispanics, a diverse, large, and rapidly growing U.S ethnic group (Pew Hispanic Center, 2011). The limited research has generally focused on individuals of Mexican descent and low socioeconomic status (Bell et al., 2010; Fortmann et al., 2011), compromising generalizability to the larger U.S. Hispanic population that represents a range of backgrounds. This scarcity of research is notable, given the salience of social relationships in traditional Hispanic cultural contexts (Caplan, 2007). Hispanics tend to be more collectivistic, family oriented and focused on maintaining smooth and positive social interactions relative to non-Hispanic Whites (Gallo et al., 2009; Perez & Cruess, 2011), although within group variability in experiential and behavioral factors certainly exists (Elder et al., 2009). In fact, researchers have theorized that certain health advantages experienced by Hispanics relative to non-Hispanic whites may be explained in part by cultural norms that prioritize warm, positive social interactions and strong family support systems (Jasso et al., 2004). Specifically, these protective social processes may represent one factor underlying epidemiological patterns suggesting that despite substantial social disadvantage (low socioeconomic status, poor healthcare access) (Pew Hispanic Center, 2014), and high rates of obesity and type 2 diabetes (Daviglus, et al., 2012; Kurian & Cardarelli, 2007), Hispanics appear to have lower CVD morbidity and mortality (Daviglus, et al., 2012; Go et al., 2013) and increased longevity relative to non-Hispanic whites (Arias et al. 2010). Often termed the “Hispanic Paradox”, these trends are supported by recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Cortes-Bergoderi et al., 2013; Ruiz et al., 2013), though contradictory findings have also been described (Teruya & Bazargan-Hejazi, 2013). In general, Hispanic health advantages are greater in foreign born than in U.S. born Hispanics, and they diminish with increasing time spent in the U.S. (Markides & Eschbach, 2011; Singh et al., 2013). In addition, some researchers have forecasted that health advantages of U.S. Hispanics will lessen in the coming decades as the population ages (Daviglus, et al., 2012) and as the full impact of childhood obesity (and disparities therein) are realized (Buttenheim et al., 2013). The HCHS/SOL (LaVange et al., 2010; Sorlie et al., 2010), and ancillary studies focused on sociocultural factors (Gallo et al., 2014) and health among the children of HCHS/SOL participants (Ayala et al., 2014; Isasi et al., 2014), will provide important insight into these epidemiological patterns and their changes over time in U.S. Hispanics.

Capitalizing on the unique HCHS/SOL cohort, the current study builds upon the limited research concerning the relationship of social support to diabetes and psychosocial correlates of Hispanic health, by examining associations of both functional and structural social support with diabetes prevalence in Hispanic adults of diverse ancestries. We hypothesized that higher levels of both structural and functional support would relate to lower diabetes prevalence. Given the cultural emphasis on maintaining strong positive relationships and social reciprocity in Hispanics, a high level of structural support could conversely impose a psychosocial or tangible burden that partially mitigates salubrious effects. For example, individuals with large networks may have many social responsibilities or obligations that tax their psychosocial resources (Pescosolido & Levy, 2002), or some relationships may be associated with both positive and negative features that on balance create stress (Uchino, 2013). Thus, we hypothesized that functional support would exhibit a stronger relationship with diabetes prevalence than would structural support when both types of support were examined conjointly. To help indirectly shed light on the temporal association between support and diabetes, additional analyses were conducted to separately examine associations of social support with diabetes cases diagnosed prior to the HCHS/SOL baseline exam versus cases that were newly recognized at baseline (i.e., so that participants were not aware of or actively managing their condition).

Methods

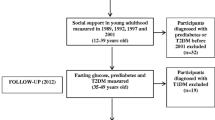

Participants and procedures

The HCHS/SOL is a prospective epidemiologic cohort study of chronic disease prevalence, incidence, and risk and protective factors in Hispanic individuals of Mexican, Cuban, Puerto Rican, Dominican, Central and South American, and other Hispanic ancestry, recruited from four field centers (the Bronx, NY, Chicago, IL, Miami, FL, and San Diego, CA). Details concerning the study sample (LaVange, et al., 2010) and approach (Sorlie, et al., 2010) have been reported previously. Participants who self-identified as Hispanic and were 18–74 years old at screening were recruited using a two-stage area household probability sampling approach, with oversampling of the 45–74 year age group. Participants attended a baseline exam with anthropometric assessment, fasting blood draw, 2-h OGTT, self-report sociodemographic and health assessments, and medication review. The current study used demographic data, body mass index (BMI), and diabetes diagnostic information obtained during the HCHS/SOL baseline exam.

Methods for the Sociocultural Ancillary Study have been presented elsewhere (Gallo, et al., 2014). The study was initiated to more thoroughly examine sociocultural correlates of health among HCHS/SOL participants. All participants who were able and willing to attend a separate visit within 9 months of their HCHS/SOL baseline exam were eligible; of 7,321 individuals whom recruiters attempted to reach, 5,313 (N = 72.6 %) participated. Sociocultural Ancillary Study participants are largely representative of the HCHS/SOL cohort, with the exception of lower participation among some higher socioeconomic strata (Gallo, et al., 2014). Measures of functional and structural social support were administered in the sociocultural exam. Participants with missing data on social support measures (N = 126) or diabetes status (N = 6) were excluded from the current study; thus, analyses are based on N = 5,181 men and women. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from all study sites for all HCHS/SOL and HCHS/SOL Sociocultural Ancillary Study procedures and materials.

Measures

Social support

The 12-item Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL-12) (Cohen, et al., 1985) was used to assess functional (i.e., perceived) social support. Scores range from 0 to 36 with higher scores reflecting greater perceived support. Analyses with this measure in the HCHS/SOL sociocultural cohort showed evidence of internal consistency (Cronbach’s αs >.80 for both language and all Hispanic background groups), support for the one factor structure, evidence of factorial invariance across language and background groups, and construct validity in the form of theoretically consistent patterns of associations with other constructs (Merz et al., 2014). The Social Network Index (Cohen et al., 1997) was used to assess structural support. This 25-item scale provides a count (range 0–12) of the number of high contact (at least once each 2 weeks) social roles (e.g., friend, co-worker) the respondent has. Internal consistency and other psychometric data are not reported for this scale given the count format and the fact that it is not intended to capture underlying latent construct(s). However, the range of roles surveyed is generally applicable across population groups.

Diabetes prevalence

Participants who (a) self-reported receiving a diagnosis of diabetes by a doctor, and/or (b) were taking medication for glucose regulation, and/or (c) met current criteria for diabetes according to physiological markers (fasting plasma glucose ≥126 mg/dL, 2-h plasma glucose >200 mg/dl during OGTT, HbA1c ≥6.5 %) (American Diabetes Association, 2013a) were coded as having diabetes. For secondary analyses, participants who met criteria (a) or (b) were categorized as having previously diagnosed diabetes. Those who met criterion (c) [but not (a) or (b)] were classified as having newly recognized diabetes based on physiological data, consistent with current diagnostic criteria (American Diabetes Association, 2013a) and with a prior study in the HCHS/SOL cohort (Schneiderman, et al., In Press). Participants who were missing medication, physiological, or diabetes self-report data (N = 155) were excluded from these analyses.

Covariates

Sociodemographic covariates included age (in years), sex, education [<high school (HS) diploma/general education degree (GED), HS diploma/GED only, >HS diploma/GED], income (10 categories, ranging from <$10,000 to >$100,000), and Hispanic background (Mexican, Cuban, Puerto Rican, Dominican, Central American, South American, other or more than one). Language of interview (Spanish or English) and immigration status (immigrated <10 years ago, immigrated >10 years ago, born in US mainland) were used as proxy indicators of acculturation, and health insurance status (any or none) was used to represent healthcare access. Marital status was examined for descriptive purposes but was not used as a covariate since it forms part of the structural support measure. BMI was indicated by weight in kg/height in m2.

Statistical analyses

All analyses account for design effects and sample weights (LaVange, et al., 2010). Sample weights are adjusted for non-response, calibrated to the 2010 U.S. Census populations (for the target communities) according to age, sex and Hispanic background, and normalized to the HCHS/SOL cohort sample size. Descriptive statistics were calculated in IBM SPSS Statistics 19.0 (IBM, Inc., Armonk, NY) using complex survey procedures. The maximum likelihood robust (MLR) estimation procedure in MPLUS (Muthén & Muthén, 2006) was used to estimate model parameters for all remaining analyses. This procedure adjusts regression parameters and standard errors for missing data. Structural and functional support indicators were first examined as predictors in separate, unadjusted logistic regression models, and then in adjusted models that controlled for sociodemographic covariates including age, sex, immigration, language, insurance, education, income, and Hispanic background.Footnote 2 Adjusted models were repeated with structural and functional support indicators entered conjointly to determine their relative effects in relation to diabetes prevalence. Additional analyses, conducted according to the same steps, used multinomial logistic regression to examine associations of social support variables with odds of previously and newly diagnosed diabetes in separate models; no diabetes was used as the referent group in these analyses. Social support predictors were standardized (M = 0, SD = 1) prior to analysis. For ease of interpretation, the inverse of odds ratios <1.0 are reported below.

Previous research suggests that the effects of low social support may be amplified in older adults (Tomaka et al., 2006), women (Coyne et al., 2001), and immigrants or less acculturated individuals (Viruell-Fuentes & Schulz, 2009). The health protective effects of social support may also be greater among individuals with lower socioeconomic status (Gorman & Sivaganesan, 2007; Schollgen et al., 2011). Thus, sensitivity analyses that included multiplicative interaction terms were conducted to examine the consistency of the adjusted associations between social support and overall diabetes prevalence across age, sex, immigration, language, income, and education groups. An alpha level of .01 was used to reduce type 1 error risk in these analyses.

Results

The association between structural and functional support measures was positive and moderate in magnitude, r = 0.28, p < .001. As shown in Table 1, 38.12 % of the sample was male and 61.09 % was aged 45 years or older. Most participants had a household income of <$30,000 (65.84 %), immigrated to the U.S. more than 10 years ago (58.91 %), and completed their interview in Spanish (80.70 %). Diabetes prevalence was 21.35 % (95 % CI 20.23–22.46) in the sample (weighted prevalence, 16.77 %; 95 % CI 15.37–18.27). On average, participants reported having 5.59 “high-contact” social roles and had an average ISEL-12 score of 25.85.

Overall diabetes prevalence

Results of analyses testing primary study hypotheses are presented in Table 2. In adjusted models, a one SD higher structural or functional support score was related to 16 % (i.e., 1/0.86) and 15 % (i.e., 1/0.87) lower odds, respectively, of having diabetes. Tests of interaction effects showed that these associations were consistent across demographic groups (all p values >.01). When modeled simultaneously, associations of both types of social support with diabetes prevalence remained statistically significant; one SD higher structural or functional support was related to 12 and 11 % lower odds, respectively, of having diabetes (p values <.05), in the adjusted model.

Previously diagnosed and newly diagnosed diabetes

One SD higher structural or functional support was related to 19 and 14 % lower odds, respectively, of having previously diagnosed (vs. no) diabetes, and 19 and 20 % lower odds, respectively, of having newly diagnosed (vs. no) diabetes (all p values <.05) (see Table 2). When effects of both types of support were conjointly tested in adjusted models, higher structural support was associated with 16 % lower odds of previously diagnosed diabetes (p < .05), whereas functional support was not significantly related to this outcome. Neither social support variable was found to be associated with odds of having newly diagnosed diabetes in adjusted, conjoint models.

Discussion

The current study is the first, to our knowledge, to demonstrate that higher social support is related to lower odds of diabetes prevalence among Hispanics of diverse backgrounds, and is among the first to examine the association of social support with diabetes prevalence or incidence in any population. The study also adds to the very limited research that has examined psychosocial factors in relation to objectively assessed physical health outcomes in Hispanics. This is an important research emphasis, given the growth of the Hispanic population. According to the 2010 U.S. Census, Hispanics comprised 16 % of the US population and accounted for 56 % of the population growth between 2000 and 2010 (Ennis et al., 2011). In addition, protective social factors associated with the traditional Hispanic culture represent one potential explanation for the so called “Hispanic Paradox”, yet to date, very little is known the psychosocial correlates of health in the diverse U.S. Hispanic population. The HCHS/SOL provides a unique opportunity to examine the psychosocial correlates of health in a cohort that includes representation of several background groups, and a range of socioeconomic and acculturation levels (Gallo, et al., 2014).

The results showed that higher levels of structural and functional social support were associated with lower odds of diabetes prevalence. Effects were small in magnitude, but were statistically significant after adjusting for a range of sociodemographic covariates, and were consistent across demographic groups defined by age, sex, immigration, language, income, education, and Hispanic ancestry. Although prior research has identified differential health implications of functional versus structural support (Barth, et al., 2010), including a study of social support and diabetes risk (Norberg, et al., 2007), both types of support were independently related to diabetes prevalence in this cohort. Structural social support may be important because it indicates regular social contact and promotes role diversity, thus contributing to a sense of meaning in life that enhances health and well-being, and because it fosters accessible functional support (Uchino, 2004). In turn, functional support provides access to specific resources (or perceptions that they are available if needed), which can attenuate stress appraisals and enhance positive coping with stressors ranging in severity from minor daily hassles to major life events (Uchino, 2004). Ultimately, direct and indirect behavioral and physiological pathways are believed to underlie the associations of functional and structural social support with physical health outcomes, as detailed above.

Analyses separately examining associations of functional and structural social support with previously diagnosed and newly recognized diabetes cases provide additional information. Specifically, the associations of structural support with previously diagnosed and newly recognized diabetes (vs. no diabetes) were equivalent in strength. Associations of functional support with each outcome were also similar in magnitude, though the association with previously diagnosed diabetes was slightly stronger. In analyses that simultaneously modeled effects of functional and structural support in relation to newly or previously diagnosed versus no diabetes, only the association of structural support with previously diagnosed diabetes remained statistically significant. This may in part reflect the shared influences of these constructs as discussed above, but could also reflect the lower statistical power inherent to these conjoint analyses. Although the cross-sectional design precludes conclusions regarding causality or directionality, the relationship of social support to the prevalence of diabetes that was newly recognized at the baseline exam provides indirect, albeit preliminary evidence for an etiological role of social support in the diabetes pathophysiological process. For example, it is possible that individuals with diabetes may withdraw from certain social roles (e.g., employee, volunteer) due to illness or disability, or, their friends and family may become less willing to provide support and assistance over time, as support sources become taxed or exhausted. Indeed, there is evidence that stressful circumstances, such as those associated with a health crisis, can erode social support (Bolger et al. 1996; Uchino 2009). It is probable that individuals who were unaware of their diabetes diagnosis prior to the HCHS/SOL baseline exam had less advanced disease, relative to those who had sought care. In addition, individuals who were not aware they had diabetes would be less likely to rely on their support networks for assistance in coping with their health and medical care, at least as related to diabetes specifically. The fact that effects of support emerged in relation to newly recognized diabetes provides the impetus for future research that explores the etiological role of social support in diabetes.

In addition to the cross-sectional design, several limitations of the current study should be noted. The social support and diabetes variables were ascertained at different points in time. The Sociocultural Ancillary Study was initiated during the second wave of HCHS/SOL recruitment, and a generous window (9 months) was adopted between the baseline and sociocultural exam to ensure a more inclusive approach. Notably, 88.3 % of participants completed the sociocultural assessment within 6 months and 72.6 % within 4 months of their baseline exam (Gallo, et al., 2014). The clinical exam with OGTT, HbA1c, and fasting glucose represents a rigorous approach for detecting diabetes in a large cohort study such as the HCHS/SOL. However, a small number of cases were based on self-reported information alone (for prevalence analyses only) and this may have introduced error into the categorization scheme. In addition, we were unable to distinguish between type 1 and type 2 diabetes. However, only 2.6 % of participants aged 18–29 in the HCHS/SOL cohort had diabetes (Schneiderman, et al., In Press) and at the population level, 90–95 % of diabetes cases are type 2 rather than type 1 (American Diabetes Association, 2013a). Thus it is unlikely that this imprecision significantly affected our results.

Limitations not withstanding, the current findings add to the limited evidence suggesting that social support may relate to the occurrence of diabetes. In addition, they build upon the small body of research suggesting the protective health implications of social support in US Hispanics (Bell, et al., 2010; Fortmann, et al., 2011), in a large cohort representing multiple backgrounds, varied levels of socioeconomic status and acculturation, and several geographic locations with large metropolitan Hispanic populations. Given the marked increases in diabetes rates among Hispanics (Cowie, et al., 2009; Schneiderman et al., 2014), and the tremendous economic burden this condition exacts (e.g., total costs of $245 billion in 2012 American Diabetes Association, 2013b), it is important to identify modifiable risk and protective factors to inform prevention efforts in this population. Health promotion or disease management interventions with a social support emphasis have varied widely and many studies of their effectiveness have important methodological limitations, or have produced mixed findings (Hogan et al., 2002). Nonetheless, a systematic review of support interventions tested across emotional and physical health contexts found that 73/92 (83 %) randomized controlled trials identified at least some benefits of support promoting interventions (Hogan et al., 2002), suggesting that efforts to modify support may be a useful strategy. In addition, specific social support enhancing intervention approaches (social support groups, group medical visits) appear to be effective in promoting better self-management and clinical outcomes in patients with diabetes (van Dam et al., 2005), and could also be useful in a prevention context. To justify such efforts, further research based on the HCHS/SOL and other cohorts is needed to examine the association of social support with diabetes incidence and to elucidate the specific direct and indirect mechanisms that underlie this association.

Notes

We use “Hispanic” to encompass the terms Hispanic, Latino, and others that may be favored by certain ethnic or geographic groups, acknowledging that there are differences of opinion regarding the meaning and relevance of these terms.

Additional control for BMI did not substantively alter results. In addition, BMI is viewed as a pathway through which support could relate to diabetes, rather than a confounding factor; thus, BMI was excluded from models.

References

Adam, T. C., & Epel, E. S. (2007). Stress, eating and the reward system. Physiology & Behavior, 91, 449–458. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.04.011

American Diabetes Association. (2013a). Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care, 36, S67–S74. doi:10.2337/dc13-S067

American Diabetes Association. (2013b). Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2012. Diabetes Care, 36, 1033–1046. doi:10.2337/dc12-2625

Arias, E., Eschbach, K., Schauman, W. S., Backlund, E. L., & Sorlie, P. D. (2010). The Hispanic mortality advantage and ethnic misclassification on US death certificates. American Journal of Public Health, 100, S171–S177. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2008.135863

Ayala, G. X., Carnethon, M., Arredondo, E., Delamater, A. M., Perreira, K., Van Horn, L., et al. (2014). Theoretical foundations of the Study of Latino (SOL) Youth: Implications for obesity and cardiometabolic risk. Annals of Epidemiology, 24, 36–43. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.10.011

Barth, J., Schneider, S., & Von Känel, R. (2010). Lack of social support in the etiology and the prognosis of coronary heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychosomatic Medicine, 72, 229–238.

Beaudry, J. L., & Riddell, M. C. (2012). Effects of glucocorticoids and exercise on pancreatic β-cell function and diabetes development. Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews, 28, 560–573. doi:10.1002/dmrr.2310

Bell, C. N., Thorpe, R. J., Jr, & Laveist, T. A. (2010). Race/ethnicity and hypertension: The role of social support. American Journal of Hypertension, 23, 534–540. doi:10.1038/ajh.2010.28

Black, P. H. (2006). The inflammatory consequences of psychologic stress: Relationship to insulin resistance, obesity, atherosclerosis and diabetes mellitus, type II. Medical Hypotheses, 67, 879–891.

Bolger, N., Foster, M., Vinokur, A. D., & Ng, R. (1996). Close relationships and adjustments to a life crisis: The case of breast cancer. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 283–294.

Brissette, I., Cohen, S., & Seeman, T. E. (2000). Measuring social integration and social networks. In S. Cohen, L. G. Underwood, & B. H. Gottlieb (Eds.), Social support measurement and intervention: A guide for health and social scientists (pp. 53–85). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Buren, J., & Eriksson, J. W. (2005). Is insulin resistance caused by defects in insulin’s target cells or by a stressed mind? Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews, 21, 487–494. doi:10.1002/dmrr.567

Buttenheim, A. M., Pebley, A. R., Hsih, K., Chung, C. Y., & Goldman, N. (2013). The shape of things to come? Obesity prevalence among foreign-born vs. US-born Mexican youth in California. Social Science and Medicine, 78, 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.10.023

Campbell, J., Walker, R., Smalls, B., & Egede, L. (2012). Glucose control in diabetes: The impact of racial differences on monitoring and outcomes. Endocrine, 42, 471–482. doi:10.1007/s12020-012-9744-6

Caplan, S. (2007). Latinos, acculturation, and acculturative stress: A dimensional concept analysis. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice, 8, 93–106. doi:10.1177/1527154407301751

Cohen, S., Doyle, W. J., Skoner, D. P., Rabin, B. S., & Gwaltney, J. M., Jr. (1997). Social ties and susceptibility to the common cold. JAMA, 277, 1940–1944. doi:10.1001/jama.1997.03540480040036

Cohen, S., Mermelstein, R., Kamarck, T., & Hoberman, H. M. (1985). Measuring the functional components of social support. In I. G. Sarason & B. R. Sarason (Eds.), Social support: Theory, research, and applications (pp. 73–94). The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-5115-0_5

Cortes-Bergoderi, M., Goel, K., Murad, M. H., Allison, T., Somers, V. K., Erwin, P. J., et al. (2013). Cardiovascular mortality in Hispanics compared to non-Hispanic whites: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the Hispanic paradox. European Journal of Internal Medicine, 24, 791–799. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2013.09.003

Cosgrove, M. P., Sargeant, L. A., Caleyachetty, R., & Griffin, S. J. (2012). Work-related stress and Type 2 diabetes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Occupational Medicine, 62, 167–173.

Cowie, C. C., Rust, K. F., Ford, E. S., Eberhardt, M. S., Byrd-Holt, D. D., Li, C., et al. (2009). Full accounting of diabetes and pre-diabetes in the U.S. population in 1988–1994 and 2005–2006. Diabetes Care, 32, 287–294.

Coyne, J. C., Rohrbaugh, M. J., Shoham, V., Sonnega, J. S., Nicklas, J. M., & Cranford, J. A. (2001). Prognostic importance of marital quality for survival of congestive heart failure. American Journal of Cardiology, 88, 526–529.

Daviglus, M. L., Talavera, G. A., Aviles-Santa, M. L., Allison, M., Cai, J., Criqui, M. H., et al. (2012). Prevalence of major cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular diseases among Hispanic/Latino individuals of diverse backgrounds in the United States. JAMA, 308, 1775–1784. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.14517

Elder, J. P., Ayala, G. X., Parra-Medina, D., & Talavera, G. A. (2009). Health communication in the Latino community: Issues and approaches. Annual Revivew of Public Health, 30, 227–251. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100300

Ennis, S. R., Rios-Vargas, M., & Albert, N. (2011). The Hispanic population: 2010 Census Briefs. US Census Bureau. http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-04.pdf

Fortmann, A. L., & Gallo, L. C. (2013). Social support and nocturnal blood pressure dipping: A systematic review. American Journal of Hypertension, 26, 302–310. doi:10.1093/ajh/hps041f

Fortmann, A. L., Gallo, L. C., & Philis-Tsimikas, A. (2011). Glycemic control among Latinos with type 2 diabetes: The role of social-environmental support resources. Health Psychology, 30, 251–258. doi:10.1037/a0022850

Gallant, M. P. (2003). The influence of social support on chronic illness self-management: A review and directions for research. Health Education & Behavior, 30, 170–195. doi:10.1177/1090198102251030

Gallo, L. C., Penedo, F. J., Carnethon, M., Isasi, C., Sotrez-Alvarez, D., Malcarne, V. L., et al. (2014). The Hispanic community health study/study of Latinos sociocultural ancillary study: Sample, design, and procedures. Ethnicity and Disease, 24, 77–83.

Gallo, L. C., Penedo, F. J., Espinosa De Los Monteros, K., & Arguelles, W. (2009). Resiliency in the face of disadvantage: Do Hispanic cultural characteristics protect health outcomes? Journal of Personality, 77, 1707–1746. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00598.x

Go, A. S., Mozaffarian, D., Roger, V. L., Benjamin, E. J., Berry, J. D., Blaha, M. J., et al. (2013). Heart disease and stroke statistics—2014 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation,. doi:10.1161/01.cir.0000441139.02102.80

Gorman, B. K., & Sivaganesan, A. (2007). The role of social support and integration for understanding socioeconomic disparities in self-rated health and hypertension. Social Science and Medicine, 65, 958–975. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.04.017

Harris, M. I. (2001). Racial and ethnic differences in health care access and health outcomes for adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care, 24, 454–459. doi:10.2337/diacare.24.3.454

Hogan, B. E., Linden, W., & Najarian, B. (2002). Social support interventions: Do they work? Clinical Psychology Review, 22, 383–442. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(01)00102-7

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., & Layton, J. B. (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Medicine, 7, e1000316. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316

Isasi, C. R., Carnethon, M. R., Ayala, G. X., Arredondo, E., Bangdiwala, S. I., Daviglus, M. L., et al. (2014). The Hispanic Community Children’s Health Study/Study of Latino Youth (SOL Youth): Design, objectives, and procedures. Annals of Epidemiology, 24, 29–35. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.08.008

Jasso, G., Massey, D. S., Rosenzweig, M. R., & Smith, J. P. (2004). Immigrant health-selectivity and acculturation. In N. B. Anderson, R. A. Bulatao, & B. Cohen (Eds.), Critical perspectives on racial and ethnic differences in health in late life (pp. 227–266). Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Kershaw, E. F., & Flier, J. S. (2004). Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 89, 2548–2556. doi:10.1210/jc.2004-0395

Kumari, M., Head, J., & Marmot, M. (2004). Prospective study of social and other risk factors for incidence of type 2 diabetes in the Whitehall II study. Archives of Internal Medicine, 164, 1873–1880. doi:10.1001/archinte.164.17.1873

Kurian, A. K., & Cardarelli, K. M. (2007). Racial and ethnic differences in cardiovascular disease risk factors: A systematic review. Ethnicity and Disease, 17, 143–152.

Kyrou, I., & Tsigos, C. (2009). Stress hormones: Physiological stress and regulation of metabolism. Current Opinion in Pharmacology, 9, 787–793. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2009.08.007

Lakey, B., & Cohen, S. (2000). Social support theory and measurement. In S. Cohen, L. G. Underwood & B. H. Gottlieb (Eds.), Social support measurement and intervention: A guide for health and social scientists (pp. 29–52). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lanting, L. C., Joung, I. M., Mackenbach, J. P., Lamberts, S. W., & Bootsma, A. H. (2005). Ethnic differences in mortality, end-stage complications, and quality of care among diabetic patients: A review. Diabetes Care, 28, 2280–2288. doi:10.2337/diacare.28.9.2280

Lavange, L. M., Kalsbeek, W. D., Sorlie, P. D., Avilès-Santa, L. M., Kaplan, R. C., Barnhart, J., et al. (2010). Sample design and cohort selection in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Annals of Epidemiology, 20, 642–649. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.05.006

Markides, K. S., & Eschbach, K. (2011). Hispanic paradox in adult mortality in the United States. In R. G. Rogers & E. M. Crimmins (Eds.), International handbook of adult mortality (Vol. 2, pp. 227–240). Berlin: Springer.

Mcewen, B. S. (2012). Brain on stress: How the social environment gets under the skin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, 109, 17180–17185. doi:10.1073/pnas.1121254109

Merz, E. L., Roesch, S. C., Malcarne, V. L., Penedo, F. J., Llabre, M. M., Weitzman, O. B., et al. (2014). Validation of Interpersonal Support Evaluation List-12 (ISEL-12) scores among English- and Spanish-speaking Hispanics/Latinos from the HCHS/SOL Sociocultural Ancillary Study. Psychological Assessment, 26, 384–394. doi:10.1037/a0035248

Mookadam, F., & Arthur, H. M. (2004). Social support and its relationship to morbidity and mortality after acute myocardial infarction: Systematic overview. Archives of Internal Medicine, 164, 1514–1518. doi:10.1001/archinte.164.14.1514

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2006). Mplus. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén.

Norberg, M., Stenlund, H., Lindahl, B., Andersson, C., Eriksson, J. W., & Weinehall, L. (2007). Work stress and low emotional support is associated with increased risk of future type 2 diabetes in women. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 76, 368–377. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2006.09.002

Olefsky, J. M., & Glass, C. K. (2010). Macrophages, inflammation, and insulin resistance. Annual Review of Physiology, 72, 219–246. doi:10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135846

Peckett, A. J., Wright, D. C., & Riddell, M. C. (2011). The effects of glucocorticoids on adipose tissue lipid metabolism. Metabolism, 60, 1500–1510. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2011.06.012

Perez, G. K., & Cruess, D. (2011). The impact of familism on physical and mental health among Hispanics in the United States. Health Psychology Review, 1–33. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2011.569936

Pescosolido, B. A., & Levy, J. A. (2002). The role of social networks in health, illness, disease and healing: The accepting present, the forgotten past, and the dangerous potential for a complacent future. In J. A. Levy & B. A. Pescosolido (Eds.), Social networks and health (Advances in Medical Sociology) (Vol. 8, pp. 3–25). United Kingdom: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Pew Hispanic Center. (2011). Census 2010: 50 Million Latinos. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center.

Pew Hispanic Center. (2014). Statistical portrait of Hispanics in the United States, 2012. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center.

Pinquart, M., & Duberstein, P. R. (2010). Associations of social networks with cancer mortality: A meta-analysis. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology, 75, 122–137. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2009.06.003

Ruiz, J. M., Steffen, P., & Smith, T. B. (2013). Hispanic mortality paradox: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the longitudinal literature. American Journal of Public Health, 103, e52–e60. doi:10.2105/ajph.2012.301103

Schneiderman, N., Llabre, M., Cowie, C., Barnhart, J., Carnethon, M., Gallo, L. C., et al. (2014). Prevalence of diabetes among Hispanics/Latinos from Diverse Backgrounds: The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL). Diabetes Care, 37, 2233–2239. doi:10.2337/dc13-2939

Schollgen, I., Huxhold, O., Schuz, B., & Tesch-Romer, C. (2011). Resources for health: Differential effects of optimistic self-beliefs and social support according to socioeconomic status. Health Psychology, 30, 326–335. doi:10.1037/a0022514

Singh, G. K., Rodriguez-Lainz, A., & Kogan, M. D. (2013). Immigrant health inequalities in the United States: Use of eight major national data systems. Scientific World Journal, 2013, 512313. doi:10.1155/2013/512313

Smith, S. M., & Vale, W. W. (2006). The role of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in neuroendocrine responses to stress. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 8, 383–395.

Sorlie, P. D., Avilès-Santa, L. M., Wassertheil-Smoller, S., Kaplan, R. C., Daviglus, M. L., Giachello, A. L., et al. (2010). Design and Implementation of the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Annals of Epidemiology, 20, 629–641. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.03.015

Stopford, R., Winkley, K., & Ismail, K. (2013). Social support and glycemic control in type 2 diabetes: A systematic review of observational studies. Patient Education and Counseling, 93, 549–558. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2013.08.016

Teruya, S. A., & Bazargan-Hejazi, S. (2013). The immigrant and Hispanic paradoxes: A systematic review of their predictions and effects. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 35, 486–509. doi:10.1177/0739986313499004

Thoits, P. A. (2011). Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 52, 145–161. doi:10.1177/0022146510395592

Tomaka, J., Thompson, S., & Palacios, R. (2006). The relation of social isolation, loneliness, and social support to disease outcomes among the elderly. Journal of Aging and Health, 18, 359–384. doi:10.1177/0898264305280993

Tsatsoulis, A., Mantzaris, M. D., Bellou, S., & Andrikoula, M. (2013). Insulin resistance: An adaptive mechanism becomes maladaptive in the current environment—an evolutionary perspective. Metabolism, 62, 622–633. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2012.11.004

Uchino, B. N. (2004). Social support and physical health: Understanding the health consequences of our relationships. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Uchino, B. N. (2006). Social support and health: A review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 29, 377–387. doi:10.1007/s10865-006-9056-5

Uchino, B. N. (2009). Understanding the links between social support and physical health: A life-span perspective with emphasis on the separability of perceived and received support. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4, 236–255. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01122.x

Uchino, B. N. (2013). Understanding the links between social ties and health: On building stronger bridges with relationship science. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 30, 155–162. doi:10.1177/0265407512458659

Uchino, B. N., Bowen, K., Carlisle, M., & Birmingham, W. (2012). Psychological pathways linking social support to health outcomes: A visit with the “ghosts” of research past, present, and future. Social Science and Medicine, 74, 949–957. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.023

Umberson, D., Crosnoe, R., & Reczek, C. (2010). Social relationships and health behavior across the life course. Annual Review of Sociology, 36, 139–157. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-120011

Van Dam, H. A., Van Der Horst, F. G., Knoops, L., Ryckman, R. M., Crebolder, H. F. J. M., & Van Den Borne, B. H. W. (2005). Social support in diabetes: A systematic review of controlled intervention studies. Patient Education and Counseling, 59, 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2004.11.001

Viruell-Fuentes, E. A., & Schulz, A. J. (2009). Toward a dynamic conceptualization of social ties and context: Implications for understanding immigrant and Latino health. American Journal of Public Health, 99, 2167–2175. doi:10.2105/ajph.2008.158956

Acknowledgments

The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos was carried out as a collaborative study supported by contracts from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) to the University of North Carolina (N01-HC65233), University of Miami (N01-HC65234), Albert Einstein College of Medicine (N01-HC65235), Northwestern University (N01-HC65236), and San Diego State University (N01-HC65237). The following Institutes/Centers/Offices contribute to the HCHS/SOL through a transfer of funds to the NHLBI: National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Office of Dietary Supplements. The HCHS/SOL Sociocultural Ancillary Study was supported by Grant 1 RC2 HL101649 from the NIH/NHLBI (Gallo/Penedo PIs). The authors thank the staff and participants of HCHS/SOL and the HCHS/SOL Sociocultural Ancillary Study for their important contributions.

Conflict of Interest

Authors Gallo, Fortmann, McCurley, Isasi, Penedo, Daviglus, Roesch, Talavera, Gouskova, Gonzalez, Schneiderman, and Carnethon declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gallo, L.C., Fortmann, A.L., McCurley, J.L. et al. Associations of structural and functional social support with diabetes prevalence in U.S. Hispanics/Latinos: Results from the HCHS/SOL Sociocultural Ancillary Study. J Behav Med 38, 160–170 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-014-9588-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-014-9588-z